Abstract

A man presenting in his 50s, following conviction for a non-violent crime, to forensic psychiatric services, and then to a neuropsychiatry service with an unusual presentation of psychosis: second person auditory hallucinations, grandiose delusions and somatic delusions. Detailed collateral and family history revealed a background of progressive cognitive deficit and a family history of motor neuron disease. MRI of the brain revealed asymmetrical parieto-occipital volume loss and genetic testing demonstrated a pathogenic expansion of the chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9ORF72) gene consistent with familial frontotemporal dementia caused by a hexanucleotide repeat expansion at C9ORF72, a recently discovered cause of familial frontotemporal dementia/motor neuron disease. This form of frontotemporal dementia should be considered as an important potential differential diagnosis for patients presenting with psychotic symptoms in later life, in whom a detailed family history and thorough cognitive assessment is essential.

Background

There is a broad differential diagnosis for patients presenting with psychotic symptoms, encompassing primary psychiatric illness, effects of toxic drugs, infectious processes, metabolic diseases, epilepsy and neurodegenerative disorders. Psychotic symptoms are common in patients with Alzheimer's dementia.1 2 In the frontotemporal dementia (FTD) spectrum, psychotic symptoms have probably been under-recognised3 and may signal particular pathologies: in particular, FTD and motor neuron disease (MND) associated with mutations in the recently identified chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9ORF72) gene.4

We report a case of a man presenting in a forensic psychiatry setting with psychotic symptoms caused by a pathological expansion in the C9ORF72 gene.

Case presentation

The patient is a man who presented while in his 50 s, convicted for a non-violent crime. While being conveyed to the prison following an appeal against this conviction, he began to report psychotic experiences. He described hearing the voice of God in his ear telling him that his appeal against the conviction had been successful and later claimed that he was telepathic. He was transferred from prison to a forensic psychiatry unit for a 7-month period of assessment.

The only relevant medical history was poorly controlled hypertension and there was no history of psychiatric disease or alcohol or drug misuse. He made no effort to conceal the crimes for which he was convicted and had a brief incarceration for a similar crime less than 1 year previously. He was married with children and there was no known family history of psychiatric or cognitive disease. There was, however, a family history of MND, with one of the patient's five siblings—an older brother—manifesting symptoms of the condition in his mid-50s before developing swallowing and speech problems and dying from respiratory complications at around 60 years of age. He is not known to have had any cognitive problems.

At no point did he report affective symptoms or cognitive impairment, but he suffered from a number of apparent psychotic symptoms. He continued to report intermittently that he could hear the voice of God in his ear, reassuring him by offering a letter which would overturn his conviction, and he would be seen overtly responding to this auditory hallucination. He planned to go to Cyprus, where he believed he would become president. He also described mild intermittent headaches, which he attributed variously to God and to the courts who, he believed, had been corrupt and prejudiced against him. In addition, he described having a ‘small man’ in his bowel who helped with his digestion.

These symptoms fluctuated in intensity, seemingly worse when called to repeat court appearances, and he did not seem distressed by them; this, combined with performance on a neuropsychometric test for malingering worse than expected by chance, led to some suspicion of malingering. Sulpiride and aripiprazole were trialled but there was little response to these.

Problems with his cognition—naming problems—were detected more than 12 months after the onset of psychotic symptoms and he was referred to a specialist neuropsychiatry service. Collateral history was obtained from his wife, who had noted changes over the preceding 5 years with reduced empathy, increased appetite for sweet foods and irritability. She also reported that he had developed a fixed routine from which he had difficulty deviating and had begun to use a satellite-navigation system to guide him when on familiar routes. His short-term and long-term episodic memory, language ability and numeracy skills seemed unchanged. In addition, his wife explained that he had developed a new religious preoccupation.

On mental state examination, he presented as reasonably kempt and casually dressed. He made good eye contact and allowed the establishment of a superficially friendly but limited rapport. Although he seemed disorganised and perplexed on approach, he was not anxious or distressed, and his speech was tangential and pressured. His mood was subjectively and objectively euthymic and there were no biological symptoms of depression though his affect was flat. He responded overtly throughout the interview to apparent auditory hallucinations and described hearing the voice of God in his ear, and he also possessed delusional beliefs about his conviction and having a man in his bowel who aided digestion. He lacked any insight into the abnormal nature of these experiences.

Neurological examination revealed no cranial or peripheral nerve deficit. There was a positive pout reflex but other primitive reflexes were absent. Cognitive examination demonstrated frontal lobe deficits—inability to complete the Luria three-step task or alternating hand movements and difficulty in interpreting proverbs. He had difficulty in naming items but his reading was normal and there was no significant episodic memory impairment. Parietal lobe testing demonstrated mild difficulty in copying hand gestures and slowness in recognising degraded pictures and letters but no ideomotor apraxia or difficulties with arithmetic.

Investigations

Routine blood tests to look for common causes of cognitive impairment and psychosis, including thyroid function, calcium, vitamin B12 and folate were normal. HIV, syphilis antibodies and Whipple’s PCR were negative and a screen of autoimmune causes of psychosis—anti-nuclear antibody, anti-neurophil cytoplasmic antibody, anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibody, antiglycine, N-methyl-D-aspartate--receptor antibody and voltage-gated potassium channel antibody—revealed no abnormality.

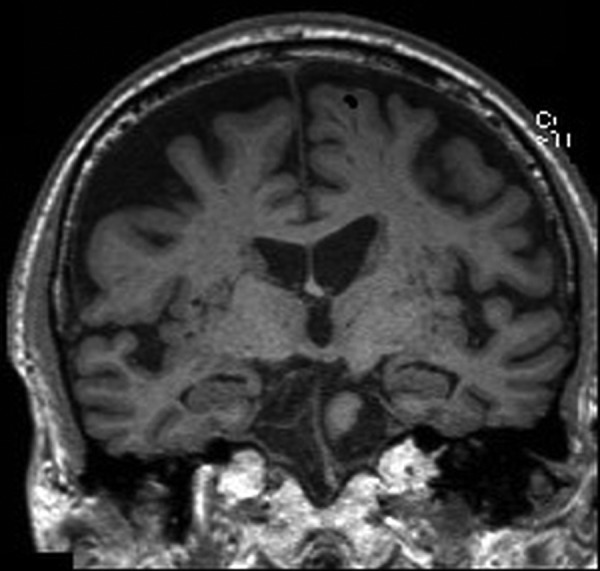

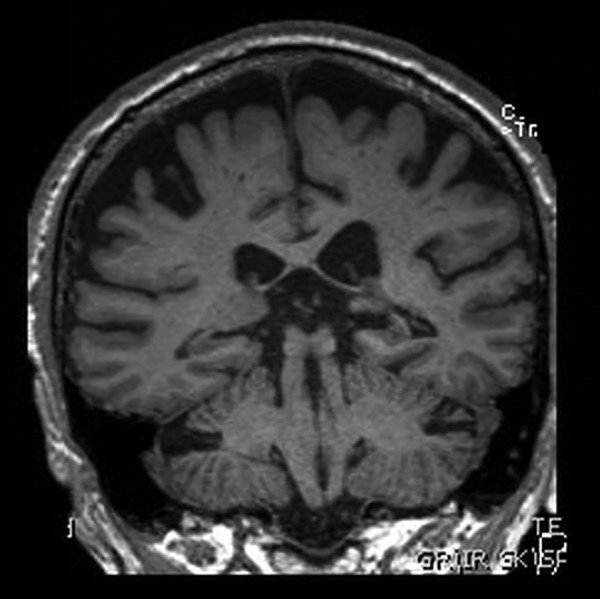

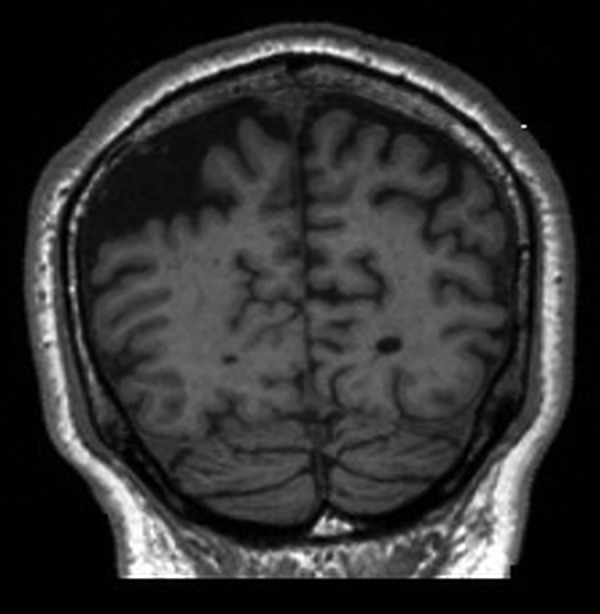

MRI of his brain (figures 1–3) demonstrated widened subdural spaces over both cerebral convexities, greater on the right side, with volume loss focused on the right parietal and occipital cortices. Hippocampal volume was reduced bilaterally. There was minimal signal abnormality in the basal ganglia and deep cerebral white matter of both hemispheres suggestive of small vessel disease. An EEG was also performed which was normal.

Figure 1.

Coronal sections of MRI of the brain: T1-weighted images.

Figure 2.

Coronal sections of MRI of the brain: T1-weighted images.

Figure 3.

Coronal sections of MRI of the brain: T1-weighted images.

Neuropsychological testing revealed a verbal IQ of 92—in the average range—on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III) and a low-average performance IQ of 80. These demonstrated a moderate decline relative to estimates of his optimal level of functioning. Visual memory and naming skills were weak and there was evidence of executive dysfunction and cognitive slowing.

Outcome and follow-up

The clinical and imaging findings were supportive of a diagnosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. In order to delineate the underlying aetiology, a lumbar puncture was proposed but the patient refused to undergo this procedure. Given the family history of MND, genetic testing was undertaken with PCR and then Southern blotting to identify a pathogenic expansion of the C9ORF72 gene. This confirmed the presence of a hexanucleotide repeat expansion at C9ORF72, providing the underlying genetic diagnosis for this case of FTD presenting with psychotic symptoms in a forensic setting.

Discussion

This case is of a male in his 50s presenting with psychotic symptoms with a somatic focus and cognitive decline caused by FTD due to a hexanucleotide repeat expansion at C9ORF72 (C9+). The case demonstrates a rare but important cause of psychotic symptoms and we feel that this should be an important potential differential diagnosis in patients presenting with psychotic symptoms in later life, especially in those with a positive family history of young-onset dementia or MND and in those with cognitive decline.

The role of a hexanucleotide repeat expansion at C9ORF72 in families with FTD with or without MND was only recently identified5 6 and represented a significant development in research into neurodegenerative disorders.

One study found that C9+ accounted for 11.7% of familial FTD5 while other studies have quoted a frequency of 28.6% in those patients with FTD and a positive family history of early-onset dementia or MND.7

Patients with C9+ present most commonly with symptoms of behavioural variant FTD (bvFTD), around 48–50% in most case series,8 9 but can present with a clinical picture of FTD-MND in 19–36% of cases or primary progressive aphasia in up to 19% of cases.10

As in this case, the mean age of onset of FTD in patients with C9+ is reported to be between 55 and 59.2 years and the mean duration of disease from onset until death between 7.6 and 9.5 years.7 9 10 Survival is worse and the cognitive decline is more rapid in people with C9+ FTD than in those with non-carrier FTD.11

In our case, a detailed family history from a collateral source was instructive in clarifying the likely diagnosis and evidence suggests that a family history of young-onset dementia or MND is present in around two-thirds of patients with C9+; more than one relative is affected in 39% of cases.4

It is well established that psychotic symptoms are seen in all forms of dementia,12 but there is strengthening evidence that psychotic symptoms are more common in those patients with FTD-MND13 and C9+ FTD. One study suggested that 38% of patients with C9+ FTD experienced psychotic symptoms compared with 4% of those with non-carrier FTD.4 Furthermore, as in this case, these are frequently the presenting symptoms: a study comparing early neuropsychiatric symptoms in 15 patients with bvFTD caused by C9+ versus 48 patients with non-carrier bvFTD showed that delusions were an initial presenting symptom in 21.4% of the C9+ patients compared with none of the non-carrying patients.8

Other presenting neuropsychiatric symptoms frequently seen early in C9+ FTD are disinhibition (63%), apathy (49%), disorganisation (45%), episodic memory loss (44%) and anxiety and agitation (40%). Neuropsychological testing shows executive dysfunction (100%), verbal or visual episodic memory loss (87%) and apraxia (57%). Neurological examination reveals brisk deep tendon reflexes in 40% of early cases, progressing to clinical evidence of MND in the majority.9

Neuroimaging demonstrates atrophy in the medial, ventral and dorsal frontal, anterior insular and anterior temporal lobes. Greater parietal and bilateral thalamic atrophy was seen in C9+ bvFTD than in non-carriers,8 and the parietal atrophy, especially on the right side, is notable on MRI in our case. Group brain morphometry studies have implicated a culprit corticothalamocerebellar network in the pathogenesis of C9+ FTD9: the finding of abnormal body schema processing in patients with C9+ FTD14 may reflect disintegration of this brain network and provide a substrate for the (often somatically focused) neuropsychiatric symptoms in these patients. There is little evidence for the effects of C9+ on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) parameters; one study found that all patients had normal levels of CSF cells, protein, glucose, aβ and S100 and only one had an abnormal CSF τ level.9

Learning points.

Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9ORF72) hexanucleotide repeat expansion-related frontotemporal dementia is an unusual and recently discovered genetic syndrome, which is a rare but important differential diagnosis for psychotic symptoms.

Doctors working in mental health, forensic, geriatric medicine and neurology settings need to be vigilant for symptoms of cognitive impairment in unusual presentations of psychosis in older people.

This case demonstrates the value of thorough collateral history and a focus on family history when rare neuropsychiatric presentations are encountered.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in the clinical care and diagnostic process for the patient. AS and JL reviewed the literature for information about the condition. AS, JL, JW and GP contributed substantially to the conception and design, and to the drafting of the article and its critical revision for intellectual content.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Vilalta-Franch J, Lopez-Pousa S, Calvo-Perxas L, et al. Psychosis of Alzheimers disease: prevalence, incidence, persistence, risk factors, mortality. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013;11:1135–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ropacki SA, Jeste DV. Epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer's disease: a review of 55 studies published from 1990 to 2003. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:2022–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omar R, Sampson EL, Loy CT, et al. Delusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Neurol 2009;256:600–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snowden JS, Rollinson S, Thompson JC, et al. Distinct clinical and pathological characteristics of frontotemporal dementia associated with C9ORF72 mutations. Brain 2012;135:693–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dejesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 2011;72:245–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 2011;72:257–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobson-Stone C, Hallupp M, Bartley L, et al. C9ORF72 repeat expansion in clinical and neuropathologic frontotemporal dementia cohorts. Neurology 2012;79:995–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sha S, Takada L, Rankin K, et al. Frontotemporal dementia due to C9ORF72 mutations: clinical and imaging features. Neurology 2012;79:1002–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahoney C, Beck J, Rohrer J, et al. Frontotemporal dementia with the C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion: clinical, neuroanatomical and neuropathological features. Brain 2012;135:736–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simón-Sánchez J, Dopper E, Cohn-Hokke P, et al. The clinical and pathological phenotype of C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions. Brain 2012;135:723–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irwin D, McMillan C, Brettschneider J, et al. Cognitive decline and reduced survival in C9orf72 expansion frontotemporal degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013;84:163–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy ML, Miller BL, Cummings JL, et al. Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementias: behavioral distinctions. Arch Neurol 1996;53:687–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lillo P, Garcin B, Hornberger M, et al. Neurobehavioural features in frontotemporal dementia with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2010;67:826–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downey LE, Mahoney CJ, Rossor MN, et al. Impaired self-other differentiation in frontotemporal dementia due to the C9ORF72 expansion. Alzheimers Res Ther 2012;4:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]