Abstract

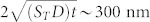

Single transient laser-induced microbubbles have been used in microfluidic chips for fast actuation of the liquid (pumping and mixing), to interact with biological materials (selective cell destruction, membrane permeabilization and rheology) and more recenty for medical diagnosis. However, the expected heating following the collapse of a microbubble (maximum radius ~ 10–35 µm) has not been measured due to insufficient temporal resolution. Here, we extend the limits of non-invasive fluorescence thermometry using high speed video recording at up to 90,000 frames per second to measure the evolution of the spatial temperature profile imaged with a fluorescence microscope. We found that the temperature rises are moderate (< 12.8°C), localized (< 15 µm) and short lived (< 1.3 ms). However, there are significant differences between experiments done in a microfluidic gap and a container unbounded at the top, which are explained by jetting and bubble migration. The results allow to safe-guard some of the current applications involving laser pulses and photothermal bubbles interacting with biological material in different liquid environments.

Short lived vapor microbubbles can be created by the absorption of laser pulses in liquid environments. The rapidly expanding bubbles later collapse driven by the pressure of the surrounding liquid. The oscillation of the bubbles induce fast flow, intense shear, shock wave emissions and adiabatic heating. These physical mechanisms are utilized in many experiments with microfluidic chips and biological material, examples are: pumping1, mixing (fast vortices)2,3, dropplet coalescence4, single cell destruction5,6, cell membrane poration7,8 and microrheology9. Several of these applications rely on nanosecond laser pulses absorbed with the help of dyes10, nanoparticles11,12,13,14,15, microparticles8,16 and nonlinear absorption5,9,17. Other biomedical laser applications include eye surgery18, tattoo removal19 and laser microdissection20. Recently, photothermal nanobubbles were used for needle-free malaria detection21.

Despite the success of laser-induced bubbles in combination with microfluidic chips and biomedical applications, there remains an open question about the amount and spatial distribution of heat generated by these microscopic bubbles inside confined liquid geometries. Experiments with macroscopic bubbles (radius ~ 10 mm) created by the arrest tube method inside a 1 m long tube have shown temperature increases of up to 4°C during the collapse of the bubble22. Experiments with microscopic laser-induced bubbles in combination with biological material hint at moderate temperature rises, since it has been possible to reversibly permeabilize and stretch biological cells while retaining viability7,9. Inside microfluidic channels, non-spherical bubble collapse may lead to liquid jetting3 which could result in enhanced cooling through thermal advection from the vorticity generated.

To our knowledge there have been no measurements of the temperature distribution following the collapse of a laser-induced cavitation microbubble. Here we use fluorescence based thermometry23,24,25,26 combined with high speed recording to spatially and temporally resolve the temperature distribution after the oscillation of a single laser-induced microbubble inside a microfluidic liquid gap. The maximum radius (~10–35 µm) of these bubbles is similar to bubbles used in some microfluidic experiments in combination with biological material7,8 and bubbles created with other photothermal methods14,27. In order to understand what are the effects of the geometry on heat deposition and dissipation, experiments are also done in an unbounded liquid (at the top) geometry to compare the results with those inside the microfluidic gap.

Results

Experimental setup

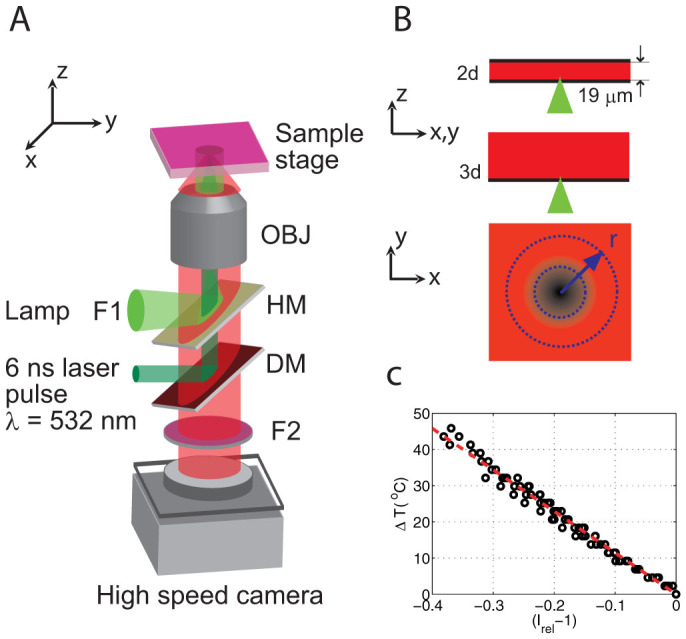

The experimental setup is depicted in Fig. 1A. Single laser pulses (duration of 6 ns and wavelength of 532 nm) from a frequency doubled Nd:YAG laser (New Wave, Orion) are used to create the bubbles by focusing the pulses inside the containers (microfluidic gap and unbounded) filled with fluorophore solution. The beam is expanded and then coupled into an inverted microscope (Olympus IX-71) through a dichroic mirror (DM) that reflects light at 532 nm. Then the light is transmitted through a 50/50 half mirror (HM) and is focused at the bottom of the fluorophore container using a 40× (0.8 NA) water immersion microscope objective (OBJ).

Figure 1.

(A) Experimental setup. DM, dichroic mirror. HM, 50/50 half mirror. OBJ, microscope objective. F1 and F2, filters. (B) Geometry of the liquid containers, microfluidic gap and semi-infinite liquid. Also shows the plane where the temperature is measured and averaged over concentric circles with radius r centered where the laser is focused and where the temperature is the highest after the bubble collapse. (C) Temperature calibration: temperature increase ΔT as a function of (Irel − 1).

The experiments are done using two different containers for the fluorophore solution (Fig. 1B): a thin microfluidic gap bounded at the top and at the bottom with #1 coverglass (0.13–0.16 mm thick) separated by spacers with a height of 19 ± 2 µm; and a small petri dish with a #1 coverslip glass bottom filled up to a height of 3 mm (resembling a semi-infinite liquid), i.e. much larger than the size of the bubble.

For the temperature measurements we use single-color intensiometric thermometry, since it only requires a simple epifluorescence light path that can be combined with the optical elements that couple the laser pulses to the microscope objective (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the choice of single color fluorescence is justified under the assumption of a constant fluorophore concentration, which we will discuss later (Discussion). The fluorophore solution is excited by a Mercury fluorescent lamp (F1: excitation filter for 480–550 nm) reflected by the HM into the microscope objective. The fluorescence is recorded by a high speed camera (SA1.1, Photron) at up to 90,000 fps for the semi-infinite liquid and 54,000 fps for the thin liquid gap. The fluorescence emission filter (F2: long pass 590 nm) is placed in front of the camera.

Temperature calibration

In order to find the relation between fluorescence intensity I and temperature, a small glass container with a calibrated thermistor is filled with fluorophore solution (see Methods) to a height ~3 mm and sealed at the top with a Peltier heating element. The container is placed on the same experimental setup and is slowly heated while the fluorescence intensity is recorded (100 frames for selected temperatures) with the high speed camera at a frame rate of 54,000 fps during several heating and cooling cycles (from room temperature at 21.6 to 65°C). The intensity for each frame is integrated and averaged over the set of frames. Photobleaching is not observed for times greatly exceeding the duration of the experiments (<7 ms). Additional data is shown in the Methods section. We find a linear relation between temperature and intensity: T(I) = a + bI in the explored temperature range. Hence, the temperature increase ΔT = T − 21.6°C can be expressed as ΔT = T0(Irel − 1), where T0 is a constant and Irel = I/I(21.6°C). Figure 1C shows the results for six calibration experiments where the temperature increase ΔT is plotted as a function of Irel − 1. The linear fit to the data yields T0 = −114.5 ± 1.6°C where the error represents the confidence bounds within 95%.

Experiment

Single laser pulses are focused at the bottom of the containers (for both geometries), above the bottom coverslip (2 µm). The molecules in the focal volume could be bleached by the focused laser light. An estimate for that volume can be obtained by considering the size of the ellipsoid at the focal volume using the diffraction limited spot size w0 = 0.41 µm and a Rayleigh length of zR = 2.16 µm. This is equivalent to a volume of 0.7 femtoliters, which is negligible compared with the volume of the liquid contained in the vicinity of the irradiated spot. These molecules should be mixed with the rest of the solution during the bubble dynamics. Hence if the molecules in the focal volume are bleached, we can neglect them. We also assume that the fluorophore concentration does not change after the cavitation event and the possible effects of the bubble dynamics and thermophoresis are negligible (Discussion). The energies used for the laser pulse are in the range of 1–9 µJ, resulting in bubbles with a maximum transverse radius (xy plane) between 10–35 µm for both geometries. For each geometry the experiment is repeated five times at each laser energy and the temperature distributions T(r, t) are extracted for each experiment separately.

Image analysis

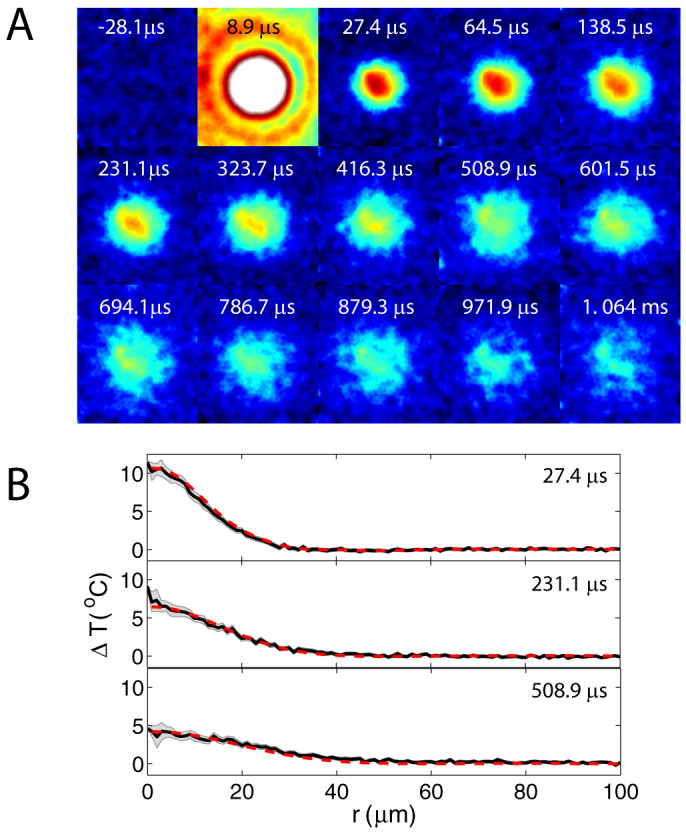

To analyze the dynamics of the temperature distribution, we averaged several hundred images (300 for the thin gap and 600 for the semi-infinite liquid) prior to the laser irradiation which gives us the fluorescence intensity at room temperature. Then each of the next 300–600 frames recorded during and after the arrival of the laser pulse is divided by the averaged room temperature image (to obtain Irel). In this way we are left with 300–600 images of the relative fluorescence intensity (minus one or two saturated images that show the arrival of the laser pulse and the bubble dynamics). Figure 2A shows representative Irel images (converted to ΔT) recorded at 54,000 fps before and after the arrival of a single laser pulse (8.6 µJ) in the microfluidic liquid gap. The images were filtered with a circular averaging filter with a radius of four pixels in order to increase the signal-to-noise ratio (Video file provided in Supplementary Video 1). The Irel(x, y, t) images are analyzed without filtering and the relative fluorescence intensity is averaged over concentric circles (radius r on xy plane) around the irradiated spot in a range L = 100 µm (Fig. 1B). The number of points in the perimeter increases linearly with the radius, as a result, the standard error of the mean ( , σ is the standard deviation and n the number of points) decreases with increasing r. Then, Irel(r, t) is converted to ΔT(r, t) using the calibration. An example of ΔT(r, t) extracted from unfiltered intensity ratios for some of the cases in Fig. 2A are shown in Fig. 2B. Reliable measurements of the temperature distributions are made at ~35 µs after the arrival of the laser pulse, that is, the first measurement is taken at 25 to 33 µs after the collapse of the bubble.

, σ is the standard deviation and n the number of points) decreases with increasing r. Then, Irel(r, t) is converted to ΔT(r, t) using the calibration. An example of ΔT(r, t) extracted from unfiltered intensity ratios for some of the cases in Fig. 2A are shown in Fig. 2B. Reliable measurements of the temperature distributions are made at ~35 µs after the arrival of the laser pulse, that is, the first measurement is taken at 25 to 33 µs after the collapse of the bubble.

Figure 2.

(A) Temperature distribution filtered with a circular average to reduce noise (thin gap, Elaser = 8.6 µJ). Video file provided in Supplementary Video 1. Size of each image is 101 × 116 µm (W × H). (B) Temperature distribution averaged at every r with no filtering. The dotted line represents a fit to a simple heat diffusion model.

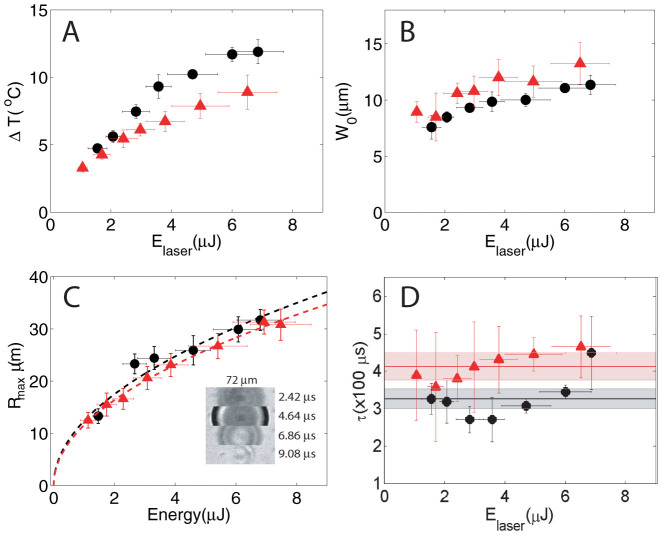

Figure 3 compares the maximum temperature rise, distribution, bubbles dynamics, and cooling rates for the two geometries (black circles: microfluidic gap, red triangles: semi-infinite liquid). First, the maximum temperature rise above the initial temperature distribution ΔT0(r = 0, t0) is plotted in Fig. 3A as a function of the laser energy. The maximum temperature is higher for the microfluidic gap for similar laser energies. The largest measured temperature rise is 11.9 ± 0.9°C and 8.9 ± 1.3°C for the microfluidic gap and semi-infinite liquid respectively. If we consider that a similar amount of heat is deposited in both geometries, less liquid in the vicinity of the irradiated area for the microfluidic gap could explain the higher temperatures. The measured radial width (half width at half maximum) of the initial temperature distribution as a function of the laser pulse energy is plotted in Fig. 3B. The initial widths are similar for both containers. Figure 3C shows the lateral (xy plane) maximum bubble radius which was captured in another set of experiments with similar energy range of the laser pulses but recorded at 450,000 fps and imaged in bright field. A bubble created inside the microfluidic gap is shown in Fig. 3C (inset). The maximum radius squared has a linear relation to the laser energy  and it is very similar for both geometries. The constant a for the thin gap a2d = 152.8 ± 18.4 µm2/µJ, is slightly larger than for the semi-infinite liquid configuration a3d = 133.7 ± 5.8 µm2/µJ.

and it is very similar for both geometries. The constant a for the thin gap a2d = 152.8 ± 18.4 µm2/µJ, is slightly larger than for the semi-infinite liquid configuration a3d = 133.7 ± 5.8 µm2/µJ.

Figure 3.

(A) Maximum temperature rise ΔT as a function of the laser pulse energy (Elaser) for both chamber geometries. (B) Half width at half maximum of the initial temperature distribution after the bubble collapse (W0). (C) Maximum bubble radius Rmax as a function of laser energy obtained from experiments in bright field at 450,000 fps. The dashed lines,  , where a is the constant. Inset: sample of high speed video frames of a single cavitation event (microfluidic gap). (D) Time it takes the maximum temperature to drop by 1/e (τ) as a function of Elaser. Thin liquid gap: black circles, semi-infinite liquid: red triangles.

, where a is the constant. Inset: sample of high speed video frames of a single cavitation event (microfluidic gap). (D) Time it takes the maximum temperature to drop by 1/e (τ) as a function of Elaser. Thin liquid gap: black circles, semi-infinite liquid: red triangles.

Discussion

In the semi-infinite liquid container the bubble has a hemispherical shape, hence we can use the 3d Rayleigh-Plesset equation to calculate the oscillation time  , where ρ is the liquid density, p∞ is the hydrostatic pressure (105 Pa), and pv is the vapor pressure (2330 Pa for water). For the largest hemispherical bubbles the oscillation time τosc is under 7 µs, consistent with the bright field high speed recordings. The bubbles created in the microfluidic gap are not planar, since Rmax is on the order of the height H of the gap. For these bubbles τosc increases as the ratio η = H/Rmax decreases28. High speed recordings in bright field showed that τosc < 10 µs. In the limit η → 0, the shrinkage of the bubble is planar and can be fitted to a 2d Rayleigh-Plesset equation. There are different collapse scenarios that depend on η29. For η in the range of (0, 0.4) there is planar collapse between both boundaries, upward jetting towards the upper boundary is expected for (0, 1), while for η within (1, 1.4) the bubble collapses neutrally. Finally, for η > 1.4 jetting is directed toward the bottom boundary. In the microfluidic gap Rmax are between 15–32 µm, hence η has a range between 0.5 and 1.5, which should result mainly in upward jetting for the highest Rmax or Elaser and neutral collapse and probably downward jetting for the smallest bubbles.

, where ρ is the liquid density, p∞ is the hydrostatic pressure (105 Pa), and pv is the vapor pressure (2330 Pa for water). For the largest hemispherical bubbles the oscillation time τosc is under 7 µs, consistent with the bright field high speed recordings. The bubbles created in the microfluidic gap are not planar, since Rmax is on the order of the height H of the gap. For these bubbles τosc increases as the ratio η = H/Rmax decreases28. High speed recordings in bright field showed that τosc < 10 µs. In the limit η → 0, the shrinkage of the bubble is planar and can be fitted to a 2d Rayleigh-Plesset equation. There are different collapse scenarios that depend on η29. For η in the range of (0, 0.4) there is planar collapse between both boundaries, upward jetting towards the upper boundary is expected for (0, 1), while for η within (1, 1.4) the bubble collapses neutrally. Finally, for η > 1.4 jetting is directed toward the bottom boundary. In the microfluidic gap Rmax are between 15–32 µm, hence η has a range between 0.5 and 1.5, which should result mainly in upward jetting for the highest Rmax or Elaser and neutral collapse and probably downward jetting for the smallest bubbles.

The data analysis on the dynamics of the temperature distributions are done under the assumption that the fluorophore concentration does not significantly change after the cavitation event, that after the collapse of the bubble there are no appreciable gradients in the fluorophore concentration set by the bubble dynamics or by thermophoresis. First, we consider the diffusion coefficient of the fluorophore molecules (10 kDa TMR dextran at 10 mg/ml) in water. The diffusion coefficient as a function of molecular weight for FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate) dextran solutions between 4 and 2000 kDa can be calculated using D = α (molecular weight)β (cm2/s), α = 2.71 × 10−5 for dilute solutions (0.1 mg/ml) at 25°C30. The calculated diffusion coefficient for our 10 kDa sample is 8.97 × 10−7 cm2/s ~ 90 µm2/s. The effect of the high concentration (10 mg/ml) in our TMR solution is to decrease the diffusion coefficient by about 7%31. However, we can use the higher value of D = 90 µm2/s as an upper bound, which is much smaller than the thermal diffusivity of water (1.5 × 105 µm2/s). Next, we consider the effects of the bubble dynamics. During expansion it is possible that there could be an increase in fluorophore concentration around the edges of the bubble. However, in the collapse there is jetting and vorticity that should quickly mix the solution. The longest lifetime of the bubbles is τosc ~ 10 µs and our earliest measurements are done at 25 to 33 µs after the collapse of the bubble. The fluorophore concentration after the bubble collapses should be very similar to that before the bubble generation. Another possible source for a concentration gradient is the thermal gradient during absorption of the laser energy and in the bubble collapse, which could cause a redistribution of the fluorophore by thermophoresis. This effect is estimated using reported Soret coefficients (ST) for aqueous solutions of dextran with similar concentrations (1, 5 and 10 mg/ml) and higher molecular weight (FITC dextran 86.7 kDa, D ~ 2.8 × 10−7 cm2/s = 28 µm2/s)32 which underestimates the diffusivity in our sample by a factor of three. The reported ST32 at the temperature range of interest for this experiment (21–35°C, after the bubble collapse) lies between −0.05 and −0.025. At higher temperatures (~ 45°C) ST vanishes and becomes positive (migration toward colder regions) and at 55°C, ST ~ 0.025. In our experiment, the timescales for energy deposition and heating are very short: 6 ns during absorption and a submicrosecond bubble collapse. The initial heating during absorption of the laser pulse (6 ns) is followed by cooling during expansion of the bubble and finally heating with the collapse of the bubble. The highest temperatures should be achived during absorption of the laser pulse. However the very brief timescales of the processes allow us to neglect thermophoresis even if ST increased by several orders of magnitude due to high temperatures in our sample. The fluorophore diffusion length in 10 µs (upper bound) and considering ST = 250 (4 orders of magnitude the value at 55°C) is  . Similar results are obtained if we assume that the initial thermal gradient (T ~ (21, 35)°C and ST ~ (−0.05, −0.025)) set after the bubble collapse is constant (continuous heating) for the duration of the experiment < 7 ms. Hence we can assume that the fluorophore concentration is constant which justifies the use of single color intensiometric thermometry and allows us to analyze our data under the assumption of a constant thermal diffusion coefficient or thermal diffusivity.

. Similar results are obtained if we assume that the initial thermal gradient (T ~ (21, 35)°C and ST ~ (−0.05, −0.025)) set after the bubble collapse is constant (continuous heating) for the duration of the experiment < 7 ms. Hence we can assume that the fluorophore concentration is constant which justifies the use of single color intensiometric thermometry and allows us to analyze our data under the assumption of a constant thermal diffusion coefficient or thermal diffusivity.

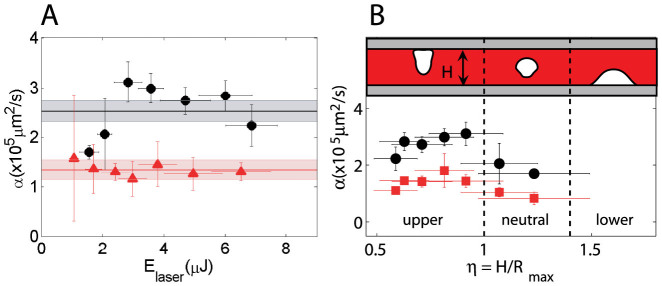

Next, we look at the heat diffusion and re-thermalization of the liquid. The initial temperature distribution (ΔT(r, t) measured just above the bottom boundary) should decay exponentially in time according to the heat diffusion equation α∇2T = ∂tT, where α is the thermal diffusivity. To simplify the notation we refer to the measured ΔT(r, t) as T(r, t), which can be expressed as a product of a spatial and a temporal part T(r, t) = F(r)G(t). The temporal solution is a decaying exponential exp(−λt), where λ is proportional to the diffusivity α. To get an idea of the decay rate λ we measure the time that it takes for the initial maximum temperature Tmax(r = 0, t0) to drop to a value of Tmax/e, we label this time by τ. τ is plotted on Fig. 3D as a function of the laser pulse energy. The mean value of all the data points for the thin liquid gap is τ2d = 326 ± 26 µs (central black line bounded by standard error of the mean) and for the semi-infinite liquid is τ3d = 412 ± 36 µs (red line). Interestingly we observe that for the semi-infinite liquid all the data points are close to the shaded area within the error bars, suggesting that τ3d (or λ3d) is constant or has little change for different Elaser/Rmax. In the case of the microfluidic gap the variation of τ2d hints at different dissipation rates that depend on Elaser/Rmax which can be related to different collapse scenarios (η) that can include jetting. The time for the temperature rise to drop to a 0.5% is about 3τ which gives a time of 1.3 and 1 millisecond for the semi-infinite liquid and microfluidic gap respectively, consistent with our measurements.

To examine the effect of the boundaries we calculate the thermal diffusion length during the short times of the process (~ 1 millisecond). The diffusivities for water and glass are 1.5 × 105 and 3.4 × 105 µm2/s respectively. For water the thermal diffusion length over a time of 1 ms is 24.4 µm, while for glass it is 36.8 µm, which are smaller than the thickness of the cover glass.

Model

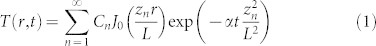

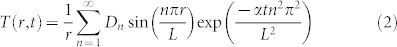

The evolution of the measured temperature profiles are fitted to the analytic solution of the heat diffusion equation (neglecting the boundaries) in order to extract effective thermal diffusivities. For the thin gap we treat the heat diffusion as a 2 dimensional (2d) problem because the transverse range (L = 100 µm) in T(r, t) is larger than the height of the gap H. The case of the semi-infinite liquid is treated as an isotropic 3d temperature distribution (even though we only have half a sphere) problem in spherical coordinates. For both problems the boundary condition is T(r = L, t) = 0. The transverse range L is chosen because for the range of laser energies used, we do not detect temperature increases at that distance. Even if the fitted values of the extracted effective diffusivities changed by choosing a different L, we are interested in the relative differences between the extracted values for both containers. The Fourier series solution for the heat equation (with no sources) in 2d33 and 3d34 are:

|

|

where  , zn are the zeros of the Bessel function and

, zn are the zeros of the Bessel function and  .

.

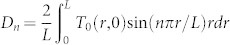

The amplitudes are fitted to the initial temperature profile T(r, t0) and the diffusivity is fitted to a temperature profile at a later time (Dotted lines in Fig. 2B). The predicted evolution of the temperature profiles are in good agreement with the measurements. The fitted effective diffusivities α for each experiment (single bubble) are shown in Fig. 4A. Considering all the data the effective thermal diffusivities are α = (2.51 ± 0.21) × 105 µm2/s and (1.34 ± 0.20) × 105 µm2/s for the thin liquid gap and the semi-infinite liquid respectively (black and red lines in Fig. 4A). In the semi-infinite liquid configuration we recover an effective thermal diffusivity very close to the value of water and all the data is centered around the mean value for all the pulse energies, similar to τ3d in Fig. 3D. This suggests that the temperature distribution is isotropic (in half a sphere). In contrast, for the microfluidic gap the fitted values of α are scattered around the mean value and depend on the laser energy (similar to τ2d) hinting at a 3d temperature distribution with different dissipation rates that depend on Elaser/Rmax and hence the different collapse scenarios given by η. Furthermore, the effective average value of the thermal diffusivity is almost twice that of water (from the ratio τ2d/τ3d = α2d/α3d ~ 1.3 we expected an average value of α2d ~1.3 × α3d). The cylindrical distribution of the 2d model overestimates the average of the thermal diffusivity.

Figure 4.

(A) Thermal diffusivity (α) plotted as a function of Elaser. Thin gap: black circles, semi-infinite liquid: red triangles.(B) Microfluidic gap: α as a funtion of η, α extracted from fits to 2d model (circles) and 3d model (squares). Drawing: expected collapse and jetting conditions for different ranges of η.

Figure 4B shows the thermal diffusivity data for the microfluidic gap as a function of η, where the black circles and red squares are the extracted αs from the 2d and 3d model respectively. The average value of the 3d fits is α = 1.27 ± 0.15 × 105 µm2/s, which underestimates the expected average value of α2d (1.3 × α3d). Both data sets show essentially the same trend suggesting variable dissipation rates that depend on η, with the faster dissipations for the cases with upward jetting (0.5 < η < 1), and the slowest for the conditions of neutral collapse and downward jetting which is closer to the case of the collapse on the semi-infinite liquid geometry (η → ∞). Interestingly, we observe in both data sets that the value of α decreases for η approaching 0.5, which hints at a lower heat dissipation rate for the case of a slower planar collapse (0 ≤ η ≤ 0.4). Finally, we can estimate the amount of heat deposited after the collapse of a bubble by integrating the initial temperature distribution (assume isotropic on half sphere) multiplied by the specific heat, which yields between 5 and 10% of the laser pulse energy.

In summary, we have shown that for the range of laser pulse energies and maximum bubble sizes, the temperature rise resulting from the oscillation of a single bubble is moderate, short lived and localized. Interestingly, the temperature distribution is a function of the geometry bounding the flow, which we explain with different jetting conditions (heat dissipation rates) during the collapse of the bubble. These results allow to safe-guard some of the current applications involving focused laser pulses and photothermal bubbles.

Methods

Fluorophore solution

Water soluble tetramethylrhodamine attached to 10,000 MW dextran (TMR-Dextran) acts as the molecular thermometer. The fluorophore solution was prepared by dissolving the TMR-Dextran powder (Invitrogen, D1816) in distilled water (10 mg/ml). Even at the fastest recording times of 90,000 fps, the exposure time is much longer than the relaxation time of TMR which is on the order of nanoseconds.

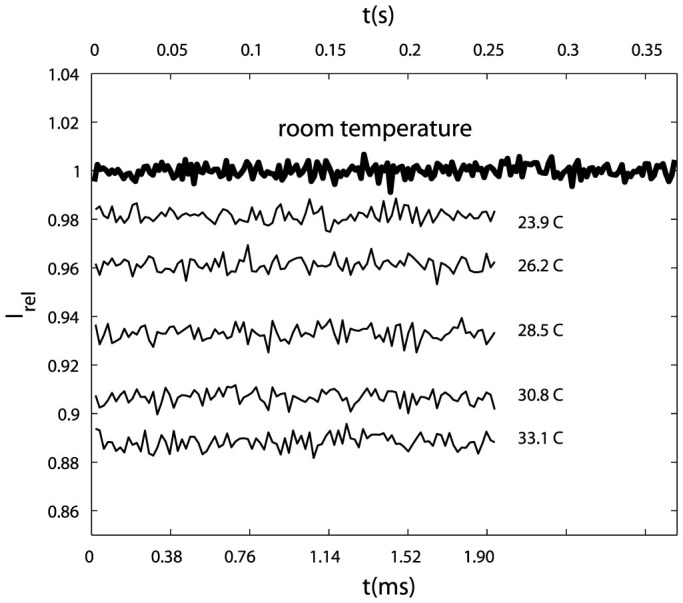

Figure 5 shows the relative fluorescent intensity recorded at 54,000 fps for more than 0.35 s (bold line, upper timescale), which greatly exceeds the duration of each experimental run. Hence we can discard photobleaching due to the excitation lamp. Also in Fig. 5 we show some of the data for the calibration (100 frames, lower timescale).

Figure 5. Relative fluorescent intensity at room temperature recorded at 54,000 fps.

Room temperature data (bold line) recorded for about 0.37 s (upper time scale), each point corresponds to the average of one frame, adjacent points separated by 100 frames. Thin lines are samples of the calibration data with a duration of 1.9 ms (lower time scale).

Supplementary Video 1. Video for the case shown in Figure 2 (evolution of the temperature distribution), 102 × 102 µm (W × H) filtered with a circular averaging filter with a radius of four pixels. The total duration is 6.5 milliseconds.

Author Contributions

The idea was conceived by M.S. and C.D.O. P.A.Q.S. and M.S. carried out the experiments at NTU. P.A.Q.S. assembled the experimental setup, analyzed and interpreted the data. All the authors contributed writing the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Video 1

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the following grants: Nanyang Technological University Grant No. RG39/07 and The Ministry of Education, Singapore Grant No. T208A1238. Grant-in-Aid for a Young Scientist (A) (No. 23687021) and the Supporting Project to Form the Strategic Research Platforms for a Private University from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. CONACYT grant No. 153821.

References

- Dijkink R. & Ohl C. D. Laser-induced cavitation based micropump. Lab Chip 8, 1676–1681 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman A. N. et al. Laser-induced mixing in microfluidic channels. Anal. Chem. 79, 4484–4492 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaan E., Le Gac S., Tsuji K. & Ohl C. D. Controlled cavitation in microfluidic systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 254501 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. G. et al. Fast on-demand droplet fusion using transient cavitation bubbles. Lab Chip 11, 1879 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinto-Su P. A. et al. Examination of laser microbeam cell lysis in a pdms microfluidic channel using time-resolved imaging. Lab Chip 8, 408–414 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai H.-H. et al. Characterization and use of laser-based lysis for cell analysis on-chip. J. R. Soc. Interface 5, S113–S121 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. G., Liu A. Q., Klaseboer E., Zhang J. B. & Ohl C. D. Single cell membrane poration by bubble-induced microjets in a microfluidic chip. Lab Chip 13, 1144–1150 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gac S., Zwaan E., van den Berg A. & Ohl C. D. Sonoporation of suspension cells with a single cavitation bubble in microfluidic confinement. Lab Chip 7, 1666–1672 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinto-Su P. A., Kuss C., Preiser P. R. & Ohl C. D. Red blood cell rheology using single controlled laser-induced cavitation bubbles. Lab Chip 11, 672–678 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark I. B. et al. Optoinjection for efficient targeted delivery of a broad range of compounds and macromolecules into diverse cell types. J. Biomed. Opt. 11, 014034 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z. et al. Evolution of light-induced vapor generation at a liquid-immersed metallic nanoparticle. Nano Lett. 13, 17361742 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotaidis V., Dahmen C., von Plessen G., Springer F. & Plech A. Excitation of nanoscale vapor bubbles at the surface of gold nanoparticles in water. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 184702 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukianova-Hleb E. et al. Plasmonic nanobubbles as transient vapor nanobubbles generated around plasmonic nanoparticles. ACS Nano 4, 21092123 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitsillides C. M., Joe E. K., Wei X., Anderson R. R. & Lin C. P. Selective cell targeting with light-absorbing microparticles and nanoparticles. Biophys. J. 84, 4023–4032 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlani E. P., Karampleas I. H. & Xie Q. Analysis of pulsed laser plasmon-assisted photothermal heating abd bubble generation at the nanoscale. Lab Chip 12, 3707–3719 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankin G. N., Yuan F. & Zhong P. Pulsating tandem microbubble for localized and directional single-cell membrane poration. Phys. Rev. Lett. (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau K. R., Quinto-Su P. A., Hellman A. N. & Venugopalan V. Pulsed laser microbeam-induced cell lysis: Time-resolved imaging and analysis of hydrodynamic effects. Biophys. J. 91, 317–329 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docchio F., Sacchi C. A. & Marshall J. Experimental investigation of optical breakdown thresholds in ocular media under single pulse irradiation with different pulse durations. Lasers Ophthalmol. 1, 83–93 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Kent K. M. & Graber E. M. Laser tattoo removal: a review. Dermatol. Surg. 38, 1–13 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berns M. W. et al. Laser microsurgery in cell and developmental biology. Science 213, 505–513 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukianova-Hleb E. Y. et al. Hemozoin-generated vapor nanobubbles for transdermal reagent-and needle-free detection of malaria. PNAS, Early Edition, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dular M. & Coutier-Delgosha O. Thermodynamic effects during growth and collapse of a single cavitation bubble. J. Fluid Mech. 736, 44–66 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Low P., Kim B., Takama N. & Bergaud C. High-spatial resolution surface-temperature mapping using fluorescent thermometry. Small 4, 908–914 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodner P. & Tyson J. A. Microscopic fluorescent imaging of surface temperature profiles with 0.01 c resolution. Appl. Phys. Lett. 40, 782 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Romano V., Zweig A. D. & Weber H. P. Time-resolved thermal microscopy with fluorescent films. Appl. Phys. B 49, 527–533 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Cordero M. L., Verneuil E., Gallaire F. & Baroud C. N. Time-resolved temperature rise in a thin liquid film due to laser absorption. Phys. Rev. E 79, 011201 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapotko D. O., Lukianova E. & Oraevsky A. A. Selective laser nano-thermolysis of human leukemia cells with microbubbles generated around clusters of gold nanoparticles. Laser. Surg. Med. 38, 631–642 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinto-Su P. A., Lim K. Y. & Ohl C. D. Cavitation bubble dynamics in microfluidic gaps of variable height. Phys. Rev. E 80, 047301 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Avila S. R., Klaseboer E., Khoo B. C. & Ohl C. D. Cavitation bubble dynamics in a liquid gap of variable height. J. Fluid Mech. 682, 241–260 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Gribbon P. & Hardingham T. E. Macromolecular diffusion of biological polymers measured by confocal fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Biophys. J. 75, 1032–1039 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent T. C., Sundelof L.-O., Wik K. O. & Warmegard B. Diffusion of dextran in concentrated solutions. Eur. J. Biochem. 68, 95–102 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugaya R., Wolf B. & Kita R. Thermal diffusion of dextran in aqueous solutions in the absence and the presence of urea. Biomacromolecules 7, 435–440 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchil R. V. & Brown J. W. Fourier series and boundary value problems (McGraw-Hill, 1941). [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth J. & Duarte F. J. Heat diffusion in a solid sphere and fourier theory: An elementary practical example. Am. J. Phys. 47, 981–983 (1979). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Video 1