Abstract

Preeclampsia complicates 2-8% of all pregnancies and is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality and pre-term delivery in world. In concern to the increasing number of preeclamptic cases and lack of data about the interrelation between levels of trace elements and preeclampsia, we conducted a hospital based case-control study to assess the risk of preeclampsia in relation to concentrations of trace elements like copper, manganese and zinc in a hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The study consisted of 120 pregnant women divided into three groups of 40 each - control, HR group and the PET group. The serum levels of Cu, Mn and Zn were estimated by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry. Analysis of trace elements revealed that mean values of Cu, Mn and Zn were 2.01 ± 0.43, 0.125 ± 0.07 and 1.30 ± 0.83 mg/L respectively in control. In preeclamptic group, the mean values of Cu, Mn and Zn were 1.554 ± 0.53, 0.072 ± 0.06 and 0.67 ± 0.59 mg/L respectively. Levels of Cu and Zn were found to decrease significantly (P < 0.001) in preeclamptic group compared to control. Pearsons correlation analysis revealed a positive correlation between levels of Cu, Mn and Zn and systolic blood pressure. However the correlation of Cu, Mn and Zn with maternal age, gestational age, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure was statistically insignificant. In conclusion, our study suggests that preeclamptic patients have considerably lower levels of Cu, Mn and Zn compared to control and reduction in serum levels of copper, manganese, and zinc during pregnancy might be possible contributors in etiology of preeclampsia.

Keywords: Preeclampsia, copper, manganese, zinc

Introduction

Preeclampsia is a common medical complication of pregnancy standing next to hemorrhage and embolism among pregnancy related cause of death. 790 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births have been reported due to preeclampsia [1]. Its incidence in primigravidae is about 10% and in multigravidae about 5% [2]. In Saudi Arabia the incidence of preeclampsia is extrapolated to 13,876 out of a population of 25,795,938 [3]. It is a non-convulsive form of pregnancy-induced hypertension and accounts for maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality [4]. Preeclampsia when complicated with convulsion is called eclampsia. Preeclampsia occurs during second and third trimester of pregnancy and it is more common in nulliparous women. It is characterized by development of high blood pressure (hypertension) and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation and affects about 5-8% of all pregnancies. In preeclampsia the systolic BP is 140 mmHg and diastolic BP 90 mmHg in a woman with previously normal blood pressure and with proteinuria 0.3 gm in a 24-hour urine collection or equal to 1+ or 100 mg/dl by dipstick response. Severe preeclampsia is associated with one or more of elevated blood pressure 160 mmHg systolic, or 110 mmHg diastolic, on two occasions at least 6 hours apart with proteinuria > 5 g in a 24-hour urine collection [5].

Pregnancy is a period of rapid growth and cell differentiation for both the mother and fetus. Consequently, it is a period during which both are vulnerable to changes in dietary supply, especially of those micronutrients that are marginal under normal circumstances. Essential trace elements are involved in various biochemical pathways [6]. Their specific and the most important functions are the catalytic role in chemical reactions and in structural function in large molecules such as enzymes and hormones [7]. Alterations in concentrations and homeostasis of each of these micronutrients in body are well-known contributors in pathophysiology of various disorders and disease [8].

Vitamins and minerals collectively referred as micronutrients have important influence on the health of pregnant women and growing fetus [7]. The trace elements namely zinc, manganese and copper are necessary during pregnancy and these elements should be supplemented as a daily requirement in pregnant women [9]. Pregnancy is associated with increased demand of all micronutrients like Iron, copper, zinc, vitamin B12, folic acid and ascorbic acid [10]. The deficiency of these nutrients could affect pregnancy, delivery and outcome of pregnancy.

Copper is an essential trace element, which has been found to be an important constituent of vital Cu-dependent enzymes such as lysyl oxidase, cytochrome oxidase, tyrosinase, dopamine-β-hydroxylase, peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase, monoamine oxidase, ceruloplasmin, and copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (Cu-Zn SOD), functioning as antioxidants and as oxidoreductases and these enzymes act as antioxidant defense system [11]. Thus as a part of powerful antioxidant it helps to protect the cell from damage. Copper is also present in ceruloplasmin and promotes the absorption of iron from the gastrointestinal tract [12]. Copper deficiency is rare, but cases have been identified in humans, which manifested as neutropenia, anemia and skeletal abnormalities with atherogenic and electrocardiographic irregularities and is linked to low birth weight of neonates [13].

Zinc is another important trace element involved in a variety of biochemical functions in the body. It is co-factor for the synthesis of number of enzymes, DNA and RNA. Zinc is a structural component of several proteins such as growth factors, cytokines, receptors, enzymes and transcription factors which play an important role in the cellular signaling pathways. Approximately 10% of all protein in human body binds with Zn and the biological activity of these Zn bound protein depends on the concentration of Zn in the body [14]. Zinc deficiency has been associated with complications of pregnancy and delivery, as well as with growth retardation and congenital abnormalities in the fetus. Several reports had suggested that zinc deficiency may be associated with increased incidence of preeclampsia [7]. Zinc acts as an intracellular signaling molecule. Thus, alteration of Zn homeostasis and dysfunction in the signaling function of Zn may cause pathogenesis of several diseases [15].

Manganese is involved in formation of bone and cartilage. It is also a component of enzymes that play a role in the formation of carbohydrates, amino acids, and cholesterol. Manganese is found as a free element in nature (often in combination with iron), and in many minerals. It is a cofactor for a wide range of enzymes including oxidoreductases, transferases, hydrolases, lyases, isomerases, ligases, lectins, and integrins. It is also a component of the polypeptide arginase and Mn-containing superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD). As a part of a powerful antioxidant called manganese superoxide dismutase; it protects cells from oxidative injury [16].

Several evidences indicate that various elements might play important role in preeclampsia [17]. Some studies have shown that changes in the levels of blood trace elements in preeclamptic patients may implicate its pathogenesis, while others have failed to show an association of blood levels of trace elements and prevalence of preeclampsia [18-20]. Deficiencies of trace elements such as zinc, copper, selenium and magnesium have been implicated in various reproductive events like infertility, pregnancy wastage, congenital anomalies, preeclampsia, placental abruption, premature rupture of membranes, still births and low birth weight [21,22]. The exact etiology of preeclampsia is still not known. Unfortunately, there is scarcity of document discussing the circulating level of several essential trace elements in preeclampsia women of Saudi Arabia. Keeping in view with the scarcity of data concerning maternal trace metal status during pregnancy and the inconsistent findings from the few published studies to date, we conducted a hospital-based case-control study in Riyadh hospital, Saudi Arabia to assess the risk of preeclampsia in relation to concentrations of trace elements like copper, manganese and zinc. The present study was designed to contribute to a better understanding of the potential alterations of the serum levels of Cu, Mn and Zn in normal pregnant women, women at high risk of the disease and preeclamptic pregnancies. Various detection techniques including flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer (FAAS), electro thermal AAS are routinely used for analysis of trace elements. The ICP-OES (Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry) is used in the present study for estimation of trace elements for its more sensitivity, low detection limits and multi-element analysis capability. We hypothesize that changes in the status of trace elements of pregnant women may contribute to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia.

Materials and methods

Study population

This case controlled study was carried out in the Department of Clinical Laboratory Sciences, King Saud University and Section of Obstetrics and Gynecology, King Saud Medical City Hospital, Riyadh from September 2012 to December 2013. The study was approved by hospital’s ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from patients before blood sampling.

A total of 120 pregnant women were enrolled in this study and divided into three groups of 40 each- healthy normotensive pregnant women (Control group), pregnant women at high risk of preeclampsia (HR group) and women with preeclampia (PET group). All study subjects were attending antenatal OPD or labor room in their third trimester of pregnancy.

Inclusion criteria

Control group - Pregnant women with normal BP, absence of proteinuria and without any other systemic or endocrine disorder. All subjects included were in their third trimester (gestational age of ≥ 24 weeks).

High risk group - Women in high risk group were included based on the following criteria: pregnant women with body mass index (BMI) of 35 or more, with mild hypertension or those with preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, IUGR (intrauterine growth restriction) or pre-term delivery in previous pregnancies and those with family history of preeclampsia.

PET group - Selection and diagnosis of preeclamptic group was based on the definition of American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists [23].

Exclusion criteria

Patients with obesity, severe anemia or suffering from any hepatic dysfunction or dyslipidemia were excluded from the study.

Collection of blood samples and preliminary biochemical analysis

On admission, five milliliter venous blood samples were drawn from each individual participated in the study in metal free sterile vaccutainers when the patients were in the supine position. Blood samples obtained from patients attending OPD or admitted into hospital, were then kept at room temperature for 30 minutes and later centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min to extract the serum. The serum samples were stored in Eppendorf tubes at -80°C until analysis. Basic biochemical tests including Complete Blood Count and Hematocrit (Hct) concentration was measured in automated Cell Dyne 3700 analyzer and platelet count was obtained using automatic reader, STA compact, Mediserv, UK. At the time of blood collection, urine protein was measured by dipstick and was graded on a scale of 0-4+ (0, none; 1+, 30 mg/dl; 2+, 100 mg/dl; 3+, 300-1,999 mg/dl; 4+, at least 2,000 mg/dl).

Analysis of trace elements in serum

Serum trace elements were determined by ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission spectrometer, ACTIVA-S, HORIBA JOBIN, France.) Serum samples were filtered prior to the analysis in ICP-OES. 0.5 ml of serum was appropriately diluted with 1% HNO3 and 0.01% Triton × 100 (HPLC grade, Sigma Aldrich) as diluents. Different concentrations of standards (30,500 and 1000 ppb) of trace elements (Cu, Mn and Zn) were prepared from a stock solution of 1000 ppm for calibration of standard graphs. Absorbances were taken at 324.7, 257.6 and 213.8 nm for Cu, Mn and Zn respectively in ICP-OES. The concentrations of Cu, Mn and Zn in serum were expressed in mg/L.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± S.D. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software. Comparison of clinical characteristics and biochemical parameters of cases with control among the groups was performed by one way ANOVA following Holm-Sidak test. Pearsons correlation was performed to determine the relation of trace element with maternal age, gestational age, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure in preeclamptic group. Inter element relationship was performed between the trace elements studied in control and PET group by Pearsons correlation.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the subjects

The mean and standard deviation values of clinical characteristics of the control and cases are shown in Table 1. Age and hematocrit among control, HR group and PET group were not significantly different. Preeclamptic group has high gestational age compared to control and HR group. BMI of HR group (37.36 ± 9.005 kg/m2) was found to be significantly high compared to control and PET group (29.94 ± 6.05 and 35.12 ± 6.06 kg/m2 respectively). The comparison of biochemical parameters within the three groups are represented in Table 3. There was no significant difference in BMI between control and PET group.

Table 1.

Demographic and anthropometric data of study population

| Control group (n = 40) | High risk (HR) group (n = 40) | Preeclamptic group (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.20 ± 5.84 | 34.26 ± 6.69 | 31.55 ± 6.14 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.94 ± 6.05 | 37.36 ± 9.00 | 35.12 ± 6.06 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 31.17 ± 5.33 | 30.55 ± 6.33 | 33.72 ± 3.70 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 34.75 ± 4.30 | 34.48 ± 3.55 | 32.76 ± 3.71 |

| Platelet count (10^3/μl) | 266.17 ± 84.83 | 209.82 ± 47.64 | 156.65 ± 52.21 |

| sATP (mmHg) | 113.56 ± 13.93 | 124.7 ± 16.21 | 167. 0 ± 24.43 |

| dATP (mmHg) | 67.66 ± 9.38 | 74.45 ± 19.14 | 98.51 ± 11.16 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Table 3.

Comparison of the clinical characteristics between control and cases

| Control with high risk group | High risk group with Preeclampsia | Control group with Preeclampsia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| t | P | t | P | t | P | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 4.626 | < 0.001* | 3.23 | 0.003** | 1.395 | 0.16 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 0.698 | 0.48 | 2.85 | < 0.05** | 2.15 | 0.06 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 0.31 | 0.75 | 1.98 | 0.096 | 2.30 | 0.06 |

| Platelet count (10^3/μl) | 3.964 | < 0.001* | 3.741 | < 0.001* | 7.705 | < 0.001* |

| sATP (mmHg) | 2.63 | 0.01** | 10.07 | < 0.001* | 12.64 | < 0.001* |

| dATP (mmHg) | 2.16 | 0.033** | 7.66 | < 0.001* | 9.762 | < 0.001* |

| Serum albumin (g/l) | 4.04 | < 0.001* | 3.94 | < 0.001* | 7.96 | < 0.001* |

| erum copper (mg/L) | 2.16 | 0.03** | 2.20 | 0.06 | 4.36 | < 0.001* |

| Serum manganese (mg/L) | 4.05 | < 0.001* | 0.35 | 0.72 | 3.70 | < 0.001* |

| Serum zinc (mg/L) | 2.36 | 0.02** | 2.37 | 0.04** | 4.74 | < 0.001* |

P < 0.001;

P < 0.05.

The mean value of systolic arterial blood pressure (sATP) of control group and HR group was 113.56 ± 13.93 mmHg and 124.70 ± 16.21 mmHg respectively, while in PET group the sATP was 167.00 ± 24.43 mmHg. There was significant difference in the value of sATP (P < 0.05) among control and HR group, and P < 0.001 was observed between control and PET group and between HR with PET group. The diastolic arterial blood pressure (dATP) was found to be high in PET group (98.51 ± 11.16) compared to control and HR group (67.66 ± 9.38 and 74.45 ± 19.14, respectively). We observed a significant difference in dATP between control and PET, HR and PET group (P < 0.001) and significant difference between control and HR group (P < 0.05). In contrast to this, platelet count was found to decrease significantly (P < 0.001) in PET group compared to control and HR group.

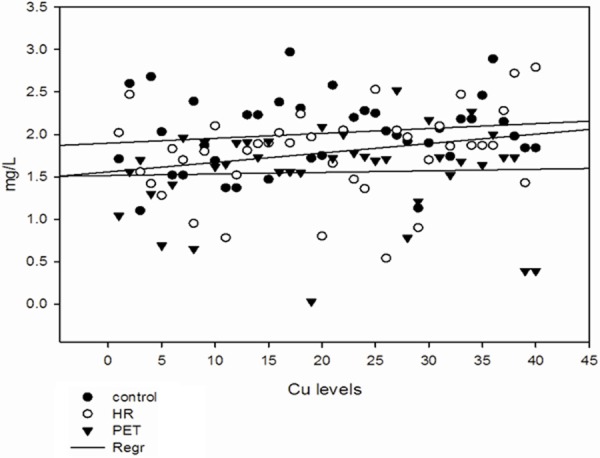

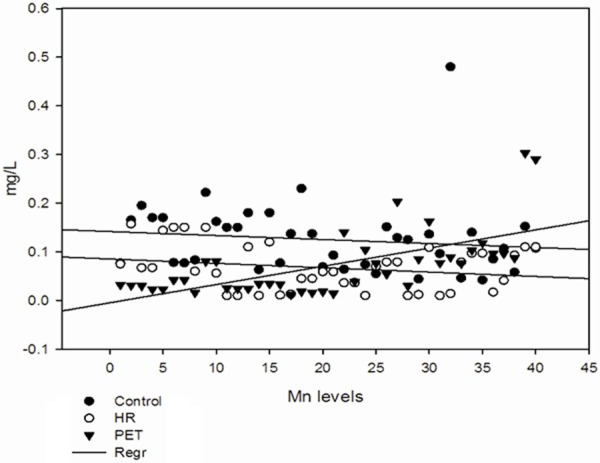

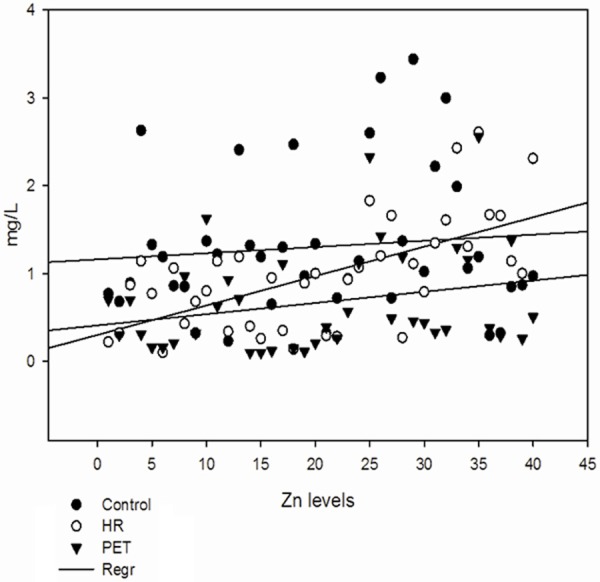

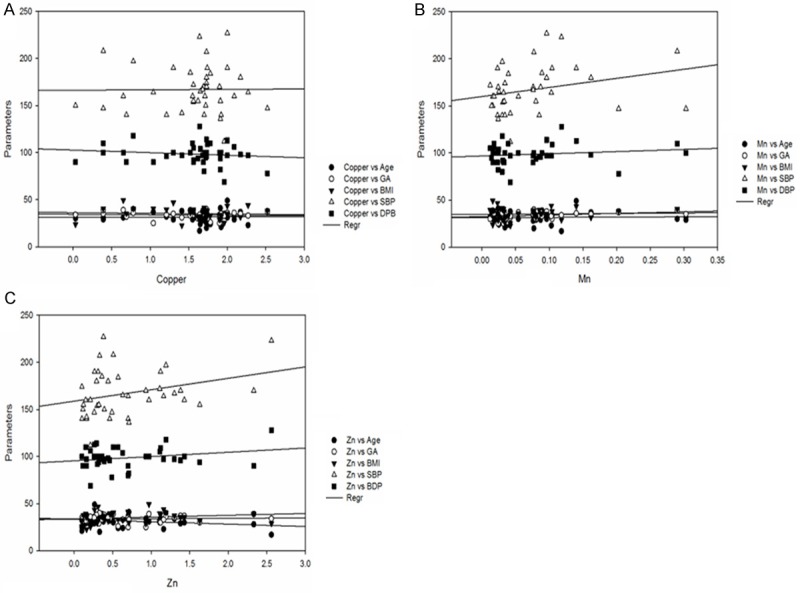

Serum levels of trace elements

Levels of serum trace elements in control, HR and Preeclamptic group are shown in Table 2. Analysis of trace elements found that mean values of Cu, Mn and Zn were 2.01 ± 0.43, 0.125 ± 0.07 and 1.30 ± 0.83 mg/L respectively in control group and 1.78 ± 0.51, 0.066 ± 0.04 and 0.98 ± 0.63 mg/L respectively in HR group. In preeclamptic group the mean values of Cu, Mn and Zn were 1.554 ± 0.53, 0.072 ± 0.06 and 0.67 ± 0.59 mg/L respectively. The levels of Cu were found to be decrease significantly (P < 0.001) in preeclamptic group compared to control. There was significant change in levels of Cu when HR group was compared to control. There was no significant change observed between HR and PET group. Similar to Cu, levels of Mn was also found to decrease significantly (P < 0.001) in PET and HR group compared to control. However, the levels of Mn between HR and PET were insignificant. Like serum Cu and Mn, levels of Zn were also found to decrease significantly (P < 0.001) in PET group compared to control and (P < 0.05) was observed between control and HR group and between HR and PET group (Figures 1, 2 and 3). The data was further analyzed by pearsons correlation in order to determine the effect of maternal age, gestational age, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure on serum trace elements in preeclamptic group (Table 4, Figure 4A-C). Gestational age and BMI was positively correlated with Mn and Zn in preeclampsia patients. We observed a positive correlation between sATP with trace elements (Cu, Mn and Zn) and between dATP, Mn and Zn. On contrary, negative association was observed between dATP and copper.

Table 2.

Serum levels of Calcium, Magnesium and Zinc in study population

| Control group (n = 40) | High risk (HR) group (n = 40) | Preeclamptic group (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Copper (mg/L) | 2.014 ± 0.43 | 1.786 ± 0.51 | 1.554 ± 0.53 |

| Serum Manganese (mg/L) | 0.125 ± 0.077 | 0.066 ± 0.046 | 0.072 ± 0.068 |

| Serum Zinc (mg/L) | 1.30 ± 0.83 | 0.98 ± 0.63 | 0.67 ± 0.59 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Figure 1.

Serum levels of copper in all the groups.

Figure 2.

Serum levels of manganese in all the groups.

Figure 3.

Serum levels of zinc in all the groups.

Table 4.

Correlation of gestational age, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure with trace elements

| Copper | Manganese | Zinc | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| r (P value) | r (P value) | r (P value) | |

| Age (years) | 0.012 (0.93) | 0.033 (0.83) | -0.24 (0.13) |

| Gestational age (weeks) | -0.065 (0.68) | 0.313 (0.04)** | 0.071 (0.66) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | -0.063 (0.69) | 0.058 (0.71) | 0.187 (0.24) |

| sATP (mmHg) | 0.009 (0.95) | 0.270 (0.09) | 0.295 (0.064) |

| dATP (mmHg) | -0.132 (0.41) | 0.144 (0.37) | 0.242 (0.13) |

p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Correlation between levels of copper, manganese and zinc with BMI, gestational age, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure in preeclampsia group.

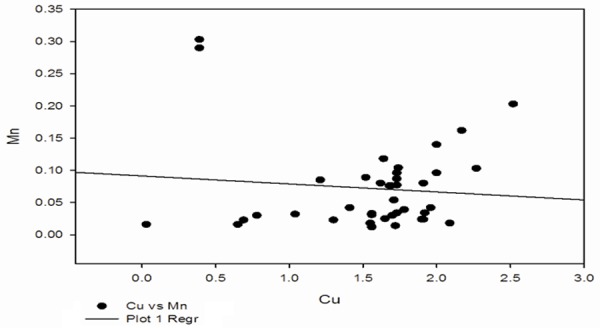

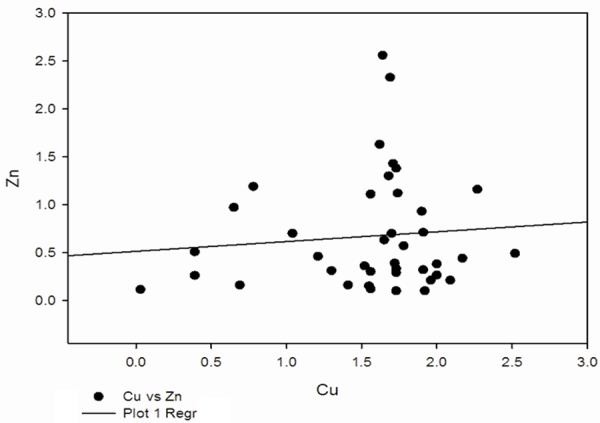

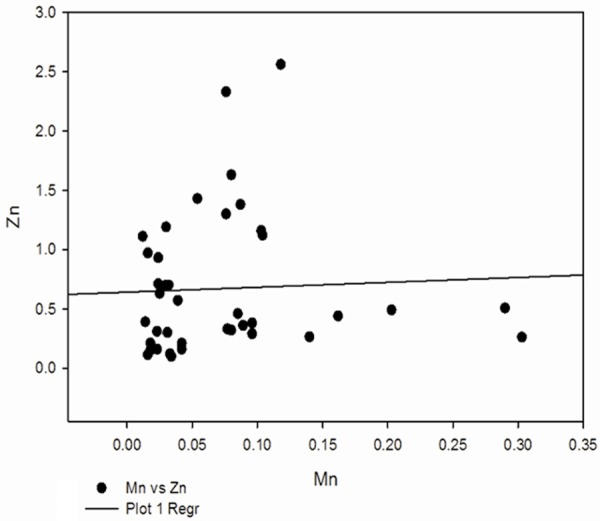

Inter-element correlations in control and preeclamptic group

Inter-element correlation for the analyzed elements in control and preeclamptic group was performed using pearsons correlation and represented in Table 5. There was positive association between Cu and Zn and between Mn and Zn in PET group (Figures 5, 6 and 7). However, the inter-element correlation were statistically insignificant (P > 0.05) in preeclamptic group.

Table 5.

Comparison of Inter-element relationship between trace elements in control and PET group

| Correlation parameters | Control group | PET group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| r | P value | r | P value | |

| Cu and Mn | -0.14 | 0.35 | -0.09 | 0.55 |

| Cu and Zn | -0.06 | 0.69 | 0.09 | 0.57 |

| Mn and Zn | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.047 | 0.77 |

Figure 5.

Correlation between Cu and Mn in preeclampsia group.

Figure 6.

Correlation between Cu and Zn in preeclampsia group.

Figure 7.

Correlation between Zn and Mn in preeclampsia group.

Discussion

Preeclampsia is a multisystem and multifactorial disease that affects both mother and fetus by vascular dysfunction and by intrauterine growth restriction [24]. In pregnancy, the processes of implantation, proliferation, differentiation and trophoblast invasion produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), while in preeclampsia, lipid peroxidation also yielding ROS is uncontrolled. It is thought that preeclampsia is associated with an imbalance of increased lipid peroxides and decreased antioxidants [25]. Placental oxidative stress has been shown to be a key feature in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Although many pathophysiological factors have been implicated in the etiology of preeclampsia, its etiology is still under investigation. A number of studies conducted to know the relationship between maternal plasma trace elements level and preeclampsia, have been reported inconsistently [26]. Some reports concluded with the changes in concentrations of blood trace elements in preeclampsia but the other did not find any association between serum trace elements and occurrence of preeclampsia [27-29]. Previous studies of maternal trace metal status for preeclamptic and normotensive patients have been inconsistent. Prior studies have predominately been limited to residents of Europe, Australia, New Zealand, North America, and China. Results from our study, therefore, add to the body of evidence concerning maternal trace metal status in preeclamptic and normotensive pregnancies in women of Saudi Arabia. Due to increase number of preeclampsia cases in Saudi Arabia women and also to add better understanding of the role of trace elements in pathogenesis of preeclampsia, the present study was undertaken to analyze the serum trace element levels like copper, Manganese and Zinc in serum of high risk group and the preeclamptic patients of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

High maternal BMI is associated with large number of pregnancy-related complications such as preeclampsia, pre-term and post-term delivery, and postpartum hemorrhage [30,31]. Although studies reported that obese women are at increased risk for developing preeclampsia and women with greater BMI in pregnancy are more likely to become hypertensive than those with lower BMI. The comparable BMI, gestational age observed in PET and the control group in the present study ruled out the influence of these parameters on the etiology or severity of preeclampsia. In this study, systolic and diastolic blood pressures were normal in the control group, but both were very high in the preeclampsia group. That is one of the symptoms of preeclampsia and there was a significant difference for both systolic and diastolic blood pressures between the patient and control groups (P < 0.001). This confirms an earlier investigation with minor changes which may due to ethnic differences [32].

In this case control study on Saudi Arabian preeclamptic pregnant women, we observed significantly (P < 0.001) lower levels of Copper in the preeclamptic women as compared to the healthy controls. Our results were consistent with that of earlier studies [33-35]. Copper is known to be a component of numerous enzymes and a cofactor of the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase [36]. Gurer et al. reported increased malondialdehyde and decreased ceruloplasmin activity in the plasma of preeclamptic women [37]. Based on these observations, low levels of copper in preeclamptic women may be associated with impairment of the cell antioxidant capacity and oxidant/antioxidant balance. In the high risk group included in the present study, the copper levels were however not found to be significant compared to preeclamptic group although there were significant changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure between the HR and PET group.

Manganese and zinc are both required for the proper functioning of enzymes like superoxide dismutase, which is required for scavenging free radicals. Deficient concentrations of these elements during pregnancy may cause impairment of antioxidant potential of cells by decreasing superoxide dismutase activity, as well as increased lipid peroxidation, leading to increase in blood pressure [38]. Similar to copper, serum levels of manganese was also found to decrease in preeclamptic group (P < 0.001) compared to control. Several studies reported that low level of manganese in serum may cause accumulation of superoxides which could consequently trigger preeclampsia and its complications [39,40]. Thus, significant depletion of serum level of manganese (P < 0.05) as reported in the current study may trigger the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Our results are in concordance with earlier findings [21,41]. A distinct involvement of low serum manganese concentration in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia is in the impairment of endothelial function. Arginine which is the precursor of the key determinant of endothelial function contains manganese as an active component [40]. Thus, reduction in serum manganese concentration in the blood of preeclamptic pregnant women as reported in the current study may be more of a cause than a resultant effect. In contrast to our findings, Ohad et al reported higher levels of Cu and Zn in preeclampsia cases [41].

Previous studies have suggested that alterations in maternal serum or plasma Zn levels are found in preeclampsia [42]. We found significantly lower levels of Zn in the preeclamptic group when compared to control. Similar results were obtained by earlier reports [43-45]. Hypozincemia is related to hemodilution, increased urinary excretion and the transfer of this mineral from mother to the growing fetus. In pregnant women with preeclampsia, low serum zinc may be partly due to reduced concentrations of transport proteins and estrogen caused by increased lipid peroxidation. In the preeclamptic women, the lowered serum concentrations of Zn have been suggested to be at least partly the result of reduced estrogen and Zn-binding protein levels [46]. In addition, the Zn deficiency causes an increase in lipid peroxidation [47].This leads us to hypothesize that zinc may play a role in preeclampsia through an increase of lipid peroxidation.

In our study we observed positive correlation between age, gestational age, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure with Cu, Mn and Zn in the preeclamptic group. The correlations however were found to be non-significant except the correlation between gestational age and the levels of Mn. There was positive correlation between systolic blood pressure and all the three elements studied. These results are in contrast to that reported by Akhtar et al, where they observed that Zn exhibited significant negative correlation with systolic and diastolic blood pressure in preeclamptic group [48]. Also, the inter-element analysis yielded non-significant correlation suggesting the independent role of these trace elements in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia.

From the findings of the present study, it was observed that there was significant decrease in concentration of all the trace elements when compared to control group (P < 0.05). Although these findings provide a role of zinc, copper and manganese in the development and pathogenesis of preeclampsia, this result must be interpreted with caution as we did not investigate the dietary intake of preeclamptic women to find out whether the reduced levels of trace elements arise from nutritional deficiencies or not.

In conclusion, the results on the whole suggest that preeclamptic pregnant women of Saudi Arabia have lower levels of serum trace elements (copper, manganese and zinc) compared to healthy pregnant females. There has been an increasing prevalence in the incidence of preeclampsia globally but there are conflicting reports on the relationship between trace elements and preeclampsia. It is hoped that this study will contribute to the knowledge of the role of trace elements in pathogenesis of preeclampsia.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Research Center of the ‘Center for Female Scientific and Medical Colleges’, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University for the grant and the Management, King Saud Medical City Hospital, Riyadh, K.S.A for providing samples and facilities for completion of the study and Dr. Mir Naiman Ali (Assistant Professor, Mumtaaz College, India) and Dr. Mohammed Abdul Quadeer (Research Scientist, Cytocare Technologies Private Limited, India) for the statistical analysis.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Wagner LK. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:2317–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semenovskaya Erogut M, editor. Pregnancy, preeclampsia. [Cited January 17, 2014]: Available from http://medicine.medscape.com/article/796690-overview.

- 3.Statistic by country. http://www.rightdiagnosis.com/p/preeclampsia/stats-country.htm [Cited January, 2014]

- 4.Vanderjagt DJ, Patel RJ, El-Nafaty AU, Melah GS, Crossey MJ, Glew RH. High density lipoprotein and homocysteine levels correlate inversely in preeclamptic women in northern Nigeria. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:536–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2004.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray JG, Diamond P, Singh G. CM Bell. Brief overview of maternal triglycerides as a risk factor for preeclampsia. BJOG. 2006;113:379–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mertz W. The essential trace elements. Science. 1981;213:1332–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.7022654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black RE. Micronutrients in pregnancy. Br J Nutr. 2001;85:S193–197. doi: 10.1079/bjn2000314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ulmer DD. Trace elements. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:318–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197708112970607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AMA Nutrition Advisory Group. Guideline for Essential Trace Elements Preparation for Parinatal Use. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1979;3:263–269. doi: 10.1177/014860717900300411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naeye R, Blane W, Paul C. Effects of Maternal Nutrition on Human Fetus. Pediatrics. 1973;52:494–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaiser SR, Winston GP. Copper deficiency myelopathy: Review. J Neurol. 2010;257:869–81. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5511-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziael S, Ranjkesh F, Faghihzadeh S. Evaluation of 24-hourcopper in pre-eclamptic vs normotensive pregnant and nonpregnant women. Int J Fertil Steril. 2008;2:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giles E, Doyle LW. Copper in extremely low-birth weight or very preterm infants. Am Acad Pediatr. 2007;8:159–64. [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO trace elements in human nutrition and health. Geneva: WHO Press; 1996. pp. 72–104. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frederickson CJ, Koh J, Bush AI. The neurobiology of zinc in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:449–462. doi: 10.1038/nrn1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begum R, Begum A, Bullough CH, Johanson RB. Reducing maternal mortality from eclampsia using magnesium sulphate. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;92:222–223. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(99)00274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain S, Sharma P, Kulsheshtha S, Mohan G, Singh S. The Role of Calcium, Magnesium, and Zinc in Preeclampsia. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2010;133:162–70. doi: 10.1007/s12011-009-8423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bringman J, Gibbs C, Ahokas R. Differences in serum calcium and magnesium between gravidas with severe preeclampsia and normotensive controls. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:148. [Google Scholar]

- 19.James DK, Seely PJ, Weiner CP, Gonlk B. High risk pregnancy: managementoptions. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevir Sauders; 2006. p. 925. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caughey AB, Stotland NE, Washington AE, Escobar GJ. Maternal ethnicity, paternal ethnicity and parental ethnic discordance: predictors of preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:156–161. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000164478.91731.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahomed K, Williams MA, Woelk GB, Mudzamiri S, Madzime S, King IB, Bankson DD. Leckocyte selenium, zinc and copper concentrations in preeclampsia and normotensive pregnant women. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2004;75:107–118. doi: 10.1385/BTER:75:1-3:107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmeyr GT, Duley L, Atallah A. Dietary calcium supplementation for prevention of preeclampsia and related problems: a systematic review and commentary. BJOG. 2007;114:933–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noura AJ, Tabassum H, Farah AK, Ansar S, Ali MN. Relationship between dietary factors and risk of Preeclampsia: A Systematic review. South Asian J Exp Biol. 2013;3:01–09. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rumiris D, Purwosunu Y, Wibowo N, Farina A, Sekizawa A. Lower rate of preeclampsia after antioxidant supplementation in pregnant women with low antioxidant status. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2006;25:241–53. doi: 10.1080/10641950600913016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harma M, Harma M, Kocyigit A. Correlation between maternal plasma homocysteine and zinc levels in preeclamptic women. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2005;104:97–105. doi: 10.1385/BTER:104:2:097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akther R, Rashid M. Is low level of serum ionized magnesium responsible for eclampsia? J BD Coll Phys Surg. 2009;27:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ilhan N, Simsek M. The changes of trace elements, malondialdehyde levels and superoxide dismutase activities in pregnancy with or without preeclampsia. Clin Biochem. 2000;35:393–397. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(02)00336-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golmohammad S, Amirabi A, Yazdian M, Pashapour N. Evaluation of serum calcium, magnesium, copper and zinc levels in women with preeclampsia. Iran J Med Sci. 2008;33:231–234. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mbah AK, Kornosky JL, Kristensen S, August EM, Alio AP, Marty PJ, Belogolovkin V, Bruder K, Salihu HM. Super-obesity and risk for early and late preeclampsia. BJOG. 2010;117:997–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villamor E, Cnattingius S. Interpregnancy weight change and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1164–1170. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69473-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Genc H, Uzun H, Benian A, Simsek G, Gelisgen R, Madazli R, Guralp O. Evaluation of oxidative stress markers in first trimester for assessment of pre-eclampsia risk. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:1367–1373. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-1865-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumru S, Aydin S, Simnek M, Sahin K, Yaman M, Ay G. Comparison of Serum Copper, Zinc, Calcium, and Magnesium Levels in Preeclamptic and Healthy Pregnant Women. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2003;94:105–12. doi: 10.1385/BTER:94:2:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ugwuja E, Akubugwo E, Ibiam UA, Obidoa O. Impact of Maternal Copper and Zinc Status on Pregnancy Outcomes in a Population of Pregnant Nigerians. Pak J Nutrition. 2010;9:678–682. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Acikgoz S, Harma M, Harma M, Mungan G, Can M, Demirtas S. Comparison of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme, Malonaldehyde, Zinc, and Copper Levels in Preeclampsia. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2006;113:1–8. doi: 10.1385/BTER:113:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prohaska JR, Brokate B. Lower copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase protein but not mRNA in organs of copper-deficient rats. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;393:170–176. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gurer OH, Ozgunes H, Beksac MS. Correlation between plasma malondialdehyde and ceruloplasmin activity values in preeclamptic pregnancies. Clin Biochem. 2001;34:505–506. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(01)00238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thakur S, Gupta N, Kakkar P. Serum copper and zinc concentrations and their relation to superoxide dismutase in severe malnutrition. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:742–744. doi: 10.1007/s00431-004-1517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hofmeyr GT, Duley L, Atallah A. Dietary calcium supplementation for prevention of pre-eclampsia and related problems: a systematic review and commentary. BJOG. 2007;114:933–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lou GS, Amirabi A, Yazdian M, Pashapour N. Evaluation of serum calcium, magnesium, copper and zinc levels in women with pre-eclampsia. Iran J Med Sci. 2008;33:231–234. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohad K, Tal OP, Lazer T, Tamir BA, Mazor M, Witnitzer A, Sheiner E. Severe preeclampsia is associated with abnormal trace elements concentrations in maternal and foetal blood. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:280–281. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Apgar J. Zinc and reproduction. Ann Rev Nutr. 1985;5:43–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.05.070185.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adeniyi AFF. The implication of hypozincemia in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1987;66:579–581. doi: 10.3109/00016348709022059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chisolm JC, Handorf CR. Zinc, cadmium, metallothionein, and progesterone: do they participate in the etiology of pregnancy induced hypertension? Med Hypotheses. 1985;17:231–242. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(85)90128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diaz E, Halhali A, Luna C, Diaz L, Avila E, Larrea F. Newborn birth weight correlates with placental zinc, umbilical insulin-like growth factor I, and leptin levels in preeclampsia. Arch Med Res. 2002;33:40–47. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(01)00364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bassiouni BA, Foda FI, Rafei AA. Maternal and fetal plasma zinc in preeclampsia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1979;9:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(79)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yousef MI, El Hendy HA, El-Demerdash FM, Elagamy EI. Dietary zinc deficiency induced-changes in the activity of enzymes and the levels of free radicals, lipids and protein electrophoretic behavior in growing rats. Toxicology. 2002;175:223–234. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akhtar S, Begum S, Ferdousi S. Calcium And Zinc Deficiency In Preeclamptic Women. J Bangladesh Soc Physiol. 2011;6:94–99. [Google Scholar]