ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

With the reorganization of primary care into Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT) teams, the Veteran Affairs Health System (VA) aims to ensure all patients receive care based on patient-centered medical home (PCMH) principles. However, some patients receive the preponderance of care from specialty rather than primary care clinics because of the special nature of their clinical conditions. We examined seven VA (HIV) clinics as a model to test the extent to which such patients receive PCMH-principled care.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the extent to which HIV specialty care in VA conforms to PCMH principles.

DESIGN

Qualitative study.

PARTICIPANTS

Forty-one HIV providers from seven HIV clinics and 20 patients from four of these clinics.

APPROACH

We conducted semi-structured interviews with HIV clinic providers and patients about care practices and adherence to PCMH principles. Using an iterative approach, data was analyzed using both a content analysis and an a priori, PCMH-principled coding strategy.

KEY RESULTS

Patients with HIV receive varying levels of PCMH-principled care across a range of VA HIV clinic structures. The more PCMH-principled HIV clinics largely functioned as PCMHs; patients received integrated, coordinated, comprehensive primary care within a dedicated HIV clinic. In contrast, some clinics were unable to meet the criteria of being a patient’s medical home, and instead functioned primarily as a place to receive HIV-related services with limited care coordination. Patients from the less PCMH-principled clinics reported less satisfaction with their care.

CONCLUSIONS

Even in a large, integrated healthcare system, there is wide variation in patients’ receipt of PCMH-principled care in specialty care settings. In order to meet the goal of having all patients receiving PCMH-principled care, there needs to be careful consideration of where primary and specialty care services are delivered and coordinated. The best mechanisms for ensuring that patients with complex medical conditions receive PCMH-principled care may need to be tailored to different specialty care contexts.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2677-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: patient-centered medical home, specialty care, HIV, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

In 2010, the Veteran Affairs Health System (VA) launched a nationwide initiative, transforming primary care into a model of care known as Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT),1 based on the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH),2 a promising reorganization of care.3 PACT is premised on seven principles, specifying that care be: patient-driven, team-based, efficient, comprehensive, continuous, and emphasize good communication and coordination. These elements have been tailored to primary care, where the VA has focused PACT initiatives.

Many patients, however, receive substantial portions of their care from specialists.4,5 There is debate as to how specialty care services relate to PACT, whether these clinics should act as PACTs, and questions about the configuration of care coordination between specialty care and PACT primary care clinics.6–8 Ryan White Clinics, federally funded (HIV) programs, have taken on the role of the patient-centered medical home,9,10 and perform well on some measures of patient-centeredness, such as access, quality and coordination.11 Therefore, how the PACT model is best applied to patients with HIV is not clear.

HIV clinics have historically provided integrated, multidisciplinary care, because of the complexity of patient management and dominance of HIV-related issues. When the HIV/(AIDS) epidemic began, providers in comprehensive teams focused on slowing the disease, managing difficult, HIV-associated infections, and helping patients have the best possible quality of life as they developed AIDS and eventually died. As effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) emerged, these dedicated providers helped patients manage stigma and cope with complex medication regimens, with frequent therapy adjustments in response to virological failure, emergence of antiretroviral resistance, medication intolerance and drug toxicities. Now, with refinement of more effective, better tolerated, less toxic ART,12 HIV has a better prognosis and been transformed into a chronic condition in which comorbidity management is central.13,14 This is especially the case as HIV-infected patients age; 64 % of Veterans with HIV in VA are over age 50 and increasingly have aging-associated comorbidities,15 most commonly depression (51 %), hypertension (49 %), dyslipidemias (43 %), substance abuse (30 %) and diabetes (19 %).16 Thus, care for these patients has become more about comorbidity than HIV management.17–19

In VA, patients with HIV receive substantial care from specialists, either alone or in conjunction with primary care.20 As it is a VA goal to have all patients receiving PACT-principled care, understanding how the care patients with HIV receive aligns with PACT principles is critical. Therefore, we sought to understand the extent to which HIV care received by Veterans from VA specialty care conforms to the hallmarks of PACT.

METHODS

We conducted a qualitative study to understand provider and patient perceptions of VA HIV clinic care, and then examined the extent to which those perceptions aligned with PACT principles. We conducted semi-structured interviews with HIV clinic providers and staff at seven VA medical centers (VA), located in the northeast, west coast, south and south central US, and with patients at four of these clinics (see Table 1). Clinics ranged from large, dedicated HIV clinics, to smaller infectious disease clinics with an HIV specialist, to low patient volume clinics. These clinics were a convenience sample of sites participating in an HIV testing study.21

Table 1.

Clinic Characteristics and Staff Interviewed at Each Site

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 | Site 6 | Site 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facility size | Large | Large | Small | Large | Large | Medium-Large | Large |

| US geographic region | West Coast | West Coast | West Coast | Northeast | South Central | South | Northeast |

| Urban/rural | Urban | Suburban | Urban | Urban | Urban | Rural | Urban |

| Patient-panel size | N = 620 | N = 120 | N = 75 | N = 160 | N = 150 | N = 240 | N = 450 |

| Clinic staff interviewed* | |||||||

| Dedicated infectious disease clerk | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Licensed vocational nurse | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Medical doctor (including Fellows) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Nurse practitioner | 1 | ||||||

| Pharmacist | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Physician’s assistant | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Psychologist | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Psychiatrist | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Registered nurse | 1 | ||||||

| Social worker | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Total | 10 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

*Interviewees are representative of the majority of providers available in clinic

We interviewed clinic staff, including physicians, physician assistants, nurses, social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, pharmacists and clerks. We sought to interview all staff in the clinic. Staff were identified by their clinic role, recruited through email and telephone calls, and interviewed over the phone or in person by study staff, experienced in qualitative interviewing. Provider interviews covered clinic care practices and how care related to PACT principles (see online Appendix 1). We asked about HIV clinic roles, processes, familiarity with PACT initiatives, and which aspects of PACT they currently saw happening in their clinic.

Patients from four sites were recruited through the HIV clinics. We sought to interview 20 patients, at which point saturation is often achieved.22 Interested patients received patient information brochures detailing the project and were directed to the Research Assistant (RA) in the HIV clinic. Patients were interviewed in a private room, before or after their appointment. Patient interviews covered: experiences with the HIV clinic, relationship with provider, appointment flow, and the types of services they received through the clinic (see online Appendix 1). We also asked about PACT principles, using lay language to ascertain the patients’ experiences.

For each interview, the interviewer wrote descriptive, systematic fieldnotes,23 including detailed responses to interview questions and verbatim passages, in a unique Microsoft Word document containing the interview questions. Interviews took place between 2010 and 2011. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Providers were not compensated, per VA guidelines; patients received $20 VA vouchers. Study procedures were approved by VA institutional review boards (IRBs).

ANALYSIS

We conducted a multi-phased content analysis, beginning with open coding of staff interviews and then applying a priori categories based on the seven PACT principles.24

First, two coders (BB & GF) reviewed interview fieldnotes to develop a broad set of content codes to explore the range of care practices. We identified key content areas regarding clinic activities, the roles of HIV providers, and the extent to which they perceived the clinic to provide care consistent with PACT principles. Through this process, we identified 35 dimensions relevant to clinic care (see online Appendix 2).

We then sorted the data into the 35 dimensions according to site, using Microsoft Excel.25 Each interview fieldnote was reviewed (by GF, BB, HS); relevant passages were captured in the appropriate dimension and entered into the corresponding cells. A clinic summary was created for each site, which included a summary of clinic perceptions along each of the 35 dimensions, thereby providing a synopsis for each site, representing the range of provider experiences.

Next, we determined how the clinics mapped to the PACT-principles. Based on PACT and PCMH literature, we operationalized the PACT principles before applying them to the HIV clinics.26,27 Definitions (Table 2) were tailored to HIV specialty care, relevance to care of Veterans with HIV, and ascertainable from the interviews. We then applied these operationalized constructs to the coded fieldnotes to assess the extent to which each site’s practice reflected each PACT-principle.

Table 2.

PACT Principle Definitions, Operationalized for HIV Clinics, and What Meets Criteria for High, Medium, or Low

| VA definition | High | Medium | Low | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient- driven | Focus on person not condition. Support for decision making. Access to face-to-face and/or virtual care. |

Focus on all patients’ needs, including mental health, SUD, primary healthcare. | Programs are available through referral, some care coordination available. | Only HIV-specific needs are met. |

| Team-based | Interdisciplinary team: PCP, RN, care manager, admin staff, specialists and other needed clinical services. | Presence of interdisciplinary team in clinic or designated profs. | Interdisciplinary team members available. | Interdisciplinary services only through referral. |

| Efficient | Technology maximizes efficiency. Right professional at the right time (emphasizes PCP as core). Practice at top of license. |

Uses secure electronic messaging, tele-medicine and a clinical case registry. All team members contribute to care (i.e., even low-level team members do significant work). |

Some technology &/or Variation in level of contribution by role (i.e., clerk only makes appointments.). | No technology. All care provided by primary provider. |

| Comprehensive | Whole person oriented care (emphasizes PCP as core). Meets all medical, behavioral, psychosocial and functional status issues. Use of health coaching education consultation, screening, preventive care services. Patient in life context. |

Team focused on addressing social and contextual needs of patients. Offered services like support groups. HIV clinic as primary care. |

Team recognizes need to address MH and social/contextual issues. HIV clinic as primary care. |

Referred out for MH if seemed to be problematic. Saw psychosocial needs as beyond purview of HIV clinic care. HIV clinic not primary care. |

| Continuous | Continuous, longitudinal relationship between patient and PCP. Arranging care with qualified professionals, as needed. |

Same provider seen each time. HIV provider as PCP. |

Patient sees same provider most visits, but not viewed as PCP. | Patient does not see same provider each visit. High fellow rotation. |

| Communication | Patient-centered patient-provider communication. Good team communication that remains patient-focused. |

Regular team meetings. Environment conducive to open communication. |

Some communication mechanisms, not formal. Need for communication not addressed. |

Communication seen as happening through EMR only. Little team focus, little active team communication. |

| Coordinated | Care is coordinated across the healthcare system and outside of the HIV clinic, in part, through the use of technologies (electronic patient tracking registries, IT, health information exchange). | Established relationships and good communication with other specialties. Facilitates referral. Uses patient registry to track patients, ensure visit follow-up. Using electronic clinical reminders to address comorbidities. |

Refers outside HIV clinic through EMR. Some use of electronic tracking. |

Problems linking patients to care outside clinic. No discussion of use of registry, clinical reminders. Uses EMR to document only. |

PCP primary care provider; RN registered nurse; EMR electronic medical records; IT information technology; MH mental health; SUD substance use disorder

We reviewed the operationalized PACT definitions and determined what would constitute “high,” “medium,” or “low” adherence to each PACT-principle. Sites were considered “high,” if they met the PACT-principle; and “low” if they did not meet the criteria. “Medium” was reserved for sites partially meeting the principle. Each clinic summary was reviewed, and then compared to the criteria for each PACT definition. We worked iteratively, comparing clinic synopses, to determine the extent to which HIV clinic practices reflected PACT principles.

Patient interviews were coded by two investigators (BB & GF) to understand the extent to which they experienced PACT-principled care. These data were compared to the staff interview findings and used to further explore how PACT principles were enacted in the HIV clinics. Any analysis disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached.

RESULTS

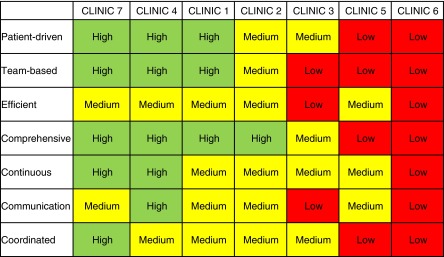

We interviewed 41 providers from seven HIV clinics, and found that the organization of HIV specialty care varied substantially by site and identified a range of ways HIV clinics provide care. Based on these interviews, we organized clinics summaries from sites whose practices most closely reflected PACT-principled care to those where these elements were difficult to achieve (see Table 3). Additional patient interviews were conducted at a convenience sample of four clinics (1–4), which turned out to be in the middle of this PACT distribution. These patients described diverse care experiences, reflecting PACT principles to varying extent.

Table 3.

High, Medium, Low Alignment with PACT Principles, Arranged from Most to Least PACT-Principled*

In the three larger, urban facilities (Clinics 1, 4, 7), patients received patient-driven, team-based, comprehensive primary care within a dedicated HIV clinic—closely mirroring PACT-principled care. These clinics were interdisciplinary with coordinated mental health, social work, pharmacy and psychiatry. They had multiple team members, many of whom were integrated into the clinic, had formal or informal communication for team-based care, and most had continuity of providers. These sites were noted to be highly or moderately able to adhere to the PACT principles. These sites also viewed themselves as primary care: “It’s made explicit to primary care that patients in the HIV clinic are getting their primary care here,” (Doctor of Medicine [MD] 4:1). (Participants are identified by: Role, Clinic#:Participant#.) The pharmacist emphasized Clinic 4 was better for their patients, because, “Even primary care doesn’t give the supportive care we have here.” Patients concurred: “I was going to be assigned a PCP [primary care provider] but why?” I already see [the doctor] once a month, so it made more sense to see him. He agreed.

In contrast, three clinics (3, 5, 6) only provided HIV-related care, often with staff limited to an HIV specialist and nurse; these clinics did not provide primary care services. All other clinical care, including mental health, was referred out to other services, although often with coordination problems. Care was not patient-driven; communication was poor. The care at these HIV clinics did not reflect PACT-principled care. These sites did not view themselves as primary care, emphasizing, “We are their HIV doctors, we are not their primary care doctors,” and “if you don’t practice primary care every day, you’re not going to be good at it anyway,” (MD 5:2).

Findings from the patient and provider interviews were consistent. Patients at sites exhibiting more PACT-principled care described closer relationships with their providers and considered the HIV clinic as their primary care, whereas patients at sites exhibiting fewer PACT principles described poor communication, and receipt of HIV services only.

Patients who received care from both the HIV and primary care clinic described problems: “Doctors I’ve seen for primary care say, ‘Oh, your [HIV] doctor will need to take care of that.’ At [the HIV clinic], ‘Oh, your primary care doctor should have done that.’ Then back to primary care when I need a non-[HIV] service. … I hear other patients talking about this problem sometimes,” (Patient 2:1). Several patients wanted to receive more primary care services through the HIV clinic, in part because of perceived stigma.

HIV Clinic as PACT

Notably, at the time of the interviews in 2010–2011, few HIV providers had heard about VA’s PACT initiative, and instead learned about it from our interviewer. Some were, however, familiar with PCMH. Several of the more PACT-principled clinics felt they were already functioning as PACTs. When told about PACT, an MD (7:3) responded, “We’re doing this already!” with a psychologist (4:1) noting they had provided “integrated, interdisciplinary care since 1997.” An MD (1:1) further stated: “the teamlet concept is an adaptation of what we’re doing now,” and went on to discuss how their providers worked in slightly larger versions of teamlets. After enumerating the PACT-like services they offered, a psychiatrist (1:1) added: “I really can’t think of anything we are not doing.”

Below, we describe how different sites’ practices reflected each PACT principle.

Patient-Driven

At the highly patient-driven sites, providers spoke of close relationships with their patients: “Our biggest strength is that we know our patients very well and there’s a lot of trust,” (MD 7:2); and patients spoke highly of the relationships with their providers: “We talk about everything, from my condition, to my health at the moment, my friends, money, everything, there’s no shame!” (Patient 1:2).

These relationships were in contrast to Clinic 5 providers who did not have their own patient panels, likely undermining patient–provider relationships. Both a provider and patient lamented lacking a social worker to help with, “paperwork, housing, and employment.”

Access was problematic at several clinics offering weekly, half-day clinics. One provider noted this did not meet the needs of geographically dispersed patients with complex needs who received inadequate appointment times. Not having access to an HIV provider outside clinic hours was problematic for patients, “I’ve had some bad experiences because I’m ‘ID’ [infectious disease]—no one will do anything because I’m ID. Why should I have to wait until ID day; four times I had to wait—they won’t talk to me or they keep peeking out to see if I left—shame on them and shame on ID doctors not being available,” (Patient 2:2).

Team-Based

A provider at Clinic 4, a highly team-based site, described their care as a “ubiquity model,” where patients saw all of the providers. This was seen as particularly beneficial because it destigmatized mental health, due to everyone’s familiarity with the mental health providers. Patients liked being able to see an HIV clinic psychiatrist, and noted the range of professionals seen at an appointment. In contrast, sites that were low in their abilities to provide team-based care described lacking psychologists, social workers and pharmacists. Two sites had RNs reassigned to primary care PACTs. A physician’s assistant (PA) (3:1) noted: “Not all the staff gets along,” with MD (3:1) adding: “The strength of our clinic is the staff’s great expertise.” Here, providers functioned as independent experts, working in parallel instead of together as a team, contributing to “low” team-based care.

Efficient

None of the clinics met all the criteria for efficiency. Some clinics maximized technology use; others had appropriate professionals practicing at the top of their license (i.e. optimizing their skills); no clinic did both. Clinic 5 discussed technologies, such as tracking patients through the VA clinical case registry and a provider who taught patients about My HealtheVet, VA’s online personal health record. Clinic 2 used telehealth technologies to reach rural patients.

Efficient use of clinic staff was evident at several sites, where providers made significant contributions to clinic functioning. For example: one PA saw walk-ins during non-clinic hours, or provided urgent care; an organized clerk was seen as keeping the clinic “on track”; a nurse functioned as the care coordinator for their “teamlet”; a social worker organized extensive social activities.

Comprehensive

The highly comprehensive sites provided a range of services. A Clinic 7 provider noted they offered everything but palliative care. A pharmacist (4:1) commented: “even primary care doesn’t give the supportive care we have here.” Patients at these sites enjoyed being able to receive considerable care through the HIV clinic, “I really trust [my doctor]… We talk about everything really—prevention, nutrition, sometimes blood pressure, losing weight. It’s comfortable, I can talk to her about anything, really,” (Patient 1:1). Providers at sites that did not provide comprehensive care noted, “whole person orientation wouldn’t work,” because it was “impossible to provide all that care,” and that, “we only deal with their HIV-related issues,”(MD 5:1); an NP (5:1) similarly responded: “we are not their primary care providers, but we refer and coordinate their care, we just don’t have enough space and personnel for this.”

Continuous

At sites that achieved continuous care, providers had their own patient panels, and fostered long-term relationships. An MD (2:1) noted: “It’s important for our patients to know ‘that’s my doctor.’” Providers without their own panel noted it was “challenging to have an ongoing personal relationship with patients when we’re constantly rotating,” (MD 3:2). It was also challenging for some sites to maintain panels: “We try to follow the same patients that we’ve seen before, but this doesn’t regularly happen,” MD 6:3, with another MD 6:1 adding, “You know, it gets chaotic when you take vacations so it’s better this way… patients just see whatever provider is available.” The lack of continuity was problematic for patients: “I’ve seen five different residents within the last 2 and a half years. It’s hard to open up about these private issues to these strangers,” (Patient 3:4).

Communication

At sites with good communication, such as Clinic 1, providers sometimes saw patients together, with the mental health provider acting as the “ombudsman,” facilitating patient–provider interactions. Another Clinic 1 provider described their interactions as “organic,” attributing this to the small clinic space. In addition to their informal communication, there were also twice weekly, formal meetings. Sites with poor communication generally had no formal meetings: “We never really all meet together, but one-on-one when needed,” (MD 3:2). The licensed vocational nurse (LVN) (3:1) added: “We don’t talk that much and we don’t have meetings to discuss patients.” These limited interactions may have stemmed from poor working relationships, as this LVN also stated: “I can’t have team huddles with [the PA], she’s just so busy. She just kind of barks orders at me and just wants things from me and I don’t like working with her, she’s not very friendly.” Patients at these sites were not confident in the communication among providers, and speculated that perhaps they communicated through their electronic medical record. “I’m not sure if the doctors communicate to each other about what’s going on with me. I always have to help them catch up with what’s been going on in other parts of the VA,” (Patient 2:2).

Sites with poor provider–provider communication also had poor patient–provider communication “There have been several times when I thought he wasn’t really listening to me. Almost like he’s just going through the motions of what he has to do in the clinic, but not really [being] present with me,” (Patient 3:4).

Coordinated

Highly coordinated sites offered many in-clinic services, but when care coordination was needed, they had good relationships with other services, “I like that our clinic has a good connection to subspecialty care like gastrointestinal (GI) and mental health,” (MD 7:3). A Clinic 4 patient noted that his provider walked him to Social Work and another described his HIV provider visiting him when he was admitted for a heart attack, and “fixed things up,” by acting as an advocate. In contrast, MD (6:2) noted: “it takes a long time for our patients to be seen by other referred services [mental health, social work], and this is just unacceptable.” A coworker added that coordination is important, but lacking and chaotic: “We’re supposed to alert each other [using the electronic health record or telephone] on important things we do with the patients [like] new medications, but this isn’t systematically done with all providers,” (MD 6:1). A Clinic 2 patient described the relationship between the HIV clinic providers and primary care as a “battle.”

Discussion

The patient-centered medical home concept has gained increasing influence over the recent period of health reform, though studies remain mixed as to effects on quality and outcomes.3,28,29 What is even less clear, however, is how these principles apply to the care of patients with a dominant condition most commonly cared for in specialist clinics. We found wide variation in the ways in which seven HIV Specialty Care Clinics provided care consistent with the PACT-principles, even in the context of a concurrent large investment in primary care medical homes. Some were able to achieve many of the hallmarks of patient-centered care, while others instead functioned primarily as a place to receive subspecialty services.

Patients’ perceptions of care aligned with the extent to which clinics were PACT-principled. Patients who received care in PACT-principled clinics valued the comprehensive care and viewed the clinics as their medical home. In contrast, patients at less PACT-principled clinics complained about limited clinic hours, problematic care coordination, and perceived stigmatization. This could be due to the small number of patients interviewed at each site, but is nevertheless provocative, suggesting possible advantages for a medical home tailored to the needs of this specialty-oriented population.

We thus identified two diverging models in the provision of PACT-principled care in HIV specialty clinics. Clinics adhering to the first model effectively functioned as PACTs, likely having enculturated PACT principles years earlier in the response to observed needs created by the HIV epidemic, and exemplified providing the essential components of effective HIV care.10 Not surprisingly, these providers viewed their care as PACT-principled. Ironically, two of the more PACT-like HIV clinics in the study actually lost nurses—who were critical to the PACT-like approaches that had evolved in these clinics—during the staffing shifts that came about to support institution of the Primary Care PACTs. Although there is no way to assess the net effect of this nursing change on Veterans’ outpatient care overall, the loss of nursing staff may have made team-based, comprehensive care more difficult in these HIV clinics.

Highly PACT-principled HIV clinics may have lessons for both primary care and specialty clinics trying to implement PACT-principled care. First, team work and effective patient–provider and provider–provider communication greatly enhanced the care environment. Second, robust staffing was key to meeting all patients’ needs. Finally, capitalizing on VA technologies led to more efficient care.

The second care model followed the traditional specialist consultation structure. Patients and providers at these clinics viewed these clinics as providing HIV specialty care only; the clinics sought to maintain that role. However, many of the patients did not seem to have an appropriate medical home, underscoring the importance of delineating the relationships between medical homes and their neighbors.30 Patients described problems receiving care outside HIV clinic hours, experienced stigmatization, and may not receive all needed services. These clinics were not team-based, had less communication, and struggled to provide patient-driven, coordinated care—the latter two were especially problematic for rural patients.

Successful application of this second “traditional” model may be possible, but our results suggest that there is a need for greater coordination with primary care PACTs. Resources to coordinate and link HIV specialists and their patients with primary-care––based PACTs are particularly necessary, and would constitute an essential element for creating a truly manageable medical “neighborhood” for those receiving HIV care.6,30–32 This is likely to require more than simple use of a shared medical record. The particular importance of communication and care coordination for HIV patients has been observed.33,34 Concerns about maintaining coordination have, in part, contributed to the recent US Presidential Executive Order endorsing the HIV Care Continuum Initiative as government policy for improving HIV Treatment.35

Specialty services may be the best place for some patients’ medical home.36 There are several frameworks specifying the interactions between primary and specialty care.32,37,38 The American College of Physicians notes, as we also found, that the interaction between PCMH and specialty care will not be uniform. Rather, they argue that this may vary depending on the clinical situation, physicians’ professional judgment, and patients’ needs and preferences.37,38 It may be that cases such as HIV—where specialists provide comprehensive care over extended periods for the management of complex chronic illnesses—are the ideal case for PCMH in specialty care settings, as having specialists take primary responsibility is important for patients with multimorbidities when a single disease dominates.39

So, where does the transformation to a primary-care–based PACT-principled model leave specialty care patients? There is not a one-size-fits-all solution for clinics or patients with HIV. We know that diverse and unique patient needs require tailoring to the local populations and context.40–42 Even for the most robust HIV clinics, it remains uncertain whether the best model is to change the nature of the HIV clinic so that responsible physicians have a greater emphasis on management of primary care concerns, or to transfer the patient to a primary care provider and rely on the HIV team for subspecialty care on a consultative basis. Yet we found that when the care is shared between an HIV specialty clinic and primary care, coordination was poor. Specialty clinics should consciously model themselves in accordance with their local needs, and structure themselves to optimize care coordination accordingly.

This study has limitations. Data collection occurred during the early days of PACT implementation, and may not reflect more recent changes in PACT specialty care coordination. Patient interviews did not extend to all clinics, and therefore may not have captured the full range of experiences. We were unable to collect PACT associated metrics, as these are not systematically collected for specialty care patients, which would add to our understanding of how different structures of care meet PACT goals.

Specialists have struggled to find their place in within the PCMH movement. Our findings show that even in the context of a large integrated system investing heavily in primary care medical homes, no one model predominates. Some specialties with a history of comprehensive care and difficult management problems like HIV may choose to assume full responsibility for undertaking medical home transformation, as several clinics in our study demonstrated. On the other hand, not all HIV clinics have the resources or need to become PACT-principled medical homes for their patients. In these clinics, patients may be well served with a shared model of care resulting in a medical, PACT-principled home based out of primary care and working in coordination with specialty care.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 18 kb)

Acknowledgements

Contributors

Thanks to HIV/Hepatitis QUERI members (Matthew B. Goetz, MD, and Jeffrey L. Solomon, PhD) who reviewed earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Funders

This study was funded by the Department of Veteran Affairs, Health Services Research and Development, HIV/Hepatitis QUERI. This material is based upon work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Prior Presentations

This work was presented at the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development 2012 Annual Meeting.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, Dolan ED, Maynard C, Bryson C, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid R, Fishman P, Yu O. Patient-centered medical home demonstration: A prospective, quasi-experimental before and after evaluation. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:e71–e87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, Prvu Bettger J, Kemper AR, Hasselblad V, et al. The patient-centered medical home a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):169–78. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starfield B, Chang HY, Lemke KW, Weiner JP. Ambulatory specialist use by nonhospitalized patients in us health plans: correlates and consequences. J Ambul Care Manage. 2009;32(3):216–25. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181ac9ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valderas JM, Starfield B, Forrest CB, Sibbald B, Roland M. Ambulatory care provided by office-based specialists in the United States. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(2):104–11. doi: 10.1370/afm.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinsky CA. The patient-centered medical home neighbor: A primary care physician’s view. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(1):61–2. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-1-201101040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berenson RA. Is there room for specialists in the patient-centered medical home? Chest. 2010;137(1):10–1. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bitton A. Who is on the home team? Redefining the relationship between primary and specialty care in the patient-centered medical home. Med Care. 2011;49(1):1–3. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820313e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saag MS. Ryan White: an unintentional home builder. AIDS Read. 2009;19(5):166–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallant JE, Adimora AA, Carmichael JK, Horberg M, Kitahata M, Quinlivan EB, et al. Essential Components of Effective HIV Care: A Policy Paper of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Ryan White Medical Providers Coalition. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Hirschhorn LR, Landers S, McInnes DK, Malitz F, Ding L, Joyce R, et al. Reported care quality in federal Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program supported networks of HIV/AIDS care. AIDS Care. 2009;21(6):799–807. doi: 10.1080/09540120802511992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration Durability of first ART regimen and risk factors for modification, interruption or death in HIV-positive patients starting ART in Europe and North America 2002–2009. Aids. 2013;27(5):803–13. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835cb997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene M, Justice AC, Lampiris HW, Valcour V. Management of human immunodeficiency virus infection in advanced age. JAMA. 2013;309(13):1397–405. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu C, Selwyn PA. An epidemic in evolution: the need for new models of HIV care in the chronic disease era. J Urban Health. 2011;88(3):556–66. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9552-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goulet JL, Fultz SL, Rimland D, Butt A, Gibert C, Rodriguez-Barradas M, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: do patterns of comorbidity vary by HIV status, age, and HIV severity? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(12):1593–601. doi: 10.1086/523577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.VA Public Health Strategic Healthcare Group. The State of Care for Veterans with HIV/AIDS. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2009 Report No.1-1-2009.

- 17.Kirk JB, Goetz MB. Human immunodeficiency virus in an aging population, a complication of success. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(11):2129–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vance DE, McGuinness T, Musgrove K, Orel NA, Fazeli PL. Successful aging and the epidemiology of HIV. Clin Interv Aging. 2011;6:181–92. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S14726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao H, Goetz MB. Complications of HIV infection in an ageing population: challenges in managing older patients on long-term combination antiretroviral therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(6):1210–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yano EM, Asch SM, Phillips B, Anaya H, Bowman C, Chang S, et al. Organization and management of care for military veterans with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. Mil Med. 2005;170(11):952–9. doi: 10.7205/milmed.170.11.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goetz MB, Hoang T, Knapp H, Burgess J, Fletcher MD, Gifford AL, et al. Central implementation strategies outperform local ones in improving HIV testing in veterans healthcare administration facilities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernard HR. Field Notes: How to Take Them, Code Them, Manage Them. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 3. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press; 2002. pp. 365–89. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Walnut Creek: Alta Mira; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer DZ, Avery LM. Excel as a Qualitative Data Analysis Tool. Field Methods. 2009;21(1):91–112. doi: 10.1177/1525822X08323985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein S. The Veterans Health Administration: Implementing Patient-Centered Medical Homes in the Nation’s Largest Integrated Delivery System, The Commonwealth Fund, September 2011.

- 27.Patient Centered Primary Care Implementation Work Group. Patient Centered Medical Home Model Concept Paper. Department of Veteran Affairs; 2010; Available from: www.va.gov/PrimaryCare/docs/pcmh_ConceptPaper.doc (accessed 10/9/13).

- 28.Martsolf GR, Alexander JA, Shi Y, Casalino LP, Rittenhouse DR, Scanlon DP, et al. The Patient-Centered Medical Home and Patient Experience. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(6):2273–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nutting PA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Jaen CR, Stewart EE, Stange KC. Initial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):254–60. doi: 10.1370/afm.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pham HH. Good Neighbors: How Will the Patient-Centered Medical Home Relate to the Rest of the Health-Care Delivery System? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):630–4. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1208-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stange KC, Stewart E, Jaen C. Transforming Physician Practices To Patient-Centered Medical Homes: Lessons From The National Demonstration Project. Health Aff. 2011;30(3):439–45. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colorado Health Foundation. Primary Care – Specialist Physician Collaborative Guideline., Colorado Systems of Care/Patient Centered Medical Home Initiative; 2010. Available from: http://www.cms.org/uploads/PCMH-Primary-Care-Specialty-Care-compact-(10-22-10).pdf (accessed 10/9/13)

- 33.Gifford AL, Groessl EJ. Chronic disease self-management and adherence to HIV medications. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31:S163–S6. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212153-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheid TL. Service system integration: panacea for chronic care populations? In: Kronenfeld JJ, editor. Chronic Care, Health Care Systems and Services Integration 2004. p. 141–58.

- 35.The White House- Office of the Press Secretary. Executive Order -- HIV Care Continuum Initiative. 2013 [August 28, 2013]; Available from: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/07/15/executive-order-hiv-care-continuum-initiative (accessed 10/9/13)

- 36.Casalino LP, Rittenhouse DR, Gillies RR, Shortell SM. Specialist physician practices as patient-centered medical homes. New Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1555–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1001232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laine C. Welcome to the patient-centered medical neighborhood. Ann Intern Med. 2011;2011(154):60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-1-201101040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Patient-Centered Medical Home Neighbor: The Interface of the Patient-Centered Medical Home with Specialty/Subspecialty Practices. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2010. Available from: http://www.acponline.org/advocacy/current_policy_papers/assets/pcmh_neighbors.pdf (accessed 10/18/2013)

- 39.Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition—multimorbidity. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2493–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glasgow RE, Goldstein MG, Ockene JK, Pronk NP. Translating what we have learned into practice - Principles and hypotheses for interventions addressing multiple behaviors in primary care. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2):88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerr EA, McGlynn EA, Adams J, Keesey J, Asch SM. Profiling the quality of care in twelve communities: Results from the CQI study. Health Aff. 2004;23(3):247–56. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berendsen AJ, de Jong GM, Jong BM-D, Dekker JH, Schuling J. Transition of care: experiences and preferences of patients across the primary/secondary interface - a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 18 kb)