Abstract

Adherence interventions are a recommended strategy to salvage failing antiretroviral therapy without regimen change. We assessed the durability of resuppression when using this approach. Of 300 patients who resuppressed on the same regimen (41% of all those with virologic failure), 148 (45%) remained suppressed during follow-up for a median of 2.4 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 1.1, 4.0). Resuppression can be durable following viremia without a switch in antiretroviral therapy regimen.

Background

One of the potential values of HIV RNA (viral load) monitoring, when used as part of a public health approach for antiretroviral therapy (ART), is to identify virologic failure early and implement adherence interventions to achieve HIV RNA suppression without a regimen change (Guidelines Development Group 2013). When virologic failure is identified sufficiently early, resuppression without regimen change is achieved in 41 to 70% of patients with a single HIV RNA >1000 c/mL, at least in the short-term (Orrell et al. 2007; Wilson et al. 2009; Pirkle et al. 2009; Hoffmann et al. 2009). However, many patients have HIV drug resistance mutations at the time of detection of viremia (Hoffmann et al. 2009; Marconi et al. 2008), potentially compromising durability and leading to rapid failure following resuppression. The phenomenon of transient suppression was first observed in early clinical trials of lower potency regimens (Gallant et al. 2005; Gulick et al. 1997; Rey et al. 2006; Walmsley et al. 2002). If resuppression after failure is transient little is gained by maintaining a current regimen and harm could occur if further resistance mutations develop or the CD4 count declines. We investigated the durability of resuppression while remaining on the same regimen after a first failure episode in a routine ART care cohort in South Africa.

Methods

Patients included in this study were enrolled in a previously described cohort from a workplace HIV program (Hoffmann et al. 2009). Briefly, they met the following criteria: initiated ART from November 2002 through May 2006, were ≥18 years old, were ART-naïve at ART initiation, received an ART regimen of zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz, and after an initial response to ART developed virologic failure (HIV RNA >1000 c/mL) and then subsequently re-suppressed (HIV RNA <400 c/mL) without a change in regimen (Hoffmann et al. 2009). We excluded all participants from the original study who failed to meet these criteria: those who remained suppressed during observation, 2425 of 3432 (71%); developed virologic failure but had no subsequent HIV RNA assays on a first-line regimen, 192; and developed failure but did not subsequently resuppress, 484 of 815 with failure and subsequent data (59%). This analysis focused on the 331 patients who resuppressed without a change in regimen (41% of the 815 with failures and subsequent data). We extended observation time until the earliest of change in ART regimen, loss from care, or November 2011. Of the 331 patients, 31 patients had no additional follow-up after the resuppression visit, thus they were excluded from further analysis. Among the 300 patients who resuppressed and had subsequent data, we assessed the durability of suppression by determining the time to repeat failure or last observed HIV RNA value while remaining suppressed. We defined virologic failure as a single HIV RNA >1000 c/mL without subsequent return to a value <400 c/mL while remaining on the same regimen (either a single value if no subsequent data or two consecutive values >1000 c/mL if multiple HIV RNA results). We included in the definition a single value >1000 c/mL because some patients had a regimen switch after a single elevated HIV RNA. We defined transient viremia as a single HIV RNA >400 c/mL with a subsequent HIV RNA <400 c/mL without a regimen switch. We defined adherence intervals as the time from first detection of failure to resuppression and the time extending up to 12 months following resuppression. We defined incomplete adherence during the interval as a self-report of one or more missed doses of ART during the three days prior to any of the clinic visits during the interval. Ethics approvals were provided by Johns Hopkins University and the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Adherence support within this HIV program followed a standardized protocol with individual patient-centered counseling prior to ART initiation (2 sessions) and immediately following ART initiation (1 – 2 sessions). Additional counseling (1 – 2 sessions) was triggered by laboratory confirmed treatment failure (HIV RNA >1000 c/mL), provider concern regarding inadequate adherence, or patient request. Treatment failure counseling followed a patient-centered approach directed at identifying and overcoming specific barriers to adherence. The counseling was time-limited and did not include additional support (monetary or otherwise). All counseling was provided by either trained adherence counselors or nurses.

We described the proportions with and without repeat failure and the duration of resuppression. We also described transient viremia and the resistance profile at the first failure on the first-line regimen when prior HIV drug resistance results were available. Duration of resuppression was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and associations with repeat viremia were assessed with Cox proportional hazards modeling. Chi-square testing was used to compare adherence between groups.

Results

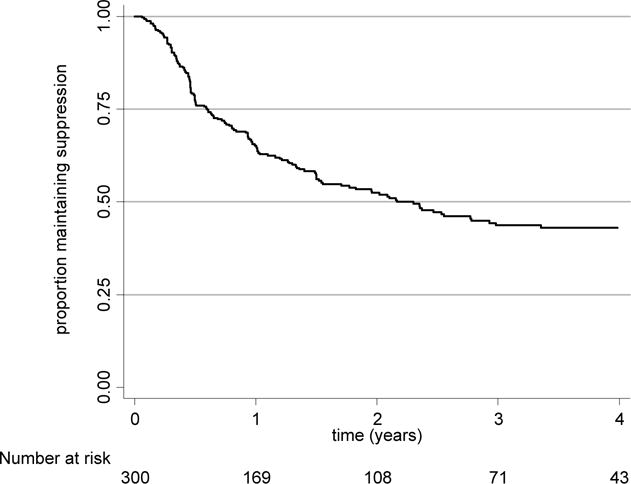

Of the 300 resuppressors with follow-up data, 276 (92%) were men; the median age and CD4 count at the time of resuppression were 48 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 42, 54) and 281 cells/mm3 (IQR: 178, 407), respectively. The median log10 HIV RNA at the time of first failure (prior to resuppression) was 4.3 c/mL (IQR: 3.6, 4.9). The median time to either end of follow-up or repeat failure was 1.1 years (IQR: 0.47, 2.5; Figure 1) from the time of resuppression. Resuppression without repeat failure occurred among 148 (49%) patients with a median follow-up time of 2.4 years (IQR: 1.1, 4.0). Thirty-nine (26%) experienced an episode of transient viremia. Another 152 patients (51%) had repeat virologic failure after a median of 0.63 years (IQR: 0.40, 1.4); 19 (12%) of whom experienced transient viremia before eventual failure. There were no differences in age, HIV RNA at first failure, or CD4 count among those with and without a second episode of failure (all p>0.1). During the interval from first failure to resuppression, 40 (27%) of those without repeat failure and 57 (38%) of those with repeat virologic failure reported at least one missed ART dose (p=0.06). During the interval after resuppression, 21 (14%) of those without repeat failure and 27 (18%) of those with repeat failure reported at least one missed dose (p=0.3).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plot of time to virologic failure, after resuppression without a switch in regimen

Genotypic HIV drug resistance data were available for 22 patients from prior studies. The distribution of drug resistance mutations was as follows: Among those with durable suppression (10 patients) one had an M184V/I and K103N, one an M184V/I and V106M, three a K103N only, one a V106M only, and four had no resistance. Among those with failure (12 patients), one had an M184V, K103N, and V106M; one a K103N and V106M; one a V106M and G190A; one a K103N and P225H; one a K103N only; one a V106M only; and 6 had no resistance mutations.

Discussion

Routine HIV RNA monitoring is a powerful tool for identifying lapses in adherence. In addition, HIV RNA monitoring had a clear advantage over self-reported adherence, a measure that we found to be minimally correlated with virologic failure, consistent with multiple prior reports of self-report for measuring adherence (McMahon et al. 2013; Peterson et al. 2013; Wagner & Rabkin 2000; Thirumurthy et al. 2012). When viremia is identified, resuppression can be achieved, especially when adherence interventions are implemented with a reported success of resuppression ranging from 41%, as we have observed (Hoffmann et al. 2009), to 53% and 70% reported from two other South African studies (Calmy et al. 2007; Orrell et al. 2007). However, despite endorsement of this approach by the World Health Organization (Guidelines Development Group 2013), durability had not been previously evaluated. We have demonstrated the longer-term success of this approach with a median duration of resuppression of more than one year.

Our rate of failure following resuppression was higher than that of primary failure (Barth et al. 2010). However the first episode of failure suggests adherence challenges, as a result this sub-group is at increased risk for repeat virologic failure (Johnston et al. 2012). In addition, accumulation of resistance mutations among some patients may increase the probability of viral rebound although our limited resistance data do not suggest that this is a major cause of viral rebound as 6 of the 12 with HIV genotyping data and viral rebound had no identified drug resistance mutations.

This analysis has the advantage of assessing outcomes in a routine care cohort. In addition, patients in this study received a standardized and simple to implement adherence counseling package. Limitations include missing data and variable duration of follow-up. An additional limitation is the small number of HIV drug resistance results, too few to be able to draw conclusions. The reason that we included these results is that we, and others, have observed resuppression despite resistance, but data on durability have been lacking (El-Khatib et al. 2011; Fox et al. 2008).

Our findings support using HIV RNA monitoring as a tool to select patients for targeted adherence interventions to achieve virologic suppression and to maintain patients on a first-line regimen. We also highlight limitations of self-reported adherence measures in predicting virologic suppression. The use of HIV RNA monitoring may improve outcomes over the lifetime of a patient by preventing clinical deterioration and by preserving regimens for future use.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants AI- K23 083099 and P30-AI094189-01A1 (CFAR).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors: None.

Contributor Information

Salome Charalambous, Email: scharalambous@auruminstitute.org.

Alison D Grant, Email: Alison.grant@lshtm.ac.uk.

Lynn Morris, Email: lynnm@nicd.ac.za.

Gavin J Churchyard, Email: gchurchyard@auruminstitute.org.

Richard E Chaisson, Email: rchaiss@jhmi.edu.

References

- Barth RE, van der Loeff MF, Schuurman R, Hoepelman AI, Wensing AM. Virological follow-up of adult patients in antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:155–166. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner K, Mezochow A, Roberts T, Ford N, Cohn J. Viral load monitoring as a tool to reinforce adherence: a systematic review. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829f05ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmy A, Ford N, Hirschel B, Reynolds SJ, Lynen L, Goemaere E, Garcia de la Vega F, Perrin L, Rodriguez W. HIV viral load monitoring in resource-limited regions: optional or necessary? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:128–134. doi: 10.1086/510073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Khatib Z, Delong AK, Katzenstein D, Ekstrom AM, Ledwaba J, Mohapi L, Laher F, Petzold M, Morris L, Kantor R. Drug resistance patterns and virus re-suppression among HIV-1 subtype C infected patients receiving non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in South Africa. J AIDS Clin Res. 2011;2 doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox Z, Phillips A, Cohen C, Neuhaus J, Baxter J, Emery S, Hirschel B, Hullsiek KH, Stephan C, Lundgren J. Viral resuppression and detection of drug resistance following interruption of a suppressive non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based regimen. AIDS. 2008;22:2279–2289. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328311d16f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant JE, Rodriguez AE, Weinberg WG, Young B, Berger DS, Lim ML, Liao Q, Ross L, Johnson J, Shaefer MS. Early virologic nonresponse to tenofovir, abacavir, and lamivudine in HIV-infected antiretroviral-naive subjects. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1921–1930. doi: 10.1086/498069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harries A, Hirnschall G, editors. Guidelines Development Group. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulick RM, Mellors JW, Havlir D, Eron JJ, Gonzalez C, McMahon D, Richman DD, Valentine FT, Jonas L, Meibohm A, Emini EA, Chodakewitz JA. Treatment with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and prior antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:734–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann CJ, Charalambous S, Sim J, Ledwaba J, Schwikkard G, Chaisson RE, Fielding KL, Churchyard GJ, Morris L, Grant AD. Viremia, resuppression, and time to resistance in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) subtype C during first-line antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1928–1935. doi: 10.1086/648444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston V, Fielding K, Charalambous S, Mampho M, Churchyard G, Phillips A, Grant AD. Second-line antiretroviral therapy in a workplace and community-based treatment programme in South Africa: determinants of virological outcome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marconi VC, Sunpath H, Lu Z, Gordon M, Koranteng-Apeagyei K, Hampton J, Carpenter S, Giddy J, Ross D, Holst H, Losina E, Walker BD, Kuritzkes DR. Prevalence of HIV-1 drug resistance after failure of a first highly active antiretroviral therapy regimen in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1589–1597. doi: 10.1086/587109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon JH, Manoharan A, Wanke CA, Mammen S, Jose H, Malini T, Kadavanu T, Jordan MR, Elliott JH, Lewin SR, Mathai D. Pharmacy and self-report adherence measures to predict virological outcomes for patients on free antiretroviral therapy in Tamil Nadu, India. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2253–2259. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0436-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrell C, Harling G, Lawn SD, Kaplan R, McNally M, Bekker LG, Wood R. Conservation of first-line antiretroviral treatment regimen where therapeutic options are limited. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson K, Menten J, Peterson I, Togun T, Okomo U, Oko F, Corrah T, Jaye A, Colebunders R. Use of Self-Reported Adherence and Keeping Clinic Appointments as Predictors of Viremia in Routine HIV Care in the Gambia. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2013 doi: 10.1177/2325957413500344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkle CM, Boileau C, Nguyen VK, Machouf N, Ag-Aboubacrine S, Niamba PA, Drabo J, Koala S, Tremblay C, Rashed S. Impact of a modified directly administered antiretroviral treatment intervention on virological outcome in HIV-infected patients treated in Burkina Faso and Mali. HIV Med. 2009;10:152–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey D, Krebs M, Partisani M, Hess G, Cheneau C, Priester M, Bernard-Henry C, de ME, Lang JM. Virologic response of zidovudine, lamivudine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate combination in antiretroviral-naive HIV-1-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:530–534. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000245885.74133.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirumurthy H, Siripong N, Vreeman RC, Pop-Eleches C, Habyarimana JP, Sidle JE, Siika AM, Bangsberg DR. Differences between self-reported and electronically monitored adherence among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in a resource-limited setting. AIDS. 2012;26:2399–2403. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359aa68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GJ, Rabkin JG. Measuring medication adherence: are missed doses reported more accurately then perfect adherence? AIDS Care. 2000;12:405–408. doi: 10.1080/09540120050123800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley S, Bernstein B, King M, Arribas J, Beall G, Ruane P, Johnson M, Johnson D, LaLonde R, Japour A, Brun S, Sun E. Lopinavir-ritonavir versus nelfinavir for the initial treatment of HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2039–2046. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D, Keiluhu AK, Kogrum S, Reid T, Seriratana N, Ford N, Kyawkyaw M, Talangsri P, Taochalee N. HIV-1 viral load monitoring: an opportunity to reinforce treatment adherence in a resource-limited setting in Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:601–606. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]