Abstract

Background:

There is a known association between congenital heart disease (CHD) and other congenital anomalies (CA). These associations have been altered by changes in prenatal factors in recent time. We reviewed the largest database of inpatient hospitalization information and analyzed the current association between common CHD diagnoses and other congenital anomalies.

Materials and Methods:

Case-control study design. We reviewed the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 1998 to 2008 and identified all live births with CHD diagnosis (case) and live births without CHD diagnosis (control). We compared prevalence of associated congenital anomalies between the case and control groups.

Results:

Our cohort consisted of 97,154 and 12,078,482 subjects in the case and control groups, respectively. In the CHD population, prevalence of non-syndromic congenital anomaly (NSCA), genetic syndrome (GS), and overall extra-cardiac congenital anomaly (CA) were 11.4, 2.2, and 13.6%, respectively. In the control group, prevalence of NSCA, GS, and CA were 6.7, 0.3, and 7.0%, respectively. NSCA (odds ratio (OR): 1.88, confidence interval (CI): 1.73-1.94), GS (OR 2.52, CI 2.44-2.61), and overall CA (OR: 2.01, CI: 1.97-2.14) were strongly associated with CHD. Prevalence of GS and multiple organ-system CA decreased significantly over the study period.

Conclusions:

This is the largest and most comprehensive population-based study evaluating association between CHD and extra-cardiac malformation (ECM) in newborns. There was significant decrease in prevalence of GS and multiple CA over the study period.

Keywords: Congenital anomalies, epidemiology, extra cardiac, newborn, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Previous studies have shown association between congenital heart disease (CHD) and other congenital anomalies (CAs) and genetic syndromes (GSs).[1,2,3,4,5,6,7] Depending on the severity of CHD diagnosis, the clinical course may range from spontaneous closure of defect as seen with small septal defects to a lifelong need for medical and surgical interventions.[8,9] The presence of non-cardiac CAs also significantly impacts the natural history and clinical course of CHD as these patients may require medical and/or surgical interventions independent of their cardiac pathology.

Epidemiology of CHD is well-described.[2,10,11,12] However, we believe that changes with certain prenatal factors have altered the epidemiology of this patient population. First, there has been a tremendous progress in fetal diagnosis of congenital malformations with concordant increase in the rate of termination of pregnancy for fetal anomaly (TOPFA) in the last 2 decades.[13,14] Second, some studies have shown that prenatal folic acid and other multivitamin supplementation significantly decreased the birth prevalence of some congenital malformations.[15,16] We hypothesized that the above factors have altered prevalence of CA in the CHD population. The purpose of our study was therefore to provide up-to-date estimates of the current association between CHD and CA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All data was derived from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[17] NIS is an all-payer administrative database reporting clinical and resource use hospitalization information. We chose the NIS database instead of other databases such as the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) because NIS is the largest inpatient care database in the United States; containing approximately 8 million hospital stays each year from about 1,000 hospitals sampled to approximate a 20% stratified sample of the United States community hospitals. NIS large sample size makes it ideal for analysis of rare conditions such as specific congenital malformations. Approval for this study was obtained from both HCUP and institutional review board.

We reviewed all birth entries in the NIS database from January 1998 to December 2008 and identified all live births with CHD during birth hospitalization (case group) using CHD International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes. We also identified all live-births without CHD during the same period (control group). Twenty-three CA diagnoses and 10 CHD diagnoses were selected for analysis. We compared the prevalence of these 23 selected CA diagnoses in the case and control group. Longitudinal analysis was performed to determine temporal variation of CA prevalence in the CHD population during the study period.

We only included diagnoses made either clinically during birth hospitalization or by autopsy for live births that died during birth hospitalization. In order to avoid double counting, we restricted our inclusion criteria to diagnoses made during birth hospitalization. We ensured this by including only hospitalizations with ICD-9 code for normal and complicated delivery (650.0-669.0); hence, excluding diagnoses made during inter-hospital transfer or readmission hospitalization. In patients with multiple congenital malformations, each malformation was counted separately. We grouped all CA into different organ-systems. Based on the classification system used by Christensen et al.,[18] we defined multiple organ system involvement as live births with non-cardiac CA involving two or more organ-systems.

Data weighting was performed with Statistical Analytical Software (SAS) in accordance with HCUP recommendations.[19] The NIS has undergone some changes over time in terms of sampling strategy, weighting strategy, and data element available. We adjusted for these changes in accordance with the recommendations in NIS Trend Supplemental files.[19] As per HCUP data use agreement prohibiting reporting of cell size ≤10, CHD diagnoses with cell size ≤10 were either grouped together or excluded from analysis. We used MedCalc for Windows, version 12.5 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium) to estimate odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) in order to assess strength of association of CA diagnosed in the case group relative to the control group. Time trend analysis was performed using chi-square test based on a 12-month moving average of CA prevalence calculated by dividing the number of entries of CA diagnoses in the CHD population (case group) by the total number of subjects in the case group for each 12-month period. The moving average gives a rate for all 12-month periods, thereby removing the restriction of calendar years. P-value of <0.05 was set as the cutoff for statistical significance.

RESULTS

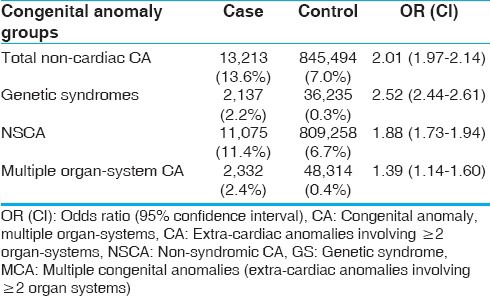

Our cohort consisted of 97,154 and 12,078,482 subjects in the case and control groups, respectively. In the CHD population (case), prevalence of non-syndromic congenital anomaly (NSCA), GS, and overall extra-cardiac congenital anomaly (CA) were 11.4, 2.2, and 13.6%, respectively. In the control group, prevalence of NSCA, GS, and CA were 6.7, 0.3, and 7.0%, respectively. NSCA (OR: 1.88, CI: 1.73-1.94), GS (OR 2.52, CI 2.44-2.61), and overall CA (OR: 2.01, CI: 1.97-2.14) were strongly associated with CHD [Table 1].

Table 1.

Prevalence of congenital anomalies in CHD population

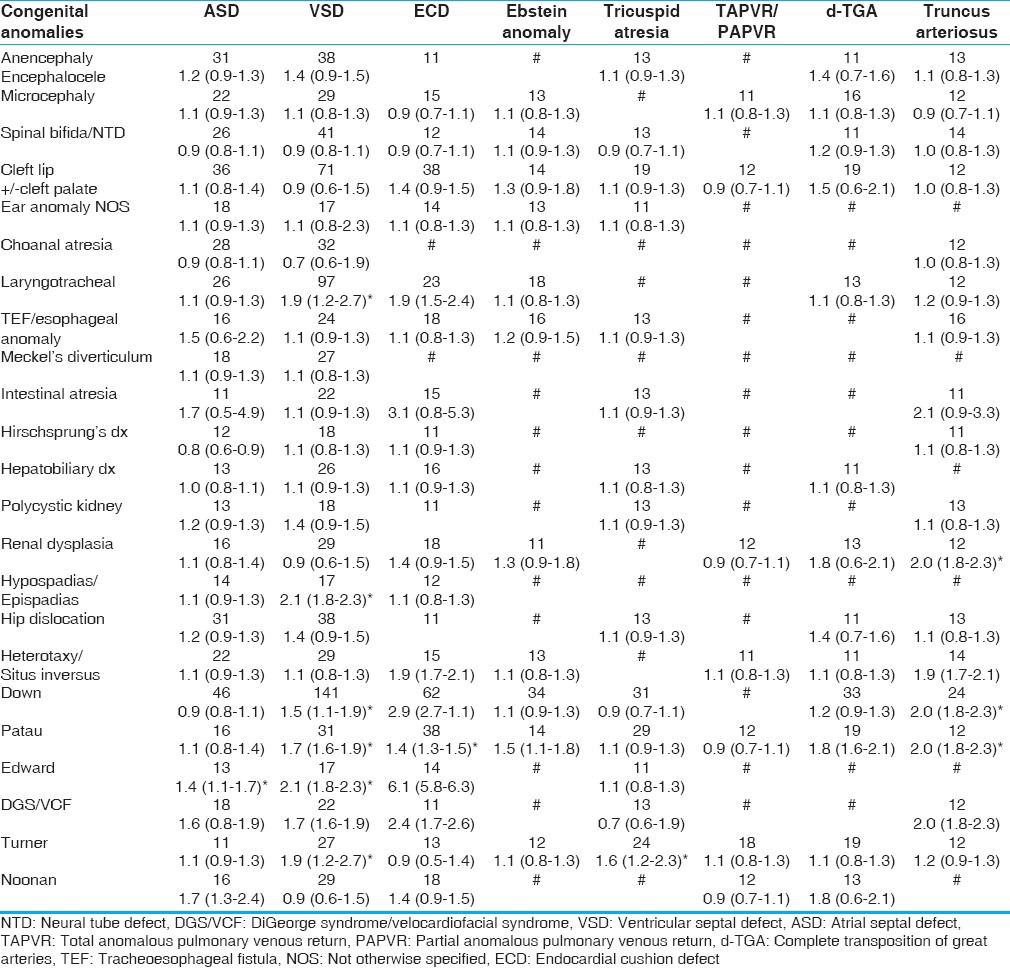

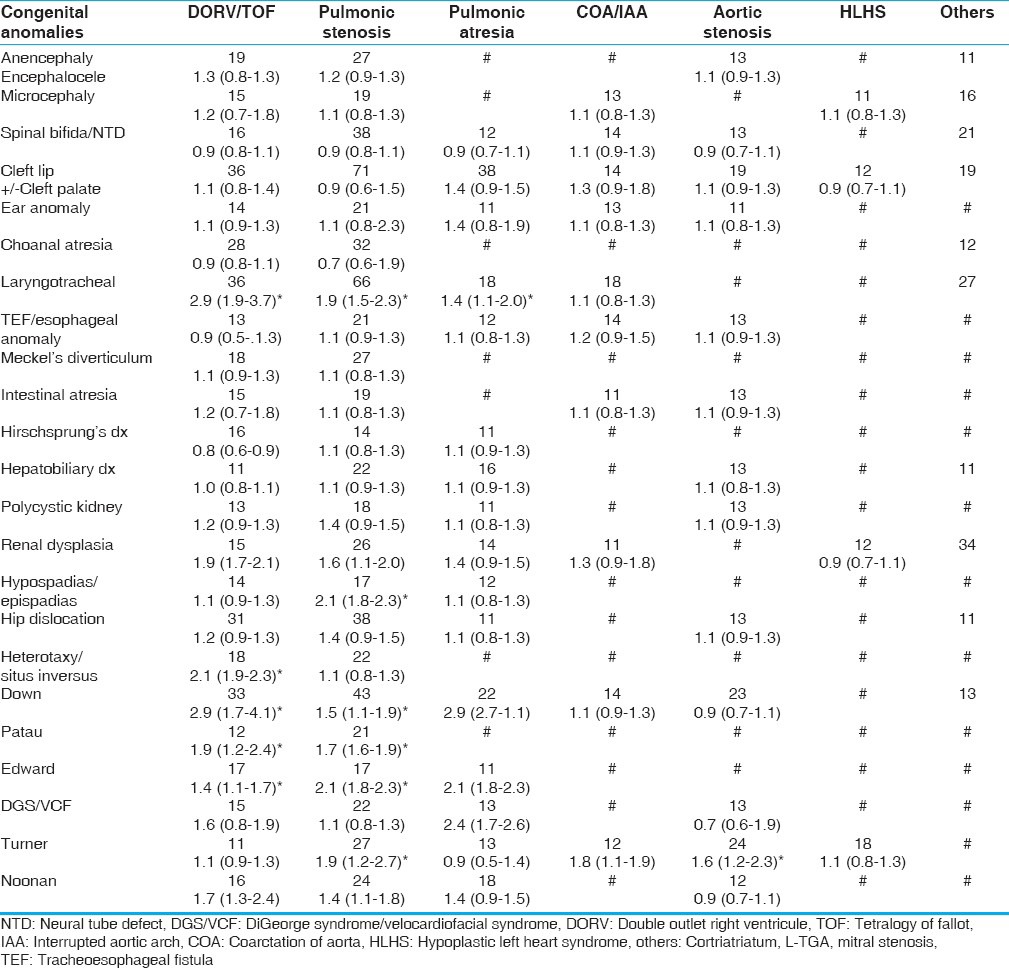

When we analyzed specific CA diagnosis, our study showed that laryngo-tracheal anomaly was associated with ventricular septal defect (VSD;OR 1.9; CI 1.2-2.7), endocardial cushion defect(ECD;OR 1.9, CI 1.5-2.4), double outlet right ventricle/tetralogy of fallot (DORV/TOF; OR 2.9, CI 1.9-3.7), and pulmonary atresia (OR 1.4, CI 1.1-2.9). Hypospadias/epispadias was associated with VSD (OR 2.1, CI 1.8-2.3) and pulmonic stenosis (OR 2.6; CI 1.8-3.3). Renal dysplasia was associated with DORV/TOF (OR 1.9, CI 1.7-2.1) and pulmonic stenosis (OR 1.6, CI 1.1-2.0). Heterotaxy/situs inversus is associated with ECD (OR 1.9, CI 1.7-2.1), truncus arteriosus (OR 2.1, CI 1.8-2.3), and DORV/TOF (OR 2.1, CI 1.8-2.3). GSs were strongly associated with most CHD diagnoses [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Prevalence of anomalies in CHD population

Table 3.

Prevalence of anomalies in CHD population

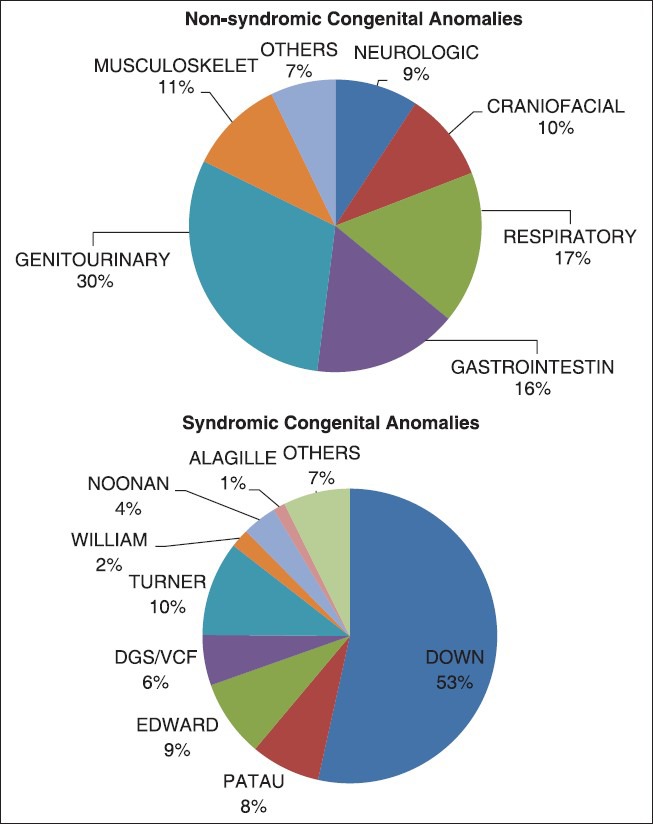

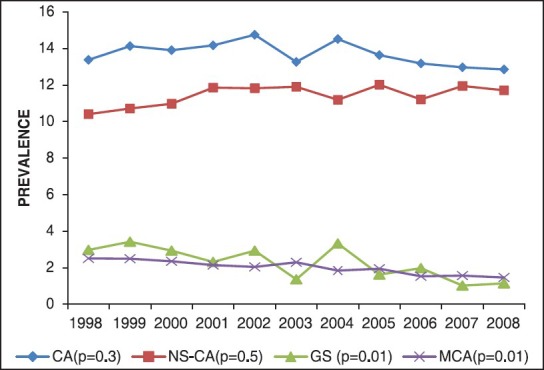

Figure 1 shows relative distribution of syndromic and NSCA in our CHD population. Figure 2 shows time trend analysis of CA prevalence in the case group over the 11-year study period. Prevalence of GSs (P = 0.01) and multiple congenital anomalies (P = 0.01) decreased significantly over the study period.

Figure 1.

Distribution of congenital anomalies

Figure 2.

Time trend analysis of congenital anomalies prevalence

DISCUSSION

Published studies suggest association between CHD and certain extra-cardiac congenital anomalies.[4,5,11,12,20,21,22,23,24,25] Evidence in support of such association is stronger for syndromic malformations compared to non-syndromic malformations.[2,11,20,25] Although there are several studies that have looked at association between certain CHD diagnoses and selected extra-cardiac CA, there is paucity of population-based studies focusing on comprehensive evaluation of association between all major CHD and all major extra-cardiac CAs. Part of the reason for this is because of the low prevalence of some CAs making it very difficult to obtain sample population powered enough to analyze such associations. The purpose of our study was therefore to perform a comprehensive analysis of association of all major CA based on a large representative sample population powered to detect any significant difference.

Our data showed that newborns with CHD frequently have associated extra-cardiac CA. This association is true for both syndromic malformation (OR 2.52, CI 2.44-2.61) and NSCA (OR: 1.88, CI: 1.73-1.98). Craniofacial, respiratory, and genitourinary malformations were associated with CHD in our cohort. Situs inversus was also associated with CHD diagnosis specifically with endocardial cushion defect and pulmonary valve disease. Our results were consistent with prior studies,[4,5,12,25,26] which showed similar associations. However, contrary to some published data,[22,23,24] we did not find any association between CHD diagnosis and gastrointestinal and limb anomalies. The reason for this discrepant finding is not apparent. It is possible that certain gastrointestinal abnormalities like malrotation and biliary atresia may be diagnosed later and not at the birth admission. However, we believe that our result is more applicable to the general population because our estimates were based on large representative population.

Consistent with prior studies,[4,5,11] GSs were strongly associated with CHD diagnoses and this association was most significant with septal defects, endocardial cushion defect, pulmonary valve disease, tricuspid valve disease, aortic valve disease, truncus arteriosus, and aortic arch anomalies. This finding may be as a result of common underlying etiology because CHD is a known phenotypic manifestation of most of the GSs included in our study.

Although prevalence of extra-cardiac CA did not change in the CHD population, prevalence of GSs and multiple organ-system CA decreased significantly during the study period. We believe that this change could be as a result of modification of prenatal factors such as TOPFA and prenatal vitamin supplementation. However, our study was not designed to establish direct causality.

This study has some limitations. It is a retrospective review of entries from a de-identified administrative database. Second, there is always the risk of ‘double counting’ when using data from a de-identified database. We circumvented this problem by including only cases of diagnosed made during the birth hospitalization. Our study population comprised of neonates only, and as a result we could have missed diagnoses that presented after birth hospitalization. However, since we used the same inclusion criteria (diagnosis during birth hospitalization) for our case and control group and as a result; any underestimation caused by our restrictive inclusion criteria should not affect our measure of association.

CONCLUSION

This is the largest and most comprehensive population-based study evaluating association between CHD and CA in newborns. Our data also showed significant decrease in prevalence of syndromic malformations and multiple organ-system CA in the CHD population, while prevalence of overall extra-cardiac CA remained unchanged.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the NIS, HCUP, and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for granting us unlimited access to their database. We also thank Jen Yau and Ugochi Egbe for their contribution during data mining, formatting, statistical analysis, and proofreading. There are no relevant financial interests, affiliations, or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee K, Khoshnood B, Chen L, Wall SN, Cromie WJ, Mittendorf RL. Infant mortality from congenital malformations in the United States, 1970-1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:620–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tennstedt C, Chaoui R, Korner H, Dietel M. Spectrum of congenital heart defects and extracardiac malformations associated with chromosomal abnormalities: Results of a seven year necropsy study. Heart. 1999;82:34–9. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman JI, Christianson R. Congenital heart disease in a cohort of 19,502 births with long-term follow-up. Am J Cardiol. 1978;42:641–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(78)90635-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferencz C, Rubin JD, McCarter RJ, Boughman JA, Wilson PD, Brenner JI, et al. Cardiac and noncardiac malformations: Observations in a population-based study. Teratology. 1987;35:367–78. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420350311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenwood RD. Cardiovascular malformations associated with extracardiac anomalies and malformation syndromes. Patterns for diagnosis. Clin Pediatr. 1984;23:145–51. doi: 10.1177/000992288402300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferencz C, Boughman JA, Neill CA, Brenner JI, Perry LW. Congenital cardiovascular malformations: Questions on inheritance. Baltimore-Washington Infant Study Group. J AmColl Cardiol. 1989;14:756–63. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg KA, Astemborski JA, Boughman JA, Ferencz C. Congenital cardiovascular malformations in twins and triplets from a population-based study. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:1461–3. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150240083023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickinson DF, Arnold R, Wilkinson JL. Congenital heart disease among 160 480 liveborn children in Liverpool 1960 to 1969. Implications for surgical treatment. Br Heart J. 1981;46:55–62. doi: 10.1136/hrt.46.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman JI. Natural history of congenital heart disease. Problems in its assessment with special reference to ventricular septal defects. Circulation. 1968;37:97–125. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.37.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francannet C, Lancaster PA, Pradat P, Cocchi G, Stoll C. The epidemiology of three serious cardiac defects. A joint study between five centres. Eur J Epidemiol. 1993;9:607–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00211434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferencz C. Origin of congenital heart disease: Reflections on Maude Abbott's work. Can J Cardiol. 1989;5:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kallen B, Eduardo CE. A modified method for the epidemiological analysis of registry data on infants with multiple malformations. Int J Epiderm. 1999;28:701–10. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cragan JD, Khoury MJ. Effect of prenatal diagnosis on epidemiologic studies of birth defects. Epidemiology. 2000;11:695–9. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200011000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khoshnood B, De Vigan C, Vodovar V, Goujard J, Lhomme A, Bonnet D, et al. Trends in prenatal diagnosis, pregnancy termination, and perinatal mortality of newborns with congenital heart disease in France, 1983-2000: A population-based evaluation. Pediatrics. 2005;115:95–101. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czeizel AE. The primary prevention of birth defects: Multivitamins or folic acid? Int J Med Sci. 2004;1:50–61. doi: 10.7150/ijms.1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Botto LD, Olney RS, Erickson JD. Vitamin supplements and the risk for congenital anomalies other than neural tube defects. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2004;125C:12–21. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 1998-2008. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality R, MD. [Last access on 2013 Oct 22]. Available from: //www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp .

- 18.Christensen N, Andersen H, Garne E, Wellesley D, Addor MC, Haeusler M, et al. Atrioventricular septal defects among infants in Europe: A population-based study of prevalence, associated anomalies, and survival. Cardiol Young. 2013;23:560–7. doi: 10.1017/S1047951112001400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Trends Supplemental Files. 1998-2008. [Last accessed on 2013 Sept 28]. Available from: //www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nistrends.jsp .

- 20.Carmi R, Boughman JA, Ferencz C. Endocardial cushion defect: Further studies of “isolated” versus “syndromic” occurrence. Am J Med Genet. 1992;43:569–75. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320430313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.David TJ, O’Callaghan SE. Cardiovascular malformations and oesophageal atresia. Br Heart J. 1974;36:559–65. doi: 10.1136/hrt.36.6.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.German JC, Mahour GH, Woolley MM. Esophageal atresia and associated anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1976;11:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(76)80182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glauser TA, Rorke LB, Weinberg PM, Clancy RR. Congenital brain anomalies associated with the hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatrics. 1990;85:984–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PD, Bigger JT, Weinberg D, Malm JR. Use of diphenylhydantoin in ventricular arrhythmias following open heart surgery. Surg Forum. 1966;17:185–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kallen B, Winberg J. A Swedish register of congenital malformations. Experience with continuous registration during 2 years with special reference to multiple malformations. Pediatrics. 1968;41:765–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ivemark BI. Implications of agenesis of the spleen on the pathogenesis of conotruncus anomalies in childhood; an analysis of the heart malformations in the splenic agenesis syndrome, with fourteen new cases. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1955;44:7–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]