Abstract

Mn-based nanoparticles (NPs) have emerged as new class of probes for magnetic resonance imaging due to the impressive contrast ability. However, the reported Mn-based NPs possess low relaxivity and there are no immunotoxicity data regarding Mn-based NPs as contrast agents. Here, we demonstrate the ultrahigh relaxivity of water protons of 8.26 mM−1s−1 from the Mn3O4 NPs synthesized by a simple and green technique, which is twice higher than that of commercial gadolinium (Gd)-based contrast agents (4.11 mM−1s−1) and the highest value reported to date for Mn-based NPs. We for the first time demonstrate these Mn3O4 NPs biocompatibilities both in vitro and in vivo are satisfactory based on systematical studies of the intrinsic toxicity including cell viability of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells, normal nasopharyngeal epithelium, apoptosis in cells and in vivo immunotoxicity. These findings pave the way for the practical clinical diagnosis of Mn based NPs as safe probes for in vivo imaging.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a routine diagnostic tool in modern clinical medicine. One of significant advantages of MRI is able to obtain three-dimensional tomographic information about anatomical details with high spatial resolution and soft tissue contrast in a non-invasive and real-time manner1,2,3,4,5. In order to compensate the innate low sensitivity, the positive or T1 contrast agents are employed to increase contrast between organs of interest and normal organs by accelerating the longitudinal relaxivity (r1) of water protons, which leading to a brightening of MR image6,7,8. The majority of T1 MRI contrast probes are currently based on gadolinium (Gd3+) in the form of paramagnetic chelates9,10,11. However, their uses are occasionally associated with nephrogenic system fibrosis (NSF), which suggests a need of finding alternatives12,13,14. Recently, nanoparticles (NPs) have been extensively used in biomedical application15,16,17,18,19. As MRI contrast agents, NPs with high relaxivity and low toxicity are most expected. Among all the candidates, Mn-based NPs are regarded as promising alternatives due to their lower intrinsic toxicity than that of Gd3+ and increasing attention in neuroscience research20,21,22. However, the development of Mn-based NPs is hindered by two bottlenecks. One is that the Mn-based NPs with high relaxivity have not been still achieved, e.g., the relaxivity of the reported Mn-based NPs is usually lower than that of the commercial Gd-based agents (4.11 mM−1s−1)23,24,25. Another is that there have not been any pre-clinical reports on in vitro and in vivo studies of toxicity of Mn-based NPs20,21,22,23,24,25. Nanotoxicity26, especially immunotoxicity27,28,29, has emerged as one of the critical issues to make NPs into practical clinical applications. Although the standardized assessments on immunotoxicity of NPs in biomedical products have not yet been established, it's essential to assess the immune response to the nanoparticles in the pre-clinical research30,31.

Here we synthesize the ligand-free Mn3O4 NPs by a simple and green laser-based technique, i.e., laser ablation in liquid (LAL)32,33,34,35,36,37,38. Our measurements indicate that the water proton relaxivity is 8.26 mM−1s−1 when adding the Mn3O4 NPs, which is twice higher than that of the commercial Gd-DTPA contrast agent (4.11 mM−1s−1) and the highest value reported to date for Mn-based NPs23,24,25. We also for the first time take systematically the in vitro and in vivo pre-clinical studies on the toxicity of the as-synthesized Mn3O4 NPs and the pharmacokinetics assays. All the measurements confirm that this Mn-based nanoprobe is safe in biocompatible due to lack of any potential toxicity. Therefore, these results demonstrate that the LAL-derived Mn3O4 NPs are strong candidates as effective and safe targeted probes for early tumor diagnosis, and superior to the commercial Gd-based contrast agents in terms of contrast enhancement with a satisfactory biocompatibility.

Results

Structure, morphology and component of Mn3O4 NPs

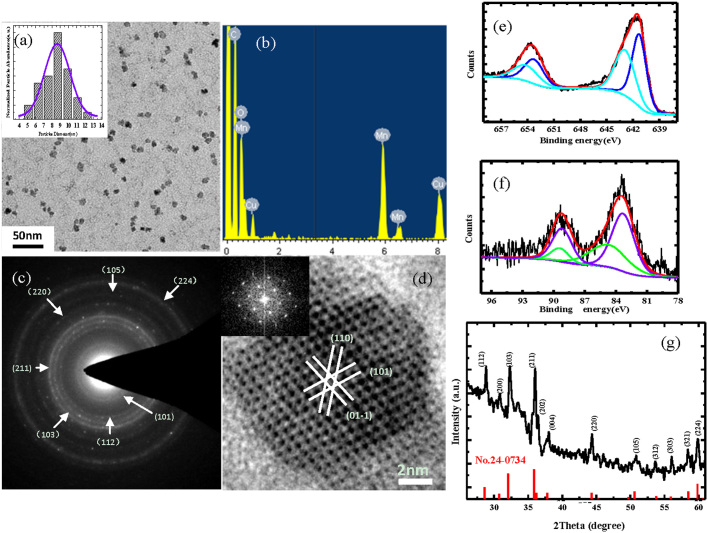

From Fig. 1a, we can see the uniform and dispersive NPs with a diameter of about 9 nm (calculated from about 200 nanoparticles). The energy dispersive spectrum (Fig. 1b) shows the products are composed of Mn and O elements, and the Cu and C peaks originate from the copper grid and amorphous carbon film support, respectively. The selected area electronic diffraction (Fig. 1c) reveals that these NPs are consistent with strong ring patterns of the tetragonal Mn3O4 structure. The high resolution TEM (Fig. 1d) also confirms this result. The XPS measurements are employed to analyze the Mn oxidation states so as to determine which chemical valence state is responsible for shortening relaxation time. From Fig. 1e, the binding energy of Mn 2p3/2 peaks components are 641.2 and 642.9 eV, which correspond exactly with the data reported respectively for Mn2+ and Mn4+ 39,40,41. The splitting of the Mn 3s doublets (Fig. 1f) are 5.8 and 4.6 eV, which are in agreement with the relative value of Mn2+ and Mn4+ valence states39,40,41. Therefore, XPS analyses show that the external layers of the products are consisted of Mn2+ and Mn4+. Note that Mn2+ has 5 unpaired electrons, which are more than other valence states of Mn ion. Fig. 1g shows the XRD pattern of the products. Clearly, all the peaks are indexed to Mn3O4 with the tetragonal structure (JCPDS no.24-0734) without metallic manganese or other oxide phase, which indicates that the as-synthesized Mn3O4 NPs are crystalline and of high purity.

Figure 1. Characterizations of structure, morphology and component of Mn3O4 NPs.

(a) TEM image of dispersive Mn3O4 NPs. The distribution histogram and its Gaussian fitting curve (inset) to demonstrate that the mean size of the sample is about 9nm. (b) EDS spectrum of Mn3O4 NPs. (c and d) The corresponding selected-area electron diffraction pattern and high resolution TEM image, the inset in (d) shows a fast Fourier transform analysis of individual Mn3O4 NPs. (e and f) XPS spectrum of Mn2p and Mn3s level. (g) XRD pattern of the as-synthesized Mn3O4 NPs.

In vitro and in vivo MR imaging

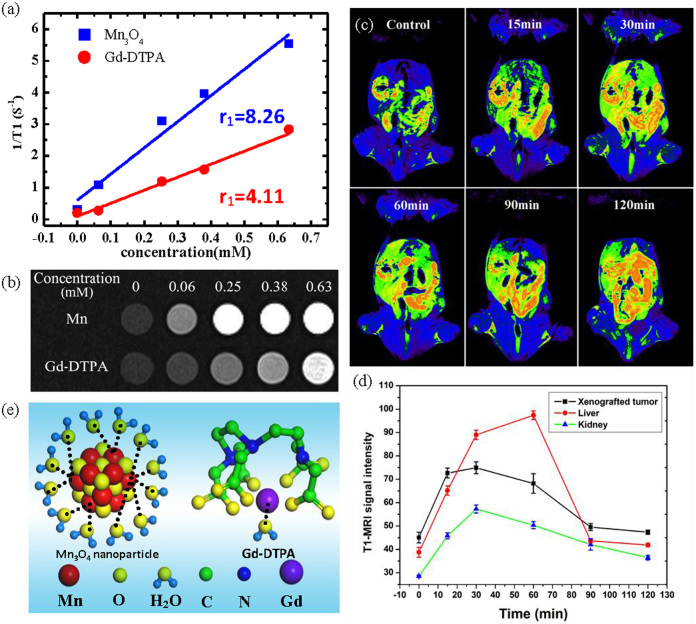

The MRI properties of the Mn3O4 NPs in water are characterized by a 3T MR scanner. The molar relaxivity (Fig. 2a) is obtained by measuring the relaxation rate of water protons with increasing concentrations of NPs, and is calculated to be 8.26 mM−1s−1. This value is twice higher than that of Gd-DTPA (4.11 mM−1s−1) and the highest value reported to date for Mn-based NPs (Table 1)23,24,42,43,44,45,46,47. These nanocrystals are also tested in PBS solution in order to simulate the culture medium. The relaxivity is calculated to be 6.79 mM−1s−1 (shown in Supplementary Fig. S2a). Meanwhile, the Mn3O4 NPs provide improved contrast enhancement compared to Gd-DTPA contrast agents from Fig. 2b.

Figure 2. In vitro and in vivo MR imaging.

(a) The relaxivity (r1) of Mn3O4 NPs and commercially Gd-DTPA detected by nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersion (NMRD). (b) T1-weighted phantom MRI of various concentrations of Mn3O4 NPs (upper row) and Gd-DTPA (lower row). (c) Representative dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI of a nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) CNE-2 xenografted tumor (white arrow), liver and kidney in Balb/c nude mice obtained at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120 min, respectively, after intravenous administration of Mn3O4 NPs (15 μmolkg−1). (d) Dynamic enhancement curve of xenografted tumor, liver and kidney. (e) Schematic illustration of interaction between contrast agent (Mn3O4 NPs (left side) and Gd-DTPA (right side)) and water.

Table 1. Comparison of relaxivity of reported Mn-based NPs.

| Materials* | Core element | r1(mM−1s−1) | Field(T) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMnO@mSiO2 | MnO | 0.99 | 11.7 | 23 |

| MnO@PEG-phospholipid | MnO | 0.11 | 11.7 | 23 |

| MnO@mSiO2 | MnO | 0.65 | 11.7 | 23 |

| MnO@dSiO2 | MnO | 0.08 | 11.7 | 23 |

| Mn3O4 nanospheres | Mn3O4 | 1.31 | 3 | 24 |

| Mn3O4 nanoplates | Mn3O4 | 2.06 | 3 | 24 |

| Mn3O4 nanocubes | Mn3O4 | 1.08 | 3 | 24 |

| MnO nanoplates | MnO | 5.5 | 3 | 42 |

| Mn3O4@SiO2 | Mn3O4 | 0.47 | 3 | 44 |

| WMON | MnO | 0.21 | 3 | 22 |

| HMnO | Mn3O4 | 1.42 | 3 | 22 |

| HSA-MNOP | MnO | 1.97 | 7 | 43 |

| Mn-NMOFs | MnO | 4 | 9.4 | 45 |

| MnO | MnO | 0.12 | 3 | 46 |

| Mn-MSNs | MnO(Mn3O4) | 2.28 | 3 | 47 |

| Mn3O4 | Mn3O4 | 8.26 | 3 | Our results |

*Materials annotations: HMnO@mSiO2 –mesoporous silica coated hollow MnO or Mn3O4 nanoparticles. MnO@PEG-phospholipid: PEG-phospholipid coated MnO nanoparticles. MnO@mSiO2: mesoporous silica-coated MnO nanoparticles. MnO@dSiO2: dense silica coated MnO nanoparticles. Mn3O4@SiO2: silica coated Mn3O4 nanoparticles. WMON: water-dispersible manganese oxide nanoparticles. HMON: hollow manganese oxide nanoparticles. HSA@MNOP: human albumin coated manganese oxide nanoparticles. Mn-NMOFs: manganese-containing nanoscale metal-oraganic frameworks. Mn-MSNs: dispersing manganese oxide nanparticles into mesopores of mesopourous silica nanoparticles.

To assess the in vivo MR imaging, the Mn3O4 NPs are intravenously administrated into Balb/c nude mice with nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) CNE-2 xenografted tumors. Dynamic contrast enhanced T1-weighted MRI of liver, kidney and xenografted tumor is obtained. As shown in Fig. 2c and d, the T1-weighted MR images clearly show a high contrast enhancement of the xenografted tumor (white arrow) after injecting the Mn3O4 NPs at 30 min. In addition, the corresponding kidney enhancement and grey-scale image are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3 and S4. Note that the administered concentration of Mn in our MRI assessment is 15 μmolkg−1, which is only 1/7-1/14 of standard clinical dose of Gd-DTPA (0.1–0.2 mmolkg−1)48. The same dose of Gd-DTPA is also injected (shown in Supplementary Fig. S5), the signal enhancement is about 23%, which is lower than that of as-synthesized Mn contrast agent (64%). Therefore, both the in vitro and in vivo investigations confirm that the Mn3O4 NPs are more effective than Gd-DTPA in T1-weighted images.

The longitudinal relaxivity is proportional to the hydration number of water (q) that coordinates to the unpaired electrons of contrast agents9. Referring to the commercially available clinical contrast agent Gd-DTPA, the ligand DTPA forms a sufficiently stable complex around the Gd3+ ion, and only one coordination site is open up for water ligation, however, the Mn2+ carries five unpaired electrons, which offer more free sites for water ligation and result in higher r19,49. Fig. 2e provides a schematic illustration of interaction between contrast agent (Mn3O4 NPs and Gd-DTPA) and water.

Evaluation of toxicity in vitro and in vivo

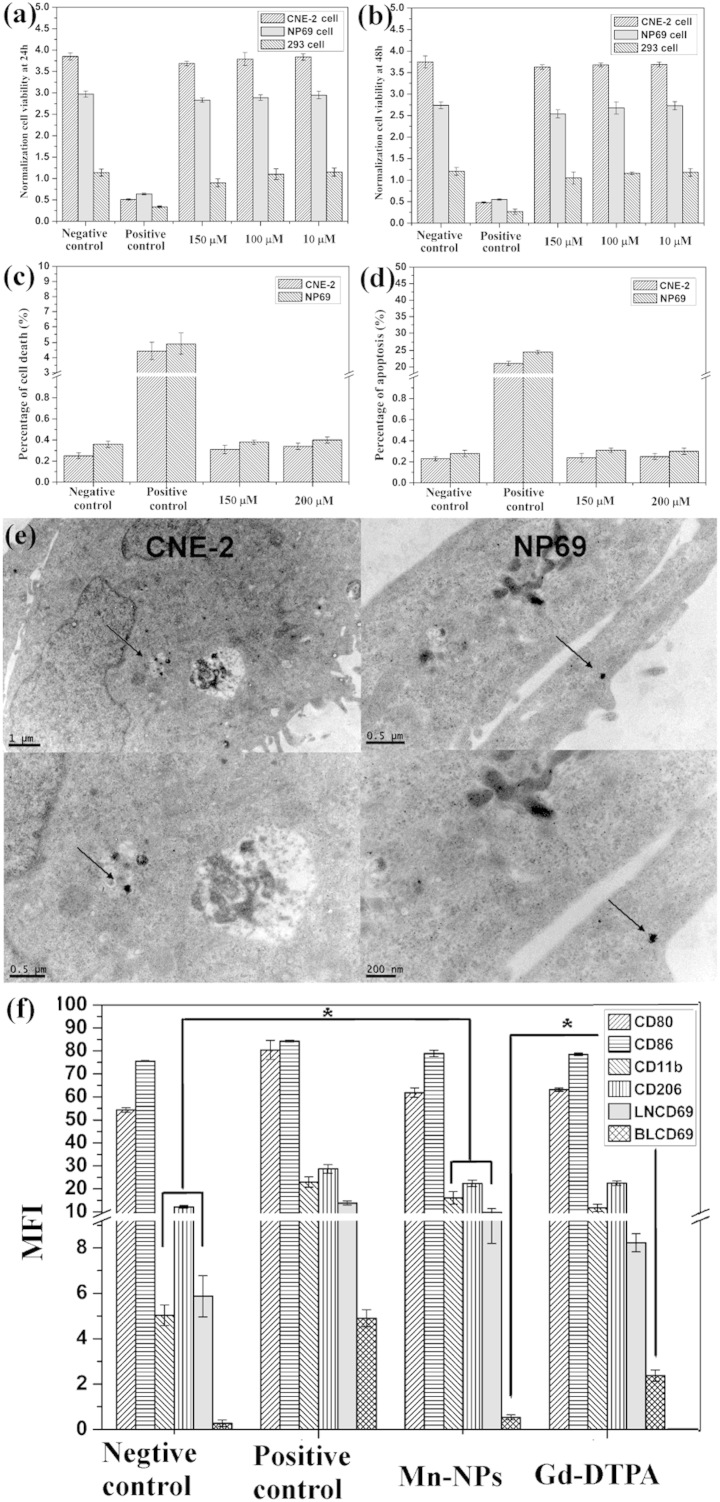

To evaluate the toxicity of the Mn3O4 NPs in vitro, cell viability of L929 cells, 293 cells, NP69 cells (normal nasopharyngeal epithelium) and CNE-2 (human nasopharyngeal carcinoma) cells is determined by [3-4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide succinate (MTT) assay at 24 and 48 h, respectively. Clearly, the Mn3O4 NPs do not significantly affect cell viability in Fig. 3a, b Supplementary Fig. S6, and the cytotoxicity of the Mn3O4 NPs is very negligible. In addition, death and apoptosis of NP69 cells and CNE-2 cells are evaluated by flow cytometry stained with Annexin-V/PI. Fig. 3c, d and Supplementary Fig. S7 confirm the results of MTT assay. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 3e, TEM images of CNE-2 cells and NP69 cells show that the nanoprobes are absorbed by cells at 24 h. These results thus demonstrate that our nanoprobes have no effects on cells survival.

Figure 3. Toxicity assay of Mn3O4 NPs in vitro and in vivo.

(a–b) The data of cell viability on CNE-2, NP69 and 293 cells incubated with different concentrations (150 μM, 100 μM, and 10 μM) of the Mn3O4 NPs for 24 and 48 h. (c–d) Cell death and Apoptosis rate of CNE-2 and NP69 cells were measured by flow cytometry at 48 h after incubation of PBS, LPS, Mn3O4 NPs (150 μM and 200 μM). Cells were stained by annexin V and PI. (e) Cells absorption data of the Mn3O4 NPs. TEM images of CNE-2 and NP69 at 12 h after incubation with the Mn3O4 NPs (100 mmol/L). (f) Immunotoxicity assay in vivo. CD80, CD86, CD11b and CD206 expression of monocytes/macrophages in peripheral blood, as well as CD69 cytokine of adaptive immune in lymphocyte cells of peripheral blood (BL) and lymph nodes (LN). * P < 0.05 compared with Gd-DTPA group.

To further investigate the toxicity of the Mn3O4 NPs in vivo, the immunotoxicity are evaluated in Balb/c mice. In brief, we determine the typical cytokines of innate immune including CD206, CD11b, and CD80/CD86 of monocytes/macrophages in peripheral blood, as well as CD69 cytokine of adaptive immune in lymphocyte cells of peripheral blood and lymph nodes. The results are showed in Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. S8. There is significant difference between NPs and positive control groups (LPS), which indicating that the measurement is credible. Though there is statistical difference between Mn3O4 NPs and the negative control groups (PBS) on the expression levels of CD11b, CD206 and LNCD69, which indicates that our nanoprobes do slightly stimulate the immune response system, no obvious difference is found between the Mn3O4 NPs and Gd-DTPA groups. Besides, the blood CD69 of the Mn3O4 NPs group is decreased slightly compared to that of the Gd-DTPA group, which confirming that the as-synthesized Mn-based NPs are as safe as Gd-DTPA. Because Gd-DTPA is the commercial and widely used clinical contrast agent, Mn3O4 NPs might exhibit a little immunotoxicity, but the immune response can be acceptable by body in vivo.

Pharmacokinetics assays including half-time, biodistribution, and excretion

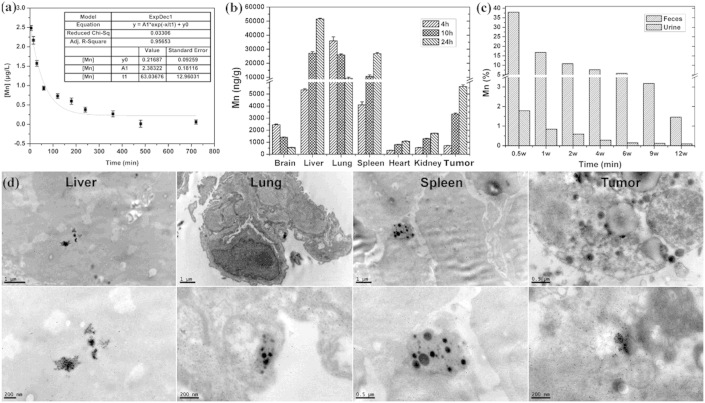

Assessing the toxicity of nanobased biomedicine is involved with physicochemical characteristics. Thus, we first measure the stability of our nanoprobes in blood. The half-life of the Mn3O4 NPs is 63.04 (±12.96) min in blood (Fig. 4a), which is much longer than that of Gd-DTPA (20 min)48. The longer half-life shows the favorable stability and low blood toxicity in vivo. Importantly, it can effectively improve the accumulation of nanoprobes in tumor tissue during circulation and the sensitivity of MR imaging.

Figure 4. Pharmacokinetic characterizations of Mn3O4 NPs.

(a) Half-life in the blood is determined by ICP-MS, and regularly measured the concentrations of Mn in blood samples (n = 3). (b) Concentrations of Gd were quantified in the brain, liver, lung, spleen, heart, kidney, and the tumor tissue (n = 3) at 4, 10 and 24 h, respectively, after intravenous injection (15 μmol/kg). (c) Excretion of Mn is assayed in feces and urine of mice every week (n = 3) up to 12 weeks. (d) The biodistribution at the subcellular lever. TEM images of liver, lung, spleen and xenografted tumors in nude mice at 4 h after intravenous administration of the Mn3O4 NPs (15 μmol/kg).

To further investigate the biodistribution and excretion of the Mn3O4 NPs, the quantitative analysis on Mn concentration is measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) in typical organs, xenografted tumor tissues, feces and urine of mice. From Fig. 4b, we can see that our nanoprobes accumulate gradually in the lung, liver, spleen, and tumor tissue, but few are found in the brain, heart, and kidney. The exact concentrations of Mn in different organs are listed in the Supplementary Table S1. Interestingly, the Mn3O4 NPs accumulate increasingly in tumor tissues via the repeated blood circulation, which suggesting that it is a potential tumor-targeting nanoprobe. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 4c, about 50% of Mn is excreted via the hepatobiliary transport system within 1.5 weeks. Though hepatobiliary excretion is a slow process, it can still effectively decrease the occurrence of toxicity due to the accumulation of NPs. Importantly, the biodistribution at the subcellular level is observed by TEM, Fig. 4d shows our nanoprobes are mainly localized in the macrophages in the liver, lung, and spleen, as well as in the cytoplasm of epithelial cells in the xenografted tumor tissue. Since the as-synthesized NPs are dispersed inside the tissues with little aggregation, which leading to gradual excretion and minimal cell toxicity. In addition, no abnormalities are found in histological sections of the main organ including brain, heart, kidney, liver, lung, and spleen (Supplementary Fig. S9), which suggest that the cellular integrity and tissue morphology are not affected by our nanoprobes.

Discussion

The reason that the r1 value of the Mn3O4 NP synthesized by LAL is higher than that of other Mn-based NPs is still unclear. We suggest that the distance between water and nanoprobes can be one of the influence factors. The T1 relaxation of water protons is affected by Mn ion via dipolar mechanism, which is a multifaceted phenomenon. Water in close proximity to ion is relaxed and paramagnetic T1 relaxation enhancement is a spin-lattice effect, which requires a direct contact between surface Mn ion and water9,10,39. Based on the Solomon-Bloembergen-Morgan (SBM) theory50,51,52,53, a classical existing theory of interpreting relaxation of water protons in the present of contrast agent, the relaxivity has a 1/d6 dependence on the distance (d) between contrast agents and water proton, which can be simplified as: r1∝d−6. So, in this case, the shorter the distance between external Mn ion and water proton is, the higher relaxivity is. Additionally, the surface of the LAL-derived NPs is not blocked by any chemical ligands or residues of any reducing agents, which reduce the distance between Mn ion and water proton. This hypothesis has been verified by changing deionized water into 5 mM SDS solution when ablating the target. The FTIR spectrum exhibits that SDS has coated the surface of Mn3O4 nanocrystals54,55, the corresponding relaxivity is dropped to be 1.75 mM−1s−1 (shown in Supplementary Fig. S3b–3c), which is much lower than the relaxivity of products synthesized in deionzed water (8.26 mM−1s−1). Therefore, clean surface remains when LAL in deionized water, which is likely to result in higher r1.

In summary, we have synthesized the Mn3O4 NPs with the ultrahigh relaxivity of 8.26 mM−1s−1 by a simple and green laser-based technique. We further demonstrate that these Mn-based NPs are safe and effective targeted probes for in vivo imaging based on the in vitro and in vivo assessments of biocompatibility, especially the evidence of immunotoxicity. These findings break through the bottleneck in the application of Mn-based NPs for MRI and pave the way for the practical clinical diagnosis of Mn-based NPs as safe probes for in vivo imaging.

Methods

We stated that all the experiments have been approved by the State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China of China in this study.

Mn3O4 NPs synthesis

The details of laser ablation in liquids have been reported in our previous works33,34. In this case, a manganese target (99.99% purity) is firstly fixed on the bottom, and then the deionized water is poured into the chamber until the target in covered by 8 mm. Then, a second harmonic produced by a Q-switch Nd: YAG laser device with a wavelength of 10 Hz, and laser pulse power of 70 mJ, is focused onto the surface of manganese target. The spot sized is 1 mm in diameter and the whole ablation lasts for 30 min. The experimental setup is Supplementary shown in Fig. S1. As a result, the brown colloid solution is synthesized and collected into a cuvette. After 24 hours, the upper clear liquid is collected for further measurement.

Products characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed with a Rigaku D/Max-IIIA X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å, 40 kV, 20 mA) at a scanning rate of 1° s−1, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was carried out with a JEOL JEM-2010HR instrument at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV, equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS). Sample was ultrasounded for a few minutes and then one drop pipette onto a carbon support film on a copper grid. These techniques are used to identify the structure and morphology of as-synthesized samples. XPS (ESCAlab250) is employed to analyze the composition of the surface of samples. Inductively coupled plasma-atomic (ICP) emission spectrometry using a ThermoFisher iCAP6500Duo has been employed to analyze the concentration of Mn, with an incident power of 1150 W, a plasma gas flow of 14 L/min, and an atomization gas flow of 0.6 L/min.

MRI in vitro

Various samples of Mn concentrations (from 0.06 to 0.63 mM) are in 1.5 ml EP tubes, and subject to T1-weighted phantom MRI by 3.0 T clinical scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). The concentration of Mn is obtained by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES, Spectro ciros vision, Spectro, Germany). The sequences are TSE T1 axial (5% dist. Factor, slice thickness 2.0 mm, FOV 64 mm, TE 12 ms, TR 600 ms, six averages). All data are analyzed by picture archiving and communications system (PACS).

MRI in vivo

Balb/c nude mice with NPC CNE2 xenografted tomrs are induced anesthesia by intraperitoneal injection of 0.1 mebumalnatrium (10 μL per g weight), than injected with 15 μmol/kg of the Mn3O4 NPs by the tail vein, scanned on a 3.0 T Siemens Trio MRI scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) using a surface coil with 3 inch in diameter. The control group is the uninjected mice. T1-weighted images are obtained at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min after intravenous administration in the axial orientations. The sequences are the same as the MRI in vitro. To be not biased toward aberrantly enhanced regions, the entire tumor is generated the normalized histograms of signal intensity.

Cytotoxicity assay

The Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells in logarithmic growth period are incubated with different concentrations of the Mn3O4 NPs (150 μM, 100 μM, and 10 μM) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 in 96-well plates, at 37°C, 5% CO2, treated only with culture media as negative control, treated with 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as positive control, all groups are cultured for 24 and 48 h post-treatment, respectively. Then, added 20 μL of MTT for another 4 h of incubation, replaced culture media with 100 μL DMSO for 10 min. The samples are measured by a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, USA) at 490 nm.

Apoptosis assay

The NP69 cells and CNE-2 cells in 6-well plants are incubated with PBS (negative control), LPS (positive control) and the Mn3O4 NPs (150 μM and 200 μM) for 48 h, washed twice in cold PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) by gentle shaking, then resuspended cell pellet with 200 μL Binding Buffer (1×) at 4 × 105 cells/ml, added 5 μL Annexin V-FITC (eBioscience) into 195 μL cell suspension, mixed and incubated for 10 min at room temperature, washed cells twice in 200 μL Binding Buffer (1×), and resuspended in 190 μL Binding buffer (1×), then added 10 μL PI (Propidium Iodide) (20 μg/mL), the samples are measured on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Immunotoxicity assay in vivo

Male Balb/c mice are 6–8 weeks old, 20 mice are divided into 4 groups at random: PBS (100 μL, Negative control), Gd-DTPA (15 μmol/kg), LPS (100 μL, Positive control), the Mn3O4 NPs (15 μmol/kg). Peripheral blood or lymphocytes are measured after tail vein administration at 48 h by flow cytometry, stained with anti-mouse CD3-PE, anti-mouse CD11b-FITC, anti-mouse CD80/CD86-PE, anti-mouse CD69-FITC (Becton Dickinson PharMingen), and anti-mouse F4/80 antigen APC, anti-mouse CD206-PE (eBioscience).

Pharmacokinetic characterizations

Concentrations of Mn are measured by ICP-MS (Thermo Instrument System Inc. USA) for all the samples of pharmacokinetics.

Half-life in the blood

The half-life in the blood is determined by 30 clean Kunming white mice (50% males and 50% females). Blood is obtained by the tail veins at 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 180, 240, 360, 480, and 720 min, respectively, after tail vein administration of the Mn3O4 NPs (15 μmol/kg).

Biodistribution at the organ and subcellular level

At the organ lever, brain, liver, lung, spleen, heart, kidney, and tumor are collected at 4, 10, and 24 h, respectively, after nanoprobes injection (15 μmol/kg). At the subcellular level, liver, lung, spleen, and tumor are obtained at 4 h after injection. Samples were measured by TEM.

Excretion of the nanoprobes

Feces and urine of mice are collected every week (n = 3) for 12 weeks after injection (15 μmol/kg).

Author Contributions

J.X., X.M.T., C.Y., P.L., N.Q.L., Y.L., H.B.L., D.H.C. and C.X.W.: experimental work and data analysis. L.L. and G.W.Y.: project planning, data analysis.

Supplementary Material

Ultrahigh relaxivity and safe probes of manganese oxide nanoparticles for in vivo imaging

Acknowledgments

The National Basic Research Program of China (2014CB931700), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91233203, 11004253, 81071207 and 81271622), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (201104359), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (S2011040001673) and the State Key Laboratory of Optoelectronic Materials and Technologies supported this work.

References

- Belliveau J. W. et al. Functional mapping of the human visual cortex by magnetic resonance imaging. Science 254, 716–719 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong K. K. et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity during primary sensory stimulation. P. Natl. Acad. Sci 89, 5675–5679 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno M. I. et al. Borders of multiple visual areas in humans revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Science 268, 889–893 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissleder R. & Pittet M. J. Imaging in the era of molecular oncology. Nature 452, 580–9 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie A. Multimodality Imaging Probes: Design and Challenges. Chem. Rev. 110, 3146–3195 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. Il et al. Nonblinking and Nonbleaching Upconverting Nanoparticles as an Optical Imaging Nanoprobe and T1 Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agent. Adv. Mater. 21, 4467–4471 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Ananta J. S. et al. Geometrical confinement of gadolinium-based contrast agents in nanoporous particles enhances T1 contrast. Nature 5, 815–821 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z., Thorek D. L. J. & Tsourkas A. Gadolinium-Conjugated Dendrimer Nanoclusters as a Tumor-Targeted T1 Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 346–350 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caravan P. Strategies for increasing the sensitivity of gadolinium based MRI contrast agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 35, 512–523 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caravan P., Ellison J. J., McMurry T. J. & Lauffer R. B. Gadolinium(III) Chelates as MRI Contrast Agents: Structure, Dynamics, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 99, 2293–2352 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauffer R. E. Paramagnetic Metal Complexes as Water Proton Relaxation Agents for NMR Imaging: Theory and Design. Chem. Rev. 87, 901–27 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Idée J.-M., Port M., Dencausse A., Lancelot E. & Corot C. Involvement of Gadolinium Chelates in the Mechanism of Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis: An Update. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 47, 855–869 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer R. D. et al. In an animal model nephrogenic systemic fibrosis cannot be induced by intraperitoneal injection of high-dose gadolinium based contrast agents. Eur. J. Radiol. 81, 2562–2567 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen H. et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and gadolinium-based contrast media: updated ESUR Contrast Medium Safety Committee guidelines. Eur. Radiol. 23, 307–318 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na, H. Bin, Song I. C. & Hyeon T. Inorganic Nanoparticles for MRI Contrast Agents. Adv. Mater. 21, 2133–2148 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Jun Y., Seo J. & Cheon J. Nanoscaling Laws of Magnetic Nanoparticles and Their Applicabilities in Biomedical Sciences. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 179–189 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao R. et al. Synthesis, Functionalization, and Biomedical Applications of Multifunctional Magnetic Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 22, 2729–2742 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanh N. T. K. & Green L. A. W. Functionalisation of nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Nano Today 5, 213–230 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Byrappa K., Ohara S. & Adschiri T. Nanoparticles synthesis using supercritical fluid technology – towards biomedical applications. Adv. Drug. Deliver. Rev. 60, 299–327 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X., Wadghiri Y. Z., Sanes D. H. & Turnbull D. H. In vivo auditory brain mapping in mice with Mn-enhanced MRI. Nat. Neurosci 8, 961–8 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na, H. Bin et al. Development of a T1 contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging using MnO nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 5397–401 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. et al. Hollow manganese oxide nanoparticles as multifunctional agents for magnetic resonance imaging and drug delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 321–4 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. et al. Mesoporous silica-coated hollow manganese oxide nanoparticles as positive T1 contrast agents for labeling and MRI tracking of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 2955–61 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.-C., Khu N.-H. & Yeh C.-S. The characteristics of sub 10 nm manganese oxide T1 contrast agents of different nanostructured morphologies. Biomaterials 31, 4073–8 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F. & Zhao Y. S. Inorganic nanoparticle-based T1 and T1/T2 magnetic resonance contrast probes. Nanoscale 4, 6235–6243 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H. C. & Chan W. C. W. Nanotoxicity: the growing need for in vivo study. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 18, 565–571 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrovolskaia M. A. & McNeil S. E. Immunological properties of engineered nanomaterials. Nat. Nano 2, 469–478 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrovolskaia M. A., Germolec D. R. & Weaver J. L. Evaluation of nanoparticle immunotoxicity. Nat. Nano 4, 411–414 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrand A. M. et al. Metal-based nanoparticles and their toxicity assessment. Wires. Nanomed. Nanobi. 2, 544–568 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y. et al. The properties of Gd2O3-assembled silica nanocomposite targeted nanoprobes and their application in MRI. Biomaterials 33, 6438–46 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen Z. & Xie J. Development of Manganese-Based Nanoparticles as Contrast Probes for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Theranostics 2, 45–54 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G. W. Laser Ablation in Liquids: Principles and Applications in the Preparation of Nanomaterials. (Pan Stanford publishing, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Cao Y. L., Wang C. X., Chen X. Y. & Yang G. W. Micro- and Nanocubes of Carbon with C 8 -like and Blue Luminescence 2008. Nano Lett. 8, 2570–2575 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Cui H., Wang C. X. & Yang G. W. From nanocrystal synthesis to functional nanostructure fabrication: laser ablation in liquid. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 3942–3952 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G. Laser ablation in liquids: Applications in the synthesis of nanocrystals. Prog. Mater. Sci. 52, 648–698 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H. et al. Nanomaterials via Laser Ablation/Irradiation in Liquid: A Review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 1333–1353 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J., Liu P., Liang Y., Li H. B. & Yang G. W. Porous tungsten oxide nanoflakes for highly alcohol sensitive performance. Nanoscale 4, 7078–7083 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Liang C., Tian Z., Zhang S. & Shao G. Spontaneous Growth and Chemical Reduction Ability of Ge Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 3, 1741 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Di Castro V. & Polzonetti G. XPS study of MnO oxidation. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phen. 48, 117–123 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Ardizzone S., Bianchi C. L. & Tirelli D. Mn3O4 and γ-MnOOH powders, preparation, phase composition and XPS characterisation. Colloid Surface A 134, 305–312 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. J. et al. Novel catalytic effects of Mn3O4 for all vanadium redox flow batteries. Chem. Commun. 48, 5455–5457 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M. et al. Large-Scale Synthesis of Ultrathin Manganese Oxide Nanoplates and Their Applications to T1 MRI Contrast Agents. Chem. Mater. 23, 3318–3324 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. et al. HSA coated MnO nanoparticles with prominent MRI contrast for tumor imaging. Chem. Commun. 46, 6684–6 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. et al. Silica-Coated Manganese Oxide Nanoparticles as a Platform for Targeted Magnetic Resonance and Fluorescence Imaging of Cancer Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 1733–1741 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K. M. L., Rieter W. J. & Lin W. Manganese-Based Nanoscale Metal−Organic Frameworks for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14358–9 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilad A. A. et al. MR tracking of transplanted cells with “positive contrast” using manganese oxide nanoparticles. Magn. Reson. Med. 60, 1–7 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. et al. Structure-property relationships in manganese oxide--mesoporous silica nanoparticles used for T1-weighted MRI and simultaneous anti-cancer drug delivery. Biomaterials 33, 2388–98 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinmann H., Brasch R., Press W. & Wesbey G. Characteristics of gadolinium-DTPA complex: a potential NMR contrast agent. Am. J. Roentgenol. 142, 619–624 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo N. et al. High longitudinal relaxivity of ultra-small gadolinium oxide prepared by microsecond laser ablation in diethylene glycol. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 164306 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Bloembergen N. & Morgan L. O. Proton Relaxation Times in Paramagnetic Solutions. Effects of Electron Spin Relaxation. J. Chem. Phys. 34, 842 (1961). [Google Scholar]

- Solomon I. Relaxation Processes in a System of Two Spins. Phys. Rev. 99, 559–565 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- Bloembergen N. Proton Relaxation Times in Paramagnetic Solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 27, 572–573 (1957). [Google Scholar]

- L. Villaraza A. J., Bumb A. & Brechbiel M. W. Macromolecules, Dendrimers, and Nanomaterials in Magnetic Resonance Imaging: The Interplay between Size, Function, and Pharmacokinetics. Chem. Rev. 110, 2921–2959 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M. K. et al. Dumbbell shaped nickel nanocrystals synthesized by a laser induced fragmentation method. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 11074–11079 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. Z., Xu C. K., Wang G. G., Liu Y. K. & Zheng C. L. Preparation of Smooth Single-Crystal Mn3O4 Nanowires. Adv. Mater. 11, 837–840 (2002) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Ultrahigh relaxivity and safe probes of manganese oxide nanoparticles for in vivo imaging