Abstract

Background: Ki67 index is one of the most important immunocytochemical markers of proliferation in tumors, but the criterion of Ki67 index in GISTs was not well-defined yet. Our study aims to fully evaluate the prognostic value of Ki67 index in GIST patients and efficiency of imatinib adjuvant therapy. Methods: Clinicopathological data were confirmed by pathological diagnosis and clinical recorders. Recurrence-free survivals (RFS) were evaluated in 418 GIST patients (370 cases only taken the surgery and 48 high-risks taken imatinib adjuvant therapy after R0 resection). Results: Two cutoff levels of Ki67 index (> 5 and > 8%) were established in our study through statistical analysis. Ki67 index (≤ 5, 6-8 and > 8%) is an independent prognostic factor for RFS of GIST patients. Ki67 index > 8% can precisely sub-divide high-risk GISTs effectively with different outcomes, and high-risk patients with Ki67 index > 8% showed a poorer prognosis even with imatinib adjuvant therapy. Conclusion: Ki67 index is an effective complementation of modified NIH criteria in predicting the prognosis of GISTs, and Ki67 index > 8% may act as an unfavorable factor for imatinib adjuvant therapy.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, Ki67, prognosis, targeted therapy

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) accounts for more than 80% of all gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors [1]. As it ranks below only gastric and colorectal cancers, GIST is among the most common types of gastrointestinal tumors. Recently, the incidence of GIST has gradually increased [2-4] and there are more than 5000 newly diagnosed cases each year since 2011 in the United States [5].

Modified NIH criteria based on NIH consensus criteria is wildly accepted as risk-stratification scheme for GIST and four categories from very low to high risk are used to predict prognosis of GIST patients. The mitosis count, tumor size, tumor site and tumor rupture are important prognostic predictors in this scheme [6,7]. However, the clinical behaviors and outcomes of GISTs still vary, especially in the patients with high-risk of recurrence. With wide application of imatinib mesylate (IM) in clinical practice for high-risk GISTs, the mortality rate of GIST patients has decreased significantly [8]. Nevertheless, the recurrence and metastasis rates still remain high [8-10].

Human nuclear cell proliferation-associated antigen Ki67, which is one of the most important immunocytochemical markers of proliferation, was already accepted in clinical for predicting prognosis of breast cancer or neuroendocrine tumors [11-14]. Ki67 was also demonstrated as a prognostic predictor in GISTs [15-17], but the criterion of Ki67 index in GISTs was still not well-defined compared with its in breast cancer, which affect the further analysis of the correlation between Ki67 and GISTs, and limit the clinical reference and applicative value. Our retrospective study based on 418 GIST patients (370 cases only taken the surgery and 48 high-risks taken imatinib adjuvant therapy after R0 resection), aims to fully evaluate the prognostic value of Ki67 index in GIST patients and efficiency of imatinib adjuvant therapy.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

The patient inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) a distinct pathologic diagnosis of GIST; 2) underwent R0 resection; 3) no radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other anti-cancer therapies prior to surgery; and 4) availability of complete clinicopathologic and follow-up data; 5) obtained written informed consent and approval of the ethics committee of Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine for the use of samples, approval No. 2012031. The database comprised of parameters that included patient age, gender, tumor site, tumor size, and number of mitoses/50 high-power fields (HPF). The risk of aggressive tumor behavior was calculated according to the modified NIH criteria, which classified GISTs into very low, low, intermediate, and high-risk categories.

418 paraffin-embedded tissue samples met the criteria were collected from GIST patients (370 cases only taken the surgery and 48 high-risk GISTs taken imatinib adjuvant therapy after R0 resection) at Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine from 2004 to 2013 For tissue microarray and immunohistochemical staining.

370 GIST cases without imatinib adjuvant therapy included 199 male and 171 female patients with a median age of 59 years; these included 32 very low-risk cases, 152 low-risk cases, 62 intermediate-risk cases, and 124 high-risk cases. The patients were followed up for 8 to 106 months with a median follow-up period of 42 months.

The criterion of imatinib adjuvant therapy after R0 resection in our study required at least 12 months uninterrupted drugs taking with 400 mg/day. 48 high-risk cases met the criteria of imatinib adjuvant therapy since 2008 in our study. The follow-up median of the patients with imatinib therapy was 38 months (range, 16-71 months); KIT and PDGFR gene analysis showed 45 cases with KIT 11 exon mutation and 3 cases with 9 exon mutation.

Tissue microarray construction

Tissue microarrays were constructed by Suzhou Xinxin Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Xinxin Biotechnology Co, Suzhou, China). Tissue paraffin blocks of GIST samples from 418 cases were stained with hematoxylin-eosin to confirm the diagnoses and marked at fixed points with most typical histological characteristics under a microscope. Two 1.6-mm cores per donor block were transferred into a recipient block tissue microarrayer, and each dot array contained fewer than 160 dots. Three-micron-thick sections were cut from the recipient block and transferred to glass slides with an adhesive tape transfer system for ultraviolet cross linkage.

Immunohistochemistry

The slides were ba-ked at 56°C for 1 h, de-paraffinized in xylene for 20 min, and rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol concentrations (5 min in 100% ethanol followed by 5 min in 70% ethanol). Antigen retrieval was performed in a pressure cooker for 5 min with Target Retrieval Solution (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using a peroxidase blocking reagent (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) for 5 min. Next, an monoclonal antibody against Ki67 (clone MIB-1, 1:200 dilution, Dako, Denmark) was applied to cover the specimens for 1 h at room temperature, and this was followed by incubation with a labeled polymer-HRP goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. Thorough rinsing with Tris-Buffered Saline and Tween 20 was performed after this incubation. The slides were visualized using diaminobenzidine substrate-chromogen (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) and washed with deionized water before hematoxylin counterstaining. The slides were then dehydrated through a upstaging series of ethanol concentrations, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped with Digital Picture Exchange mounting medium (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

MIB-1 staining for Ki67 was examined with 4x and 10x object lenses to identify the area of most intense staining (“hot spot”). Scoring Ki67 was performed by counting at least 500 tumor cells in high-power fields with a 40x object lens. All brown-stained nuclei, regardless of staining intensity, were counted as positive.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows (version 17.0) and MedCalc (version 11.4.2.0). For comparisons, one-way analyses of variance and chi-squared tests were performed when appropriate. RFS was calculated according to the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare the survival distributions. Univariate and multivariate analyses were based on the Cox proportional hazards regression model. Only variables that were significantly different in univariate analysis were entered into the next multivariate analysis. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were constructed to assess sensitivity, specificity, and respective areas under the curves (AUCs) with 95% CI. All statistical tests were 2-sided. P-value differences < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The optimum cut off value for diagnosis was investigated by maximizing the sum of sensitivity and specificity and minimizing the overall error (square root of the sum [1-sensitivity]2 + [1-specificity]2), and by minimizing the distance of the cutoff value to the top-left corner of the ROC curve. All statistical tests were 2-sided. P-value differences < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Ki67 index is an independent prognostic factor for RFS of GIST patients

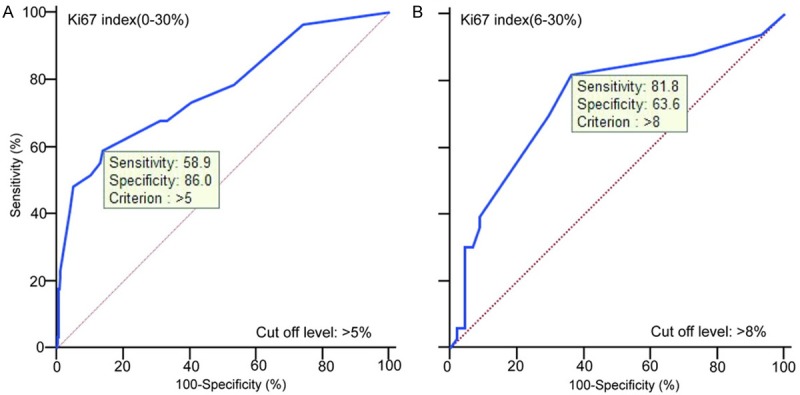

By analysis of 370 cases, the counting range of Ki67 index was 0-30% and the median was 2%. Two optimum cutoff levels were adopted in our study. The first cutoff level of Ki67 > 5% was estimated as the optimum cutoff level of total Ki67 index (0-30%) with a sensitivity of 58.9% and specificity of 86.0%; the second cutoff level of Ki67 > 8% as the optimum cutoff level of relatively “high risk” Ki67 index (6-30%) with a sensitivity of 81.8% and specificity of 63.6% (Figure 1). The optimum cutoff level of Ki67 index (0-5%) was unavailable through the statistical analysis. So we got three groups of GIST patients (Ki67 index ≤ 5, 6-8 and > 8%) divided by two cutoff levels in this study.

Figure 1.

Optimal cutoff levels of Ki67 index in GISTs from counting range 0-35% (A) and 6-35% (B).

Characteristics of 370 GIST patients were shown in Table 1. Univariate analysis showed that gender, tumor site, tumor size, mitosis count and ki67 index were prognostic predictors for RFS in GIST patients (Table 2). Furthermore, multivariate analysis found that tumor size, mitosis count and Ki67 index were independently unfavorable prognostic factors for RFS (Table 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 370 GIST patients divided by Ki67 index

| Ki 67 index (%) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| ≤ 5 | 6-8 | > 8 | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤ 50 | 62 | 2 | 9 | 0.118 |

| > 50 | 232 | 31 | 34 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 152 | 17 | 30 | 0.082 |

| Female | 142 | 16 | 13 | |

| Tumor site | ||||

| Stomach | 175 | 21 | 15 | 0.030* |

| Small bowel | 77 | 8 | 17 | |

| Colon | 16 | 0 | 2 | |

| Others | 26 | 4 | 9 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||

| ≤ 2.0 | 36 | 0 | 0 | < 0.001** |

| 2.1-5.0 | 147 | 11 | 3 | |

| 5.1-10.0 | 79 | 15 | 19 | |

| > 10.0 | 32 | 7 | 21 | |

| Mitoses per 50 HPFs | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 262 | 23 | 8 | < 0.001** |

| 6-10 | 20 | 4 | 18 | |

| > 10 | 12 | 6 | 17 | |

| Modified NIH criteria | ||||

| Very low risk | 32 | 0 | 0 | < 0.001** |

| Low risk | 141 | 10 | 1 | |

| Intermediate risk | 55 | 6 | 1 | |

| High risk | 66 | 17 | 41 | |

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01.

Table 2.

Univariate analyses of factors associated with RFS in GISTs

| Variable | RFS hazard ratio (95% Cl) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (≤ 50, > 50) | 1.438 (0.704-2.938) | 0.319 |

| Gender (male, female) | 0.424 (0.237-0.757) | 0.004** |

| Tumor site (stomach, intestinal, colon, others) | 1.745 (1.369-2.182) | < 0.001** |

| Tumor size (≤ 2, 2-5, 6-10, > 10 cm) | 3.944 (2.740-5.676) | < 0.001** |

| Mitosis count (≤ 5, 6-10, > 10/50 HPF) | 3.884 (2.907-5.188) | < 0.001** |

| Ki67 index (≤ 5, 6-8, > 8%) | 3.289 (2.464-4.390) | < 0.001** |

P < 0.01.

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses of factors associated with RFS in GISTs

| Variable | RFS hazard ratio (95% Cl) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (male, female) | 0.570 (0.317-1.023) | 0.06 |

| Tumor site (stomach, intestinal, colon, others) | 1.194 (0.952-1.498) | 0.125 |

| Tumor size (≤ 2, 2-5, 6-10, > 10 cm) | 2.363 (1.586-3.522) | < 0.001** |

| Mitosis count (≤ 5, 6-10, > 10/50 HPF) | 2.146 (1.475-3.123) | < 0.001** |

| Ki67 index (≤ 5, 6-8, > 8%) | 1.469 (1.031-2.094) | 0.033* |

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01.

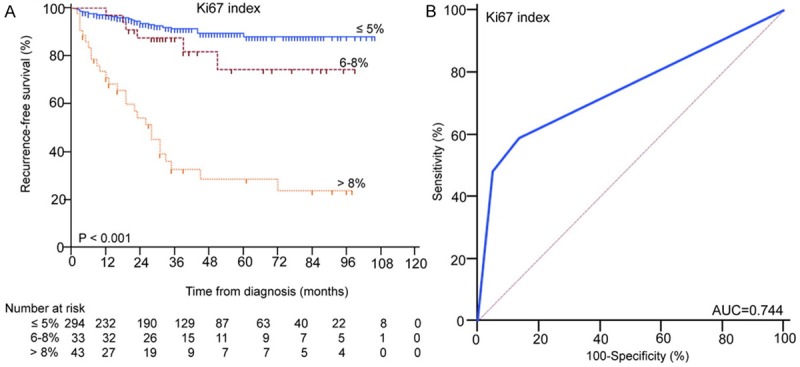

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank test showed GISTs divided by Ki67 index (≤ 5, 6-8 and > 8%) presented different RFS (P < 0.001), as shown in Figure 2A. ROC analysis showed the AUC of Ki67 was 0.744, as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2.

The Kaplan-Meier survival (A) and ROC (B) analysis of Ki67 index in predicting the prognosis of GISTs.

Ki67 index > 8% can effectively sub-divide high-risk GIST patients

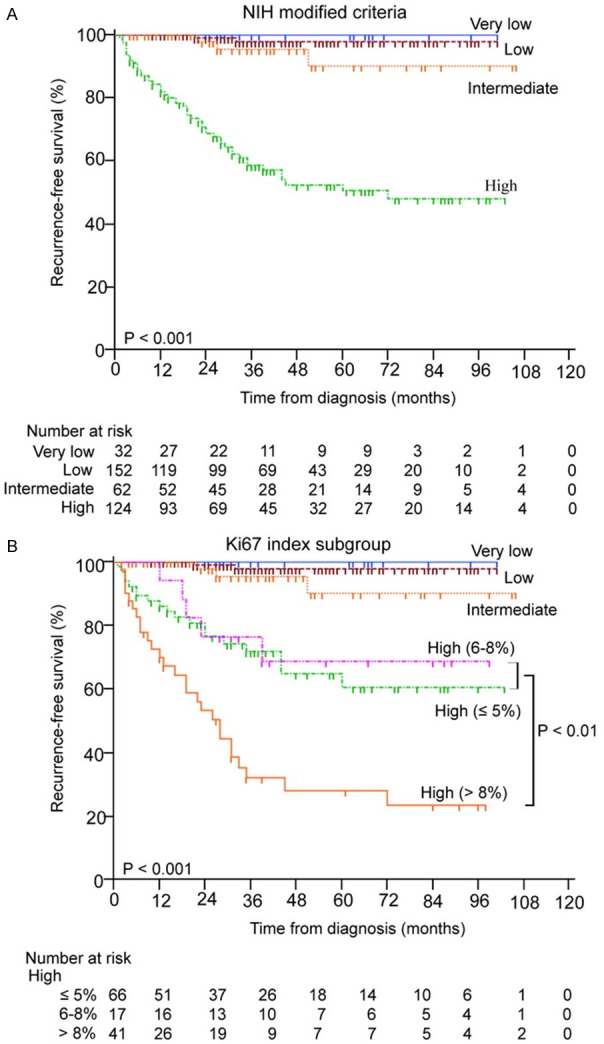

Since Ki67 index was an independently unfavorable prognostic factor for RFS of GIST patients, the further study was focused on whether Ki67 index can sub-divide high-risk GIST patients, which suffered from worse prognosis and higher recurrence rates than very low, low and intermediate-risk patients, classified by NIH modified criteria (Figure 3A). To test our hypothesis, the high-risk GIST patients were divided into 3 groups by Ki67 index (≤ 5, 6-8 and > 8%), Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank test showed Ki67 index > 8% can precisely sub-divide high-risk GISTs effectively, as shown in Figure 3B.

Figure 3.

The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of modified NIH criteria (A) and Ki67 index subgroup (B) in predicting the prognosis of high-risk GISTs.

Ki67 index > 8% may act as a predictive factor for the efficacy of imatinib adjuvant therapy

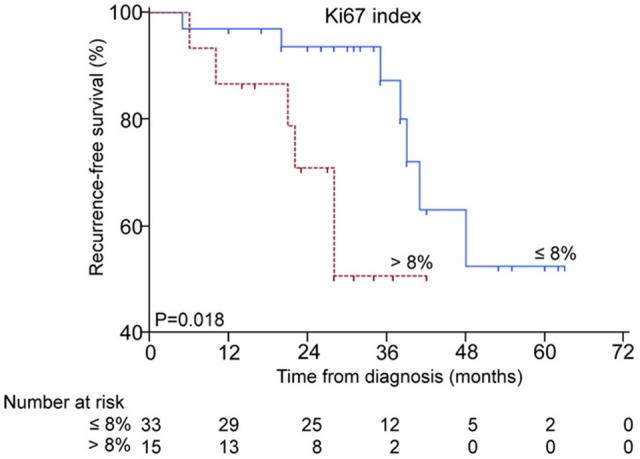

Since high-risk GIST patients after R0 resection indicated adjuvant therapy of imatinib, we further investigated whether Ki67 index > 8% could affect the efficacy of imatinib adjuvant therapy. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank test showed the RFS of patients with Ki67 index > 8% appear a sharply decline of the curve compared with those ≤ 8% (P=0.018) (Figure 4). Multivariate analysis showed Ki67 index > 8% may act as an independently unfavorable factor for imatinib adjuvant therapy (P=0.045) (Table 4).

Figure 4.

The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of Ki67 index in predicting the efficency of imatinib adjuvant therapy.

Table 4.

Multivariate analyses of factors associated with RFS in GIST patients with imatinib adjuvant therapy

| Variable | RFS hazard ratio (95% Cl) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor size (≤ 2, 2-5, 6-10, > 10 cm) | 1.133 (0.531-2.420) | 0.749 |

| Mitosis count (≤ 5, 6-10, > 10/50 HPF) | 1.353 (0.487-3.755) | 0.564 |

| Ki67 index (≤ 8, > 8%) | 3.437 (1.035-11.409) | 0.045* |

P < 0.05.

Discussion

GISTs have a wide various biological behaviors with malignant potential, so it can not be simply distinguished as benign or malignant lesions. Mitotic index, tumor size, tumor site and tumor rupture which are from modified NIH criteria can be important prognostic predictors of GISTs [6,7,18]. According to the NIH guidelines, all GISTs might have malignant potential. Moreover the recurrence risk in high-risk cases was significantly higher than other cases, and even in the same high-risk classification, the clinical outcomes of GIST patients are always variety in our approximate 10 years’ follow-up database. So it is reasonable to assume that there is still some unrevealed room which can be improvement or complementation for current criteria.

Ki67, a commonly accepted nuclear protein associated with cellular proliferation in malignant tumors, had been reported its relationship to the prognosis in GISTs with the sample size from 55 to 94 cases [15-17]. But the criterions for Ki67 index judgment were various in GISTs, some studies use the mean of the index or cutoff level, some refer from criterion in soft tissue sarcoma, which may confuse the clinical reference and application. Our study aims to fully evaluate the prognostic value of Ki67 index in predicting the prognosis of GIST patients and efficiency of imatinib adjuvant therapy based on 418 GIST patients (370 cases only taken the surgery and 48 high-risks taken imatinib adjuvant therapy after R0 resection).

Two cutoff levels were established in our study through statistical analysis, the first was Ki67 > 5% from total Ki67 index (0-30%), the second > 8% was accepted in subdividing relatively “high risk” Ki67 index (6-30%). Finally, we got three groups of Ki67 index in GISTs: Ki67 ≤ 5, 5-8 and > 8%. Through univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with RFS in 370 GIST patients, Ki67 was confirmed as an independent prognostic factors for RFS (P=0.033).

Because the current recurrence-risk criterion of GISTs was established on modified NIH criteria, and high-risk GIST patients suffered much worse prognosis than very low, low or intermediate-risk GISTs. The further study we focused on whether Ki67 index can predict different prognosis in high-risk GISTs, which was more instructive value in clinic. The result showed Ki67 index > 8% can effectively sub-divide high-risk GISTs with different prognosis, which suggested even in the same group of GISTs classified by modified NIH criteria, room still exist for improvement or complementation for more precisely predicting the different outcomes.

With application of imatinib targeted adjuvant therapy in high-risk GISTs, the mortality rate had decreased but recurrence rate remained high [8-10]. We further to investigate whether Ki67 index > 8% could affect efficiency of imatinib adjuvant therapy. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and multivariate analysis showed that GIST patients with Ki67 index > 8% suffered a poorer prognosis, indicated Ki67 index > 8% may act as an unfavorable factor for imatinib adjuvant therapy. Because of the limitation of sample numbers and follow-up time in our study, it still need more works to verified this result, but the high-risk GIST patients with Ki67 index > 8% should be noticed in clinical follow-up because of higher possibility in recurrence even with imatinib adjuvant therapy.

In this study, we analyzed different ki67 index (≤ 5, 5-8 and > 8%) in GIST patients after R0 resection. ki67 index > 8% can improve the modified NIH criteria for distinguishing different outcomes in high-risk GIST patients, and unfavorable effect of imatinib adjuvant therapy. Our study demonstrated Ki67 index is an effective complementation of modified NIH criteria in predicting the prognosis of GISTs.

Acknowledgements

National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81272743); Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology, China (No. 11411950800 and 13XD1402500).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Steigen SE, Eide TJ. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): a review. APMIS. 2009;117:73–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsson B, Bümming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, Odén A, Dortok A, Gustavsson B, Sablinska K, Kindblom LG. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era- a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103:821–829. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mucciarini C, Rossi G, Bertolini F, Valli R, Cirilli C, Rashid I, Marcheselli L, Luppi G, Federico M. Incidence and clinicopathologic features of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. A population-based study. Bmc Cancer. 2007;7:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandvik OM, Søreide K, Kvaløy JT, Gudlaugsson E, Søreide JA. Epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumours: single-institution experience and clinical presentation over three decades. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35:515–520. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pisters PW, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Picus J, Sirulnik A, Stealey E, Trent JC reGISTry Steering Committee. A USA registry of gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients: changes in practice over time and differences between community and academic practices. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2523–2529. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, Miettinen M, O’Leary TJ, Remotti H, Rubin BP, Shmookler B, Sobin LH, Weiss SW. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:459–465. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.123545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joensuu H. Risk stratifi cation of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1411–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joensuu H. Adjuvant therapy for high-risk gastrointestinal stromal tumour: considerations for optimal management. Drugs. 2012;72:1953–1963. doi: 10.2165/11635590-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, Maki RG, Pisters PW, Demetri GD, Blackstein ME, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Brennan MF, Patel S, McCarter MD, Polikoff JA, Tan BR, Owzar K American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Intergroup Adjuvant GIST Study Team. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1097–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60500-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, Hartmann JT, Pink D, Schütte J, Ramadori G, Hohenberger P, Duyster J, Al-Batran SE, Schlemmer M, Bauer S, Wardelmann E, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Nilsson B, Sihto H, Monge OR, Bono P, Kallio R, Vehtari A, Leinonen M, Alvegård T, Reichardt P. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1265–1272. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kontzoglou K, Palla V, Karaolanis G, Karaiskos I, Alexiou I, Pateras I, Konstantoudakis K, Stamatakos M. Correlation between Ki67 and breast cancer prognosis. Oncology. 2013;84:219–225. doi: 10.1159/000346475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pathmanathan N, Balleine RL. Ki67 and proliferation in breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66:512–516. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-201085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koumarianou A, Chatzellis E, Boutzios G, Tsavaris N, Kaltsas G. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of poorly differentiated gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinomas. Endokrynol Pol. 2013;64:60–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rindi G, D’Adda T, Froio E, Fellegara G, Bordi C. Prognostic factors in gastrointestinal endocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2007;18:145–149. doi: 10.1007/s12022-007-0020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Artigiani Neto R, Logullo AF, Stávale JN, Lourenço LG. Ki-67 expression score correlates to survival rate in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) Acta Cir Bras. 2012;27:315–321. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502012000500007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerski MR, Pereira F, Matte US, Oliveira FH, Crusius FL, Waengertner LE, Osvaldt A, Fornari F, Meurer L. Exon 11 mutations, Ki67, and p16(INK4A) as predictors of prognosis in patients with GIST. Pathol Res Pract. 2011;207:701–706. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Vizio D, Demichelis F, Simonetti S, Pettinato G, Terracciano L, Tornillo L, Freeman MR, Insabato L. Skp2 expression is associated with high risk and elevated Ki67 expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimäki J, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, Plank L, Nilsson B, Cirilli C, Braconi C, Bordoni A, Magnusson MK, Linke Z, Sufliarsky J, Federico M, Jonasson JG, Dei Tos AP, Rutkowski P. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:265–274. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]