Abstract

Background

Leguminous plants are able to form a root nodule symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria called rhizobia. This symbiotic association shows a high level of specificity. Beyond the specificity for the legume family, individual legume species/genotypes can only interact with certain restricted group of bacterial species or strains. Specificity in this system is regulated by complex signal exchange between the two symbiotic partners and thus multiple genetic mechanisms could be involved in the recognition process. Knowledge of the molecular mechanisms controlling symbiotic specificity could enable genetic improvement of legume nitrogen fixation, and may also reveal the possible mechanisms that restrict root nodule symbiosis in non-legumes.

Results

We screened a core collection of Medicago truncatula genotypes with several strains of Sinorhizobium meliloti and identified a naturally occurring dominant gene that restricts nodulation by S. meliloti Rm41. We named this gene as Mt-NS1 (for M.truncatulanodulation specificity 1). We have mapped the Mt-NS1 locus within a small genomic region on M. truncatula chromosome 8. The data reported here will facilitate positional cloning of the Mt-NS1 gene.

Conclusions

Evolution of symbiosis specificity involves both rhizobial and host genes. From the bacterial side, specificity determinants include Nod factors, surface polysaccharides, and secreted proteins. However, we know relatively less from the host side. We recently demonstrated that a component of this specificity in soybeans is defined by plant NBS-LRR resistance (R) genes that recognize effector proteins delivered by the type III secretion system (T3SS) of the rhizobial symbionts. However, the lack of a T3SS in many sequenced S. meliloti strains raises the question of how the specificity is regulated in the Medicago-Sinorhizobium system beyond Nod-factor perception. Thus, cloning and characterization of Mt-NS1 will add a new dimension to our knowledge about the genetic control of nodulation specificity in the legume-rhizobial symbiosis.

Keywords: Legume, Medicago truncatula, Nodulation specificity, Nitrogen fixation

Background

Legumes are able to enter into a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria, collectively called rhizobia. The symbiosis culminates in the formation of the root nodule, which provides an optimal environment for the bacteria to fix atmospheric nitrogen for use by the plant. It was estimated that the legume-rhizobial symbiosis can fix more than half of the amount of nitrogen produced by the chemical fertilizer industry [1].

The legume-rhizobial interaction begins with a molecular dialogue between the two symbiotic partners [2]. Flavonoid compounds released into the rhizosphere by the legume roots attract rhizobia and induce the expression of a set of bacterial genes, known as the nod genes [3-5]. The enzymes encoded by the nod genes enable the synthesis and secretion of bacterial lipo-chitooligosaccharides known as nodulation (Nod) factors [2,6]. Perception of Nod factors by the cognate host receptors in turn activates a suite of host responses that are essential for accommodation of bacterial invasion [7-10]. One of the earliest plant responses is the curling of the root hairs which traps rhizobial bacteria within a structure called the colonized curled root hair [11,12]. It is within these trap sites that infection threads are initiated and extended, through which the bacteria are transported and ultimately released to the dividing cortical cells named the nodule primordium [5]. Within these nodule cells, the bacteria are enclosed in host-membrane-bound compartments known as symbiosomes and differentiate into the nitrogen-fixing bacteroids [13,14]. During the last decade, a number of plant genes have been identified in Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus that are required for rhizobial infection and nodule development [15,16]. The cloning and characterization of these genes has revealed the nodulation signaling pathway that is conserved in legumes [17].

A significant property of the legume-rhizobial symbiosis is its high level of specificity [5,18-20]. Beyond the specificity for the legume family, individual legume species/genotypes can only interact with certain restricted group of bacterial species or strains. Specificity in this system can take place at multiple stages of the interaction, ranging from initial bacterial infection and nodulation (nodulation specificity) to late nodule development associated with nitrogen fixation efficiency (nitrogen fixation specificity) [19]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying symbiotic specificity will enable genetic manipulation of the host or bacteria in order to enhance the agronomic potential of the root nodule symbiosis. This can be achieved either by extending the host range of bacterial strains with high nitrogen fixation efficiency or conversely, by excluding indigenous soil strains that are highly competitive for nodulation but with low nitrogen-fixing capability [20].

The establishment of a root nodule symbiosis involves the exchange of a series of signals between the plant and bacteria. Accordingly, genetic control of symbiosis specificity is complex and multiple mechanisms could be involved [19]. It is widely believed that the host range is mainly determined by specific recognition of bacterial Nod factors by the cognate host receptor(s) [5,21-26]. However, natural variation in Nod factor receptors that causes changed specificity has rarely been documented. In contrast, a number of dominant genes have been identified in soybeans and other legumes that restrict nodulation with specific rhizobial strains [20,27-30]. The dominant nature of these genes resembles ‘gene-for-gene’ resistance against plant pathogens [19,20,31]. We have demonstrated that a component of this specificity in soybeans is defined by plant NBS-LRR resistance genes that recognize effector proteins delivered by the type III secretion system (T3SS) of the rhizobial symbionts [20]. However, the lack of a T3SS in many sequenced Sinorhizobium meliloti strains raises the question of how the specificity is regulated in the Medicago-Sinorhizobium system beyond Nod-factor perception. To address this question, we screened a core collection of M. truncatula genotypes with several strains of S. meliloti and identified a naturally occurring dominant gene, Mt-NS1, in M. truncatula that restricts nodulation by S. meliloti Rm41. Genetic mapping experiments indicated that Mt-NS1 is not likely a typical R gene. Thus, cloning and characterization of Mt-NS1 will add a new dimension to our knowledge about the genetic control of nodulation specificity in the legume-rhizobial symbiosis.

Results and discussion

Natural variation in symbiosis specificity in M. truncatula

It had previously been reported that the M. truncatula plants showed differential nitrogen fixation efficiency when inoculated with different rhizobial strains [32-35]. However, to our knowledge, natural variation in nodulation specificity (i.e., Nod + vs. Nod- phenotypes) has not been well-documented. To gain a better understanding of the genetic mechanisms underlying symbiosis specificity in the M. truncatula-Sinorhizobium interaction, we screened a core collection of 31 M. truncatula genotypes using the S. meliloti strains NGR34, NGR247, and Rm41. These plant genotypes capture a wide range of genetic diversity present in natural populations of M. truncatula[36]. This experiment revealed tremendous variation in nodulation capacity and nitrogen fixation specificity between different genotype-rhizobial combinations (Table 1). In particular, this screen revealed that Rm41 was unable to nodulate the plant genotypes F83005.5 and Turkey (Figure 1), while the same plant genotypes nodulated normally with other S. meliloti strains. Thus, we postulate that there exist host genes that control strain-specific nodulation in M. truncatula. For genetic analysis of the nodulation specificity in this system, we chose to focus on F83005.5 because Turkey was not compatible when crossed with several other M. truncatula genotypes.

Table 1.

Natural variation in symbiosis specificity in M. truncatula*

| Plant genotypes |

Rhizobial strains |

Plant genotypes |

Rhizobial strains |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGR247 | NGR34 | Rm41 | NGR247 | NGR34 | Rm41 | ||

| A17 |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

ESP165-D |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

| A20 |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

F11.005-E |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

| Borung |

Fix- |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

F11.013-3 |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

| Caliph-A |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

F20047-A |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

| Cyprus-C |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

F20061-A |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

| DZA055-H |

Fix- |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

F20089-B |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

| DZA105-1 |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

F34.042-D |

Fix- |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

| DZA220 |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

F83005.5 |

Fix- |

Fix- |

Nod- |

| DZA222 |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

GRC020B |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

| DZA233-4 |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

GRC043-1 |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

| DZA315-16 |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

GRC064-B |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

| DZA327-7 |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

Harbinger |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

| DZA045.5 |

Fix- |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

Paraggio |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

| ESP105-L |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Sephi-A |

Fix- |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

| ESP158-A |

Fix- |

Fix+ |

Fix- |

Turkey |

Fix- |

Fix- |

Nod- |

| ESP159-11 | Fix- | Fix+ | Fix- | ||||

*Fix + = pink cylindrical nodules colonized by bacteria able to fix nitrogen; Fix- = small, white and round nodules colonized by bacteria unable to fix nitrogen; Nod- = roots unable to form nodules.

Figure 1.

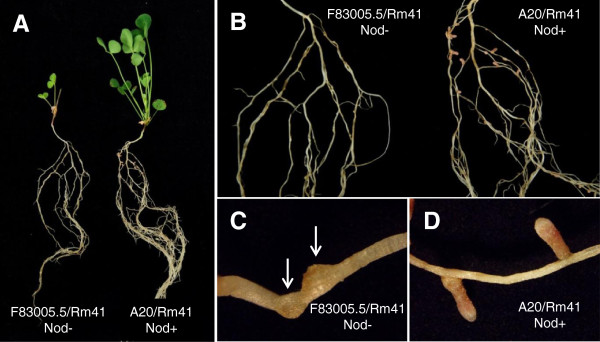

Nodulation and growth phenotypes of M. truncatula plants after inoculation with S. meliloti strain Rm41. A, F83005.5 and A20 lines after inoculation by S. meliloti strain Rm41. A20 (right) grew normally under nitrogen-free conditions, whereas F83005.5 (left) can hardly survive under the same conditions. B, Nodulation phenotypes of the same plants in panel A. A20 roots formed nitrogen-fixing root nodules (right), while F83005.5 cannot nodulate with Rm41. C and D, a closer look at the nodulation phenotypes of A20 and F83005.5, showing fully developed functional nodules on the roots of A20 (D) and the nodule primordial (arrows) formed on the roots of F83005.5 (C).

Rm41 induced root hair curling and nodule primordium formation but failed to infect the roots of F83005.5

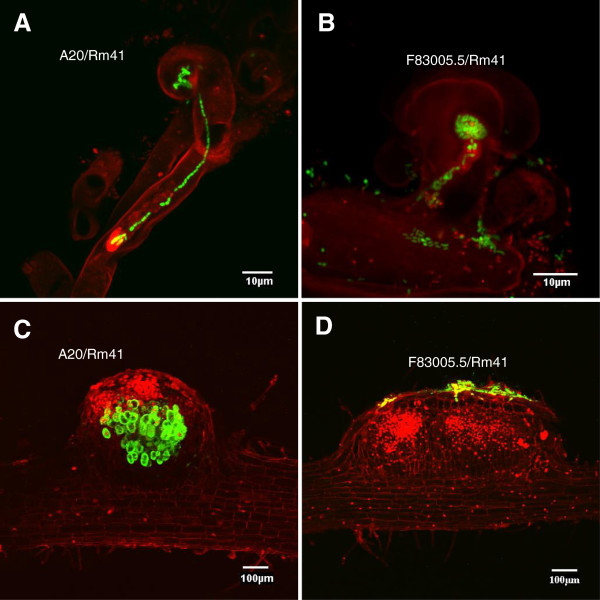

S. meliloti Rm41 is a wild-type strain originally isolated from alfalfa nodules in Hungary [37]. Specifically, this strain contains a strain-specific K antigen (also known as capsular polysaccharides or KPS) which is able to compensate for the lack of exopolysaccharides (EPS) production that is generally required for successful invasion of indeterminate nodules on the alfalfa roots [12,38,39]. The Rm41 genome has recently been sequenced, consisting of a 3.68-Mb chromosome, two symbiotic plasmids (1.56-Mb pSymA and 1.66-Mb pSymB), and a 246-kb nonsymbiotic plasmid pRme41a [40]. It is noteworthy that, similar to many other sequenced S. meliloti strains, the genome of Rm41 does not possess genes encoding a type III secretion system (T3SS) that delivers effector proteins into the host cell [40].To examine the infection process, we used an Rm41 strain that constitutively expresses the green fluorescent protein (GFP) from a stably maintained plasmid vector pHC60. While inoculation of F83005.5 by Rm41 failed to induce root nodule formation, the rhizobial strain was able to induce both root hair curling and nodule primordium formation (Figure 2), suggesting that the early responses of Nod-factor perception were not affected. The bacteria can normally colonize the curled root hairs and occasionally, we can detect aborted, aberrant infection threads present on the F83005.5 roots (Figure 2B). However, in contrast to the compatible interaction between Rm41 and A20 (Figure 2A), normal infection threads were never observed on the roots of F83005.5. In consistent with these observations, the nodule primordia on the F83005.5 roots contained no bacteria despite frequent presence of bacterial colonies on the epidermal surface of the nodule primordia (Figure 2D). Due to a lack of infection, cortical cell division on the F83005.5 roots ceased at an early stage, whereas on A20 roots, infected nodule primordia were readily formed within 4–5 days post inoculation (Figure 2C). Based on these observations, we conclude that the restriction of nodulation by Rm41 in F83005.5 was due to block of bacterial infection rather than a failure in Nod factor perception.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence microscopy analyses of infection process of compatible and incompatible interactions between M. truncatula plants and Rm41. All images are composite images of GFP-expressing Rm41 cells (green) and root cells (red). A, Typical infection thread formed by compatible interaction between A20 and Rm41. The infection thread extends from the colonized, curled root hair to the base of the root hair cell. B, In the incompatible interaction between F83005.5 and Rm41, the bacteria can normally colonize the curled root hairs but typical infection threads cannot be detected. Occasionally, we can detect aborted, aberrant infection threads present on the F83005.5 roots. C, The nodule primordium on the A20 roots contained bacteria, while the nodule primordia on the F83005.5 roots (D) contained no bacteria despite frequent presence of bacterial colonies on the epidermal surface of the nodule primordia.

Exopolysaccharides production of Rm41 is required for establishing efficient symbiotic interactions with M. truncatula

Rhizobial surface polysaccharides, such as exopolysaccharides (EPS), capsular polysaccharides (KPS), and lipopolysaccharides (LPS), form complex macromolecular structures at the bacterium–plant interface and play important roles in establishment of the symbiotic relationship between the host and bacteria [12,19,38,41,42]. In particular, these polysaccharides have been implicated in playing a key role in facilitating infection thread initiation and extension in the alfalfa-S. meliloti interactions [38,43,44]. Despite being symbiotically important, these molecules, as common microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) of the rhizobial bacteria, may also trigger defense responses upon recognition by the cognate host pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and thus are possibly associated with symbiosis specificity.

We inoculated the A20 (Nod+), DZA045.5 (Nod+), and F83005.5 (Nod-) plants with Rm41 mutants that are defective in production of various components of surface polysaccharides. The mutants used in this study included AK631, an exoB mutant of Rm41 deficient in EPS production (EPS-); PP4709, an rkp1 mutant of RM41 deficient in production of KPS (KPS-), and PP674, an rkp1 mutant of AK631 deficient in production of both EPS and KPS (EPS-KPS-) (Table 2). Our data showed that PP4709 (KPS-) behaved similar to the wild-type strain Rm41 and can normally nodulate A20 and DZA045.5, suggesting that KPS production of Rm41 is not required for nodulation with the M. truncatula genotypes A20 and DZA045.5. In contrast, AK631 (ESP-) and PP674 (EPS-KPS-) were not able to nodulate DZA045.5, and AK631 only induced the formation of a few Fix- nodules on the A20 roots, which suggested that EPS production plays an important role in establishing an efficient symbiosis with M. truncatula and their role can’t be complemented by KPS. Our data are consistent with that reported by Simesk et al. [35].

Table 2.

Nodulation phenotypes of M. truncatula genotypes with Rm41 mutants

| F83005.5 | DZA045.5 | A20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rm41 |

Nod- |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

| AK631 (EPS-) |

Nod- |

Nod- |

Fix-* |

| PP4709 (KPS-) |

Nod- |

Fix+ |

Fix+ |

| PP674 (EPS-KPS-) | Nod- | Nod- | Nod- |

*Only a few non functional nodules were formed.

Neither single nor double mutants of Rm41 could nodulate F83005.5, which appears to suggest that the incompatibility between F83005.5 and Rm41 is not associated with EPS and KPS production. However, we can’t exclude the possibility that EPS is required for nodulation in the compatible interaction but also essential for eliciting defense responses in the F83005.5 background. This scenario is similar to the T3SS of pathogenic bacteria, for which T3SS is required for causing disease in susceptible hosts and for eliciting the hypersensitive response in resistant hosts, and defects in the T3SS renders a bacterium non-pathogenic [45].

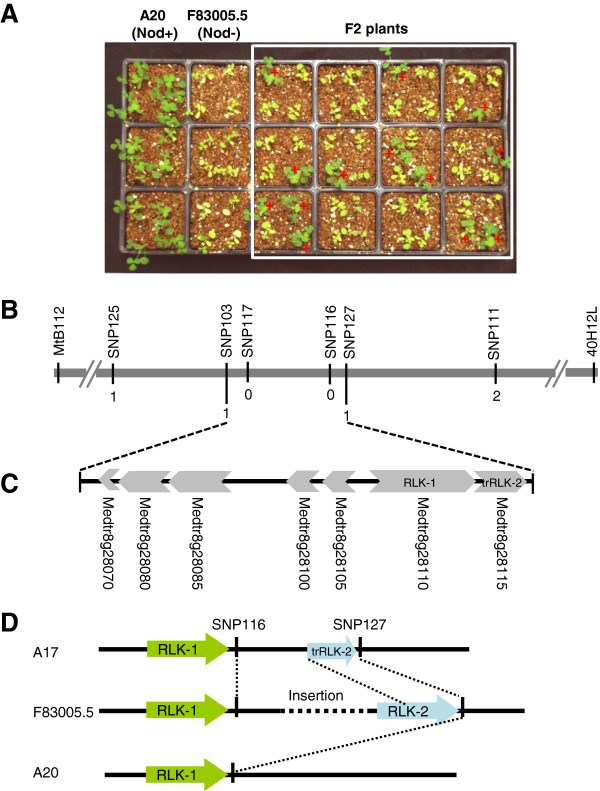

The restriction of nodulation by Rm41 in F83005.5 is controlled by a single dominant gene

For genetic analysis of the nodulation specificity, we used an F2 population derived from the cross between the two M. truncatula genotypes A20 and F83005.5. A20 showed Nod + Fix + phenotype when inoculated with Rm41. From a total of 2,623 inoculated F2 plants, 686 plants nodulated, which fits the 3:1 (non-nodulation to nodulation) ratio (χ2 = 1.86, df = 1, P = 0.17; Figure 3A), suggesting that the restriction of nodulation by Rm41 in F83005.5 is controlled by a single dominant gene. We named this gene as Mt-NS1 (for M. truncatula nodulation specificity 1). Consistent with the cytological studies described above, the dominant nature of this gene indicates that the non-nodulation phenotype of F83005.5 is not due to a failure in Nod factor perception but resembles ‘gene-for-gene’ resistance against pathogen infections.

Figure 3.

Genetic mapping of Mt-NS1. A, Growth phenotypes of A20 (Nod+, ns1/ns1), F83005.5 (Nod-, NS1/NS1), and a subpopulation of F2 plants three weeks post inoculation with S. meliloti Rm41. Nodulated plants are green and healthy, whereas the non-nodulated plants showed nitrogen starvation symptoms with yellowish leaves under the nitrogen-free condition. B, Fine mapping of Mt-NS1. The Mt-NS1 locus was delimited to a genomic region between markers SNP103 and SNP127. Numbers indicate the number of recombination breakpoints separating the marker from Mt-NS1 based on genotyping ~3,900 F2 plants. C, Annotation of the 50-kb genomic DNA of Jemalong A17 (Nod + Fix-, ns1/ns1) that covers the candidate gene region identifies 7 putative genes (Medtr8g28070-Metr8g28115). D, Identification of an insertion/deletion polymorphism between the two copies of the receptor-like kinases (Metr8g28110 and Metr8g28115) among the genomes of Jemalong A17, A20, and F83005.5.

Genetic mapping of Mt-NS1

Genetic mapping of Mt-NS1 was initially carried out in an F2 population derived from the cross between A20 and F83005.5, which allowed us to map the Mt-NS1 locus on chromosome 8, defined by the flanking markers MtB112 and 40H12L (Figure 3B). However, the extremely low levels of sequence polymorphisms between A20 and F83005.5 prevented us from using this population for fine mapping of the locus. To solve this problem, we developed another F2 population derived from the cross of DZA045.5 (Nod + Fix+) and F83005.5.

We took advantage of the availability of the M. truncatula genome sequence [46] to develop high-density SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) markers for fine mapping of the Mt-NS1 locus. SNPs were genotyped either by converting to CAPS (cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences) markers or by direct sequencing. Phenotyping and genotyping a total of 3,900 F2 plants using the SNP markers allowed us to delimit the Mt-NS1 locus between SNP103 and SNP127 (Figure 3B), which span ~50 kb based on the genome sequence of Jemalong A17 (Nod + Fix-). The 50-kb genomic sequence of Jemalong A17 contains at least six predicted genes based on the Medicago truncatula genome release version 4.0 (http://www.jcvi.org/medicago) (Figure 3C). These genes include Medtr8g028070, a ferric-chelate reductase-like protein; Medtr8g028080, an RNase T2 family protein; Medtr8g028085 and Medtr8g028100, two highly conserved proteins with unknown function; Medtr8g028105, an A/G-specific adenine DNA glycosylase-like protein; and Medtr8g028110, a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (LRR-RLK). In particular, the LRR-RLK (Medtr8g028110; here we call it as RLK-1) is structurally similar to the DMI2/SYMRK orthologs in legumes that are required for both rhizobial and mycorrhizal symbioses, which consists of an N-terminal signal peptide, an extracellular malectin-like domain comprising three leucine-rich repeats, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular protein kinase domain [47,48]. In addition, there exists a tandem duplication–truncation of the RLK-1 gene (annotated as Medtr8g028115; here we call it as trRLK-2) (Figure 3C). As described below, the presence of a large insertion/deletion polymorphism around the Mt-NS1 locus between F83005.5 and Jemalong A17 complicated the prediction of candidate genes.

Identification of an insertion/deletion polymorphism around the Mt-NS1 locus

Based on our knowledge of the signaling pathways in pathogenic and symbiotic plant-microbe interactions, we had assumed that RLK-1 was a strong candidate gene for Mt-NS1. This gene may serve as a receptor that directly or indirectly perceives a yet unknown bacterial signal, which in turn triggers host defense responses and blocks bacterial infection. Support of this hypothesis also came from the fact that this gene showed root-specific expression (data not shown). However, we did not detect any expression- and sequence-level polymorphisms between the F83005.5 and A20 alleles of RLK-1. Since the phenotype of the reference genotype A17 is Nod + Fix- (ns1/ns1), it is possible that ns1 represents a null allele in A17. Full cDNA amplification identified two copies of LRR-RLK genes in F83005.5; one corresponds to RLK-1 and another matches to the truncated copy trRLK-2 in A17. This indicated that trRLK-2 is truncated in A17 but not in F83005.5 (Figure 3D). We also found that the RLK-2 is missing in the A20 genome. Further genome sequencing between the two tandem copies revealed an insertion/deletion polymorphism between the three genomes (Figure 3D). The exact size of the insertion in F83005.5 is currently unknown. We are in the process of testing the candidate genes including RLK-2, but our initial experiments showed that transgenic alfalfa and M. truncatula roots containing RLK-2 failed to restrict nodulation by Rm41. Thus, it is likely that NS1 resides in the insertion of F83005.5 and the identity is unknown. The insertion size could be very large because our long-range PCR experiments were unsuccessful to fill the gap. Further de-novo resembling of sequences from other genotypes is required to resolve this issue.

Conclusions

Establishing a successful interaction between legumes and rhizobia requires signal recognition between the two symbiotic partners. Thus, the evolution of symbiosis specificity involves both rhizobial and host genes. From the bacterial side, specificity determinants include Nod factors, surface polysaccharides, and secreted proteins. However, we know relatively less from the host side. Perception of the Nod-factor signal is mediated by direct binding to the host Nod factor receptors (NFRs), which are plasma membrane-localized receptor kinases containing LysM motifs in their extracellular domains [49]. The role of NFRs in regulating host specificity was demonstrated by transferring the L. japonicus versions of NFRs to M. truncatula, which enabled the transgenic M. truncatula roots to nodulate with the L. japonicus symbiont Mesorhizobium loti[24]. However, natural variation in NFRs that causes changed specificity has rarely been documented. In contrast, numerous dominant genes have been identified in soybeans and other legumes that restrict nodulation with specific rhizobial strains [20,30]. We recently cloned the two soybean genes Rj2 and Rfg1 that restrict nodulation with specific strains of Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Sinorhizobium fredii, respectively [20]. We demonstrated that Rj2 and Rfg1 are allelic genes encoding a member of the Toll-interleukin receptor/nucleotide-binding site/leucine-rich repeat (TIR-NBS-LRR) class of plant resistance (R) proteins. Our discovery is consistent with recent reports that documented a large number of secreted effectors delivered into the host cell by rhizobial T3SS and suggests that establishment of a root nodule symbiosis requires the evasion of plant immune responses triggered by rhizobial effectors.

In this study, we have identified a naturally occurring dominant gene, Mt-NS1, in M. truncatula that prevents nodulation with S. meliloti Rm41 and made significant progress toward cloning the gene. The lack of T3SS-encoding genes in the Rm41 genome suggests that Mt-NS1 unlikely encode an R gene. Consistent with prediction, we did not identify typical R gene homologs around the Mt-NS1 locus. We hypothesize that Mt-NS1 likely encodes a pattern recognition receptor that mediates specific recognition of yet unknown MAMPs of the rhizobial bacteria, resulting in host defense responses. Thus, cloning and characterization of Mt-NS1 will provide novel insights into the genetic control of nodulation specificity in the legume-rhizobial symbiosis.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth media

The rhizobial strains used in this study included wild-type S. meliloti strains NGR34 [50], NGR247 [50], and Rm41 [37] plus several mutant strains of Rm41: AK631 (exoB631, ESP-), PP674 (exoB631/rpkA::Tn5, EPS-KPS-), and PP4409 (rpk1::Tn5, KPS-) [51,52]. The Rm41 strain used for fluorescence microscopy contained pHC60 [42], a stably maintained plasmid that constitutively expresses GFP. Strains were grown in TY agar medium at 28°C [53]. Antibiotics were used at 50 μg/ml for spectinomycin and 200 μg/ml for neomycin.

Plant growth and nodulation assay

M. truncatula genotypes used in this study were listed in Table 1. Two F2 populations were developed for genetic mapping of Mt-NS1; one was derived from the cross between A20 and F83005.5 and another from the cross of DZA045.5 x F83005.5. Seedlings of parents and the segregating populations were grown in a 50–50 mixture of vermiculite and Turface in a growth chamber programmed for 16 h light at 22°C and 8 h dark at 20°C. The plants were grown under nitrogen-free conditions. For nodulation assay, roots of one-week-old seedlings were inoculated with rhizobial bacteria; each plant was flood-inoculated with 1 ml of a cell suspension with an optical density at 600 nm of 0.1. Nodulation phenotypes were recorded three weeks post inoculation.

Genetic mapping

For genetic mapping, we first used SSR (simple sequence repeat) markers with known genetic position to localize the approximate position of Mt-NS1. Additional markers were then developed based on genomic sequence surrounding the Mt-NS1 locus. Markers were based on SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) identified between the two parents. For this purpose, primers were designed for PCR amplification of genomic DNA from the two parents of the F2 mapping population, followed by sequencing the PCR products to identify sequence polymorphisms. Where possible, SNPs were converted to CAPS (cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences) markers for genotyping; otherwise, they were genotyped by direct sequencing.

Fluorescence microscopy

For fluorescence microscopy, roots inoculated with GFP-expressing Rm41 were examined for infection thread formation 5–7 days post inoculation using a FV1000 point-scanning/point-detection laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus). Before microscopic analysis, the roots were counterstained with 10 mg/ml propidium iodide for 1 minute. After staining, roots were quickly dipped in distilled water to rinse, and mounted under a coverslip. The fluorescence excitation is 488 nm for GFP, and 535 nm for propidium iodide; GFP emission was captured and collected at 520 ± 15 through GFP filter; propidium iodide emission was detected in another channel using a 520 ± 15 nm bandpass. Image acquisition was performed at a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels and a scan rate of 20 μs pixel-1. The FLUOVIEW 1.5 software (Olympus) was used to control the microscope and export images. To examine the bacterial colonization in cortical cells, the nodules or nodule primordia were sliced longitudinally to 100-300 μm thickness before microscopic analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HZ conceived the project. JL, SY, and QZ carried out the experiments. HZ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jinge Liu, Email: jinge.liu@uky.edu.

Shengming Yang, Email: syang2@uky.edu.

Qiaolin Zheng, Email: qiaolinzheng@uky.edu.

Hongyan Zhu, Email: hzhu4@uky.edu.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Bradley L. Reuhs (Purdue University), Kathryn M. Jones (Florida State University), and Peter Putnoky (University of Pecs, Hungary) for providing the S. meliloti strains used in this study. We also thank Dr. Jean-Marie Prosperi (INRA, France) for providing M. truncatula seeds. This research was supported by a grant from Kentucky Science and Engineering Foundation and a grant from United States Department of Agriculture-Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (to HZ).

References

- Fowler D, Coyle M, Skiba U, Sutton MA, Cape JN, Reis S, Sheppard LJ, Jenkins A, Grizzetti B, Galloway JN, Vitousek P, Leach A, Bouwman AF, Butterbach-Bahl K, Dentener F, Stevenson D, Amann M, Voss M. The global nitrogen cycle in the twenty-first century. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20130164. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RF, Long SR. Rhizobium–plant signal exchange. Nature. 1992;357:655–660. doi: 10.1038/357655a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SR. Rhizobium symbiosis: nod factors in perspective. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1885–1898. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck MC, Fisher RF, Long SR. Diverse flavonoids stimulate NodD1 binding to nod gene promoters in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5417–5427. doi: 10.1128/JB.00376-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perret X, Staehelin C, Broughton WJ. Molecular basis of symbiotic promiscuity. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:180–201. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.1.180-201.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerouge P, Roche P, Faucher C, Maillet F, Truchet G, Promé JC, Dénarié J. Symbiotic host-specificity of Rhizobium meliloti is determined by a sulphated and acylated glucosamine oligosaccharide signal. Nature. 1990;344:781–784. doi: 10.1038/344781a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amor BB, Shaw SL, Oldroyd GE, Maillet F, Penmetsa RV, Cook D, Long SR, Dénarié J, Gough C. The NFP locus of Medicago truncatula controls an early step of Nod factor signal transduction upstream of a rapid calcium flux and root hair deformation. Plant J. 2003;34:495–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limpens E, Franken C, Smit P, Willemse J, Bisseling T, Geurts R. LysM domain receptor kinases regulating rhizobial Nod factor-induced infection. Science. 2003;302:630–633. doi: 10.1126/science.1090074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen EB, Madsen LH, Radutoiu S, Olbryt M, Rakwalska M, Szczyglowski K, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J. A receptor kinase gene of the LysM type is involved in legume perception of rhizobial signals. Nature. 2003;425:637–640. doi: 10.1038/nature02045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Madsen EB, Felle HH, Umehara Y, Gronlund M, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J. Plant recognition of symbiotic bacteria requires two LysM receptor-like kinases. Nature. 2003;425:585–592. doi: 10.1038/nature02039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esseling JJ, Lhuissier FG, Emons AM. Nod factor-induced root hair curling: continuous polar growth towards the point of nod factor application. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1982–1988. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KM, Kobayashi H, Davies BW, Taga ME, Walker GC. How rhizobial symbionts invade plants: the Sinorhizobium-Medicago model. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:619–633. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin NJ. Plant cell wall remodelling in the Rhizobium–Legume symbiosis. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2004;23:293–316. doi: 10.1080/07352680490480734. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limpens E, Mirabella R, Fedorova E, Franken C, Franssen H, Bisseling T, Geurts R. Formation of organelle-like N2-fixing symbiosomes in legume root nodules is controlled by DMI2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10375–10380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504284102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd GE, Harrison MJ, Paszkowski U. Reprogramming plant cells for endosymbiosis. Science. 2009;324:753–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1171644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen LH, Tirichine L, Jurkiewicz A, Sullivan JT, Heckmann AB, Bek AS, Ronson CW, James EK, Stougaard J. The molecular network governing nodule organogenesis and infection in the model legume Lotus japonicus. Nat Commun. 2010;1:1–12. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd GE. Speak, friend, and enter: signalling systems that promote beneficial symbiotic associations in plants. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:252–263. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton WJ, Jabbouri S, Perret X. Keys to symbiotic harmony. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5641–5652. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.20.5641-5652.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Yang S, Tang F, Zhu H. Symbiosis specificity in the legume-rhizobial mutualism. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:334–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Tang F, Gao M, Krishnan HB, Zhu H. R gene-controlled host specificity in the legume-rhizobia symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18735–18740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011957107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Henderson WR, Djordjevic MA. A cultivar-specific interaction between Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii and subterranean clover is controlled by nodM, other bacterial cultivar specificity genes, and a single recessive host gene. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2791–2799. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2791-2799.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts R, Heidstra R, Hadri AE, Downie JA, Franssen H, Van Kammen A, Bisseling T. Sym2 of pea is involved in a nodulation factor-perception mechanism that controls the infection process in the epidermis. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:351–359. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.2.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaink HP, Sheeley DM, van Brussel AA, Glushka J, York WS, Tak T, Geiger O, Kennedy EP, Reinhold VN, Lugtenberg BJ. A novel highly unsaturated fatty acid moiety of lipo-oligosaccharide signals determines host specificity of Rhizobium. Nature. 1992;354:125–130. doi: 10.1038/354125a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche P, Debellé F, Maillet F, Lerouge P, Faucher C, Truchet G, Dénarié J, Promé JC. Molecular basis of symbiotic host specificity in Rhizobium meliloti: nodH and nodPQ genes encode the sulfation of lipo-oligosaccharide signals. Cell. 1991;67:1131–1143. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90290-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd GE, Downie JA. Calcium, kinases and nodulation signalling in legumes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:566–576. doi: 10.1038/nrm1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Madsen EB, Jurkiewicz A, Fukai E, Quistgaard EM, Albrektsen AS, James EK, Thirup S, Stougaard J. LysM domains mediate lipochitin-oligosaccharide recognition and Nfr genes extend the symbiotic host range. EMBO J. 2007;26:3923–3935. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell BE. Inheritance of a strain specific ineffective nodulation in soybeans. Crop Sci. 1966;6:427–428. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1966.0011183X000600050010x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vest G, Caldwell BE. Rj4: A gene conditioning ineffective nodulation in soybean. Crop Sci. 1972;12:692. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1972.0011183X001200050042x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trese AT. A single dominant gene in McCall soybean prevents effective nodulation with Rhizobium fredii USDA257. Euphytica. 1995;81:279–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00025618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MA. Mutualism in metapopulations of legumes and rhizobia. Am Nat. 1999;153:S48–S60. doi: 10.1086/303211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowsky MJ, Cregan PB, Rodriguez-Quinones F, Keyser HH. Microbial influence on gene-for-gene interactions in legume-Rhizobium symbioses. Plant Soil. 1990;129:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00011691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyman CP, Strijdom BW. Symbiotic characteristics of lines and cultivars of Medicago truncatula inoculated with strains of Rhizobium meliloti. Phytophylatica. 1980;12:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Tirichine L, de Billy F, Huguet T. Mtsym6, a gene conditioning Sinorhizobium strain-specific nitrogen fixation in Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:845–851. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.3.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Colmenares A, Kahn ML. Determination of nitrogen fixation effectiveness in selected Medicago truncatula isolates by measuring nitrogen isotope incorporation into pheophytin. Plant Soil. 2005;270:159–168. doi: 10.1007/s11104-004-1308-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simsek S, Ojanen-Reuhs T, Stephens SB, Reuhs BL. Strain-ecotype specificity in Sinorhizobium meliloti-Medicago truncatula symbiosis is correlated to succinoglycan oligosaccharide structure. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:7733–7740. doi: 10.1128/JB.00739-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Geddes J, Paape T, Epstein B, Briskine R, Yoder J, Mudge J, Bharti AK, Farmer AD, Zhou P, Denny R, May GD, Erlandson S, Yakub M, Sugawara M, Sadowsky MJ, Young ND, Tiffin P. Candidate genes and genetic architecture of symbiotic and agronomic traits revealed by whole-genome, sequence-based association genetics in Medicago truncatula. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondorosi A, Kiss GB, Forrai T, Vincze E, Banfalvi Z. Circular linkage map of Rhizobium meliloti chromosome. Nature. 1977;268:525–527. doi: 10.1038/268525a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pellock BJ, Cheng HP, Walker GC. Alfalfa root nodule invasion efficiency is dependent on Sinorhizobium meliloti polysaccharides. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4310–4318. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.15.4310-4318.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pálvölgyi A, Deák V, Poinsot V, Nagy T, Nagy E, Kerepesi I, Putnoky P. Genetic analysis of the rkp-3 gene region in Sinorhizobium meliloti 41: rkpY directs capsular polysaccharide synthesis to KR5 antigen production. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22:1422–1430. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-11-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidner S, Baumgarth B, Göttfert M, Jaenicke S, Pühler A, Schneiker-Bekel S, Serrania J, Szczepanowski R, Becker A. Genome sequence of Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm41. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00013–12. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00013-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deakin WJ, Broughton WJ. Symbiotic use of pathogenic strategies: Rhizobial protein secretion systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:312–320. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis R, Van Gijsegem F, De Rycke R, D’Haeze W, Van Maelsaeke E, Anthonio E, Van Montagu M, Holsters M, Vereecke D. Lipopolysaccharides as a communication signal for progression of legume endosymbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2655–2660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409816102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J, Walker GC. A novel exopolysaccharide can function in place of the calcofluor-binding exopolysaccharide in nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. Cell. 1989;56:661–672. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90588-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HP, Walker GC. Succinoglycan is required for initiation and elongation of infection threads during nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5183–5191. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5183-5191.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner D, He SY. Type III protein secretion in plant pathogenic bacteria. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1656–1664. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.139089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ND, Debellé F, Oldroyd GE, Geurts R, Cannon SB, Udvardi MK, Benedito VA, Mayer KF, Gouzy J, Schoof H, Van de Peer Y, Proost S, Cook DR, Meyers BC, Spannagl M, Cheung F, De Mita S, Krishnakumar V, Gundlach H, Zhou S, Mudge J, Bharti AK, Murray JD, Naoumkina MA, Rosen B, Silverstein KA, Tang H, Rombauts S, Zhao PX, Zhou P. et al. The Medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature. 2011;480:520–524. doi: 10.1038/nature10625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endre G, Kereszt A, Kevei Z, Mihacea S, Kalo P, Kiss GB. A receptor kinase gene regulating symbiotic nodule development. Nature. 2002;417:962–966. doi: 10.1038/nature00842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke S, Kistner C, Yoshida S, Mulder L, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J, Szczyglowski K, Parniske M. A plant receptor-like kinase required for both bacterial and fungal symbiosis. Nature. 2002;417:959–962. doi: 10.1038/nature00841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broghammer A, Krusell L, Blaise M, Sauer J, Sullivan JT, Maolanon N, Vinther M, Lorentzen A, Madsen EB, Jensen KJ, Roepstorff P, Thirup S, Ronson CW, Thygesen MB, Stougaard J. Legume receptors perceive the rhizobial lipochitin oligosaccharide signal molecules by direct binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13859–13864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205171109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen P, Wright S, Collins M, Rice W. Patterns of reactivity between a panel of monoclonal antibodies and forage Rhizobium strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:654–661. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.654-661.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovics G, Putnoky P, Reuhs BL, Kim JS, Thorp TA, Noel D, Carlson RW, Kondorosi A. The presence of a novel type of surface polysaccharide in Rhizobium meliloti requires a new fatty acid synthase-like gene cluster involved in symbiotic nodule development. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1093–1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnoky P, Petrovics G, Kereszt A, Grosskopf E, Ha DTC, Banfalvi Z, Kondorosi A. Rhizobium meliloti lipopolysaccharide and exopolysaccharide can have the same function in the plant-bacterium interaction. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5450–5458. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5450-5458.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beringer JE. R-factor transfer in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Gen Microbiol. 1974;84:188–198. doi: 10.1099/00221287-84-1-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]