Abstract

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy is emerging as a powerful approach to determine structure, topology, and conformational dynamics of membrane proteins at the atomic level. Conformational dynamics are often inferred and quantified from the motional averaging of the NMR parameters. However, the nature of these motions is difficult to envision based only on spectroscopic data. Here, we utilized restrained molecular dynamics simulations to probe the structural dynamics, topology and conformational transitions of regulatory membrane proteins of the calcium ATPase SERCA, namely sarcolipin and phospholamban, in explicit lipid bilayers. Specifically, we employed oriented solid-state NMR data, such as dipolar couplings and chemical shift anisotropy measured in lipid bicelles, to refine the conformational ensemble of these proteins in lipid membranes. The samplings accurately reproduced the orientations of transmembrane helices and showed a significant degree of convergence with all of the NMR parameters. Unlike the unrestrained simulations, the resulting sarcolipin structures are in agreement with distances and angles for hydrogen bonds in ideal helices. In the case of phospholamban, the restrained ensemble sampled the conformational interconversion between T (helical) and R (unfolded) states for the cytoplasmic region that could not be observed using standard structural refinements with the same experimental data set. This study underscores the importance of implementing NMR data in molecular dynamics protocols to better describe the conformational landscapes of membrane proteins embedded in realistic lipid membranes.

Introduction

Almost all biomembranes are in a liquid-crystalline lamellar state (Lα phase), where phospholipid dynamics maintain liquid-like properties of the lipid bilayers (1). Integral membrane proteins have structural and chemical features matching the anisotropic nature of the lipid membranes in which they are embedded. Within the lipid matrix, membrane proteins undergo complex conformational dynamics, such as rotational diffusion about the membrane normal, pitching about the tilt angle (θ), and lateral diffusion, as well as internal motions such as librations of the peptide planes, fluctuations of loops, and large-scale conformational transitions. These dynamics can cover different timescales (i.e., from subnanoseconds to milliseconds and beyond) and have key functional roles.

In past decades, solid-state NMR (ssNMR) techniques have emerged as powerful approaches for the characterization of membrane protein conformational dynamics at the atomic level. ssNMR techniques are especially tailored to probe both global and internal motions (2,3). Unlike x-ray crystallography, ssNMR samples are prepared using lipid membranes, with lipid/protein ratios that closely mimic those in natural membrane environments (4,5). Using these preparations, structural and dynamic NMR parameters can be obtained by either oriented ssNMR or magic-angle-spinning (MAS) NMR spectroscopy (5–7). These two approaches are highly complementary and can be used in tandem to obtain both structure and topology of membrane proteins (8–11). The MAS techniques are used to measure isotropic chemical shifts, which give information on torsion angles, as well as distances (12–14). In addition, recoupling experiments enable the recovery of anisotropic dipolar and chemical shift parameters that can be used to orient chemical groups with respect to an internal reference axis (15–17). In contrast, oriented ssNMR enables the direct detection of dipolar couplings (DCs) and chemical shift anisotropy (CSA), but it requires samples that are uniformly aligned with respect to an external reference frame (18,19). Both MAS and oriented ssNMR techniques carry intrinsic information on the dynamics of membrane proteins (3); however, their interpretation in terms of conformational dynamics (internal protein motions) is still a matter of debate.

To address this issue, theoretical approaches have been extensively applied and several different models have been proposed to describe the dynamics of membrane proteins (20,21). However, their general applicability is questionable, as the systems studied and reported in the literature are still quite sparse. Atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which in the past few years have undergone significant progress, represent a promising approach to study these systems (22–27). Nonetheless, the imperfections in the parameterizations of the force fields, as well as the difficulties in sampling the large conformational phase space of the membrane/protein/water systems, still represent significant challenges for MD calculations of membrane proteins. Although experimental and theoretical approaches may be affected individually by inherent limitations, a general view is emerging in which the combination of sparse experimental data and molecular simulations can be used to provide a significant step forward in the characterization of protein structure and dynamics (28–33), including those highly dynamical membrane protein states that exert their biological functions through order-disorder transitions or transient protein-protein interactions at the membrane surface.

In this article, we exploit the combination of ssNMR and first-principles MD simulations to describe the conformational dynamics and topology of the 31-residue membrane protein sarcolipin (SLN) and the 53-residue membrane protein phospholamban (PLN) in 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) lipid bilayers. Both SLN and PLN have been extensively characterized by solution (34,35) and ssNMR spectroscopy (8,10,36–38), and the two proteins play a crucial role in cardiac muscle contractility, regulating (SERCA), a P-type ATPase that is responsible for the active transport of Ca2+ ions into the sarcoplasmic reticulum (39–44).

We employed oriented ssNMR data such as 1H-15N DC and 15N CSA as restraints in the MD calculations. CSA and DC measured by oriented ssNMR spectroscopy in oriented lipid bicelles are powerful structural restraints for MD (45,46) and structural refinement (3,47–49), as they provide direct information on the orientations of bond vectors and peptide planes with respect to the lipid bilayer. These data constitute sensitive probes of tilt (θ) and azimuthal (ρ, rotational) angles of transmembrane (TM) helices (4,5). Moreover, these restraints, being sensitive to changes in orientation with respect to the external magnetic field, are ideal for understanding site-specific as well as whole-body dynamics.

Our restrained simulations generated highly accurate structural ensembles that showed significantly improved topological, dynamical, and structural properties in very good agreement with the experimental data. Not only do the restrained simulations rectify the helical tilt and azimuthal angles compared to the unrestrained simulations; they also improve the agreement with fast motions as probed by 15N relaxation S2 in SLN (34). In addition, the resulting structures do not show the prominent curvature observed in the unrestrained simulations; rather, the SLN helix is more regular, displaying hydrogen-bond distances and angles typical of ideal helices. Finally, the employment of ensemble-averaged restrained MD simulations provides a description of the conformational equilibria of the cytosplasmic region of PLN, showing the interconversion between the T and R states, which is an essential component of its mechanism of SERCA regulation (50). These encouraging results support the view that membrane protein simulations integrating oriented ssNMR data can be quite accurate in describing biomolecular processes and interactions at the cellular membrane.

Methods

CSA and DC restrained MD

To generate the structural ensemble of membrane proteins, we first implemented CSA and DC restraints in the GROMACS package for MD simulations (51), which allows the use of a variety of force fields for proteins, water molecules, and lipids, as well as a large number of integration methods, such as replica exchange (52,53) and metadynamics (31,54). The restraints were imposed by adding the experimentally driven energy terms VCSA and VDC (see the Supporting Material) to the standard force fields, VFF.

| (1) |

In this study, CSA and DC restraints have been imposed either on the individual systems or as ensemble-averaged values over simultaneously evolving copies, i.e., replicas, of the system (see the Supporting Material). Replica average simulations are optimal to account for multiple conformations in fast exchange. The employment of replicas has been tested for a number of NMR and other biophysical restraints (31,55–57), including CSA and DC (45,46).

Structural models for CSA and DC

Chemical shift anisotropy is defined using a 3 × 3 tensor (the chemical shift tensor) that describes the interaction of the nuclear spin with the external magnetic field. This tensor is dependent on the local environment around the nuclear spin and thus encodes the local geometry for any given nucleus. Studies using a variety of approaches, including static unoriented samples (powder pattern) generated by ssNMR (58) and in solution NMR (59), have shown that such a tensor for the amide nitrogen in protein can be defined by the tensor elements given in Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material (δ11, δ22, δ33), where, according to the convention of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, δ33 ≥ δ22 ≥ δ11.

The magnitude and orientation of the CSA tensor may vary significantly for different amide groups. However, experimentally it is found that apart from glycine, most of the other tensors have only a small variability of ∼±5 ppm (60). Especially for membrane proteins, such variability is minimal because of the similarity of the environment around transmembrane residues. Nevertheless, a ±5 ppm error irrespective of the experimental error, which is typically of the order of 2–3 ppm, must be included to account for this variability. For the anisotropic chemical shift, we used the following mathematical formula:

| (2) |

where the δ11, δ22, and δ33 are the experimentally determined components (in ppm) of the 15N amide chemical shift tensor in the principal axis frame (PAF), and α and β are the experimentally determined Euler angles (in degrees) used to transform from the laboratory frame to PAF (19). We employed constant values of the chemical shift tensor using standard parameters (δ11= 64.0, δ22= 76.0, δ33= 216.9 for nonglycine, and δ11 = 46.5, δ22 = 66.3, δ33 = 211.6 for glycine residues). Fixed values of the tensor may represent a minor source of error, as ab initio studies have shown that CSA tensors may be subject to variation due to different factors (94–96). The harmonic function associated with our restraints, however, implements a 5 ppm error range and takes into account the variability of the tensor in addition to the experimental error.

Unlike the CSA, the DC tensor for amide groups (N-H) is highly uniform, depending only on the N-H bond length and its orientation with respect to external magnetic field (Fig. S1):

| (3) |

where ζDC is set to 10.52 kHz. Any motion corresponding to rapid changes in orientation of N-H bond vector with respect to the magnetic field will scale down the DCs from the maximum value. Global motions of the proteins such as rotations around the bilayer normal and/or overall rotational motion of the bicelle need to be taken into account using a uniform scaling factor for all the restraints. For bicelles, the scaling factor was found to be 0.8 (21,61).

Results

Accuracy of CSA and DC as restraints in MD simulations

The orientational properties (i.e., topology) of TM α-helices are best described in terms of tilt and azimuthal angles (Fig. 1). To test whether CSA and DC restraints efficiently instruct the simulations to adopt the target topology, we carried out a series of single-replica restrained simulations of SLN in the lipid bilayer, targeting different values of tilt and azimuthal angles. These in silico experiments were performed by orienting a target SLN structure with tilt and azimuthal angles of 8° and 67°, respectively. Using this target model, we back-calculated a set of CSA and DC data and imposed these as experimental data in a restrained MD simulation, starting from a conformation of SLN equilibrated in DOPC bilayer (starting tilt and azimuthal angles of 23° and 29°, respectively). The restraints were imposed using 2 ppm and 0.4 kHz as uncertainties for CSA and DC, respectively. With the employed force field and MD setting, unrestrained simulations fluctuate in such a way as to adopt variable tilt angles in the range 25–40° and variable azimuthal angles in the range 20–60° (Fig. S2). As a result, the agreement between the back-calculated CSA and DC data from the unrestrained MD and those from the target structure is rather poor (Fig. S3 A). In contrast, the simulated structures performed with CSA and/or DC restraints rapidly converge to the correct topology with low Q factor values (Fig. S3, B–D). The two types of restraints are correlated; that is, while imposing CSA as a restraint, we observe a reduction of the Q factor for DC restraints, and vice versa (Fig. S3 B). The best agreement with the tilt and azimuthal angles is obtained when both CSA and DC restraints are imposed simultaneously. In the latter case, the average Q factors plateau out at 0.025 ± 0.002 and 0.074 ± 0.005 for CSA and DC, respectively. These simulations converged and show an excellent agreement with the tilt and azimuthal angles of the target structure (Fig. 1 A). In particular, when using CSA and DC restraints, tilt angles from the MD simulation converge to the target values within the first 10 ns, i.e., when the system is still in the equilibration phase and before the final values of the α constants are reached. Very good, but slower, convergence is also observed for the azimuthal angle, suggesting that it is necessary to include both CSA and DC data to achieve a highly accurate characterization of the topology of SLN (Fig. 1 B). Conversely, by using either DC or CSA restraints alone, the convergence of the azimuthal angle is poor, as monitored over 50 ns of MD calculations.

Figure 1.

Tilt and azimuthal angles in restrained MD simulations. Simulations employed CSA (green), DC (orange), and CSA + DC (red) restraints. (a) Evolution of tilt angles during 50 ns of MD simulations. The angles are calculated between the axis of the α-helix and the B0 magnetic field vector oriented in the Z-dimension and perpendicular to the lipid bilayer. (b) The azimuthal angle is defined on the plane perpendicular to the helix axis. The angle is calculated between the projection of the Cα atom of Trp-23 on the helix axis and the plane defined by the helix axis and B0. To see this figure in color, go online.

Additional restrained simulations were carried out, changing the target tilt and azimuthal angles systematically (Fig. S4). From these data, we conclude that regardless of the orientation of the target structure, the restraints help the simulated trajectories of SLN to converge toward the target tilt and azimuthal angles (Fig. S4). This analysis also shows that the CSA and DC are highly effective restraints for MD simulations of membrane proteins and can be employed to obtain correct topologies and large-scale conformational transitions of secondary structure elements with respect to the membrane bilayer.

Refinement of SLN structural ensembles using experimental CSA and DC

Using the optimal setting of CSA and DC restraints applied simultaneously (Fig. 1), we refined the structural ensemble of sarcolipin by using experimental CSA and DC recorded in DMPC-POPC-D6PC bicelles (10,36). The experimental errors utilized for these simulations were 5 ppm and 0.5 kHz for CSA and DC data, respectively. To validate the convergence and reproducibility of the method, we performed five different MD simulations in a DOPC lipid bilayer, starting from SLN conformations at different tilt (12°, 19°, 30°, 42°, and 51°) and azimuthal (80°, 38°, 17°, 8°, and 103°) angles. All five trajectories converged to the same tilt and azimuthal angles (Fig. 2, A and B), with the SD for the average tilt and azimuthal angles among the five refinements at 0.3° and 1.8°, respectively. The resulting ensemble (Fig. 2 C) shows average angles of 23° for the tilt and 29° for the azimuthal angles. These angles are in good agreement with those predicted from the experimental data using analytical expressions (62). The back-calculated CSA and DC from the ensemble are in excellent agreement with the experimental data, with Q factors of 0.025 and 0.76 and standard deviations of 2.34 ppm and 0.48 kHz, respectively (Fig. 2, D and E). In contrast, the corresponding unrestrained simulations show Q factors of 0.66 and 0.147 and standard deviations of 10.72 ppm and 1.09 kHz for CSA and DC, respectively. In addition to the convergence in topological orientations, the five simulations show a significant convergence of the structure of SLN, as shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Structural ensemble refinement of SLN in a lipid bilayer by CSA and DC restrained simulations. (a) Evolution of the tilt angles during the structural refinements. The initial tilt angles were 11.8° (black), 19.2° (red), 30.4° (orange), 41.9° (green), and 50.8° (blue). (b) Evolution of the azimuthal angles during the structural refinements. The initial azimuthal angles were 80.3° (black), 38.6° (red), 17.3° (orange), 7.7° (green), and 102.5° (blue). Curve fitting using first-order exponential decays (yellow lines in a and b). (c) Refined structural ensemble of SLN in a lipid bilayer. (d and e) Experimental (black) versus calculated (red) CSA and DC values. Experimental errors for CSA and DC are 5 ppm and 0.5 kHz, respectively. Error bars in calculated CSA and DC correspond to standard deviations. (f) Amide S2 values from unrestrained (blue) and restrained (orange) MD simulations and 15N relaxation experiments (green). (g) Root mean-square fluctuations (RMSFs) calculated on Cα atoms of SLN in the unrestrained (blue) and restrained (orange) MD simulations. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 1.

RMSD values between restrained-MD samplings

| MD 1 | MD 2 | MD 3 | MD 4 | MD 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD 1 | — | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.97 | 0.72 |

| MD 2 | 1.68 | — | 0.39 | 0.52 | 0.33 |

| MD 3 | 1.50 | 1.23 | — | 0.50 | 0.37 |

| MD 4 | 2.14 | 1.89 | 1.32 | — | 0.46 |

| MD 5 | 1.77 | 1.43 | 1.38 | 1.95 | — |

Average values of the RMSDs calculated between structures of two ensembles. Top corner of the matrix reports RMSD values calculated using Cα atoms of residues 6–27. Bottom corner reports values calculated using all Cα atoms.

Remarkably, the convergence of the restrained simulations as monitored by the tilt and azimuthal angles is independent of the nature of the explicit lipids employed. Indeed, additional simulations using different parameterizations (63) of DOPC lipids (Fig. S5) or different lipid bilayers composed of POPC lipids (64) (Fig. S6) converged toward the same tilt and azimuthal angles. This finding indicates that the dominant factor in the orientation and topology of TM helices in our restrained simulation is the information contained in experimental CSA- and DC-restraints. This result provides striking support for the study of the dynamics and structure of membrane proteins via restrained MD simulations and indicates that the restraints are indeed powerful means to overcome the intrinsic limitations of force fields to achieve an accurate characterization of the topology and fluctuations of TM helices.

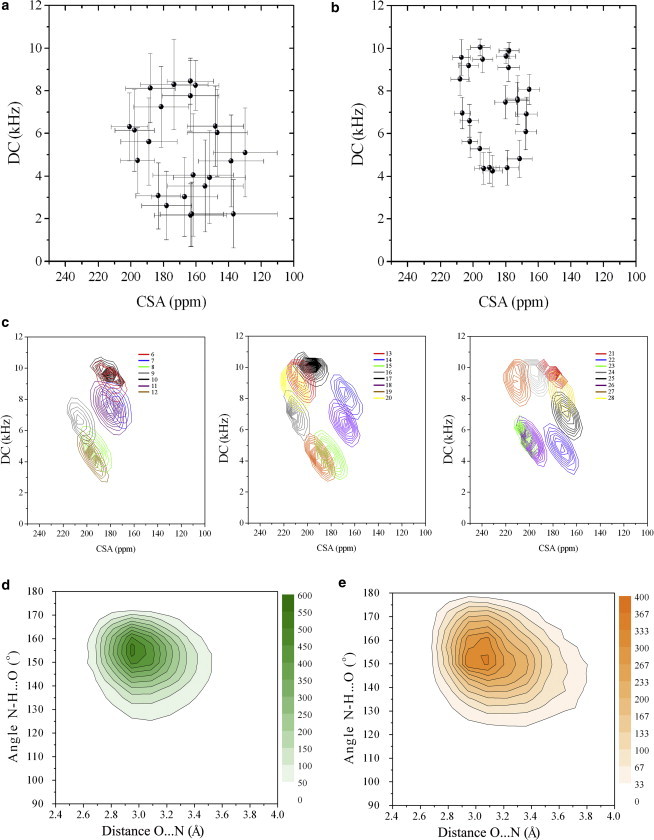

We also analyzed the effects of the CSA and DC restraints on the local dynamics of amide groups. We found that the calculated order parameters (S2) of the restrained ensemble are higher in the helical part of the protein, which is more rigid for residues 6–27 with respect to the unrestrained simulations (Fig. 2 F), whereas the termini are more flexible (lower S2 values). This trend, confirmed by the Cα root mean-square fluctuations (RMSFs; Fig. 2 G), is in closer agreement with experimental order parameters determined in micelles by solution NMR (Fig. 2 F). Interestingly, the restrained simulations display a higher degree of ideality of the SLN helical region (Fig. S7). The latter is not surprising, since Cross and co-workers have demonstrated that the TM domains of membrane proteins are more regular than their soluble counterparts (60,65). Interestingly, in the absence of structural restraints, the helical region of SLN (residues 6–27) in lipid membranes has a tendency to break into two different regions and adopt a curved structure. In contrast, when experimental restraints are imposed, we observed a helical conformation closer to an ideal helix. Moreover, restrained simulations show a better agreement with the canonical distances and angles that characterize hydrogen bonds in ideal helices (Fig. 3, D and E). Overall, these findings underline the efficiency of CSA and DC restraints in correcting the imperfection of force fields toward an accurate description of the conformational landscapes of membrane proteins embedded in realistic lipid membranes.

Figure 3.

PISEMA plot for amides of residues 6–28 of SLN. (a) Unrestrained simulations and (b) CSA and DC restrained simulations. Note that these plots are not calculated using 10° torsion-angle averaging as in Shi et al. (62), but using instantaneous conformations. Error bars indicate the mean ± SD of the values. (c) Curve levels population distributions of CSA and DC values from the restrained simulations in the PISEMA plot. (d and e) Local geometry of main-chain H-bonds assessed by the angle between N, H, and O and the distance between N and O atoms in unrestrained (d) and restrained (e) simulations. The example focuses on the H-bond between residues 16 and 20, but consistent results are found throughout the SLN helix. To see this figure in color, go online.

We previously pointed out key side-chain interactions that stabilize SLN structure in lipid membranes (62). All of these interactions are reproduced in both the unrestrained and restrained simulations carried out here; therefore, it is not possible to establish the impact of the restraints on the side-chain conformations, as we established in the case of residual dipolar couplings restrained ensembles for ribonuclease A (66).

We then compared the back-calculated polarization inversion spin exchange at magic angle (PISEMA) spectra from both restrained and unrestrained MD simulations. As expected, the CSA and DC restraints utilized in the simulations result in a more regular oscillatory pattern of the CSA and DC (65,67) typical of ideal helices (Fig. 3, A–C). Also, we found that the spread of the DC and CSA values around the average in the restrained MD simulations is much smaller than that in the corresponding unrestrained simulations (Fig. 3, A and B). A possible explanation is that without DC and CSA restraints, the calculations overestimate the fluctuations of the amide group dynamics (68), predicting larger line widths for the PISEMA resonances. Interestingly, after removing the contribution of the mosaic spread and tilt and azimuthal angle fluctuations, the spread of the DC and CSA values around the average values in the restrained MD simulations (Fig. 3 C) is similar to the experimental line widths measured in the PISEMA experiments. Although this is far from a quantitative assessment of the line widths, these results suggest that restrained simulations may provide a quantitative interpretation of the conformational dynamics of membrane proteins from the analysis of the CSA/DC patterns.

Refinement of PLN conformational equilibrium using experimental CSA and DC

Characterizing the dynamics and topology of PLN is crucial to understanding its regulatory function for cardiac muscle relaxation (50,69–71). PLN exists as a pentamer in the sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane and disassembles into monomers that interact with SERCA (8,72–74). PLN possesses a metamorphic N-terminal cytoplasmic domain that folds upon interaction with the lipid membrane (50,69–71,75). Both solution and solid-state NMR identified two major conformational states: T and R states. In the T state, domain Ia (residues 1–16) is associated with the membrane and adopts a helical conformation, whereas in the R state, domain Ia is completely unfolded and membrane-dissociated. Additional states between the T and R states, namely T′ and R′, could be identified by relaxation dispersion measurements (76) and other types of experiments (70,77,78). PLN conformational equilibrium is a fundamental element for SERCA regulation, where the interplay between the T and R states ensures proper regulation, as well as recognition and phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA), an event that reverses SERCA inhibition by PLN, restoring its apparent Ca2+ affinity (71,79,80). Indeed, the employment of proper membrane mimetic systems, such as lipid membranes, is of paramount importance, since micelles alter the populations along this equilibrium (4,37,81). Ensemble simulations using replica-averaged restraints are able to describe the equilibrium between different conformations that contribute via Boltzmann weights to the ensemble-averaged experimental data in explicit membrane environments. We found that the optimal number of replicas was 16 (see the Supporting Material), and subsequently ran 16-replica-ensemble restrained simulations based collectively on 100 annealing cycles (0.5 ns per replica) with temperatures ranging from 300 K to 400 K (66,82). We refined the structural ensemble of PLN in its T state using CSA and DC data (38). As a starting conformation, we chose one conformer from the structural ensemble calculated using XPLOR-NIH (47). The system included PLN in DOPC bilayers with explicit water molecules (see the Supporting Material).

The resulting structural ensemble shows well defined tilt (23.4 ± 2.9) and azimuthal (202.6 ± 7.3) angles for the TM domain of the protein (domain II), which is in agreement with the static fit carried out on the initial solid-state NMR data (83). The N-terminal cytoplasmatic domain features a large variety of orientations parallel to the lipid surface (Fig. S8). By analyzing the distribution of conformations explored in our calculations, we found that most conformers show the characteristics of the T state, with an α-helical fold of domain Ia (residues 1–16) that adopts the typical orientation of amphipathic helices with hydrophobic residues pointing toward the inner core of the membrane and hydrophilic residues pointing toward the bulk water.

In Fig. 4, the T conformation corresponds to a relatively stable helix in domain Ia, with approximately eight i and i + 4 backbone hydrogen bonds with extensive protein/lipids contacts. Although the majority of the conformations lie in the T-state region of the distribution, a small population of substates reveals the structural transitions toward the R state, with several residues of domain Ia disrupting H-bonds and detaching from the lipid membrane surface. Note that the structural refinements carried out with XPLOR-NIH converged to a unique folded state, with no conformers showing unfolding (i.e., no conformers in the R state) (10,38,62). This finding is of great significance, as it shows that the conversion from the T to the R state follows an unfolding pathway of domain Ia with subsequent detachment from the lipid surface. The unfolding of domain Ia was hypothesized in the denaturation experiments carried out in detergent micelles but was never demonstrated (69).

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional distribution of T and R states for PLN in explicit lipid membranes calculated using two reaction coordinates. The first is the number of H-bonds between residues i and i + 4 in domain Ia of PLN (residues 1–16). The second is the number of intermolecular contacts between lipids and protein atoms in domain Ia. Only heavy atoms are considered in this calculation. The curves have been calculated by interpolating the population values in discrete bins of the 2D space. A plot reporting the discrete populations is shown in Fig. S10. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Atomistic MD simulations are essential for interpreting molecular motions of biomacromolecules (84). In the past few decades, unrestrained MD simulations have contributed greatly toward our understanding of molecular motions and their connection to biological function (84). However, the limitations of the classical force fields caused by the simplified treatment of intra- and intermolecular interactions, as well as the lack of polarizable force fields, cause the molecular systems to explore phase spaces that are not compatible with the experimental data (85). It has been shown that force field deficiencies or insufficient sampling may cause the molecular systems to identify conformations that are unlikely to be populated in real systems (85). Structural restraints derived from experimental data can supply additional information, biasing the conformational sampling toward a more realistic energy landscape (28,30). For soluble proteins, this is possible by using chemical shifts (31), residual DCs (55,66), H/D exchange data (57), and other NMR observables. In the case of membrane proteins, however, these restrained MD simulations are still sparse due to the paucity of experimental data available.

For oriented ssNMR data, membrane protein dynamics have been indirectly derived from theoretical models used to fit NMR parameters such as DC and CSA. Valuable information on protein dynamics has also been extracted using unified theory of the NMR line shapes of aligned membrane proteins (21). These methods, however, are all model-based, and can in principle misinterpret the orientational information and/or underestimate the conformational dynamics. To overcome this problem, with a similar approach to solution-NMR restrained MD (28–31,45,55–57), we here implemented DC and CSA in GROMACS and used them with the AMBER99sb force field (86–88) and TIP4pEW (89) to simulate the dynamics of SLN in lipid membranes. We found that experimental restraints such as DC and CSA dramatically improve the dynamical description of membrane proteins. These are particularly effective in driving the topological properties of the protein, including the tilt and azimuthal angles. Moreover, backbone torsion angles, as well as the hydrogen bonds in the helical segment of SLN, are much closer to those of ideal helices than in the unrestrained sampling. The restraints also have an effect on the local motions by improving the agreement between back-calculated and experimental order parameters of SLN. When heterogeneous systems are studied, ensemble-averaged restraints can be effectively used to refine the structures of different conformational states in equilibrium and to quantify their populations. In this study, we showed the accuracy of this approach by refining the structural ensemble of PLN and pointing out the nature of its conformational change from the T to the R state. Capturing these structural conversions and motions is important not only for understanding PLN biological function, but also for designing mutants that promote loss-of-function states for possible use in gene therapy (90,91).

In conclusion, by using experimental restraints from oriented ssNMR in MD simulations in explicit solvent and lipid environments, we produced structural ensembles of SLN and PLN that accurately reproduce the dynamical properties of these membrane proteins. Because of the increasing availability of experimental data on the structure and dynamics of lipid-emended proteins (8,10,11,17,50,92,93,96,97), the constant optimization of the force fields, and the definition of new enhanced sampling methods, the combination of oriented ssNMR experiments and MD simulations represents a highly promising approach to characterize the dynamical behavior of membrane proteins, including those dynamical states that exist in equilibrium between multiple conformations and whose populations are finely regulated by complex mechanisms that direct bimolecular trafficking at cellular membranes.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by the European Molecular Biology Organisation and the Leverhulme Trust (A.D.), and by a National Institutes of Health grant (GM64742 to G.V.) . and by the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute.

Contributor Information

Alfonso De Simone, Email: adesimon@imperial.ac.uk.

Gianluigi Veglia, Email: vegli001@umn.edu.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Tamm L.K. Wiley; Weinheim, Germany: 2005. Protein Lipid Interactions: From Membrane Domains to Cellular Networks. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Good D.B., Wang S., Ladizhansky V. Conformational dynamics of a seven transmembrane helical protein anabaena sensory rhodopsin probed by solid-state NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:2833–2842. doi: 10.1021/ja411633w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vostrikov V.V., Grant C.V., Koeppe R.E., 2nd On the combined analysis of ²H and 15N/1H solid-state NMR data for determination of transmembrane peptide orientation and dynamics. Biophys. J. 2011;101:2939–2947. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray D.T., Das N., Cross T.A. Solid state NMR strategy for characterizing native membrane protein structures. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:2172–2181. doi: 10.1021/ar3003442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veglia G., Traaseth N.J., Shi L., Verardi R., Gopinath T. The hybrid solution/solid-state NMR method for membrane protein structure determination. In: Egelman E.H., editor. Comprehensive Biophysics. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2012. pp. 182–198. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das N., Murray D.T., Cross T.A. Lipid bilayer preparations of membrane proteins for oriented and magic-angle spinning solid-state NMR samples. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:2256–2270. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang S., Munro R.A., Ladizhansky V. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy structure determination of a lipid-embedded heptahelical membrane protein. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1007–1012. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verardi R., Shi L., Veglia G. Structural topology of phospholamban pentamer in lipid bilayers by a hybrid solution and solid-state NMR method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:9101–9106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016535108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vostrikov V.V., Mote K.R., Veglia G. Structural dynamics and topology of phosphorylated phospholamban homopentamer reveal its role in the regulation of calcium transport. Structure. 2013;21:2119–2130. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mote K.R., Gopinath T., Veglia G. Determination of structural topology of a membrane protein in lipid bilayers using polarization optimized experiments (POE) for static and MAS solid state NMR spectroscopy. J. Biomol. NMR. 2013;57:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9766-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Can T.V., Sharma M., Cross T.A. Magic angle spinning and oriented sample solid-state NMR structural restraints combine for influenza A M2 protein functional insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:9022–9025. doi: 10.1021/ja3004039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castellani F., van Rossum B., Oschkinat H. Structure of a protein determined by solid-state magic-angle-spinning NMR spectroscopy. Nature. 2002;420:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature01070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rienstra C.M., Hohwy M., Griffin R.G. Determination of multiple torsion-angle constraints in U-13C,15N-labeled peptides: 3D 1H-15N-13C-1H dipolar chemical shift NMR spectroscopy in rotating solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11908–11922. doi: 10.1021/ja020802p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reif B., Jaroniec C.P., Griffin R.G. 1H-1H MAS correlation spectroscopy and distance measurements in a deuterated peptide. J. Magn. Reson. 2001;151:320–327. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wylie B.J., Sperling L.J., Rienstra C.M. Ultrahigh resolution protein structures using NMR chemical shift tensors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:16974–16979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103728108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park S.H., Das B.B., Opella S.J. Structure of the chemokine receptor CXCR1 in phospholipid bilayers. Nature. 2012;491:779–783. doi: 10.1038/nature11580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das B.B., Nothnagel H.J., Opella S.J. Structure determination of a membrane protein in proteoliposomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2047–2056. doi: 10.1021/ja209464f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mesleh M.F., Veglia G., Opella S.J. Dipolar waves as NMR maps of protein structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:4206–4207. doi: 10.1021/ja0178665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramamoorthy A., Wei Y., Lee D.K. Advances in Solid State NMR Studies of Materials and Polymers. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2004. PISEMA solid state NMR spectroscopy; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quine J.R., Achuthan S., Cross T.A. Intensity and mosaic spread analysis from PISEMA tensors in solid-state NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 2006;179:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nevzorov A.A. Orientational and motional narrowing of solid-state NMR lineshapes of uniaxially aligned membrane proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:15406–15414. doi: 10.1021/jp2092847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolf T.B., Roux B. The binding site of sodium in the gramicidin A channel: comparison of molecular dynamics with solid-state NMR data. Biophys. J. 1997;72:1930–1945. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78839-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fowler P.W., Sansom M.S.P. The pore of voltage-gated potassium ion channels is strained when closed. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1872. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sayadi M., Feig M. Role of conformational sampling of Ser16 and Thr17-phosphorylated phospholamban in interactions with SERCA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1828:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu H., Schulten K. Membrane sculpting by F-BAR domains studied by molecular dynamics simulations. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1002892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindorff-Larsen K., Piana S., Shaw D.E. How fast-folding proteins fold. Science. 2011;334:517–520. doi: 10.1126/science.1208351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ketchem R., Roux B., Cross T. High-resolution polypeptide structure in a lamellar phase lipid environment from solid state NMR derived orientational constraints. Structure. 1997;5:1655–1669. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vendruscolo M., Dobson C.M. Towards complete descriptions of the free-energy landscapes of proteins. Philos. Trans. A. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2005;363:433–450. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2004.1501. discussion 450–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neudecker P., Robustelli P., Kay L.E. Structure of an intermediate state in protein folding and aggregation. Science. 2012;336:362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1214203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roux B., Weare J. On the statistical equivalence of restrained-ensemble simulations with the maximum entropy method. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138:084107. doi: 10.1063/1.4792208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Camilloni C., Schaal D., De Simone A. Energy landscape of the prion protein helix 1 probed by metadynamics and NMR. Biophys. J. 2012;102:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guerry P., Salmon L., Blackledge M. Mapping the population of protein conformational energy sub-states from NMR dipolar couplings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013;52:3181–3185. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen Y., Lange O., Bax A. Consistent blind protein structure generation from NMR chemical shift data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:4685–4690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800256105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buffy J.J., Buck-Koehntop B.A., Veglia G. Defining the intramembrane binding mechanism of sarcolipin to calcium ATPase using solution NMR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;358:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zamoon J., Mascioni A., Veglia G. NMR solution structure and topological orientation of monomeric phospholamban in dodecylphosphocholine micelles. Biophys. J. 2003;85:2589–2598. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74681-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mote K.R., Gopinath T., Veglia G. Multidimensional oriented solid-state NMR experiments enable the sequential assignment of uniformly 15N labeled integral membrane proteins in magnetically aligned lipid bilayers. J. Biomol. NMR. 2011;51:339–346. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Traaseth N.J., Verardi R., Veglia G. Spectroscopic validation of the pentameric structure of phospholamban. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14676–14681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701016104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Traaseth N.J., Shi L., Veglia G. Structure and topology of monomeric phospholamban in lipid membranes determined by a hybrid solution and solid-state NMR approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:10165–10170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904290106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Odermatt A., Becker S., MacLennan D.H. Sarcolipin regulates the activity of SERCA1, the fast-twitch skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12360–12369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bal N.C., Maurya S.K., Periasamy M. Sarcolipin is a newly identified regulator of muscle-based thermogenesis in mammals. Nat. Med. 2012;18:1575–1579. doi: 10.1038/nm.2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahoo S.K., Shaikh S.A., Periasamy M. Sarcolipin protein interaction with sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) is distinct from phospholamban protein, and only sarcolipin can promote uncoupling of the SERCA pump. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:6881–6889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.436915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toyoshima C., Iwasawa S., Inesi G. Crystal structures of the calcium pump and sarcolipin in the Mg2+-bound E1 state. Nature. 2013;495:260–264. doi: 10.1038/nature11899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winther A.-M.L., Bublitz M., Buch-Pedersen M.J. The sarcolipin-bound calcium pump stabilizes calcium sites exposed to the cytoplasm. Nature. 2013;495:265–269. doi: 10.1038/nature11900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorski P.A., Glaves J.P., Young H.S. Sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) inhibition by sarcolipin is encoded in its luminal tail. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:8456–8467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.446161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Im W., Jo S., Kim T. An ensemble dynamics approach to decipher solid-state NMR observables of membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng X., Jo S., Im W. NMR-based simulation studies of Pf1 coat protein in explicit membranes. Biophys. J. 2013;105:691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi L., Traaseth N.J., Veglia G. A refinement protocol to determine structure, topology, and depth of insertion of membrane proteins using hybrid solution and solid-state NMR restraints. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;44:195–205. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9328-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marassi F.M., Opella S.J. Simultaneous assignment and structure determination of a membrane protein from NMR orientational restraints. Protein Sci. 2003;12:403–411. doi: 10.1110/ps.0211503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bertram R., Quine J.R., Cross T.A. Atomic refinement using orientational restraints from solid-state NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 2000;147:9–16. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gustavsson M., Traaseth N.J., Veglia G. Probing ground and excited states of phospholamban in model and native lipid membranes by magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hess B., Kutzner C., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sugita Y., Okamoto Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999;314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Simone A., Kitchen C., Frenkel D. Intrinsic disorder modulates protein self-assembly and aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:6951–6956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118048109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laio A., Parrinello M. Escaping free-energy minima. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:12562–12566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202427399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Simone A., Richter B., Vendruscolo M. Toward an accurate determination of free energy landscapes in solution states of proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3810–3811. doi: 10.1021/ja8087295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gianni S., Ivarsson Y., Vendruscolo M. Structural characterization of a misfolded intermediate populated during the folding process of a PDZ domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:1431–1437. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Simone A., Dhulesia A., Dobson C.M. Experimental free energy surfaces reveal the mechanisms of maintenance of protein solubility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:21057–21062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112197108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramamoorthy A., Wu C.H., Opella S.J. Magnitudes and orientations of the principal elements of the 1H chemical shift, 1H-15N dipolar coupling, and 15N chemical shift interaction tensors in 15Nε1-tryptophan and 15Nπ-histidine side chains determined by three-dimensional solid-state NMR spectroscopy of polycrystalline samples. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:10479–10486. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yao L., Grishaev A., Bax A. Site-specific backbone amide 15N chemical shift anisotropy tensors in a small protein from liquid crystal and cross-correlated relaxation measurements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4295–4309. doi: 10.1021/ja910186u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim S., Cross T.A. Uniformity, ideality, and hydrogen bonds in transmembrane α-helices. Biophys. J. 2002;83:2084–2095. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Park S.H., De Angelis A.A., Opella S.J. Three-dimensional structure of the transmembrane domain of Vpu from HIV-1 in aligned phospholipid bicelles. Biophys. J. 2006;91:3032–3042. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.087106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shi L., Cembran A., Veglia G. Tilt and azimuthal angles of a transmembrane peptide: a comparison between molecular dynamics calculations and solid-state NMR data of sarcolipin in lipid membranes. Biophys. J. 2009;96:3648–3662. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jämbeck J.P.M., Lyubartsev A.P. Derivation and systematic validation of a refined all-atom force field for phosphatidylcholine lipids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:3164–3179. doi: 10.1021/jp212503e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jämbeck J.P.M., Lyubartsev A.P. An extension and further validation of an all-atomistic force field for biological membranes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:2938–2948. doi: 10.1021/ct300342n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Page R.C., Kim S., Cross T.A. Transmembrane helix uniformity examined by spectral mapping of torsion angles. Structure. 2008;16:787–797. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.De Simone A., Montalvao R.W., Vendruscolo M. Determination of conformational equilibria in proteins using residual dipolar couplings. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:4189–4195. doi: 10.1021/ct200361b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mascioni A., Veglia G. Theoretical analysis of residual dipolar coupling patterns in regular secondary structures of proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12520–12526. doi: 10.1021/ja0354824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Straus S.K., Scott W.R.P., Watts A. Assessing the effects of time and spatial averaging in 15N chemical shift/15N-1H dipolar correlation solid state NMR experiments. J. Biomol. NMR. 2003;26:283–295. doi: 10.1023/a:1024098123386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gustavsson M., Traaseth N.J., Veglia G. Lipid-mediated folding/unfolding of phospholamban as a regulatory mechanism for the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;408:755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karim C.B., Zhang Z., Thomas D.D. Phosphorylation-dependent conformational switch in spin-labeled phospholamban bound to SERCA. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;358:1032–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gustavsson M., Verardi R., Veglia G. Allosteric regulation of SERCA by phosphorylation-mediated conformational shift of phospholamban. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:17338–17343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303006110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Robia S.L., Campbell K.S., Thomas D.D. Förster transfer recovery reveals that phospholamban exchanges slowly from pentamers but rapidly from the SERCA regulatory complex. Circ. Res. 2007;101:1123–1129. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.159947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Becucci L., Cembran A., Veglia G. On the function of pentameric phospholamban: ion channel or storage form? Biophys. J. 2009;96:L60–L62. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reddy L.G., Jones L.R., Thomas D.D. Depolymerization of phospholamban in the presence of calcium pump: a fluorescence energy transfer study. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3954–3962. doi: 10.1021/bi981795d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomas D.D., Reddy L.G., Stamm J. Direct spectroscopic detection of molecular dynamics and interactions of the calcium pump and phospholamban. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;853:186–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Traaseth N.J., Veglia G. Probing excited states and activation energy for the integral membrane protein phospholamban by NMR CPMG relaxation dispersion experiments. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Traaseth N.J., Thomas D.D., Veglia G. Effects of Ser16 phosphorylation on the allosteric transitions of phospholamban/Ca2+-ATPase complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;358:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li M., Cornea R.L., Thomas D.D. Phosphorylation-induced structural change in phospholamban and its mutants, detected by intrinsic fluorescence. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7869–7877. doi: 10.1021/bi9801053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wegener A.D., Simmerman H.K., Jones L.R. Phospholamban phosphorylation in intact ventricles. Phosphorylation of serine 16 and threonine 17 in response to β-adrenergic stimulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:11468–11474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hou Z., Kelly E.M., Robia S.L. Phosphomimetic mutations increase phospholamban oligomerization and alter the structure of its regulatory complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:28996–29003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804782200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miao Y., Qin H., Cross T.A. M2 proton channel structural validation from full-length protein samples in synthetic bilayers and E. coli membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:8383–8386. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.De Simone A., Gustavsson M., Vendruscolo M. Structures of the excited states of phospholamban and shifts in their populations upon phosphorylation. Biochemistry. 2013;52:6684–6694. doi: 10.1021/bi400517b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Traaseth N.J., Ha K.N., Veglia G. Structural and dynamic basis of phospholamban and sarcolipin inhibition of Ca2+-ATPase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3–13. doi: 10.1021/bi701668v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Karplus M., McCammon J.A. Molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:646–652. doi: 10.1038/nsb0902-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Robustelli P., Stafford K.A., Palmer A.G., 3rd Interpreting protein structural dynamics from NMR chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:6365–6374. doi: 10.1021/ja300265w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hornak V., Abel R., Simmerling C. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins. 2006;65:712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Best R.B., Buchete N.-V., Hummer G. Are current molecular dynamics force fields too helical? Biophys. J. 2008;95:L07–L09. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.132696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lindorff-Larsen K., Piana S., Shaw D.E. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins. 2010;78:1950–1958. doi: 10.1002/prot.22711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Horn H.W., Swope W.C., Head-Gordon T. Development of an improved four-site water model for biomolecular simulations: TIP4P-Ew. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;120:9665–9678. doi: 10.1063/1.1683075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ha K.N., Traaseth N.J., Veglia G. Controlling the inhibition of the sarcoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase by tuning phospholamban structural dynamics. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:37205–37214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ha K.N., Gustavsson M., Veglia G. Tuning the structural coupling between the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of phospholamban to control sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) function. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2012;33:485–492. doi: 10.1007/s10974-012-9319-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tang M., Nesbitt A.E., Rienstra C.M. Structure of the disulfide bond generating membrane protein DsbB in the lipid bilayer. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:1670–1682. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pandey M.K., Vivekanandan S., Ramamoorthy A. Determination of 15N chemical shift anisotropy from a membrane-bound protein by NMR spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:7181–7189. doi: 10.1021/jp3049229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Poon A., Birn J., Ramamoorthy A. How does an amide-N chemical shift tensor vary in peptides? J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:16577–16585. doi: 10.1021/jp0471913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee D.K., Wildman K.H., Ramamoorthy A. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy of aligned lipid bilayers at low temperatures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2318–2319. doi: 10.1021/ja039077o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pandey M.K., Vivekanandan S., Ramamoorthy A. Cytochrome-P450-cytochrome-b5 interaction in a membrane environment changes 15N chemical shift anisotropy tensors. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013;117:13851–13860. doi: 10.1021/jp4086206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dürr U.H., Gildenberg M., Ramamoorthy A. The magic of bicelles lights up membrane protein structure. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:6054–6074. doi: 10.1021/cr300061w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schwieters C.D., Kuszewski J.J., Clore G.M. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Siu S.W.I., Vácha R., Böckmann R.A. Biomolecular simulations of membranes: physical properties from different force fields. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:125103. doi: 10.1063/1.2897760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wolf M.G., Hoefling M., Groenhof G. g_membed: efficient insertion of a membrane protein into an equilibrated lipid bilayer with minimal perturbation. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:2169–2174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:014101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., Haak J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hess B., Bekker H., Fraaije J.G.E.M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.