Abstract

Objective

To determine whether utilization of emergency medical service (EMS) can expedite and improve the rate of thrombolytic therapy administration in acute ischemic stroke patients.

Methods

This is a prospective observational study of consecutive patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with an ischemic stroke within 72 hours of symptom onset. Variables associated with early ED arrival (within 3 hours of stroke onset), and administration of thrombolytic therapy were analyzed. We also evaluated the factors related to onset-to-needle time in patients receiving thrombolytic therapy.

Results

From January 1, 2010 to July 31, 2011, there were 1081 patients (62.3% men, age 69.6 ± 13 years) included in this study. Among them, 289 (26.7%) arrived in the ED within 3 hours, and 88 (8.1%) received intravenous thrombolytic therapy. Patients who arrived to the ED by EMS (n=279, 25.8 %) were independently associated with earlier ED arrival (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 3.68, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.54 to 5.33), and higher chance of receiving thrombolytic therapy (adjusted OR = 3.89, 95% CI= 1.86 to 8.17). Furthermore, utilization of EMS decreased onset-to-needle time by 26 minutes in patients receiving thrombolytic therapy.

Conclusion

Utilization of EMS can help acute ischemic stroke patients in early presentation to ED, facilitate thrombolytic therapy, and reduce the onset to needle time.

Keywords: emergency medical service, thrombolytic therapy, stroke

Introduction

Background

It is estimated that 15 million people suffer from stroke, resulting in 5.5 million deaths worldwide annually1, and significant disability-adjusted life-years lost2,3. Thrombolytic therapy has been proved to benefit patients with acute ischemic stroke and current guidelines recommend consideration of thrombolytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke4,5. However, it can only be administered in patients whose stroke onset within 4.5 hours of presentation (h)4,5,6, and thus many patients are excluded from thrombolytic therapy. Pre-hospital delay is the main cause of low rates of thrombolytic therapy7. In Taiwan, only 27% of ischemic stroke patients arrive in the ED within 3 h of stroke onset8, and only 1.5% of patients with ischemic stroke were treated with intravenous thrombolytic therapy between 2006 and 20089. The percentage was lower than that reported by the Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry in the United States (3.0%–8.5%) and the German Stroke Registers Study Group (3.0%)10,11.

In addition, it has been shown that the sooner that thrombolytic therapy is given to stroke patients, the better the functional outcome12,13. The most serious complication of thrombolytic therapy- symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is also less frequent if it is given earlier14. Thus, further efforts are needed not only to increase the number of ischemic stroke patients receiving thrombolytic therapy, but also to decrease the time interval between stroke onset and starting thrombolytic therapy.

Many studies show that stroke patients utilizing emergency medical service (EMS) can arrive in the ED earlier than those who do not15–20. Cooperation between EMS and hospitals shortens in-hospital management time in acute ischemic stroke patients21,22.

Importance

Nevertheless, the benefit of utilization of EMS in stroke patients might be not universal. A previous study revealed that using EMS did not make patients present to the ED earlier compared with those using other transportation modes23. In addition, although many studies show that stroke patients can arrive at ED earlier by using EMS, no study has investigated whether utilization of EMS further increases the chance that patients will arrive within the window of time for thrombolytic administration.

Goals of This Investigation

This study investigated whether utilization of EMS is associated with thrombolytic therapy administration in acute ischemic stroke patients. Because the functional outcomes of ischemic stroke patients receiving thrombolytic therapy are associated with the time interval from onset of symptoms to starting thrombolytic therapy (onset-to-needle time), we also compared the onset-to-needle time between groups who did or did not use EMS. The hypotheses are that ischemic stroke patients who present to the ED by EMS more frequently arrive within 3 hours of stroke onset, are more likely to receive thrombolytic therapy, and receive earlier thrombolytic therapy from onset of symptoms than other ischemic stroke patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This prospective observational study is based on the stroke registry at the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH), a tertiary medical center with 2450 beds in Taipei, Taiwan, which started in 1995 to investigate the risk factors, clinical course, prognosis and complications in different types of stroke, i.e., ischemic stroke, ICH, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), transient ischemic attack (TIA), and cerebral venous thrombosis. Patient who had a stroke onset within 10 days of hospital admission or during hospitalization were enrolled in the registry24,25. The diagnosis criteria followed the definition of stroke and TIA developed by the World Health Organization26. The Institutional Review Board of NTUH approved the stroke registry. For this particular study, we analyzed data of ischemic stroke patients from the registry who visited ED within 3 days of symptom onset during the study period from January 1, 2010 to July 31, 2011. If the same patient visited the ED more than once during the study period, only the first visit was included in our study.

About 300,000 residents live in the catchment area of NTUH, which included part of two cities: Taipei city and New Taipei city. EMS in the catchment area of NTUH was provided by the emergency medical technicians (EMTs) of the two cities. Both EMS systems of two cities are mixed one-tier and two-tier fire-based system27. Basic life support (BLS) teams are responsible for providing EMS to most stroke patients. The Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale is used to identify stroke patients by EMTs of the two cities. As part of standard protocol for patients with suspected stroke, EMTs check blood sugar levels and query the time of symptom onset.

Methods and Measurements

The data of NTUH stroke registry was collected by three full-time study nurses. After the patient was diagnosed as stroke or TIA according to the definition of stroke and TIA developed by the World Health Organization (WHO)26, the patient was invited to join the registry with written informed consent. If the patient was unconscious, the next of kin provided consent. Medical and other associated information of the patient was gathered prospectively with the recording form by both direct querying of patient and relatives as well as medical record review. The recording form of NTUH stroke registry adopted that of Taiwan stroke registry since 2006, which was well delineated in a previous study9. The medical information included demographics, risk factors, comorbidities, years of education, scores of National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) on ED arrival, onset time of stroke symptoms, place where stroke occurred, ED arrival time, arrival route, symptoms and signs of stroke, and the time of initiating thrombolytic therapy. Our independent variable of interest was whether the patient arrived via EMS or other transportation.

The stroke symptoms and signs of patients were then categorized into seven groups: (1) weakness of arm, leg, or face; (2) numbness of arm, leg, or face; (3) verbal problems; (4) altered mental status; (5) headache; (6) visual abnormalities; and (7) dizziness, including vertigo and problems with balance or coordination. The classification of stroke symptoms was modified from the stroke warning signs suggested by the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines4,28. Patients could have more than one symptom category assigned to them. To validate the data of the registry, we randomly sampled 10% the data to check for errors, and the error rate was only 1.7%.

In order to know the rate of ischemic stroke patients joining the stroke registry among all ischemic stroke patients, we used the medical information system in our hospital retrospectively to know the ED visiting times of the ischemic patients during the study period. If a patient visited ED during above period and had the first three ICD-9 codes of discharge diagnoses including 433.1, 434.1, 436, and 437 (indicating ischemic stroke), the admission medical records of the patient was reviewed by study nurses in order to make sure that he/she was diagnosed as new onset or recurrent ischemic stroke according to the WHO definition for stroke by the physicians with the stroke onset before ED admission and ED arrival within 3 days of symptoms onset.

Outcomes

Our main outcome was time interval between symptom onset and ED arrival (onset-to-ED time), categorized as a dichotomous variable of ≦ 3 h (early ED arrival) and > 3 h (late ED arrival). The onset time of stroke was recorded when the last time patients known to be symptom free according to statement of the patients or their families.

In order to further evaluate the effect of utilization of EMS on ischemic stroke patients arriving at ED in time, subgroup analysis for patients arriving at ED within 3 hours after symptoms onset was also performed. The endpoint of subgroup analysis was whether the patient received thrombolytic therapy. Furthermore, for patients receiving thrombolytic therapy, the geometric mean of the onset-to-needle time was also used as endpoint owing to the skewed distribution of the time data. Onset-to-needle time was defined as time interval between onset time of stroke and time of first bolus of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) given intravenously.

Statistical Analysis

The χ2 test, Student’s t-test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test and logistic regression were used for univariate analyses of variables associated with early ED arrival and receiving thrombolytic therapy. Variables with p-value < 0.2 in above univariate analyses were put into multivariate logistic analyses to determine the independent variables. We also tested whether interaction occurred between variables. We analyzed the association between EMS utilization and ED arrival ≦ 4.5 hours for sensitivity analysis, as the time window for thrombolytic administration expanded to 4.5 hours in 2012. In subgroup analysis using onset-to-needle time as the endpoint, onset-to-needle time was treated as a continuous variable, and log transformation was used to correct for skewness. A linear regression model was used for each binary variable on the natural logarithm of the onset-to-needle time and to estimate the least-squares means of the mean onset-to-needle times for both levels in each binary variable by back transformation. To examine whether the association between utilization of EMS and onset-to-needle time was mediated by other variables, we used multivariate linear regression model to adjust possible confounders. Again, the predicted mean onset-to-needle time was obtained by back-transformation through the natural logarithm of the onset-to-needle time into the geometric mean. SAS software (Version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used in statistic analysis. A two-tail P-value less than 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

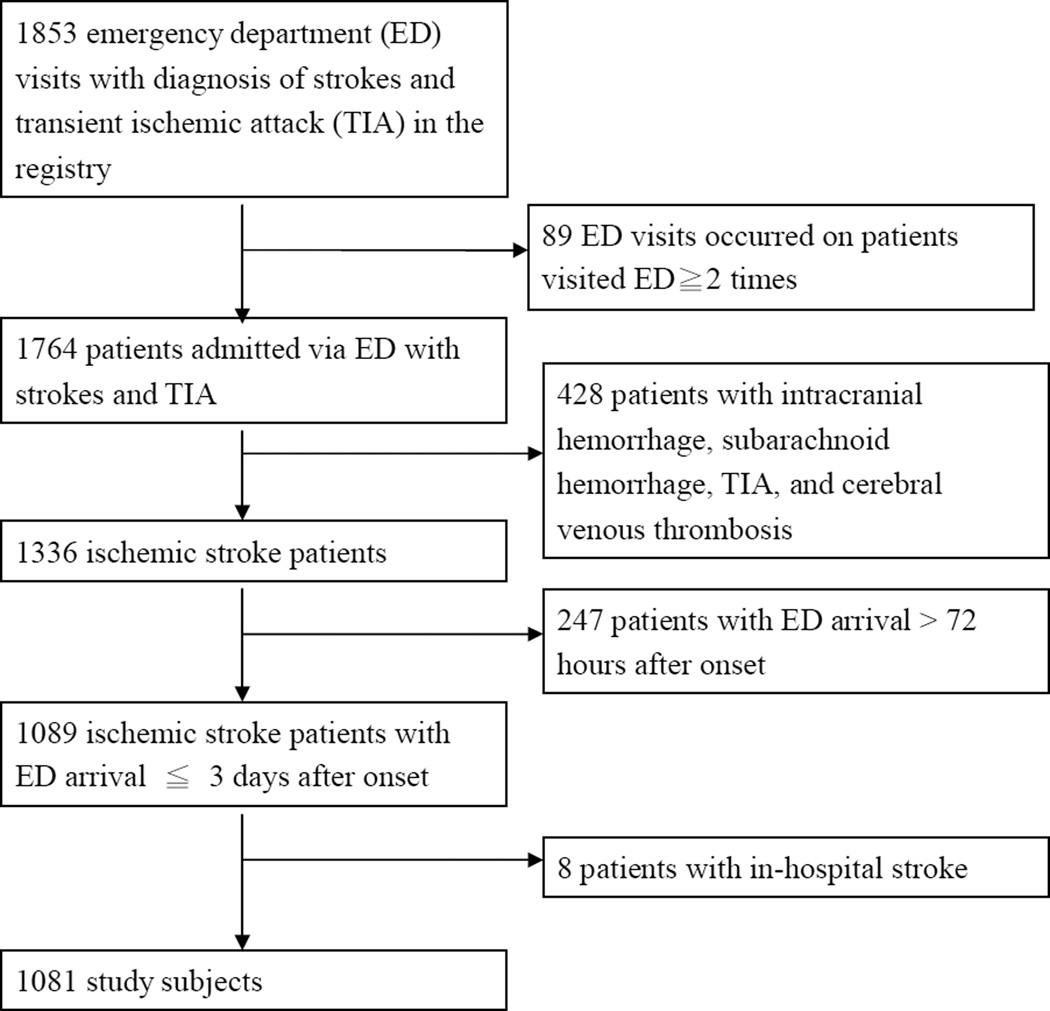

During the study period, a total of 1764 patients with 1853 ED visits were collected in the registry. Patients were excluded if they were ICH, SAH, TIA or cerebral venous thrombosis (n=428), onset-to-ED time > 72 h (n=247), and in-hospital stroke (n=8) and thus 1081 patients were included into analysis (Figure 1). The mean age was 69.6 years, and 62.3% were men. Most patients (84.4%) suffered from stroke at home. Upon arrival, patients had a median NIHSS score of 5 (range, 0–38) and GCS score of 15 (range, 3–15). The most common presenting symptoms of the patients included weakness (79.7%), verbal problems (62.6%), and numbness (55.5%). Only 289 (26.7%) patients arrived at ED within 3 h after stroke onset. Overall, 25.8% arrived by EMS, 18.9% were referred from other hospitals and outpatient clinics, 1.7% through the private ambulance, and 53.7% came by themselves.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of study subjects.

We used medical records to confirm patient capture during the study period. There were 1202 ischemic stroke patients with 1278 ED visits within 3 days after symptoms onset. Among them, 1081 (89.9%) patients joined the registry and 298 (24.8%) patients visited ED by EMS.

Main Results

The univariate analysis showed that age, years of education, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, cardiac disease, smoking, place where stroke occurred, scores of NIHSS on ED arrival, the presenting symptoms, and arrival route differed significantly between early and late ED arrival (Table 1). The multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that arrival at ED by EMS (odds ratio (OR) =3.68, 95% confidence interval (CI) =2.54–5.33), atrial fibrillation, and altered mental status were significantly associated with early ED arrival; patients with diabetes mellitus or xxx scores of NIHSS on ED arrival arrived at ED later (Table 2). There was interaction between stroke onset outside the home and arrival at ED by EMS (p=0.031). In the subgroups of patients with stroke onset outside the home and those at home, the ORs of arrival at ED by EMS in two subgroups were 17.58 (95% CI, 5.10–60.59) and 3.62 (95% CI, 2.49–5.27) (supplement 1, 2). Sensitivity analysis showed that ED arrival by EMS was still associated with ED arrival within 4.5 hours of onset (OR, 4.07; 95% CI, 2.91–5.70) (supplement 3, 4).

Table 1.

Comparison between early and late emergency department arrival of acute ischemic stroke patients (n=1081)

| Early ED arrival (n=289) |

Late ED arrival (n=792) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD | 70.7±14.1 | 69.2±12.8 | 0.109 |

| Male | 174 (60.2%) | 500 (63.1%) | 0.380 |

| Years of education | |||

| No formal education | 36 (12.5%) | 124 (15.7%) | 0.031 |

| 0–6 years | 64 (22.1%) | 200 (25.3%) | |

| 6–12 years | 96 (33.2%) | 223 (28.2%) | |

| >12 years | 86 (29.8%) | 170 (21.5%) | |

| Unknown | 7 (2.4%) | 75 (9.5%) | |

| Risk factors | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 80 (27.7%) | 299 (37.8%) | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 216 (74.7%) | 607 (76.6%) | 0.516 |

| Prior stroke | 90 (31.1%) | 236 (29.8%) | 0.670 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 112 (38.8%) | 159 (20.1%) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 27 (9.3%) | 37 (4.7%) | 0.004 |

| Cardiac disease | 41 (14.2%) | 86 (10.9%) | 0.133 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 88 (30.4%) | 238 (30.1%) | 0.899 |

| Smoking history | 93 (28.7%) | 220 (27.8%) | 0.158 |

| Place where stroke occurred | |||

| Home | 237 (82.0%) | 675 (85.2%) | 0.026 |

| Nursing home | 3 (1.0%) | 4 (0.5%) | |

| Workplace | 11 (3.8%) | 18 (2.3%) | |

| Other place except home and workplace | 35 (12.1%) | 55 (6.9%) | |

| Unknown | 3 (1.0%) | 40 (5.1%) | |

| NIHSS on ED arrival, median (IQR) | 6 (3–15) | 4 (2–9) | 0.001 |

| Presenting symptoms/signs | |||

| Weakness | 243 (84.1%) | 619 (78.2%) | 0.032 |

| Numbness | 180 (62.3%) | 420 (53.0%) | 0.007 |

| Altered mental status | 88 (30.4%) | 127 (16.0%) | <0.001 |

| Verbal problems | 188 (65.1%) | 489 (61.7%) | 0.320 |

| Headache | 11 (3.8%) | 48 (6.1%) | 0.149 |

| Visual abnormalities | 98 (33.9%) | 190 (24.0%) | 0.001 |

| Dizziness/vertigo/imbalance/incoordination | 63 (21.8%) | 228 (28.8%) | 0.022 |

| Arrival route | |||

| Emergency medical services | 147 (50.9%) | 132 (16.7%) | <0.001 |

| By patient self | 125 (43.3%) | 455 (57.4%) | |

| Transfer from other hospital | 13 (4.5%) | 141 (17.8%) | |

| Transfer from outpatient department | 3 (1.0%) | 47 (5.9%) | |

| Private ambulance | 1 (0.3%) | 17 (2.1%) |

Values are number (percentage) except age and NIHSS.

NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; ED: emergency department; IQR: interquartile range.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of variables associated with early emergency department arrival

| β | Odds ratio |

95% confidence interval |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrival route (EMS vs non-EMS) | 1.3020 | 3.68 | 2.54–5.33 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | −0.5017 | 0.61 | 0.43–0.85 | 0.004 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.5549 | 1.74 | 1.19–2.55 | 0.004 |

| NIHSS on ED arrival | −0.0327 | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 | 0.050 |

| Altered mental status | 0.5650 | 1.76 | 1.10–2.82 | 0.019 |

| Place where stroke occurred (outside vs home)* Arrival route (EMS vs non-EMS) | 1.1313 | 3.10 | 1.11–8.66 | 0.031 |

EMS: emergency medical service; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; ED: emergency department.

In the subgroup analysis, there were 289 (26.7%) patients arriving at ED within 3 hours of onset. Among them, 147 (50.87%) patients were transported by EMS and 88 (30.45%) patients received thrombolytic therapy. Of patients receiving thrombolytic therapy, 67 (76.14%) patients used EMS to hospitals. Patients who had higher likelihood of receiving thrombolytic therapy were associated with arrival at ED by EMS (OR =3.89, 95% CI =1.86–8.17), stroke onset outside the home, and higher NIHSS. Patients with longer onset-to-ED time were less likely to receive thrombolytic therapy (Table 3). There was interaction between ED arrival by EMS and stroke onset outside the home (p=0.016). The association between ED arrival by EMS and receiving thrombolytic therapy persisted in patients with stroke onset at home (supplement 5, 6). If we categorized onset to ED time as a dichotomous variable of ≦ 60 minutes and 60–180 minutes, patients with onset to ED time ≦ 60 minutes had more than twice the chance to receive thrombolytic therapy compared with patients with onset to ED time 60–180 minutes (OR, 2.53, 95% CI, 1.40–4.59) (supplement 7). The associations among ED arrival by EMS, onset-to-ED time, and receiving thrombolytic therapy were similar in patients with ED arrival within 4.5 hours of onset (supplement 8–13).

Table 3.

Variables associated with thrombolytic therapy in ischemic patients visiting emergency department within 3 hours of stroke (n=289)

| Odds ratio |

95% confidence interval |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | |||

| Age (year) | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.808 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.82 | 0.49–1.36 | 0.436 |

| Education (≧6 years vs.< 6 years) | 1.09 | 0.64–1.85 | 0.746 |

| Prior stroke | 0.97 | 0.56–1.67 | 0.911 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.09 | 1.26–3.49 | 0.005 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.16 | 0.50–2.69 | 0.733 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.05 | 0.60–1.84 | 0.854 |

| Hypertension | 1.33 | 0.74–2.42 | 0.343 |

| Smoking history | 0.84 | 0.49–1.45 | 0.526 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.87 | 0.50–1.51 | 0.618 |

| Place where stroke occurred (outside vs home) | 1.54 | 0.81–2.92 | 0.184 |

| Arrival Route (EMS vs non-EMS) | 4.83 | 2.74–8.50 | <0.001 |

| NIHSS on ED arrival | 1.09 | 1.06–1.13 | <0.001 |

| Onset to ED time | 0.98 | 0.98–0.99 | <0.001 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

| Arrival route (EMS vs non-EMS) | 3.89 | 1.86–8.17 | <0.001 |

| Place where stroke occurred (outside vs home) | 3.79 | 1.20–12.04 | 0.024 |

| NIHSS on ED arrival | 1.05 | 1.01–1.09 | 0.008 |

| Onset-to-ED time | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.006 |

| Place where stroke occurred (outside vs home)* Arrival route (EMS vs non-EMS) | 0.17 | 0.04–0.72 | 0.016 |

EMS: emergency medical service; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; ED:emergency department.

Patients who arrived at ED by EMS had a shorter onset-to-needle time than those without (supplement 14). The adjusted onset-to-needle time still demonstrated that ED arrival by EMS can decreased onset-to-needle time by 26 minutes (101.3 vs. 127.3 minutes, P=0.011) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of factors related to onset to needle time (n=88)

| Mean (minute) |

95% confidence interval (minute) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| ≦ 71 years old | 108.2 | 93.1–125.6 | 0.195 |

| > 71 years old | 119.2 | 102.7–138.4 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 113.6 | 99.1–130.2 | 0.999 |

| Female | 113.5 | 96.7–133.3 | |

| Congestive heart failure | |||

| Yes | 106.1 | 84.0–134.1 | 0.258 |

| No | 121.5 | 111.7–132.2 | |

| Arrival route | |||

| EMS | 101.3 | 89.7–114.4 | 0.011 |

| non-EMS | 127.3 | 105.7–153.2 | |

| NIHSS on ED arrival | |||

| ≦ 14 | 115.5 | 99.4–134.2 | 0.643 |

| > 14 | 111.6 | 96.3–129.4 |

EMS: emergency medical service; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; ED: emergency department.

Limitations

Our study had some limitations. First, we only captured 89.9% of patients who presented to our hospital with ischemic stroke who were evaluated in our hospital during the study time frame. We are unable to assess if there are differences in the patients captured or not captured by our study. However, because the rates of patients arriving ED by EMS are similar between study population and all ischemic stroke patients presenting to our ED, we believe that selection bias caused by including not all ED stroke patients in our study was limited.

Second, the study was conducted in a medical center situated in a metropolitan city and the results might not be extrapolated to rural EMS systems, as transportation time was not a collected variable. More studies are needed to confirm the results among these other settings. Third, the study did not evaluate patients’ knowledge and awareness about stroke and did not know the time when the patients decided to seek medical help and the reason why they chose different transportation modes and it might affect onset-to-ED time of patients. Nevertheless, after adjusting for multiple variables including onset-to-ED time, the effect of EMS utilization was still associated with receiving thrombolytic therapy in patients with stroke onset at home. During our study period, the AHA Guidelines suggest the therapeutic window of thrombolytic therapy may be extended from 3 to 4.5 hours4. Nevertheless, the associations between ED arrival by EMS and receiving thrombolytic therapy were significant in both patients groups with ED arrival within 3 hours of onset and those within 4.5 hours of onset. The extended therapeutic window did not change our results.

Discussion

There were three major findings in our study. First, our study showed that ischemic stroke patients who utilized EMS services were more likely to present earlier from onset of symptoms (within 3 h after stroke onset). Second, utilization of EMS also increased the possibility to receive thrombolytic therapy among patients arriving at ED within 3 h of stroke. Third, patients arriving at ED by EMS shortened the mean onset-to-needle time for 26 minutes. ED utilization may be the surrogate of awareness of stroke symptoms. Patients, their family or friends recognize the onset of stroke symptoms, view them as emergency, and thus they call for EMS to hospital immediately. In addition, the rapid transportation by EMS also makes patients arriving at ED earlier. Stroke occurred outside the home was found to be one of the independent factors of early ED arrival in previous studies15,29. Nevertheless, in our study, there was interaction between stroke occurring outside the home and EMS utilization. The association between EMS utilization and early ED arrival was stronger in patients with stroke onset outside the home In addition, another reason may be that the stroke symptoms of patients with stroke attack outside the home are usually recognized by non-family members, such as friends or colleagues. One study showed that non-family members deciding to seek help was one of the independent determinants of early ED arrival23.

Even among patients who arrived within 3 h of symptom onset, the use of EMS was still associated with a higher likelihood of receiving thrombolytic therapy. There may be several reasons for this. Potentially, patients who arrive via EMS may have been sicker upon arrival. The other possibility is that EMS personnel might alert the ED staffs the possible diagnosis of stroke. ED evaluation and treatment, including thrombolytic therapy, could therefore be facilitated. Besides, the prehospital notification by EMS personnel may also speed up the in-hospital process of care, and thus more patients can receive the therapy within the narrow therapeutic window.

Patients arriving at ED by EMS shortened the mean onset-to-needle time for 26 minutes in our study. The onset-to-needle time has been found to be associated not only with the functional outcome of patients with ischemic stroke but also with the incidence of the symptomatic ICH and in-hospital mortality after thrombolytic therapy administrated12–14,30. One large meta-analysis showed that, compared with patients receiving thrombolytic therapy at 180–270 minutes from stroke onset to treatment, patients receiving therapy within 90 minutes had nearly twice the odds of achieving independent functional outcomes13. In one study including 25,504 ischemic stroke patients treated with rtPA, every 15-minute reduction in door-to-needle time was associated with a 5% lower odds of mortality14. Our study result strengthens the chain of stroke survival initiated by the AHA Guideline4. Stroke patients should utilize EMS to hospitals immediately after symptoms occur.

Our study results show that increased EMS management of stroke is necessary. One previous study done in southern Taiwan showed that using EMS was not associated with earlier presentation to ED23. Nevertheless, our study had the opposite result. The difference might be explained by the improvement of patients’ awareness of acute stroke treatment, and enhanced training of the EMS system. Some previous studies also showed that utilization of EMS was associated with arrival at ED early and thus EMS utilization was recommended for acute stroke management15–20, and our study results align with these.

A large portion of patients were excluded from thrombolytic therapy due to arrival at ED beyond the treatment time7, and advocating utilization of EMS to stroke patients may alleviate this situation and thus increase the chance for stroke patients to receive thrombolytic therapy. Hospitals which are not qualified for acute stroke treatment, such as thrombolytic therapy, should refer the acute stroke patients to eligible hospitals. However, one previous report showed inter-hospital transfer may cause pre-hospital delay31. In our study, 17.8% of patients with late ED arrival were transferred from outpatient clinics or EDs of other hospitals which could not provide thrombolytic therapy. A well-trained EMS system can reduce the pre-hospital delay. When patients activate the EMS immediately when strokes are suspected, the EMTs can identify stroke patients through the prehospital stroke scale, then send the patients to the nearest appropriate hospitals with pre-hospital notification. In addition, the information about accredited stroke center should be spread to the public and the method to identify such hospitals should become part of education program of stroke because many patients arriving at ED by themselves.

Our study indicates a huge opportunity for public health awareness. Only one fourth of patients with stroke utilized EMS in our study. Furthermore, the proportion of patients arriving in the ED early in greater Taipei remained unchanged over the last decade8. In our study, 26.7% patients arrived at ED within 3 h after stroke onset compared with 27.4% in 19978. These percentages are lower as compared with other studies in Canada, Ireland, Italy and Japan7,20,32,33. More effective education programs on stroke awareness and on EMS utilization for high risk patients and their close families or friends should be developed, because most patients suffering from stroke at home and the first response in the majority of stroke patients was calling their families or friends for help instead of calling EMS34.

In addition to EMS utilization, other factors associated with higher likelihood of thrombolytic therapy in the multiple logistic regression model included higher NIHSS and shorter onset-to-ED time. If a patient arrives at ED late, the ED staff may not have enough time to finish the needed examination and to provide thrombolytic therapy in time. One study compared patients arriving at ED within 60 minutes of stroke with those arriving at 61–180 minutes35, and patients arriving within 60 minutes had more chance to receive thrombolytic therapy. Our study had similar results.

In conclusion, patients with ischemic stroke visiting ED by EMS not only arrived at ED early but also were more likely to receive thrombolytic therapy. EMS utilization can shorten onset-to-needle time, and thus may improve the functional outcome of stroke patients. The message that EMS should be called immediately if the stroke was suspected needs to be spread to the public, especially to those with high stroke risk and their close families or friends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Supports: The article was supported by NTUH research fund No.100-S1870.

Dr. Chang is supported by Award Number 1K12HL108974-01 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The Atlas of Heart Disease and Stroke. In: Mackay J, Mensah G, editors. Global burden of Stroke. Vol. 15. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim AS, Johnston SC. Global variation in the relative burden of stroke and ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2011;124:314–323. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.018820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jauch EC, Cucchiara B, Adeoye O, et al. Part 11: adult stroke: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122(18) Suppl 3:S818–S828. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group: Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hacke WH, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barber PA, Zhang J, Demchuk AM, et al. Why are stroke patients excluded from TPA therapy? An analysis of patient eligibility. Neurology. 2001;56:1015–1020. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.8.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yip PK, Jeng JS, Lu CJ, et al. Hospital arrival time after onset of different types of stroke in greater Taipei. J Formos Med Assoc. 2000;99:532–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh FI, Lien LM, Chen ST, et al. Get With the Guidelines-Stroke performance indicators: surveillance of stroke care in the Taiwan Stroke Registry: Get With the Guidelines-Stroke in Taiwan. Circulation. 2010;122:1116–1123. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.936526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeves MJ, Arora S, Broderick JP, et al. Acute stroke care in the US: results from 4 pilot prototypes of the Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry. Stroke. 2005;36:1232–1240. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000165902.18021.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heuschmann PU, Berger K, Misselwitz B, et al. Frequency of thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke and the risk of in-hospital mortality: the German Stroke Registers Study Group. Stroke. 2003;34:1106–1113. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000065198.80347.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The ATLANTIS, ECASS and NINDS rt-PA Study Group Investigators. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363:768–774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet. 2010;375:1695–1703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL, et al. Timeliness of tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy in acute ischemic stroke: patient characteristics, hospital factors, and outcomes associated with door-to-needle times within 60 minutes. Circulation. 2011;123:750–758. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.974675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salisbury HR, Banks BJ, Footitt DR, et al. Delay in presentation of patients with acute stroke to hospital in Oxford. QJM. 1998;91:635–640. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.9.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wester P, Rådberg J, Lundgren B, et al. Factors associated with delayed admission to hospital and in-hospital delays in acute stroke and TIA: a prospective, multicenter study.Seek- Medical-Attention-in-Time Study Group. Stroke. 1999;30:40–48. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derex L, Adeleine P, Nighoghossian N, et al. Factors influencing early admission in a French stroke unit. Stroke. 2002;33:153–159. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.100533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang KC, Tseng MC, Tan TY. Prehospital delay after acute stroke in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Stroke. 2004;35:700–704. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000117236.90827.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossnagel K, Jungehülsing GJ, Nolte CH, et al. Out-of-hospital delays in patients with acute stroke. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curran C, Henry C, O’Connor KA, et al. Predictors of early arrival at the emergency department in acute ischaemic stroke. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180:401–405. doi: 10.1007/s11845-011-0686-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bae HJ, Kim DH, Yoo NT, et al. Prehospital Notification from the Emergency Medical Service Reduces the Transfer and Intra-Hospital Processing Times for Acute Stroke Patients. J Clin Neurol. 2010;6:138–142. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2010.6.3.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puolakka T, Vayrynen T, Happola O, Soinne L, Kuisma M, Lindsberg PJ. Sequential analysis of pretreatment delays in stroke thrombolysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:965–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li CS, Chang KC, Tan TY, et al. The role of emergency medical services in stroke: a hospital-based study in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2005;14:126–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yip PK, Jeng JS, Lee TK, et al. Subtypes of ischemic stroke: A hospital-based stroke registry in Taiwan (SCAN-IV) Stroke. 1997;28:2507–2512. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.12.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee HY, Hwang JS, Jeng JS, et al. Quality-adjusted life expectancy (QALE) and loss of QALE for patients with ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage: a 13-year follow-up. Stroke. 2010;41:739–744. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.573543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): a major international collaboration. WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma MH, Chiang WC, Ko PC, et al. A randomized trial of compression first or analyze first strategies in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Results from an Asian community. Resuscitation. 2012;83:806–812. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleindorfer D, Lindsell CJ, Moomaw CJ, et al. Which stroke symptoms prompt a 911 call? A population-based study. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong ES, Kim SH, Kim WY, et al. Factors associated with prehospital delay in acute stroke. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:790–793. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.094425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bluhmki E, Chamorro A, Dávalos A, et al. Stroke treatment with alteplase given 3.0–4.5 h after onset of acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS III): additional outcomes and subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1095–1102. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin CS, Tsai J, Woo P, et al. Prehospital delay and emergency department management of ischemic stroke patients in Taiwan, R.O.C. Prehosp Emerg Care. 1999;3:194–200. doi: 10.1080/10903129908958936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azzimondi G, Bassein L, Fiorani L, et al. Variables associated with hospital arrival time after stroke: effect of delay on the clinical efficiency of early treatment. Stroke. 1997;28:537–542. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inatomi Y, Yonehara T, Hashimoto Y, et al. Pre-hospital delay in the use of intravenous rt-PA for acute ischemic stroke in Japan. J Neurol Sci. 2008;270:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsia AW, Castle A, Wing JJ, Edwards DF, Brown NC, Higgins TM, et al. Understanding reasons for delay in seeking acute stroke care in an underserved urban population. Stroke. 2011;42:1697–1701. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saver JL, Smith EE, Fonarow GC, et al. The "golden hour" and acute brain ischemia: presenting features and lytic therapy in >30,000 patients arriving within 60 minutes of stroke onset. Stroke. 2010;41:1431–1439. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.