Abstract

Background & Aims

Gene expression profiling provides an opportunity for definitive diagnosis but has not yet been well applied to inflammatory diseases. Herein, we describe an approach for diagnosis of an emerging form of esophagitis, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), currently diagnosed by histology and clinical symptoms.

Methods

We developed an EoE diagnostic panel (EDP), comprising a 96-gene quantitative PCR array and an associated dual-algorithm that uses cluster analysis and dimensionality reduction, using a cohort of randomly selected esophageal biopsy samples from pediatric patients with EoE (n = 15) or without EoE (non-EoE controls, n = 14), subsequently vetted using a separate cohort of 194 pediatric and adult patient samples derived from both fresh or formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue: active EoE (n = 91), control (non-EoE and EoE remission, n = 57), histologically ambiguous (n = 34), and reflux (n = 12) samples.

Results

The EDP identified adult and pediatric patients with EoE with ~96% sensitivity and ~98% specificity, and distinguished patients with EoE in remission from controls, as well as identified patients exposed to swallowed glucorticoids. The EDP could be used with FFPE tissue RNA and distinguished patients with EoE from those with reflux esophagitis, identified by pH-impedance testing. Preliminary evidence showed that the EDP could identify patients likely to have disease relapse following treatment.

Conclusions

We developed a molecular diagnostic test (referred as the EDP) that identifies patients with esophagitis in a fast, objective, and mechanistic manner, offering an opportunity to improve diagnosis and treatment, and a platform approach for other inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: EoE, GERD, NERD, diagnostic panel, signature, eosinophil, EoE transcriptome, fluidic card, genomics, transcriptome, esophagus

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a recently identified chronic, immune-mediated, clinico-pathological, upper gastrointestinal (GI) disorder. It is characterized by esophageal dysfunction (e.g. dysphagia) and eosinophilia of ≥15 eosinophils/high-power field (HPF) in patients for whom acid-induced esophageal injury has been excluded 1. The incidence of EoE has continued to increase since its initial characterization two decades ago 2, and EoE now accounts for ~10–30% of chronic esophagitis refractory to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy 1 and 7% of patients who undergo upper GI endoscopy 3. The treatment of EoE is distinct from other forms of esophagitis such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) as effective management depends upon elimination of the triggering food or the usage of anti-inflammatory medications (e.g. glucocorticoids). Until now, the only widely accepted means of diagnosing EoE was based on this histological analysis of esophageal biopsies together with clinical symptom evaluation 4, and it has been suggested that at least 5 biopsies, preferably from both the distal and proximal esophagus, are required to obtain sufficient sensitivity because of the patchiness of disease pathology 5–7. Unfortunately, esophageal eosinophilia is not specific to EoE, as it also occurs in other disease processes including GERD, infections and auto-immune diseases, rendering specificity of histology-based diagnosis problematic 8.

One of the critical findings in understanding EoE pathogenesis was the discovery of the whole-genome mRNA esophageal expression profile (“EoE transcriptome”) 9. The “EoE transcriptome” consists of ~500 EoE genes and has uncovered key pathogenic steps such as the involvement of eotaxin-3 in eosinophil accumulation and activation; the importance of periostin in facilitating eosinophil recruitment and tissue remodeling 10; the critical role of mast cells 11, T cells 12 and the local cytokine milieu 13 in disease pathogenesis; and the importance of impaired local barrier function 14. Ideally, microarray expression can be used to provide diagnosis of EoE 9. However, the long turn-around time, the technical complexity of the mRNA microarray and the associated high financial cost hinder practical clinical application for diagnostic purpose.

In order to utilize the diagnostic strength from the microarray and reduce technical barriers, we developed a molecular EoE Diagnostic Panel (EDP) built on a Taqman®-qPCR-based low-density array system. Herein, we report three major steps in the development and application of EDP. First, we successfully demonstrate that a selected representative EoE gene set (a 94-gene panel) is sufficient to provide EoE diagnosis with high sensitivity and specificity (92–100%, 96–100%, respectively), based on dual computational algorithms in both pediatric and adult EoE. Second, we demonstrate that EoE remission patients can be readily distinguished from normal (NL) patients, which cannot be achieved by conventional methods. Third, we demonstrate the utility of the EDP with FFPE-derived tissue RNA and in distinguishing EoE from GERD, using pH-impedance testing to confirm the presence of acid-induced disease. Taken together, the EDP has promising future applications in the classification of esophagitis and in advancing personalized medicine.

Materials and Methods

Patient sample selection

For algorithm developing cohorts, normal (NL) patients were defined by the distal esophagus (where tissue RNA was obtained) having eosinophil/HPF ≤1 and by not being treated with swallowed or systemic steroids without EoE history. Patients with EoE were selected for having eosinophil/HPF ≥15 in the distal esophagus, typically when on PPI therapy, and by not being treated with swallowed or systemic steroids. Patients with EoE remission were selected based on having partial (≤2 eosinophil/HPF) or complete (≤1 eosinophil/HPF) histological remission (0.6 ± 0.7 eosinophil/HPF, mean ± SD) after topical fluticasone propionate or budesonide treatment. The selection criterion was based on the peak eosinophil count in the distal esophageal biopsies, which is the only tissue type assayed in this report. All EoE patients tested herein were clinically symptomatic pediatric patients less than 21 years old, with the exception of the adult transcriptome assay, which recruited 12 adults > 22 years old. In replication study and the overall study, control samples were defined as eosinophil/HPF ≤ 2. For the collective FFPE diagnostic merit study and the impedance guided study, NL was defined as 0 eosinophil/HPF with no history of EoE), while EoE was defined as ≥ 15 eosinophil/HPF on PPI therapy. For detailed clinical information, see Table S3.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription

Biopsy mRNA/miRNA extraction was carried out routinely by miRNeasy RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, 217004); samples were archived in the −80°C EGID research sample library at CCHMC and registered in an electronic EGID database. An aliquot of RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA by the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad 170-8891). Briefly, 500 ng RNA was mixed with the reaction mixture containing reverse-transcriptase and dNTPs in a total volume of 20 μl; incubated at 25°C for 5 min, 42°C for 30 min, 85°C for 5 min; and then kept at −20°C for storage.

Taqman qPCR amplification with 384-well fluidic cards

An aliquot of cDNA equivalent to 125–500 ng starting RNA was adjusted to 100 μl with H2O and mixed with 100μl TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (4440040, Applied Biosystems) and loaded on fluidic cards. The standard amplification protocol consists of a ramp of 50 °C for 2 min and a hot start of 94.5°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 30 sec at 97°C and 1 min at 59.7°C.

Esophageal pH impedance-guided EDP

We systematically searched the hospital’s (CCHMC) pH-Multichannel Intraluminal Impedance (pH-MII) results for patients who had the pH-MII performed for upper GI symptoms and also had an esophageal biopsy report available concurrently (gap between the two procedures was 2 ± 2 days, mean ± SD, with two exceptions of 65 and 143 days). These 38 patients were divided into four different study cohorts based on their histological report and concurrent esophageal impedance, namely NL (normal pathology, normal impedance), non-erosive reflux disease (NERD, normal pathology, abnormal impedance), GERD (abnormal pathology [2–6 eosinophils/HPF inflammtory infiltration, and/or with neutrophilia, without EoE history], abnormal impedance) and EoE (abnormal pathology [≥15 eosinophils/HPF], normal impedance). We defined an abnormal pH-MII result as having > 80 reflux episodes in 24 hours, which is further defined as a retrograde decrease in impedance baseline that exceeded 50% of the distance between the baseline and the impedance nadir in at least the 2 distal channels. Similar criteria have recently been recognized 15.

Results

Two independent algorithms, cluster analysis and EoE score, successfully differentiate EoE from NL patients

The Taqman® amplification reagents for a panel of 94 representative EoE genes and 2 housekeeping genes were pre-embedded onto a 384-well fluidic card (Tables 1, S1 and S2). Figure 1 offers a schematic summary of the steps involved. For algorithm development, a random set of samples from pediatric patients including NL (n = 14) and EoE (n = 15) samples without exposure to topical or systemic glucocorticoid treatment were selected for initial EDP analysis (for clinical information see Table S3). We identified 77 significantly dysregulated genes out of the 94 genes after false discover rate (FDR) correction 16 (FDR-corrected p < 0.05 by two-tailed T-test, fold change > 2.0). As shown in Figure 2A, we initially examined NL (blue branches) and EoE (red branches) samples with established histological diagnosis and then setup a 2-dimensional dendrogram, clustering on both entities (genes) and conditions (EoE status), based on a Pearson-centered similarity algorithm. The clustering on the Y-axis demonstrated that the up-regulated and down-regulated EoE genes were well represented by the EDP platform. Indeed, judging from the first branch of the dendrogram on the X-axis (condition), the EoE pattern can be readily recognized with a long distance metrics separation on top of the dendrogram. All of the NL samples clustered together while all of the EoE samples grouped together (Fig. 2A). Multi-Dimensional Scaling (MDS) analysis of the 77 differentially expressed EoE genes established a 3-D plot based on Euclid distance between samples (Fig. 2B), which demonstrateda clear separation of EoE and NL samples.

Table 1.

Major EDP gene categories with 5 representative EoE genes

| Cell adhesion | Epithelial related | Inflammation process | Remodeling | Eosinophil/Mast cell | Chemokine/Cytokine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDH26 | FLG | TNFAIP6 | POSTN | CLC | CCL26 |

| DSG1 | UPK1A | ALOX15 | KRT23 | CCR3 | CXCL1 |

| CLDN10 | SPINK7 | ARG1 | COL8A2 | TPSB2/AB1 | IL4 |

| CTNNAL1 | CRISP3 | MMP12 | CTSC | CPA3 | IL5 |

| CHL1 | MUC4 | IGJ | ACTG2 | CMA1 | IL13 |

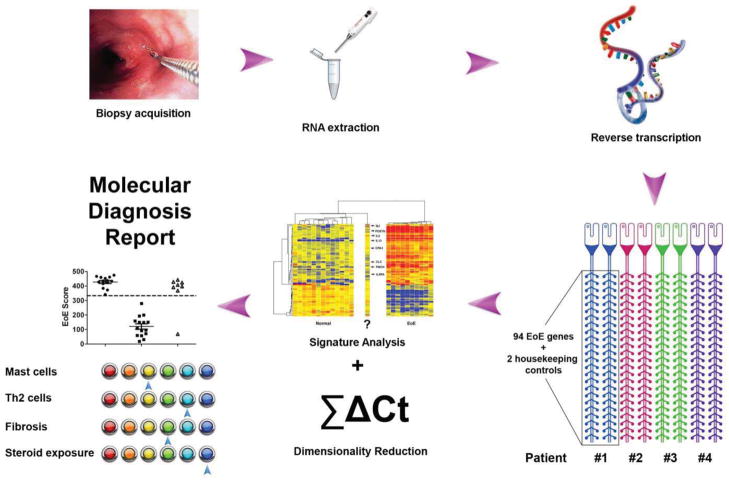

Figure 1. Graphic illustration of EDP standard operating procedures.

The eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) diagnostic panel (EDP) described in this report consists of three major steps, namely RNA extraction, EDP panel qPCR, and data analysis. RNA is extracted from a fresh patient esophageal biopsy or FFPE tissue sections. An aliquot of the RNA sample is subjected to reverse transcription reaction, and the resulting cDNA is loaded onto the 384-well fluidic card (4 patients) for qPCR amplification. The qPCR data are subjected to dual algorithms, namely signature analysis (heat map clustering) and dimensionality reduction (EoE score) to establish molecular EoE diagnosis, which forms the basis for the final diagnostic report with multiple disease pathogenesis component assessment. Th2: type 2 helper T cells; ΣΔCT, sum of normalized CT.

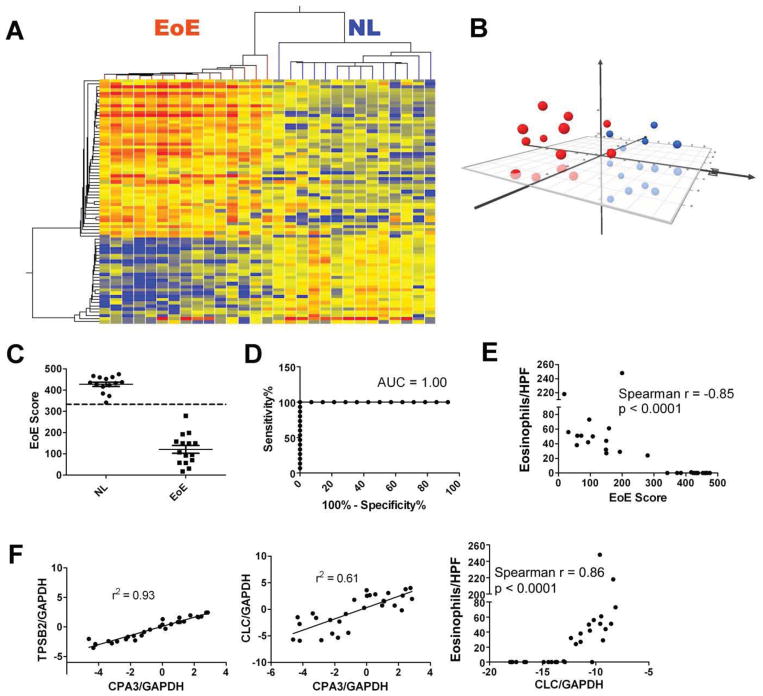

Figure 2. Dual EDP algorithms for molecular diagnosis of EoE.

A, For the 94 EoE genes embedded, a statistical screening was performed between the 14 normal (NL) patients (blue branch) and 15 patients with EoE (red branch), resulting in 77 genes with FDR-corrected p < 0.05 and fold change > 2.0. Based on these 77 core genes, a heat map (red = upregulated) was created, with the hierarchical tree (dendrogram) established on both gene entities and sample conditions. On the x-axis, the first branch of the top tree is utilized to predict EoE vs. NL. B, The 77-gene/dimension expression data on 14 NL controls (blue) and 15 patients with EoE (red) were reduced to 3-D presentation by multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) analysis for visual presentation of the expression distance between samples. C, An EoE score was developed based on dimensionality reduction to distinguish EoE vs. NL and quantify EoE disease severity. A diagnosis cut-off at EoE score = 333 (dashed line) was derived from later, larger-scale studies by Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis. D, ROC curve based on panel C and the EoE score = 333 cut-off, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 1.0. E, A linear correlation between eosinophils/HPF and EoE score, with Spearman r and p values shown. F, To demonstrate gene amplification accuracy, representative linear regressions regarding mast cell gene intra-correlation [CPA3 vs. Tryptase (TPSB2)], mast cell gene/eosinophil gene inter-correlation (CPA3 vs. CLC), and eosinophil gene/eosinophilia correlation (CLC vs. eosinophils/HPF) are shown in the left, middle, and right panels, respectively. All scatter plots were graphed as mean ± SEM.

We also developed a parallel dimensionality reduction algorithm to calculate an “EoE score” (see Methods), with the goal of developing a quantitative diagnostic cut-off. As shown in Figure 2C, the EoE score of the two cohorts was well separated with 100% disease prediction. Notably, the EoE score cut-off (333) was determined through a larger scale study consisting 132 patients (discussed later). With the EoE score algorithm, ROC analysis demonstrated an excellent diagnostic merit with area under curve (AUC) being 1.00 (Fig. 2D). There was a significant correlation between the EoE score and esophageal eosinophil counts (Fig. 2E, p < 0.0001), a surrogate marker of disease severity. Two mast cell markers, carboxypeptidase A3 (CPA3) and tryptase (TPSB2), correlated well with each other (Fig. 2F left panel) indicating intra-panel reproducibility. Also, the gene for eosinophil lysophospholipase (CLC), the only highly expressed eosinophil granule protein gene, positively correlated with mast cell gene levels (Fig. 2F middle panel) and eosinophil counts (Fig. 2F right panel), corroborating prior findings 11.

In a replication study, we also performed EDP analysis on a biologically independent cohort of control (n = 14) and EoE (n = 18) patients (for clinical information see Table S3). The cluster analysis dendrogram predicted control (blue branch) vs. EoE (red branch) with high accuracy (Fig. S1A), while the EoE score algorithm revealed a similar predictive power with little overlap between control and EoE (Fig. S1B, with 333 cut-off). The EoE score cut-off again resulted in an almost rectangular-shaped ROC curve with an AUC of 0.99 (Fig. S1C). Similarly, the EoE score strongly correlated with disease severity (Fig. S1D) as measured by eosinophils/HPF (Fig. S1E). To evaluate the inter-panel reproducibility, we selected two fresh RNA samples with intermediate transcriptome changes (up- and down-regulated genes), re-performed the reverse transcription and processed their cDNA 6 months later with different EDP fluidic cards. In order to confirm the highly reproducible gene expression signature for each gene at its raw CT level, we performed a Bland-Altman analysis on the raw CT value of each of the 96 genes (x-axis) and the CT value difference between the prior run and the average of both runs (y-axis) (Fig. S2A; test A, early run; test B later run; blue, sample I; red, sample II). The flat line distribution along the x-axis (difference = 0) for both samples indicates that the raw CT value between different EDP amplifications are highly stable for the 96 embedded genes. To further test the correlation between the two independent EDP analyses, we performed the linear correlation of the 96 genes on the dual runs with spearman r > 0.98 (95% CI, Fig. S2B), indicating a highly correlated signature analysis for each gene.

EDP indicates a comparable EoE transcriptome between adult and pediatric samples

We aimed to determine whether the EDP would be sufficient across age groups. Adult and pediatric patients with EoE (matched for eosinophil levels) were subjected to the EDP analysis (Fig. S3A and S3B). Notably, the 77 core gene expression signatures were largely comparable between pediatric and adult patients with EoE by both clustering and EoE score analyses (Fig. S3C and S3E). MDS analysis indicated two distinct groups when pediatric NL (blue dots) and EoE (red dots) samples were analyzed, indicating a large Euclid distance (Fig. S3D left panel); in contrast, pediatric EoE (red) and adult EoE (blue) samples exhibited a mixed pattern due to a similar signature (Fig. S3D right panel).

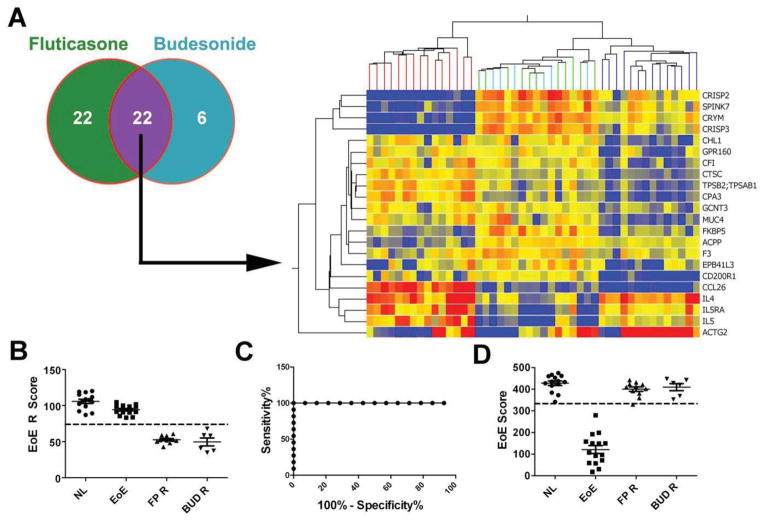

The EDP identifies EoE remission status

The dysregulated expression of a subset of the EoE transcriptome is resistant to steroid therapy even when steroid therapy induces remission, i.e. the absence of tissue pathology including eosinophilia 17. In addition, there is a unique set of genes that are upregulated in response to glucocorticoid exposure 18. Therefore, we included a selection of “EoE remission genes”, as well as several steroid-induced markers, in the EDP design, aiming to distinguish EoE remission and NL and to assess glucocorticoid exposure (for genes related to these purposes, see Table S2). EDP analysis of esophageal biopsies from patients with EoE responding well to swallowed topical fluticasone propionate (Flovent, green) therapy or budesonide (Pulmicort, light blue) identified 44 and 28 dysregulated genes, respectively, with an overlap of 22 genes between the two steroids (Fig. 3A). Within this 22-gene set, we derived a scoring algorithm, EoE remission (EoE R) score, to quantitatively differentiate between NL and EoE remission. Judged by an ROC-derived cut-off of EoE R score = 74, NL and the two EoE remission cohorts were well discriminated (Fig. 3B). The rectangular-shaped ROC curve demonstrated high diagnostic merit (Fig. 3C). Notably, the 77-gene EoE definitive diagnosis cluster on the same panel could not distinguish the remission cohorts from the NL cohort, which is conceivable as these are inactive samples (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. EDP is able to discriminate patients with EoE remission from normal patients.

A, EoE transcriptome profiles from 17 patients with EoE remission [treated with swallowed fluticasone propionate (FP) n = 11 or budesonide (BUD) n = 6] were acquired by EDP. Statistical analysis between the normal (NL) cohort and the two EoE remission cohorts was performed (FDR corrected p < 0.05, fold change >2.0), which resulted in 22 significant genes present in both FP- and BUD-regulated gene sets. On the basis of this 22 remission genes, a double-clustered heat map was generated to evaluate the gene expression pattern of EoE remission (FP, green; BUD, light blue) compared to NL (blue) and EoE (red). B, The remission score (EoE R score) for each patient was calculated by 1-D reduction with the same formula for EoE score to differentiate the patients with EoE remission (FP R and BUD R, R = remission) from the NL ones quantitatively. C, A diagnostic cut-off line of EoE R score = 74 was derived from ROC analysis, which has an AUC of 1.00. D, On the basis of the 77 EoE diagnostic genes, EoE scores were also calculated to assess the EoE status of these remission patients. The EoE score = 333 cut-off line is indicated on the graph. All scatter plots were graphed as mean ± SEM.

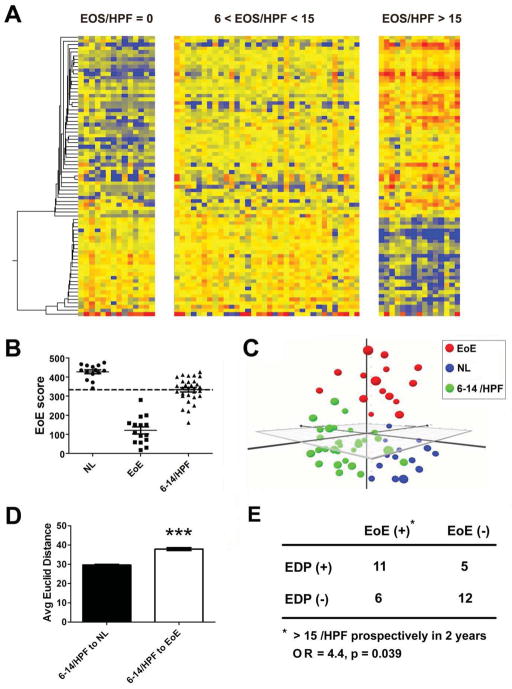

EDP analysis of histologically ambiguous patients identifies a significant subset of EDP-positive patients associated with worse prognosis

In clinical practice, when esophageal eosinophil numbers are less than the diagnostic threshold (e.g. in the range of 6–14 eosinophils/HPF), a diagnostic dilemma is posed. In order to clarify potential EoE cases within this “sub-diagnosis zone” 13, we utilized the EDP and the associated algorithms to assess the signature of this histologically ambiguous population in a cohort of 34 pediatric patients with eosinophil counts in the sub-diagnosis zone (6–14 eosinophils/HPF). Juxtaposition of the expression signatures of the histologically ambiguous patients with NL and EoE reference cohorts (Fig. 4A) demonstrated that the ambiguous cohort had a unique molecular signature with EoE up-regulated genes modestly increased but EoE down-regulated genes largely unchanged. When analyzed by the EoE score algorithm, indeed 47% of these patients (16 out of 34) had a positive EDP score (Fig. 4B). After dimensionality reduction, we further positioned this ambiguous cohort (green, n = 34) onto a 3-D expression plot by MDS (Fig. 4C), demonstrating that the signature of these patients was distinguished from NL (blue) and EoE (red) reference cohorts with their Euclid distance closer to NL (Fig. 4D). In order to study whether this initial signature change could be predictive for long-term prognosis of EoE, we examined the clinical outcomes of these 34 patients (with 6–14 eosinophils/HPF) by tracking their medical records and found that 69% of the EDP positive patients and 33% of the EDP negative patients developed active EoE (≥ 15 eosinophils/HPF) within 2 years (1.2 ± 0.5 years, Mean ± SD, range 0.4–2 years, n = 17). In Figure 4E by χ2 test, there was a substantial risk for developing active EoE after a positive EDP (O.R. 4.4; P = 0.039).

Figure 4. EoE transcriptome pattern in the patient population with ambiguous eosinophil levels, 6–14 eosinophils/HPF.

A, To acquire the esophageal signatures of 34 patients with noticeable eosinophilia that did not exceed the diagnostic cut-off [6 < eosinophils (EOS)/high-power field (HPF) < 15], EDP-based expression signatures were juxtaposed with the reference normal (NL, 0 eosinophils/HPF) and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE, >15 eosinophils/HPF) cohorts. B, The EoE score algorithm was utilized to assess EoE signature within the population with ambiguous eosinophil levels of 6–14 eosinophils/HPF (6–14/HPF). The EoE score scatter plot indicates that ~ 47% (16/34) patients in this sub-diagnosis zone were EDP positive as determined by the 333 EoE diagnostic cut-off (dashed line). C, Multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) analysis was carried out to visualize the expression difference between the 6–14-eosinophil cohort (green) and NL (blue) and EoE (red) reference cohorts. D, The average (Avg) Euclid distances from the 6–14-eosinophil cohort to the NL and EoE cohorts, respectively, were graphed as mean ± 95% CI, revealing their collective Euclid distance to NL and EoE reference cohorts, respectively. (*** p < 0.001) E, All 34 patients with ambiguous eosinophil levels (6–14 eosinophils/HPF) were clinically followed for 2 years based on their medical record. The association between EDP results and subsequent active EoE (>15 eosinophils/HPF) (in 1.2 ± 0.5 years, Mean ± SD) was graphed in the χ2 table. The odds ratio (OR) of 4.4 was calculated based on the relative risk factor for EoE development, EDP-positive (EoE score < 333) vs. EDP-negative result, with a significant p value = 0.039 by χ2 test.

FFPE compatibility and a pH impedance-based study for EoE vs. GERD differentiation by EDP analysis

We next explored whether the EDP was able to analyze FFPE sections from EoE and NL samples defined by histological criteria in clinically symptomatic EoE patients. Cluster analysis of NL (n=21) and EoE (n=24) FFPE samples demonstrated a pronounced separation between the two groups (Fig. S4A), resulting in a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 100%. Likewise, the EoE score algorithm separated the same NL and EoE cohorts in the FFPE format with high merit (sensitivity 92%, specificity 100%). With an AUC of 0.96 from ROC analysis and an optimized cut-off of 355 (Fig. S4B), the performance of the EDP of FFPE samples proved to be comparable to fresh samples. In addition, we wanted to assess the reproducibility between two different section-cuts from the same FFPE block, which is a function of both histological and technological variations. The two FFPE RNA extractions and EDP amplifications were performed at least one month apart. The raw CT values were 2-D plotted (cut1 vs. cut2) to reveal the correlation of the adjacent section inputs (8 × 10 μm cut twice), which indicated a high reproducibility between different tissue inputs on the same archived tissue (Fig. S4C). Finally, we evaluated the correlation between a FFPE biopsy and a fresh biopsy taken simultaneously from the same patient; notably, a high correlation for individual gene expression was observed (Fig. S4D). Across larger cohorts, comparing the algorithm developing cohort (fresh, n=29) and the above FFPE cohorts (n=45), the dysregulation vectors (fold change EoE over NL; red indicating up regulated genes; blue for down) robustly correlate between fresh and FFPE samples (r2=0.87, Fig. S4E). Figure S4F left panel illustrates a representative 230–280 nm spectrometry result for RNA isolated from 80 μm FFPE sections with high RNA purity and μg level abundance. RNA integrity analysis by the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer revealed substantial FFPE RNA degradation as a function of time (Fig. S4F right panel); however, the EDP performance was unaffected, as the FFPE samples had a conserved signature pattern compared with fresh RNA even though the RNA was 0–3 years old (Fig. S4A–B). Collectively, these data demonstrated that the dual diagnostic algorithms derived from fresh samples readily applied to clinically archived FFPE samples and results in uncompromised diagnostic merit.

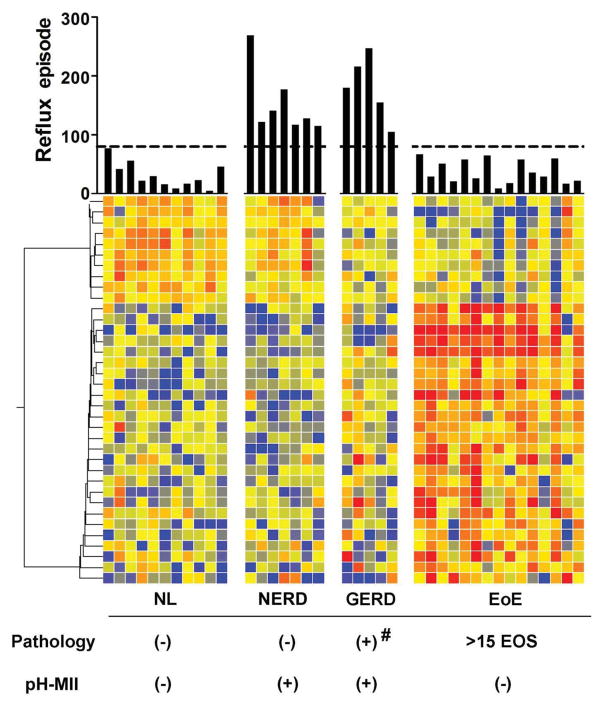

In order to definitively prove the capacity of the EDP to differentiate EoE from GERD and to further validate the FFPE sample compatibility, we examined a cohort of 38 patients with upper GI symptoms who concurrently underwent both EGD and esophageal pH – Multichannel Intraluminal Impedance (pH-MII) analysis. The expression heat map was juxtaposed based on core EoE genes and patient grouping conditions with their reflux episodes within 24 hours displayed by overhead bars (Fig. 5). For pH-MII reading, we used > 80 episodes cut-off to define reflux condition (see Methods for pH-MII definition and grouping criteria herein). The Non-Erosive Reflux Disease (NERD) group was highly comparable to NL controls; likewise, the expression pattern of the pathological GERD cohort was molecularly similar to that of NL controls.

Figure 5. A pH impedance-guided EDP analysis aiming to discriminate NERD/GERD from EoE.

The EDP was performed on a selected cohort of 38 patients who had pH-Multichannel Intraluminal Impedance (pH-MII) results from the time of endoscope procedure; they were categorized into four different cohorts based on pathology findings and pH-MII test. Expression heat map was generated based on 36 significant genes after a statistical screening between NL patients and patients with EoE (FDR corrected p < 0.05, fold change >2.0). Four study cohorts, namely NL, non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), GERD and EoE were juxtaposed for signature comparison. The overhead “Reflux episode” bars indicate the number of esophageal reflux episodes within 24 hours by pH-MII with a cut-off of 80 displayed. # = 2–6 eosinophils/HPF and/or with neutrophilia; EOS, eosinophils. EDP was performed on FFPE-derived RNA in this retrospective study.

Overall EDP analysis on a larger scale

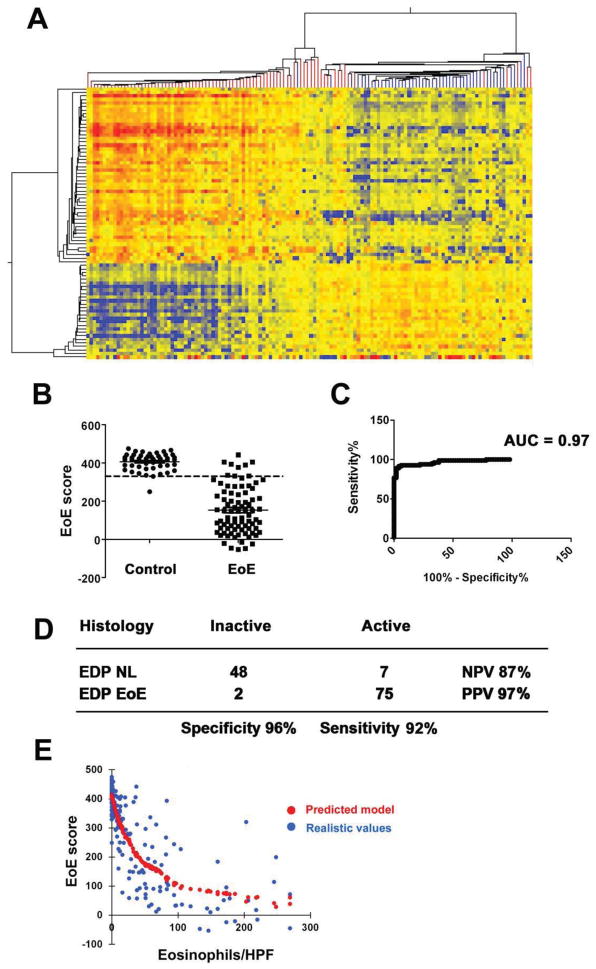

We next aimed to evaluate the diagnostic merits of the EDP by examining the transcription signatures of 166 fresh RNA samples. Among the 166 patients, 132 had eosinophil counts in the ranges in which diagnosis was considered unambiguous (e.g. ≤2 or ≥15 eosinophils/HPF), forming the control and EoE pool, respectively (for clinical information see Table S3). The clustering analysis indicated the distinct cohorts of EoE transcriptome and NL-like transcriptome (Fig. 6A). Under the first branch, the uniformity of tree color reflects diagnostic merit. Using the EoE score algorithm (Fig. 6B) and ROC cut-off optimization (Fig. 6C), we demonstrated that the EDP had an excellent coverage between sensitivity (92%) and specificity (96%) and a high Area Under Curve (AUC) of 0.97 (Fig. 6C and 6D). In order to assess whether EoE score could reflect disease severity as measured by histology (e.g. eosinophils/HPF) for these 166 cases, we performed nonparametric regression analysis with the predicted model shown in red dots and the true values shown in blue dots (Fig. 6E). The r2 of 0.68 is indicative of a strong correlation between the 1-D EoE score and tissue eosinophilia, which is the currently accepted gold standard for measurement of disease activity.

Figure 6. Overall assessment of EDP merit.

To assess the dual algorithms of the EDP on a larger scale, we collected EDP signatures for a total of 166 patients, in which there are 82 patients with EoE [≥ 15 eosinophils (EOS)/high-power field (HPF)] and 50 control patients (≤ 2 EOS) by histology. A, With the clustering algorithm by 1st branch, a double-clustered heat map (red branch, EoE; blue branch, control) indicates that EDP clustering algorithm is highly competent at positive prediction, with only one control misdiagnosed as EoE (single blue branch in the EoE cluster on the left). B, EoE scores from histology-defined 50 control patients and 82 patients with EoE were plotted over the 333 diagnostic cut-off (determined herein and used throughout this report), resulting in an optimized balance between sensitivity and specificity. The scatter plots were graphed as mean ± SEM. C, The ROC curve of EDP diagnosis in B with 132 patients in reference to histological method. AUC: area under the curve. D, On the basis of the EoE score analysis in B and C with the histology as gold standard, the EDP’s diagnostic merit was summarized in specificity vs. sensitivity and PPV vs. NPV, reflecting the diagnosing power in clinical practice. E, The correlation between tissue eosinophilia (eosinophils/HPF) and EoE score was analyzed by LOWESS (Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing) nonparametric regression and plotted with the predicted trend (red) and realistic values (blue), indicating a negative relationship with r2 = 0.68 and reflecting disease severity.

Discussion

EoE is an emerging and enigmatic disease, whose diagnostic standards still remain debatable. In this report, we demonstrated a readily performed molecular platform providing differential diagnosis of EoE vs. NL and inactive EoE, EoE vs. NERD/GERD and EoE remission vs. NL by dual computational algorithms. The EDP panel was shown to be FFPE sample compatible with comparable merit to analysis of fresh tissue and applicable to pediatric and adult EoE. The EDP also demonstrated the predicative capacity for patients with subclinical histology suggesting that these patients should be tightly monitored as an EoE high-risk population and that the EDP may be potentially used as a personal medicine prediction device. The EDP has the potential to overcome the limitations of histological analysis, as it provides potentially deeper insight into tissue processes that are not all visible microscopically or that may be microscopically patchy, highlighting the transformative value of using molecular parameters compared with histology for the diagnosis of inflammatory diseases. Furthermore, the EDP has the capacity to reveal EoE pathogenesis that could vary from patient to patient, forming the basis for practicing personal medicine. It is important to note that the EDP has a high performance using only one distal esophageal biopsy even though consensus recommendations include procurement of five biopsies 1.

The EDP can readily differentiate topical-steroid-induced EoE remission samples from NL samples by both algorithms — a capacity histology does not have, and subjective steroid compliance may be objectively predicted with steroid-responding biomarkers. Besides the steroid intervention assessment, a future EDP study should also be performed in the context of diet retreatment. It would be interesting to prospectively evaluate the effects of multiple forms of diet therapy, such as elimination vs. elementary, in reference to steroid effects. Importantly, it is proposed that, with a paired-sample study before and after EoE treatments, the EDP (in its current form or with modified composition) will predict which treatment is more effective (e.g. reversing the EDP signature). This approach will be critically important for selection of the most effective intervention for EoE patientswhich is currently not fully agreed upon.

In clinical practice, physicians often face a diagnostic dilemma when patients with esophagitis have clinical symptoms comparable to EoE yet have endoscopic findings with less than 15 eosinophils/HPF 19. Thus, the cut-off value of 15 eosinophils/HPF has been recently questioned, even in a recent Consensus Report 1. Even within one biopsy, the eosinophil number varies from site to site. Indeed, the EoE score algorithm indicated that 47% of the histologically ambiguous patients are molecularly equivalent to active EoE patients. Fifty percent of these histologically ambiguous patients later developed histologically active EoE within a 2-year period, indicating that these patients are at high risk for active EoE. A positive EDP coupled with sub-clinical non-remission histology (6–14 eosinophils/HPF) increased the likelihood of fully active EoE in the next 2 years, as indicated by the 4.4-fold odds ratio between EDP-positive and EDP-negative histologically ambiguous patients, demonstrating a potential predictive medicine capacity. Although this data is limited by the non-prospective design, it is consistent with the recent finding that long-term consequences of esophageal eosinophilia emerge at eosinophil levels >5 eosinphils/HPF 20 and with another study showing that 36% of the “low-grade esophageal eosinophilia” cases (1–14 eosinophils/HPF) are truly EoE as proved by subsequent repetitive endoscopy 19.

An EDP analysis of 177 patient samples (132 fresh and 45 FFPE) achieved the historically high ~98% specificity and ~96% sensitivity using the EoE score (ΣΔCT) algorithm. Notably, it is likely that the diagnostic merit of EDP is underestimated, because the caveat for this study is using the histological method as the “gold standard”. As mentioned previously, the 15 eosinophils cut-off itself is debatable due to the heterogeneity of eosinophilia, the variability of counting and shared eosinophilia with non-EoE diseases. On the other hand, although the EDP demonstrated unprecedented performance using samples from our institution and was able to perform well with fresh and FFPE samples from other sites in multi-centered studies (data not shown), an external validation will be helpful to strengthen the EDP application. With high diagnostic merit, a value for personalized medicine and ability to distinguish EoE remission tissue from healthy tissue, the EDP represents the next-generation for EoE diagnosis. Although histological diagnosisby eosinophil count and an empirical eosinophilia cut -off will still prove to be useful under certain circumstances, the EDP offers an accurate, rapid, informative and low-cost diagnosis based on the EoE transcriptome as a biomarker for evaluating therapeutic interventions. Our results provide proof-of-principle for the application of tissue-based molecular diagnosis of inflammatory diseases, especially for esophagitis and a growing number of other eosinophil-associated inflammatory diseases such as asthma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported by NIH grants R37 A1045898, R01 AI083450, P30 DK078392, 3 R01 DK076893 and U19 AI070235; the University of Cincinnati Institutional CTSA; the CURED (Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Disease) Foundation; the Food Allergy Initiative; and the Buckeye Foundation.

The authors thank Drs. Carine Blanchard and Bruce Aronow for helpful early discussions, and Dr. Glenn Furuta for constructive advice. We thank Michael Eby for CCHMC pathology database and EGID database maintenance and queries. We thank Shawna Hottinger for editorial assistance.

Abbreviation

- EDP

EoE diagnostic panel

Footnotes

Author Contributions: MER obtained funding, provided conceptual platform and supervised the EDP study. MER and TW designed the experiments. TW performed the experiments, created the dual algorithms and analyzed the data. TW and MER wrote the paper. TW, EMS and KAK obtained the RNA samples from biopsies. TMG performed chart review for the MII-pH study. JPA, PEP, JPF, JMG, AK, JPK and MER provided clinical samples by EGD and joined constructive interim discussions. ECK reviewed the statistical methods used throughout the study. MHC provided pathological insight regarding the histological biopsy sections involved.

Disclosures: EMS, TMG, KAK, JPA, PEP, JPF, JMG, AK, ECK, MHC, JPK have no conflict of interest to disclose. MER serves as a consultant for Immune Pharmaceuticals and has an equity ownership; MER has a royalty from reslizumab, a drug being developed by Teva Pharmaceuticals. Both of these interests are not directly related to the present paper. MER and TW are co-inventors for a pending patent based on the EDP test described herein.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

- 1.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. quiz 21–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hruz P, Straumann A, Bussmann C, et al. Escalating incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis: a 20-year prospective, population-based study in Olten County, Switzerland. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1349–1350. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veerappan GR, Perry JL, Duncan TJ, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in an adult population undergoing upper endoscopy: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:420–6. 426 e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remedios M, Campbell C, Jones DM, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: clinical, endoscopic, histologic findings, and response to treatment with fluticasone propionate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupte AR, Draganov PV. Eosinophilic esophagitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:17–24. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, et al. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigo S, Abboud G, Oh D, et al. High intraepithelial eosinophil counts in esophageal squamous epithelium are not specific for eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:435–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, et al. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:536–47. doi: 10.1172/JCI26679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchard C, Mingler MK, McBride M, et al. Periostin facilitates eosinophil tissue infiltration in allergic lung and esophageal responses. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:289–96. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abonia JP, Blanchard C, Butz BB, et al. Involvement of mast cells in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:140–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulder DJ, Justinich CJ. Understanding eosinophilic esophagitis: the cellular and molecular mechanisms of an emerging disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:139–47. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Rodriguez-Jimenez B, et al. A striking local esophageal cytokine expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:208–17. 217 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Burwinkel K, et al. Coordinate interaction between IL-13 and epithelial differentiation cluster genes in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Immunol. 2010;184:4033–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenzl TG, Benninga MA, Loots CM, et al. Indications, methodology, and interpretation of combined esophageal impedance-pH monitoring in children: ESPGHAN EURO-PIG standard protocol. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:230–4. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182592b65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gusnanto A, Calza S, Pawitan Y. Identification of differentially expressed genes and false discovery rate in microarray studies. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18:187–93. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3280895d6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanchard C, Mingler MK, Vicario M, et al. IL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caldwell JM, Blanchard C, Collins MH, et al. Glucocorticoid-regulated genes in eosinophilic esophagitis: a role for FKBP51. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:879–888. e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravi K, Talley NJ, Smyrk TC, et al. Low grade esophageal eosinophilia in adults: an unrecognized part of the spectrum of eosinophilic esophagitis? Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1981–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1594-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeBrosse CW, Collins MH, Buckmeier Butz BK, et al. Identification, epidemiology, and chronicity of pediatric esophageal eosinophilia, 1982–1999. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.