Abstract

Mental health professionals from North America and Europe have become common participants in postconflict and disaster relief efforts outside of North America and Europe. Consistent with their training, these practitioners focus primarily on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as their primary diagnostic concern. Most research that has accompanied humanitarian aid efforts has likewise originated in North America and Europe, has focused on PTSD, and in turn has reinforced practitioners’ assumptions about the universality of the diagnosis. In contrast, studies that have attempted to identify how local populations conceptualize posttrauma reactions portray a wide range of psychological states. We review this emic literature in order to examine differences and commonalities across local posttraumatic cultural concepts of distress (CCDs). We focus on symptoms to describe these constructs – i.e., using the dominant neo-Kraepelinian approach used in North American and European psychiatry – as opposed to focusing on explanatory models in order to examine whether positive comparisons of PTSD to CCDs meet criteria for face validity. Hierarchical clustering (Ward’s method) of symptoms within CCDs provides a portrait of the emic literature characterized by traumatic multifinality with several common themes. Global variety within the literature suggests that few disaster-affected populations have mental health nosologies that include PTSD-like syndromes. One reason for this seems to be the almost complete absence of avoidance as pathology. Many nosologies contain depression-like disorders. Relief efforts would benefit from mental health practitioners getting specific training in culture-bound posttrauma constructs when entering settings beyond the boundaries of the culture of their training and practice.

Keywords: trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, cultural concepts of distress, emergency settings, humanitarian intervention

From beginnings in Cambodian refugee camps (Mollica et al., 1992; Mollica & Donelan, 1993) to tsunamis in Sri Lanka (e.g., Catani et al., 2009) earthquakes in Haiti (Raviola, Eustache, Oswald, & Belkin, 2012), and political upheaval across Africa (Stepakoff et al., 2006) and the Middle East (Almakhamreh & Lewando Hundt, 2012), the past decades have witnessed an exponential rise of trauma treatment as an integral part of international disaster relief. The psychological disorder of primary concern to relief efforts is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD and its antecedents (“railway spine,” “shell shock”; Jones, Fear, & Wessely, 2007; Jones et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2002; Young, 1997) have over a century of well-documented history in North American and European psychiatric traditions, and current versions are clearly codified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association), 2013) and the International Classification of Disorders, Tenth Edition (ICD-10; World Health Organization, 2008). However, most modern disasters and humanitarian aid crises occur outside of North America and Europe – i.e., outside of the cultural context in which PTSD was identified and has developed. This leaves most clinicians who join humanitarian aid efforts at a disadvantage concerning how posttrauma reactions are conceptualized and expressed by the populations they encounter.

The potential mismatch between DSM and ICD mental health models of posttraumatic stress and the cultures of most disaster settings has not gone unnoticed. The 2007 United Nations Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings exhort humanitarian aid workers to “tailor assessment tools to the local context” and to “not use assessment tools not validated in the local, emergency-affected context” (IASC, 2007, p. 14). Partly in response to such concerns, a number of researchers have applied PTSD measures in disaster-affected populations outside of North America and Europe in order to test the diagnosis’ cross-cultural validity. Numerous studies document that individuals within such populations endorse PTSD symptoms on questionnaires (de Jong et al., 2001; Fox, & Tang, S. S., 2000; Ichikawa, Nakahara, & Wakai, 2006; Sachs, Rosenfeld, Lhewa, Rasmussen, & Keller, 2008; Shrestha et al., 1998) and structured clinical interviews (Neuner, Schauer, Klaschik, Karunakara, & Elbert, 2004; Rasmussen, Rosenfeld, Reeves., & Keller, 2007), and that the variance within summary transformations of these responses (e.g., mean scores) is positively associated with the number of potentially traumatic events that they report (Cardozo, Vergara, Agani, & Gotway, 2000; Fawzi et al., 1997; Marshall, Schell, Elliott, Berthold, & Chun, 2005; Mollica et al., 1999). A subliterature using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) suggests that these responses are also associated with one another in ways that are similar to associations seen in North American and European samples, with a four-factor model consisting of intrusion, avoidance, numbing, and hyperarousal supported across studies (Palmieri, Marshall, & Schell, 2007; Rasmussen, Smith, & Keller, 2007; Vinson & Chang, 2012). For many, the recognition of symptoms, the internal consistency of measures, and partial configural invariance across cultures provides evidence that “the time has come to end the debate about the validity of the PTSD diagnosis” (Friedman, Resick, & Keane, 2007, p.13).

But answering the question of whether or not PTSD is universally valid is limited by the etic epistemology of the majority of trauma research. Etic research relies on interpreting information from observers’ perspectives; etic research is contrasted to emic research, which relies on interpretation by cultural insiders. Etic trauma literature has produced valuable confirmation of PTSD symptom clusters in multiple disaster settings outside of North America and Europe. However, most of the trauma literature is based on designs that use measures of PTSD without (1) exploring whether all symptoms of PTSD are relevant to local beliefs about the consequences of trauma or (2) examining whether there might be symptoms not included on these measures that might also be relevant. This makes this literature subject to Arthur Kleinman’s category fallacy (Kleinman, 1977), the assumption that because phenomena can be identified in different cultural settings they have the same meaning across these settings. In other words, attempts to establish cross-cultural construct validity of PTSD using PTSD measures are etic attempts to answer emic questions. Bracken and colleagues note that the designs of these studies “emphasize similarities in responses to trauma between cultural groups, while at the same time underestimating the differences because of the ‘universalist’ approach” (Bracken, Giller, & Summerfield, 1995, p. 1074).

Calls for research that examines local trauma constructs and meanings (e.g., Ager, 1997) have not gone unheard. A small number of peer reviewed manuscripts published over the past few decades use emic designs to explore local mental health constructs – the idioms of distress and culture-bound syndromes known in the DSM-5 as cultural concepts of distress (CCDs) – in trauma exposed populations. In order to avoid the category fallacy, these studies include design elements that allow for local constructions of distress, including the description of how symptoms connect to syndromes by traditional healers and those experiencing them. Studies also vary with respect to involvement with populations, from quick ethnography (a brief process of free listing and key informant interviews; Bolton & Tang, 2004; Handwerker, 2012) to in-depth, prolonged engagement. Although primarily qualitative, this literature also includes quantitative and mixed methods research as well. To date there are no summary reviews of this emic literature as it pertains to trauma; the current review is an attempt to remedy this.

The intended audience for this review are clinicians and researchers working in disaster mental health and psychosocial humanitarian aid outside of North America and Europe – i.e., beyond the cultural boundaries of the DSM’s nosological system. In order to present findings in the language of the DSM – the language of most professional mental health training – we took a neo-Kraepelinian, purposefully atheoretical, symptom-based approach in our reivew. This review was challenged by the multiple methods that exist in the literature. To date, no meta-analysis analog for literature with both qualitative and quantitative findings has been developed. In order to appropriately characterize the symptom profiles that exist in the emic trauma literature we took a quantitative approach that relied upon coding and categorizing symptoms within posttrauma CCDs and then using hierarchical clustering to identify commonly occurring symptom profiles among CCDs. Findings comprise a description of the methods used in the literature, a brief qualitative summary, and a cluster analysis of CCDs based on their symptom profiles.

Methods

Study selection

We undertook a literature search using scholarly databases, examining the tables of contents of special issues of journals focusing on culture and trauma, soliciting suggestions from researchers with experience in emic mental health research, and reviewing reference sections of relevant articles. We first searched MEDLINE, PsychINFO, PILOTS, Science Direct and Scopus using the search terms “idioms of distress,” “culture bound syndromes,” and “emic,” combined with “trauma,” “disaster,” “armed conflict,” “political violence,” “refugees,” “torture,” and “war.” We next examined study abstracts to identify studies that satisfied the following inclusion criteria: (a) sampling trauma-affected populations (including those exposed to war, natural disasters, or other potentially traumatic events), (b) utilizing emic designs, (c) naming and describing the symptoms of specific CCDs and (d) published in peer-reviewed journals before December 31, 2013. Because of well-documented concerns about generalizability, we excluded studies relying on case studies alone. In order to draw upon the rigor of peer-reviewed research, we also excluded books, book chapters, unpublished theses and other non-peer reviewed material. From an initial sample of 5,341 citations gleaned from the database searches we narrowed the field to 55 unique studies. We identified 38 studies in scholarly databases. Reviewing special issues on culture and trauma resulted in eight additional articles. Contacting authors in the field resulted in four more. Examining references during our review of articles resulted in three additional references. Finally, the peer review process for publication here resulted in two articles that our search strategies did not identify. Where we found multiple articles from the same investigations, we made attempts to review the publications that fit our criteria best. For example, Hinton has published multiple articles describing khyâl attacks; we chose the most detailed description that referenced the relation to trauma (Hinton, Pich, Marques, Nickerson, & Pollack, 2010a).

Each study was coded for design characteristics (study population, location, type of sample, and methods used) and each CCD was coded for symptoms and whether or not it was explicitly associated with traumatic events (the gateway criterion for PTSD in DSM nosology). Symptoms were categorized using the four PTSD clusters outlined by DSM-5 – intrusion, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, hyperarousal – and those not associated with PTSD but identified with trauma in reviews of the cross-cultural trauma literature (Hinton & Lewis-Fernandez, 2011; Marsella, Friedman, & Spain, 1996): social isolation, rumination, anger, nontraumatic dissociation (e.g., dissociation during possession trances), vegetative depression symptoms, somatization, and psychotic symptoms. Coding DSM-5 symptoms relied heavily on Friedman and colleagues’ (Friedman, Resick, Bryant, & Brewin, 2011) rationale for changes to PTSD from DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) to DSM-5.

Primary coding was done by the first author, a clinical psychologist from the U.S. with a decade of research and practice working with refugees, torture survivors, and other survivors of political violence in home countries (Rasmussen, Rosenfeld, et al., 2007), refugee camps (Rasmussen, Katoni, Keller, & Wilkinson, 2011; Rasmussen et al., 2010), and resettlement contexts in the U.S. (Raghavan, Rasmussen, Rosenfeld, & Keller, 2012; Rasmussen, Smith, et al., 2007). A randomly selected 15 CCDs were also coded by the third author,i an Australian clinical psychologist with graduate and postdoctoral experience in posttrauma settings in Southeast Asia and clinical experience with PTSD and complicated grief. As presented in Table 1, kappa interrater reliability coefficients showed that symptom types were coded reliably, with the exception of nontraumatic dissociation, which was therefore excluded from analyses.

Table 1.

Stressors and symptoms for cultural concepts of distress

| Examples | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Proximal stressor etiology | ||

| None noted | 10 (8.6%) | |

| Discrete fear events | Sudden shock, like witnessing murder of relative; fright; excess indignation at being victimized; sexual assault | 18 (15.5%) |

| Chronic stressors | War-related persistent stressors; overwhelming loss; injustice | 48 (41.4%) |

| Chronic stressors or discrete fear events | (See examples above) | 20 (17.2%) |

| Supernatural causes | Supernatural presence in nightmares due to not observing proper burial rituals; souls of dead haunting living | 11 (9.5%) |

| Chronic stressors or supernatural causes | (see examples above) | 7 (6.0%) |

| Unclear | (no specified stressors) | 2 (1.7%) |

|

| ||

| Symptoms | Kappa (p-value) | |

| Intrusion | .587 (.013) | 26 (22.4%) |

| Avoidance | .634 (.008) | 5 (4.3%) |

| Negative cognitions & mood | .762 (.002) | 101 (87.1%) |

| Anger | .762 (.002) | 32 (27.6%) |

| Hyperarousal | .857 (.001) | 69 (59.4%) |

| Isolation | .727 (.003) | 32 (27.6%) |

| Rumination | .609 (.010) | 50 (43.1%) |

| Vegetative symptoms | .700 (.007) | 61 (52.6%) |

| Somatic symptoms | .634 (.008) | 70 (60.3%) |

| Psychotic symptoms | .634 (.008) | 26 (22.4%) |

| Nontraumatic dissociation | .286 (.255) | 6 (5.2%) |

In order to examine commonality across CCDs, we clustered symptoms using Ward’s method of hierarchical clustering. Hierarchical cluster analysis provides a range of groupings (or clusters; here interpreted as common symptom profiles) of cases suggested by a branching tree diagram called a dendrogram that indicates how similar cases are to one another by arranging them spatially (with the cases – here CCDs – arranged as the “leaves” at the end of the “branches” of the diagram). Inputs for the current review were the symptoms associated with CCDs: intrusion, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, hyperarousal, social isolation, rumination, vegetative symptoms, somatic symptoms, and psychotic symptoms (anger was not included in clustering as it met criteria for negative mood). Common symptom profiles (the clusters) were compared using chi-square tests.

Results

Table 2 presents the 55 studies that met our inclusion criteria, 116 CCDs (with English translations where provided), and methodological information for each study. Data were from 38 distinct non-European origin groups originating in Africa (n = 17 studies), the Americas (n = 14), the Middle East (n = 2), and other parts of Asia (n = 23). Studies were undertaken in 32 different countries. Samples included community members in their home regions (n = 35 studies), internally displaced persons (n = 4), and refugees (n = 17); four studies used multiple samples.

Table 2.

Studies reviewed

| Study | CCDsa | Cultural group | Country of study |

Sample type | Emic approaches |

Analytic methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abramowitz (2010) | open mole (sunken fontanelle) | Liberians | Liberia | traditional healers, health care providers, patients | participant observation, key informant interviews, ethnography | ethnography |

| Afana, et al. (2010) | faji’ah (tragedy), musiba (calamity), sadma (sudden blow), assabiah, araq, azma nafsiah, dag nafsi, qalaq, khofa | Palestinians | Palestine | community | ethnographic interviews | ethnography |

| Akello, Richters, & Reis (2006) | cen (spirit possession) | Acholi | Uganda | IDPsb | ethnography, clinical observation | ethnography |

| Baer, et al. (2003) | nervios, susto | Texas Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Ladino Guatemalans, Mexicans | U.S.A., Guatemala, Mexico | community | free listing, key informant interviews | content analysis |

| Betancourt, et al. (2009) | cen (spirit possession), kwo maraco/gin lugero, mwa lwor, two tam, par, kumu | Acholi | Uganda | IDPs | free listing, key informant interviews | content analysis |

| Bolton (2001) | agahinda (deep sadness/grief), akababaro, guhahamuka | Rwandans | Rwanda | community | free listing, key informant interviews | content analysis |

| Bolton, Surkan, Gray, & Desmousseaux (2012) | chok nan tèt (problems in the head), kè fe mal (suffering in the heart), yo kontinye soufrwi, chagren (sadness), moun yo panse anpil (thinking too much) | Haitians | Haiti | community | free listing, key informant interviews | content analysis |

| Caple James (2011) | sezisman | Haitians | Haiti | community | ethnography | ethnography |

| Chimm (2012) | baksbat (broken courage) | Khmer | Cambodia | professional & community “experts” | key informant interviews, case studies | ethnography |

| de Jong & Reis (2013) | kiyang-yang possession | Guinea Bissau | Guinea Bissau | community | ethnography | ethnography |

| Eisenbruch (1991) | “cultural bereavement” | Khmer | U.S.A., Australia | refugee children in foster care | ethnography, clinical observation | ethnography |

| Englund (1998) | spirit possession | Mozambiquean | Malawi | refugees | ethnography | ethnography |

| Familiar et al. (2013) | ihahamuka, ucutiyemera, akabonge, kwamana ubwoba, burenge | Burundian | Burundi | community | free listing, key informant interviews | content analysis |

| Fox (2003) | kidja farro (heart shakes), masilango (extreme fear), mira kurango (thinking sickness), perrio (brain out of place) | Mandingo | Gambia | traditional healers | vignettes, key informant interviews | grounded theory |

| Frye & D’Avanzo (1994) | koucharang (thinking too much) | Khmer | U.S.A. | refugees | participant observation, ethnographic interviews | content analysis |

| Guarnaccia, Canino, Rubio-Stipec, & Bravo (1993) | ataque de nervios | Puerto Ricans | U.S.A. | community | survey | variance-based methods |

| Henry (2006) | haypatensi | Mende | Sierra Leone | refugees | ethnographic interviews, participant observation | ethnography |

| Hinton, Um, & Ba (2001a) | kyol goeu (wind overload) | Khmer | U.S.A. | refugees | ethnography, case studies | content analysis |

| Hinton, Um, & Ba (2001b) | rooy go (sore neck syndrome) | Khmer | U.S.A. | refugees | ethnography, case studies | content analysis |

| Hinton, Hinton, Um, Chea, & Sak (2002) | khsaoy beh daung (weak heart) | Khmer | U.S.A. | refugees | clinical interviews, case studies | content analysis |

| Hinton, Hinton, Pham, Chau, & Tran (2003) | trúng gió (hit by the wind) | Vietnamese | U.S.A. | refugees | ethnographic interviews | phenomenology |

| Hinton, Pich, Chhean, & Pollack (2005) | khmaach sangkat (ghost pushes you down) | Khmer | U.S.A. | refugees | survey | variance-based methods |

| Hinton et al. (2007) | orthostatic panic attack | Vietnamese | U.S.A. | refugees | clinical interviews, case studies | content analysis |

| Hinton, Pich, Marques, Nickerson, & Pollack (2010b) | khâl attack | Khmer | U.S.A. | refugees | ethnography, survey | ethnography, variance-based methods |

| Igreja et al. (2010) | posession trance, ku tekemula (dissociative trace) | Mozambiqueans | Mozambique | community | survey | variance-based methods |

| Keys, et al. (2012) | tèt idioms, kè idioms | Haitians | Haiti | outpatients, key informants | participant observation, key informant interviews, focus groups, case studies | content analysis, pile sort, multidimensional scaling |

| Kohrt & Harper (2008) | pagal | Nepali | Nepal | community | ethnography, case studies | ethnography |

| Kohrt & Maharjan (2009) | dimag dysfunction | Nepali | Nepal | children exposed to trauma | ethnography, case studies | ethnography |

| Kohrt & Schrieber, (1999), Kohrt, et al., (2005) | jhum-jhum parasthesia | Nepali | Nepal | community | surveys, ethnography, life histories, medical exams | ethnography, variance-based methods |

| Kohrt & Hruschka (2010) | maansanik rog (mental illness), mannsanik aaghaat/piDaa (mental shock) | Nepali | Nepal | community | ethnographic interviews, free listing, comparison tasks, participant observation | thematic coding |

| Lewis-Fernandez, et al. (2010) | nervios, ataque de nervios | Caribbean Latinos | U.S.A. | community | survey | variance-based methods |

| Lim, et al. (2013) | seik hpizimu (mind/spirit suppression), seik lo’shaa, seik da’kya (spirit fall), seik daan yaa | Karen | Myanmar | local medics working with refugees | ethnographic interviews | grounded theory |

| Miller, et al. (2006) | asabi, fishar-e-bala (high blood pressure), fishar-e-payin (low blood pressure), jighar khun (bloody liver) | Afghanis (Dari speaking) | Afghanistan | community | vignettes comparing well and war affected | grounded theory |

| Norris, et al. (2001) | ataque de nervios | Mexicans | Mexico, U.S.A. | community | ethnographic interviews | thematic coding, card sort, K-means clustering |

| Pedersen, et al. (2010) | llaki, ñakary, tutal piensamentuwan, lukuyasca (craziness) | Qechua | Peru | community | ethnographic interviews | ethnography |

| Pike & Williams (2006) | think so much your head hurts, heart beats fast when you think | Turkana | Kenya | community | focus groups, key informant interviews (women only) | content analysis |

| Poudyal et al. (2009) | fear, thinking too much | Acehnese | Indonesia | community | free listing, key informant interviews | content analysis |

| Quinlan (2010) | chronic fright, normal or short fright | Dominica | Dominica | community | participant observation, free listing, survey | ethnography, frequency count |

| Rasmussen, et al. (2011) | hozun (deep sadness), majnun (madness) | Masalit (Darfuri) | Chad | refugees | free listing, key informant interviews | content analysis, card sort |

| Rees & Silove (2011) | sakit hati (sick heart), susah hati (troubled heart) | West Papuans | Australia | refugees | focus groups, ethnographic interviews | phenomenology |

| Reis (2013) | cen (spirit possession) | Acholi | Uganda | IDP former child soldiers | ethnography | ethnography |

| Salgado-de Snyder, et al. (2000) | nervios | Mexicans | Mexico | community | survey | variance-based methods |

| Sharma & van Ommeren (1998) | karmako phal | Bhutanese refugees | Nepal | refugees | ethnographic interviews | narrative analysis |

| Silove et al. (2009) | hirus nervusador | Timorese | East Timor | community | key informant interviews, case studies | content analysis |

| Stark (2006) | noro (spiritual polution) | Krio, Mende | Sierra Leone | IDP clinical sexual assault sample (girls only) | ethnographic interviews, participant observation, field notes | ethnography |

| Swagman (1989) | fijac | Yemenis | Yemen | community | survey, case studies | case studies, frequency counts |

| Tol, et al. (2010) | “trauma” | Sulawesi | Indonesia | community | focus groups, key informant interviews | grounded theory |

| van Duijl, et al. (2010) | okutembwa (spirit possession) | Acholi | Uganda | community | surveys with control group | variance-based methods |

| Ventevogel, et al. (2013) | moul, wehie arenjo/wehie arir (destroyed or disturbed mind), nger yec (cramped stomach); mamali (disturbed mind), ngengere, yeyeesi (many thoughts); erisire, amutwe alluhire (tired head); ibisazi, ibonge/akabonge, ihahamuka | Jo-Luo, Kawka; Wanande; Burundian | South Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi | community | focus groups, key informant interviews | content analysis |

| Warner (2007) | muchkej | Q’echi & K’iche Mayan women | Mexico | refugees | ethnography | ethnography, variance-based methods |

| Wikan (1989) | kesambet (shock and soul loss) | Balinese | Indonesia | community | ethnography, case studies | ethnography |

| Yarris (2011) | dolor de cerebro (brainache) | Nicaraguan | Nicaragua | community | ethnographic interviews (women only) | narrative analysis |

| Zarowsky (1997) | zar/wadaado (spirit possession), argegah, marrora dilla, murugo, niyed jab, waaliy, wareer | Somalis | Ethiopia | refugees | ethnography, life histories | ethnography |

| Zur (1996) | essence takes flight, spirit possession | Quiche Maya | Guatemala | community | ethnography, case studies | ethnography |

CCDs = cultural concepts of distress;

IDPs = internally displaced persons

Explicit emic approaches in the 55 studies included unspecified ethnography (n = 17), key informant interviews (n = 15), ethnographic interviewing (n = 12), surveys (n = 10), free listing (n = 9), participant observation (n = 7), focus groups (n = 5), clinical interviews and observation (n = 4), life histories (n = 3), presenting or eliciting clinical vignettes (n = 2), and comparison tasks (n = 1). Thirty-five studies included more than one approach. Thirty-seven reported surveys associated with their research, either as the primary design (the 10 reported above), or as an outcome of research activities. Although in many studies analyses were not made explicit (21 reported “ethnography” as an analysis), analyses included content analysis (n = 16), frequency counts and variance-based analyses (n = 11), card or pile sorts (n = 3; in one study this was followed by K-means clustering; Norris et al., 2001; and another by multidimensional scaling; Keys, Kaiser, Kohrt, Khoury, & Brewster, 2012), grounded theory (n = 4), phenomenology (n = 2), narrative analysis (n = 2) and thematic coding (n = 2). Eight of the 55 studies used multiple analytic approaches.

The 55 studies referred to 116 CCDs. Proximal stressor etiology (i.e., the specific event that precedes onset) and symptom counts are listed in Table 1. Stressor etiology varied, with some seeming to match DSM-5 Criterion A (e.g., witnessing the murder of relatives; Zarowsky, 1997), many related to chronic stressors that included but were not limited to Criterion A events (e.g., the Shining Path conflict in Peru; Pedersen, Kienzler, & Gamarra, 2010), and some related to the sufferer’s interaction with supernatural causes (e.g., not observing proper burial rituals; Englund, 1998). Two CCDs were without specific etiologic stressors altogether, but were reported as increasing following periods of trauma and increasing stressors. In addition, over half of CCDs (n = 67, 57.8%) were explicitly related to loss, either as part of etiologic chronic stressors or as an important exacerbating factor. The most common type of symptom reported among the studies was negative cognition and mood, with somatic symptoms and hyperarousal the next most common. The least common was avoidance.

Thirty of the 116 CCDs (25.8%) were described as parts of continua, related to other constructs in terms of being more or less severe. No continua were named. All continua included the concept that sufferers might transition from one level of severity to the next, often represented physiologically as rising from the heart or chest to the brain (e.g., Fox, 2003). In general continua were related to severity of etiology – i.e., a dose-response effect. Most CCDs were located within individuals. One CCD, ñakary (among Quechua in Peru; Pedersen, et al., 2010), was only used to describe collective suffering and another, baksbat (among Khmer in Cambodia; Chimm, 2012) was used to describe both collective and individual suffering.

Qualitative review of posttrauma CCDs

Most notable was the variety of symptoms and explanatory models represented. There were studies that described panic-like disorders (e.g., Latino Caribbean ataque de nervios; Lewis-Fernandez et al., 2010; and Cambodian khyâl attacks; Hinton, et al., 2010a), with hyperarousal and intrusion brought on by trauma cues and a relatively short course of illness. Others described problems more akin to depression (e.g., Ugandan Acholi two tam and mwa lwor; Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, & Bolton, 2009), with numbing (coded within negative cognitions and mood), rumination, and vegetative symptoms; some of these included hyperarousal symptoms as well (e.g., the three versions of nervios documented following trauma; Baer et al., 2003; Lewis-Fernandez, et al., 2010; Salgado-de Snyder, Diaz-Perez, & Ojeda, 2000). Several CCDs appeared very much like PTSD, some on their own (e.g., Nepali mannsanik aaghat; Kohrt & Hruschka, 2010) and some as part of continua (e.g., the Gambian Mandingo masilango to perrio continua; Fox, 2003). Several explicitly trauma-related disorders emphasized the experience of anger and intense rage (e.g., West Papuan saki hati; Rees & Silove, 2011). Spirit possession was reported in several African and Latin American studies (Betancourt, et al., 2009; Englund, 1998; van Duijl, Nijenhius, Komproe, Gernaat, & de Jong, 2010; Ventevogel, Jordans, Reis, & de Jong, 2013; Zur, 1996), with spirits of the dead revisiting trauma survivors and characterized symptomologically by intrusion, hyperarousal, and dissociation. Two CCDs drew upon hybrid explanatory models comprised of local conceptualizations and those brought by psychosocial humanitarian workers. Punya trauma in Indonesia (Tol, Reis, Susanty, & de Jong, 2010) and open mole in Liberia (Abramowitz, 2010) were both characterized by many types of symptoms (with the exception of avoidance), and were explained by vulnerability factors (e.g., having a sunken fontanel, or open mole; Abramowitz, 2010) and broad etiology comprised of traumatic events, chronic stressors, loss, interpersonal stressors and poverty.

Hierarchical clustering of symptoms across CCDs

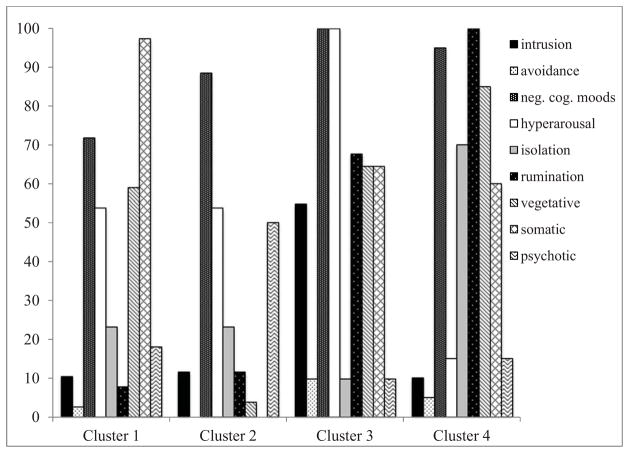

The dendrogram resulting from hierarchical clustering suggested two-, three-, and four-cluster solutions. The two- and three-cluster solutions were very general, grouping very different CCDs into one of the clusters. The four-cluster solution represented a more parsimonious balance. The number of CCDs within clusters in the four-cluster solution were as follows: Cluster 1, 39 (33.6% of all CCDs); Cluster 2, 26 (22.4%); Cluster 3, 31 (26.7%), and Cluster 4, 20 (17.2%). Figure 1 presents the percentage of CCDs within clusters that contained specific symptoms – i.e., the average symptom profiles of CCDs within clusters.

Figure 1.

Percentage of local constructs within clusters

In order to characterize clusters, we examined them for dominant symptom features, operationalized as appearing in over 80% of CCDs within clusters. Cluster 1 (n = 39), the largest of the clusters, was dominated by somatic symptoms, with 38 of the 39 CCDs (97.4%) featuring them. Also prominent (over 50%) were negative cognitions and mood (n = 28, 71.8%), vegetative symptoms (n = 23, 59.0%), and hyperarousal (n = 21, 53.8%). Cluster 1 was the most varied cluster, indicated by extreme branching within the cluster dendrogram. CCDs included Kareni seik lo’shaa (Lim, Stock, Oo, & Jutte, 2013), Latino susto (Baer et al, 2003), and Yemeni fijac (Swagman, 1989). Because of the prominence of somatic symptoms and nonspecific dysphoric symptoms, we labeled Cluster 1 somatic dysphoria.

Cluster 2 (n = 26) was dominated by negative cognitions and moods alone (n = 23, 88.5%). Half of CCDs in Cluster 2 also contained hyperarousal (n = 14, 53.0%) and psychotic symptoms (n = 13, 50.0%). Cluster 2 was also distinguished as the only cluster in which over half of CCDs featured anger (n = 15, 57.7%), a large component of negative cognitions and moods. CCDs included two versions of Acholi cen (Akello et al., 2006; Betancourt et al., 2009), Masalit majnun (Rasmussen et al., 2011), and Quechua lukuyasca (Pedersen et al., 2010). Because of this cluster included psychotic symptoms and anger with hyperarousal, we labeled this cluster behavioral disturbance.

Cluster 3 (n = 31) was dominated by hyperarousal (100.0%) and negative cognitions and mood (100.0%) and, although not dominant, also consisted of substantial rumination (n = 21, 67.7%), somatic (n = 20, 64.5%) and vegetative symptoms (n = 20, 64.5%), and intrusion (n = 17, 54.8%). Among the 31 CCDs within Cluster 1 were Rwandan guhahamuka (Bolton, 2001), Haitian kè idioms (Keys, et al., 2012), and Indonesian punya trauma (Tol, et al., 2010). Because of the dominance of hyperarousal with rumination and other nonspecific dysphoric symptoms, we labeled Cluster 3 anxious dysphoria.

The profile for Cluster 4 (n = 20) was similar to Cluster 3’s, but without hyperarousal. Cluster 4 was dominated by rumination (n = 20, 100.0%), negative cognitions and mood (n = 19, 95.0%), and vegetative symptoms (n = 17, 85.0%). Like Cluster 3, somatic symptoms were also common (n = 12, 60.0%), but unlike Cluster 3, so was isolation (n = 14, 70.0%). Included in Cluster 4 were Mandingo mira kurango (Fox, 2003), Afghani jighar khun (Miller et al., 2006), and Palestinian dag nafsi (Afana, Pedersen, Ronsbo, & Kirmayer, 2010). With rumination, vegetative symptoms, negative cognitions and moods, and isolation being prominent, we labeled this cluster depression.

In order to examine which types of symptoms contributed most to cluster profiles, we ran chi-square tests between clusters. Large differences were observed for somatic symptoms (χ2(df = 3) = 62.213, p < .001), rumination (χ2(df = 3) = 65.39, p < .001), vegetative symptoms (χ2(df = 3) = 35.61, p < .001), hyperarousal (χ2(df = 3) = 38.39, p < .001), intrusion (χ2(df = 3) = 25.597, p < .001), and isolation (χ2(df = 3) = 23.65, p < .001) Statistically significant but smaller differences were observed for psychotic symptoms (χ2(df = 3) = 15.35, p = .002) and negative cognitions and moods (χ2(df = 3) = 13.847, p = .003). Avoidance did not contribute to differences between clusters. When anger (not used for clustering) was disaggregated from negative cognition and mood, it accounted for 12.8%, 57.7%, 29.0% and 27.6% of clusters 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Anger was differentially distributed across clusters (χ2(df = 3) = 17.67, p = .001), more prominent in Cluster 2, behavioral disturbance, than others.

While comparing clusters we noted that vegetative and somatic symptoms seemed to vary together, and so ran a post-hoc analyses to test this perceived association. Categorical analyses suggested a significant positive association (χ2(df = 1) = 12.20, p < .001), with the odds ratio of one appearing in the presence of the other being 3.96 (95% CI 1.80, 8.73).

Discussion

The globalization of trauma treatment has been led primarily by mental health clinicians from North America and Europe, and, consistent with their training in DSM nosology, the primary mental health concern has been PTSD. However, the emic evidence base suggests that the DSM-5 model of PTSD is not congruent with most trauma-related mental health constructs around the world. This review of the emic literature on CCDs suggests that there is considerable global variety among conceptualizations of what constitutes trauma and a wide range of posttraumatic symptom presentations. Our findings support Hinton and Lewis-Fernandez’s (Hinton & Lewis-Fernandez, 2011) review of PTSD and culture that found “substantial cross-cultural variation” (p. 796) and emphasized the inclusion of somatic symptoms in posttraumatic symptomatology; however, we disagree with the authors that the evidence supports the conclusion that PTSD “constitutes a cohering group of symptoms” (p. 796) and is thus valid cross-culturally. Recognition of global variety has been present from the beginnings of modern psychiatric nosology, with Emil Kraepelin himself commenting upon it over a century ago (Kraepelin, 1904; cited in Jilek, 1995). Our findings suggest that diagnostic as well as symptomatic heterogeneity should be a more familiar theme in the modern trauma literature.

Several findings suggest that simply importing PTSD into modern disaster settings is neither culturally valid nor clinically sufficient. That we found four clusters of posttrautmatic CCDs suggests that traumatic multifinality (i.e., the existence of a range of posttrauma sequelae) is the dominant characteristic of the emic trauma literature. We found no obvious distinctions between constructs related specifically to trauma and those related to chronic stressors or substantial loss. Some constructs, notably those with supernatural causes, were phenomenologically grounded outside of what North American and European mental health practitioners would consider stressor criteria. Although we noted that our Cluster 3, anxious dysphoria, was the cluster most similar to DSM-5 PTSD in that it contained high negative cognitions and mood and hyperarousal and the highest proportion of CCDs with intrusion, intrusion was present in only over half of the CCDs, and pathological avoidance was completely absent. That psychotic symptoms were features of almost a fifth of all CCDs supports epidemiological findings that some psychotic symptoms following trauma may not be uncommon among non-European populations (Crager, Chu, Link, & Rasmussen, 2013).

Perhaps the most striking finding of this review concerns the relative salience of avoidance to posttraumatic CCDs. That the central position of avoidance in PTSD lacked cross-cultural face validity may seem to contradict the many etic studies that find that non-European posttrauma samples endorse avoidance items (e.g., Fox, & Tang, 2000). However, it is consistent with lower endorsement of DSM-IV’s avoidance/numbing cluster reported in specific studies (McCall & Resick, 2003) and noted in relevant reviews (Hinton & Lewis-Fernandez, 2011; Marsella, et al., 1996). Moreover, in several studies avoidance has shown little to no discriminant validity predicting individuals with posttraumatic distress and impairment (Kohrt et al., 2011; Neugebauer et al., 2009).

That very few CCDs included avoidance as a pathological symptom may suggest that avoidance is better conceptualized as a coping mechanism (that may be considered adaptive or maladaptive) than pathology. Conceptualizing avoidance as coping does not remove its central role in empirically supported trauma treatment, as it can still be modeled as a barrier to habituation (e.g., Jaycox, Foa, & Morral, 1998). A coping interpretation constructs avoidance as a rational response to be overcome (which is likely more palatable to sufferers than pathology). An anonymous reviewer suggested that perhaps social isolation, a feature in a quarter of the CCDs in our review, might be a proxy for avoidance. Although there may be good reasons to think that isolation in posttrauma contexts might be an attempt to avoid reminders of trauma – i.e., a coping strategy based avoiding ever present trauma cues – we did not find that isolation was associated with other features of PTSD in the manner that avoidance is in the DSM-5. Instead, isolation was a feature of the cluster related to behavioral disturbances – as has been noted previously (Ventevogel et al., 2013).

That we found four clusters of CCDs within the emic literature supports concerns that applying PTSD in modern disaster settings risks committing Kleinman’s category fallacy. However, the risks of doing this are not limited to diagnostic inaccuracies. Two posthumanitarian CCDs, punya trauma (Tol, et al., 2010) and open mole (Abramowitz, 2010), suggest that a North-South transfer of DSM culture can occur through aid programs promoting the use of trauma-related language. That these CCDs are largely nonspecific suggests that discussing DSM notions of trauma and PTSD may result in the everyday usage of terms that collapse PTSD, depression, and a host of other stressor-related mental health issues. These terms do not fit rigorous taxonometric notions of discrete categories, and given that most cultures seem to have working nosologies that include responses to extreme stressors, the taxonomy that results may actually be less well defined than before the arrival of disaster relief. Our review thus supports humanitarian aid programs that prioritize CCDs in assessment and treatment planning (e.g., Eisenbruch, de Jong, & van de Put, 2004; Mercer, Ager, & Ruwanpura, 2005), and the IASC guidelines that encourage these activities.

Global variety does not preclude commonality. Continua and dose-response effects were shared by several posttrauma nosologies. With strong components of negative cognitions and mood, rumination, and vegetative symptoms, our depression cluster fits symptomatically with the DSM-5’s Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), as well as notions of complicated grief. Although the absence of avoidance and presence of intrusion in less than half of the CCDs in the anxious dysphoria cluster suggests that it does not conform strictly to DSM-5 PTSD, there were notable similarities. PTSD and depression are common and often comorbid in posttrauma settings, and some have suggested that in the presence of trauma together they form a general chronic traumatic stress factor (O’Donnell, Creamer, & Pattison, 2004). That anxious dysphoria, somatic dysphoria, and depression combined account for over three quarters of the CCDs suggests that the majority of CCDs are symptomatically familiar to clinicians educated in North American and European traditions. Moreover, although not a culturally valid practice, the three clusters together also suggest that the common practice of using PTSD and depression measures in disaster settings has often tapped into sets of symptoms indicative of severe distress on emic as well as etic terms.

The central message of this review – global variety with common themes – is supported by findings from three epidemiological studies that have measured both CCDs and DSM constructs and found overlap in variance. In a sample of tsunami-affected Sri Lankans, Fernando (2008) administered a locally developed scale and the PTSD Checklist, Civilian version (PCLC, Weathers, Litz, Huska, & Keane, 1994), and found a high correlation between the two scales. In a sample of Darfur refugees, Rasmussen and colleagues (2011) used a similar approach with a scale measuring hozun and majnun (deep sadness and “madness”), the PCLC and depression items from the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). Intercorrelations were high, and hozun accounted for more variance in trauma events, daily stressors, and functional impairment did than PTSD or depression (Rasmussen, et al., 2011; Rasmussen, et al., 2010). In a war-affected sample in Sri Lanka, Jayawickreme and colleagues (Jayawickreme, Jayawickreme, Atanasov, Goonasekera, & Foa, 2012) found higher correlations between functional impairment and a locally developed scale than between functional impairment and the PTSD Symptom Scale—Self Report (PSS; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993), and when PSS scores were entered into a regression model predicting impairment following local scale scores they did not explain any additional variance. These emic-etic studies together suggest that DSM-based and locally developed measures often account for substantial shared variance in functioning, but that locally developed measures account for more. Unfortunately, a recent review of CCDs in mental health epidemiology found few high quality studies (Kohrt et al., 2013), and concluded that more research was needed to produce practicable tools for clinical assessment and monitoring and evaluation of global mental health programs.

Limitations

There are several noteworthy limitations to this review. The first concerns inclusion and exclusion criteria. The decision to exclude case studies may seem unnecessarily strict, as several case studies have been particularly illuminative of CCDs. For instance, Hagengimana and Hinton (Hagengimana & Hinton, 2009) provided an in-depth study of Rwandan ihahamuka using case studies that is more detailed than other studies from Rwanda and Burundi. Other studies were excluded because they identified symptoms without specifically naming the constructs that the symptoms indicated (e.g., Jayawickreme, Jayawickreme, Goonasekera, & Foa, 2009). Others were excluded even though they were examples of good emic practice because their purpose was to adapt measures of DSM constructs to particular cultural contexts (e.g., Kohrt, et al., 2011; Mollica, et al., 1992; Phan, Steel, & Silove, 2004), were not related to trauma or stress (Kohrt, Hruschka, Kohrt, Panebianco, & Tsagaankhuu, 2004), or provided insufficient detail on specific CCDs (e.g., Yoeli-Tlalim, 2010).

By treating studies relying on laypeople, patients, and traditional healers as equal, the current review collapses popular and expert nosologies. Future emic work should explicitly label sources as popular or expert so as to avoid the false parallelism between lay concepts of distress and DSM disorders that plagues the current literature. Another limitation concerns the time course of symptoms. With notable exceptions (Hinton, et al., 2010a; Quinlan, 2010), most studies in the review did not report time since exposure to trauma events or the course of CCDs, both of which have been shown to be important to symptom presentation among trauma-affected populations in North America and Europe (O’Donnell, et al., 2004). Future emic studies should include time since trauma and how symptom presentations change over time. Because of the small number of studies with children only, we also did not code for whether or not CCDs were specific to children or not. In addition, although we felt justified collapsing idioms of distress and culture-bound syndromes into CCDs given that the distinction is not likely to be obvious to European or North American clinicians in disaster settings, we encourage researchers to conceptualize them separately in the future. They are different, and eventually there should exist a large enough emic literature to examine them separately.

This review does not settle the vexing question of what posttrauma syndromes might be valid cross-culturally. Grouping CCDs by symptoms does not produce the kind of “experience near” (Geertz, 1986, p. 124) information that reflects particular explanatory models or the subtle clinical distinctions between normative and pathological levels of distress that are often critical in discussions between clinicians and patients, and at the core of much criticism of etic perspectives (e.g., Elsass, 2001; Jenkins, 1996; Kirmayer, 2003; Kirmayer & Minas, 2000). In other words, our comparative symptom-based approach alone does not provide a sufficient rubric for assessing cross-cultural validity of a given disorder. However, we feel that comparing DSM disorders and CCDs at the symptom level is still a necessary step in this process, and note that if comparisons fail at the symptom level, they are likely to fail at deeper levels of meaning as well.

We should also acknowledge that our search strategy was not able to identify the relative importance of trauma versus the multiple severe stressors and loss experiences that might result in the wide range of responses reflected in our findings. Interpreting differences as due to culture alone may conflate cross-cultural differences with differences in the magnitude of stressors that exist for many outside of North America and Europe and the impact of those stressors socioeconomically. We feel this limitation points to a lack of clarity in the trauma concept in general, and not a limitation of the cross-cultural literature per se. PTSD’s Criterion A has long been interpreted widely within North America and Europe (for a discussion, see McNally, 2003), and the multiplicity of proximal stressor events among CCDs in this review suggests a wide interpretation globally as well.

Finally, we wish to make it clear that ours is a review of theories about symptoms connected to disorders and syndromes, and not a review of evidence that supports those theories per se. We do not draw conclusions about the prevalence of any CCDs, nor do we make strong claims about their construct validity beyond their legitimacy within the cultures in which they have been described. The reliability, various forms of validity, incidence and prevalence of particular CCDs are important issues that have been addressed to some extent in the current literature (e.g., Hinton & Lewis-Fernandez, 2011), but clearly there is much more work needed to understand posttraumatic stress as it occurs globally.

Implications

PTSD, like most psychiatric diagnoses, is one of what philosopher Ian Hacking calls human kinds (Hacking, 1995, 2000) – those hypothetical constructs described by social sciences that become reified through the consequences of their application and have profound effects on those to whom they are applied. Human kinds are distinct from natural kinds in that they appear in sciences that lack unifying paradigms in the Kuhnian sense (Kuhn, 1962), and arise within specific cultures and historical eras. One need only examine the considerable change over time in posttraumatic constructs that has taken place within North American and European medicine (Jones, et al., 2003; Jones, et al., 2002) to be convinced that PTSD is only one of a number of posttraumatic human kinds that can exist. This review provides cross-cultural parallels to the multiplicity of trauma responses seen in the historical record.

Emic research and clinical practice should build upon the strengths of the current emic literature and counter its weaknesses. In order to compare expert nosologies to DSM categories, studies should draw upon expert key informants as opposed to laypeople. Although not always an option in disaster settings, studies that allow for prolonged engagement are desirable in order to observe subtle distinctions between key elements of explanatory models and associated features. There should be more emic-etic designs that quantitatively compare CCDs to DSM-5 disorders to aid monitoring and evaluation and ensure that psychosocial aid workers are responsive to the people they serve using their cultural perspectives. Above all, clinical training should acknowledge the diversity of posttrauma conditions that exist and integrate this knowledge into assessment and practice.

Research highlights.

Emic literature describes diverse posttrauma cultural concepts of distress (CCDs)

Hierarchical clustering of symptoms summarizes this mixed methods literature

Four clusters: somatic dysphoria, depression, anxious dysphoria, behavioral disturbance

Anxious dysphoria was most like PTSD; many were depression-like disorders

Clinical assessment and program evaluation should account for CCDs

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by Award Number K23HD059075 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NIH/NICHD) and in part by a Young Scholars Award from the Foundation for Child Development (both awarded to the first author).

Footnotes

Sim and Wright (2005) suggest that n = 13 provides .80 power for judgments based on kappa statistics of values of 7.0 and above.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Andrew Rasmussen, Fordham University.

Eva Keatley, University of Windsor.

Amy Joscelyne, New York University School of Medicine, Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings (2007).

- Abramowitz SA. Trauma and the humanitarian translation in Liberia: The tale of the open mole. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2010;34:353–379. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afana A, Pedersen D, Ronsbo H, Kirmayer LJ. Endurance is to be shown at the first blow: Social representations and reactions to traumatic experiences in the Gaza strip. Traumatology. 2010;16(2):43–54. doi: 10.1177/1534765610365913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ager A. Tensions in the psychological discourse: Implications for the planning of interventions with war-affected populations. Development in Practice. 1997;7(4):402–407. doi: 10.1080/09614529754198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akello G, Richters A, Reis R. Reintegration of former child soldiers in northern Uganda: Coming to terms with children’s agency and accountability. Intervention. 2006;4(3):229–243. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0b013e3280121c00. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almakhamreh S, Lewando Hundt G. An examination of social work interventions for use with displaced Iraqi households in Jordan. European Journal of Social Work. 2012;15(3):377–391. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2010.545770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RD, Weller SC, de Alba Garcia JG, Glazer M, Trotter R, Pachter L, Klein RE. A cross-cultural approach to the study of the folk illness nervios. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2003;27(3):315–337. doi: 10.1023/A:1025351231862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Speelman L, Onyango G, Bolton P. A qualitative study of mental health problems among children displaced by war in northern Uganda. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2009;46(2):238–256. doi: 10.1177/1363461509105815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P. Local perception of the mental health effects of the Rwandan genocide. Journal of Nervous of Mental Disease. 2001;189(4):243–248. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200104000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Surkan PJ, Gray AE, Desmousseaux M. The mental health and psychosocial effects of organized violence: A qualitative study in northern Haiti. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2012;49(3–4):590–612. doi: 10.1177/1363461511433945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Tang AM. Using ethnographic methods in the selection of post-disaster, mental health interventions. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2004;19(1):97–101. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00001540. unavailable. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken PJ, Giller JE, Summerfield D. Psychological responses to war and atroctiy: The limitations of current concepts. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40(8):1073–1082. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00181-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caple James E. Haiti, insecurity, and the politics of asylum. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2011;25(3):357–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2011.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo BL, Vergara A, Agani F, Gotway CA. Mental health, social functioning, and attitudes of Kosovar Albanians following the war in Kosovo. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(5):569–577. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catani C, Kohiladevy M, Ruf M, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Treating children traumatized by war and Tsunami: A comparison between exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in North-East Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9(22) doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimm S. Baksbat (broken courgage): A trauma-based cultural syndrome in Cambodia. Medical Anthropology: Cross-Cultural Studies in Health and Illness. 2012;32(2):160–173. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2012.674078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crager M, Chu T, Link B, Rasmussen A. Forced migration and psychotic symptoms: An analysis of the National Latino and Asian American Study. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies. 2013;11(3):299–314. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2013.801737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JTVM, Komproe IH, Van Ommeren M, El Masri M, Araya M, Khaled N, Somasundaram D. Lifetime events and posttraumatic stress disorder in four postconflict settings. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:555–562. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JTVM, Reis R. Collective trauma processing: Dissociation as a way of processing postwar traumatic stress in Guinea Bissau. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2013;50(5):644–661. doi: 10.1177/1363461513500517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptoms Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13:595–605. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700048017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbruch M. From post-traumatic stress disorder to cultural bereavement: Diagnosis of Southeast Asian refugees. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;33(6):673–680. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbruch M, de Jong JTVM, van de Put W. Bringing order out of chaos: A culturally competent approach to managing the oroblems of refugees and victims of organized violence. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(2):123–132. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000022618.65406.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsass P. Individual and collective traumatic memories: A qualitative study of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in two Latin American localities. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2001;38:306–316. doi: 10.1177/136346150103800302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Englund H. Death, trauma, and ritual: Mozambican refugees in Malawi. Social Science & Medicine. 1998;46(9):1165–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)10044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Familiar I, Sharma S, Ndayisaba H, Munyentwari N, Sibomana S, Bass JK. Community perceptions of mental distress in a post-conflict setting: A qualitative study in Burundi. Global Public Health. 2013;8(8):943–957. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2013.819587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawzi MCS, Pham T, Lin L, Nguyen TV, Ngo D, Murphy E, Mollica RF. The validity of posttraumatic stress disorder among Vietnamese refugees. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10(1):101–108. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490100109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando GA. Assessing mental health and psychosocial status in communities exposed to traumatic events: Sri Lanka as an example. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(2):229–239. doi: 10.1037/a0013940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490060405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SH. The Mandinka nosological system in the context of post-trauma syndromes. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2003;40(4):488–506. doi: 10.1177/1363461503404002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SH, Tang SS. The Sierra Leonean refugee experience: Traumatic events and psychiatric sequelae. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2000;188(8):490–495. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MJ, Resick PA, Bryant RA, Brewin CR. Considering PTSD for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28(9):750–769. doi: 10.1002/da.20767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MJ, Resick PA, Keane TM. PTSD: Twenty-five years of progress and challenges. In: Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Resick PA, editors. Handbook of PTSD: Science and Practice. New York: Guilford PRess; 2007. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Frye BA, D’Avanzo C. Themes in managing culturally defined illness in the Cambodian family. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 1994;11(2):89–98. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn1102_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. Making experiences, authoring selves. In: Turner VW, Bruner EM, editors. The anthropology of experience. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press; 1986. pp. 373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia PJ, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Bravo M. The prevalence of ataques de nervios in the Puerto Rico Disaster Study. Journal of Nervous of Mental Disease. 1993;181(3):157–165. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacking I. The looping effects of human kinds. In: Sperber D, Premack D, Premack AJ, editors. Causal cognition: A multi-disciplinary debate. New York, NY: Clarendon Press/Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 351–383. [Google Scholar]

- Hacking I. The Social Construction of What? Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hagengimana A, Hinton DE. Ihahamuka, a Rwandan syndrome of response to the genocide: Blocked flow, spirit assault, and shortness of breath. In: Hinton DE, Good BJ, editors. Culture and panic disorder. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2009. pp. 205–229. [Google Scholar]

- Handwerker PW. Quick Ethnography: A Guide to Rapid Multi-Method Research. Altamira Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Henry D. Violence and the body: Somatic expressions of trauma and vulnerability during war. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2006;20(3):379–398. doi: 10.1525/maq.2006.20.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Hinton L, Tran M, Nguyen M, Nugyen L, Hsia C, Pollack MH. Orthostatic panic attacks among Vietnamese refugees. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2007;44(4):515–544. doi: 10.1177/1363461507081640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Hinton S, Pham T, Chau H, Tran M. ‘Hit by the wind’ and temperature-shift panic among Vietnamese refugees. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2003;40(3):342–376. doi: 10.1177/13634615030403003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Hinton S, Um K, Chea A, Sak S. The Khmer ‘weak heart’ syndrome: Fear of death from palpitations. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2002;39(3):323–344. doi: 10.1177/136346150203900303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Lewis-Fernandez R. The cross-cultural validity of posttraumatic stress disorder: Implications for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28:783–801. doi: 10.1002/da.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pich V, Chhean D, Pollack MH. “The ghost pushes you down’: Sleep paralysis-type panic attacks in a Khmer refugee population. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2005;42(1):46–77. doi: 10.1177/1363461505050710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pich V, Marques L, Nickerson A, Pollack MH. Khayl attacks: A key idiom of distress among traumatized Camobodia refugees. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2010a;34(2):244–278. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9174-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pich V, Marques L, Nickerson A, Pollack MH. Kyal attacks: A key idiom of distress among traumatized Cambodia refugees. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2010b;34:244–278. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9174-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Um K, Ba P. Kyol goeu (‘wind overload’) part I: A cultural syndrome of orthostatic panic among Khmer refugees. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2001a;38(4):403–432. doi: 10.1177/136346150103800401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Um K, Ba P. A unique panic-disorder presentation among Khmer refugees: The sore-neck syndrome. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2001b;25(3):297–316. doi: 10.1023/A:1011848808980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa M, Nakahara S, Wakai S. Cross-cultural use of the predetermined scale cutoff points in refugee mental health research. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41(3):248–250. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igreja V, Dias-Lambranca B, Hershey DA, Racin L, Richters A, Reis S. The epidemiology of spirit possession in the aftermath of mass political violence in Mozambique. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71:592–599. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayawickreme N, Jayawickreme E, Atanasov P, Goonasekera MA, Foa EB. Are culturally specific measures of trauma-related anxiety and depression needed? The case of Sri Lanka. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24(4):791–800. doi: 10.1037/a0027564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayawickreme N, Jayawickreme E, Goonasekera MA, Foa EB. Distress, wellbeing and war: Qualitative analyses of civilian interviews from north eastern Sri Lanka. Intervention. 2009;7(3):204–222. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0b013e328334636f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Foa EB, Morral AR. Influence of emotional engagement and habituation on exposure therapy for PTSD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(1):185–192. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JH. Culture, emotion, and PTSD. In: Marsella AJ, Friedman MJ, Gerrity ET, editors. Ethnocultural aspects of posttraumtic stress disorder: Issues, research, and clinical applications. Vol. 576. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jilek WG. Emil Kraepelin and comparative sociocultural psychiatry. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1995;27:433–437. doi: 10.1007/BF02191802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E, Fear NT, Wessely S., Writers Shell shock and mild traumatic brain injury: A historical review. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1641–1645. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E, Hodgins-Vermaas R, McCartney H, Beech C, Palmer I, Hyams K, Wessely S. Flashbacks and post-traumatic stress disorder: The genesis of a 20th-century diagnosis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:158–163. doi: 10.1192/bjp.02.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E, Hodgins-Vermaas R, McCartney H, Ereritt B, Beech C, Poynter D, Wessely S. Post-combat syndromes from the Boer war to the Gulf war: A cluster analysis of their nature and attribution. British Medical Journal. 2002;324:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7333.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys HM, Kaiser BN, Kohrt BA, Khoury NM, Brewster AT. Idioms of distress, ethnopsychology, and the clinical encounter in Haiti’s Central Plateau. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75(3):555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ. Failures of imagination: The refugee’s narrative of psychiatry. Anthrppology & Medicine. 2003;10(2):167–185. doi: 10.1080/1364847032000122843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Minas H. The future of cultural psychiatry: An international perspective. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;45(5):438–447. doi: 10.1177/070674370004500503. unavailable. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Depression, somatization and the “new cross-cultural psychiatry”. Social Science & Medicine. 1977;11(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(77)90138-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Harper I. Navigating diagnoses: Understanding mind-body relations, mental health, and stigma in Nepal. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2008;32:462–491. doi: 10.1007/s11013-008-9110-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Hruschka DJ. Nepali concepts of psychological trauma: the role of idioms of distress, ethnopsychology and ethnophysiology in alleviating suffering and preventing stigma. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2010;34(2):322–352. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9170-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Hruschka DJ, Kohrt HE, Panebianco NL, Tsagaankhuu G. Distribution of distress in post-socialist Mongolia: A cultural epidemiology of yadargaa. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58(3):471–485. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Jordans MJ, Tol WA, Luitel NP, Maharjan SM, Upadhaya N. Validation of cross-cultural child mental health and psychosocial research instruments: Adapting the Depression Self-Rating Scale and Child PTSD Symptom Scale in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(127) doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Kunz RD, Baldwin JL, Koirala NR, Sharma VD, Nepal MK. “Somatization” and “comorbidity”: A study of jhum-jhum and depression in rural Nepal. Ethos. 2005;33(1):125–147. doi: 10.1525/eth.2005.33.1.125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Maharjan SM. When a child is no longer a child: Nepali ethnopsychology of child development and violence. Studies in Nepali history and Soceity. 2009;14(1):107–142. unavailable. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Rasmussen A, Kaiser BN, Haroz EE, Maharjan SM, Mutamba BB, Hinton DE. Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2013:1–42. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Schrieber SS. Jhum-jhum: Neuropsychiatric symptoms in a Nepali village. The Lancet. 1999;353(9158):1070. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05782-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernandez R, Gorritz M, Raggio GA, Pelaez C, Chen H, Guarnaccia PJ. Association of trauma-related disorders with four idioms of distress among Latino psychiatric outpatients. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2010;34(2):219–243. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9177-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim AG, Stock L, Oo EKS, Jutte DP. Trauma and mental health of medics in eastern Myanmar’s conflict zones: a cross-sectional and mixed methods investigation. Conflict and Health. 2013;7(15) doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsella AJ, Friedman MJ, Spain EH. Ethnocultural aspects of posttraumatic stress disorder: Issues, research, and clinical applications. In: Marsella AJ, Friedman MJ, Gerrity ET, Scurfield RM, editors. Ethnocultural aspects of posttraumatic stress disorder: Issues, research, and clinical applications. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 1996. pp. 105–129. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GN, Schell TL, Elliott MN, Berthold SM, Chun CA. Mental health of Cambodian refugees two decades after resettlement in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294(5):571–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall GJ, Resick PA. A pilot study of PTSD symptoms among Kalahari Bushmen. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16(5):445–450. doi: 10.1023/A:1025702326392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ. Progress and controversy in the study of posttraumatic stress disorder. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:229–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer SW, Ager A, Ruwanpura E. Psychosocial distress of Tibetans in exile: Integrating western interventions with traditional beliefs and practice. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(1):179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Omidian P, Quraishy AS, Quraishy N, Nasiry MN, Nasiry S, AYA The Afghan symptom checklist: A culturally grounded approach to menatl health assessment in a conflict zone. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(4):423–433. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, Lavelle J. The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire: Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. The Journal Of Nervous And Mental Disease. 1992;180(2):111–116. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RF, Donelan K. The effect of trauma and confinement on functional health and mental health status of Cambodians Living in Thailand-Cambodia border camps. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;270(5):581–587. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RF, McInnes K, Sarajlic N, Lavelle J, Sarajlic I, Massagli MP. Disability associated with psychiatric comorbidity and health status in Bosnian refugees living in Croatia. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(5):433–439. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer R, Fisher PW, Turner JB, Yamabe S, Sarsfield JA, Stehling-Ariza T. Post-traumatic stress reactions among Rwandan children and adolescents in the early aftermath of genocide. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38(4):1033–1045. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner F, Schauer M, Klaschik C, Karunakara U, Elbert T. A comparison of Narrative Exposure Therapy, supportive counseling, and psychoeducation for treating posttraumatic stress disorder in an African refugee settlement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(4):579–587. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Weisshaar DL, Conrad ML, Diaz EM, Murphy AD, Ibanez GE. A qualitative analysis of posttraumatic stress among Mexican victims of disaster. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14(4):741–756. doi: 10.1023/A:1013042222084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, Pattison P. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma: Understanding comorbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1390–1396. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri PA, Marshall GN, Schell TL. Confirmatory factor analysis of posttraumatic stress symptoms in Cambodian refugees. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20(2):207–216. doi: 10.1002/jts.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen D, Kienzler H, Gamarra J. Llaki and nakary: Idioms of distress and suffering among the Highland Quechua in Peruvian Andes. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2010;34(2):279–300. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9173-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan T, Steel Z, Silove D. An ethnographically derived measure of anxiety, depression, and somatization: the Phan Vietnamese Psychiatric Scale. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2004;41(2):200–232. doi: 10.1177/1363461504043565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike IL, Williams SR. Incorporating psychosocial health into biocultural models: Preliminary findings from Turkana women of Kenya. American Journal of Human Biology. 2006;18:729–740. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudyal B, Bass JK, Subyantoro T, Jaonathan A, Erni T, Bolton P. Assessment of the psychosocial and mental health needs, dysfunction and coping mechanisms of violence affected populations in Bireuen, Aceh. A qualitative study. Torture. 2009;19(3):218–226. unavailable. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan M. Ethnomedicine and ethnobotany of fright, a Caribbean culture-bound psychiatric syndrome. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2010;6(9) doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan S, Rasmussen A, Rosenfeld B, Keller AS. Correlates of symptom reduction in treatment-seeking survivors of torture. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2012;5(4):377–383. doi: 10.1037/a0028118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen A, Katoni B, Keller AS, Wilkinson J. Psychological Distress among Darfur Refugees: Hozun and Majnun. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2011;48(4):392–415. doi: 10.1177/1363461511409283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen A, Nguyen L, Wilkinson J, Raghavan S, Vundla S, Miller K, Keller AS. Rates and impact of trauma and current stressors among Darfuri refugees in eastern Chad. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(2):227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen A, Rosenfeld B, Reeves K, Keller AS. The effects of torture-related injuries on psychological distress in a Punjabi Sikh sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(4):734–740. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen A, Smith HE, Keller AS. Factor Structure of PTSD symptoms among West and Central African refugees. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20(3):271–280. doi: 10.1002/jts.20208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raviola G, Eustache E, Oswald C, Belkin GS. Mental health response in Haiti in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake: A case study for building long-term solutions. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2012;20(1):68–77. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2012.652877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees S, Silove D. Sakit Hati: A state of chronic mental distress related to resentment and anger amongst West Papuan refugees exposed to persecution. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis R. Children enacting idioms of witchcraft and spirit possession as a response to trauma: Therapeutically beneficial, and for whom? Transcultural Psychiatry. 2013;50(5):622–643. doi: 10.1177/1363461513503880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs E, Rosenfeld B, Lhewa D, Rasmussen A, Keller AS. Entering exile: Trauma, mental health, and coping among Tibetan refugees arriving in Dharamsala, India. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21(2):199–208. doi: 10.1002/jts.20324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado-de Snyder VN, Diaz-Perez MdJ, Ojeda VD. The prevalence of nervios and associated symptomatology among inhabitants of Mexican rural communities. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2000;24(4):453–470. doi: 10.1023/A:1005655331794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, van Ommeren M. Preventing torture and rehabilitating survivors in Nepal. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1998;35(1):85–97. doi: 10.1177/136346159803500104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]