Abstract

Little is known about the factors associated with use of employment services among homeless youth. Social network characteristics have been known to be influential in motivating people's decision to seek services. Traditional theoretical frameworks applied to studies of service use emphasize individual factors over social contexts and interactions. Using key social network, social capital, and social influence theories, this paper developed an integrated theoretical framework that could capture the social network processes that act as barriers or facilitators of use of employment services by homeless youth, and understand empirically, the salience of each of these constructs in influencing the use of employment services among homeless youth. We used the “Event based-approach” strategy to recruit a sample of 136 homeless youth at one drop-in agency serving homeless youth in Los Angeles, California in 2008. The participants were queried regarding their individual and network characteristics. Data were entered into NetDraw 2.090 and the spring embedder routine was used to generate the network visualizations. Logistic regression was used to assess the influence of the network characteristics on use of employment services. The study findings suggest that social capital is more significant in understanding why homeless youth use employment services, relative to network structure and network influence. In particular, bonding and bridging social capital were found to have differential effects on use of employment services among this population. The results from this study provide specific directions for interventions aimed to increase use of employment services among homeless youth.

Keywords: homeless youth, employment services, social networks, social capital

1. Introduction

1.1. Homelessness among youth and the perilous course to stability

Approximately 1.6 million youth experience homelessness in a given year in the United States, and homelessness among youth and young adults remains a major social concern (Toro, Dworsky, & Fowler, 2007). Annual estimates of these unaccompanied youth in Los Angeles County have ranged between 4,800 and 10,000 (Kipke, Montgomery, Simon, & Iverson, 1997; L.A. Homeless Services Authority, 2001), making it one of the largest populations of unaccompanied youth in the country. It is believed that youth and young adults are less likely to stay homeless if they are self-sufficient and stably employed (Toro et al., 2007). Unemployment rates among homeless youth however continue to be high ranging from 66 to 71% (Ferguson, Xie, & Glynn, 2012). Therefore, an increased emphasis has been placed on training homeless youth to live and function independently in society (Lenz-Rashid, 2006). For example, the Youth services and Job Corp programs funded through the Workforce Investment Act both include homeless youth as a target population (Hook & Courtney, 2011). Accordingly, a number of agencies serving homeless youth offer employment services training and support to homeless youth. In spite of this policy and practice focus on supporting homeless youth in obtaining employment, studies show that homeless youth are less likely to be employed and even less likely to utilize employment services compared to housed youth (Courtney, Dworsky, Lee, Raap, & Hall, 2010; Hook & Courtney, 2011).

1.2. A social network approach to understanding the use of employment services

Studies that have examined homelessness among adolescents and young adults, have often cast the problem as one of individual vulnerabilities rather than as a social phenomenon involving transactions between individuals and their environments (Haber & Toro, 2004). In a similar vein, conventional models applied to studies of service use propose conceptual models based on individual factors such as motivation, attitudinal perception, and rational evaluation (Carpentier & White, 2002). This theoretical perspective is increasingly being called into question, because it neglects social contexts and interactions linked to the process of help seeking (Carpentier & White, 2002). A network approach to understanding human behavior is able to mitigate the limitations of these narrow theorizations because it operates on the understanding that a person’s social structure is composed of an array of relationships and these relationships influence the way in which people act (Scott & Hofmeyer, 2007). Using key social network, social capital, and social influence theories, this study developed an integrated theoretical framework capturing the social network processes that can act as barriers or facilitators of use of employment services by homeless youth. Rather than testing the predictive power of this model, the purpose in constructing this model was to identify conceptually driven social-network correlates of employment services utilization among homeless youth. This allowed us to assess the relative importance of each of these network dimensions and provide direction for future network based interventions that aim to develop or tailor employment services for homeless youth.

Literature Review

2.1. Characteristics of homeless youth and transitions to employment

Homeless youth are by nature a transient population. There are various ways in which homeless youth have been defined and classified. For the purposes of this study, we used the definition put forth by Tsemberis, McHugo, Williams, Hanrahan, and Stefancic (2004) as our criteria for delineating whether youth were homeless. This definition includes categories of literally homeless, temporary homeless, institutional residence, stable residence, and functional homeless. This definition is considered more comprehensive in its criteria and representativeness of homelessness than most other definitions. Moreover, unlike the federal definition of homelessness, which has been characterized as obscuring the intensity of the problem, this definition acknowledges that homelessness encompasses a broad spectrum of people. This range of homeless includes not only those living on the streets and in shelters but also those living in motels or with family and friends because of economic hardship.

Homeless youth, however, face a number of barriers in finding employment such as lack of experience, poor academic preparation, disruptive behavior, and poor communication skills (Courtney, Terao, & Bost, 2004). Not surprisingly, a recent study conducted to assess income generation sources among homeless youth found that a majority of these youth relied on illicit activities to generate income. In this study, only 28% of these youth relied on formal employment for income, while 53% of the respondents indicated that they engaged in survival behaviors (such as panhandling, stealing, dealing drugs, prostitution etc.) to generate income (Ferguson et al., 2012). Becoming gainfully employed might be able to contribute to these youth’s identity formation, connect them to conventional institutions, provide income that facilitates economic self-sufficiency, and reduce the chances of engaging in risky subsistence strategies (such as panhandling, dealing drugs, and exchange sex) (Ferguson, Xie, & Glynn, 2012).Therefore, it is important that homeless youth be given the support and skills that they need in securing stable and secure employment.

Employment services generally offer homeless youth employment skills including professional behavior, work ethics, job search and retention, internships, tutoring, GED tutoring and classes, secondary and post-secondary school enrollment and support writing, and customer service. Unfortunately, little is known about the factors associated with the use of employment services among this population, leaving policymakers and providers with little evidence to tailor their programs to fit the needs and profiles of these youth.

2.2. Use of employment services among homeless youth

A vast majority of the literature on homeless youth’s service participation has been limited to the utilization of health, mental health, and substance abuse treatment services. Despite the lack of focus on employment services among homeless youth, these studies investigating associations with other kinds of services can be helpful in identifying correlates of use of employment services in this population.

It is important to acknowledge that homeless youth are a complex, diverse, and heterogeneous population; and this heterogeneity has implications for service use among homeless youth (Pergamit, Ernst, & Hall, 2010). Gender has been especially found to be an important correlate of service use among this population; with females being more likely than males to access mental health treatment (Berdahl et al., 2005), medical services (De Rosa et al. 1999; Klein et al., 2000) and HIV testing services (Solorio et al., 2006; Tyler et al., 2012). Race has been associated with both utilization and underutilization of services. Geber (1997) found that minority youth reported barriers to service utilization on grounds of racial/ethnic discrimination. On the other hand, De Rosa et al. (1999) found that racial minority youth were more likely to use shelters relative to White youth. Another significant aspect of homeless youth’s likelihood of accessing services depends on their life cycle of homelessness (Carlson et al., 2006). Studies have found that the longer youth are homeless, the less likely they are to engage in services. Similarly, significant differences have been found between sheltered and unstably housed youth in their reports of utilization of services (Berdahl et al., 2005; Sweat et al., 2008). However, most of these studies were only able to account for a minor proportion of the variance in explaining the use or non-use of services; it is likely that social-contextual factors will be able to explain what these individual factors do not account for.

2.3.The potential contribution of social network factors to use of employment services

The role of social-network factors in predicting service use in general and employment services in particular has received little empirical attention (Garland, Lau, Yeh, McCabe, Hough, & Landsverk, 2005). However, a few studies (Kipke et al., 1997; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999; Reid & Klee, 1999; van Wormer, 2003; Chew Ng, Muth, & Auerswald, 2013) have uncovered promising findings on the role that social networks can play in influencing the choice of services among homeless youth; however the evidence is sparse and is not as consistent as one would hope.

In general, these studies found that homeless youth maintain both street and non-street relationships and the instrumental or emotional resources that they receive from these people influence the use of services among homeless youth. It is however important to note that social networks do not always provide positive resources; some types of resource or support offered by a social network’s members may increase distress or engagement in unhealthy behaviors (Lincoln, 2000). For example, receiving instrumental help from other street youth is often associated with participation in the street economy and negates the development of conventional competencies and adjustment (Whitbeck, 2009). Therefore, it is not surprising to find that among certain street groups, use of shelters is viewed as antithetical to the conventions of street life, and affiliation with these groups serves as an impediment to the use of shelters (Garrett et al., 2008). Therefore, one can surmise that receiving support from other homeless youth could be associated with reduced use of services.

However, street peers can also assist with the use of services. Street peers often act as behavioral models for service use and homeless youth report learning about resource availability or services from networking with their street peers (Reid & Klee, 1999; Garrett, Higa, Phares, Peterson, Wells, & Baer, 2008). For instance, one recent study found that homeless youth who associated with other shelter users were five times more likely to use shelters themselves (Chew Ng, Muth, & Auerswald, 2013).

Similarly, having connections with or receiving instrumental and emotional help from non-street relationships (such as parents, other family members, and home-based friends) can also facilitate or hinder the use of services. Increased contact with parents and other family members have been known to deter youth from looking for jobs because of the instrumental help that they receive from these relationships (Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). However, the opposite might also be true. Two studies have indicated that family and home-based friends are instrumental in influencing youth’s decision in transitioning from street life and engaging in services that would provide them, a viable means of becoming self-sufficient (Kurtz, Lindsey, Jarvis, & Nackerud, 2000; Raleigh-Duroff, 2004). We are not aware of studies that have assessed the impact of youth’s position in a larger network of relationships (network structure) on use of services (including the use of employment services) among homeless youth. However, in assessing other risk behaviors among homeless youth (such as HIV risk and drug use), being in the core (or the center) of a network of other homeless youth has been associated with greater risk behaviors (Rice, Barman-Adhikari, Milburn, & Monro, 2012). Clearly, there is a great deal to learn about how network structure, function and its influence affect homeless youth’s utilization of employment services.

While these aforementioned studies shed light on some of the social-network factors associated with service use among homeless youth, there are important limitations in their methodology. Most of the studies summarized here have been either qualitative or based on individual level data. While this does not undermine the contribution that they make to the literature, collecting detailed social network data enables researchers to understand with more specificity, people’s social embeddedness, the kind of relationships that people have, the kind of functions that these relationships offer, and the influence that they cast on the individual (Barrera, 1986;Wasserman & Galakiewicz, 1994). More importantly, using this methodology, it becomes possible to delineate what kind of resources (instrumental and emotional) is received from each of these relationships. Previous research has found that these diverse forms of source-specific resources have differential effects on service use (Broadhead, Gehlbach, DeGruy, & Kaplan, 1998; DiMatteo, 2004). Social network analysis includes analyses of egocentric networks where the individual is at the center of the network as well as entire networks of communities (also known as sociometric analyses). This current study utilizes a sociometric design, which would reveal whether a youth’s embeddedness in the street network (or his/her position in the larger network) is associated with the use of employment services in this population.

3. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework proposed in this paper is predicated on a social-network perspective, which assumes that social behaviors are not entirely rational choices but are socially prescribed (Latkin & Knowlton, 2005). As an organizing framework, this study distinguishes between three types of network attributes- network structure, network function, and network influence. Structural Network theory, Social Capital theory, and Social Influence theory provide insights into the mechanisms through which the three afore-mentioned social network attributes affect the utilization of employment services among homeless youth. Following is an elaboration of these three network dimensions and how they each relate to employment services among homeless youth.

3.1. Structural Network Theory

A network consists of a set of nodes (or actors) along with a set of ties that connect them (Wasserman & Galaskiewicz, 1994). Structural network theory is primarily concerned with characterizing network structures (e.g. small worldness) and node positions (e.g. core/periphery) and associating it with a multitude of outcomes, including job performance, mental health, organizational success etc. (Borgatti & Halgin, 2011). Social network analysis with homeless youth has been conceptualized as a way of measuring homeless youth’s immersion into street culture (Whitbeck, 2009) and sociometric data helps us assess precisely how a youth is positioned vis-à-vis others in a network of other homeless youth. Theoretically, youth who are positioned in different social locations in the network (such as the core or the periphery) might vary in their employment service use because of various reasons. Placement in these social positions reflects varying levels of interaction with their street-peers (Ennett & Bauman, 1993). Youth who are in the core or center of their street networks might adhere more closely to the norms of their street-peer group and might shun assistance such as employment services. On the other hand, youth who are in the periphery might have access to diverse opportunities for obtaining information, ideas, and resources from many different sources and be less constrained by the influence of their street-peers. These ideas find some resonance in the empirical literature as well. One of the few studies that examined the associations between peer affiliation and service use among homeless youth found that being a “loner” was associated with less risky subsistence strategies and increased reliance on government benefits (Kipke et al., 1997). Based on these theoretical propositions, one can hypothesize that being in the core of this network will be associated with the reduced likelihood of engagement in employment services.

3.2. Social Capital

While locations in network structure may facilitate or hinder certain actions, network relationships serve important functions in facilitating the actions of individual actors; they form the basis of social capital (Lin, 1999). In previous studies on service utilization, it has been found that functional compared to structural components of networks have been more directly associated with service use (Knowlton, Hua, & Latkin, 2005). Lin (1999, 2002) defined social capital at the individual level in a clear and cogent manner and this study will follow this conceptualization. Therefore, social capital, for the purposes of this study, is defined as the resources embedded in social relationships; the access and use of which reside with actors, and the benefits are accrued to the individual actor and not the whole group (Lin, 2002). The use of the theory of social is especially appropriate because of the distinction it makes between “bonding social capital” and “bridging social capital” which helps distinguish between resources (instrumental and emotional) that are embedded in these youth’s street networks and resources outside of their street life (Putnam, 2000). More specifically, bonding social capital refers to people receiving resources from other people in the same social position (Putnam, 2000). In the case of homeless youth, this would mean that they are seeking help from other homeless youth who are also resource-poor (Stablein, 2011). These sources of social capital provide little opportunity for mobility or advantage (Irwin, LaGory, Ritchey, Fitzpatrick, 2008; Stablein, 2011). This underscores the argument previously made that social resources need not always be positive and might actually be restrictive (Lincoln, 2000). Bridging social capital on the other hand refers to resources that come from a more heterogeneous group of people and are usually more resourceful (Irwin et al., 2008). For homeless youth, these bridging ties can be caseworkers who can link them to much-needed services or their family and non-street friends who help them exit out of homelessness (Mitchell & LaGory, 2002). Based on social capital theory (Lin, 1999; Putnam, 2000), this study proposes that youth with more bridging social capital will be more likely to engage in employment services.

3.3. Social Influence

Another important pathway through which networks affect people’s behaviors, but is often ignored, is through social influence (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000). According to Marsden & Friedkin (1994), “the proximity of two actors in social networks is associated with the occurrence of interpersonal influence between the actors” (p. 3). Therefore, influence is not predicated on the deliberate attempt of one person to modify another person’s behavior (Berkman et al., 2000). Studies show that people mimic each other’s behavior, perhaps as a way of smoothing social interactions. The inclusion of social influence in the theoretical framework is necessary because it has been found that these processes of mutual influence occur separately from the provision of social resources taking place in the networks (Berkman et al., 2000). For example, cigarette smoking by peers is the best predictor of smoking among adolescents, irrespective of the resources that they receive from their networks. Similarly among homeless youth, De Rosa and colleagues (2001) found that homeless youth in Los Angeles were more likely to report testing for STDs than youth in San Diego. While, it was initially believed that this might be a result of the greater reach and number of HIV testing services in Los Angeles, in a later qualitative study, youth in Los Angeles indicated that it was more socially acceptable among their peers to be tested for HIV and STD’s (Rosa et al., 2001). Therefore, it is highly possible that these processes of social influence will extend to the use of employment services as well. Hence, one can posit that being connected to other youth who also utilize employment services will be associated with employment service utilization among this group of youth.

3.4. Research questions

Having made this distinction between network structure, function, and influence, the theoretical framework proposed suggests that by exploring the interplay between these three network dimensions, a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of social networks on utilization of employment services by homeless youth can be acquired. Therefore, guided by the proposed theoretical framework and prior empirical literature, this study addressed the following research questions:

RQ1. In general, what are the social-network factors associated with utilization of employment services among homeless youth?

RQ2. Are there relationships between the structural aspects of social networks and utilization of employment services?

RQ3. Are there relationships between social network functions (social capital) and network influence and utilization of employment services?

4. Methodology

4.1. Boundary Specification

Event Based Approach (EBA) (Freeman & Webster, 1994) was used to delineate the boundary of this sociometric network of homeless youth, who were all accessing services at a drop-in center in Los Angeles, CA. Network researchers acknowledge that in practice, the social world is composed of infinite sets of relations; however, it becomes necessary to impose certain constraints on who will be included in the sample (Wasserman & Galaskiewicz, 1994). While there are several ways to set such inclusion criteria, and no clear consensus exists, EBA is especially viable for sampling traditionally unbounded populations such as homeless youth. The EBA binds individuals into a social group based on a set of shared activities or events and is most relevant for runaway and homeless youth because of several reasons (Rice, Barman-Adhikari, Milburn & Monro, 2012). First, homeless youth are a transient and fluid population, and therefore, it is unrealistic to expect them to be listed in a formal membership list, a technique that is often used to delineate boundaries for social network studies, and is known as the positional approach (Marsden, 2005). Second, there are homeless youth who are often isolated from other homeless youth, therefore the relational approach (Marsden, 2005), which starts with an agency roster and then expands to include other people who are nominated by the existing sample, will exclude social isolates and other peripheral youth. The EBA approach is able to mitigate these limitations, because using this procedure, participants are sampled from “natural settings”, where people socialize, and entry, and exit is common. In the original study, this setting was a beach, and people who visited the beach three or more times in the previous month were designated as “regulars”. In this present study, youth who attended the agency one time in the prior month were included in the sample. Consistent with the EBA’s (Freeman and Webster, 1994) original criterion, drop-in-centers serve as natural settings where homeless youth routinely interact with each other and these interactions can be easily observed. Moreover, these spaces are relatively unregulated and entry and exit is common.

4.2. Sampling

An Event Based Approach (EBA) (Freeman & Webster, 1994) sample of 136 youth was recruited in 2008 in Los Angeles, California at one drop-in agency serving homeless youth. For inclusion, any youth, ages 13 through 24, was qualified to participate in the study, if they had received services at the agency on one prior occasion. The youth were recruited to participate in the study at the same time that they were signing up to receive services (e.g. a shower, clothing, and case management). Based on this procedure, only 14 youth declined to participate, yielding a refusal rate of only 9.3%. Signed voluntary informed consent was obtained from each youth, with the caveats that child abuse and suicidal and homicidal intentions would be reported. Informed consent was obtained from youth 18 years of age and older and informed assent was obtained from youth 13- to 17-years-old. The Institutional Review Board(IRB) waived parental consent, as homeless youth under 18 years are unaccompanied minors who may not have a parent or adult guardian from whom to obtain consent. Interviewers received approximately 40 hours of training, including lectures, role-playing, mock surveys, ethics training, and emergency procedures. Youth were reimbursed $20 for completing the survey. IRB approval was obtained from the University of (blinded for review).

4.3. Procedures

The survey consisted of two distinct parts: a computerized self-administered questionnaire with the option for an audio-assisted version and an interviewer-administered social network interview. A trained interviewer collected the network data from the participants using a face-to-face structured interview. Participants provided information on up to 10 people they had interacted with in the past 30 days. The participants were queried about the nature of these relationships, the kind of behaviors that these network contacts engage in, and the kind of resources that these people provided. Once the youth had finished nominating persons in their networks, attributes of each nomination were then collected, including, first name and last initial, aliases, age, gender, race/ethnicity, and whether the nominee was a client of the agency.

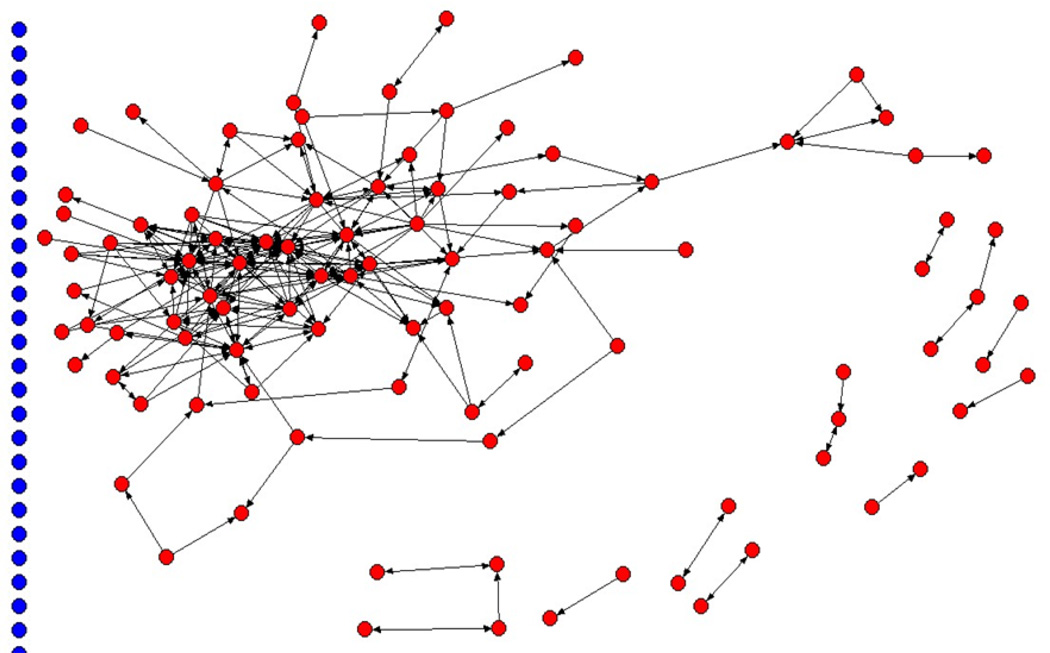

A sociomatrix was created linking participants in the sample. A sociomatrix is a tabular representation in matrix form of data collected (binary data in this case) using a sociometric method to measure interpersonal relationships. A directed tie from participant i to participant j was recorded if participant i nominated participant j in his/her personal network. Matches were based on name, alias, ethnicity, gender, approximate age, and agency attendance. If two distinct youth matched on all information, presence of a third common tie in each personal network was used to assign adjacency. Questionable matches were left un-coded (hence a conservative matrix of ties). Two research assistants each created independent adjacency matrices. The matrices were combined and discrepant ties dropped. Only 2 ties were discrepant (99.99% agreement across 18,360 possible ties). The resulting matrix has 288 directed ties (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sociometric network of homeless youth in Los Angeles, California (n=136). Blue circles are isolates. Arrows indicate direction of nominations between youth

Note: All 36 isolates not visible in figure.

An audio computer-administered self-interview (ACASI) survey was used to collect demographic and behavioral information. ACASI allows for participants to enter answers to questions privately into the computer, as they read questions silently on the computer screen and/or listen to the questions being read to them through headphones.

5. Predictor Variables

5.1. Individual level Variables

Demographic variables

Information on a number of socio-demographic variables was collected as a part of the larger study. For these particular analyses, youth’s age, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, time homeless, and housing situation were utilized. Single-item demographic variables represented age in years, gender (male vs. female) time homeless (more than two years versus less than two years), race/ethnicity (White vs. other), homelessness experience (literal homelessness vs. unstable housing), and sexual orientation (heterosexual vs. lesbian/gay/bisexual/unsure). Age was measured as a continuous variable; all other demographic variables were dummy coded with the first category listed above coded “1” and the remaining category as the reference group. Since there were only 3 youth who identified themselves as transgender, they were dropped from the final analyses. Also, since youth aged less than 15 cannot legally work in California, they were also dropped from the final analyses.

5.2. Social Network Variables

Network Structure

Position in network

Analysis of centrality measures such as K-cores and degree centrality were used to delineate the position of youth in the sociometric network. Centrality measures address the question, “Who is the most important or central person in this network?”A K-core is a maximal sub graph in which each point is adjacent to K other points; all the points in the K-core have a degree greater than or equal to K (Wasserman & Galaskiewicz, 1994). For example, in a network where everybody is connected to each other is the simplest form of component and has a 1 core. For this network, K-core 0 through 7 can be assigned. Periphery membership was defined by K-core 0 or 1 indicating that a youth either was an isolate or had only 1 tie to another network member. Degree centrality refers to the number of ties a node (or a person) has to other nodes (or persons) (Wasserman & Galaskiewicz, 1994). So, a person who has no connections will have zero degree centrality. In this sociometric network, degree centrality scores of 0 through 21 can be assigned. Based on these scores, youth who had less than 2 ties were regarded as peripheral to the network. All the network structural measures were dummy coded with youth in the periphery coded as “1” and the other category as the reference group.

Network Function

Social Capital

Respondents identified in the network interview which of their 10 alters could be counted on to lend them money, give them food, or give them a place to stay (instrumental support), and which alters these youth count on emotionally (emotional support) (Johnson et al., 2005). These measures of capturing source specific providers of emotional and instrumental support have been utilized and validated by previous studies (Johnson, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 2005; Rhoades et al., 2011; Wenzel et al., 2012).

Bonding social capital: Instrumental and emotional bonding capital were assessed separately by calculating the number of street- alters who are nominated as providers of emotional and instrumental resource (Johnson, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 2005). Using a count procedure, individual dichotomous measures were created indicating if the youth reported any street peers in their network whom they nominated as providers of emotional or instrumental support. Since the resulting distribution was skewed, these measures were included in analyses as binary indicators. The median is the preferred measure of determining a threshold for skewed measures (Wang, Fan, & Willson, 1996). A median split was used to dichotomize the amount of bonding social capital (instrumental and emotional) received from street relationships. Specifically, instrumental and emotional bonding social capital was dichotomized into high (greater than median) or low (lower than median or none) based on the median (Lovell, 2002).

Bridging social capital

Instrumental and emotional bridging capital were assessed separately by calculating the number of non-street alters who are nominated as providers of emotional and instrumental resource (Johnson et al., 2005). Using a count procedure, individual dichotomous measures were created indicating if the youth reported in their network specifically as being a parent, another family member, a significant other, a friend, a non-related adult, or a professional. Similar to the bonding social capital measure, these measures were also included in the analyses as binary indicator. A median split was used to dichotomize the amount of bridging social capital (instrumental and emotional) received from non-street relationships (such as parents, other family members, home-based friends, caseworkers). Specifically, instrumental and emotional bridging social capital dichotomized into high (greater than median) or low (lower than median or none) (Lovell, 2002). Due to the high correlation found between the instrumental and emotional resource measures for parents, and caseworkers, a composite measure was created to combine these two dichotomous indicators.

Network Influence

Employment service using alters

The number of employment service using alters were assessed by calculating the number of alters in the respondent’s sociometric network who also use employment services, and then dichotomizing it based on whether egos had alters who utilized services. Alters’ self-reports were used to determine whether youth were employment service users or not. Alters’ reports were used because these tend to be more accurate.

5.3. Outcome Variable

Use of employment services

The employment service program assessed in this study is one that is offered at the drop-in-center from which the participants were recruited. The agency provides comprehensive services to homeless youth and young adults including employment services. The curriculum includes résumé writing, mock interviews, and other pre-employment skills required for a successful job search. Egos were classified as “employment service” users if they indicated “yes” to the question: In the last 30 days, have you used employment services? This is a dichotomous level variable with “0” being never utilized and “1” indicating ever-utilized employment services within the past 30 days.

6. Data Analysis

6.1. Network Visualization

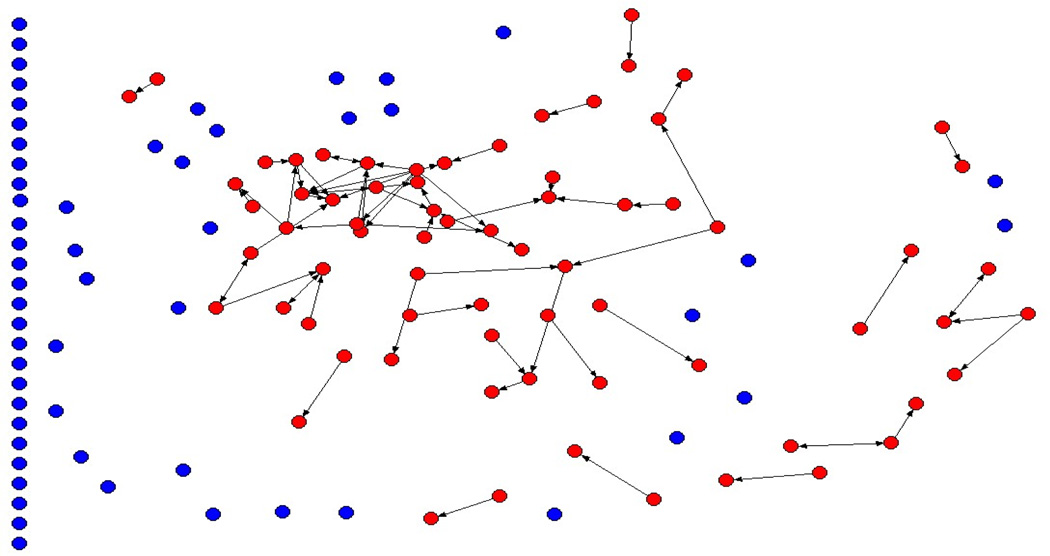

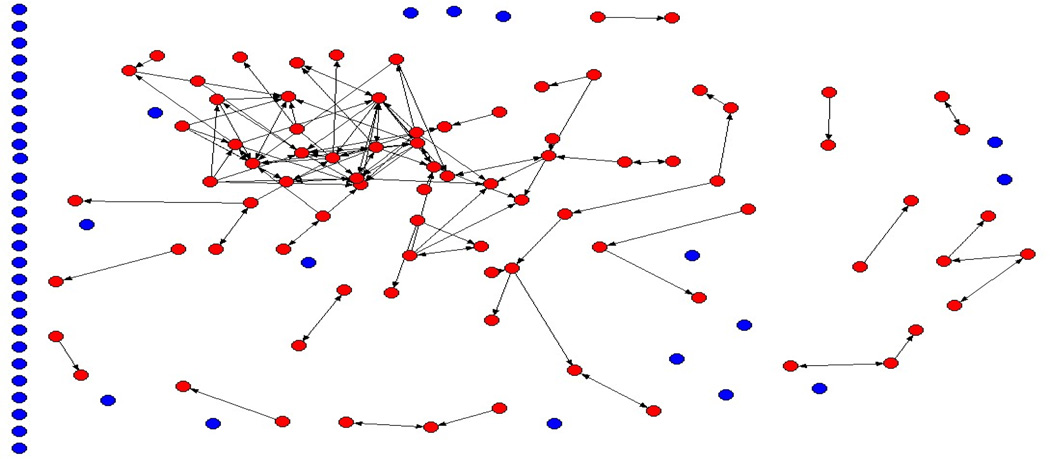

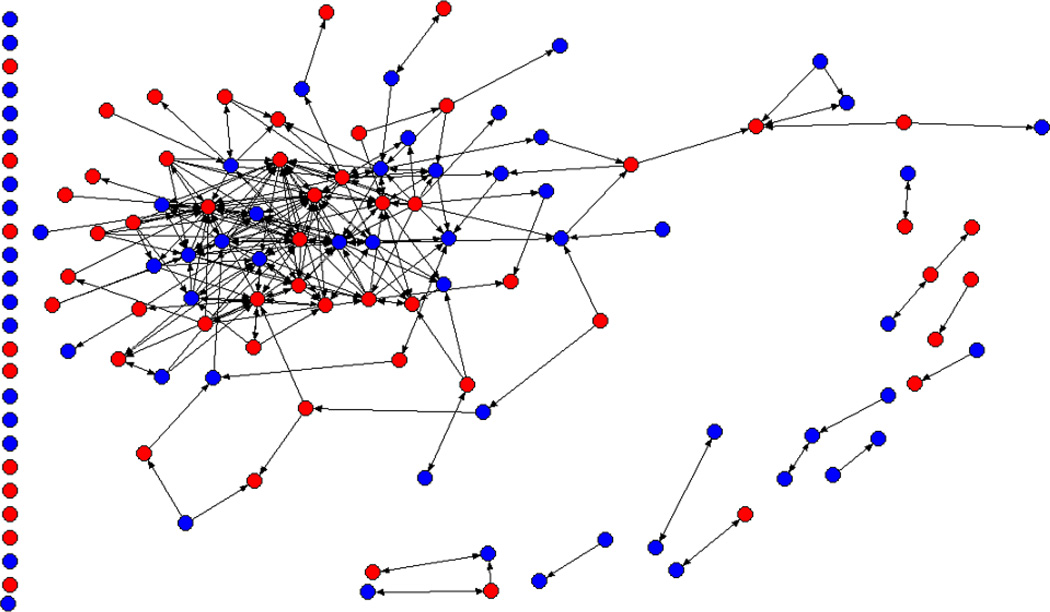

A common first step in network analysis is visualization. These diagrams are an excellent tool for pattern recognition. Netdraw 2.090 graph visualization software (Analytic Technologies, Irvine, CA) was used to generate network visualizations using the spring embedder routine. Spring embedders are based on the notion that the points may be thought of as pushing and pulling on one another. Two points that represent actors who are close will pull on each other, while those who are distant will push one another apart. Several algorithms have been developed that weight these pushes and pulls in different ways. However, they all seek to find an overall optimum in which there is least amount of stress on the springs connecting the whole set of points (Freeman, 2000). In this particular study, the visualizations generated were used to map the instrumental and emotional resource street networks (Figure 2 and Figure 3) and to understand visually whether there are positional attributes associated with the use of employment services in this network (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Instrumental Resource Street Network. Blue circles are isolates (n=65). Arrows indicate direction of nominations between youth. Note: All 65 isolates not visible in figure.

Figure 3.

Emotional Resource Street Network. Blue circles are isolates (n=53). Arrows indicate direction of nominations between youth. Note: All 53 isolates not visible in figure.

Figure 4.

Distribution of Employment Service Users in the Network. Red circles are employment service users (n=64). Arrows indicate direction of nominations between youth. Note: All isolates not visible in figure.

6.2. Network Analysis

UCINET (Analytic Technologies, Irvine, CA) was utilized to generate K-core assignments and centrality measures for the members in the sociometric network.

6.3. Statistical Analyses

Network analysis focuses on relationships and not on attributes. Therefore, network analysis violates the assumption of independence, which underlies linear statistical analysis. However, studies have recently started incorporating social network data into statistical modeling (Davey-Rothwell & Latkin, 2007; Flom et al., 2001; Friedman et al., 1997; Lovell, 2002; Rice et al., 2012). For these analyses, network level measures (i.e. K-core, degree centrality, and eigenvector centrality) were assigned to individuals as an attribute and included in the statistical models. The social network variables had sparse counts for certain categories of responses (given the small sample size) and therefore all the network variables were dichotomized.

The descriptive and multivariate data analysis for this paper was generated using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). In order to ensure statistical power and preserve degrees of freedom, a statistically accepted strategy (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000) was used to reduce the number of variables without compromising the comprehensiveness provided by the conceptual model. Therefore, the analyses predicting associations with employment services use proceeded in two stages. First, a series of bivariate logistic regressions were run to determine significant associations (p < .05) between the independent variables and employment services utilization. These bivariate associations were examined in a pair-wise approach, which is logically equivalent to the examination of a correlation matrix. Any independent variable that was found to be significantly associated (i.e., p <.10 level) with any dependent variable will be retained in the final multivariate logistic regression model (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000). Variance inflation factor (VIF) was checked to determine the potential multicollinearity among the independent variables.

7. Results

7.1 Descriptive Statistics

Socio-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 20.8 years (SD=2.1). There were slightly more males than females included in the sample. Most homeless youth were racial/ethnic minority youth. Fifty-six percent were literally homeless, and the rest were precariously housed, many “couch surfing” i.e. temporarily staying with friends or relatives. A majority of the youth had spent more than two years homeless. Regarding use of employment services (which is the outcome variable), a little less than half of the sample (47.4%) reported engaging in employment services within the past 30 days of the data being collected.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Homeless Youth (n=136): Los Angeles, CA, 2008

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 50 | 37.5 |

| Male | 81 | 60.5 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay, Lesbian or Bisexual | 17 | 12.5 |

| Heterosexual | 116 | 87.2 |

| Time Homeless | ||

| Homeless 2+ Years | 90 | 66.2 |

| Homeless < 2 years | 46 | 33.8 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 48 | 38.1 |

| Latino | 31 | 24.6 |

| White | 27 | 21.4 |

| Mixed race/other | 20 | 15.9 |

| Current Living Situation | ||

| Literal Homelessness | ||

| Street | 42 | 31.1 |

| Shelter | 24 | 17.8 |

| Hotel, Motel | 10 | 7.4 |

| Temporary Housing or couch surfing | 60 | 43.7 |

| Mean | SD | |

| Age | 20.8 | 2.1 |

| Use of Employment Services | No. | % |

| No | 72 | 52.5 |

| Yes | 64 | 47.4 |

7.2. Network Characteristics

Network characteristics are presented in Table 2. More than two-thirds (67.2%) of the network had less than two ties, and more than half (56.6%) of the network were in Kcores 0 through 1. A majority of the youth reported receiving high amount of bridging capital from a number of sources, with a large percentage of them reporting receiving both instrumental and emotional resources from extended family members, followed by home-based friends, and parents. Youth also reported receiving greater emotional bonding capital than instrumental bonding capital from street-peers. Concerning network influence, a little more than one-third (36.5%) of the youth reported having any employment service using alters in their network.

Table 2.

Social Network Characteristics of Homeless Youth (n=136): Los Angeles, CA, 2008

| Network Structure |

n |

% |

|---|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | ||

| Degrees 0–2 | 92 | 67.2 |

| Degrees 3–21 | 44 | 32.8 |

| K-core | ||

| Kcore 0–1 | 77 | 56.6 |

| Kcore 2–7 | 59 | 43.4 |

|

Network Function |

||

| Bridging Capital | ||

| Instrumental | ||

| High capital | ||

| Parents | 58 | 42.34 |

| Family | 75 | 54.74 |

| Sibling | 26 | 19.67 |

| Home-based Friends | 70 | 51.09 |

| Caseworkers | 27 | 19 |

| Emotional | ||

| High Capital | ||

| Parents | 57 | 41.61 |

| Family | 100 | 72.99 |

| Sibling | 27 | 19.71 |

| Home-based Friends | 90 | 65.69 |

| Caseworkers | 26 | 18.98 |

| Bonding Capital | ||

| Instrumental | ||

| High Capital | ||

| Street Peers | 62 | 45.26 |

| Emotional | ||

| High capital | ||

| Street Peers | 85 | 62.5 |

|

Network Influence |

||

| Employment service alters | ||

| None | 86 | 63.5 |

| Any | 50 | 36.5 |

7.3. Network Visualization

As mentioned above, one of the first steps in network analysis is visualization. Figure 1 represents the sociometric network of 136 homeless youth. Small numbers of ties aggregate into larger network structures of homeless youth. Visual inspection of this network reveals a core, periphery, and a large number of isolates. Figures 2 and 3 represent the instrumental and emotional resource networks (bonding capital) of homeless youth. Visual examination of these network structures reveals that these two network structures look markedly different from the original network (Figure 1). In particular, the number of isolates increases in both the instrumental (n=65) and emotional networks (n=53) indicating that even though youth might be connected, they might not be relying on these street-peers for resources. Figure 4 depicts the spatial distribution of employment service users in the network. On inspecting the network, no visible structural pattern of employment service use could be detected in the network, as youth who engage in employment services are uniformly distributed through the various regions of the network.

7.4. Bivariate and Multivariate Analyses

Table 3 presents results of the bivariate associations and multivariate associations among independent and dependent variables. Among the bivariate associations, age, sexuality, ethnicity, network structure, resources received from parents, and family members (both instrumental and emotional), and employment using alters were not significantly associated with employment service use and these variables were dropped from the multivariate model.

Table 3.

Bivariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression of Employment Service Use among Homeless Youth in Los Angeles, California (n=133)

| Bivariate Analyses |

Multivariate Analyses |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR |

95 % CI |

OR |

95 % CI |

|||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age | 1.01 | 0.92 | 1.10 | |||||

| Gender (Male=1) | 1.89 | 0.84 | 4.24 | |||||

| Race (White=1) | 0.71 | 0.27 | 1.88 | |||||

| Sexuality (LGBT=1) | ||||||||

| Housing (Temporary Housing=1) | 2.53 | 1.13 | 5.63 | * | 2.44 | 1.09 | 5.46 | * |

| Time since first homeless | 1.25 | 1.03 | 1.53 | * | 1.03 | 0.94 | 1.13 | |

| Structure | ||||||||

| Kcore (Kcore 0–1=1) | 1.62 | 0.80 | 3.29 | |||||

| Degree Centrality (Deg 3–7=1) | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.12 | |||||

| Function (High Resource=1) | ||||||||

| Caseworkers (Any resource) | 2.33 | 1.05 | 5.17 | * | 2.95 | 1.00 | 8.67 | * |

| Parents (Any resource) | 1.02 | 0.31 | 3.41 | |||||

| Family (Instrumental) | 2.00 | 0.90 | 4.44 | |||||

| Family (Emotional) | 1.08 | 0.45 | 2.60 | |||||

| Home-based peers (Instrumental) | 2.54 | 1.138 | 5.668 | * | 4.17 | 1.05 | 16.60 | * |

| Home-based peers (Emotional) | 2.84 | 1.25 | 6.44 | ** | 6.40 | 1.69 | 24.23 | ** |

| Street Peers (Instrumental) | 2.24 | 1.23 | 4.75 | * | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.68 | * |

| Street Peers (Emotional) | 2.77 | 1.24 | 6.22 | ** | 6.40 | 1.69 | 24.23 | ** |

| Influence | ||||||||

| Service using alters (High=1) | 1.24 | 0.62 | 2.50 | |||||

| −2 Log Likelihood | 143.24 | |||||||

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

P < .05;

P < .01.

In the multivariate model, housing status, receiving bridging capital from home-based friends, and caseworkers, and receiving bonding capital from street peers were all significantly associated with the use of employment services. Specifically, youth who are in some form of temporary housing were 2.4 times more likely to use employment services than youth who were literally homeless. Youth who reported receiving instrumental resources from home-based friends were 4 times more likely to engage in employment services than youth who did not. Youth who reported receiving any instrumental or emotional resources from caseworkers were 2.9 times more likely to engage in employment services than youth who did not. Youth who reported receiving instrumental resources from street-peers were 86 percent less likely to use employment services than youth who did not. Finally, youth who reported receiving emotional resources from street-peers were 6.4 times more likely to use employment services than youth who did not.

8. Discussion

To date, little research has explored utilization of employment services and its relationship to social network factors among homeless youth. This study is especially important because it not only adds to the limited research on social network factors associated with service use among homeless youth, but is the first study which has utilized both egocentric and sociometric methods to identify a range of network dimensions (both structural and functional) which has not been attempted in the past . The study findings provide some preliminary empirical evidence for the proposed theoretical framework, and highlight the role of the social context in understanding the use of employment services in this population. In addition to the theoretical contributions of this study, several important empirical findings emerge from this analysis.

It was encouraging to see that almost half of youth (47.3%) who participated in the study utilized employment services offered at the agency. Studies have generally found that youth are more likely to use services that fulfill their basic needs (such as drop-in centers) relative to services that provide counseling, or skill-building services (De Rosa et al., 1999; Pergamit et al., 2010; Sweat et al., 2008). However, the high participation rates in this study perhaps demonstrate the viability of drop-in-centers as potential venues through which employment services can be offered. Research finds that a number of homeless youth are reluctant to engage in services because of the fragmentation of services and barriers in accessing these services (Pergamit et al., 2010). Drop-in-centers can therefore operate as one stop shops where such services can be delivered.

More importantly, our results suggest that the social context that these youth find themselves embedded in is vital to understanding whether they engage in employment services. It is especially important to note that very few of the individual level variables were significantly associated with the use of employment services which supports the need to conduct studies which shed further light on aspects of the social environment which might explain these decisions better and inform service planning.

The study findings suggest that social capital is more significant in understanding why homeless youth use employment services, relative to network structure and network influence. This is consistent with previous research, which has found that functional compared to structural components of networks are more directly associated with service use (Thoits, 1992; Albert, Becker, Mccrone, & Thornicroft, 1998; Knowlton et al., 2005). However, one recently conducted study found that homeless youth who are shelter users tend to cluster together, i.e. youth who use shelters are more likely to nominate youth who also use shelters (Chew Ng et al., 2013). Therefore, while social capital was found to a more significant correlate of employment services in this study, one cannot fully discount the role of network influence either. Further, longitudinal and ethnographic work is needed to understand the nature of such social influence processes.

As the social capital theory suggests, the findings highlight how social capital can be both positive and negative; and lend credence for the need to distinguish between forms of resources (instrumental and emotional) and specific sources of these resources (bridging/non-street and bonding/street relationships). In particular, bonding social capital was found to have differential effects on use of employment services among this population. The study found that while the receipt of instrumental resource from street-peers was associated with a decreased likelihood of engaging in employment services, receiving emotional resources from street-peers increased the likelihood of engaging in employment services. This paradoxical effect of engagement with street peers has also been illustrated in another study (Bao, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 2000). Bao and colleagues (2000) reported that while emotional support from street peers reduced depressive symptoms, the receipt of instrumental support from street-peers was associated with an increase in these symptoms. It is possible that receipt of instrumental resources from street peers is associated with a greater dependence on the street economy (Whitbeck, 2009; Ferguson, Bender, Thompson, Xie, & Pollio, 2011). Additionally, such dependence could also signify a lack of attachment to more conventional sources of support, and indicate a greater disaffiliation and marginalization from mainstream society.

Consistent with previous studies, the youth in this study reported receiving bridging social capital from a number of sources such as parents, siblings, extended family, home-based peers, and caseworkers (Johnson, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 2005; Rice, Stein, & Milburn, 2008; Whitbeck, 2009). However, except for home-based peers and caseworkers, receiving bridging capital from other relationships was not significantly associated with the use of employment services. Specifically, youth who reported receiving instrumental resources from home-based peers and any resource from caseworkers were more likely to use employment services relative to youth who did not. Peer social networks become more relevant for youth during adolescence; this might be especially true for homeless youth who report having fractured relationships with their family members (Whitbeck, 2009). Home-based peers might facilitate prosocial skills (such as the use of employment services) in these youth by serving as role models for homeless youth in identifying important milestones in their lives (Rice, Milburn, & Monro, 2011). Beyond peers, caseworkers are also vital resource mechanisms for some homeless youth, and often fulfill the role of a supportive adult mentor (Paradise & Cauce, 2002). Studies have consistently demonstrated the protective nature of a dedicated and concerned adult in the lives of these young people (Cauce et al., 2000; de Winter & Noom, 2003; McGrath & Pistrang, 2007).

The null relationship between network position and employment service use is likely a function of the resources that these youth receive from non-street members, which changes the configuration of the network. For example, if one compares the original network-structure of the 136 homeless youth in the study in Figure 1 to Figure 3 where only sources of instrumental help from street peers are depicted, one can see that the network structure is significantly changed. The greater number of isolates in the instrumental street network might indicate their reliance on non-street members for material assistance, and reflect a more conventional form of socialization (Whitbeck, 2009). This also confirms previous research, which has found that relationships that provide resources are more influential to help seeking than those, which are primarily a source of sociability (Pescosolido, 1992).

Finally, another notable finding that emerged out of this study is the association between housing status and utilization of employment services. Youth who were literally homeless were less likely to look for employment services than youth who were in some form of temporary housing. This supports results from other studies which have found that severity of homelessness is not only related to service use, but also to other risk behaviors (Chew-Ng et al., 2013; Tyler et al., 2012). It is well known that a homeless individual’s first and primary need is to obtain stable housing and that once this need is fulfilled, then the individual is more likely to engage in other services that that help them regain stability (Stenfancic & Tsemberis, 2007). Therefore, it is possible that youth who are literally homeless are still struggling to meet their immediate needs, and finding employment is not on the top of their priority list.

8.1. Study Strengths and Limitations

As is the case with any study, the findings need to be interpreted in light of the limitations of the study. First, this study was based on cross-sectional data, and therefore does not allow for causal interpretations. It is entirely possible that youth were reaching out for resources from more prosocial network members such as caseworkers and home-based friends, because of their involvement with employment services and not vice-versa. Longitudinal research is needed to examine how network dynamics operate over time in order to understand the causal pathway through which network attributes affect the use of employment services in this population. Second, the way in which social capital was measured in this study was relatively crude. However, there has been no consensus on the best way in which social capital should be measured; no validated instrument has yet been designed (MacGillivray & Walker 2000; Popay 2000). It has been suggested that measures of social capital should be thoroughly based on, and tied to, the conceptual framework for the specific study (Cavaye, 2004). The measures of social capital in this study follow Lin’s (1999) conceptualization of social capital, which has been previously defined. Third, even though it was assumed that the receipt of instrumental resource from street youth could imply an involvement in the street economy, the data cannot support this assumption, as this information was not collected. However, previous studies have reported high levels of illegal street survival strategies among homeless youth (Kipke et al., 1997; Whitbeck, 2009; Ferguson et al., 2011). Fourth, these data came from only one agency, and even though drop-in centers are relatively barrier-free environments which attract a diverse group of homeless youth (Karabanow & Clement, 2004) it is likely that some street-youth, especially ones who are most high-risk were left out. Therefore, these findings might not be generalizable to the broader population of homeless youth. Also, it is important to note that employment services as assessed in the study is not an evidence-based practice and the curriculum is loosely structured. There is no data on the efficacy or the effectiveness of the program, which might have affected participation rates. Last, but not the least, we acknowledge that given our restricted sample size, and pre-existing variables, which were collected as a part of a larger study, we had to limit the focus of our analyses to a finite set of variables that were most pertinent to the aims of this study. A future study could remediate this limitation by collecting data from a larger population of homeless youth.

8.2. Implications for policy, practice, and future research

Although this study is exploratory, the results from this study provide specific directions for interventions aimed to increase use of employment services among homeless youth. The findings indicate that the resources received from relationships (or social capital) are crucial in understanding the utilization of employment services in this population. In particular, the study illustrates the beneficial effects of receiving instrumental resources from non-street relationships, especially from their home-based peers. These results suggest that interventions that promote connections with non-street relationships might facilitate engagement in employment services in this population. Currently, there is a dearth of empirically tested interventions to increase service use among homeless youth. However, one particular intervention with homeless youth in Los Angeles, California, which aimed to increase positive social relationships and consequently, greater engagement in services, has reported encouraging outcomes (Ferguson & Xie, 2007).

This study also found that receiving instrumental resources from street peers acts as a deterrent for the use of employment services within this group. This underscores the need for two approaches to potentially combat this problem. First, these youth might be highly enmeshed in the street culture; therefore, interventions which focus on building trust and reciprocity with these youth might be more effective (Kipke et al., 1997). Second, from a policy standpoint, this suggests the need for concerted efforts to reduce homeless youth’s reliance on the street economy in meeting their day-to-day needs. Previous research has found that programs, which meet homeless youth’s immediate needs first and then assist them with addressing other aspects of their lives, have had success in helping them regain stability (Robertson, 1996). This is also evidenced by this current study, which found that youth who had relatively stable housing were more likely to use employment services.

However, this does not imply that long-term management and follow-up should be ignored. Most services for homeless youth are emergency or short-term, with care limited to crisis periods, which greatly reduces their ability to engage these youth (Robertson & Toro, 1999). In previous studies, long-term case management provided by a supportive adult (such as a caseworker) has been found to be associated with improvements in physical, psychological, and social outcomes for homeless youth (Cauce et al., 1994; Cauce et al., 2000; Paradise & Cauce, 2002). Therefore, caseworkers should be encouraged to maintain an open channel of communication, and try to be as accessible to these youth as they can.

Finally, this paper took an important step toward future research on service engagement among homeless youth by proposing a theoretical framework that considers the multidimensionality of network phenomena. The utility of this theoretical framework will be appraised by its ability to provide guidance to researchers to study the network components of service use and identify network features that can be modified to enhance use of employment services among homeless youth.

HIGHLIGHTS.

We developed an integrative social network theory to explain the use of services among homeless youth.

Bonding and bridging social capital were found to have differential effects on use of employment services.

Youth receiving social resources from home-based peers and case managers were more involved in employment services.

Interventions that promote connections with non-street relationships might facilitate engagement in employment services.

Biographies

ERIC RICE joined the USC School of Social Work faculty in 2009. He is an expert in social network theory, social network analysis, and the application of social network methods to HIV prevention research.

Rice is committed to community-based participatory research. Rice has an interest in conducting work on HIV prevention with high risk adolescent populations. He has worked closely with many community-based organizations over the past seven years, working primarily on issues of HIV prevention for homeless youth and impoverished families affected by HIV/AIDS. Rice has served as an external reviewer for Los Angeles County’s Office of AIDS Programs and Policy and has conducted program evaluation and consultation with organizations working with homeless youth and high risk adolescents.

Anamika Barman-Adhikari, PhD is an Assistant Professor at the School of Social Work at California State University, Fresno.

Dr. Barman-Adhikari’s experiences in policy, research, and clinical services have coalesced in her current research goals and agenda. These experiences have collectively helped me to formulate a research agenda, which is devoted to the prevention of HIV and substance use among high-risk youth and other vulnerable populations. Her research interests are broadly centered on understanding the social-contextual determinants of risk behaviors among vulnerable youth populations such as homeless and minority youth. Utilizing an ecological approach, her work aims to assess how family, peers, community and the society at large define the contexts within which vulnerable youth function and how these contexts help to explicate the patterns of risk behaviors that these youth engage in. The goal of her research is to create prevention interventions that acknowledge these contextual environments and utilize “social network methodology” to determine how these new ideas can be disseminated and sustained using a “community based participatory research approach”.

She is a member of the Society for Social Work and Research, the Society for Prevention Research, and the American Public Health Association. Dr. Barman-Adhikari serves as a reviewer for the American Journal of Public Health, the Journal of Medical Internet Research, Journal of LGBT Youth, and the Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services. Dr. Barman-Adhikari has published in the Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, American Journal of Public Health, Journal of Adolescent Health, and Journal of Family Issues, among other journals. Her teaching interests include social work research, statistics, and theories of human behavior and social environment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albert M, Becker T, Mccrone P, Thornicroft G. Social networks and mental health service utilization-a literature review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1998;44(4):248–266. doi: 10.1177/002076409804400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M. Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1986;14(4):413–445. [Google Scholar]

- Bao WN, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Abuse, support, and depression among homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000:408–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdahl TA, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB. Predictors of first mental health service utilization among homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37(2):145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51(6):843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP, Halgin DS. On Network Theory. Organization Science. 2011;22(5):1168–1181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0641. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead W, Gehlbach SH, DeGruy FV, Kaplan BH. Functional versus structural social support and health care utilization in a family medicine outpatient practice. Medical Care. 1989:221–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier N, White D. Cohesion of the primary social network and sustained service use before the first psychiatric hospitalization. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2002;29(4):404–418. doi: 10.1007/BF02287347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson JL, Sugano E, Millstein SG, Auerswald CL. Service utilization and the life cycle of youth homelessness. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(5):624–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaye J. Social capital: a commentary on issues, understanding, and measurement. Vol. 27 Melbourne: Observatory PASCAL; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Morgan CJ, Wagner V, Moore E, Sy J, Wurbacher K, Weeden K, Tomlin S, Blanchard T. Effectiveness of intensive case management for homeless adolescents: Results of a 3-month follow-up. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 1994;2:219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Paradise M, Ginzler JA, Embry L, Morgan CJ, Lohr Y, Theofelis J. The characteristics and mental health of homeless adolescents’ age and gender differences. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2000;8(4):230–239. [Google Scholar]

- Chew Ng RA, Muth SQ, Auerswald CL. Impact of Social Network Characteristics on Shelter Use Among Street Youth in San Francisco. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53(3):381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran BN, Stewart AJ, Ginzler JA, Cauce AM. Challenges faced by homeless sexual minorities: Comparison of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender homeless adolescents with their heterosexual counterparts. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(5):773–777. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky AL, Lee JAS, Raap M, Hall C. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at ages 23 and 24. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Terao S, Bost N. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Conditions of youth preparing to leave state care. Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Davey-Rothwell MA, Latkin CA. HIV-related communication and perceived norms: An analysis of the connection among injection drug users. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2007;19(4):298–309. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.4.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa CJ, Montgomery SB, Kipke MD, Iverson E, Ma JL, Unger JB. Service utilization among homeless and runaway youth in Los Angeles, California: Rates and reasons. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24(3):190–200. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Winter M, Noom M. Someone who treats you as an ordinary human being…homeless youth examine the quality of professional care. British Journal of Social Work. 2003;33(3):325–338. [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients' adherence to medical recommendations: A quantitative review of 50 years of research. Medical Care. 2004;42(3):200–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE. Peer group structure and adolescent cigarette smoking: A social network analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993:226–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson K, Xie B. Feasibility study of the Social Enterprise Intervention with homeless youth. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007;18(1):5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KM, Xie B, Glynn S. Child & Youth Care Forum. No. 3. Vol. 41. US: Springer; 2012. Jun, Adapting the individual placement and support model with homeless young adults; pp. 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KM, Bender K, Thompson S, Xie B, Pollio D. Correlates of Street-Survival behaviors in homeless young adults in four US cities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(3):401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KM, Bender K, Thompson SJ, Maccio EM, Pollio D. Employment Status and Income Generation Among Homeless Young Adults Results From a Five-City, Mixed-Methods Study. Youth & Society. 2012;44(3):385–407. [Google Scholar]

- Flom PL, Friedman SR, Kottiri BJ, Neaigus A, Curtis R, Des Jarlais DC, Zenilman JM. Stigmatized drug use, sexual partner concurrency, and other sex risk network and behavior characteristics of 18-to 24-year-old youth in a high-risk neighborhood. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2001;28(10):598–607. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman LC, Webster CM. Interpersonal proximity in social and cognitive space. Social Cognition. 1994;12(3):223–247. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Neaigus A, Jose B, Curtis R, Goldstein M, Ildefonso G, Des Jarlais DC. Sociometric risk networks and risk for HIV infection. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(8):1289–1296. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.8.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Lau AS, Yeh M, McCabe KM, Hough RL, Landsverk JA. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1336–1343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett SB, Higa DH, Phares MM, Peterson PL, Wells EA, Baer JS. Homeless youths' perceptions of services and transitions to stable housing. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2008;31(4):436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geber GM. Barriers to health care for street youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;21(5):287–290. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber MG, Toro PA. Homelessness among families, children, and adolescents: An ecological–developmental perspective. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7(3):123–164. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000045124.09503.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook JL, Courtney ME. Employment outcomes of former foster youth as young adults: The importance of human, personal, and social capital. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(10):1855–1865. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression Wiley-Interscience. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Irwin J, LaGory M, Ritchey F, Fitzpatrick K. Social assets and mental distress among the homeless: Exploring the roles of social support and other forms of social capital on depression. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(12):1935–1943. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KD, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Predictors of social network composition among homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28(2):231–248. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabanow J, Clement P. Interventions with street youth: A commentary on the practice-based research literature. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2004;4(1):93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Montgomery SB, Simon TR, Iverson EF. “Substance abuse” disorders among runaway and homeless youth. Substance Use & Misuse. 1997;32(7–8):969–986. doi: 10.3109/10826089709055866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Unger JB, O’Connor S, Palmer RF, Lafrance SR. Street youth, their peer group affiliation, and differences according to residential status, subsistence patterns, and use of services. Adolescence. 1997;32(127):655–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein JD, Woods AH, Wilson KM, Prospero M, Greene J, Ringwalt C. Homeless and runaway youths' access to health care. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27(5):331–339. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton A, Hua W, Latkin C. Social support networks and medical service use among HIV-positive injection drug users: Implications to intervention. AIDS Care. 2005;17(4):479–492. doi: 10.1080/0954012051233131314349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz PD, Lindsey EW, Jarvis S, Nackerud L. How runaway and homeless youth navigate troubled waters: The role of formal and informal helpers. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2000;17(5):381–402. [Google Scholar]

- Latkin C, Knowlton A. Micro-social structural approaches to HIV prevention: A social ecological perspective. AIDS Care. 2005;17(S1):102–113. doi: 10.1080/09540120500121185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Forman V, Knowlton A, Sherman S. Norms, social networks, and HIV-related risk behaviors among urban disadvantaged drug users. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(3):465–476. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz-Rashid S. Employment experiences of homeless young adults: Are they different for youth with a history of foster care? Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28(3):235–259. [Google Scholar]

- Lin N. Building a network theory of social capital. Connections. 1999;22(1):28–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lin N. Social capital: A theory of social structure and action. Cambridge Univ Pr.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD. Social support, negative social interactions, and psychological well-being. Social Service Review. 2000;74(2):231–252. doi: 10.1086/514478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. Leading the way: Creating solutions to homelessness in LA Annual Report 2010–2011. 2010–2011 Retrieved January 3rd from http://documents.lahsa.org/Communication/WebDocuments/flipbook/LAHSA_Annual_Report_2010-2011/lahsa-AR-2010-11.html#/1/zoomed.

- Lovell AM. Risking risk: The influence of types of capital and social networks on the injection practices of drug users. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(5):803–821. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillivray A, Walker P. Local social capital: Making it work on the ground. In: Baron S, Field J, Schuller T, editors. Social capital: Critical perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden PV. Recent developments in network measurement. Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis. 2005;8:30. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden PV, Friedkin NE. Network studies of social influence. SAGE FOCUS EDITIONS. 1994;171:3–3. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath L, Pistrang N. Policeman or friend? Dilemmas in working with homeless young people in the United Kingdom. Journal of Social Issues. 2007;63:589–606. [Google Scholar]

- Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Rice E, Mallet S, Rosenthal D. Cross-national variations in behavioral profiles among homeless youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;37(1–2):63–76. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-9005-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CU, LaGory M. Social capital and mental distress in an impoverished community. City & Community. 2002;1(2):199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Paradise M, Cauce AM. Home Street home: The interpersonal dimensions of adolescent homelessness. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. 2002;2(1):223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Pergamit MR, Ernst M, Hall C. Runaway youth’s knowledge and access of services. Chicago IL: National Runaway Switchboard; 2010. Available at http://www.800runaway.org/media/documents/NORC_Final_Report_4_22_10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA. Beyond rational choice: The social dynamics of how people seek help. American Journal of Sociology. 1992:1096–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Popay J. Social capital: The role of narrative and historical research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2000;54:401–401. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.6.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Raleigh-DuRoff C. Factors that influence homeless adolescents to leave or stay living on the street. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2004;21(6):561–571. [Google Scholar]

- Reid P, Klee H. Young homeless people and service provision. Health & Social Care in the Community. 1999;7(1):17–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.1999.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades H, Wenzel SL, Golinelli D, Tucker JS, Kennedy DP, Green HD, Zhou A. The social context of homeless men's substance use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118(2):320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice E, Stein JA, Milburn N. Countervailing social network influences on problem behaviors among homeless youth. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31(5):625–639. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice E, Milburn NG, Monro W. Social networking technology, social network composition, and reductions in substance use among homeless adolescents. Prevention Science. 2011;12(1):80–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0191-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]