Abstract

Background

Data on use of endoscopic hemostasis performed during colonoscopy for hematochezia are primarily derived from expert opinion and case series from tertiary care settings.

Objective

To characterize patients with hematochezia who underwent in-patient colonoscopy and compare those who received endoscopic hemostasis with those who did not receive endoscopic hemostasis.

Design

Retrospective analysis

Setting

Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI) National Endoscopic Database 2002 – 2008

Patients

Adults with hematochezia

Interventions

None

Main Outcome Measurements

Demographics, co-morbidity, practice setting, adverse events, and colonoscopy procedural characteristics and findings.

Results

We identified 3,151 persons who underwent in-patient colonoscopy for hematochezia. Endoscopic hemostasis was performed in 144 patients (4.6%). Of those who received endoscopic hemostasis, the majority were male (60.3%), White (83.3%), older (mean age 70.9 ± 12.3 years), had a low risk ASA Score (53.9%), and underwent colonoscopy in a community setting (67.4%). The hemostasis-receiving cohort was significantly more likely to be White (83.3% vs. 71.0%, p=0.02), have more co-morbidities (ASA Score III and IV 46.2% vs. 36.0%, p=0.04), and have the cecum reached (95.8% vs. 87.7%, p=0.003). Those receiving hemostasis were significantly more likely to have an endoscopic diagnosis of AVM’s (32.6% vs. 2.6%) p=0.0001or solitary ulcer (8.3% vs. 2.1%), p<0.0001.

Limitations

Retrospective database analysis.

Conclusions

Less than five percent of persons presenting with hematochezia and undergoing inpatient colonoscopy received endoscopic hemostasis. These findings differ from published tertiary care setting data. These data provide new insights on in-patient colonoscopy performed primarily in a community practice setting for patients with hematochezia.

Introduction

Acute, overt lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), manifested as hematochezia, often leads to hospital admission [1–5]. Common causes of acute LGIB include colonic diverticulosis, vascular ectasias, ischemic colitis, colorectal polyps and neoplasms, inflammatory bowel disease, anorectal conditions, and postpolypectomy bleeding [2, 4–5].

Similar to esophagogastroduodenoscopy for acute upper GI bleeding, colonoscopy is the preferred initial examination in the diagnosis and possible therapeutic intervention of acute hematochezia [1–7]. However, in contrast to acute upper GI bleeding, there are only limited population-based data on LGIB colonoscopy findings and endoscopic therapies. Using CORI data, we recently characterized individuals with hematochezia undergoing colonoscopy in primarily community practice [8]. Published data on endoscopic hemostasis during colonoscopy for LGIB are derived almost exclusively from expert clinical experience at tertiary care hospitals [1]. There is limited information characterizing LGIB patients evaluated by colonoscopy and endotherapies used in community practice settings, which comprise the majority of endoscopic practices in the United States. The aim of this study was to describe and compare patients with hematochezia who underwent colonoscopy and compare those who received with those who did not receive endoscopic hemostasis using population-based data, primarily from community practice. In addition, we performed age-stratified analyses comparing older patients (≥60 years) presenting with acute LGIB to younger LGIB patients (18 to 59 years).

Methods

Data Source – Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative – National Endoscopic Database

We used the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI) for this population-based study. CORI was established in 1995, to study utilization and outcomes of endoscopy in diverse gastroenterology practice settings in the United States. All participating CORI endoscopy sites use a standardized computerized report generator to create all endoscopic reports and comply with CORI quality control requirements. The sites’ data files are transmitted electronically on a weekly basis to a central data repository – the National Endoscopic Database (NED) located in Portland, OR, USA.

The data that is transmitted from the local site to the National Endoscopic Database does not contain most patient or provider identifiers and qualifies as a Limited Data Set under 45 C.F.R. Section 164.514(e)(2). After completion of quality control checks, data from all sites are merged in the data repository for analysis. The data repository is checked for anomalies on a daily basis and endoscopy procedure counts are monitored on a weekly basis for atypical activity. Any noted unusual activity prompts follow-up contact by CORI staff. Multiple studies on a variety of endoscopy-related topics that have used CORI data have resulted in peer-reviewed publications [8–15]. The CORI national database was given approval by the IRB of the Oregon Health & Science University (eIRB #733) in October 2011. This present study used a limited dataset of CORI and was therefore exempted from further IRB review.

Subjects

To optimize selection of patients with non-trivial hematochezia, we identified all patients ≥18 years, from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2008, who underwent in-patient colonoscopy for the lone indication “hematochezia” and who had a colonoscopic diagnosis of a bleeding source other than or in addition to hemorrhoids. Moreover, we performed age-stratified analyses whereby we compared older subjects (≥60 years) presenting with non-trivial hematochezia who underwent in-patient colonoscopy for the indication hematochezia and who had a colonoscopic diagnosis of a bleeding source other than or in addition to hemorrhoids with a younger LGIB population (18 to 59 years).

Definitions

We characterized this cohort by demographics, disease co-morbidity per the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) score, gastroenterology practice setting (a priori defined as: “tertiary care” that included academic and VA / military practice sites vs. “community practice” that included community / HMO practices), endoscopic diagnosis, extent of colonoscopy examination, endoscopic hemostasis type, repeat colonoscopy performed, and adverse events (AE).

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons of categorical data were performed using Pearson’s chi-square test of independence. In cases with small cell counts (n < 5), Fisher’s exact test was used. An a priori determined p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS software v. 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Univariate logistic regression was performed for each covariate, modeling likelihood of receiving hemostasis at the time of colonoscopy. All covariates with a univariate p-value < 0.2 were included in the full multivariate model. The parsimonious multivariate model contains only those covariates with a univariate p-value <0.2 that also retained a p-value < 0.2 in the full multivariate model.

Results

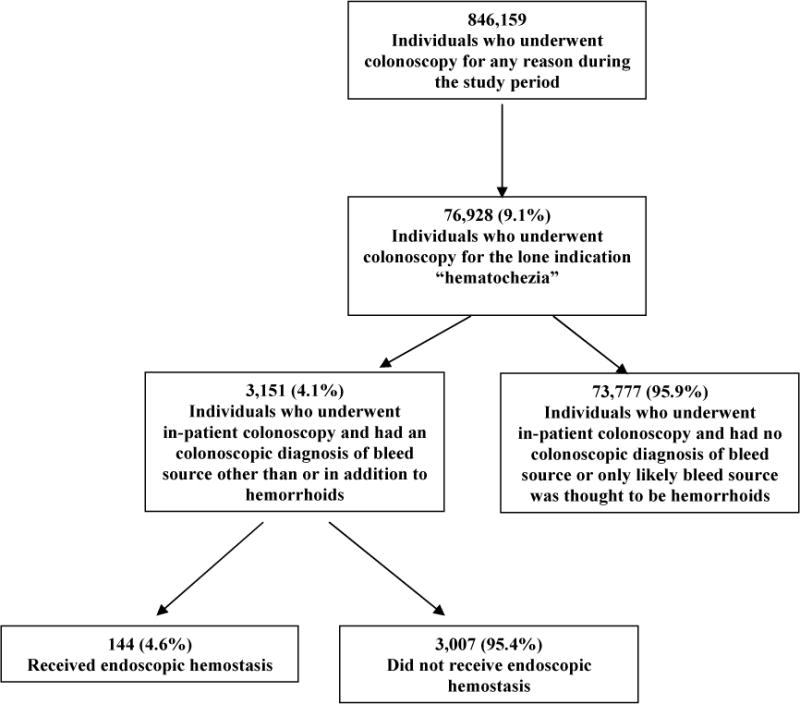

Within the study period, we identified 846,159 who underwent colonoscopy for any reason and 76,928 (9.1%) individuals who underwent colonoscopy for the lone indication “hematochezia”. We further identified 3,151 (4.1%) persons who underwent in-patient colonoscopy for hematochezia and had an endoscopic diagnosis of a bleeding source other than or in addition to hemorrhoids. Endoscopic hemostasis was performed in 144 patients (4.6%), while 3,007 (95.4%) received no hemostasis. See Figure 1. Of the 144 patients who received endoscopic hemostasis, the majority were male (64.6%), White, non-Hispanic (83.3%), older (mean age 70.9 ± 12.3 years), and had a low risk ASA Score (ASA Score = I or II) (53.9%). The majority of patients receiving and not receiving hemostasis underwent colonoscopy in a community hospital setting (67.4% and 69.7% respectively). More specifically, as compared to the cohort of patients who did not receive endoscopic hemostasis, the hemostasis-receiving cohort was significantly more likely to be White (89.6% vs. 80.4% respectively, p=0.006), have more co-morbidities (ASA Score III and IV 46.2% vs. 36.0% respectively, p=0.04), and have their colonoscopy examination reach the cecum (95.8% vs. 87.7%, p=0.003). Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Cohort Demographics Stratified by Endoscopic Therapy

| Hemostasis Performed | No Hemostasis | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=144 | N=3,007 | ||

| Age group (n, %) | 0.3 | ||

| < 50 years | 8 (5.6) | 324 (10.8) | |

| 50 – 59 years | 24 (16.7) | 479 (15.9) | |

| 60 – 69 years | 28 (19.4) | 595 (19.8) | |

| 70 – 79 years | 44 (30.6) | 771 (25.6) | |

| ≥ 80 years | 40 (27.8) | 838 (27.9) | |

| Gender (n, %) | 0.12 | ||

| Female | 51 (35.4) | 1,264 (42.0) | |

| Male | 93 (64.6) | 1,743 (58.0) | |

| Race/Ethnicity (n, %) | 0.02 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 120 (83.3) | 2,134 (71.0) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 9 (6.3) | 476 (15.8) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic | 1 (0.7) | 48 (1.6) | |

| American Indian, non-Hispanic | 3 (2.1) | 45 (1.5) | |

| Multi-Racial, non-Hispanic | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | |

| Hispanic | 11 (7.6) | 298 (9.9) | |

| Unknown/Missing | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.2) | |

| ASA Score (n, %) | 0.04 | ||

| I | 7 (4.9) | 344 (11.4) | |

| II | 63 (43.8) | 1,395 (46.4) | |

| III | 53 (36.8) | 895 (29.8) | |

| IV | 7 (4.9) | 82 (2.7) | |

| V | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 14 (9.7) | 291 (9.7) | |

| ASA Score (n, %) | 0.02 | ||

| I and II | 70 (53.9) | 1,739 (64.0) | |

| III and IV | 60 (46.2) | 977 (36.0) |

Table 2.

Procedure Characteristics and Colonoscopy Findings Stratified by Endoscopic Therapy

| Hemostasis Performed | No Hemostasis | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=144 | N=3,007 | ||

| Site Type (n, %) | 0.71 | ||

| Community/HMO | 97 (67.4) | 2,095 (69.7) | |

| Academic | 19 (13.2) | 407 (13.5) | |

| VA/Military | 28 (19.4) | 505 (16.8) | |

| Depth of Exam (n, %) | |||

| Cecum | 138 (95.8) | 2,636 (87.7) | 0.003 |

| Unplanned Events (n, %) | |||

| Any Unplanned Event | 7 (4.9) | 47 (1.6) | 0.011 |

| Cardiopulmonary Unplanned Event | 4 (2.8) | 44 (1.5) | 0.28 |

| Serious Adverse Event | 3 (2.1) | 3 (0.1) | 0.002 |

| Bleed | 3 (2.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0.0009 |

| Perforation | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | |

| Death | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Colonoscopy Findings (n, %) | |||

| Angiodysplasia | 47 (32.6) | 79 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| Diverticulosis | 98 (68.1) | 2,117 (70.4) | 0.55 |

| Mucosal Abnormality / Colitis | 29 (20.1) | 737 (24.5) | 0.23 |

| Polyp / Multiple Polyps | 58 (40.3) | 1,140 (37.9) | 0.57 |

| Solitary Ulcer | 12 (8.3) | 64 (2.1) | 0.0001 |

| Tumor | 9 (6.3) | 184 (6.1) | 0.95 |

Endoscopic findings reported at colonoscopy included: diverticulosis (68.1% and 70.4%), polyp / multiple polyps (40.3% and 37.9%, mean polyp size 9mm ± 7mm, polyp size range 1mm – 50mm), AVMs (32.6% and 2.6%), mucosal abnormality/colitis (20.1% and 24.5%), solitary ulcer (8.3% and 2.1%), and tumors (6.3% and 6.1%). Some patients had more than one endoscopic diagnosis reported. In the hemostasis-receiving cohort, the endoscopic diagnosis at colonoscopy was significantly more likely to be AVMs (32.6% vs. 2.6%) or solitary ulcer (8.3% vs. 2.1%), p<0.0001 and p=0.0001 respectively. Table 2.

In the 144 patients receiving endoscopic hemostasis, specific endoscopic therapies included: injection 47 (32.6%), bipolar coagulation 44 (30.6%), argon plasma coagulation 42 (29.2%), clips 16 (11.1%), heater probe 6 (4.2%), “other” 4 (2.8%), and band ligation 3 (2.1%). Some patients received more than one one type of endoscopic hemostasis. Table 3. In the overall cohort, there were 85 patients (2.7%) who underwent repeat colonoscopy within 3 days of their index examination, of which 50 (1.6%) underwent repeat colonoscopy within one day. The vast majority, 77/85 (90.6%) underwent repeat colonoscopy for the listed indication “hematochezia”. A total of 6 / 135 (17.4%) patients received hemostasis at the time of repeat colonoscopy. In the patients who at index colonoscopy received hemostasis (n=144), one had a repeat colonoscopy within 1 day and two patients had a repeat colonoscopy within 3 days, all for the indication “hematochezia”. Of the three patients who underwent repeat colonoscopy, 1 received repeat hemostasis using injection therapy.

Table 3.

Endoscopic Hemostasis Type

| Therapy Type | N | % of Therapy Group (N=144) |

|---|---|---|

| Any Therapy | 144 | 100.0% |

| Injection | 47 | 32.6% |

| Bipolar Coagulation | 44 | 30.6% |

| APC | 42 | 29.2% |

| Clips | 16 | 11.1% |

| Heater Probe | 6 | 4.2% |

| Other Treatment | 4 | 2.8% |

| Banding | 3 | 2.1% |

Unplanned events (4.9% vs 1.6%, p=0.011) and serious adverse events (2.1% vs 0.1%, p=0.009) were significantly higher in the hemostasis-receving cohort (p=0.009). There were no perforations or deaths in the hemostasis-receiving cohort, yet one patient had a perforation at colonoscopy in the non-hemostasis cohort. Table 2.

Age-Stratified Analyses

There were n=2,316 patients ≥60 years of age (60–69 years 26.9%, 70–79 years 35.2%, and ≥80 years 37.9%) who underwent in-patient colonoscopy for hematochezia and had a colonoscopic diagnosis of a bleeding source other than or in addition to hemorrhoids. Endoscopic hemostasis was performed in only 112 (4.8%) of those patients, while 2,204 patients (95.2%) did not receive endoscopic hemostasis. In both cohorts, the majority were male (65.2% and 54.5%), White, non-Hispanic (87.5% and 76.2%, p=0.006), and with mean ages 76.2 ± 7.6 years and 76.5 ± 8.9 years, respectively. Most patients underwent colonoscopy in a community hospital setting (66.1% and 73.9%) and had a low risk ASA Score (ASA Score = I or II) (45.6% and 54.3%). Endoscopic findings included: diverticulosis (72.3% and 79%), polyp/multiple polyps (42.9% and 40.6%), angiodysplasia (32.1% and 2.9%), mucosal abnormality/colitis (20.5% and 21.1%), tumor (7.1% and 6.5%), and solitary ulcer (6.3% and 1.6%) in the therapy performed and not performed groups respectively. In both cohorts, colonoscopy reached the cecum most of the time (95.5% and 87.3%, p=0.003), Tables 4 and 5. Endotherapies included: injection 37 (33.0%), argon plasma coagulation 35 (31.3%), bipolar coagulation 32 (28.6%), clips 14 (12.5%), heater probe 4 (3.6%), other 3 (2.7%), and band ligation 1 (0.9%). There were 43 (1.9%) and 70 (3.0%) patients who underwent repeat colonocopy within one or three days respectively, of their index examination. A total of 4 of 113 (3.5%) patients received hemostasis during repeat colonoscopy. Serious adverse events were uncommon, and only included bleeding in n=3 (2.7%) of the hemostasis-receiving group.

Table 4.

Cohort Demographics in Older Adults Stratified by Endoscopic Therapy

| No Hemostasis | Hemostasis Performed | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=2,204 | N=112 | ||

| Age group (n, %) | 0.65 | ||

| 60–69 | 595 (27.0) | 28 (25.0) | |

| 70–79 | 771 (35.0) | 44 (39.3) | |

| ≥80 | 838 (38.0) | 40 (35.7) | |

| Gender (n, %) | 0.03 | ||

| Female | 1,004 (45.6) | 39 (34.8) | |

| Male | 1,200 (54.5) | 73 (65.2) | |

| Race/Ethnicity (n, %) | 0.014 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1,676 (76.0) | 98 (87.5) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 295 (13.4) | 5 (4.5) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic | 27 (1.2) | 1 (0.9) | |

| American Indian, non-Hispanic | 21 (1.0) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Multi-Racial, non-Hispanic | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hispanic | 180 (8.2) | 5 (4.5) | |

| Unknown/Missing | 4 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ASA Score (n, %) | 0.17 | ||

| I | 179 (8.1) | 5 (4.5) | |

| II | 1,019 (46.2) | 46 (41.1) | |

| III | 707 (32.1) | 45 (40.2) | |

| IV | 69 (3.1) | 6 (5.4) | |

| V | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 230 (10.4) | 10 (8.9) | |

| ASA Score (n, %) | 0.03 | ||

| I and II | 1198 (60.7) | 51 (50.0) | |

| III and IV | 776 (39.3) | 51 (50.0) |

Table 5.

Procedure Characteristics by Therapeutic Status in Patients ≥60 Years of Age

| No Hemostasis | Hemostasis Performed | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=2,204 | N=112 | ||

| Site Type (n, %) | 0.14 | ||

| Community/HMO | 1,628 (73.9) | 74 (66.1) | |

| Academic | 246 (11.2) | 14 (12.5) | |

| VA/Military | 330 (15.0) | 24 (21.4) | |

| Depth of Exam (n, %) | |||

| Cecum | 107 (95.5) | 1,925 (87.3) | 0.019 |

| Unplanned Events (n, %) | |||

| Any Unplanned Event | 5 (4.5) | 40 (1.8) | 0.06 |

| Cardiopulmonary Unplanned Event | 2 (1.8) | 37 (1.7) | 0.71 |

| Serious Adverse Event | 3 (2.7) | 3 (0.1) | 0.002 |

| Bleed | 3 (2.7) | 2 (0.1) | 0.001 |

| Perforation | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | ~1.00 |

| Death | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Colonoscopy Findings (n, %) | |||

| Angiodysplasia | 36 (32.1) | 64 (2.9) | 0.0001 |

| Diverticulosis | 81 (72.3) | 1740 (79.0) | 0.10 |

| Mucosal Abnormality / Colitis | 23 (20.5) | 466 (21.1) | 0.88 |

| Polyp / Multiple Polyps | 44 (39.3) | 839 (38.1) | 0.80 |

| Solitary Ulcer | 7 (6.3) | 36 (1.6) | 0.004 |

| Tumor | 8 (7.1) | 144 (6.5) | 0.80 |

This older age cohort stratified by receipt of endoscopic hemostasis, differed significantly with regard to a number of endpoints. Specifically, the hemostasis-receiving cohort had significantly more males (p=0.03), Whites, non-Hispanic (p=0.014), colonoscopies that reached the cecum (95.5% vs. 87.3%, p=0.009), and serious AEs (2.7% vs 0.1%, p=0.002). Endoscopic diagnosis was significantly more often AVMs and solitary ulcer, p<0.0001 and p=0.004, respectively. Tables 4–5

Predictors of Endoscopic Hemostasis

Using logistic regression analysis, we also evaluated for predictors of receiving endoscopic hemostasis (e.g., age, gender, ASA class, site type, cecum reached, unplanned event, endoscopic finding), using receipt of endoscopic hemostasis as the dependent variable. We found the odds of receiving endoscopic hemostasis were 18.6 times higher (95% CI 12.1–28.6 p<0.0001) when angiodysplasia and 5.8 times higher (95% CI 2.9–11.5 p<0.0001) when solitary ulcer was the endoscopic diagnosis at colonoscopy. We also found that the odds of receiving hemostasis were 3.7 times higher when there was an unplanned event and 3.0 times (95% CI 1.1–8.4 p=0.03) higher when the cecum was reached. Table 6.

Table 6.

Multivariate Analysis of Predictors of Receiving Endoscopic Hemostasis

| OR [95% CI] | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Angiodysplasia | 18.6 [12.1–28.6] | <0.0001 |

| Solitary Ulcer | 5.8 [2.9–11.5] | <0.0001 |

| Unplanned Event | 3.7 [1.6–8.9] | 0.0031 |

| Cecum Reached | 3.0 [1.1–8.4] | 0.03 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

Multivariate analysis was adjusted for age, gender, and ASA class

Discussion

In this population-based, study, using the CORI National Endoscopic Database, we describe and compare patients with hematochezia who underwent colonoscopy and received endoscopic hemostasis with those who did not receive endoscopic hemostasis. To optimize selection of patients with non-trivial hematochezia, we limited our analyses to those adult patients who underwent in-patient colonoscopy for the lone indication “hematochezia” and had a colonoscopic diagnosis of a bleeding source other than or in addition to hemorrhoids. In addition, we performed age-stratified analyses comparing older patients (≥60 years) presenting with acute LGIB to younger LGIB patients.

The use of endoscopic hemostasis during colonoscopy for acute LGIB are derived almost exclusively from expert clinical experience at tertiary care hospitals [1]. In contrast to acute upper GI bleeding, there are almost no population-based data that evaluates the use of endoscopic hemostasis in patients presenting with hematochezia. The published reports that do exist are prospective or retrospective cases series that describe the use of a specific hemostasis modality in a specific subgroup of patients delivered almost exclusively by experts. For example, Jensen and colleagues reported on the endoscopic treatment of diverticular hemorrhage [16]. In that prospective case series, all 10 (100%) patients received endoscopic hemostasis for definitive diverticular hemorrhage using dilute epinephrine injection ± bipolar coagulation. No rebleeding was reported in any patient in the subsequent 30 day follow up period. Green et al reported, as part of a randomized trial comparing urgent vs standard colonoscopy in patients presenting with acute lower GI bleeding, that 17/50 (34%) of those undergoing urgent colonoscopy received endoscopic hemostasis for an identified colonic source of bleeding [17]. More recently, in a retrospective case series, Kaltenbach and colleagues reported on the safety and efficacy of endoscopic clipping for severe diverticular bleeding in 64 patients at two separate VA hospitals [18]. As compared to such published reports from tertiary care centers, we found only a minority of patients (4.6%) received endoscopic hemostasis. This is likely due to this present study being a “snap-shot” of population-based data from primarily community practice gastroenterology sites. In this present study, we found that that in the patients receiving endoscopic hemostasis, the majority were White, non-Hispanic men who were older in age, and had a low risk ASA Score. More than two-thirds of patients, both those receiving and not receiving hemostasis, underwent colonoscopy in a community hospital setting.

In this present study, we also found that the hemostasis-receiving cohort was significantly more likely to be White, have more co-morbidities per ASA score, and have their colonoscopy exam reach the cecum. We also found that those patients receiving endoscopic hemostasis had an endoscopic diagnosis at colonoscopy that was significantly more likely to be AVMs or solitary ulcer. Kanwal and colleagues previously reported on the role of endoscopic hemostasis for patients with hematochezia who underwent urgent colonoscopy and found to have a rectal ulcer with major stigmata (e.g., active bleeding, non-bleeding visible vessel, or adherent clot) [19]. Endoscopic hemostasis was performed in 12/23 (52.2%) such patients. Primary hemostasis was achieved in all patients, but 5/12 (41.7%) rebled and four patients died secondary to co-morbid medical conditions [19]. The most common endoscopic hemostasis therapies used in this present study were injection, bipolar coagulation, and argon plasma coagulation. We also found that unplanned events and serious adverse events were significantly higher in the hemostasis-receving cohort.

In the age-stratified analyses, we found similar findings. Endoscopic hemostasis was performed in only 4.8% of patients over age 60 years. The majority of older patients receiving endoscopic hemostasis were White, non-Hispanic males who had a low risk ASA score and underwent colonoscopy in a community hospital setting. As compared to older patients who did not receive endoscopic hemostasis, the hemostasis-receiving cohort had significantly more White, non-Hispanic males, colonoscopies that reached the cecum, and had more serious AEs.

In analyzing potential clinical predictors of receiving endoscopic hemostasis, we found the odds of receiving endoscopic hemostasis were significntly higher when an endoscopic diagnosis of angiodysplasia or solitary ulcer was made at colonoscopy. We also found that the odds of receiving hemostasis were significantly more likely when there was an unplanned event and when the cecum was reached.

There are a number of strengths to this study. We used the CORI National Endoscopic Database as the primary data source. CORI uses standardized and strict quality control measures for all of its data. The endoscopic data in CORI are derived from a variety of GI practice type settings, with highly varied patient demographics, and the majority of CORI sites are community based providing a real world view of endoscopic practice. Moreover, CORI has been used as the primary endoscopic data source for multiple previously published studies [9–15]. This includes CORI data that we evaluated on patients presenting with non-variceal upper GI hemorrhage and more recently on patients presenting with severe hematochezia [8,13,14]. However, this present study has several limitations. The CORI endoscopic report is the sole source of data in this study. Therefore, clinical information (patient-level data) beyond the endoscopic report is limited, including clinical correlation with the severity of the hemtaochezia (e.g., hypotension, anemia, transfusion requirements), medication use, exact timing of colonoscopy, adequacy of colon preparation, or other diagnostic studies (e.g., radiographic, nuclear medicine, angiographic) which may have been performed before or after colonoscopy. In addition, due to limitations of the CORI database, we do not know that the reported endoscopic findings “definitively” confirm the underlying etiology of the hematochezia. The information in the CORI database represents the input of the physician that performs the endoscopy and thus the use of check box notation and free text is variable. Additionally, analysis of follow-up data in CORI is limited. Although in this present study we showed that a small minority of patients underwent repeat colonoscopy within one to three days of their index colonoscopy, colonoscopic examinations that may have been performed for recurrent hematochezia at non-CORI participating sites are not captured in our data and analysis. As a result, our repeat colonocopy data may be an “at least” figure as some patients may have sought care at a non-CORI participating site and thus would not have been captured. In our study, lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage was diagnosed based on the endoscopist’s suspicion to proceed with colonoscopy based on the patient’s presenting symptoms, physical exam, and laboratory data. Our study used repeat colonoscopy within one and three days of index colonoscopy as a surrogate marker for recurrent hematochezia. Repeat colonoscopy may have had nothing to do with recurrent hematochezia and may only indicate some other reason for a “second look” examination (e.g., an incomplete exam, or poor / mediocre prep at index colonoscopy). Thus, given the retrospective nature of this study, we cannot discern the true indication for repeat colonoscopy. Finally, CORI sites are not necessarily a random sample of GI practices in the US and are susceptible to site selection bias. In addition, any observed differences between “academic” sites and “community” sites are observations based upon stratification by CORI site type and are not direct comparisons between sites. Thus, the ability to draw firm conclusions regarding any differences is limited. Despite these limitations, the CORI database remains unique in that it provides us with insight into how “real-life” colonoscopy and endoscopic hemostasis are being practiced in the United States. The large number of patients and colonoscopies permits observation of management trends in clinical situations outside traditional tertiary care centers and therefore, the CORI database is a powerful tool for generating future research studies.

In conclusion, less than five percent of persons presenting with non-trivial hematochezia and undergoing colonoscopy in GI community practice appear to receive endoscopic hemostasis. These findings differ from data published from tertiary care centers. This observed difference may be due to several reasons including more selected patient populations seen at tertiary care centers, presence of gastroenterology fellows in training who are learning endoscopic hemostasis techniques, and a higher likelihood of there being endoscopic hemostasis study protocols at tertiary care centers that would treat patients with hematochezia. These present data provide new information on colonoscopy performed for patients with hematochezia evaluated primarily in community practice. Additional population-based studies in hematochezia are warranted as well as evidence-based guidelines to better guide diagnosis and management of these patients.

Less than 5% of persons presenting with severe hematochezia and undergoing inpatient colonoscopy appear to receive endoscopic hemostasis.

The hemostasis-receiving cohort was significantly more likely to be White, have more co-morbidities, and have the cecum reached. Those receiving hemostasis had an endoscopic diagnosis significantly more likely to be arteriovenous malformations or solitary ulcers.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This project was supported in part with funding from NIDDK UO1 DK57132. In addition, the practice network (Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative) has received support from the following entities to support the infrastructure of this practice-based network: AstraZeneca, Bard International, Pentax USA, ProVation, Endosoft, GIVEN Imaging, and Ethicon (GME, JLW, JH). These commercial entities had no involvement in this present research

Glossary

- LGIB

lower gastrointestinal bleeding

- CORI

clinical outcomes research initiative

- NED

national endoscopic database

- OR

Oregon

- USA

United States of America

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- GI

gastrointestinal

- AVM

arterio-venous malformation

- IRB

institutional review board

- VA

veterans affairs

- HMO

health maintenance organization

- NC

north carolina

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This work was presented in part as an oral presentation in “Solutions for Colonic Problems”, May 22, 2012, Digestive Disease Week 2012 in San Diego, CA.

References

- 1.Strate LL, Naumann CR. The role of colonoscopy and radiological prcedures in the management of acute lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:333–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arroja B, Cremers I, Ramos R, et al. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding management in Portugal: a multicentric prospective 1-year survey. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:317–22. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328344ccb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laine L, Shah A. Randomized trial of urgent vs. elective colonoscopy in patients hospitalized with lower GI bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2636–4. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnert J, Messmann H, Medscape Diagnosis and management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:637–46. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chait MM. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding in the elderly. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:147–54. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i5.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strate LL, Ayanian JZ, Kotler G, et al. Risk factors for mortality in lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1004–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rockey DC. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:165–71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gralnek IM, Ron-Tal Fisher O, Holub JL, et al. The role of colonoscopy in evaluating hematochezia – a population-based study in a large consortium of endoscopy practices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:410–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieberman DA, Holub J, Eisen G, et al. Utilization of colonoscopy in the United States: results from a national consortium. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:875–883. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieberman DA, Holub J, Eisen G, et al. Prevalence of polyps greater than 9 mm in a consortium of diverse clinical practice settings in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:798–805. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harewood GC, Lieberman DA. Colonoscopy practice patterns since introduction of medicare coverage for average-risk screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:72–77. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(03)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieberman D, Fennerty MB, Morris CD, et al. Endoscopic evaluation of patients with dyspepsia: results from the national endoscopic data repository. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1067–1075. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enestvedt BK, Gralnek IM, Mattek N, et al. Endoscopic therapy for peptic ulcer hemorrhage: practice variations in a multi-center U.S. consortium. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2568–76. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1311-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enestvedt BK, Gralnek IM, Mattek N, et al. An evaluation of endoscopic indications and findings related to non-variceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in a large multi-center consortium. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:422–29. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lieberman DA, Holub JL, Moravec MD, et al. Prevalence of colon polyps detected by colonoscopy screening in ssymptomatic Black and White patients. JAMA. 2008;300:1417–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen DM, Machicado G, Jutabha RJ, et al. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:78–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green BT, Rockey DC, Portwood G, et al. Urgent colonoscopy for evaluation and management of acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2395–2402. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaltenbach T, Watson R, Shah J, et al. Colonoscopy with clipping is useful in the diagnosis and treatment of diverticular bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:131–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanwal F, Dulai G, Jensen DM, et al. Major stigmata of recent hemorrhage on rectal ulcers in patients with severe hematochezia: endoscopic diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:462–8. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]