Abstract

We present a case where an ECG and echocardiogram suggested pulmonary embolism and early treatment led to a positive outcome.

Background

Acute pulmonary embolism (PE) is often a missed and misdiagnosed disease that leads to a fatal outcome. Its diagnosis can be challenging. Risk factors can be found through careful history taking. Findings can be confirmed through the use of blood tests (such as DDimer) and imaging (ultrasounds, CT scan and ventilation perfusion scans). However, these techniques, while sensitive, often cannot be utilised. This is because of time constraints in an unstable patient, or due to pre-existing contraindications if stable. Through the use of quick bedside tools such as the ECG and echocardiogram, the diagnosis can be suggested. Our case below will highlight their appropriate utility.

Case presentation

A 65-year-old commercial truck driver with personal history of stage III chronic kidney disease and no history of cardiopulmonary problems presented to the emergency department with reports of dizziness and lightheadedness. He had been having these symptoms over the previous 2 weeks most evident when moving from sitting to standing posture. He did admit to some intermittent shortness of breath without triggering factors. He contacted the emergency medical service. They arrived to find him diaphoretic. He then had a syncopal episode lasting a few minutes. His vitals on arrival to the emergency department were stable. General and cardiopulmonary examinations were normal.

Investigations

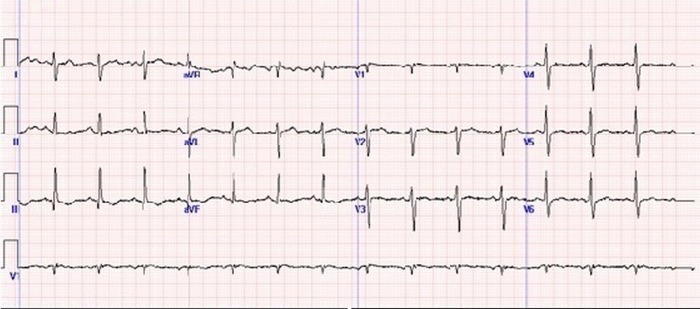

Basic metabolic profile and complete blood count were within normal limits. Troponin T was 0.083 µg/L. An ECG (figure 1) revealed sinus tachycardia with a rate of 100 bpm and a classic S wave in lead I, Q wave in lead III and inverted T wave in lead III. A bedside echocardiogram (figures 2 and 3) revealed a severely dilated right ventricle and impaired right ventricular systolic function. The right ventricular apex was spared.

Figure 1.

ECG with sinus tachycardia at 100 bpm. Also present is a S wave in lead I, a Q wave in lead III and an inverted T wave in lead III.

Figure 2.

Echocardiogram in two-chamber view demonstrating a dilated right ventricle.

Figure 3.

Echocardiogram in left parasternal long axis view demonstrating dilated right ventricle.

Differential diagnosis

Given these findings, the working differential was an acute pulmonary embolus.

Treatment

The patient was started on empiric fibrinolytic therapy and anticoagulation. Doppler ultrasound of the legs revealed an occlusive acute thrombus in the peroneal veins on the right side and acute non-occlusive thrombus in the common femoral vein, profunda femoral vein, superficial femoral vein and popliteal veins. A ventilation perfusion scan reported multiple wedge-shaped perfusion defects in the left lung and diminished activity in the lower lobe of the right lung. Ventilation images revealed homogenicity. Overall the appearance was highly probable for pulmonary embolism. Therefore, embolism had caused acute cor pulmonale.

Outcome and follow-up

Within a few hours, his clinical status improved dramatically. He was later discharged on a course of anticoagulants.

Discussion

The immediate consequence of a high-degree occlusion of the pulmonary artery is sudden right ventricular dilation. This acute cor pulmonale can be reflected as characteristic changes on the ECG and echocardiogram.

On the ECG, this presents with right axis deviation and a right heart strain pattern that can be found by early responders.

With the development of imaging techniques with higher sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of PE, interest in the use of standard ECG has decreased.

Although, sinus tachycardia is the most common abnormality,1–3 it is important to understand that there is no isolated abnormality on the ECG associated with PE. Findings may affect rate, rhythm, conduction, axis and/or morphology.

McGinn and White4 first described the S1Q3T3 pattern in 1935. Its reported incidence is from 10% to 50%.1 The S wave in lead I signifies a complete or more often incomplete right bundle branch block. The changes in lead III are a result of right heart strain and right ventricular overload. Although considered ‘pathognomic’ for PE, it is a more specific marker for any cause of acute cor pulmonale including acute bronchospasm, pneumothorax and other acute lung disorders. If pulmonary embolism is clinically suspected in the patient, the ECG becomes a quick and important bedside tool for evaluation.

The use of a bedside echocardiogram can offer vital clues towards the presence of PE. Although we acknowledge it has a low sensitivity, this does increase exponentially when dealing with a massive PE.5 The diagnostic value of an ultrasonographical combined strategy (echocardiography associated with venous ultrasonography) is high and this strategy seems to be reliable in PE. In a patient with haemodynamic compromise, an echocardiogram showing right ventricular (RV) dilation and impairment, with spared involvement of the ventricular apex is the ‘McConnell sign’. This is highly suggestive of PE. This sign is due to the following proposed mechanism.6 To counter the abrupt increase in afterload and equalise the regional wall stress, the right ventricle assumes a spherical shape. The apical sparing is secondary to its tethering to a contracting and hyperdynamic left ventricle. In a patient with shock or hypotension, the absence of echocardiographic signs of RV overload or dysfunction practically excludes PE as a cause of haemodynamic compromise. Right heart thrombi in transit can also be sometimes found on transthoracic echocardiography.7 Electively, or in non-high-risk situations (stable patients where mortality rates are low) it can offer prognostic information and risk stratify the embolism.8

The use of both the ECG and echocardiogram are therefore, important investigations in the pathway of diagnosing PE, especially if there are limits to use of more sophisticated imaging techniques by time (in unstable patients) and contraindications. With more clues suggestive of the diagnosis, decisions regarding starting effective treatment can be made sooner.

Learning points.

Acute pulmonary embolism is often missed and misdiagnosed resulting in fatal outcomes.

Acute pulmonary embolism can lead to sudden cor pulmonale, which can be reflected as characteristic changes on the ECG and echocardiogram.

The S1Q3T3 pattern on ECG is considered pathognomic.

The McConnell sign (impaired hypokinetic right ventricle and spared apex) in a haemodynamically unstable patient is suggestive of pulmonary embolism.

The aim should be to start empiric therapy as soon as possible for a positive outcome.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rodger M, Makropoulos D, Turek M, et al. Diagnostic value of the electrocardiogram in suspected pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:807–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sreeram N, Cheriex EC, Smeets JL, et al. Value of the 12 lead electrocardiogram at hospital admission in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol 1994;73:298–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spodick DH. Electrocardiographic responses to pulmonary embolism. Mechanisms and sources of variability. Am J Cardiol 1972;30:695–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGinn S, White PD. Acute cor pulmonale resulting from pulmonary embolism. JAMA 1935;104:1473 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvin JE. Pressure segment length analysis of right ventricular function: influence of loading conditions. Am J Physiol 1991;260:H1087–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janz RF, Kubert BR, Pate EF, et al. Effect of shape on pressure volume relationships of ellipsoidal shells. Am J Physiol 1980;238:H917–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casazza F, Bongarzoni A, Centonze F, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of right-sided cardiac mobile thrombi in acute massive pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:1433–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Heusel G, et al. Heparin plus alteplase compared with heparin alone in patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1143–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]