Abstract

Autologous islet transplantation after total pancreatectomy is an excellent treatment for painful chronic pancreatitis. Traditionally, islets have been isolated without purification; however, purification is applied when the tissue volume is large. Nevertheless, the impact of tissue volume and islet purification on clinical outcomes of autologous islet transplantation has not been well examined. We analyzed 27 cases of autologous islet transplantation performed from October 2006 to January 2011. After examining the relationship between tissue volume and portal pressure at various time points, we compared islet characteristics and clinical outcomes between cases with complications (complication group) and without (noncomplication group), as well as cases with purification (purification group) and without (nonpurification group). Tissue volume significantly correlated with maximum (R = 0.61), final (R = 0.53), and delta (i.e., difference between base and maximum; R = 0.71) portal pressure. The complication group had a significantly higher body mass index, tissue volume, islet yield, and portal pressure (maximum, final, delta), suggesting that complications were associated with high tissue volume and high portal pressure. Only one of four patients (25%) in the complication group became insulin free, whereas 11 of 23 patients (49%) in the noncomplication group became insulin free with smaller islet yields. The purification group had a higher islet yield and insulin independence rate but had similar final tissue volume, portal pressure, and complication rates compared with the nonpurification group. In conclusion, high tissue volume was associated with high portal pressure and complications in autologous islet transplantation. Islet purification effectively reduced tissue volume and had no negative impact on islet characteristics. Therefore, islet purification can reduce the risk of complications and may improve clinical outcome for autologous islet transplantation when tissue volume is large.

Keywords: Autologous islet transplantation, Tissue volume, Purification, Portal thrombosis, Portal pressure

INTRODUCTION

Total pancreatectomy followed by autologous islet transplantation is an excellent option for the treatment of chronic pancreatitis with severe abdominal pain (7, 15,16). Traditionally, for autologous islet transplanta tion, chronically damaged pancreata with a limited amount of exocrine tissue have been digested for islet isolation without purification (4). However, the amount of exocrine tissue could be large, and this could result in portal hypertension or portal thrombosis. While cases of portal thrombosis after autologous islet transplantation have been reported, the relationship between tissue volume and complications has been unclear (7,20). Therefore, it is important to clarify the relationship between tissue volume and complications related to autologous islet transplantation.

In addition, it has been demonstrated that the function of transplanted islets is associated with the transplanted islet yields (1). In the process of islet purification, islets are inevitably lost; therefore, avoiding purification is advantageous in achieving excellent islet function. On the other hand, the avoidance of purification is associ ated with high tissue volume, which might be a risk factor for portal hypertension or portal thrombosis after autologous islet transplantation. Therefore, it is also important to assess the impact of islet purification on the clinical outcomes of autologous islet transplantation.

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed our 27 cases of autologous islet transplantation to determine the impact of tissue volume and islet purification on islet characteristics and clinical outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Autologous Islet Transplantation

This institutional review board-approved study involved a retrospective review of 27 cases of autolo gous islet transplantation after total pancreatectomy per formed at Baylor University Medical Center at Dallas from October 2006 to January 2011. Islet isolation was performed in the current good manufacturing practice facility at the Baylor Institute for Immunology Research in Dallas. University of Wisconsin solution was used for pancreas preservation in the initial three cases, and the oxygen-charged static two-layer method (11) was used for all other cases. Ductal injections (9) were performed in all cases except the initial two. Liberase HI (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), Collagenase NB with neutral prote ases (SERVA Electrophoresis GMbH, Heidelberg, Germany), or Liberase MTF (Roche) was infused into the main pancreatic duct for pancreas distension. Islets were isolated by the modified Ricordi method (8,14,17). When tissue volume exceeded approximately 15–20 ml, islets were purified with a COBE 2991 cell processor (CaridianBCT, Inc., Lakewood, CO) using a density- adjusted iodixanol-based continuous density gradient (12,13). The final preparation of islets was assessed by using dithizone staining (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for islet yield and purity (6). The islet yield was converted into a standard number of islet equivalents (IEQ, diameter standardizing to 150 μm) (10). Islet via bility was evaluated with fluorescein diacetate (10 μmol/ L) and propidium iodide (15 μmol/L) staining (10). The average viability of 50 islets was calculated. The tissue volume before and after purification was measured using a conical tube with a scale. The final products were assessed for sterility by the amount of endotoxin, gram staining, and bacterial and fungal cultures.

Isolated islets were infused into the portal vein via the mesenteric vein with heparin (70 U/kg body weight) while the patient was under general anesthesia (18). Portal vein pressure was monitored before islet infusion (basal) and during islet infusion. The highest portal pressure (maximum) and portal pressure at the end of islet infusion (final) were recorded. The difference between the basal and the maximum portal pressure was calcu lated (delta portal pressure). When the portal pressure exceeded 22 mmHg, the infusion was halted until the portal pressure decreased (18). If the portal pressure did not decrease and islet transplantation was not completed, the case was categorized as an incomplete islet transplantation. An incomplete islet transplant was consid ered a complication of portal hypertension.

Assessment of Clinical Outcomes

Clinical outcomes were assessed by insulin secretory ability from islets and clinical manifestation as described previously (19). In brief, when the C-peptide value was below the detection level of the assay (0.1 ng/ml), the islet function was defined as “no function.” When a patient achieved insulin independence, the islet function was defined as “full function.” Insulin independence was defined as receiving no exogenous insulin for 2 weeks or longer with excellent glycemic control by cap illary blood glucose measurements, according to the report of the Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry (3). Cases that did not meet the criteria for no function or full function were classified as partial function.

Both before and after autologous islet transplantation, the flow of the portal vein was assessed by Doppler echogram. When portal flow was not detected by Dopp ler echogram after transplantation, portal thrombosis was diagnosed. Portal thrombosis is considered a com plication related to autologous islet transplantation. To assess liver function, we measured patients’ serum lev els of released transaminases.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The relation between tissue vol ume and portal pressure was analyzed using simple lin ear regression. The averages of two groups were analyzed using the two-tailed t-test. The ratios of two groups were compared using Fisher's exact test or chi- square test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statisti cally significant. Values are shown as mean ± SE.

RESULTS

Relationship Between Tissue Volume, Portal Pressure and Liver Function

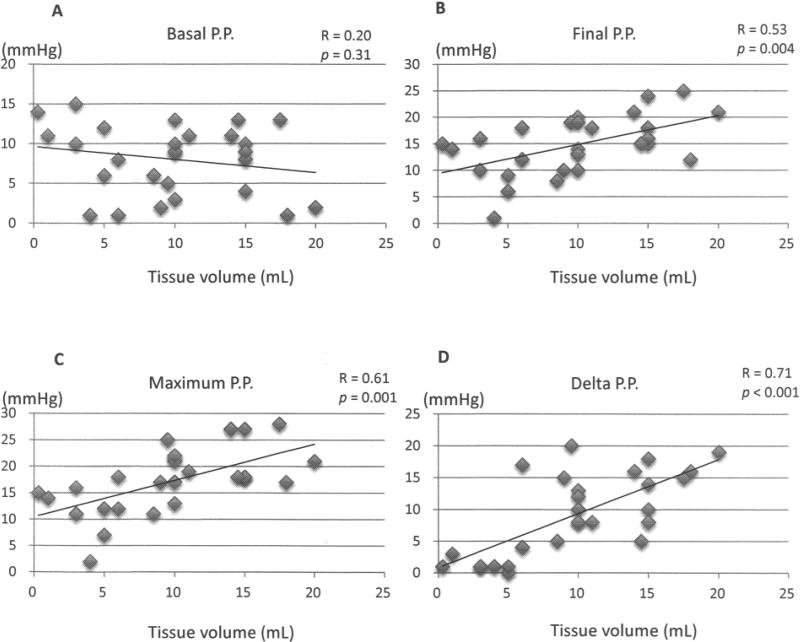

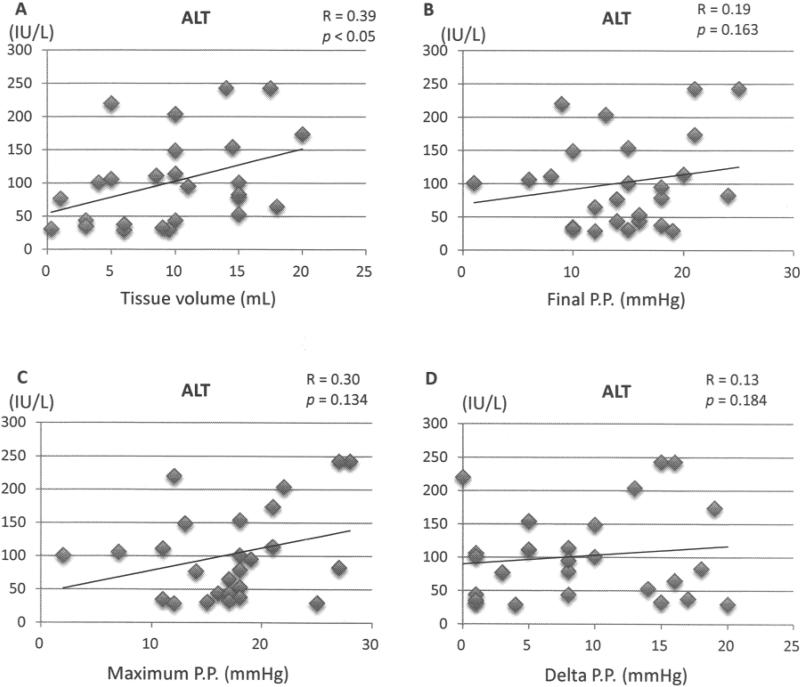

No correlation was found between tissue volume and basal portal pressure before islet infusion (Fig. 1A), but there was a significant correlation between tissue volume and final, maximum, and delta portal pressure (Fig. 1B–D), with the highest correlation for the delta portal pressure. There was a weak but significant correlation between tissue volume and blood levels of released liver enzymes (Fig. 2A). However, there were no significant correlations between the blood levels of released liver enzymes and portal pressure, including final, maximum, and delta portal pressure (Fig. 2B–D).

Figure 1.

Relationship between tissue volume and (A) basal portal pressure (PP), (B) final PP, (C) maximum PP, and (D) delta PP. R is correlation coefficient.

Figure 2.

Relationship between serum level of alanine transaminase (ALT) and (A) tissue volume, (B) final portal pressure (PP), (C) maximum PP, and (D) delta PP.

Impact of Complications

Four patients suffered a total of five complications associated with islet infusion, including two cases of portal hypertension with incomplete transplantation and three cases of portal thrombosis. One case had both por tal hypertension with incomplete transplantation and portal thrombosis. We categorized those four patients as the complication group and the other 23 patients as the noncomplication group. Table 1 compares the character istics and outcomes of complication cases and noncomplication cases. The two groups had no significant differences in gender, age, height, body weight, and pancreas weight, but those in the complication group had a significantly higher body mass index. The complication group had a significantly higher pellet size, final islet yield, and final islet yield per pancreas weight. There was no significant difference in purity and viability between the two groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics and Outcomes of the Complication Group and Noncomplication Group for Islet Transplantation

| Variable | Complication Group (n = 4) | Noncomplication Group (n = 23) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Gender (F/M) | 3/1 | 15/8 | 0.99 |

| Age (years) | 41 ± 2.0 | 39 ± 3.5 | 0.81 |

| Height (cm) | 164 ± 4.8 | 167 ± 2.6 | 0.69 |

| Body weight (kg) | 82 ± 6.5 | 69 ± 3.2 | 0.14 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.1 ± 1.1 | 24.8 ± 1.0 | <0.05 |

| Pancreas weight (g) | 94 ± 9.3 | 82 ± 5.9 | 0.43 |

| Islet characteristics | |||

| Pellet size (ml) | 16.9 ± 1.2 | 8.6 ± 1.0 | <0.01 |

| Final islet yield (IEQ) | 684,213 ± 72,799 | 366,420 ± 50,919 | <0.02 |

| Final islet yield/pancreas (IEQ/g) | 7,425 ± 1,046 | 3,950 ± 443 | <0.01 |

| Purity | 27.5 ± 8.3 | 39.3 ± 5.6 | 0.40 |

| Viability | 97.3 ± 1.0 | 96.5 ± 0.4 | 0.45 |

| Portal pressure | |||

| Basal (mmHg) | 8.2 ± 0.9 | 7.0 ± 2.5 | 0.62 |

| Max (mmHg) | 23.5 ± 2.4 | 16.2 ± 1.2 | <0.03 |

| Final (mmHg) | 21.5 ± 2.0 | 13.6 ± 1.0 | <0.01 |

| Delta (mmHg) | 16.5 ± 1.2 | 8.0 ± 1.3 | <0.02 |

| Islet function | |||

| Insulin independence | 1 | 11 | |

| Partial function | 3 | 12 | 0.40 |

| Nonfunction | 0 | 0 | |

| Sterility | |||

| Positive bacterial | 0 | 5 | 0.56 |

| Positive fungal | 0 | 1 | 1.00 |

Regarding portal pressure, there was no significant difference in the basal portal pressure, but maximum, final, and delta portal pressures were significantly higher in the complication group. This result suggests that a high tissue volume resulted in high portal pressure, which caused complications.

In the complication group, one patient achieved insulin independence (25%) and three patients had partial function. In the noncomplication group, 11 patients achieved insulin independence (49%) and 12 patients had partial function. There was no primary nonfunction in either group. There was no significant difference in islet function between the two groups. Since the average islet yield was significantly higher in the complication group, a 25% insulin independence rate seems unexpectedly low.

Regarding sterility, the complication group had no positive bacteria and fungal cultures, while the noncom plication group had five cases of positive bacterial culture and one case of positive fungal culture. This result was not statistically significant.

Impact of Islet Purification

Table 2 compares the characteristics and outcomes of the 13 purification cases and 14 nonpurification cases. There were no significant differences in gender, age, height, weight, and body mass index between the two groups; however, pancreas weight was significantly heavier in the purification group. Since the indication of islet purification depended on prepurification tissue volume, the prepurification tissue volume was signifi cantly higher in the purification group. After purification, there was no significant difference in tissue volume between the two groups. Before purification, both islet yield and islet yield per pancreas weight were signifi cantly higher in the purification group. After purification, islet yield was still significantly higher in the purification group. Purity was significantly higher in the purification group, and viability was similar between the two groups.

Table 2.

Characteristics and Outcomes of the Purification Group and Nonpurification Group for Islet Transplantation

| Variable | Purification Group (n = 13) | Nonpurification Group (n = 14) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | |||

| Gender (F/M) | 8/5 | 10/4 | 0.70 |

| Age (years) | 40 ± 3.2 | 40 ± 3.0 | 0.97 |

| Height (cm) | 166 ± 3.8 | 167 ± 2.8 | 0.91 |

| Body weight (kg) | 71 ± 3.2 | 72 ± 5.0 | 0.91 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.7 ± 1.0 | 25.6 ± 1.6 | 0.96 |

| Pancreas weight (g) | 96 ± 6.7 | 73 ± 6.8 | <0.05 |

| Tissue and islet characteristics | |||

| Prepurification tissue volume (ml) | 32.8 ± 3.9 | 8.1 ± 1.6 | <0.00001 |

| Final tissue volume (ml) | 11.7 ± 1.2 | 8.1 ± 1.6 | 0.09 |

| Pancreas weight (g) | 95.8 ± 6.7 | 73.2 ± 6.8 | <0.03 |

| Prepurification islet yield (IEQ) | 611,648 ± 64,084 | 315,436 ± 66,570 | <0.01 |

| Prepurification islet yield/weight (IEQ/g) | 6,423 ± 561 | 4,130 ± 738 | <0.03 |

| Final islet yield (IEQ) | 519,109 ± 63,742 | 315,436 ± 66,570 | <0.04 |

| Final islet yield/weight (IEQ/g) | 4,984 ± 544 | 4,130 ± 738 | 0.38 |

| Final purity (%) | 50.2 ± 3.8 | 24.8 ± 7.7 | <0.01 |

| Final viability (%) | 96.6 ± 0.5 | 96.6 ± 0.5 | 0.94 |

| Portal pressure | |||

| Basal portal pressure (mmHg) | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 9.5 ± 1.0 | 0.07 |

| Max portal pressure (mmHg) | 17.8 ± 1.9 | 16.8 ± 1.5 | 0.68 |

| Final portal pressure (mmHg) | 14.3 ± 1.7 | 15.2 ± 1.3 | 0.68 |

| Delta portal pressure (mmHg) | 11.3 ± 1.4 | 7.3 ± 1.9 | 0.11 |

| Islet function | |||

| Insulin independence | 7 | 5 | |

| Partial function | 6 | 9 | 0.34 |

| Nonfunction | 0 | 0 | |

| Sterility | |||

| Positive bacterial | 2 | 3 | 1.00 |

| Positive fungal | 1 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Complications | |||

| Portal thrombosis | 1 | 2 | 1.00 |

| Incomplete transplant | 1 | 1 | 1.00 |

In analyzing the effect of purification on portal pressure, no significant differences were seen in basal, maxi mum, and final portal pressure between the two groups. The delta portal pressure was higher in the purification group, but the difference was not significant. Overall, purification had no significant impact on portal pressure during autologous islet transplantation.

Seven out of 13 patients (53.8%) in the purification group and 5 out of 14 patients (35.7%) in the nonpurification group achieved insulin independence. In term of sterility, the ratio of positive bacterial culture was 2/13 (15.4%) in the purification group and 3/14 (21.4%) in the nonpurification group. The ratio of positive fungal culture was 1/13 (7.7%) in the purification group and 0/14 (0%) in the nonpurification group. In terms of islet infusion-related complication, the ratio of portal throm bosis was 1/13 (7.7%) in the purification group and 2/ 14 (14.3%) in the nonpurification group. The ratio of incomplete transplant was 1/13 (7.7%) in the purification group and 1/14 (7.1%) in the nonpurification group. None of these differences were statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that tissue volume was significantly correlated with portal pressure during autologous islet transplantation. Delta portal pressure in particular was most closely correlated with tissue vol ume. Previously, Sutherland et al. demonstrated that a large volume of transplanted tissue significantly increased final portal pressure (16). Our findings confirmed these previous findings. In addition, tissue volume was weakly but significantly correlated with released liver enzymes. Therefore, high tissue volume could be a risk factor for complications of autologous islet transplantation. Of note, we assessed the relationship between the duration of chronic pancreatitis versus islet yields and tissue vol umes to explore the optimal timing for autologous islet transplantation. However there were no correlations between the duration of chronic pancreatitis versus islet yields (R = 0.015, p = 0.94) and tissue volumes (R = 0.128, p = 0.541).

Next, we compared the complication group to the noncomplication group to clarify the characteristics of complication cases. The complication group had signifi cantly higher tissue volume and high maximum, final, and delta portal pressures. It seems reasonable to believe that high tissue volume causes high portal pressure, which results in complications. In addition, the complication group had a significantly higher body mass index and higher islet yield. Recently, we demonstrated that a high body mass index was associated with high islet yield and high tissue volume in autologous islet transplantation (19). Thus, high body mass index should be considered a risk factor for complications of autologous islet transplantation due to high tissue volume. On the other hand, high body mass index is also associated with high islet yield. Indeed, the complication group had significantly higher islet yield. However, only 25% of patients achieved insulin independence in the complication group, even though the transplanted islet yield was significantly higher than in the noncomplication group. In addition, when patients had portal thrombosis, none of three patients achieved insulin independence, even though all received >480,000 IEQ. In sharp contrast, when patients received >480,000 IEQ in the noncomplication group, 5 out of 7 patients (71%) achieved insu lin independence (p < 0.04, complication group vs. noncomplication group). This result suggests that com plications have a negative impact on islet function. Therefore, it seems reasonable to perform islet purification when the tissue volume is large for autologous islet transplantation. The University of Minnesota group indicated that it performs islet purification when tissue vol ume is >20 ml (16). However, in this study, the average tissue volume of the complication group was 16.9 ml. According to our data, currently we perform islet purification when tissue volume is >15 ml.

Finally, we analyzed the effect of islet purification on islet characteristics and clinical outcomes to identify the potential negative impact of islet purification. Since islet purification was performed based on tissue volume, the purification group had significantly higher tissue volume and a higher islet yield. Importantly, even after purifica tion, the islet yield was still significantly higher in the purification group. In addition, the purification group had significantly higher purity and similar viability com pared with the nonpurification group. Therefore, islet purification should not have a negative impact on islet characteristics. Of note, we used the density-adjusted continuous density gradient purification (12,13). The University of Minnesota group also performs density adjustment for islet purification in both allogeneic and autologous islet transplantation (2). It seems that the density adjustment is important to maintain high islet yield after purification.

In this study, none of the patients experienced primary nonfunction. Therefore, autologous islet transplantation should lead to better glucose metabolism for all patients. The ratio of achieving insulin independence was higher in the purification group, even though the result was not statistically significant. Based on these findings, we consider performing islet purification when the tissue volume is >12 ml. Further large-scale studies are necessary to clarify the safety and efficacy of aggressive purification protocols for autologous islet transplantation. In addition, the relationship between the long-term graft functions versus amount of nonendocrine tissues is interesting because nonendocrine tissue should include pancreatic stem cells that might improve the long-term graft function. This is another important endpoint and current our research target.

In this study we did not perform static incubation, in vivo assay, or beta cell viability because we aimed to maximize the transplanted islet mass. However, beta cell viability needs only limited number of islets and provides useful information to predict clinical outcomes (5). Therefore, we plan to include beta-cell viability for autologous islet transplantation.

In conclusion, high tissue volume was associated with high portal pressure and complications in autologous islet transplantation. Islet purification effectively reduced the tissue volume and had no negative impact on islet characteristics. Therefore, islet purification can reduce the risk of complications and may improve clini cal outcomes for autologous islet transplantation when the tissue volume is large.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was partially sup ported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1R21DK090513-01) (to S.M.) and the All Saints Health Foundation, Fort Worth, TX. The authors thank Ms. Cynthia Orticio for editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad SA, Lowy AM, Wray CJ, D'Alessio D, Choe KA, James LE, Gelrud A, Matthews JB, Rilo HL. Factors associated with insulin and narcotic independence after islet autotransplantation in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2005;201:680–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.06.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anazawa T, Matsumoto S, Yonekawa Y, Loganathan G, Wilhelm JJ, Soltani SM, Papas KK, Sutherland DE, Hering BJ, Balamurugan AN. Prediction of pancreatic tissue densities by an analytical test gradient system before purification maximizes human islet recovery for islet autotransplantation/allotransplantation. Transplantation. 2011;91:508–514. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182066ecb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CITR Research Group 2007 update on allogenic islet transplantation from the Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry (CITR). Cell Transplant. 2009;18:753–767. doi: 10.3727/096368909X470874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farney AC, Najarian JS, Nakhleh RE, Lloveras G, Field MJ, Gores PF, Sutherland DE. Autotransplantation of dispersed pancreatic islet tissue combined with total or near-total pancreatectomy for treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Surgery. 1991;110:427–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ichii H, Inverardi L, Pileggi A, Molano RD, Cabrera O, Caicedo A, Messinger S, Kuroda Y, Berggren PO, Ricordi C. A novel method for the assessment of cellular composition and beta-cell viability in human islet preparations. Am. J. Transplant. 2005;5:1635–1645. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latif ZA, Novel J, Alejandro R. A simple method of staining fresh and cultured islets. Transplantation. 1988;45:827–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsumoto S. Autologous islet cell transplantation to prevent surgical diabetes. J. Diabetes. 2011;3:328–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-0407.2011.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto S. Islet cell transplantation for type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes. 2010;2:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-0407.2009.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsumoto S, Noguchi H, Shimoda M, Ikemoto T, Naziruddin B, Jackson A, Tamura Y, Olsen G, Fujita Y, Chujo D, Takita M, Kobayashi N, Onaca N, Levy M. Seven consecutive successful clinical islet isolations with pancreatic ductal injection. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:291–297. doi: 10.3727/096368909X481773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumoto S, Qualley S, Goel S, Hagman D, Sweet I, Poitout V, Strong DM, Robertson RP, Reems J. Effect of the two-layer (University of Wisconsin solution-perfluorochemical plus O2) method of pancreas preserva tion on human islet isolation, as assessed by the Edmonton isolation protocol. Transplantation. 2002;74:1414–1419. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200211270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumoto S, Rigley TH, Qualley SA, Kuroda Y, Reems JA, Stevens RB. Efficacy of the oxygen-charged static two-layer method for short-term pancreas preservation and islet isolation from nonhuman primate and human pancreata. Cell Transplant. 2002;11:769–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsumoto S, Takita M, Chaussabel D, Noguchi H, Shimoda M, Sugimoto K, Itoh T, Chujo D, SoRelle AJ, Onaca N, Naziruddin B, Levy MF. Improving efficacy of clinical islet transplantation with iodixanol based islet purification, thymoglobulin induction and blockage of IL-1 beta and TNF-alpha. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:1641–1647. doi: 10.3727/096368910X564058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noguchi H, Ikemoto T, Naziruddin B, Jackson A, Shimoda M, Fujita Y, Chujo D, Takita M, Kobayashi N, Onaca N, Levy MF, Matsumoto S. Iodixanol-controlled density gradient during islet purification improves recovery rate in human islet isolation. Transplantation. 2009;87:1629–1635. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a5515c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricordi C, Lacy PE, Scharp DW. Automated islet isolation from human pancreas. Diabetes. 1989;38(Suppl 1):140–142. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.1.s140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez Rilo HL, Ahmad SA, D'Alessio D, Iwanaga Y, Kim J, Choe KA, Moulton JS, Martin J, Pennington LJ, Soldano DA, Biliter J, Martin SP, Ulrich CD, Somogyi L, Welge J, Matthews JB, Lowy AM. Total pancreatectomy and autologous islet cell transplantation as a means to treat severe chronic pancreatitis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2003;7:978–989. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutherland DE, Gruessner AC, Carlson AM, Blondet JJ, Balamurugan AN, Reigstad KF, Beilman GJ, Bellin MD, Hering BJ. Islet autotransplant outcomes after total pancreatectomy: a contrast to islet allograft outcomes. Transplantation. 2008;86:1799–1802. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31819143ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takita M, Matsumoto S, Noguchi H, Shimoda M, Chujo D, Sugimoto K, Itoh T, Lamont JP, Lara LF, Onaca N, Naziruddin B, Klintmalm GB, Levy MF. One hundred human islet isolation at Baylor Research Institute. Proc. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. 2010;23:341–348. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2010.11928648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takita M, Naziruddin B, Matsumoto S, Noguchi H, Shimoda M, Chujo D, Itoh T, Sugimoto K, Onaca N, Lamont JP, Lara LF, Levy MF. Variables associated with islet yield in autologous islet transplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Proc. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. 2010;23:115–120. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2010.11928597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takita M, Naziruddin B, Matsumoto S, Noguchi H, Shimoda M, Chujo D, Itoh T, Sugimoto K, Tamura Y, Olsen GS, Onaca N, Lamont JP, Lara LF, Levy MF. Body mass index reflects islet isolation outcome in islet autotransplantation for patients with chronic pancreatitis. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:313–322. doi: 10.3727/096368910X514611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White SA, London NJ, Johnson PR, Davies JE, Pollard C, Contractor HH, Hughes DP, Robertson GS, Musto PP, Dennison AR. The risks of total pancreatectomy and splenic islet autotransplantation. Cell Transplant. 2000;9:19–24. doi: 10.1177/096368970000900103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]