Abstract

Background & objectives:

Randomized controlled trials in developed countries have reported benefits of Lactobacillus GG (LGG) in the treatment of acute watery diarrhoea, but there is paucity of such data from India. The study was aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Lactobacillus GG in the treatment of acute diarrhoea in children from a semi-urban city in north India.

Methods:

In this open labelled, randomized controlled trial 200 children with acute watery diarrhoea, aged between 6 months to 5 years visiting outpatient department and emergency room of a teaching hospital in north India were enrolled. The children were randomized into receiving either Lactobacillus GG in dose of 10 billion cfu/day for five days or no probiotic medication in addition to standard WHO management of diarrhoea. Primary outcomes were duration of diarrhoea and time to change in consistency of stools.

Results:

Median (inter quartile range) duration of diarrhoea was significantly shorter in children in LGG group [60 (54-72) h vs. 78 (72-90) h; P<0.001]. Also, there was faster improvement in stool consistency in children receiving Lactobacillus GG than control group [36 (30-36) h vs. 42 (36-48) h; P<0.001]. There was significant reduction in average number of stools per day in LGG group (P<0.001) compared to the control group. These benefits were seen irrespective of rotavirus positivity in stool tests.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Our results showed that the use of Lactobacillus GG in children with acute diarrhoea resulted in shorter duration and faster improvement in stool consistency as compared to the control group.

Keywords: Diarrhoea, Lactobacillus, probiotics

Diarrhoea is an important cause of death in children under 5 years of age in developing countries. It is responsible for about 15 per cent of the 8.79 million annual under-five deaths worldwide and ranks second to pneumonia as the major cause of mortality in children1. India contributes significantly to this global burden. Of the 1.83 million child deaths in India in 2010, 13 per cent were caused by diarrhoeal diseases alone1. Though mortality due to diarrhoea has decreased over the years, it is still unacceptably high. Randomized controlled trials in developed countries have reported benefits of Lactobacillus GG (LGG) and Saccharomyces boulardii in the treatment of acute watery diarrhoea2,3,4. This benefit is seen primarily in rotaviral diarrhoea in infants and young children2,3. Similar benefit however, was not seen with other probiotics3. Limited information is available on the potential role of Lactobacillus GG in acute diarrhoea in infants and young children living in the developing world, where diarrhoeal aetiology and gut flora are likely to be different. Basu and colleagues have reported beneficial effects of Lactobacillus GG in acute diarrhoea5,6. Our study was aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Lactobacillus GG in the treatment of acute diarrhoea in children from a semi-urban city in north India.

Material & Methods

This open label randomized controlled trial was conducted in the Department of Pediatrics at LLRM Medical College, Meerut, India, from October 2010 to March 2012. Children were eligible for the study if they were aged between 6 months to 5 years and presented with acute diarrhoea (less than 7 days duration) to the outpatient department (OPD) or pediatric emergency services. Diarrhoea was defined as passage of three or more loose stools in the last 24 hours7. Children with severe malnutrition (weight for height < 3 SD of WHO charts), dysentery (presence of visible blood in stools), clinical evidence of co-existing acute systemic illnesses (e.g. meningitis, sepsis, pneumonia) and clinical evidence of chronic disease (e.g. chronic gastrointestinal disease, chronic liver disease, chronic renal disease, nephrotic syndrome) were excluded from the study. Subjects in whom probiotics were used in the preceding three weeks or if antibiotics were used for current episode of diarrhoea, were also excluded from the study. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of LLRM Medical College, Meerut. Informed written consent was obtained from parents of children enrolled in the study. The trial was registered in Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI/2011/10/002067).

Sample size: In a previous study, mean duration of diarrhoea was 58.3 ± 27.6 hours in probiotic group and 71.9 ± 35.8 hours in placebo group8. Using this data set, it was calculated that 200 subjects were needed to be enrolled (100 subjects in each group) to detect a mean difference in duration of diarrhoea of 24 hours in the two group, with 90 per cent power and 2- tailed alpha of 0.05.

Randomization and allocation concealment: All included children were randomized to receive either Lactobacillus GG (LGG) (intervention group) or no probiotic medication (control group) using block randomization with block size of four. Sequence was generated by a person not directly involved in execution of the study. Allocation concealment was done using serially numbered sealed opaque envelopes.

Intervention: Baseline socio-demographic data were recorded and clinical examination was done as per a predesigned proforma. Baseline hydration status at the time of enrolment of every child was assessed as per WHO guidelines7. Study children were managed according to the WHO guidelines which included oral rehydration therapy (ORT) with reduced osmolarity ORS and zinc (zinc sulphate dispersible tablets) 20 mg/day for 14 days and continued feeding. Severe dehydration was managed with intravenous fluids (ringer lactate) as per WHO guidelines.

Intervention group received Lactobacillus GG (lyophilized Lactobacillus casei, strain GG) in addition to the standard management of diarrhoea. Lactobacillus GG was given as a single capsule (Culturelle Probiotic, Amerifit, USA) containing 10 billion colony forming units (cfu) per day for five days. The content of the capsules was removed and dissolved in milk (as per manufacturer's recommendations) and was then given with spoon.

All study subjects were asked to provide a stool sample in a sterile wide mouthed container; rotavirus was tested by ELISA using Rota IDEIA Kit (DAKO, Ely, UK). Other microbiological investigations were performed only if required for specific clinical reasons.

Children were monitored for number of loose stools, consistency of stool and time since last loose stool (every six hour in a day). Children were also monitored for adverse events like fever, vomiting, pain abdomen, need for admission, development of any other new symptoms and any hypersensitivity reaction like skin rashes. Children admitted in emergency ward were monitored directly by doctor on duty. Those who were enrolled on outpatient basis were contacted telephonically till diarrhoea resolved or for a period of seven days after enrolment, whichever was earlier.

Outcome measures: Primary outcome measures were duration of diarrhoea [time in hours from enrolment to the last abnormal (loose or liquid) stool] and time to change in stool consistency. Last abnormal stool was defined when the child passed normal stool or no stool for next 24 hours. Stool consistency was evaluated on a Likert Scale adapted from that used by Bliss et al9 [1-normal (having a hard or firm texture and retaining a definite shape), 2-loose (retaining same general shape in the pan; does not spread all over the pan), 3- semi-liquid (lacking any shape of its own; spreads over the pan), and 4-liquid (like water)] and improvement was recorded when there was improvement by at least one score. Secondary outcome measures were number of loose stools per day during the entire episode, duration of vomiting, duration of hospital stay and adverse effects.

Statistical analysis: Mean durations of diarrhoea, vomiting and hospital stay in the two groups were compared using unpaired t test. All proportions were compared using Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test as applicable. Data were analysed using SPSS Version 17.0 Chicago, IL. Median duration of diarrhoea and median time to improvement in stool consistency in the two groups were compared using Kaplan Meier survival analysis. Cases were censored after recording their last available record in case of loss to follow up and at seven days in case of continuing symptoms. Intention to treat analysis was used for all primary outcomes. Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to calculate hazard ratios for the primary outcome taking rotavirus status as a covariate. Hazard ratio of <1 signified benefit of intervention.

Results

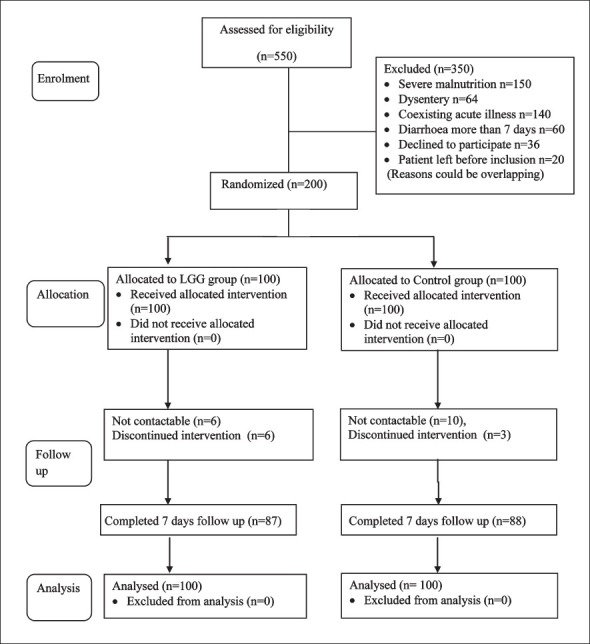

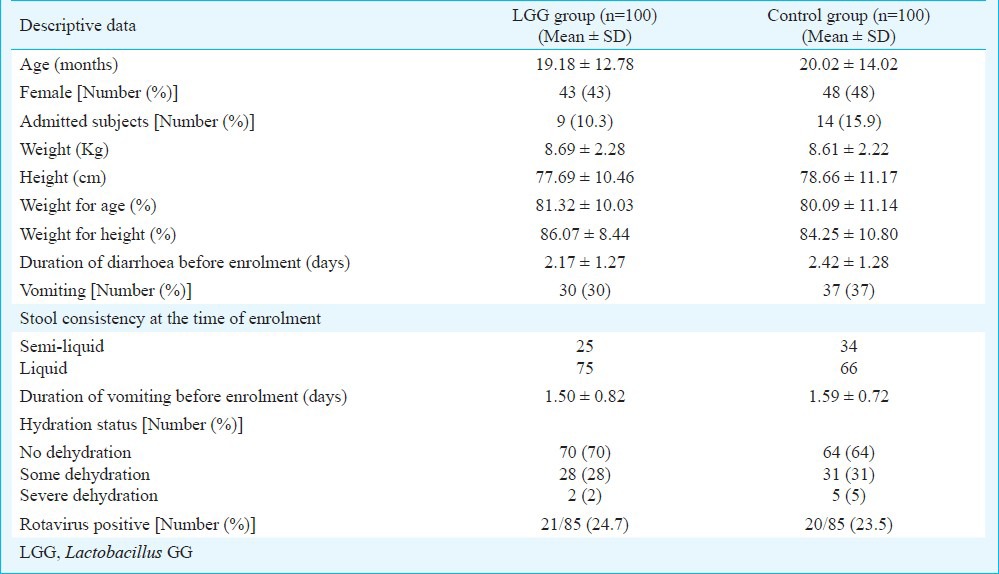

Of the 200 patients enrolled in the study, 175 (87.5%) completed the seven days follow up (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics in the two groups were comparable in age, sex and anthropometry. Duration of diarrhoea before enrolment was about two days in both groups (2.17 days in LGG group vs 2.42 days in control group). Duration of vomiting before enrolment, hydration status and rotavirus status were also comparable in both the groups (Table I). Rotavirus status could be assessed in 170 patients. Stool samples of 41 patients (24.1%) were positive for rotavirus.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of participant's enrolment in the study.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of children in the two study groups

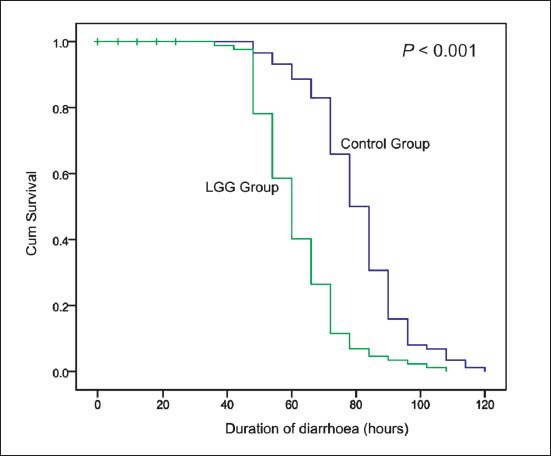

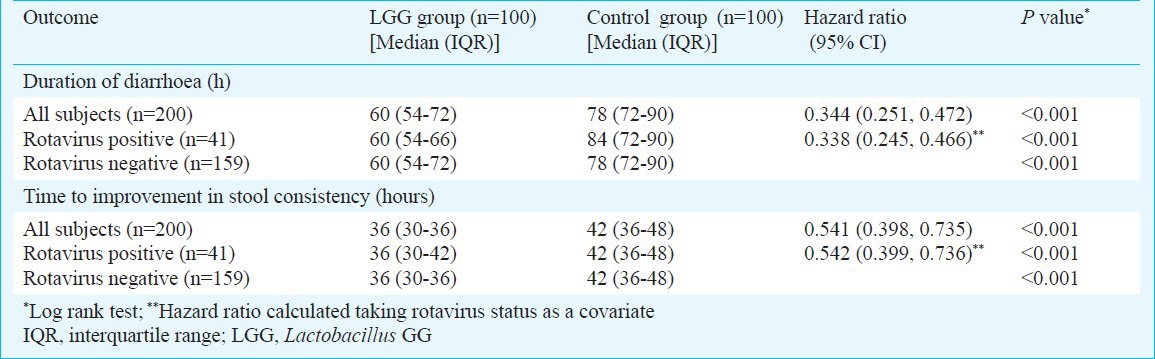

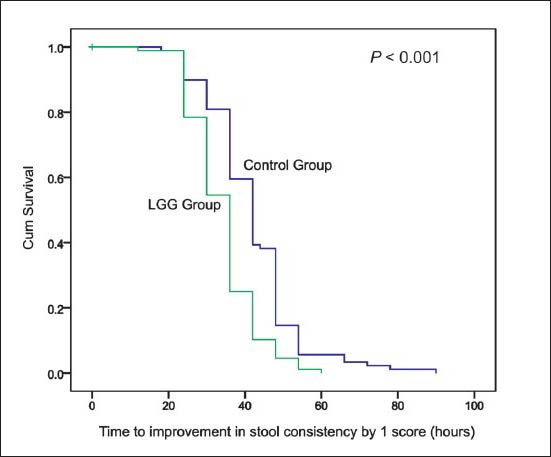

Primary outcome measures: Median duration of diarrhoea was significantly (P<0.001) lesser by about 18 h in children who received LGG in comparison to control group (Fig. 2A, Table II). There was faster improvement (P<0.001) in stool consistency by about 6 hours in the LGG group compared to control group. (Fig. 2B, Table II). The mean (95% CI) difference were 18.78 (14.64, 22.94) and 7.81 (4.77, 10.84) hours for duration of diarrhoea and time to improvement in stool consistency, respectively.

Fig. 2A.

Kaplan Meier survival analysis of duration of diarrhoea (hours).

Table II.

Primary outcome variables in the two groups

Fig. 2B.

Kaplan Meier survival analysis of time to improvement in stool consistency (hours).

The benefits on duration of diarrhoea and duration of change in stool consistency were seen both in rotavirus positive and rotavirus negative subjects (Table II). The hazard ratios for both durations did not change when rotavirus status was taken as a covariate in cox proportional hazard analysis (Table II).

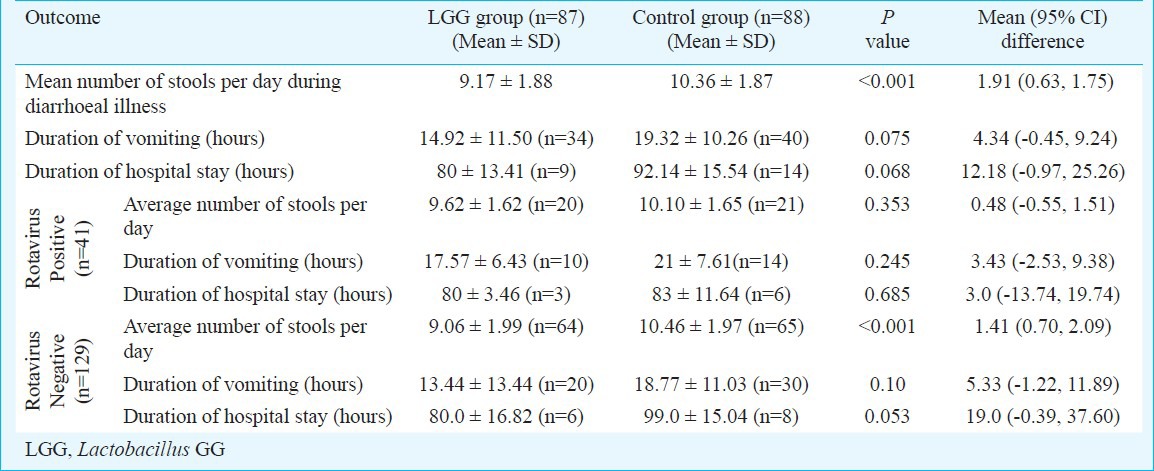

Secondary outcome measures: (i) Stool frequency: There was a significant reduction in average number of stool per day in LGG group [mean (95% CI) difference of 1.91 (0.63, 1.75) stools per day]. (ii) Effect on vomiting: There was no significant reduction in duration of vomiting in the LGG group [mean (95% CI) difference of 4.34 hours (-0.45, 9.24) hours]. (iii) Effect on duration of hospital stay: There was no significant reduction in duration of hospital stay in LGG group [mean (95% CI) difference of 12.18 hours (-0.97, 25.26) hours].

No adverse effect was noted in any group. Numbers of vomiting episodes were comparable in the LGG and control groups.

Discussion

This randomized controlled trial conducted in a semi urban setting with high background diarrhoeal rates demonstrated that Lactobacillus GG in a dose of 10 billion CFU/ day for five days given to children aged under five during an episode of acute diarrhoea results in shortening of the duration of diarrhoea and faster improvement in stool consistency and frequency. The benefits were seen irrespective of their rotavirus status.

A meta-analysis of eight randomized control trials including 988 children of 1 to 36 months, reported that LGG was associated with significant reduction in duration of diarrhoea [weighted mean difference (WMD) of -1.1 days]. Contrary to our study, which did not demonstrate any difference in the outcome in relation to rotavirus status, the meta-analysis reported maximum benefit in diarrhoea due to rotavirus (WMD of -2.1 days)12. The reason could be that most of the studies included in this meta-analysis were from developed countries, where aetiological strains and gut flora could be different.

Basu et al reported from India that Lactobacillus GG given in dose of 60 million cfu twice a day for days 7 had no beneficial effects in children with acute diarrhoea5. The absence of benefit in this study could be because of lesser dose used in their study, as another trial by the same group using LGG in dose of 10 billion cfu twice a day for days 7 reported reduction in duration and frequency of diarrhoea, and in hospital stay. They also reported that further increase in dose to 103 billion cfu twice a day did not exhibit any extra benefits6. Our study also documented the beneficial effects of LGG in dose of 10 billion cfu/day.

The benefits of Lactobacillus GG in diarrhoea could be related to competitive blockage of receptor sites,13 enhanced immune response by Lactobacilli14, transmission of signal(s) from lactobacilli to host that downregulates the secretory and motility defences designed to remove perceived noxious substance, and inactivation of viral particles15. Donato et al16 have reported that LGG alleviates the effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ on epithelial barrier integrity and inflammation, as CXCL-8 (interleukin-8) and CCL-11 (eotaxin) protein levels were decreased in LGG-inoculated, cytokine-challenged cells. It was mediated, at least in part, through inhibition of TNF-α induced nuclear factor (NF)-κB signalling.

Though other species of lactobacilli are commercially available in India, Lactobacillus GG is still not available. The results of this trial do not endorse use of other species of lactobacilli or most other probiotics species, as their effects are not similar and these have not been shown to be as effective in acute diarrhoea in children17,18.Table III

Table III.

Secondary outcome variables in the two groups

Potential limitations of this trial include its open labelled nature and lack of placebo control. Moreover, as majority of subjects were not admitted, we relied on information provided by the parents. However, we contacted our patients frequently by repeated communication at short intervals to ensure compliance and to check for outcome. Although rotavirus status was assessed in the stool samples in 170 patients, other aetiologies for acute diarrhoea were not explored and this also was a limitation. We also could not assess the 24 hour stool output. Although we monitored common clinical symptoms such as fever, vomiting, pain abdomen, development of any other new symptoms and any hypersensitivity reaction like skin rashes as potential adverse effects of intervention, we did not monitor for any asymptomatic bacteremia due to Lactobacillus GG.

To conclude, Lactobacillus GG in dose of 10 billion cfu/ day for five days given to children aged under five resulted in shortening of the duration of diarrhoea and faster improvement in stool consistency. The results are applicable for children presenting to hospital in a semi-urban setting of a developing country and may not be valid for communities. Large scale community based efficacy and effective trials are needed to confirm these results.

References

- 1.Deb AK, Kanungo S, Nair GB, Narain JP. The challenge of pneumonia & acute diarrhoea at global, regional & national levels: time to refocus on a top most priority health problem. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:128–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen SJ, Martinez EG, Gregorio GV, Dans LF. Probiotics for treating acute infectious diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;11:CD003048. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003048.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guandalini S. Probiotics for prevention and treatment of diarrhea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(Suppl):S149–53. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182257e98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riaz M, Alam S, Malik A, Ali SM. Efficacy and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii in acute childhood diarrhea: a double blind randomised controlled trial. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:478–82. doi: 10.1007/s12098-011-0573-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basu S, Chatterjee M, Ganguly S, Chandra PK. Efficacy of Lactobacilus rhamnosus GG in acute watery diarrhoea in Indian children: a randomised controlled trial. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43:837–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basu S, Paul DK, Ganguly S, Chatterjee M, Chandra PK. Efficacy of high-dose Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in controlling acute watery diarrhea in Indian children: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:208–13. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815a5780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geneva: WHO; 2005. [accessed on March 29, 2014]. World Health Organization (WHO). The treatment of diarrhoea: a manual for physicians and other senior health workers - 4th rev. WHO/COD/SER/80.2. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241593180.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guandalini S, Pensabene L, Zikri MA, Dias JA, Casali LG, Hoekstra H, et al. Lactobacillus GG administered in oral rehydration solution to children with acute diarrhea: a multicenter European trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30:54–60. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200001000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmaro Bliss D, Larson SJ, Burr JK, Savik K. Reliability of a stool consistency classification system. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2001;28:305–13. doi: 10.1067/mjw.2001.119013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canani RB, Cirillo P, Terrin G, Cesarano L, Spagnuolo MI, De Vincenzo A, et al. Probiotics for treatment of acute diarrhoea in children: randomized clinical trial of five different preparations. BMJ. 2007;335:340. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39272.581736.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guarino A, Canani RB, Spagnuolo MI, Albano F, Di Benedetto L. Oral bacterial therapy reduces the duration of symptoms and of viral excretion in children with mild diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25:516–9. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199711000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szajewska H, Skorka A, Ruszczynski M, Gieruszczak-Bialek D. Meta-analysis: Lactobacillus GG treating acute diarrhoea in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:871–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernet MF, Brassart D, Neeser JR, Servin AL. Lactobacillus acidophilus LA 1 binds to cultured human intestinal cell lines and inhibits cell attachment and cell invasion by enterovirulent bacteria. Gut. 1994;35:483–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaila ME, Isolauri E, Soppi E, Virtanen E, Laine S, Arvilommi H. Enhancement of the circulating antibody secreting cell response in human diarrhea by a human Lactobacillus strain. Pediatr Res. 1992;32:141–4. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cadieux P, Burton J, Gardiner G, Braunstein I, Bruce AW, Kang CY, et al. Lactobacillus strains and vaginal ecology. JAMA. 2002;287:1940–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.15.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donato KA, Gareau MG, Wang YJ, Sherman PM. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG attenuates interferon-{gamma} and tumour necrosis factor-alpha-induced barrier dysfunction and pro-inflammatory signalling. Microbiology. 2010;156:3288–97. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.040139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dutta P, Mitra U, Dutta S, Rajendran K, Saha TK, Chatterjee MK. Randomised controlled clinical trial of Lactobacillus sporogenes (Bacillus coagulans), used as probiotic in clinical practice, on acute watery diarrhoea in children. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:555–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanna V, Alam S, Malik A, Malik A. Efficacy of tyndalized Lactobacillus acidophilus in acute diarrhea. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:935–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02731667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]