Abstract

Suspected paediatric aerodigestive tract foreign body (FB) ingestion or aspiration is a commonly encountered emergency. Management may require a general anaesthetic for retrieval with bronchoscopy, laryngoscopy and oesophagoscopy, each dependent on the history and investigations of the case in question. We describe the case of a foreign body, which was missed in the nasopharynx for more than 3 years and also discuss how pressures on National Health Service (NHS) referral and follow-up patterns may have altered the time course of the eventual discovery.

Background

Paediatric aerodigestive tract foreign bodies are a commonly encountered emergency, however, presentation in the nasopharynx is an important site to check and not to miss. We report the case of a foreign body (FB) in the nasopharynx, which was missed for over 3 years.

Nasopharyngeal foreign bodies are also not always considered in cases of an ingested or aspirated FB. Atypical symptoms correlated with the clinical history should prompt physicians to undertake further investigations at the earliest point.

This report highlights the difficulties in establishing a clinical diagnosis of a retained FB in the nasopharynx especially after perceived clearance following examination under anaesthetic. It also emphasises the problems that can be encountered with referral pathways in the National Health Service (NHS) preventing reassessment in hospital care being initiated.

Case presentation

A 4-year-old boy presented to the ear, nose and throat (ENT) outpatients clinic with a history of long-standing nasal blockage, rhinorrhoea and halitosis. Treatment had been initiated by his general practitioner (GP) and the ENT team in the form of several courses of antibiotics and nasal sprays. There was unfortunately no improvement in his symptoms. The history included associated loud snoring and witnessed apnoeic episodes. Clinical examination revealed congested rhinitic mucosa, reduced airflow bilaterally on nasal misting test and small tonsils. Flexible nasendoscopy could not be performed as it was not tolerated by the child in the outpatient environment. The patient was subsequently listed for adenotonsillectomy in view of his long-standing symptoms.

Investigations

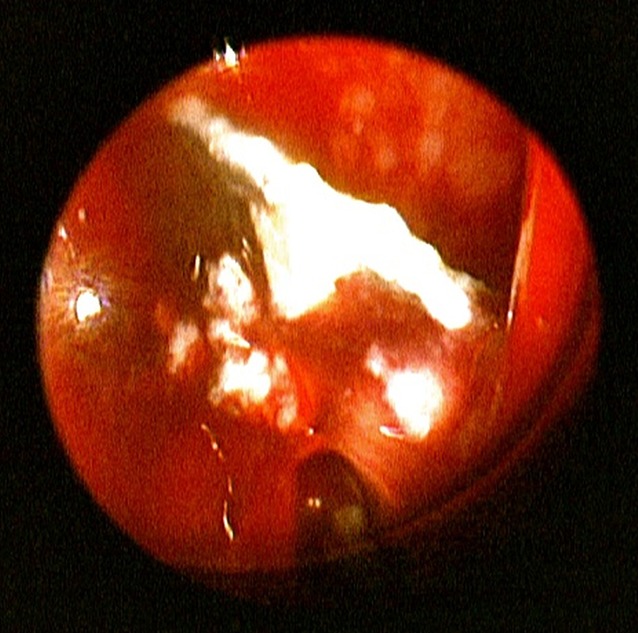

Under general anaesthetic, as part of the procedure to examine and remove the adenoids, obstruction was noted on passing a catheter to retract the soft palate. Rigid nasal endoscopic examination revealed a FB lodged firmly in the right postnasal space and occupying the right choana (figure 1). This was delivered with difficulty via the oropharynx using a curved negus (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Rigid nasal endoscopic view of nasal foreign body.

Figure 2.

Foreign body after removal.

Following the procedure, further details of the history were obtained from the child's mother. Three years previously, at age 9 months, the child was witnessed ingesting the same foreign body. The child had been assessed in the emergency department (ED) and transferred to the regional paediatric surgery department. An X-ray revealed no evidence of foreign body but the decision was made to perform an examination under general anaesthetic as an emergency. Documentation of the procedure recorded rigid and flexible endoscopy was used but no foreign body was seen in the oesophagus or the stomach. The child was discharged without follow-up and the mother told the FB would likely pass spontaneously.

A few months later the child started to develop the symptoms earlier described. His mother recounted that he had been suffering with poor appetite, was often unwell and once starting school was teased for having foul smelling breath. This led to social services being involved to investigate whether correct oral hygiene was being administered at home. During several GP consultations, it was explained that definitive investigations had already been performed and the possibility of a hereditary allergy from the child's father, who was of middle-eastern ethnicity, was also suggested. Re-referral for assessment in secondary care did not take place until the child's mother sought help from her local medical practitioner who then contacted the local ENT unit. Even after initial assessment in the ENT outpatient clinic there was a 2-year delay until operative intervention due to four cancellations. This was due to a combination of perceived upper respiratory tract infections and missed/cancelled appointments.

Differential diagnosis

Enlarged adenoids and tonsils, hereditary allergen.

Treatment

Examination under anaesthetic revealed a foreign body in the postnasal space occupying the right choana, which was subsequently removed (figures 1 and 2).

Outcome and follow-up

The patient has been followed up in our ENT outpatients department with no problems postoperatively. His weight has increased following improved appetite and he is progressing well at school. The family have noticed increased confidence and interaction with others, giving much relief.

Discussion

Foreign bodies in the nasopharynx are not always considered in cases of an ingested or possible aspirated FB. Lodging in the nasopharynx can occur through regurgitation following vomiting or forceful coughing. There have been cases reported, that digital manipulation in an attempt to remove the object can lead to lodging in the nasopharynx.1 It was not clear whether there was a history to suggest this in our case but it emphasises the requirement for clarifying this on history taking especially, in the paediatric population. When the decision is made to undertake examination under anaesthetic, the recommended management is that if no foreign body can be found on bronchoscopy, oesophagoscopy or laryngoscopy then examination of the nasopharynx should take place.2

It is often the case that children cannot tolerate flexible nasendoscopy however, in adults this would be performed in the ED or outpatient setting under local anaesthetic as part of the workup for possible ingested or aspirated FB. Recent studies have shown that there is no statistical difference in discomfort for children undergoing flexible nasendoscopy after a placebo, topical anaesthetic or nasal decongestants.3 It should therefore be attempted however, if not tolerable the examination of the postnasal space should take place at the time of general anaesthesia.

Thirty per cent of cases with ingestion of a FB are unwitnessed and usually children are afraid to confess to having placed such an object in their mouth or nose.4 In our case parents had witnessed this and were convinced that it had never passed. The mother’s index of suspicion and persistence played a key role in the re-referral of her son to secondary care for further investigations. Symptoms such as mucopurolent unilateral nasal discharge would ordinarily infer to clinicians the presence of a nasal foreign body. However, as there was documented evidence that no foreign body was seen on examination under anaesthetic it was placed further down the differential diagnosis list and initially not considered at all. Atypical symptoms such as halitosis, intermittent epistaxis, snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea,3 all which our patient had, should perhaps push clinicians to investigate more promptly in the context of a previous foreign body inhalation. Investigations should also be expedited even in the case of cancellations.

The current climate of the modern NHS with GPs paying for referrals can make it difficult to justify re-referrals to secondary care once the patient has already been seen and a clear plan documented. One would argue that there should be more support from hospital clinicians if symptoms do not resolve following surgical interventions.

Learning points.

Reinforce the importance of examining the postnasal space in ingested or aspirated foreign bodies particularly when not identified at time of theatre. This is particularly pertinent in the paediatric population as flexible nasendoscopy under local anaesthetic is not always amenable both at the time of ingestion or in the outpatient setting.

It serves as a reminder to ensure histories are revisited especially when symptoms are not resolving and thus prompt further investigation.

There are a number of pressures that face primary care clinicians but clarification of management plans from the specialist teams should always be sought. This will also allow the discharging team to ensure all possible outcomes have been considered.

Footnotes

Contributors: JGM performed the literature search and the case note review was performed by TT.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bhandary SK, Kolathingal B, Bhat VS, et al. Common foreign body, unusual site. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011;145:1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macneii SD, Moxham JP, Kozak FK. Paediatric aerodigestive foreign bodies: remember the nasopharynx. J Laryngol Otol 2010;124:1132–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chadha NK, Lam GO, Ludemann JP. Intranasal topical local anaesthetic and decongestant for flexible nasendoscopy in children: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;139:1301–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pirotte T, Ikabu C. Nasal foreign bodies in children: a possible pitfall for the anesthesiologist. Pediatr Anesth 2005;15:1108–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]