Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the feasibility, safety, and oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic extended right hemicolectomy (LERH) for colon cancer.

METHODS: Since its establishment in 2009, the Southern Chinese Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgical Study (SCLCSS) group has been dedicated to promoting patients’ quality of life through minimally invasive surgery. The multicenter database was launched by combining existing datasets from members of the SCLCSS group. The study enrolled 220 consecutive patients who were recorded in the multicenter retrospective database and underwent either LERH (n = 119) or open extended right hemicolectomy (OERH) (n = 101) for colon cancer. Clinical characteristics, surgical outcomes, and oncologic outcomes were compared between the two groups.

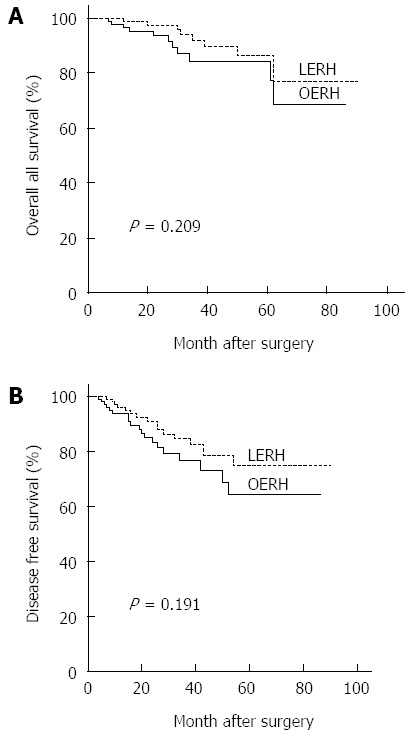

RESULTS: There were no significant differences in terms of age, gender, body mass index (BMI), history of previous abdominal surgery, tumor location, and tumor stage between the two groups. The blood loss was lower in the LERH group than in the OERH group [100 (100-200) mL vs 150 (100-200) mL, P < 0.0001]. The LERH group was associated with earlier first flatus (2.7 ± 1.0 d vs 3.2 ± 0.9 d, P < 0.0001) and resumption of liquid diet (3.6 ± 1.0 d vs 4.2 ± 1.0 d, P < 0.0001) compared to the OERH group. The postoperative hospital stay was significantly shorter in the LERH group (11.4 ± 4.7 d vs 12.8 ± 5.6 d, P = 0.009) than in the OERH group. The complication rate was 11.8% and 17.6% in the LERH and OERH groups, respectively (P = 0.215). Both 3-year overall survival [LERH (92.0%) vs OERH (84.4%), P = 0.209] and 3-year disease-free survival [LERH (84.6%) vs OERH (76.6%), P = 0.191] were comparable between the two groups.

CONCLUSION: LERH with D3 lymphadenectomy for colon cancer is a technically feasible and safe procedure, yielding comparable short-term oncologic outcomes to those of open surgery.

Keywords: Colon cancer, Laparoscopic surgery, Extended right hemicolectomy, D3 lymphadenectomy, Survival

Core tip: This multicenter retrospective study specially evaluates the feasibility, safety, and oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic extended right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy for tumors located at the hepatic flexure or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure. Results suggest that laparoscopic extended right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy is a technically feasible and safe procedure, yielding comparable short-term oncologic outcomes to open surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic colectomy has become accepted as an alternative to conventional open surgery for the treatment of colon cancer because of the earlier recovery and comparable long-term results[1-4]. However, most previous studies excluded tumors located at the hepatic flexure or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure because of the technical difficulty associated with such sites. A tumor located at or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure has an increased risk of infra-pyloric lymph node metastasis[5]. Consequently, open extended right hemicolectomy (OERH) with D3 lymphadenectomy has been recommended as the optional procedure[6].

Although the feasibility and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy for right colon cancer have been reported in several previous studies[7,8], the lymphadenectomy did not include the infra-pyloric lymph nodes. Thus, the role of laparoscopic extended right hemicolectomy (LERH) with D3 lymphadenectomy for cancer located at or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure is unknown.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the surgical feasibility, safety, and oncologic outcomes of LERH based on a multicenter dataset from 11 specialized institutions in Southern China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Database and patients

Since its establishment in 2009, the Southern Chinese Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgical Study (SCLCSS) group has been dedicated to promoting patients’ quality of life through minimally invasive surgery. The multicenter database was launched by combining existing datasets from members of the SCLCSS group. The clinical data of 3640 consecutive colon cancer patients who underwent either open (n = 2419) or laparoscopic (n = 1221) surgery at 11 specialized institutions between January 2000 and June 2009 were recorded in the database[9]. All data were documented respectively using unified case report form (CRF) and the data collection protocol was approved by the local ethics committees. All participants signed informed consent statements.

A total of 247 patients who underwent extended right hemicolectomy for cancer located at the hepatic flexure or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure were registered from May 2006 to May 2009 in our database. Twenty-seven patients were excluded from the present analysis due to advanced stage (stage IV), recurrent disease, emergency surgery, or palliative surgery. Finally, a total of 220 consecutive patients who underwent either LERH (n = 119) or OERH (n = 101) were included in the present series. The surgical approach was chosen based on an understanding of the risks and benefits inherent to laparoscopic and open resection, without any pressure from the surgeon.

Indications and data collection

Extended right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy was implemented with radical intention when the patient was confirmed with colon cancer located at the hepatic flexure or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure and the clinical stage was II or III at preoperative examination by colonoscopy, abdominal enhanced computed tomography, and chest X-ray. The clinical characteristics, surgical outcomes, and oncologic outcomes of patients in the two groups were compared. The NCCN guidelines for colon cancer (v.1.2012) were used for clinical and pathological staging.

Extended right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy

The patient was placed in the supine position with legs apart during LERH with D3 lymphadenectomy. A 10-mm 30° rigid laparoscope was used through an observational port located at the umbilicus. A 12-mm trocar located 10 cm below the umbilicus, and a 5-mm trocar at McBurney’s point were placed for surgeon standing between the legs. Two other 5-mm trocars, located at the opposite McBurney’s point and the left subcostal area, were used for assistance. A medial-to-lateral approach was used during the LERH. In the medial dissection, the D3 lymphadenectomy involved sequential dissection (central ligation) at the roots of the ileocolic vessels, right colic vessels, middle colic vessels, and right gastroepiploic vessels. The subsequent colon dissection involved 10 cm of normal bowel distal to the lesion and at least 10 cm of distal ileum. An extracorporeal functional end-to-end or side-to-side ileotransverse colon anastomosis was performed via a 3- to 5-cm paramidline incision.

During OERH, a lateral-to-medial approach was used for D3 lymphadenectomy and mobilization of colon. A 15- to 20-cm right upper quadrant incision was used. The resection range of colon and mesocolon and D3 lymphadenectomy was performed as the same as the procedures in the LERH. A functional end-to-end or side-to-side ileotransverse colon anastomosis was then constructed.

Although there were differences between the centers in the surgical instruments, vessel occlusion, and the operative approach (lateral-to-medial in LERH) in a minority of operations, the majority of procedures in most of the centers were implemented as above.

Definitions

A major complication was defined as any complication requiring reoperation or interventional therapy, and a minor complication was defined as a complication that could be managed conservatively. Overall survival was calculated from the operation date to the date of death from all causes. Disease-free survival was calculated from the operation date to the date of recurrence or metastasis. In this study, patients with a high-risk stage II or stage III tumor were recommended to receive postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil-based regimens. The last follow-up was in September 2009.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t test and expressed as mean ± SD and variables with non-normal distribution were reported as the median (range). Categorical variables were compared using the pearson χ2 test or the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. The survival data were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 16.0).

RESULTS

Clinicopathologic characteristics

The patients’ clinicopathologic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of patients in the LERH and OERH group was 61.3 and 64.5 years, respectively. There were no significant differences in age, gender, body mass index (BMI), history of previous abdominal surgery, tumor location, and tumor stage between the two groups.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics n (%)

| LERH (n = 119) | OERH (n = 101) | P value | |

| Age1 (yr) | 61.3 ± 25.3 | 64.5 ± 24.6 | 0.832 |

| Sex | 0.893 | ||

| Male | 66 (55.5) | 57 (56.4) | |

| Female | 53 (44.5) | 44 (43.6) | |

| Body mass index1 (kg/m2) | 22.3 ± 3.3 | 22.6 ± 3.5 | 0.126 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 12 (10.1) | 14 (13.9) | 0.387 |

| Tumor location | 0.105 | ||

| Hepatic flexure | 89 (74.8) | 65 (64.4) | |

| Proximal of transverse colon | 30 (25.2) | 36 (35.6) | |

| Tumor size1 (cm) | 4.8 ± 1.9 | 4.7 ± 1.7 | 0.849 |

| T stage | 0.483 | ||

| T2 | 6 (5.0) | 7 (6.9) | |

| T3 | 64 (53.8) | 60 (59.4) | |

| T4 | 49 (41.2) | 34 (33.7) | |

| N stage | 0.870 | ||

| N0 | 69 (58.0) | 61 (60.4) | |

| N1 | 37 (31.1) | 31 (30.7) | |

| N2 | 13 (10.9) | 9 (8.9) | |

| Tumor stage | 0.815 | ||

| I | 6 (5.0) | 7 (6.9) | |

| II | 63 (52.9) | 54 (53.5) | |

| III | 50 (42.0) | 40 (39.6) |

Values are mean ± SD. LERH: Laparoscopic extended right hemicolectomy; OERH: Open extended right hemicolectomy.

Operative outcomes

The mean operative time was significantly longer in the LERH group than that in the OERH group (257.8 ± 67.6 min vs 173.1 ± 52.0 min, P < 0.0001). However, estimated blood loss was lower in the LERH group compared with the OERH group [100 (100-200) mL vs 150 (100-200) mL, P < 0.0001]. There were no significant differences in tumor size, length of resection margins, number of lymph nodes harvested, or the pathologic R0 resection. Conversion was required in nine patients (7.6%) in the LERH group. The reasons for conversion were technically difficult dissection in four patients, severe adhesion in three patients, and uncontrolled bleeding in two patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Operative outcomes n (%)

| LERH (n = 119) | OERH (n = 101) | P value | |

| Operating time1 (min) | 257.8 ± 67.6 | 173.1 ± 52.0 | < 0.0001 |

| Estimated blood loss2 (mL) | 100 (100-200) | 150 (100-200) | < 0.0001 |

| Proximal resection margin1 (cm) | 17.1 ± 3.3 | 17.2 ± 3.2 | 0.743 |

| Distal resection margin1 (cm) | 13.9 ± 2.6 | 14.3 ± 3.6 | 0.133 |

| No. of lymph nodes harvested1 (n) | 22.3 ± 8.6 | 21.8 ± 9.4 | 0.343 |

| Conversions | 9 (7.6) | ||

| R0 resection | 117 (98.3) | 100 (99.0) | 1.000 |

Values are mean ± SD;

value is median (range). LERH: Laparoscopic extended right hemicolectomy; OERH: Open extended right hemicolectomy.

Postoperative recovery

The mean time to first flatus (2.7 ± 1.0 d vs 3.2 ± 0.9 d, P < 0.0001), start of a liquid diet (3.6 ± 1.0 d vs 4.2 ± 1.0 d, P < 0.0001), and postoperative hospital stay (11.4 ± 4.7 d vs 12.8 ± 5.6 d, P = 0.009) were significantly shorter in the LERH group than in the OERH group. Postoperative complications occurred in 14 patients (11.8%) in the LERH group and 18 patients (17.6%) in the OERH group (P = 0.215). Major complications were experienced by two patients (1.7%) in the LERH group (anastomotic stenosis and ileus in one patient each) and three patients (3.0%) in the OERH group (anastomotic stenosis, ileus, and hemorrhage in one patient each) (P = 0.663). Minor complications occurred in 12 patients (10.1%) in the LERH group and 15 patients (14.9%) in the OERH group (P = 0.308). The mortality rate within 30 d after surgery between the two groups was comparable (0.8% vs 1.0%, P = 0.907) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Postoperative recovery and complications n (%)

| LERH (n = 119) | OERH (n = 101) | P value | |

| Time to first flatus1 (d) | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | < 0.0001 |

| Time to liquid diet1 (d) | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 4.2 ± 1.0 | < 0.0001 |

| Hospital stay1 (d) | 11.4 ± 4.7 | 12.8 ± 5.6 | 0.009 |

| Complications | 14 (11.8) | 18 (17.6) | 0.215 |

| Wound infection | 4 (3.4) | 8 (7.8) | |

| Ileus | 4 (3.4) | 4 (3.9) | |

| Anastomotic leak | 2 (1.7) | 4 (3.9) | |

| Anastomotic stenosis | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Introabdominal hemorrhage | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Abdominal infection | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mortality | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.0) | 0.907 |

Values are mean ± SD. LERH: Laparoscopic extended right hemicolectomy; OERH: Open extended right hemicolectomy.

Survival outcomes

Seven patients (5.9%) in the LERH group and eight patients (7.8%) in the OERH group were lost to follow-up. The median duration of follow-up was 30 mo (range 3-60 mo) for the LERH group and 27 mo (range 4-60 mo) for the OERH group (P = 0.632). The 3-year cumulative overall survival was 92.0% in the LERH group and 84.4% in the OERH group (P = 0.209) (Figure 1A). The 3-year cumulative disease-free survival was 84.6% in the LERH group and 76.6% in the OERH group (P = 0.191) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Survival outcomes. A: Cumulative overall survival rate during a 3-year interval in the LERH and OERH groups (92.0% vs 84.4%, P = 0.209; Log-rank test); B: Cumulative disease-free survival rate during a 3-year interval in the LERH and OERH groups (84.6% vs 76.6%, P = 0.191; Log-rank test). LERH: Laparoscopic extended right hemicolectomy; OERH: Open extended right hemicolectomy.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, LERH showed several short-term advantages compared with OERH in terms of blood loss, postoperative hospitalization, and resumption of gastrointestinal function, with comparable clinicopathologic characteristics and postoperative complications. The short-term oncologic outcomes were comparable between the LERH group and the OERH group.

Adequate lymph node dissection is associated with improved survival[10,11]. Before 2005, the Japanese General Rules for Clinical and Pathologic Studies on Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JGR) recommended that colectomy for cancer should be performed with at least 5- to 10-cm long proximal and distal margins and that the regional arterial vessels should be ligated at their origins. The Japanese guidelines also recommended that patients with tumor invasion depth of T3 or deeper should undergo adequate colonic resection with D3 lymphadenectomy[12].

Lymphatic fluid streams from the transverse colon to lymph nodes along the gastroepiploic vessels[13]. For a tumor located at the hepatic flexure or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure, approximately 4% of lymph nodes along the gastroepiploic arcade at the greater curvature of the stomach and 6% of lymph nodes along the root of middle colic artery would be involved[5]. The standard protocol for right hemicolectomy involves resection of the right branch of the middle colic artery with preservation of the left branch[6,14]. Thus, the rate of loco-regional recurrence after right hemicolectomy for cancer located at the hepatic flexure or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure is higher[15,16]. This might be attributed to the limited resection that did not remove the nodes at the root of the common trunk of the middle colic artery or those at the infrapyloric region. Accordingly, when cancer is located at or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure, extended right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy is appropriate to ensure radicality. However, the surgical safety of LERH was unclear because of the difficult dissection of the central lymph nodes along either the root of the middle colic artery or the right gastroepiploic vessels.

The time to liquid diet and the postoperative hospital stay were longer in this study than in previous reports[7,17]. These differences might be because a fast-track recovery strategy was not performed routinely in the clinical care of most of our centers during the early period. The extended lymphadenectomy may be another reason for the relatively late postoperative recovery.

Lower overall morbidity and reduced risk of severe complications are potential advantages of laparoscopic colectomy compared with open surgery[18]. Although there was no statistical significance, in the present study the postoperative complication rate was lower in the LERH group compared with the OERH group.

Conversion rates in randomized controlled trials comparing laparoscopic with open colectomy ranged from 11% to 25%[19-21] and the main cause of conversion in laparoscopic colectomy for cancer was local tumor progression[22,23]. Previous studies = have shown that conversion resulted in increased operating time, increased hospital stay, and more importantly, increased morbidity and decreased short-term survival[24-26]. In the present study, among the nine cases that converted to open surgery, four were T4a lesions. Both of the conversions (2/9, 22.2%) due to uncontrolled bleeding occurred during dissection of the root of the right gastroepiploic artery, which is considered a difficult aspect of this laparoscopic procedure.

The limited reports on D3 lymphadenectomy for right colon cancer included only 5 (11.9%) and 32 (18.1%) cases of hepatic flexure colon cancer; moreover, previous studies only reported extended right hemicolectomy for hepatic flexure colon cancer without dissection of the lymph node at the infrapyloric region[7,8]. In the present series, the 3-year overall survival rate was 92.0% in the LERH group, compared with the reported 83.73% for laparoscopic surgery without infrapyloric lymphadenectomy[8].

Although a novel concept for colon cancer surgery, complete mesocolic excision (CME) reported by Hohenberger et al[27] has become a standard procedure. Both the Japanese procedure of D3 lymphadenectomy and the European approach of CME for colon cancer have been reported to be associated with improved overall survival[27,28], and recent research showed equivalent efficacy between D3 surgery and CME for colon cancer[29]. During the past two decades, colectomy for colon cancer performed in most of the medical centers in China has been based on the Japanese D3 lymphadenectomy principle.

Limitations

This study is subject to several limitations. Firstly, the retrospective design has the inherent weakness of being observational or nonexperimental. Secondly, the findings may lack generalizability due to the relatively short median follow-up time. Nonetheless, this multicenter study suggests a role of laparoscopic extended right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy for the treatment of cancer located at or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure.

Results of this study suggest that for colon cancer located at the hepatic flexure or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure, LERH with D3 lymphadenectomy is a technically feasible and safe procedure, yielding comparable short-term oncologic outcomes to open surgery. However, studies of long-term effects in randomized clinical trials are warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the following participating investigators who allowed their clinical experience to be included in this study: Min-Gang Ying, Fujian Provincial Tumor Hospital (Fuzhou); Zong-Hai Huang, Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University (Guangzhou); Zhen-Xing Rong, The First People’s Hospital of Shunde (Shunde); Feng Lin, Guangdong General Hospital (Guangzhou); Chu-Yuan Hong, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou); HB Wei, The third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University (Guangzhou).

COMMENTS

Background

Laparoscopic colectomy for the treatment of colon cancer has been accepted because of the earlier recovery and comparable long-term results based on a number of randomized controlled trails (RCTs). Laparoscopic extended right hemicolectomy (LERH) with D3 lymphadenectomy for colon cancer was excluded from majority of the RCTs because of the technical difficulty.

Research frontiers

Laparoscopic surgery has been suggested as an alternative treatment for colon cancer because of both the short-term advantages and the comparable long-term oncologic outcomes when compared to open surgery. LERH with D3 lymphadenectomy was performed cautiously because it is highly technically demanding. With the improvement in surgical techniques, surgeon’s experience, and renewal instruments, extended right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy has subsequently been attempted in laparoscopic surgery.

Innovations and breakthroughs

LERH with D3 lymphadenectomy is challenging mainly because of technical difficulty in dissecting the lymph nodes around the origin of the middle colic vessels and right gastroepiploic vessels, and handling the intricacies of venous anatomy at the gastrocolic trunk of Henle. This multicenter retrospective study evaluates the feasibility, safety, and oncologic outcomes of LERH with D3 lymphadenectomy. The superior short-term outcomes and equivalent 3-year oncologic outcomes suggest that LERH with D3 lymphadenectomy should not be excluded from the management of the patients with tumor located at the hepatic flexure or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure.

Applications

The study results suggest that LERH with D3 lymphadenectomy for colon cancer is a technically feasible and safe procedure, yielding comparable 3-year oncologic outcomes to those of open surgery.

Terminology

Tumor located at or within 10 cm distal to the hepatic flexure has an increased risk of infra-pyloric lymph node metastasis. Extended right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy which was defined as the ileocolic, right colic, middle colic, and right gastroepiploic vessels were ligated at their origins in sequence and the bowel mobilization was performed at least 10 cm from the margins of the tumor.

Peer review

The authors reported a well written and interesting paper in the field of mini-invasive right colon surgery. The results are clear and well described.

Footnotes

Supported by National High Technology Research and Development Program of China, No. 2012AA021103; the Program of Guangdong Provincial Department of Science and Technology, No. 2012A030400012; the Major Program of Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, No. 201300000087; and the Sub-project under National Science and Technology Support Program, No. 2013BAI05B00

P- Reviewers: Capasso R, Marinis AD, Trastulli S S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Veldkamp R, Kuhry E, Hop WC, Jeekel J, Kazemier G, Bonjer HJ, Haglind E, Påhlman L, Cuesta MA, Msika S, et al. Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:477–484. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleshman J, Sargent DJ, Green E, Anvari M, Stryker SJ, Beart RW, Hellinger M, Flanagan R, Peters W, Nelson H. Laparoscopic colectomy for cancer is not inferior to open surgery based on 5-year data from the COST Study Group trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:655–662; discussion 662-664. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai HL, Chen B, Zhou Y, Wu XT. Five-year long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4992–4997. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i39.4992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buunen M, Veldkamp R, Hop WC, Kuhry E, Jeekel J, Haglind E, Påhlman L, Cuesta MA, Msika S, Morino M, et al. Survival after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: long-term outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:44–52. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toyota S, Ohta H, Anazawa S. Rationale for extent of lymph node dissection for right colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:705–711. doi: 10.1007/BF02048026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Block GE, Moossa AR. Operative colorectal surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Pub; 1994. pp. 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SD, Lim SB. D3 lymphadenectomy using a medial to lateral approach for curable right-sided colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:295–300. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0597-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han DP, Lu AG, Feng H, Wang PX, Cao QF, Zong YP, Feng B, Zheng MH. Long-term results of laparoscopy-assisted radical right hemicolectomy with D3 lymphadenectomy: clinical analysis with 177 cases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:623–629. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1605-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang YZ, Yu J, Zhang C, Wang YN, Cheng X, Huang F, Li GX. [Construction and application of evaluation system of laparoscopic colorectal surgery based on clinical data mining] Zhonghua Weichang Waike Zazhi. 2010;13:741–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang GJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Skibber JM, Moyer VA. Lymph node evaluation and survival after curative resection of colon cancer: systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:433–441. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vather R, Sammour T, Kahokehr A, Connolly AB, Hill AG. Lymph node evaluation and long-term survival in Stage II and Stage III colon cancer: a national study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:585–593. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. The Guidelines for Therapy of Colorectal Cancer (in Japanese) Tokyo: Kanehara Shuppan Pub; 2005. pp. 72–73. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamieson JK, Dobson JF. VII. Lymphatics of the Colon: With Special Reference to the Operative Treatment of Cancer of the Colon. Ann Surg. 1909;50:1077–1090. doi: 10.1097/00000658-190912000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goligher IC. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum and Colon. 5thed. London: Bailliere Tindall Pub; 1984. pp. 234–237. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sjövall A, Granath F, Cedermark B, Glimelius B, Holm T. Loco-regional recurrence from colon cancer: a population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:432–440. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9243-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West NP, Morris EJ, Rotimi O, Cairns A, Finan PJ, Quirke P. Pathology grading of colon cancer surgical resection and its association with survival: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:857–865. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsikitis VL, Holubar SD, Dozois EJ, Cima RR, Pemberton JH, Larson DW. Advantages of fast-track recovery after laparoscopic right hemicolectomy for colon cancer. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1911–1916. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0871-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dwivedi A, Chahin F, Agrawal S, Chau WY, Tootla A, Tootla F, Silva YJ. Laparoscopic colectomy vs. open colectomy for sigmoid diverticular disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1309–1314; discussion 1314-1315. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6415-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacy AM, García-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, Castells A, Taurá P, Piqué JM, Visa J. Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2224–2229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weeks JC, Nelson H, Gelber S, Sargent D, Schroeder G. Short-term quality-of-life outcomes following laparoscopic-assisted colectomy vs open colectomy for colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2002;287:321–328. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simorov A, Shaligram A, Shostrom V, Boilesen E, Thompson J, Oleynikov D. Laparoscopic colon resection trends in utilization and rate of conversion to open procedure: a national database review of academic medical centers. Ann Surg. 2012;256:462–468. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182657ec5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorpe H, Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Copeland J, Brown JM, Medical Research Council Conventional versus Laparoscopic-Assisted Surgery In Colorectal Cancer Trial Group. Patient factors influencing conversion from laparoscopically assisted to open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2008;95:199–205. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarnowski W, Uryszek M, Grous A, Dib N. Intraoperative difficulties and the reasons for conversion in patients treated with laparoscopic colorectal tumors. Pol Przegl Chir. 2012;84:352–357. doi: 10.2478/v10035-012-0059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hewett PJ, Allardyce RA, Bagshaw PF, Frampton CM, Frizelle FA, Rieger NA, Smith JS, Solomon MJ, Stephens JH, Stevenson AR. Short-term outcomes of the Australasian randomized clinical study comparing laparoscopic and conventional open surgical treatments for colon cancer: the ALCCaS trial. Ann Surg. 2008;248:728–738. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818b7595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1718–1726. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rottoli M, Stocchi L, Geisler DP, Kiran RP. Laparoscopic colorectal resection for cancer: effects of conversion on long-term oncologic outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1971–1976. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hohenberger W, Weber K, Matzel K, Papadopoulos T, Merkel S. Standardized surgery for colonic cancer: complete mesocolic excision and central ligation--technical notes and outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:354–364; discussion 364-365. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.West NP, Hohenberger W, Weber K, Perrakis A, Finan PJ, Quirke P. Complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation produces an oncologically superior specimen compared with standard surgery for carcinoma of the colon. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:272–278. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West NP, Kobayashi H, Takahashi K, Perrakis A, Weber K, Hohenberger W, Sugihara K, Quirke P. Understanding optimal colonic cancer surgery: comparison of Japanese D3 resection and European complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1763–1769. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]