Abstract

Rice seedlings were inoculated with Azospirillum sp. B510 and transplanted into a paddy field. Growth in terms of tiller numbers and shoot length was significantly increased by inoculation. Principal-coordinates analysis of rice bacterial communities using the 16S rRNA gene showed no overall change from B510 inoculation. However, the abundance of Veillonellaceae and Aurantimonas significantly increased in the base and shoots, respectively, of B510-inoculated plants. The abundance of Azospirillum did not differ between B510-inoculated and uninoculated plants (0.02–0.50%). These results indicate that the application of Azospirillum sp. B510 not only enhanced rice growth, but also affected minor rice-associated bacteria.

Keywords: Azospirillum sp. B510, inoculation, rice paddy field, pyrosequencing, bacterial community

The genus Azospirillum, which includes nitrogen-fixing Gram-negative Alphaproteobacteria, has been known for many years to be composed of plant-growth-promoting bacteria. Among the Alphaproteobacteria, Azospirillum is one of the most studied genera (8). This genus was isolated not only from the rice phyllosphere (7, 17), but also from the rhizosphere of other plants (21). Rice growth was enhanced by inoculation with Azospirillum (15).

Azospirillum sp. strain B510 was isolated from surface-sterilized stems of field-grown rice (7). Rice tiller numbers and seed yield were significantly increased with B510 inoculation in paddy fields (13). Moreover, Yasuda et al. (26) showed that rice plants inoculated with B510 had greater resistance against two diseases caused by the virulent rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae and by the virulent bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae. Thus, Azospirillum sp. B510 is a promising bacterial inoculant for plant growth promotion and agricultural practices (13).

The plant-growth-promoting effects of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 were due to the production of indole-3-acetic acid (24). Azospirillum cells inoculated into rice plants often spread from below-ground roots into above-ground tissues (4). However, Azosprillium sp. B510 inoculation gave rise to colonization in basal parts of rice plants in a laboratory experiment (26). Little is known about the effect of Azospirillum sp. B510 inoculation on rice-associated bacterial communities in field conditions. The objective of the present study was to determine whether Azospirillum sp. B510 inoculation changes rice-associated bacterial communities, including the B510 inoculant, when the effects of inoculation first appear in a paddy field.

Although our previous study clearly indicated that Azospirillum sp. B510 tagged with the DsRed gene able to colonize endophytically in rice seedlings (12), we determined the initial colonization level of B510 carrying the plasmid pHC60 (3) in 7-day-old seedlings of Oryza sativa cv. Nipponbare (see supplementary material). For the field experiment, Azospirillum sp. B510 was cultured in nutrient broth (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) at 30°C for 16 h. A bacterial suspension (1×108 CFU mL−1) was prepared with distilled water. Three-week-old rice seedlings (Oryza sativa cv. Nipponbare) were inoculated with 500 mL of the bacterial suspension (final density: 1.5×106 CFU mL−1) on a tray containing 300 seedlings (Fig. S1). The seedlings were incubated in a greenhouse for 5 d in 2011 and then transplanted to Kashimadai experimental field (Tohoku University, Japan; 37°28′N, 141°06′E), which had been treated with nitrogen fertilizer (30 kg ha−1) (Fig. S1). Overall, 300 seedlings of each cultivar were planted in 3×4.5 m plot. Hills were spaced 30 cm apart. The soil chemical properties were as follows: pH, 5.2; total C content, 4.3%; total N content, 0.1%; Truog phosphorous, 74 mg P2O5 kg−1.

Plant growth (tiller number and shoot length) was measured 46 d after transplanting (DAT) (Fig. S1) (23). Rice plants were sampled at 51 DAT (Fig. S1). Shoot (above-ground plant tissues starting 10 cm above the root) and base (including 10 cm stem and 1 cm root) were separated (Fig. S2), because B510 cells colonized rice basal parts in laboratory experiments (26).

Three sets of composite samples including at least three rice plants were independently prepared for the bases or shoots (approximately 100 g each) in each treatment, and then stored at −80°C until used. The composite samples of bases or shoots were homogenized without surface sterilization to prepare shoot- and base-associated bacterial cells containing both endophytes and epiphytes. DNA was extracted by the bacterial enrichment method (11). Bacterial communities were analyzed by triplicate 454 pyrosequence analyses targeting the V2–V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene using 454 barcode tags (20). Raw pyrosequencing reads were processed using the Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) software package (2). The reads were assigned to each sample according to sample-specific barcodes. Low-quality reads with a length shorter than 300 bp, with an average quality score lower than 25, with mismatching primer sequences, or with ambiguous bases (denoted by N), were eliminated from downstream analyses. The forward and reverse primer sequences were removed from the quality-filtered reads. The remaining sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity. Taxonomic assignment of representative OTUs was performed using the RDP Classifier (25) with default parameters. Principal-coordinates analysis (PCoA) was performed using weighted UniFrac distances (14). The project number for 454 pyrosequence reads in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database is ID DRA000965.

Azospirillum sp. B510 inoculation significantly enhanced tiller numbers (by 8.6%) and shoot length (3.1%) as compared with uninoculated controls (t-test; P<0.05; n=25) (Fig. S3). This tiller number increase by B510 inoculation is similar to the results of a previous field experiment in Hokkaido, Japan (13).

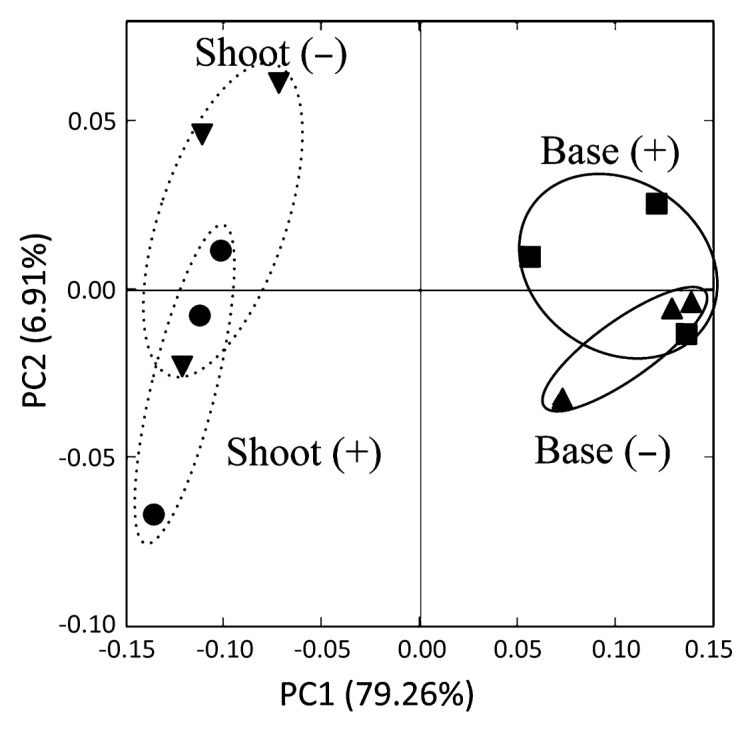

For bacterial communities, the total number of pyrosequence reads of 16S rRNA genes from base and shoot, with and without B510 inoculation, ranged from 16,156 to 33,906 (Table S1). Bacterial community structures were analyzed by PCoA (Fig. 1). PC1 (79.3%) showed that bacterial communities were separately clustered in the shoot and base. PC2 accounted for only 6.9% of the differences in microbial communities. There were no marked shifts in bacterial communities by B510 inoculation in either the shoot or base of the rice plants (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Principal-coordinates analysis (PCoA) of bacterial communities in the base and the shoot of rice plants with (+) and without (−) Azospirillum sp. B510 inoculation. ▼, Shoot without inoculation (control); ●, shoot with inoculation; ■, base with inoculation; ▲, base without inoculation (control). Broken line (---): microbial communities of shoot with and without Azospirillum sp. B510 inoculation; solid line (—): microbial communities of base with and without Azospirillum sp. B510 inoculation.

The compositions of entire bacterial communities are shown at the class level (Table S2) and with more detailed taxa (Order, Family and Genus) (Table 1). At the class level, inoculation significantly increased the relative (percent) abundance of the class Negativicutes (phylum Firmicutes) in the rice-plant base (P<0.05; t-test), although Alphaproteobacteria (>30% of total sequences) were the most abundant in both shoot and base communities (Table 1). In the Alphaproteobacteria, Rhizobium (relative abundance, 9.5–20.7%) and Methylobacterium (15.2–22.0%) were dominant bacterial groups in the rice tissue. However, their relative abundances were not significantly influenced by inoculation. In contrast, relatively minor bacterial groups were significantly influenced by B510 inoculation: the relative abundance of Aurantimonas increased significantly in the shoot (from 4.8% in controls to 6.3% in inoculated plants) and Methylocystis decreased in the base (from 5.0% to 2.9%) with B510 inoculation. Our result was partially consistent with the previous observation that application of Azosprillium brasilense strains as inoculants did not influence the dominant members of the endophytic microbial communities in the rice phyllosphere using PCR-DGGE (22). DGGE profiles of the bacterial community might limit our understanding because its resolution is relatively low. However, in this study, minor bacterial groups, such as Auriontimonas (4.8% of relative abundance), Methylocystis (5%) and members of Veillonellaceae (>1%), were significantly influenced by inoculation.

Table 1.

Relative abundance of the predominant bacterial taxa (as determined from 16S rRNA) in base and shoot of rice plants inoculated with Azospirillum sp. B510 (n=3 for each sample). Standard deviation is shown in parentheses.

| Taxa | Relative abundance (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Base | Shoot | |||

|

|

|

|||

| − | + | − | + | |

| Proteobacteria | 53.9 (3.7) | 56.0 (9.2) | 91.3 (1.6) | 91 (2.0) |

| Alphaproteobacteria | 38.4 (1.9) | 36.8 (6.2) | 55.7 (7.6) | 55.2 (3.1) |

| Rhizobiales | 33.5 (1.5) | 31.5 (4.3) | 47.5 (5.0) | 48.2 (3.1) |

| Rhizobium | 9.5 (1.4) | 12.6 (0.8) | 20.7 (8.3) | 16.3 (3.3) |

| Methylobacterium | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1) | 15.2 (1.5) | 22.0 (4.1) |

| Aurantimonas | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.03) | 4.8 (0.6) | 6.3* (1.0) |

| Methylocystis | 5.0 (0.4) | 2.9* (0.5) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.5 (1.0) |

| Sphingomonadales | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.3) | 4.3 (2.4) | 3.5 (0.7) |

| Betaproteobacteria | 7.4 (0.7) | 10.7 (2.2) | 21.0 (10.4) | 11.0 (4.8) |

| Burkholderiales | 6.9 (0.7) | 9.7 (2.1) | 21.0 (10.4) | 11.0 (4.8) |

| Gammaproteobacteria | 4.3 (3.9) | 4.6 (1.6) | 13.5 (6.2) | 22.9 (10.1) |

| Deltaproteobacteria | 1.1 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2) | 1.1 (1.2) |

| Others | 2.7 (0.4) | 3.1 (0.7) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.3) |

| Firmicutes | 10.6 (2.1) | 15.6 (4.5) | 2.9 (0.8) | 3.6 (1.5) |

| Negativicutes | 1.8 (0.4) | 3.3* (0.7) | <0.03 | <0.02 |

| Selenomonadales | 1.8 (0.2) | 3.3* (0.3) | <0.03 | <0.02 |

| Veillonellaceae | 1.4 (0.3) | 2.7* (0.5) | <0.03 | <0.02 |

| Bacilli | 5.6 (1.1) | 8.2 (4.5) | 2.7 (0.7) | 3.4 (1.4) |

| Clostridia | 3.2 (1.0) | 4.1 (1.7) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) |

| Cyanobacteria | 14.0 (0.9) | 10.0 (2.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.2) |

| Planctomycetes | 4.7 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.2) |

Asterisks indicate a significant difference (P<0.05; t-test) between uninoculated controls (−) and inoculated plants (+). Data for bacterial taxa with low relative abundance (<1%) are not shown. Grey areas highlight the taxa with relative abundance, significantly different between inoculated and uninoculated rice plants.

Aurantimonas has been found in above-ground parts of plants such as rice, soybean, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Jatropha curcas (1, 5, 16, 18). Their population was likely controlled in a manner similar to that of legume-rhizobia symbiosis (10). These findings suggest that Aurantimonas spp. are ubiquitous in the phyllosphere and have close interactions with plants. Veillonellaceae is a single family of anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria within Firmicutes, unlike most other members of the Firmicutes (19). Members of Veillonellaceae have been detected from the human gut and from rice paddy soil (6, 9). Hooda et al. (9) observed that consumption of soluble corn fiber led to increases in Veillonellaceae in the gut of healthy men. Thus, it is likely that the members of Aurantimonas and Veillonellaceae are associated with higher organisms, although their biology is largely unknown. Thus, the limited knowledge of bacterial functions makes it difficult to discuss the relationships between the bacterial community and rice growth promotion, although it is possible that growth enhancement was induced by minor bacterial changes.

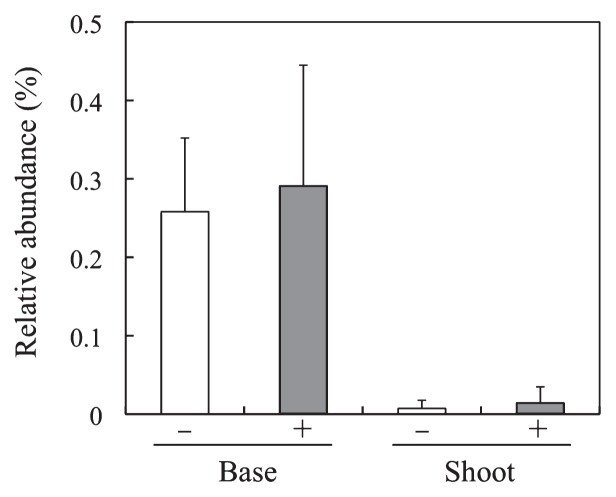

In the present study, the B510 inoculant and natural Azospirillum populations were not differentiated because of the limitation of the pyrosequence read length (approximately 400–500 bp). However, it is possible to estimate the fate of the inoculant during rice growth in the field by observing the fluctuation of Azospirillum abundance. The relative abundance of Azospirillum was not significantly influenced by B510 inoculation, although it was low (0.02–0.5%) in both the base and shoot (Fig. 2), suggesting that the abundance of the B510 inoculant decreased at least to that of natural Azospirillum populations at 51 DAT (Fig. S1). Apart from the inoculation effect, the relative abundance of Azospirillum was higher in the base (0.26–0.29%) than in the shoot (0.02–0.04%) (Fig. 2). The initial bacterial community was not determined at 0 DAT in this field experiment. However, 5.9×104 CFU per plant of Azospirillum sp. B510 (0.6% of total inoculant of 106) was detected from surface-sterilized plant tissue in the present study, suggesting that Azospirillum sp. B510 cells colonized in rice tissue as endophytes just after 0 DAT.

Fig. 2.

Relative abundance of Azospirillum spp. in the rice plant’s base and shoot with (+) and without (−) Azospirillum sp. B510 inoculation.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that B510 inoculation significantly influenced minor bacterial groups of the shoot and base of rice plants, but not major bacterial groups. These results indicate that Azospillium sp. B510 inoculation not only stimulated rice growth, but also affected relatively minor rice-associated bacteria in the rice base and shoot.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Development of Mitigation and Adaptation Techniques to Global Warming, and Genomics for Agricultural Innovation, PMI-0002 and BRAIN), and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) 23248052 and for Challenging Exploratory Research 23658057 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

References

- 1.Anda M, Ikeda S, Eda S, Okubo T, Sato S, Tabata S, Mitsui H, Minamisawa K. Isolation and genetic characterization of Aurantimonas and Methylobacterium strains from stems of hypernodulated soybeans. Microbes Environ. 2011;26:172–180. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.me10203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Meth. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng HP, Walker GC. Succinoglycan is required for initiation and elongation of infection threads during nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5183–5191. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5183-5191.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chi F, Shen S-H, Cheng H-P, Jing Y-X, Yanni YG, Dazzo FB. Ascending migration of endophytic rhizobia, from roots to leaves, inside rice plants and assessment of benefits to rice growth physiology. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7271–7278. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7271-7278.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delmotte N, Knief C, Chaffron S, Innerebner G, Roschitzki B, Schlapbach R, von Mering C, Vorholt JA. Community proteogenomics reveals insights into the physiology of phyllosphere bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16428–16433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905240106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doi T, Abe J, Shiotsu F, Morita S. Study on rhizosphere bacterial community in lowland rice grown with organic fertilizers by using PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Plant Root. 2011;5:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elbeltagy A, Nishioka K, Suzuki H, Sato T, Sato Y, Morisaki H, Mitsui H, Minamisawa K. Isolation and characterization of endophytic bacteria from wild and traditionally cultivated rice varieties. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2000;46:617–629. [Google Scholar]

- 8.García de Salamone IE, Funes JM, Di Salvo LP, Escobar-Ortega JS, D’Auria F, Ferrando L, Fernandez-Scavino A. Inoculation of paddy rice with Azospirillum brasilense and Pseudomonas fluorescens: Impact of plant genotypes on rhizosphere microbial communities and field crop production. Appl Soil Ecol. 2012;61:196–204. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooda S, Boler BMV, Serao MCR, Brulc JM, Staeger MA, Boileau TW, Dowd SE, Fahey GC, Swanson KS. 454 Pyrosequencing reveals a shift in fecal microbiota of healthy adult men consuming polydextrose or soluble corn fiber. J Nutr. 2012;142:1259–1265. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.158766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda S, Anda M, Inaba S, et al. Autoregulation of nodulation interferes with impacts of nitrogen fertilization levels on the leaf-associated bacterial community in soybeans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:1973–1980. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02567-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikeda S, Kaneko T, Okubo T, et al. Development of a bacterial cell enrichment method and its application to the community analysis in soybean stems. Microb Ecol. 2009;58:703–714. doi: 10.1007/s00248-009-9566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeda S, Okubo T, Anda M, et al. Community- and genome-based views of plant-associated bacteria: plant-bacterial interactions in soybean and rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:1398–1410. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isawa T, Yasuda M, Awazaki H, Minamisawa K, Shinozaki S, Nakashita H. Azospirillum sp. strain B510 enhances rice growth and yield. Microbes Environ. 2010;25:58–61. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.me09174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lozupone C, Knight R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8228–8235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucy M, Reed E, Glick B. Applications of free living plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2004;86:1–25. doi: 10.1023/B:ANTO.0000024903.10757.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madhaiyan M, Hu CJ, Jegan RJ, Kim SJ, Weon HY, Kwon SW, Ji L. Aureimonas jatrophae sp. nov. and Aureimonas phyllosphaerae sp. nov., two novel leaf-associated bacteria isolated from Jatropha curcas L. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;63:1702–1708. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.041020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mano H, Morisaki H. Endophytic bacteria in the rice plant. Microbes Environ. 2008;23:109–117. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.23.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mano H, Tanaka F, Nakamura C, Kaga H, Morisaki H. Culturable endophytic bacterial flora of the maturing leaves and roots of rice plants (Oryza sativa) cultivated in a paddy field. Microbes Environ. 2007;22:175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchandin H, Teyssier C, Campos J, Jean-Pierre H, Roger F, Gay B, Carlier J-P, Jumas-Bilak E. Negativicoccus succinicivorans gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from human clinical samples, emended description of the family Veillonellaceae and description of Negativicutes classis nov., Selenomonadales ord. nov. and Acidaminococcaceae fam. nov. in the bacterial phylum Firmicutes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:1271–1279. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.013102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okubo T, Ikeda S, Yamashita A, Terasawa K, Minamisawa K. Pyrosequence read length of 16S rRNA gene affects phylogenetic assignment of plant-associated bacteria. Microbes Environ. 2012;27:204–208. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME11258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng G, Wang H, Zhang G, Hou W, Liu Y, Wang ET, Tan Z. Azospirillum melinis sp. nov., a group of diazotrophs isolated from tropical molasses grass. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:1263–1271. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raúl OP, Carlos HB, Silvia Carrizo de B, Paulo Marcos Fernandes Boa S, Kátia Regina dos Santos T. Azospirillum inoculation and nitrogen fertilization effect on grain yield and on the diversity of endophytic bacteria in the phyllosphere of rice rainfed crop. Eur J Soil Biol. 2009;45:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sasaki K, Ikeda S, Eda S, et al. Impact of plant genotype and nitrogen level on rice growth response to inoculation with Azospirillum sp. strain B510 under paddy field conditions. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2010;56:636–644. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spaepen S, Dobbelaere S, Croonenborghs A, Vanderleyden J. Effects of Azospirillum brasilense indole-3-acetic acid production on inoculated wheat plants. Plant Soil. 2008;312:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naïve bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yasuda M, Isawa T, Shinozaki S, Minamisawa K, Nakashita H. Effects of colonization of a bacterial endophyte, Azospirillum sp. B510, on disease resistance in rice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73:2595–2599. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.