Abstract

Objective

We report a gene x environment (health) study focusing on concurrent performance and longitudinal change in a latent-variable executive function (EF) phenotype. Specifically, we tested the independent and interactive effects of a recently identified insulin degrading enzyme genetic polymorphism (IDE rs6583817) and pulse pressure (PP) (one prominent aging-related vascular health indicator) across up to 9 years of EF data in a sample of older adults from the Victoria Longitudinal Study. Both factors vary across a continuum of risk-elevating to risk-reducing and have been recently linked to normal and impaired cognitive aging.

Method

We assembled a genotyped and typically aging group of older adults (n=599, M age=66 years at baseline), following them for up to three longitudinal waves (M interval=4.4 years). We used confirmatory factor analyses, latent growth modeling, and path analyses to pursue three main research goals.

Results

First, the EF single factor model was confirmed as comprised of 4 executive function tasks and it demonstrated measurement invariance across the waves. Second, older adults with the major IDE G allele exhibited better EF outcomes than homozygotes for the minor A allele at the centering age of 75 years. Adults with higher PP performed more poorly on EF tasks at age 75 years and exhibited greater EF longitudinal decline. Third, gene x health interaction analyses showed that worsening vascular health (higher PP) differentially affected EF performance in older adults with the IDE G allele.

Discussion

Genetic interaction analyses can reveal differential and magnifying effects on cognitive phenotypes in aging. In the present case, pulse pressure is confirmed as a risk factor for concurrent and changing cognitive health in aging, but the effects operate differently across the risk and protective allelic distribution of this IDE gene.

Keywords: Executive functions, gene x health analyses, insulin degrading enzyme, pulse pressure, Victoria Longitudinal Study

Cognitive deficits increase with age but the dynamics of when, how, and why the decrements accumulate are among the key questions of cognitive aging research (Dixon, Small, MacDonald, & McArdle, 2012; Hertzog, 2008). The timing, trajectories, and etiologies of aging-related cognitive decrements vary between people, across cognitive domains, and seem to occur later and more differentially than once thought (e.g., Schaie, 2013; Small, Dixon, & McArdle, 2011). Although both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies offer much insight into patterns of normal cognitive aging, studies with both biological markers (biomarkers) and multiple waves of observation are especially well-equipped to address these issues. Both modifiable (lifestyle, health related) and non-modifiable (genetic) factors may influence differences in cognitive performance and changes, with the influences potentially operating both independently and interactively (Dahl, Jacobs, & Raz, 2009; Dixon, 2011; Fotuhi, Hachinski, & Whitehouse, 2009; Harris & Deary, 2011; Lindenberger et al., 2008; Nagel et al., 2008; Small, Dixon, McArdle, & Grimm, 2012; Song, Mitnitski, & Rockwood, 2011; Waldstein et al., 2008). Whereas the independent influences of these factors on concurrent cognitive health are important to identify and describe, further progress may accrue by examining the role of gene x environment (health) interactions with both concurrent and longitudinal data.

One cognitive domain that is influenced by several of the aforementioned factors is executive function (Luszcz, 2011). Briefly, executive functions (EF) are cognitive processes required in order to execute plans, solve problems, and partake in goal directed endeavors (West, 1996). EFs are known to decline with advancing age and are thought to have direct links to neurodegeneration of the prefrontal cortex (Luszcz, 2011; Turner & Spreng, 2012). Clinically, performance on some EF tests is predictive of future development of mild cognitive impairment (Nathan, Wilkinson, Stammers, & Low, 2001) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD; Grober et al., 2008, Rapp & Reischies, 2005). Conceptually, EF is made up of functions primarily reflecting aspects of inhibition, shifting, and updating. The developmental trajectory of EF is evidenced by apparent shifts in structure and level across the lifespan (de Frias, Dixon, & Strauss, 2006; Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, & Howerter, 2000; Wiebe, Espy, Charak, 2008; Wiebe et al., 2010). Although generally unidimensional within older adults, differences in EF structure (and level) have been observed across groups of healthy (e.g., cognitively elite) aging, normal aging, and mild cognitive impairment (de Frias, Dixon, & Strauss, 2009). Increasingly, research has shown that EF performance patterns are affected or modified by a host of biological, neurobiological, health, and environmental factors (de Frias et al., 2006; Grober et al., 2008; Lindenberger et al., 2008; Luszcz, 2011; McFall et al., 2013; Nathan et al., 2001; Rapp & Reischies, 2005; Wishart et al., 2011; Yeung, Fischer, & Dixon, 2009).

In this study we address the aging of EF as it is related to specific health (PP an indicator of vascular health) and biological (genetic) factors (Luszcz, 2011; Turner & Spreng, 2012). Regarding health, research shows that overall vascular health declines with age and may be a direct contributor to cognitive (including EF) deficits and even dementia (Qiu, Winblad, & Fratiglioni, 2005; Raz, Rodrigue, & Acher, 2003; Vasan et al., 2001). More specifically, increases in blood pressure, related to declining vascular health, have been associated with reduced brain tissue volume, especially prefrontal structures and, not surprisingly, decreases in EF performance (Dahle, Jacobs, & Raz, 2009; Elias, Elias, Robbins, & Budge, 2004; Raz et al., 2003; Waldstein et al., 2008). Notably, some aspects of vascular health may be modifiable and indeed maintenance of good vascular health in older adulthood may be correspondingly protective of cognitive functioning as evidenced by preserved brain tissue (Colcombe et al., 2003) and the possible postponement of dementia onset (Qiu et al., 2005; Staessen, Richart, & Bikenhäger, 2007).

Numerous aspects and indicators of vascular health may be studied in research on cognitive aging. As noted, we focus on PP which is conceptually linked to arterial stiffening. This vascular change increases with age and is associated with increases in systolic blood pressure and decreases in diastolic blood pressure (Franklin et al., 1997; Mattace-Raso et al., 2006, Raz, Dahle, Rodrigue, Kennedy, & Land, 2011). In addition, arterial stiffening has been found to have an independent effect on cardiovascular disease (Dart & Kingwell, 2001; Mitchell et al., 2007; Schiffrin, 2004) and cognitive performance in older non-demented adults (Dahl et al., 2009; McFall et al., 2013; Waldstein et al., 2008). Arterial stiffness may be measured by directly by pulse wave velocity, but PP is considered a proxy (Waldstein et al., 2008). PP is calculated as systolic minus diastolic blood pressure. Typically, it shows a steep age-related increase in older adults and is considered a better predictor of declining vascular health than systolic blood pressure (Raz et al., 2011). Several researchers have reported PP associations with EF deficits (Dahle et al., 2009; Raz et al., 2011, Waldstein et al, 2008) and an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia (Qui, Winblad, Viitanen, & Fratiglioni, 2003).

Whereas PP is a prominent and modifiable health factor influencing cognition aging, genetic influences are relatively time-invariant and non-modifiable influences. Researchers have recently explored associations of selected genetic polymorphisms not only to cognitive impairment and dementia (e.g., Apolipoprotein E (ApoE ɛ4); Brainerd, Reyna, Petersen, Smith, & Taub, 2011) but also to normal cognitive differences and decline (Deary, Wright, Harris, Whalley, & Starr, 2004; Harris & Deary, 2011; Kremen & Lyons, 2011). Of recent and growing interest is the insulin degrading enzyme gene (IDE), for which variants have been linked to increased risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D), dementia, and AD (Bartl et al., 2011, Belbin et al., 2011; Carrasquillo et al., 2010). While IDE is most commonly recognized for its role in the degradation of insulin, this enzyme has also been linked to the processing of the glycemia-regulating peptides amylin and glucagon (Bennett, Duckworth, & Hamel, 2000; Shen, Joachimiak, Rosner, & Tang, 2006) and the human amyloid precursor protein (amyloid beta, Aβ; Kurochkin & Goto, 1994). Neurogenetic research has identified an IDE linkage peak for such major aging-related diseases as T2D and late onset AD. Several IDE haplotypes have been identified and individual SNPs have been associated with either an increased or decreased risk of developing T2D or AD (Bartl et al., 2011). The IDE alleles associated with T2D risk may be due to the lowered expression of IDE, which may result in hyperinsulinemia and consequent cognitive deficits (Awad, Gagnon, & Messier, 2004; Umegaki, 2012). Alternatively, IDE SNPs associated with decreased risk of AD may be due to higher IDE expression and Aβ level decreases (Qiu & Folstein, 2006; Blomqvist et al., 2005; Kurochkin & Goto, 1994). Three genetic variants of IDE (rs6583817, rs5786996; rs4646953) have been identified as having the strong association with increased levels of IDE expression and decreased Aβ levels (Belbin et al., 2011; Carrasquillo et al., 2010). In our research, we have focused on one of these especially promising IDE (rs6583817) SNPs, which has a minor A allele and a major G allele. To our knowledge, the first gene association study with this variant observed increased IDE expression and decreased Aβ levels (Belbin et al., 2011; Carrasquillo et al., 2010). In a recent study we observed a positive effect of the major G allele on EF performance (McFall et al., 2013). Specifically, normal older adults possessing one or more major (G) alleles had higher levels of EF at age 75 years and less change over a four-year period than adults with the minor allele (A). Our findings supported the hypothesized mechanism that the IDE G allele was associated with decreased levels of insulin degrading enzyme, and that this translated to more insulin in the prefrontal cortex and better EF performance (for a review of the molecular mechanism relating IDE with EF function in older adults see Bartl et al., 2011; Belbin et al., 2011; Carrasquillo et al, 2010; McFall et al., 2013). The link between increases in brain insulin to improvements in EF performance has been documented (Awad et al., 2004; for basic insulin-brain-cognition reviews see Biessels, Deary, & Ryan, 2008; Craft & Watson, 2004; Seaquist, Latteman, & Dixon, 2012). In the previous study, McFall and colleagues (2013) found that IDE did not predict risk of T2D diagnosis, but whether it is associated with a more basic vascular health marker—and through vascular health to cognition in aging—is as yet unknown but plausible. Other genetic variants associated with cognitive aging have been linked to vascular health (e.g., ApoE, COMT, and ACE; Anstey & Christensen, 2000; Haan, Shemanski, Jagust, Manolio, & Kuller, 1999; Hagen et al., 2007; Mahley & Rall, 2000; Raz et al., 2011; Smith, 2002; Stern□ng et al., 2009), with growing interest in examining both independent and interaction associations (Lindenberger et al., 2008; Raz, Rodrigue, Kennedy, & Land, 2009) leading to magnifying or mitigating effects on cognitive phenotypes.

The overarching goal of the current study is to examine the independent and interactive effects of PP and IDE (rs6583817) genotype on executive function (EF) performance and longitudinal change in a group of typically aging older adults. We used a relatively large sample of older adults (n = 599) with IDE genotype information to explore four research goals. Using confirmatory factor analysis within a structural equation modeling context we examined the first two research questions. Research goal 1 was to estimate an EF latent variable using four measures related to two EF domains and to test this model for longitudinal measurement invariance across three waves. Research goal 2 was to determine the best fitting latent growth models for EF and for PP. Using conditional growth models we explored two additional research goals. Research goal 3 was to determine how EF performance patterns of change in older adults (aged 53–95 years) were affected independently by PP and IDE (rs6583817). Research goal 4 was to determine if any IDE allele-EF relationship was modified by PP.

Methods

Participants

Participants were community-dwelling adults (initially aged 55–85 years) drawn from the Victoria Longitudinal Study (VLS). The VLS is a longitudinal sequential study designed to examine older adult development in relation to biomedical, genetic, health, cognitive and neuropsychological aspects (see Dixon & de Frias, 2004). The VLS and all present data collection procedures were in full and certified compliance with prevailing human research ethics guidelines and boards. Informed written consent was provided by all participants. Using standard procedures (e.g., Dixon et al., 2012; Small et al., 2011), we assembled longitudinal data consisting of three samples and all available waves (up to three) since the early 2000s. The executive function tasks required for this study were installed in the VLS neuropsychological battery at this point. Therefore, the first included wave for each sample was the first exposure to the executive function tasks (i.e., S1W6; S2W4; S3W1). This study assembled (a) Sample 1 (S1) Waves 6 and 7, (b) Sample 2 (S2) Waves 4 and 5, and (c) Sample 3 (S3) Waves 1, 2, and 3. The mean intervals between the waves of data collection were 4.44 (W1-W2) and 4.46 (W2-W3) years. For terminological efficiency, the respective earliest wave of each sample became Wave 1 (W1 or baseline) for the current study, the respective second wave became Wave 2 (W2), and the respective third wave became Wave 3 (W3). The design stipulated that whereas S3 participants could contribute data to all three waves, S1 and S2 participants contributed data to W1 and W2 (the third wave not available). Accordingly, the present W3 sample has a relatively larger representation of participants in their 60s and 70s and a relatively smaller representation of those in their 80s and 90s. This consideration is balanced by the advantage of testing genetic-health in EF across an accelerated longitudinal period of nearly 9 years (M = 8.9 years). Demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics Categorized by Time Point

| W1 | W2 | W3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 597 | 490 | 278 |

| Gender (% Women) | 66.0 | 65.5 | 66.9 |

| Age | 70.6 (8.62) | 74.7 (8.51) | 74.9 (7.17) |

| Range | 53.2–95.2 | 57.3–94.5 | 62.4–94.9 |

| Years between waves | 4.44 (.54) | 4.46 (.71) | |

| Education | 15.3 (2.97) | 15.4 (3.01) | 15.4 (3.17) |

| Health to perfecta | 1.79 (.715) | 1.84(.719) | 1.85 (.796) |

| Health to peersb | 1.58 (.692) | 1.63 (.648) | 1.66 (.732) |

| Pulse Pressure (mmHg) | 52.2 (11.5) | 55.6 (12.9) | 55.3 (12.4) |

| Range | 32.8 – 171.4 | 26.2 – 120.9 | 29.0 – 95.5 |

| Correlation with age | .444 | .418 | .378 |

| Smoking Status (%) | n = 514 | n = 418 | n = 277 |

| Present | 3.7 | 2.6 | 1.1 |

| Previous | 51.4 | 53.8 | 53.8 |

| Never | 44.9 | 43.5 | 44.8 |

| Alcohol Use (%) | n = 514 | n = 418 | n = 277 |

| Presently | 88.3 | 89.2 | 89.5 |

| Previous | 3.9 | 8.1 | 9.0 |

| Never | 7.8 | 2.6 | 1.4 |

Note. Results presented as Mean (Standard Deviation) unless otherwise stated. Age and education presented in years. Smoking and drinking status are reported in percentages of participants who responded to the question.

Self-reported health relative to perfect.

Self-reported health relative to peers. Self-report measures are based on 1 “very good” to 5 “very poor”.

Given the necessity for both genetic and longitudinal data in this study, these factors defined the initial opportunity in sample recruitment. VLS genotyping occurred in the 2009–2011 period and was limited by funding arrangement to about 700 continuing VLS participants. After initial evaluations, the eligible source sample consisted of 683 participants with genetic data. Several exclusionary criteria were then applied to this source sample: (a) a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or any other dementia, (b) a Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) score of less than 24, (c) a self-report of “severe” for potential comorbid conditions (e.g., epilepsy, head injury, depression), (d) a self-report of “severe” or “moderate” for potential comorbid diseases such as neurological conditions (e.g., stroke, Parkinson’s disease), and (e) insufficient EF data. The final sample for this study consisted of n=598 adults. For W1 there were 597 adults, including 394 women and 203 men (M age = 70.6 years, SD = 8.61, range 53.2 – 95.2). For W2 there were 490 adults, including 321 women and 169 men (M age = 74.7 years, SD = 8.51, range 57.3 – 94.5). For W3 there were 278 adults, including 186 women and 92 men (M age = 74.9 years, SD = 7.17, range 62.4 – 94.9). In this accelerated longitudinal design, a total of 262 adults contributed data to all three waves, 272 to W1 and W2, 16 to W1 and W3, 93 to W1 only, and 1 to W2 only. The retention rates for each available and defined interval are as follows (a) S1 W1-W2 = 84%; (b) S2 W1-W2 = 77%; (c) S3 W1-W2 = 84%, (d) S3 W2-W3 = 89%, and (e) S2 W1-W3 = 77%. As noted, defined intervals are determined by availability, which in this instance is limited only by data collected and processed in this ongoing longitudinal study. For these analyses listwise deletion was not used; instead, all missing data were estimated by multiple imputations using Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Specifically, for this study 50 imputations of the data set were generated and pooled for further analyses (for further description of imputations and pooling see Enders, 2011; Graham, Olchowski, Gilreath, 2007, Muthén & Muthén, 2010; Rubin, 1987).

Executive Function Measures

All EF tests have been used widely and frequently within the VLS, with established measurement and structural characteristics (e.g., Bielak, Mansueti, Strauss, & Dixon, 2006; de Frias et al., 2006, 2009) and demonstrated sensitivity to health, genetic, and neurocognitive factors (e.g., McFall et al., 2013; Yeung et al., 2009) in various older adult populations.

Hayling sentence completion test

This task, which indexed inhibition (Bielak et al., 2006; Burgess & Shallice, 1997), consisted of two sets of 15 sentences, each having the last word missing. Section A required completing the sentence quickly, and measured initiation speed. Section B required completing the sentence with an unconnected word quickly, and measured response suppression. Response speed on both sections and errors on Section 2 were used to derive an overall scaled score for each participant on a scale ranging from 1 (impaired) to 10 (very superior).

Stroop test

This task taps inhibitory processes by requiring the respondent to ignore the automatic response of reading a printed word and to instead name the color of ink in which the word is printed (Taylor, Kornblum, Lauber, Minoshima, & Koeppe, 1997). In Part A, the participant named as quickly as possible the color of 24 dots printed in blue, green, red, or yellow. Part B was similar to Part A except that the dots were replaced by common (noncolor) words (e.g., when, hard, and over), printed in lower case. The respondent was instructed to name the color in which the word was printed and to ignore the verbal content. In Part C, the colored stimuli were the color names (i.e., blue, green, red, and yellow) printed in lower case with the ink color being incongruent to the color name. The performance score was the interference index and reflected slowing in response to interference in Part C ([Part Ctime – Part Atime]/Part Atime). Lower scores indicated better performance.

Brixton spatial anticipation test

This task (Bielak et al., 2006; Burgess & Shallice, 1997) was a rule-attainment (or shifting) task based on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (Berg, 1948). Participants are required to deduce simple and changing patterns, measuring their ability to abstract logical rules (Andrés & Van der Linden, 2000). The total errors were recorded and these errors (maximum 54) were converted to scaled scores. An overall standardized scaled score based on a scale ranging from 1 (impaired) to 10 (very superior) was used for analysis.

Color trails test (Part 2 CTT-2)

Indexing shifting, the CTT (D’Elia, Satz, Uchiyama, & White, 1996) was similar to the Trail Making Test (Reitan & Wolfson, 1992) but minimized the influence of language. Part 2 required participants to connect numbers from 1 to 25 alternating between pink and yellow circles and disregarding the numbers in circles of the alternate color. The latency score for Part 2 was used for analysis. Lower scores indicate better performance.

Pulse Pressure

Pulse pressure (PP), a reliable proxy of the arterial stiffness aspect of vascular health, is calculated as follows: PP = systolic – diastolic blood pressure. For all analyses PP was used as a continuous variable and was centered at 52 mmHg, the approximate population mean at baseline. For the current study, we wished to develop a sample of typically aging older adults and thus those with self-reported high blood pressure and blood pressure medication were included in the analyses. Serious high blood was reported at baseline by only 5 participants (0.8% of the sample) and blood pressure medication use was reported by n=158 (26.4% of the sample).

DNA Extraction and Genotyping Saliva Collection

Saliva was collected according to standard procedures from Oragene-DNA Genotek and stored at room temperature in the Oragene® disks until DNA extraction. DNA was manually extracted from the saliva sample mix using the manufacturer's protocol and quantified using a NanoDrop® ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Wilmington, DE). Genotyping was carried out by using a PCR-RFLP strategy to analyze the allele status for IDE (rs6583817). Briefly, SNP-containing PCR fragments were amplified from 25 ng of genomic DNA using specific primers (Fwd: 5’-AATATATGGGCAAATATTAAGTGCAC-3’; Rev: 5’-CAGTTGTGGGAATATATTCCTGAG-3’). Reactions were set up in 96-well plates using the QIAgility robotic system (QIAgen). RFLP analysis was performed on a high resolution DNA screening cartridge on a QIAxcel capillary electrophoresis system (QIAgen) using the protocol OL700 after digestion of the PCR amplicons with the restriction enzymes DdeI (NE Biolabs) for 4 hours at 37°C. The analysis was confirmed upon migration of the restriction fragments on 10 or 15% acrylamide gels for the SNP.

For genetic analyses the IDE genotypes were categorized by the presence of an A allele (A+ = A/A, homozygous minor allele, and G/A, heterozygous allele) or the absence of an A allele (A- = G/G, homozygous major allele). For the A+/A- allele analyses, no effect on EF performance was observed (EF performance at age 75 years p > .05; EF change p > .05); therefore, the alternative configuration (presence or absence of a G allele) was used for analyses. Therefore, IDE genotypes were categorized by the presence of a G allele (G+ = G/G, homozygous major allele, and G/A, heterozygous allele) or the absence of a G allele (G- = A/A, homozygous minor allele). See Table 2 for descriptive statistics by IDE allele and wave. Although there are several potentially interesting IDE variants in this emerging literature, this is the one available in the VLS.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Sample by IDE genotype and Longitudinal Wave

| IDE genotype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G+ (G/G & G/A) | G- (A/A) | |||||

| W1 | W2 | W3 | W1 | W2 | W3 | |

| na | 519 | 427 | 255 | 79 | 63 | 23 |

| Age | 70.1 (8.52) | 74.2 (8.40) | 74.7 (6.98) | 73.4(8.73) | 77.9 (8.62) | 76.8 (9.00) |

| Range | 58.0–82.9 | 57.2–94.1 | 62.4–92.9 | 54.6–90.7 | 58.9–94.5 | 63.2–94.9 |

| Gender (% women) | 67.1 | 67.0 | 67.5 | 59.5 | 55.6 | 60.9 |

| Pulse Pressure | 51.8 (10.5) (8.75) | 55.4 (13.1) | 55.1 (12.4) | 55.0 (16.5) | 57.1 (11.5) | 58.4 (12.1) |

| Range | 32.8–99.2 | 26.2–120.9 | 29.0–95.5 | 33.8–171.4 | 33.8–82.0 | 38.6–80.2 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 127.3 (21.6) | 127.1 (16.0) | 126.6 (14.8) | 128.7 (20.3) | 129.8 (15.0) | 130.5 (15.3) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 75.6 (19.2) | 71.8 (9.05) | 71.6 (8.53) | 73.7 (9.54) | 72.7 (9.24) | 71.9 (8.17) |

| Hayling | 5.57 (1.46) | 5.45 (1.51) | 5.61 (1.37) | 5.39 (1.41) | 5.28 (1.31) | 5.13 (1.60) |

| Stroopb | 1.28 (.737) | 1.33 (.923) | 1.21 (.727) | 1.44 (.876) | 1.54 (1.07) | 1.39 (.674) |

| Brixton | 4.89 (2.16) | 5.42 (2.00) | 5.64 (1.93) | 4.53 (2.19) | 4.91 (2.19) | 5.45 (2.02) |

| Color Trailsb | 92.9 (29.2) | 99.8 (39.0) | 100.7 (38.7) | 103.4 (39.6) | 109.2 (42.2) | 99.3 (31.9) |

| EF factor scores | .014 (.823) | .082 (1.19) | .442 (.956) | −.277 (.932) | −.301 (1.32) | .177 (1.02) |

Note. Results presented as Mean (Standard Deviation) unless otherwise stated. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium χ2 = 54.09 at W1, therefore the genotypic distribution for IDE is not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. W1 = Wave 1. W2 = Wave 2. W3 = Wave 3.

For G+ n is for total G (G/G & G/A).

Lower scores indicate better performance.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses pertaining to our research questions included confirmatory factor analysis and latent growth modeling. Statistical model fit for all analyses was determined using standard indexes: (a) χ2 for which a good fit would produce a non-significant test (p > .05) indicating that the data are not significantly different from the estimates associated with the model, (b) the comparative fit index (CFI) for which fit is judged by a value of ≥ .95 as good and ≥ .90 as adequate, (c) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) for which fit is judged by a value of ≤ .05 as good and ≤ .08 as adequate, and (d) standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) for which fit is judged by a value of ≤ .08 as good (Kline, 2011).

Research Goals (RG)

RG 1: EF Latent Model and 3-wave Invariance Testing

First, we used Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010) to conduct confirmatory factor analysis. We tested two models (a) a single factor model and (b) a 2-factor model consisting of inhibition (Hayling, Stroop) and shifting (Brixton, CTT). Second, we tested longitudinal (three-wave) measurement invariance including (a) configural invariance, for which the same indicator variables load onto the latent variable used to test the model across time, (b) metric invariance, for which factor loadings are constrained to be equal for each latent variable indicating that the latent variable is measuring the same construct, (c) scalar invariance, for which indicator intercepts are constrained to be equal allowing mean differences to be evident at the latent mean level, and (d) residual invariance, for which indicator residuals are constrained to be equal accounting for error variability and thus group differences are based on their common variability. We estimated factor scores for EF in Mplus and used these in subsequent latent growth models. In addition for all further analyses, we used multiple imputations to estimate missing values for pulse pressure, age, and EF factor scores. The procedure stipulated that 50 datasets were generated and pooled before analyses were conducted.

RG 2: Latent Growth Models for EF and PP

We coded age as a continuous factor and computed latent growth models with individually-varying ages. Age was centered at 75 years of age, as this is the approximate center point of the 40 year band of data (i.e., 53–95 years) and because it is an observed meaningful point in cognitive aging (Dixon et al., 2012; Schaie, 2013; Small et al., 2011). We used the best fitting latent model for EF and measures of PP at each of the three waves. To identify the functional form of change, we determined the best-fitting unconditional growth model by testing in sequence: (a) a fixed intercept model, which assumes no inter- or intraindividual variation; (b) a random intercept model, which models interindividual variability in overall level but no intraindividual change; (c) a random intercept fixed slope model, which allows interindividual variation in level but assumes all individuals change at the same rate; and (d) a random intercept random slope model, which models interindividual variation in initial level and change (Singer & Willett, 2003). Maximum likelihood estimation was used for these and all subsequent models in order to permit statistical tests of fixed and random effects (Singer & Willett, 2013). The deviance statistic was used to compare nested models.

RG 3 and RG4: Conditional Growth Models using PP and IDE (RG3) and PP Moderation Effects on IDE-EF Relationship (RG4)

Using the best unconditional growth model identified for EF, predictors of change were added to the model. The intercept and slope were regressed separately on IDE genotype and PP measured at W1. Next, in order to test the moderation effects of the IDE-EF relationship, we used a conditional growth model for EF with PP as a predictor using the two IDE genotype groups (G+/G-).

Results

Following the analyses reported in this section we tested the potential role of reported use of blood pressure medication as a covariate in the models. Consistently, all model fit statistics were significantly poorer with no changes to the observed result patterns. Therefore, analyses leading to the following results do not include this covariate.

RG 1: EF Latent Model and 3-wave Invariance Testing

Using confirmatory factor analysis we tested two EF models. The one-factor model of EF fit the data well for W1, W2, and W3. In contrast, the two-factor model could not be estimated at any of the three waves, resulting in the absence of a positive definite variance-covariance matrix (see Table 3 for model goodness of fit indexes). Therefore, as observed in earlier VLS research with different samples (e.g., de Frias et al., 2006, 2009) we accepted the single-factor model for normal older adults. Next, we conducted invariance testing on the single-factor model. The model holding indicator factor loadings equal across W1, W2, and W3 fit the data well, thus indicating metric invariance. Fixing intercepts to be equal across time resulted in significantly poorer fit to the data according to the χ2 difference test. We conducted tests of partial scalar invariance by freeing intercepts for each indicator in turn. These analyses supported partial scalar invariance for Hayling. Overall, we observed metric invariance for the single-factor EF model and partial scalar invariance indicating that this model measured the same EF construct across time, but the manifest variables marking EF, except Hayling, exhibited mean differences across time outside of the latent differences.

Table 3.

Goodness of Fit Indexes for Executive Function Confirmatory Factor Analysis Models and Measurement Invariance Testing

| AIC | BIC | χ2 | df | p | RMSEA | CFI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | ||||||||

| One factor EF (W1) | 9442.891 | 9491.202 | 32.502 | 3 | <.000 | .128 (.019–.170) | .786 | .121 |

| Two factor EFa (W1) | Non-positive definite. | |||||||

| One factor EF (W2) | 8079.871 | 8126.009 | 10.951 | 3 | .0120 | .074 (.030–.123) | .963 | .088 |

| Two factor EFa (W2) | Non-positive definite. | |||||||

| One factor EF (W3) | 4376.223 | 4416.245 | 9.987 | 3 | .0187 | .091 (.033–.156) | .919 | .088 |

| Two factor EFa (W3) | Non-positive definite. | |||||||

| One factor EF (W1, W2, W3) | 20862.182 | 21077.468 | 62.349 | 41 | .0174 | .030 (.013–.044) | .985 | .078 |

| Equal indicator loadingsb | 20865.389 | 21080.675 | 65.556 | 41 | .0088 | .032 (.016–.045) | .983 | .086 |

| Equal intercepts | 20970.994 | 21159.919 | 183.161 | 47 | <.001 | .070 (.059–.080) | .907 | .110 |

| Equal intercepts STRP & HAY | 20868.560 | 21075.059 | 72.727 | 43 | .0031 | .034 (.020–.047) | .980 | .089 |

Note. AIC = Akaike information criteria. BIC = Bayesian information criteria. RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation. CFI = Comparative Fit Index. SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual. EF = Executive Function. W1 = Wave 1. W2 = Wave 2. STRP = Stroop. HAY = Hayling.

Model not identified.

Best fitting model used for Factor Score Analysis.

RG 2: Latent Growth Models for EF and PP

Executive function (EF)

Using age (centered at 75) as the metric of change, we performed latent growth modeling using estimated EF factor scores. The best fitting unconditional growth model for EF was established as a random intercept, random slope latent growth model (see Table 4 for model goodness of fit indexes). First, this model indicated that older adults significantly vary in EF performance at age 75 (b = 1.16, p < .001). Second, the model revealed a significant decline in EF performance across time (M = −.011, p <.001). Third, older adults showed significantly variable patterns of decline (b = .002, p < .001).

Table 4.

Absolute Fit Indexes for Executive Function and Pulse Pressure Latent Growth Models

| Model | -2LL | AIC | BIC | D | Δdf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive Function (EF) | |||||

| Fixed intercept | 4003.216 | 4007.217 | 4003.216 | - | - |

| Random intercept | 2522.664 | 2528.664 | 2541.844 | 1480.5 | 1* |

| Random intercept Fixed slope |

2499.658 | 2507.657 | 2525.231 | 23.0 | 1* |

| Random intercept Random slopea |

1811.242 | 1823.242 | 1849.603 | 688.4 | 2* |

| Pulse Pressure (PP) | |||||

| Fixed intercept | 6133.836 | 6141.836 | 5952.256 | - | - |

| Random intercept | 5591.604 | 5601.604 | 5623.572 | 540.2 | 1* |

| Random intercept Fixed slopea |

5241.314 | 5253.314 | 5279.675 | 348.29 | 1* |

| Random intercept Random slopeb |

5207.978 | 5223.977 | 5259.126 | 29.3 | 2* |

Note. −2LL = −2 log likelihood; AIC =Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; D = deviance statistic; df = degrees of freedom.

Preferred model.

The variance of the slope was not significant, therefore this model was not retained despite the significant deviance test.

p <.001.

Pulse Pressure (PP)

Using age (centered at 75) as the metric of change, we performed latent growth modeling using PP measures at each wave. For PP the preferred model was a random intercept, fixed slope model (see Table 4 for model goodness of fit indexes). First, this model indicated that at age 75 years adults have levels of PP that are significantly different from the centering point of 52 mmHg (M = .299, p <.001). Second, older adults showed significant variation in PP level (b = .813, p <.001). Third, there was a significant increase in PP across time (M = .053, p <.001) for this older adult group, which was similar across individuals.

RG 3: Conditional Growth Models Using PP and IDE

PP

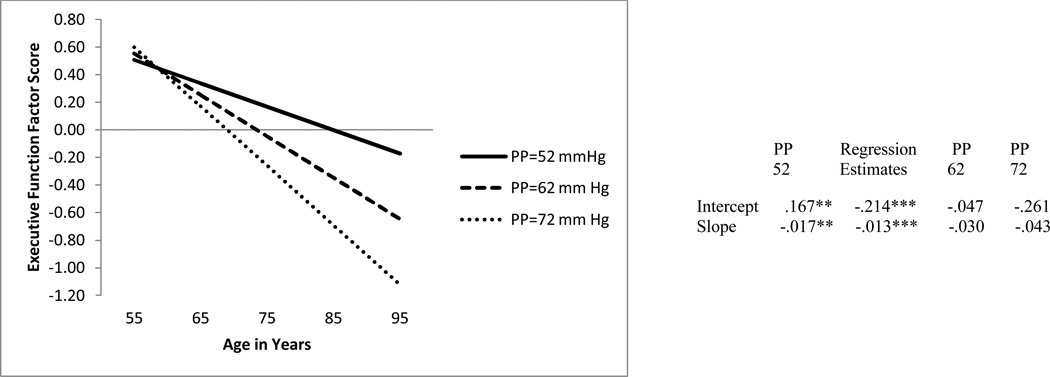

We tested two conditional growth models with PP as a predictor of EF level and change. The first model used the PP growth model in parallel process with EF growth model. Notably, time-varying PP did not significantly predict EF performance at age 75 (b = −.071, p > .05) nor did time-varying PP predict three-wave change in EF performance (b = −.001, p > .05). Therefore, we next tested a model in which the initial level of PP (at W1) was used as a predictor of both EF performance at age 75 and three-wave EF change (see Table 5). This model revealed two important findings. First, it showed that lower initial levels of PP, centered at the group mean of 52, resulted in significantly better EF (p < .001). Second, lower initial PP levels predicted less 9-year EF decline (p < .001, see Figure 1). Specifically, adults with PP at the centering point (i.e., PP = 52 mmHg) had better EF performance (M = .167) than adults PP above the centering level (EF M = −.047). Moreover, adults with PP at the centering point exhibited significantly less longitudinal decline in EF (M = −.017) than adults with higher PP levels (EF M = −.030).

Table 5.

Absolute Fit Indexes for Executive Function Conditional Latent Growth Models

| Model | -2LL | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted by PP (W1) | 2171.26 | 2187.26 | 2222.41 |

| Predicted by IDE (G+/G-) | 2207.24 | 2223.24 | 2258.39 |

| Predicted by PP (W1) for IDE (G+/G-) group |

2153.40 | 2185.40 | 2255.70 |

Note. −2LL = −2 log likelihood; AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

Figure 1.

Predicted growth curve for executive function factor scores using pulse pressure (PP, measured in mm Hg) at W1 as a predictor with age as a continuous variable centered at 75 years. *p < .05. **p <.01.***p <.001.

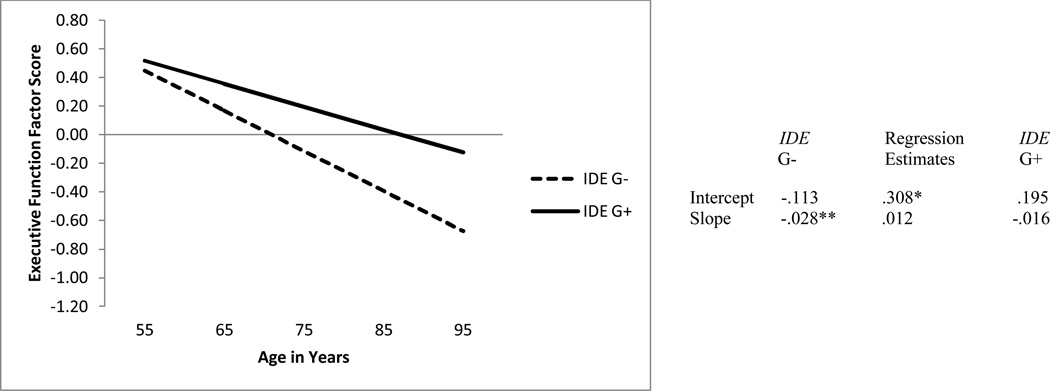

IDE (rs6583817)

We tested IDE as a predictor of EF level at age 75 and rate of EF change (see Table 5). Two interesting results were observed. First, IDE significantly predicted the level of EF performance at age 75 years (p < .05). Specifically adults with a G allele (the G+ group) had better EF performance (M = .195) than adults without a G allele (EF M = −.113; see Figure 2). Second, IDE genotype did not significantly predict the rate of EF change (b = .012, p > .05). The observed slope was in the expected direction, but somewhat lower than that observed in a previous 2-wave study (i.e., b =.018, p = .027, McFall et al., 2013).

Figure 2.

Predicted growth curve for executive function factor scores using IDE genotype (i.e., G- = no G allele, G+ = at least one G allele) as a predictor with age as a continuous variable centered at 75 years. *p < .05. **p <.01.

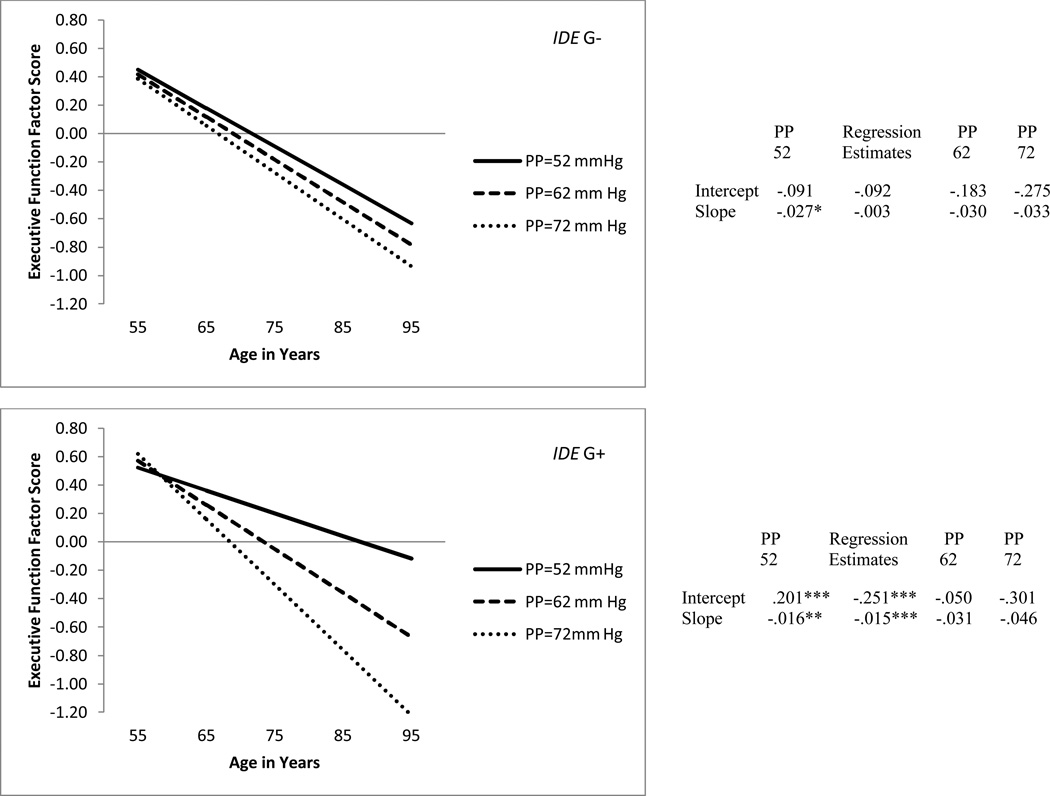

RG 4: PP Moderation Effects on IDE-EF Relationship

In order to examine our moderation hypothesis, we tested a model in which PP at W1 predicted (a) level of EF at age 75 and (b) three-wave change in EF over time based on the IDE G allele groupings (G+/G-; see Table 5). The pattern of results confirmed the moderation hypothesis. First, PP significantly predicted both level of EF (b = −.251, p < .001) and three-wave change in EF (b = −.015, p < .001) for the G+ group. Second, in contrast, PP did not significantly predict level of EF (b = −.092, p>.05) or change in EF (b = −.003, p>.05) for the G- group. This interaction, which demonstrates moderation by IDE genotype, is displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Predicted growth curve for executive function factor scores by IDE genotype (i.e., G- = no G allele, G+ = at least one G allele) using pulse pressure as a predictor with age as a continuous variable centered at 75 years. *p < .05. **p <.01. ***p <.001.

Discussion

The goal of this research was to explore the independent and interactive effects of one modifiable vascular health factor (PP) and one genetic polymorphism (IDE [rs6583817]) on EF performance and change patterns across three waves of data in a group of older adults. For Research Goal 1 (EF latent model and 3-wave invariance testing), we observed two main and expected findings: (a) a one-factor model of EF provided the best fit to the data for this large group of normal aging adults and (b) this one-factor model demonstrated both metric and partial scalar invariance over the three longitudinal waves. The unidimensional EF structure has been observed in our previous work with normal aging groups (de Frias et al., 2006) and was also reported for a mild cognitive impairment group (de Frias et al., 2009). In the latter study the single-factor representation was one of two models that fit the EF data for a comparison group characterized as cognitively elite older adults, so it is widely applicable to normal aging. In the present study we used two aspects of EF; updating may be incorporated into this line of research in the future but no basic measurement differences would be expected.

For Research Goal 2 (latent growth models for EF and PP), we observed several interesting findings. Regarding the growth models for EF, we detected: (a) a significant amount of variability in EF performance at the centering age of 75 years, (b) a significant decline across 9 years, and (c) a significant degree of variability in the trajectory of decline in EF over the 9 years. The fact of concurrent and change-related variability—combined with the general trajectory of decline—points to the potential operation of selective and individualized risk or protection factors. These may include elements of biological vulnerability, health burden, or lifestyle supports or compromises—all of which may operate independently or in combination to produce differential EF performance and long-term change in normal aging (Dixon, 2011; Lindenberger et al., 2008; Fotuhi et al., 2009). These results are integral to the further research goals of this study. Regarding the growth models for PP, we observed (a) a significant amount of variability in PP level at the centering age of 75 years and (b) a significant increase in PP over the 9 years that was at a consistent rate for all adults in the sample. The increase in PP observed in this sample is in agreement with other studies indicating general age-related decreases in vascular health (Dahle et al., 2009; Davenport, Hogan, Eskes, Longman, & Poulin, 2012; Franklin et al, 1997; Raz et al., 2011).

For Research Goal 3, we tested conditional growth models using PP and IDE in order to examine the independent effects of these factors on EF performance and change. We found a series of interesting results. First, older adult carriers of an IDE G allele were advantaged in EF performance (at the centering age of 75 years) as compared with those with the AA allele combination (homozygotes). Second, IDE genotype predicted level of EF performance, but not rate of change in this group of normal older adults. In the only previous study of which we are aware, we observed the same results for the concurrent association test, but apparently different results for the rate of change tests (McFall et al., 2013). In that study, older adults with a G allele (i.e., G+ group) experienced lower decline than those without a G allele over two waves of measurement. A likely qualification and explanation for this variation in results is evident. The slope values are not dramatically different: The two-wave slope data for the G+ group from the earlier study indicated b=.018 (p=.027) whereas the present three-wave slope was slightly lower b=.012 (p> .05). There could indeed be real adjustments in the effects of IDE-specific modification of EF slope over longer (about 9 years), as compared with shorter (about 4 years) periods of aging. Further longitudinal work—combined with other key genetic variants related to EF or general cognitive integrity—may shed light on the longer term prospects for the aging functions of EF. It is also possible that an unavoidable methodological characteristic of the present design influenced this slight shift in slope. As we noted above, in the present study the third wave of data was restricted to one of the three contributing VLS samples. This resulted in relatively fewer than expected participants in wave 3, but also a slightly younger than expected age range. It is therefore possible that the minor leveling off of the slope occurred between W2 and W3 and was related to the corresponding leveling off of the age range of the third wave. These substantive and methodological facts will be evaluated using upcoming new longitudinal data. For now, this interpretive uncertainty is not critical to the next (fourth) research goal. One other result pertaining to Research Goal 3 should be noted: We found evidence that adults with higher PP experienced decreased EF performance at age 75 and more decline over time. The best PP-related predictor and moderator of EF performance and change was the initial level of PP (at baseline). Time-varying PP was not related to time-varying EF in this study. Although PP varied over waves, it may not have varied dramatically enough to differentially affect EF change.

Unique to this research was the opportunity to examine a potential PP moderation of the IDE-EF relationship as pursued in Research Goal 4. The results (see Figure 3) show that indeed baseline PP (centered at 52mm Hg) moderated the IDE-EF relationship. Specifically using G+/G- grouping and at the centering age of 75, the G+ group had higher EF performance than did the G- group. When PP was added to this model as a predictor, group results were indeed different. For the IDE G- group PP did not significantly alter either the level of EF performance at age 75 or 9-year EF change. In contrast, adults in the G+ group exhibited a different pattern. Specifically, adults with a G allele and lower levels of PP had higher levels of EF performance at age 75 and less 9-year EF change. As PP increased, the G+ group exhibited significant EF changes—viz., a decrease in EF performance at age 75, when compared to their healthier (in terms of PP) counterparts, and a more pronounced EF 9-year decline. In fact, adults at a high average PP (i.e., 72 mm Hg) showed an increase in EF decline, in a pattern similar to that displayed by adults without the protective IDE G allele. Overall, the results of the RG4 analyses show the important result that older adults with a G+ allele produce the best EF group performance, both concurrently and over time—if they also have healthier levels of PP. In contrast, adults with the G+ allele and less healthy levels of PP experience detrimental cognitive effects, as shown by decrements in EF performance at age 75 years and a steeper decline in EF over 9 years. A growing number of studies have reported results supportive of a perspective sometimes referred to as a differential-susceptibility hypothesis (e.g., Belsky et al., 2009). Although often rendered in terms of gene-environment interactions—with environment referring to a variety of extra-personal and other influences—we observed consistent results in a specific interaction between a selected genetic variant and a basic biological-health influence. More specifically, older adults possessing the IDE (rs6583817) major (G) allele are particularly susceptible to health-environmental factors, perhaps especially some vascular health markers such as PP (e.g., Davenport et al., 2012; Fotuhi et al., 2009; Raz et al., 2009; Raz et al., 2011; Song et al. 2011). Notably, from a clinical and public health perspective, these results appear not in cognitively impaired or highly at risk (e.g., for dementia) patients, but for normal older adults, with varying but generally typical or managed ranges of PP.

Among the other (and unmeasured in this study) factors that could affect the degree of decline or preservation of EF performance in older adults are changes in insulin resistance in the brain (see Biessels et al., 2008; Craft et al., 2004, for potential biological mechanisms). The IDE (rs6583817) minor (A) allele has been reported to increase the amount of IDE expression, resulting in a decrease in insulin and Aβ (Carrasquillo et al., 2010). As noted by other researchers (Belbin et al., 2011; Carrasquillo et al., 2010), this could result in a lowered risk of Alzheimer’s disease and conceivably, due to decreased insulin in the brain, lower cognitive abilities. According to this model, the IDE major (G) allele is related to a decrease in IDE expression resulting in an increase of insulin in the brain. Increases in insulin have been linked to increases in cognitive performance and indeed insulin may become even more important to cognitive performance with advancing age (Awad et al., 2004; Seaquist et al., 2012). Decreases in EF performance have been linked to reduced cerebral blood flow and white matter lesions where the prefrontal cortex is especially vulnerable (Raz, et al., 2003; Saxby, Harrington, McKeith, Wesnes, & Ford, 2003; Waldstein et al., 2008). The increased insulin level associated with the IDE G+ allele may account for some of the cognitive preservation observed with normal aging (Raz et al., 2003) but poorer vascular health as measured by PP may increase cognitive vulnerability to the point that even preserved or enhanced insulin levels can no longer provide sufficient support (Craft et al., 2004).

As has been suggested in multiple domains, the present research confirms that maintenance of vascular health is essential for cognitive health in older adulthood (Colcombe et al., 2003; Elias et al., 2004; Qiu et al., 2005; Waldstein et al., 2008). Although vascular health is a relatively modifiable risk factor in neurocognitive aging, both hypertension medication and lifestyle choices (e.g., physical exercise, diet) require extended compliance and may vary in their effects by endemic factors (e.g., gender; Davenport et al., 2012). In this study we observed that one of the conditions may also be basic and unmodifiable genetic factors. Specifically, PP interacts in its effect on EF performance and long-term change with a recently identified genetic polymorphism of growing interest across the spectrum of normal aging to Alzheimer’s disease. Further research on the interactions of such varied conditions as lifestyle activities and genetic factors may further clarify their combinatorial roles in neurocognitive aging (Fotuhi et al., 2009; Colcombe et al., 2003; Raz et al., 2003).

There are several limitations and strengths associated with this study. First, the VLS has only one of several IDE genotypes that could be associated with neurodegenerative diseases (i.e., Alzheimer’s and related disorders) and cognitive-related health conditions (i.e., T2D). This particular genotype (rs6583817) has just recently been investigated in relation to AD but has been relatively unexplored in regard to normal cognitive aging. Although the results of research with this polymorphism are very promising, a broader representation of the IDE group would be valuable for future research. Second, this study considers arterial stiffness, which is one aspect of the larger domain of vascular health and is associated with cognitive performance in older adults. Although a direct measure of arterial stiffness (pulse wave velocity) is not available in the VLS, systolic and diastolic blood pressure are available and therefore the recommended proxy of pulse pressure was used. The effect of vascular health and genetics on cognition in older adults would benefit from a broader representation of normal and clinical vascular health. Third, the present sample is relatively large and covers three waves over about 9 years, but a design characteristic should be noted, as it affected the n and age characteristics of W3. The design characteristic is that at the time of this study (a) S1 and S2 have not yet been tested on their corresponding W3 and (b) only S3 contributed to W3. Attrition rates for each definable interval (two waves of data on the same sample) were reported and excellent—and the accelerated longitudinal approach was successful—but a more complete design would have included some W3 participants from all three samples. Notably, however, this design characteristic did not seem to affect the results: From the invariance testing to the change-related analyses, the 3-wave data were quite informative. One potential and slight leveling effect was noticed and reported and should be investigated further in future research. Fourth, our study is designed to evaluate the effects of genetics and health factors in a relatively normal older adult sample. To represent typical aging, we deliberately included older adults with varying levels of blood pressure and even self-reported hypertension medication. In general, at intake, the VLS samples are designed to be relatively healthy (e.g., free of known neurodegenerative disease), community dwelling, and broadly educated. The goal is to observe aging-related changes in biological and neurological health and evaluate their impact on cognitive performance and change. We note, however, that all participants have access to national health care. Although this group may not be representative of all older adults, it may represent a conservative estimation of the moderation effects of environmental factors (i.e., aspects of vascular health) on genetic-cognition relationships.

There are also several strengths associated with this study. First we used contemporary statistical approaches to analyze a series of research goals that systematically built the case for the final set of analyses. Second, we examined the effect of continuously measured age in an accelerated longitudinal design that allowed us to look at the effects of PP and IDE (rs6583817) across three data collection points spanning about 9 years. Third, our sample was relatively large (i.e., W1 n = 598) and well-characterized. That this group comprised a band of 40 years of aging is important to note. Fourth, our EF latent variable was composed of four standard and strong neuropsychological manifest variables. Fifth, we examined a novel genetic variant, related to vascular disease and AD, in a relatively healthy group of older adults. We observed potentially protective effects in normal neurocognitive aging.

In conclusion, the goal of this study was to examine the independent and interactive effects of vascular health, as measured by PP and IDE (rs6583817) on EF level for both (a) a centering age of 75 years and (b) change across about 9 years. Whereas the IDE (rs6583817) major (G) provided apparent protection from the decrements in EF associated with aging, decreased vascular health had a detrimental effect on EF patterns. Furthermore, the protective effects of the G allele were strongly influenced by the negative effects of decreasing vascular health. This fact may imply that the maintenance of vascular health is even more important for adults who possess specific allelic combinations of key cognitive aging genes (e.g., IDE, rs6583817). Future research will determine the extent to which vascular health—and potentially numerous other aging-related health factors—may have substantial direct and moderating influences on cognitive phenotypes of aging.

Acknowledgments

The present research is supported by grants from (a) the National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Aging; R01 AG008235) to author RAD and (b) the Alberta Health Services (University Hospital Foundation) to authors DW, JJ, and RAD. Both RAD and DW are also supported by the Canada Research Chairs program. We thank the volunteer participants and the VLS staff for their many contributions. We acknowledge the University of Alberta Centre for Prions and Protein Folding Diseases for laboratory and technical support. We acknowledge the specific contributions of Correne DeCarlo, Stuart MacDonald, and Bonnie Whitehead to the VLS genetics initiative. More information about the VLS may be found at: http://www.ualberta.ca/~vlslab/.

References

- Andrés P, Van der Linden M. Age-related differences in supervisory attentional system functions. Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2000;55:373–380. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.p373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstey K, Christensen H. Education, activity, health, blood pressure, and apolipoprotein E as predictors of cognitive change in old age: A review. Gerontology. 2000;46:163–177. doi: 10.1159/000022153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad N, Gagnon M, Messier C. The relationship between impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes, and cognitive function. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2004;26:1044–1080. doi: 10.1080/13803390490514875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartl J, Scholz C-J, Hinterberger M, Jungwirth S, Wichart I, Rainer MK, Grunblatt E. Disorder-specific effects of polymorphisms at opposing ends of the insulin degrading enzyme gene. BioMed Central Medical Genetics. 2011;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-151. Accessed at www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/12/151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belbin O, Crump M, Bisceglio GD, Carrasquillo MM, Morgan K, Younkin SG. Multiple insulin degrading enzyme variants alter in vitro reporter gene expression. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Jonassaint C, Pluess M, Stanton M, Brummett B, Williams R. Vulnerability genes or plasticity genes? Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14:746–754. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RG, Duckworth WC, Hamel FG. Degradation of amylin by insulin-degrading enzyme. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:36621–36625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006170200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg EA. A simple objective technique for measuring flexibility in thinking. The Journal of General Psychology. 1948;39:15–22. doi: 10.1080/00221309.1948.9918159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielak AAM, Mansueti L, Strauss E, Dixon RA. Performance on the Hayling and Brixton tests in older adults: Norms and correlates. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2006;21:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biessels GJ, Deary IJ, Ryan CM. Cognition and diabetes: A lifespan perspective. Lancet Neurology. 2008;7:184–190. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist ME-L, Chalmers K, Andreasen N, Bogdanovic N, Wilcock GK, Cairns NJ, Prince JA. Sequence variants of IDE are associated with the extent of β-amyloid depsosition in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiology of Aging. 2005;26:795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainerd CJ, Reyna VF, Petersen RC, Smith GE, Taub ES. Is the Apolipoprotein E genotype a biomarker for mild cognitive impairement? Findings from a nationally representative study. Neuropsychology. 2011;25:679–689. doi: 10.1037/a0024483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW, Shallice T. The Hayling and Brixton tests. Thurston, Suffolk, England: Thames Valley Test Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquillo MM, Belbin O, Zou F, Allen M, Ertekin-Taner N, Ansari M, … Morgan K. Concordant association of insulin degrading enzyme gene (IDE) variants with IDE mRNA, Aβ, and Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombe SJ, Erickson KI, Raz N, Webb AG, Cohen NJ, McAuley E, Kramer AF. Aerobic fitness reduces brain tissue loss in aging humans. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 2003;58A:176–180. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.2.m176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft S, Watson GS. Insulin and neurodegenerative disease: Shared and specific mechanisms. The Lancet Neurology. 2004;3:169–178. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00681-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahle CL, Jacobs BS, Raz N. Aging, vascular risk, and cognition: Blood glucose, pulse pressure, and cognitive performance in healthy adults. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:154–162. doi: 10.1037/a0014283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart AM, Kingwell BA. Pulse pressure - a review of mechanisms and clinical relevance. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001;4:975–984. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport MH, Hogan DB, Eskes GA, Longman RS, Poulin MJ. Cerebrovascular reserve: The link between fitness and cognitive function? Exercise and Sports Science Reviews. 2012;40(3):153–158. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3182553430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ, Wright AF, Harris SE, Whalley LJ, Starr JM. Searching for genetic influences on normal cognitive aging. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2004;8(4):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Elia LF, Satz P, Uchiyama CL, White T. Color Trails Test: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- de Frias CM, Dixon RA, Strauss E. Structure of four executive functioning tests in healthy older adults. Neuropsychology. 2006;20:206–214. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Frias CM, Dixon RA, Strauss E. Characterizing executive functioning in older special populations: From cognitively elite to cognitively impaired. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:778–791. doi: 10.1037/a0016743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA. Enduring theoretical themes in psychological aging: Derivation, functions, perspectives, and opportunities. In: Schaie KW, Willis SL, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 7th ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, de Frias CM. The Victoria Longitudinal Study: From characterizing cognitive aging to illustrating changes in memory compensation. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2004;11:346–376. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Small BJ, MacDonald SWS, McArdle JJ. Yes, memory declines with aging - but when, how, and why? In: Naveh-Benjamin M, Ohta N, editors. Memory and aging. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Elias PK, Elias MF, Robbins MA, Budge MM. Blood pressure-related cognitive decline: Does age make a difference? Hypertension. 2004;44:631–636. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000145858.07252.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Analyzing longitudinal data with missing values. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2011;56:267–288. doi: 10.1037/a0025579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin S, Gustin W, Wong N, Larson M, Weber M, Kannel W, Levy D. Hemodynamic patterns of age-related changes in blood pressure - The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1997;96:308–315. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotuhi M, Hachinski V, Whitehouse PJ. Changing perspectives regarding late-life dementia. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2009;5:649–658. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Hall CB, Lipton RB, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM, Kawas C. Memory impairment, executive dysfunction, and intellectual decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2008;14:266–278. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haan MN, Shemanski L, Jagust WJ, Manolio TA, Kuller L. The role of APOE ɛ4 in modulating effects of other risk factors for cognitive decline in elderly persons. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:40–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen K, Pettersen E, Stovner LJ, Skorpen F, Holmen J, Zwart J-A. High systolic blood pressure is associated with val/val genotype in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene. American Journal of Hypertension. 2007;20:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SE, Deary IJ. The genetics of cognitive ability and cognitive aging in healthy older people. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011;15:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C. Theoretical approaches to the study of cognitive aging: An individual-differences perspective. In: Hofer SM, Alwin DF, editors. Handbook of cognitive aging Interdisciplinary perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2008. pp. 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kremen WS, Lyons MJ. Behavior genetics of aging. In: Schaie KW, Willis SL, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 7th ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kurochkin IV, Goto S. Alzheimer’s β-amyloid peptide specifically interacts with and is degraded by insulin degrading enzyme. Federation of European Biochemical Societies Letters. 1994;345:33–37. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00387-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger U, Nagel IE, Chicherio C, Li S-C, Keekeren HR, Bäckman L. Age-related decline in brain resources modulates genetic effects on cognitive functioning. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2008;2(2):234–244. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.039.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luszcz M. Executive function and cognitive aging. In: Schaie KW, Willis SL, editors. The handbook of the psychology of aging. 7th ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mahley RW, Rall SC., Jr. Apolipoprotein E: Far more than a lipid transport protein. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 2000;1:507–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.1.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattace-Raso FU, van der Cammen TJ, Hofman A, van Popele NM, Bos ML, Schalekamp MA, Wotteman JC. Arterial stiffness and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: The Rotterdam Study. Circulation. 2006;113:657–663. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.555235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall GP, Wiebe SA, Vergote D, Westaway D, Jhamandas J, Dixon RA. IDE (rs6583817) polymorphism and type 2 diabetes differentially modify executive function in older adults. Neurobiology of Aging. 2013;34:2208–2216. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GF, Vasan RS, Keyes MJ, Parise H, Wang TJ, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ. Pulse pressure and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297:709–715. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology. 2000;41:49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan J, Wilkinson D, Stammers S, Low L. The role of tests of frontal executive function in the detection of mild dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;16:18–26. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200101)16:1<18::aid-gps265>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel IE, Chicherio C, Li S-C, von Oertzen T, Sander T, Villringer A, Lindenberger U. Human aging magnifies genetic effects on executive functioning and working memory. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2008;2:1–8. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.001.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WQ, Folstein MF. Insulin, insulin-degrading enzyme and amyloid-β peptide in Alzehimer’s disease: Review and hypothesis. Neurobiology of Aging. 2006;27:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu C, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. The age-dependent relation of blood pressure to cognitive function and dementia. Lancet Neurology. 2005;4:487–499. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu C, Winblad B, Viitanen M, Fratiglioni L. Pulse pressure and risk of Alzheimer disease in persons aged 75 years and older: A community-based, longitudinal study. Stroke; a Journal of Cerebral Circulation. 2003;34:594–599. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000060127.96986.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp MA, Reischies FM. Attention and executive control predict Alzheimer disease in late life: Results from the Berlin Aging Study (BASE) American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13:134–141. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Dahle CL, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Land S. Effects of age, genes, and pulse pressure on executive functions in healthy adults. Neurobiology of Aging. 2011;32:1124–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Rodrigue KM, Acker JD. Hypertension and the brain: Vulnerability of the prefrontal regions and executive functions. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;117:1169–1180. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Land S. Genetic and vascular modifiers of age-sensitive cognitive skills: Effects of COMT, BDNF, ApoE, and hypertension. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:105–116. doi: 10.1037/a0013487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. Neuropsychological evaluation of older children. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputations for nonresponse in surveys. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Saxby BK, Harrington F, McKeith IG, Wesnes K, Ford GA. Effects of hypertension on attention, memory, and executive function in older adults. Health Psychology. 2003;22:587–591. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. Developmental influences on adult intelligence. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin EL. Vascular stiffening and arterial compliance. Implications for systolic blood pressure. American Journal of Hypertension. 2004;17:39S–48S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaquist ER, Latteman DF, Dixon RA. Diabetes and the brain: American Diabetes Association Research Symposium. Diabetes. 2012;61:3056–3062. doi: 10.2337/db12-0489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Joachimiak A, Rosner MR, Tang W-J. Structures of human insulin-degrading enzyme reveal a new substrate recognition mechanism. Nature. 2006;443:870–874. doi: 10.1038/nature05143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Small BJ, Dixon RA, McArdle JJ. Tracking cognition-health changes from 55 to 95 years of age. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2011;66B:i153–i161. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small BJ, Dixon RA, McArdle JJ, Grimm KJ. Do changes in lifestyle engagement moderate cognitive decline in normal aging? Evidence from the Victoria Longitudinal Study. Neuropsychology. 2012;26:144–155. doi: 10.1037/a0026579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD. Apolipoproteins and aging: Emerging mechanisms. Ageing Research Reviews. 2002;1:345–365. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Nontraditional risk factors combine to predict Alzeimer disease and dementia. Neurology. 2011;77(3):227–234. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225c6bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staessen JA, Richart T, Birkenhäger WH. Less atherosclerosis and lower blood pressure for a meaningful life perspective with more brain. Hypertension. 2007;49:389–400. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000258151.00728.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern□ng O, Wahlin Ǻ, Adolfsson R, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C, Nilsson L-G. APOE and lipid level synergy effects on declarative memory functioning in adulthood. European Psychologist. 2009;14:268–278. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SF, Kornblum S, Lauber EJ, Minoshima S, Koeppe RA. Isolation of specific interference processing in the Stroop task: PET activation studies. NeuroImage. 1997;6:81–92. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner GR, Spreng RN. Executive functions and neurocognitive aging: Dissociable patterns of brain activity. Neurobiology of Aging. 2012;33:826.el–826.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umegaki H. Neurodegeneration in diabetes mellitus. In: Ahmad HI, editor. Neurodegenerative diseases. New York, NY: Landes Bioscience and Springer Science+Business Media; 2012. pp. 258–265. [Google Scholar]

- Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, Evans JC, O'Donnell CJ, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:1291–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldstein SR, Rice SC, Thayer JF, Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Zonderman AB. Pulse pressure and pulse wave velocity are related to cognitive decline in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Hypertension. 2008;51(1):99–104. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.093674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RL. An application of prefrontal cortex function theory to cognitive aging. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120:272–292. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe SA, Espy KA, Charak D. Using confirmatory factor analysis to understand executive control in preschool children: I. latent structure. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:575–587. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe SA, Sheffield T, Nelson JM, Clark CAC, Chevalier N, Espy KA. The structure of executive function in 3-year-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2010;108:436–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart HA, Roth RM, Saykin AJ, Rhodes CH, Tsongalis GJ, Pattin KA, McAllister TW. COMT Val158Met genotype and individual differences in executive function in healthy adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2011;17:174–180. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710001402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung SE, Fischer AL, Dixon RA. Exploring effects of Type 2 diabetes on cognitive functioning in older adults. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:1–9. doi: 10.1037/a0013849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]