Abstract

Tumor-suppressor p53 plays a key role in tumor prevention. As a transcription factor, p53 transcriptionally regulates its target genes to regulate different biological processes in response to stress, including apoptosis, cell cycle arrest or senescence, to exert its function in tumor suppression. Recent studies have revealed that metabolic regulation is a novel function of p53. Metabolic changes have been regarded as a hallmark of tumors and a key contributor to tumor development. p53 regulates many different aspects of metabolism, including glycolysis, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, pentose phosphate pathway, fatty acid synthesis and oxidation, to maintain the homeostasis of cellular metabolism, which contributes to the role of p53 in tumor suppression. p53 is frequently mutated in human tumors. In addition to loss of tumor suppressive function, tumor-associated mutant p53 proteins often gain new tumorigenic activities, termed gain-of-function of mutant p53. Recent studies have shown that mutant p53 mediates metabolic changes in tumors as a novel gain-of-function to promote tumor development. Here we review the functions and mechanisms of wild-type and mutant p53 in metabolic regulation, and discuss their potential roles in tumorigenesis.

Keywords: Tumor suppressor, p53, mutant p53, metabolism

1. Introduction

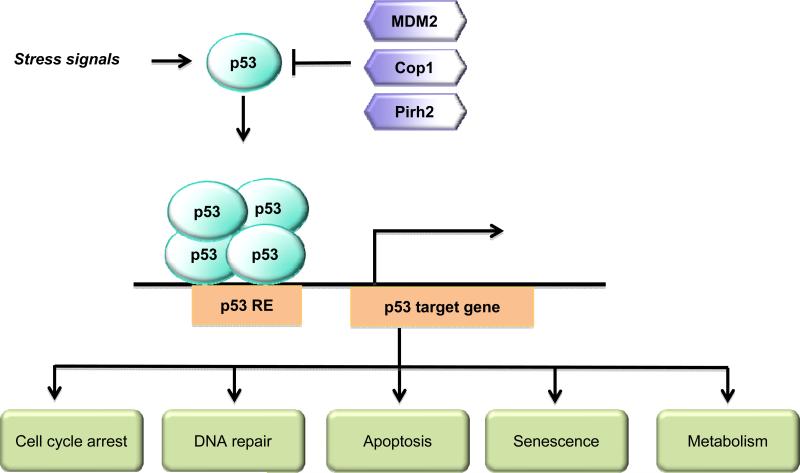

As the “guardian of the genome”, p53 plays a key role in maintaining genomic stability and tumor prevention, which has been clearly demonstrated by following evidence from both human tumors and mouse models. p53 is frequently mutated in human tumors; somatic p53 mutations occur in almost every type of human tumors and in over 50% of all tumors [1-3]. In those tumors with low p53 mutation rates, p53 is often inactivated by alternative mechanisms. For instance, p53 can be inactivated and degraded by human papillomavirus E6 protein (HPV-E6) in cervical cancer which has a low p53 mutation rate [4, 5]. The germline p53 mutations in human beings cause a hereditary cancer predisposition syndrome, Li–Fraumeni syndrome, which leads to the development of various types of tumors in 50% of the patients by the age of 30 and 90% of patients by the age of 60 [6]. Similarly, p53 knockout mice are extremely prone to tumor development; most p53−/− mice develop tumors (principally lymphomas and sarcomas) within 6 months of age, and p53+/− mice develop tumors within one year of age [7, 8]. As a transcription factor, p53 mainly exerts its tumor suppressive function through transcriptional regulation of its target genes. In normal unstressed cells, p53 protein is kept at a low level by its negative regulators, such as Mdm2, COP1 and Pirh2, which are E3 ubiquitin ligases for p53 and degrade p53 through the proteasome degradation pathway [9, 10]. In response to a variety of stress signals arising from both intracellular and extracellular environments, including DNA damage, nutrient deprivation, hypoxia and oncogene activation, p53 protein is stabilized mainly through post-translational modifications, which leads to p53 protein activation and accumulation in cells [1, 11, 12]. Once activated, p53 binds to a specific degenerative DNA sequence, termed the p53-responsive element (p53 RE), in its target genes to regulate the expression of these genes [12, 13]. Depending on the cell and tissue types, the type and intensity of stress signals, through the regulation of a group of its target genes, p53 selectively regulates cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, apoptosis, or senescence to maintain genomic integrity and prevent tumor formation. For instance, in response to mild or transient stress signals, p53 induces its target genes involved in cell cycle arrest (e.g. p21, Gadd45, and 14-3-3 ) and DNA repair (e.g. p48, and p53R2) to allow cells to survive until the damage has been repaired or stress has been removed [11, 12, 14]. In response to severe or sustained stress signals, p53 usually induces genes involved in apoptosis (e.g. Puma, Bax, Fas, PIG3, and Killer/DR5) and senescence (e.g. p21), and therefore, prevents the accumulation of damaged cells [11, 12, 14] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Tumor suppressor p53 and its signaling pathway. In unstressed cells, p53 protein is kept at a low level by different negative regulators, including E3 ubiquitin ligases MDM2, Cop1 and Pirh2. In response to a wild variety of stress signals, p53 is activated and accumulated in cells. The activated p53 then binds to p53 responsive elements (p53 REs) in its target genes to transcriptionally regulate their expression, which in turn regulates various biological processes, including cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, apoptosis, senescence and metabolism.

Metabolic changes are a hallmark of tumor cells, which has been recently regarded as a key contributor to tumor progression [15-17]. The rapid growth and division of tumor cells requires energy and precursors for macromolecule biosynthesis. To meet the energetic and biosynthetic demands, tumor cells often display fundamental changes in metabolism. Interestingly, recent studies have revealed a novel function of p53 in regulation of metabolism, including the regulation of glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and lipid metabolism, which contributes to the role of p53 in tumor suppression. In this review, we present an overview of the function and mechanism of p53 in regulating metabolism, as well as the gain-of-function oncogenic activity of mutant p53 in mediating metabolic changes in tumors.

2. p53 regulates metabolism

2.1. p53 and glycolysis

The Warburg effect is the most remarkable and best characterized metabolic change in tumor cells. Unlike majority of normal cells which depend on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to provide energy, most tumor cells primarily utilize glycolysis for their energy needs even in the presence of sufficient oxygen, a phenomenon termed aerobic glycolysis or the Warburg effect [18]. Although glycolysis is much less efficient in producing energy compared with mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis can produce ATP in greater quantities and at a faster rate when glucose is in excess [19]. In addition to providing quick energy in large quantities, glycolysis also generates metabolic intermediates to provide precursors for macromolecule biosynthesis, which are crucial for the rapid growth and division of tumor cells. Recent studies have shown that the activation of oncogenes such as MYC, AKT, HIF-1α in tumor cells can stimulate glycolysis by increasing the expression of glucose transporters (GLUTs) and/or glycolytic enzymes [15-17].

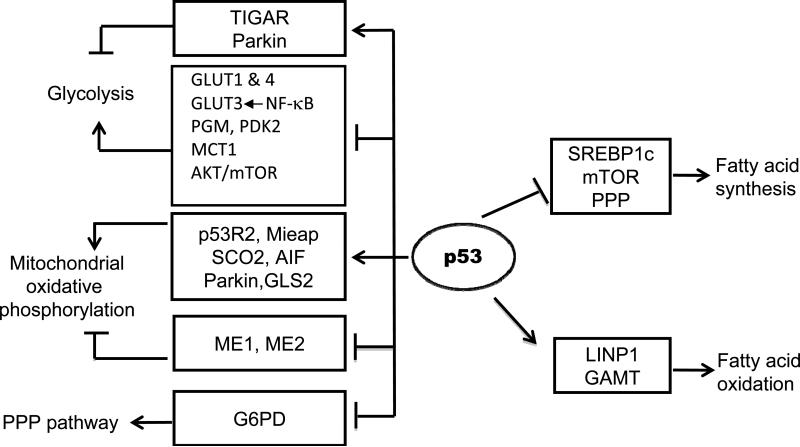

p53 has been shown to repress glycolysis through multiple mechanisms. Transport of glucose across the plasma membrane of cells is the first rate-limiting step for glucose metabolism, which is mediated by GLUT 1-4. p53 transcriptionally represses the expression of the GLUT1 and GLUT4 to decrease glucose uptake in cells [20]. p53 induces the expression of TIGAR (TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator), which decreases the intracellular concentrations of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, and thus reduces glycolysis and diverts glucose catabolism to the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) [21]. p53 down-regulates the protein levels of PGM (phosphoglycerate mutase), a glycolytic enzyme, and inhibits glycolysis [22]. However, the mechanism by which p53 down-regulates the PGM protein levels is unclear. p53 decreases the expression of PDK2 (pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 2), which inactivates the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex that converts pyruvate to acetyl-CoA and inhibits lactate production [23]. p53 induces the expression of Parkin (PARK2) to negatively regulate glycolysis [24]. Parkin was initially identified as a gene associated with neurodegenerative Parkinson disease, and was recently shown to be a potential tumor suppressor. The mechanism by which Parkin negatively regulates glycolysis is still unclear. p53 decreases the expression of MCT1 (monocarboxylate transporter 1) to inhibit lactate export produced by elevated glycolytic flux, and thereby prevents facilitation of the shift from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to the glycolytic pathway [25] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The regulation of cellular metabolism by p53. p53 regulates glycolysis, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and lipid metabolism in cells. p53 represses glycolysis through inducing the expression of TIGAR and Parkin and repressing the expression of GLUT1 & 4, PGM, PDK2, and MCT1. Furthermore, p53 negatively regulates the AKT/mTOR signaling to repress glycolysis, and negatively regulates the NF-κB signaling to repress the expression of GLUT3. p53 transcriptionally induces SCO2, AIF, p53R2, Mieap, Parkin and GLS2, and represses the expression of ME1 and ME2 to promote mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. p53 physically interacts with G6PD and inhibits its activity to negatively regulate the PPP pathway. p53 induces the expression of LPIN1 and GAMT to enhance fatty acid oxidation, and represses the expression of SREBP1c to inhibit fatty acid synthesis. In addition, p53 negatively regulates fatty acid synthesis through inhibition of the mTOR and PPP pathways.

In addition to directly regulating the expression of above-mentioned genes and/or proteins involved in glycolysis, p53 also negatively regulates the AKT/mTOR and NF-κB signaling pathways to repress glycolysis. The AKT/mTOR and NF-κB signaling pathways are frequently activated in various types of tumors and can promote glycolysis in tumors [15, 16]. p53 induces the expression of IGF-BP3 and PTEN to negatively regulate the AKT signaling, and induces the expression of AMPK-β, TSC2, Sestrin 1 & 2, and REDD1 to negatively regulate the mTOR signaling [26]. Furthermore, p53 reduces the activity of NF-κB signaling by inhibiting the activities of IκB kinase α and β, which in turn reduces the expression of GLUT3 to repress glucose uptake and glycolysis [27].

2.2. p53 and the pentose phosphate pathway

The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) is an alternative pathway to glycolysis. The PPP has two phases, including an oxidative phase which produces NADPH, an important intracellular reductant required for reductive biosynthesis, and a nonoxidative phase which produces ribose-5-phosphate, the precursor for biosynthesis of nucleotides [28]. Metabolites from glycolysis can be shunted into the PPP and used for the production of NADPH and ribose- 5-phosphate [28]. The PPP is frequently activated in tumors through different mechanisms. The overexpression of PKM2 (pyruvate kinase M2) in various types of tumors has been reported to activate the PPP [29, 30]. PKM2 is the enzyme that catalyzes phosphoenolpyruvate to pyruvate as the final step of glycolysis. PKM2 exists in an active tetrameric form in differentiated tissues and most normal proliferating cells, but in an inactive dimeric form in most tumors [29, 30]. Therefore, the overexpression of the inactive dimeric form of PKM2 in tumor cells slows glycolysis and leads to the build up of metabolic intermediates, and thereby promotes the shuttling of these substrates through the PPP [29, 30]. The G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) is the first and rate-limiting enzyme of the PPP. p53 was reported to directly bind to G6PD and inhibit its activity, thereby inhibiting the diversion of glycolytic intermediates into the PPP [31]. Through the negative regulation of the PPP, p53 can reduce the production of NADPH and ribose-5-phosphate which are critical to support tumor cell growth and division (Fig. 2).

2.3. p53 and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation

In addition to repressing the glycolysis and PPP, p53 also plays an important role in maintaining mitochondrial integrity and enhancing mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. p53 regulates copy number of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and mitochondrial biogenesis via the induction of the expression of p53R2 (p53-controlled ribonucleotide reductase) [32-34]. Furthermore, p53 maintains mitochondrial genetic integrity through its interaction with mtDNA polymerase γ, which enhances DNA replication function of polymerase γ and therefore mitochondrial function in response to intracellular and extracellular stress signals that induce mtDNA damage, including reactive oxygen species [35]. p53 also induces the expression of Mieap, a protein involved in the repair or degradation of unhealthy mitochondria in response to mitochondrial damage. Through the regulation of Mieap, p53 promotes the repair or elimination of damaged mitochondria, thereby controlling mitochondrial quality [36]. p53 up-regulates the expression of SCO2 (Synthesis of Cytochrome c Oxidase 2), which plays an important role in the assembly of mitochondrial complex IV in the electron transport chain [37]. Furthermore, p53 induces the expression of AIF (apoptosis-inducing factor), which is required for efficient mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, most likely through its role in ensuring the proper assembly and function of mitochondrial respiratory complex I [38]. In addition to inhibition of glycolysis, the induction of Parkin by p53 also enhances mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Parkin up-regulates the protein levels of PDHA1 (pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 1), which is a critical component of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex that catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate into acetyl-CoA for tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle [24]. p53 also induces the expression of GLS2 (mitochondrial glutaminase 2), which catalyzes the hydrolysis of glutamine to glutamate [39, 40]. Glutamate can be further converted into α-ketoglutarate, an important substrate for TCA. By increasing the levels of α-ketoglutarate, GLS2 promotes TCA cycle and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Furthermore, p53 negatively regulates the expression of malic enzymes ME1 and ME2, enzymes involved in the TCA cycle which recycle malate to pyruvate and provide TCA cycle intermediates for biosynthesis and NADPH production [41]. Therefore, through the inhibition of ME1 and ME2, p53 reduces the utilization of TCA cycle intermediates for biosynthesis and NADPH production to inhibit tumor cell proliferation (Fig. 2).

2.4. p53 and lipid metabolism

Fatty acids are the major group of lipids that are metabolized in cells. Fatty acids play important roles in energy storage, phospholipid membrane formation and signaling transduction. When metabolized, fatty acids yield large quantities of ATP through fatty acid β-oxidation in mitochondria. Fatty acid synthesis and fatty acid oxidation are the major aspects of lipid metabolism in cells to maintain the balance of fatty acid metabolism. Cancer cells frequently display an increased rate of fatty acid synthesis, which can generate building blocks for the formation of new phospholipid membrane to support the rapid growth and division of tumor cells [42-44]. The activation and/or overexpression of FASN (fatty acid synthase) and ACLY (ATP citrate lyase), two lipogeneic enzymes is the main cause for increased fatty acid synthesis in various types of tumors [42-44]. Inhibition of FASN and ACLY has been reported to inhibit cell transformation and tumorigenesis, suggesting the important role of fatty acid synthesis in tumor development [45, 46]. On the other hand, enhanced fatty acid oxidation can inhibit glycolysis and may contribute to tumor suppression [47].

Recent studies have shown that p53 plays an important role in regulation of lipid metabolism, including enhancing fatty acid oxidation and inhibiting fatty acid synthesis. For example, p53 can induce the expression of Lipin1 and GAMT (Guanidinoacetate methyltransferase) to enhance fatty acid oxidation [48, 49]. Lipin1 is a nuclear transcriptional coactivator that induces the expression of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation through interaction with transcription factors PPARα and PGC-1α. Lipin1 is induced by p53 in response to glucose starvation, which in turn leads to the activation of fatty acid oxidation in cells. GAMT is a critical enzyme that synthesizes creatine. In response to glucose starvation, GAMT can be induced by p53 activation, which in turn up-regulates fatty acid oxidation, although the mechanism is unclear. In addition to enhancing fatty acid oxidation, p53 also represses fatty acid synthesis. Transcription factor SREBP1c (sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c) activates the expression of fatty acid synthesis enzymes, including FASN and ACLY. p53 has been reported to repress the expression of SREBP1c, and therefore reduces the expression of its target genes FASN and ACLY [50]. The mTOR pathway and the PPP, two pathways frequently activated in tumors, promote fatty acid synthesis [28, 51]. p53 has been reported to negatively regulate these two pathways [26, 31], which contributes to the function of p53 in repressing fatty acid synthesis (Fig. 2).

2.5. p53 and autophagy

Autophagy is a membrane trafficking process that delivers cytoplasmic constituents, such as damaged proteins and organelles, to the lysosome for degradation. In the presence of sufficient external nutrients, autophagy acts as a homeostatic mechanism to maintain the integrity of protein and organelles in most situations. Under the condition of nutritional deprivation, autophagy can be activated to provide ATP from internal sources for cell survival. Recent studies have suggested that autophagy contributes to maintaining genomic stability and tumor prevention in normal cells and tissues, whereas autophagy may promote tumor cell survival and tumor progression in tumor cells and tissues [52]. p53 has been reported to regulate autophagy in a context dependent manner. p53 promotes autophagy through inducing the expression of several genes involved in autophagy, including DRAM, PUMA, Bax, ISG20L1 and Ei24 [53-55]. p53 can also promote autophagy through negative regulation of the mTOR signaling pathway [56]. Interestingly, p53 was also reported to inhibit autophagy under some circumstances. For example, cytoplasmic p53 was reported to inhibit autophagy without activation of p53 target genes in some cell lines [57]. Similarly, tumor associated-mutant p53 proteins also inhibit autophagy, especially for these mutant p53 proteins localized in the cytoplasm [58]. However, it is unclear whether cytoplasmic p53 (wild type) and mutant p53 inhibit autophagy through different mechanisms. Clearly, more studies are required to elucidate the detailed mechanisms how p53 promotes or inhibits autophagy in a context dependent manner, and how the regulation of autophagy contributes to p53's role in tumor suppression.

3. p53 in metabolic regulation and tumor suppression

With the recent identification of more and more functions of p53, an interesting question has been raised about which functions are critical for the p53's role in tumor suppression. It has been widely accepted that the functions of p53 in regulating apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and senescence contribute mainly to the tumor suppressive activity of p53. However, this concept is challenged by some recent studies in animal models. For example, whereas p21 plays a critical role in mediating p53-dependent cell cycle arrest and senescence, unlike p53 knockout mice, p21 knockout mice are not prone to early-onset tumorigenesis, suggesting that the functions of p53 in inducing cell cycle arrest and senescence do not contribute significantly to tumor suppression [59]. The PUMA knockout mice are not as tumor prone as p53 knockout mice, suggesting that p53-mediated apoptosis is dispensable for the tumor suppression function of p53 [60]. In a KrasG12D-driven transgenic model of non-small cell lung cancer, mice with mutations in p53's first transactivation domain (L25Q, W26S), which are deficient for cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis but not senescence, do not display accelerated tumor formation [61]. A recent study showed that mice with knockout of p21, Puma and Noxa (p21−/− puma−/− noxa−/−), which are deficient for p53-mediated apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and senescence, are resistant to early-onset tumor development [62]. Consistently, whereas mice expressing the p53 mutations in three acetylation sites (K117R+K161R+K162R) displayed impaired functions of p53-mediated apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and senescence, these mice are not prone to early-onset tumorigenesis, suggesting these functions of p53 are dispensable for p53-mediated suppression of tumor development. Interestingly, in these mice p53 retains the ability to regulate metabolism, including inducing the expression of GLS2 and TIGAR, and repressing glucose uptake and glycolysis, suggesting that the regulation of energy metabolism by p53 could play a more crucial role in p53's tumor suppression [63]. Whereas it is still unclear which functions are critical for the p53's role in tumor suppression, considering the critical role of metabolic changes in tumorigenesis as demonstrated by many recent studies, p53's function in regulating many different aspects of metabolism very likely contributes greatly to the role of p53 in tumor suppression.

4. Mutant p53 gain-of-function in metabolism

p53 is the most-frequently mutated gene in human tumors. Unlike many other tumor suppressors (e.g. RB, APC, and VHL), which are frequently inactivated by deletion or truncation mutations in tumors, majority of p53 mutations are missense mutations, which usually lead to the production of the full-length mutant protein [3]. It has been well-documented that some tumor-associated mutant p53 proteins not only lose the tumor suppressive function of wild-type p53, but also gain new oncogenic functions that are independent of wild-type p53, referred as the gain-of-function of mutant p53 [64-66]. Many different gain-of-function activities of mutant p53 have been identified, including promoting cell proliferation, angiogenesis, migration, invasion, metastasis, and chemoresistance [64-66]. The gain-of-function of mutant p53 has been clearly demonstrated in vitro by ectopic expression of mutant p53 in p53-null tumor cells or knockdown of endogenous mutant p53 in tumor cells that have lost the wild-type p53 allele. Recent studies in mutant p53 knock-in mouse models have clearly demonstrated the mutant p53 gain-of-function in vivo; mice expressing R172H or R270H mutant p53, which are equivalent to two human tumor mutational “hotspots” R175H and R273H, respectively, develop an altered spectrum of tumors and more metastatic tumors compared with p53−/− mice [67, 68]. The mutant p53 gain-of-function hypothesis was further supported by the evidence from Li–Fraumeni syndrome patients showing that germline missense mutations in p53 is associated with an earlier age of onset for tumors (~9 years) compared with germline deletions in p53 [69].

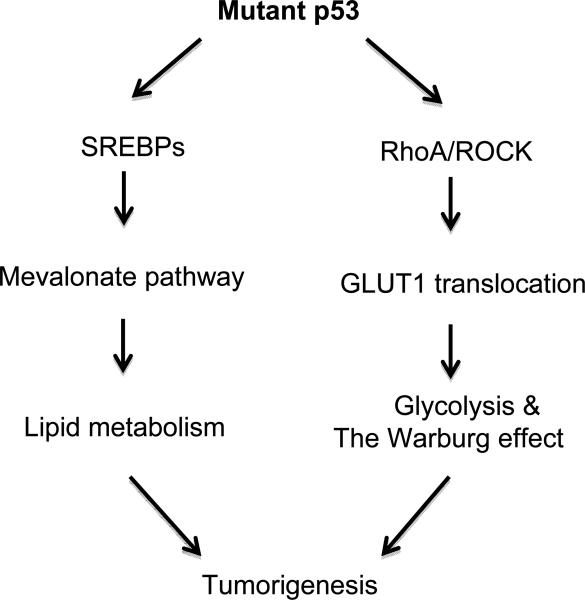

Recently, tumor-associated mutant p53 was reported to promote tumor metabolic changes as a novel gain-of-function in promoting tumor development. For instance, mutant p53 promotes tumor lipid metabolism. Mutant p53 binds and activates transcription factor SREBPs, and induces the expression of many genes in the mevalonate pathway, a pathway that regulates lipid metabolism, including cholesterol and isoprenoid synthesis [70]. The activation of the mevalonate pathway has been implicated in multiple aspects of tumorigenesis, including proliferation, survival, invasion, and metastasis [71, 72]. The activation of the mevalonate pathway by mutant p53 leads to the disruption of breast tissue architecture in 3D cell cultures, contributing to the mutant p53 gain-of-function in promoting breast tumorigenesis [70]. Furthermore, mutant p53 induces the expression of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis, such as FASN. Inhibition of the mevalonate pathway greatly compromises the effect of mutant p53 on breast tissue architecture [70]. A recent study further showed that mutant p53 promotes glycolysis and the Warburg effect in both cultured cells and mutant p53 R172H knock-in mice as an additional novel gain-of-function of mutant p53 [73]. This gain-of-function activity of mutant p53 is mainly achieved through the activation of RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway, which in turn promotes the translocation of GLUT1 to the plasma membrane, and therefore, promotes glucose uptake in tumor cells. Furthermore, repressing glycolysis in tumor cells by inhibition of RhoA/ROCK/GLUT1 signaling greatly compromises mutant p53 gain-of-function in promoting tumor growth in mouse models [73] (Fig. 3). In addition, mutant p53 was reported to induce the expression of glycolytic enzyme hexokinase II, which could promote glycolysis [74]. Melanoma cells containing R175H mutant p53 can utilize exogenous pyruvate to promote survival under the condition of glucose depletion [75]. These findings together demonstrated an important role of mutant p53 in mediating cancer metabolic changes in cancer, providing a new mechanism underlying mutant p53 gain-of-function in tumorigenesis.

Fig. 3.

The regulation of metabolism by gain-of-function mutant p53. Tumor- associated mutant p53 binds and activates SREBPs, which induce the expression of many genes in the mevalonate pathway, a pathway that regulates lipid metabolism. Furthermore, mutant p53 activates the RhoA/ROCK signaling, which in turn stimulates the translocation of GLUT1 to the plasma membrane, and thereby promotes glycolysis and the Warburg effect in tumor cells. The activation of the mevalonate pathway and glycolysis by mutant p53 contributes to the role of mutant p53 in tumorigenesis.

5. Conclusions and future directions

p53 has been extensively studied since its discovery in 1979. Many functions of p53, such as cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence has been discovered and studied for decades [2]. Despite this intensive effort and massive amount of knowledge that has accumulated about p53, we are only beginning to see the complexity of p53. In the case of metabolism, only recently we started to appreciate the contribution of p53 to metabolic regulation. Many questions remain. For example, it is still unclear how the function of p53 in metabolism contributes to p53's role in tumor suppression and other aspects of diseases, such as diabetes and aging. It has been known that the p53 activation and regulation of its target genes appear to be tissue, cell type and stress specific. It is still not well-understood how p53 regulates different aspects of metabolism in different types of cells and tissues, as well as in response to different stress signals, including glucose starvation, nutritional deprivation, DNA damage, oncogene activation, etc. Interestingly, it has been reported that mutant p53 proteins and wild-type p53 proteins often regulate same cellular biological processes with opposite effects. For example, in metabolic regulation, wild type p53 inhibits glycolysis while mutant p53 promotes glycolysis through distinct mechanisms [73]. While wild-type p53 can regulate many other aspects of metabolism, currently, the role of mutant p53 in regulation of tumor metabolism remains largely unknown. Furthermore, it is unclear how different forms of mutant p53 impact differently upon tumor metabolism. The metabolic regulation by p53 remains a highly dynamic and rapidly expanding area of p53 study. Future studies will significantly increase our understanding of the functions and mechanisms of p53 and its mutants in metabolic regulation and their influences upon tumor and other diseases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01CA143204) and CINJ Foundation (to Z.F.), and by grants from NIH (R01CA160558-01) (to W.H.). J. L. was supported by the NJCCR postdoctoral fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

References

- 1.Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine AJ, Oren M. The first 30 years of p53: growing ever more complex. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:749–758. doi: 10.1038/nrc2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olivier M, Hussain SP, Caron de Fromentel C, Hainaut P, Harris CC. TP53 mutation spectra and load: a tool for generating hypotheses on the etiology of cancer. IARC scientific publications. 2004:247–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tommasino M, Accardi R, Caldeira S, Dong W, Malanchi I, Smet A, Zehbe I. The role of TP53 in Cervical carcinogenesis. Human mutation. 2003;21:307–312. doi: 10.1002/humu.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheffner M, Werness BA, Huibregtse JM, Levine AJ, Howley PM. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell. 1990;63:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strong LC. General keynote: hereditary cancer: lessons from Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Gynecologic oncology. 2003;88:S4–7. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6673. discussion S11-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA, Jr., Butel JS, Bradley A. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT, Weinberg RA. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris SL, Levine AJ. The p53 pathway: positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene. 2005;24:2899–2908. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks CL, Gu W. p53 ubiquitination: Mdm2 and beyond. Mol Cell. 2006;21:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine AJ, Hu W, Feng Z. The P53 pathway: what questions remain to be explored? Cell death and differentiation. 2006;13:1027–1036. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riley T, Sontag E, Chen P, Levine A. Transcriptional control of human p53- regulated genes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:402–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.el-Deiry WS, Kern SE, Pietenpol JA, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Definition of a consensus binding site for p53. Nat Genet. 1992;1:45–49. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vousden KH, Ryan KM. p53 and metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:691–700. doi: 10.1038/nrc2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guppy M, Greiner E, Brand K. The role of the Crabtree effect and an endogenous fuel in the energy metabolism of resting and proliferating thymocytes. Eur J Biochem. 1993;212:95–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartzenberg-Bar-Yoseph F, Armoni M, Karnieli E. The tumor suppressor p53 down-regulates glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT4 gene expression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2627–2633. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak MA, Vidal MN, Nakano K, Bartrons R, Gottlieb E, Vousden KH. TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondoh H, Lleonart ME, Gil J, Wang J, Degan P, Peters G, Martinez D, Carnero A, Beach D. Glycolytic enzymes can modulate cellular life span. Cancer Res. 2005;65:177–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Contractor T, Harris CR. p53 negatively regulates transcription of the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase Pdk2. Cancer Res. 2012;72:560–567. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang C, Lin M, Wu R, Wang X, Yang B, Levine AJ, Hu W, Feng Z. Parkin, a p53 target gene, mediates the role of p53 in glucose metabolism and the Warburg effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16259–16264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113884108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boidot R, Vegran F, Meulle A, Le Breton A, Dessy C, Sonveaux P, Lizard- Nacol S, Feron O. Regulation of monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 expression by p53 mediates inward and outward lactate fluxes in tumors. Cancer Res. 2012;72:939–948. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng Z, Levine AJ. The regulation of energy metabolism and the IGF-1/mTOR pathways by the p53 protein. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawauchi K, Araki K, Tobiume K, Tanaka N. p53 regulates glucose metabolism through an IKK-NF-kappaB pathway and inhibits cell transformation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:611–618. doi: 10.1038/ncb1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wamelink MM, Struys EA, Jakobs C. The biochemistry, metabolism and inherited defects of the pentose phosphate pathway: a review. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 2008;31:703–717. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-1015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris I, McCracken S, Mak TW. PKM2: a gatekeeper between growth and survival. Cell Res. 2012;22:447–449. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo W, Semenza GL. Emerging roles of PKM2 in cell metabolism and cancer progression. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23:560–566. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang P, Du W, Wang X, Mancuso A, Gao X, Wu M, Yang X. p53 regulates biosynthesis through direct inactivation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:310–316. doi: 10.1038/ncb2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bourdon A, Minai L, Serre V, Jais JP, Sarzi E, Aubert S, Chretien D, de Lonlay P, Paquis-Flucklinger V, Arakawa H, Nakamura Y, Munnich A, Rotig A. Mutation of RRM2B, encoding p53-controlled ribonucleotide reductase (p53R2), causes severe mitochondrial DNA depletion. Nat Genet. 2007;39:776–780. doi: 10.1038/ng2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulawiec M, Ayyasamy V, Singh KK. p53 regulates mtDNA copy number and mitocheckpoint pathway. J Carcinog. 2009;8:8. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.50893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lebedeva MA, Eaton JS, Shadel GS. Loss of p53 causes mitochondrial DNA depletion and altered mitochondrial reactive oxygen species homeostasis. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1787:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Achanta G, Sasaki R, Feng L, Carew JS, Lu W, Pelicano H, Keating MJ, Huang P. Novel role of p53 in maintaining mitochondrial genetic stability through interaction with DNA Pol gamma. EMBO J. 2005;24:3482–3492. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitamura N, Nakamura Y, Miyamoto Y, Miyamoto T, Kabu K, Yoshida M, Futamura M, Ichinose S, Arakawa H. Mieap, a p53-inducible protein, controls mitochondrial quality by repairing or eliminating unhealthy mitochondria. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matoba S, Kang JG, Patino WD, Wragg A, Boehm M, Gavrilova O, Hurley PJ, Bunz F, Hwang PM. p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science. 2006;312:1650–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1126863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stambolsky P, Weisz L, Shats I, Klein Y, Goldfinger N, Oren M, Rotter V. Regulation of AIF expression by p53, Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:2140–2149. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu W, Zhang C, Wu R, Sun Y, Levine A, Feng Z. Glutaminase 2, a novel p53 target gene regulating energy metabolism and antioxidant function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7455–7460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001006107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki S, Tanaka T, Poyurovsky MV, Nagano H, Mayama T, Ohkubo S, Lokshin M, Hosokawa H, Nakayama T, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Sato E, Nagao T, Yokote K, Tatsuno I, Prives C. Phosphate-activated glutaminase (GLS2), a p53- inducible regulator of glutamine metabolism and reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7461–7466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002459107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang P, Du W, Mancuso A, Wellen KE, Yang X. Reciprocal regulation of p53 and malic enzymes modulates metabolism and senescence. Nature. 2013;493:689–693. doi: 10.1038/nature11776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mashima T, Seimiya H, Tsuruo T. De novo fatty-acid synthesis and related pathways as molecular targets for cancer therapy. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1369–1372. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santos CR, Schulze A. Lipid metabolism in cancer. FEBS J. 2012;279:2610–2623. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuhajda FP, Jenner K, Wood FD, Hennigar RA, Jacobs LB, Dick JD, Pasternack GR. Fatty acid synthesis: a potential selective target for antineoplastic therapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91:6379–6383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hatzivassiliou G, Zhao F, Bauer DE, Andreadis C, Shaw AN, Dhanak D, Hingorani SR, Tuveson DA, Thompson CB. ATP citrate lyase inhibition can suppress tumor cell growth. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuhajda FP, Pizer ES, Li JN, Mani NS, Frehywot GL, Townsend CA. Synthesis and antitumor activity of an inhibitor of fatty acid synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3450–3454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050582897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldstein I, Rotter V. Regulation of lipid metabolism by p53 - fighting two villains with one sword. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2012;23:567–575. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu Y, Prives C. p53 and Metabolism: The GAMT Connection. Mol Cell. 2009;36:351–352. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Assaily W, Rubinger DA, Wheaton K, Lin Y, Ma W, Xuan W, Brown- Endres L, Tsuchihara K, Mak TW, Benchimol S. ROS-mediated p53 induction of Lpin1 regulates fatty acid oxidation in response to nutritional stress. Molecular cell. 2011;44:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yahagi N, Shimano H, Matsuzaka T, Najima Y, Sekiya M, Nakagawa Y, Ide T, Tomita S, Okazaki H, Tamura Y, Iizuka Y, Ohashi K, Gotoda T, Nagai R, Kimura S, Ishibashi S, Osuga J, Yamada N. p53 Activation in adipocytes of obese mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25395–25400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soliman GA. The integral role of mTOR in lipid metabolism. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:861–862. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.6.14930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kimmelman AC. The dynamic nature of autophagy in cancer. Genes & development. 2011;25:1999–2010. doi: 10.1101/gad.17558811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crighton D, Wilkinson S, O'Prey J, Syed N, Smith P, Harrison PR, Gasco M, Garrone O, Crook T, Ryan KM. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Morselli E, Kepp O, Malik SA, Kroemer G. Autophagy regulation by p53. Current opinion in cell biology. 2010;22:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao YG, Zhao H, Miao L, Wang L, Sun F, Zhang H. The p53-induced gene Ei24 is an essential component of the basal autophagy pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:42053–42063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.415968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng Z, Zhang H, Levine AJ, Jin S. The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8204–8209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502857102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Djavaheri-Mergny M, D'Amelio M, Criollo A, Morselli E, Zhu C, Harper F, Nannmark U, Samara C, Pinton P, Vicencio JM, Carnuccio R, Moll UM, Madeo F, Paterlini-Brechot P, Rizzuto R, Szabadkai G, Pierron G, Blomgren K, Tavernarakis N, Codogno P, Cecconi F, Kroemer G. Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53. Nature cell biology. 2008;10:676–687. doi: 10.1038/ncb1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morselli E, Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Criollo A, Vicencio JM, Soussi T, Kroemer G. Mutant p53 protein localized in the cytoplasm inhibits autophagy. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3056–3061. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.19.6751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deng C, Zhang P, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Leder P. Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell. 1995;82:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Michalak EM, Villunger A, Adams JM, Strasser A. In several cell types tumour suppressor p53 induces apoptosis largely via Puma but Noxa can contribute. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1019–1029. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brady CA, Jiang D, Mello SS, Johnson TM, Jarvis LA, Kozak MM, Kenzelmann Broz D, Basak S, Park EJ, McLaughlin ME, Karnezis AN, Attardi LD. Distinct p53 transcriptional programs dictate acute DNA-damage responses and tumor suppression. Cell. 2011;145:571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valente LJ, Gray DH, Michalak EM, Pinon-Hofbauer J, Egle A, Scott CL, Janic A, Strasser A. p53 efficiently suppresses tumor development in the complete absence of its cell-cycle inhibitory and proapoptotic effectors p21, Puma, and Noxa. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li T, Kon N, Jiang L, Tan M, Ludwig T, Zhao Y, Baer R, Gu W. Tumor suppression in the absence of p53-mediated cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence. Cell. 2012;149:1269–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oren M, Rotter V. Mutant p53 gain-of-function in cancer. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2010;2:a001107. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Muller PA, Vousden KH. p53 mutations in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:2–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Freed-Pastor WA, Prives C. Mutant p53: one name, many proteins. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1268–1286. doi: 10.1101/gad.190678.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lang GA, Iwakuma T, Suh YA, Liu G, Rao VA, Parant JM, Valentin-Vega YA, Terzian T, Caldwell LC, Strong LC, El-Naggar AK, Lozano G. Gain of function of a p53 hot spot mutation in a mouse model of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004;119:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Olive KP, Tuveson DA, Ruhe ZC, Yin B, Willis NA, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Jacks T. Mutant p53 gain of function in two mouse models of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004;119:847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bougeard G, Sesboue R, Baert-Desurmont S, Vasseur S, Martin C, Tinat J, Brugieres L, Chompret A, de Paillerets BB, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Bonaiti-Pellie C, Frebourg T, French L.F.S.w.g. Molecular basis of the Li-Fraumeni syndrome: an update from the French LFS families. J Med Genet. 2008;45:535–538. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.057570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Freed-Pastor WA, Mizuno H, Zhao X, Langerod A, Moon SH, Rodriguez-Barrueco R, Barsotti A, Chicas A, Li W, Polotskaia A, Bissell MJ, Osborne TF, Tian B, Lowe SW, Silva JM, Borresen-Dale AL, Levine AJ, Bargonetti J, Prives C. Mutant p53 disrupts mammary tissue architecture via the mevalonate pathway. Cell. 2012;148:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Clendening JW, Pandyra A, Boutros PC, El Ghamrasni S, Khosravi F, Trentin GA, Martirosyan A, Hakem A, Hakem R, Jurisica I, Penn LZ. Dysregulation of the mevalonate pathway promotes transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15051–15056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910258107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koyuturk M, Ersoz M, Altiok N. Simvastatin induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cells: p53 and estrogen receptor independent pathway requiring signalling through JNK. Cancer Lett. 2007;250:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang C, Liu J, Liang Y, Wu R, Zhao Y, Hong X, Lin M, Yu H, Liu L, Levine AJ, Hu W, Feng Z. Tumor-Associated Mutant p53 Drives the Warburg Effect. Nature Communications. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3935. 10.1038/ncomms3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goel A, Mathupala SP, Pedersen PL. Glucose metabolism in cancer. Evidence that demethylation events play a role in activating type II hexokinase gene expression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:15333–15340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chavez-Perez VA, Strasberg-Rieber M, Rieber M. Metabolic utilization of exogenous pyruvate by mutant p53 (R175H) human melanoma cells promotes survival under glucose depletion. Cancer biology & therapy. 2011;12:647–656. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.7.16566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]