Abstract

Owing to its labile nature, a new role for cysteine sulfenic acid (-SOH) modification has emerged. This oxidative modification modulates protein function by acting as a redox switch during cellular signaling. The identification of proteins that undergo this modification represents a methodological challenge, and its resolution remains a matter of current interest. The development of strategies to chemically modify cysteinyl-containing peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis has increased significantly within the past decade. The method of choice to selectively label sulfenic acid is based on the use of dimedone or its derivatives. For these chemical probes to be effective on a proteome-wide level, their reactivity toward -SOH must be high to ensure reaction completion. In addition, the presence of an adduct should not interfere with electrospray ionization, the efficiency of induced dissociation in MS/MS experiments, or with identification of Cys-modified peptides by automated database searching algorithms. Herein, we employ a targeted proteomics approach to study the electrospray ionization and fragmentation effects of different –SOH specific probes, and compared them to commonly used alkylating agents. We then extend our study to a whole proteome extract using shotgun proteomic approaches. These experiments enable us to demonstrate that dimedone adducts do not interfere with electrospray by suppressing the ionization nor impedes product ion assignment by automated search engines, which detect a + 138 Da increase from unmodified peptides. Collectively, these results suggest dimedone can be a powerful tool to identify sulfenic acid modifications by high-throughput shotgun proteomics of a whole proteome.

Keywords: redox proteomics, sulfenic acid, dimedone, cysteine modifiers, electrospray ionization (ESI)

Introduction

Reactive oxidant species derived from oxygen (ROS) or nitrogen (RNS) have been known from a chemical point of view for more than 30 years, and their biological importance has become increasingly apparent since their discovery. Many physiological and pathological conditions are correlated with the accumulation of these RNOS, leading to modifications of DNA, proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids[1]. The discovery of regulatory switches mediated by reversible thiol oxidation in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes has established a fundamental role of cysteine thiols in biological systems[2, 3], providing a versatile mechanism to modulate cellular processes[4], and establishing a new paradigm for signal transduction[5, 6]. Cysteine modifications are considered one of the most relevant oxidative post-translational modifications (oxPTMs) because they have extensively been shown to play roles in protein folding, enzymatic modulation, and signal transduction[7]. In addition to the well-known and studied disulfide bridge (-S-S-) formation[8], protein thiols (-SH) can undergo a broad range of oxidative modifications such as sulfenic acid (-SOH), which is the first cysteine oxoform generated upon reaction of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) with a protein thiol[9, 10]. Due to its significant role in cellular signaling[11] and implications in human diseases such as atherosclerosis[12], diabetes[13], or cancer[14], there is a growing interest within the scientific community to develop tools that specifically react with –SOH to facilitate identification of protein targets susceptible to oxidation. The most widely used strategy for detection of sulfenic acid- modified proteins is based on the chemoselective reactivity of dimedone (5,5-dimethyl-1,3-cyclohexanedione), which forms an irreversible adduct with –SOH (Fig.1, scheme 1) and was first described in 1974 by Allison and colleagues[15]. Since then, dimedone-based chemical probes have been developed to specifically label sulfenic acid, some of them incorporating a fluorescent- or biotin-conjugated reporter tag for analysis[16, 17], but no sulfenylome study of the whole proteome has been performed to date.

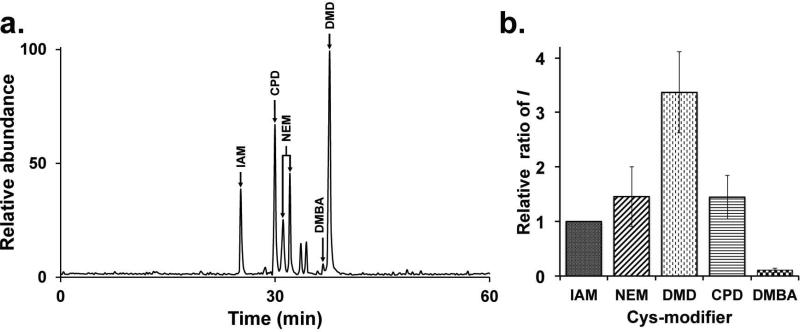

Figure 1.

Ionization of the YCVQQLK peptide labeled with the different alkylating agents or nucleophiles. (a.) Ion chromatogram obtained by ESI-linear ion trap. (b.) Average relative intensity ratio of the different species of the peptide taking IAM as reference. Error bars, mean ± s.e.m.

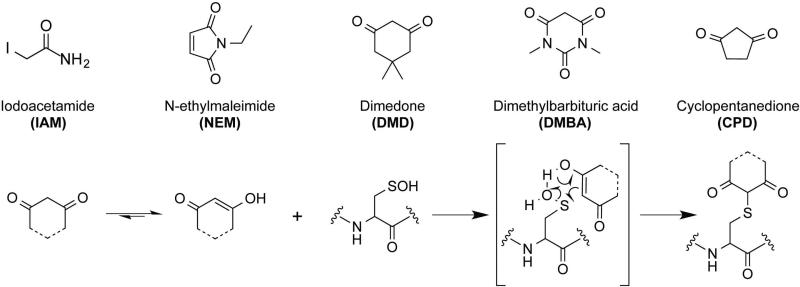

Scheme 1.

Structure of the different alkylating agents or carbon nucleophiles used in this study and electrophilic reaction of sulfenic acid-modified Cys with dimedone and its derivatives.

Redox proteomics is defined as the toolset used for detection and quantification of oxPTMs that modulate the proteome under oxidative stress or physiological signaling. The continued development of techniques to probe oxPTMs will further establish the physiological scope of cysteine oxidation and yield clues to uncover its molecular mechanisms. In the last decade, numerous proteomics strategies have been developed[18, 19], but redox proteomics still remains a technical challenge, mainly due to the labile nature of some thiol-redox modifications, the lack of mass spectrometry compatible tools to directly detect these modified residues, and the relatively late development of highly sensitive analytical instruments. Although this is an active area of research, the use of mass spectrometry in the study of sulfenylome has been limited to targeted proteins[20-23], and the great majority of high-throughput proteomics strategies in the literature have been applied to the identification and quantification of oxidized Cys without differentiating between specific oxoforms[24-28]. Some authors argue that this is mainly due to ionization suppression of the dimedone-based probes[29], but no studies have been performed to validate these statements to date.

Herein, we present a comparative study under electrospray (ESI) conditions between three –SOH specific chemical probes: 1) dimedone (DMD), 2) cyclopentanedione (CPD), and 3) dimethylbarbituric acid (DMBA). The utility of these sulfenic acid-specific probes with respect to MS analysis is directly correlated to null or minimum effects on ionization and negligible influence on peptide fragmentation without interfering with identification using database search engines. To further characterize the behavior of sulfenic acid probes under ESI-ionization conditions coupled to CID fragmentation and their effect on ionization efficiency, we investigated the ionization and fragmentation behavior of a synthetic heptapeptide modified with different carbon-nucleophiles (DMD, CPD and DMBA) and compared these results the behavior of iodoacetamide (IAM) and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), two commonly used alkylating agents to cap free thiols[30]. We then extended our studies to single protein models (bovine serum albumin and glutathione peroxidase Gpx3 from yeast), and ultimately applied our findings to a whole protein extract from A431 cells to identify sulfenic acid sites.

Results and discussion

Enhanced ionization efficiency for DMD.- Synthetic peptide study

We first analyzed the effect of three different carbon nucleophiles (DMD, CPD and DMBA) on the ionization of a model peptide modified with each compound and compared them to two of the most commonly used Cys-modifiers IAM and NEM (Figure 1). The synthetic peptide used in this study, YCVQQLK from bovine hsp90-alpha, was chosen on the basis of a previous work in which the peptide was identified both by IAM- and NEM-adducts[28]. Figure 2a shows the representative ion chromatogram of the heptapeptide labeled with the different reagents mentioned above; whereby equal amounts of peptide (200 fmol) was mixed prior to analysis. Because each peptide was synthetized individually using a large excess of nucleophile, unmodified peptides were not observed by LC-MS in any case (Supplementary Figures 2-6). The nature of each peak was determined by selected MS/MS ion monitoring (SMIM) using an HPLC-linear ion trap mass spectrometer[31, 32]. The detector was programmed to perform multiple fragmentations on doubly charged precursors ions [M + 2H]2+ corresponding to the YCVQQLK peptide modified with IAM, NEM, DMD, DMBA or CPD (m/z 453.8, 503.8, 510.3, 489.2 and 518.1 respectively). By monitoring the fragmentation of different precursor ions (Supplementary Figures 7-12) enabled us to assign the identity of each peak. It is important to note that during the fragmentation process, some fragment ions exhibited the loss of the probe, which is probably due to the formation of dehydroalanine[33]. As seen in the ion chromatogram (Figure 2a), DMD and CPD exhibited higher or similar peak intensities, respectively, than IAM and NEM. In counterpart, DMBA showed a negative influence on ionization resulting in the lowest peak intensity. Note that NEM-modified peptide eluted in two peaks, most likely due to the fact that NEM contains a prochiral center that can generates two stereoisomers with slightly different elution patterns[34].

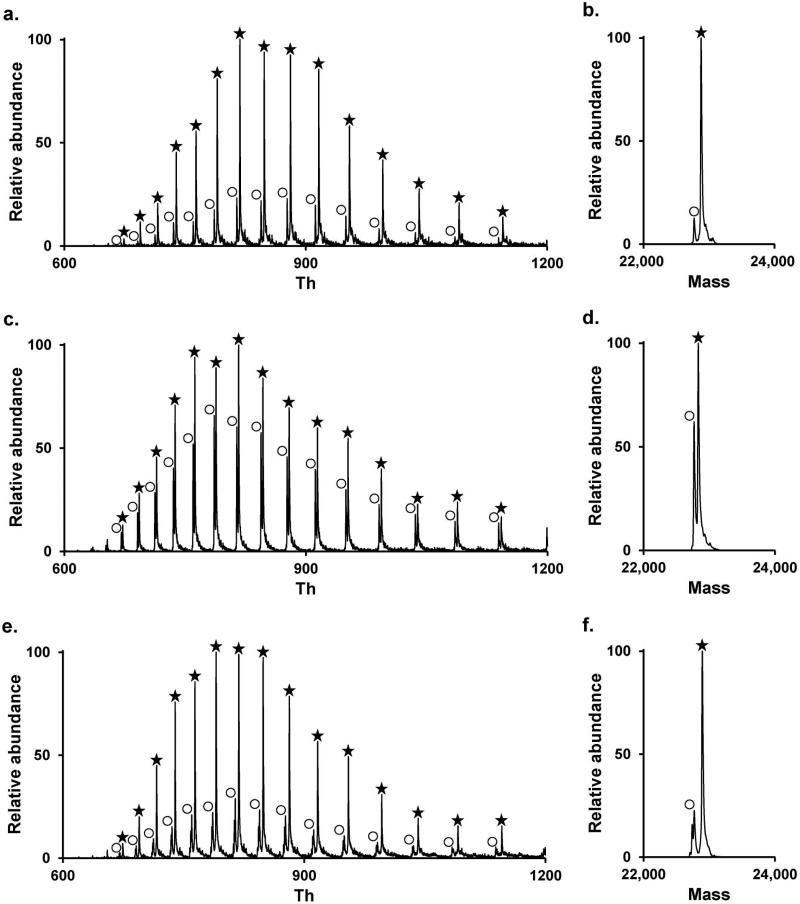

Figure 2.

Intact protein mass spectrometry analysis of Gpx3 labeled with different carbon nucleophiles in the presence of 1.5 Eq of H2O2. (a.–b.) DMDlabeled Gpx3 corresponding to a molecular weight of 22 879 Da. (c.–d.) CPD-labeled Gpx3 corresponding to a molecular weight of 22 834 Da. (e.–f.) DMBA-labeled Gpx3 corresponding to a molecular weight of 22 895 Da. (a., c., e.) Positive ion ESI mass spectra. (b., d., f.) Deconvoluted mass. White circles (◯) correspond to Gpx3-SO2H and black stars (٭) to Gpx3 nucleophile.

The analysis was performed in triplicate and the intensities were averaged for each of the modified peptides (Supplementary Table 1). Relative average intensity ratios were calculated by normalizing to IAM, and are summarized in Figure 2b. Significant ionization enhancement was observed with respect to DMD modification whereby the signal increased by more than 3-fold for DMD, and 1.2-fold for both NEM and CPD. Ionization is inhibited by 10-fold for peptide labeled with DMBA. We speculate aromatization by resonance of the compound during mass spectrometry analysis induces this observation (Supplementary Figure 13). Polar resonance forms of this compound are stabilized by their aromatic character, which could allow it to form strong ion pairs with analytes in solution and ultimately suppress ionization. Another mechanism could rely on DMBA-peptide aggregation by the presence of charges in the polar resonance forms at higher concentrations as a result of solvent evaporation in the sprayed solution[35], leading to signal suppression. None of the other nucleophiles (DMD, CPD) used in our studies can be aromatized and thus, are not subject to the possible effect of zwitterion species.

Protein identification.- BSA

In biological systems, sulfenic acids are unstable and highly reactive functional groups, resulting in the formation of other reversible, such as S-glutathionylation and disulfide bond formation, or irreversible (sulfinic and sulfonic acids) oxidation states[36]. The microenvironment of the Cys-SOH can stabilized the sulfenic acid, but sample manipulation for proteomics studies impedes the direct detection of a mass increase of 16 amu. Due to the transient nature of sulfenic acid modification, it is crucial to quickly trap the modified cysteines by the formation of a stable adduct that can be easily identified by mass spectrometry. In order to determine if the results obtained with the synthetic peptide model were not peptide-specific and can be extrapolated to routine proteomics studies, we examined the behavior of these nucleophiles towards a commercial protein, bovine serum albumin (BSA), which contains 35 Cys-residues and provides us a good high-throughput like model. BSA was in-gel reduced by DTT and treated with an excess of alkylating agents (IAM or NEM) or thiol-reactive versions of the nucleophiles. These compounds were obtained by the inserting a bromine at the 2-position of the ring generating Br-DMD, Br-CPD and Br-DMBA (Supplementary Figure 14)[37]. The adduct formation results on an increase of the mass of the cysteine of 57.04 (IAM), 125.05 (NEM), 138.06 (DMD), 96.02 (CPD), and 154.03 Da (DMBA). Table 1 lists the peptides identified under all conditions by SEQUEST algorithm at FDR = 1 %, using the probability ratio method[38], after in-gel digestion of a SDS-PAGE gel band containing 5 μg of BSA. 9 fmol were analyzed using a massive identification method in which automatic ion selection from the survey scan was performed on the 10 most intense ions[31]. It is important to note here that the number of non Cys-containing peptides was similar for all the samples, indicating the probes used in our study did not affect the digestion efficiency (Table 1). The highest number of alkylated-Cys peptides was identified as a result of IAM treatment (36 peptides), whereas 25 peptides were identified with NEM adduct. These results correlates with a previous study published by Zabet-Moghaddam et al. wherein they performed a similar comparative study in combination with MALDI ionization[39].

| # | Position | Sequence | MC | Cys | ø | IAM | NEM | Br-DMD | Br-CPD | Br-DMBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35-44 | FKDLGEEHFK | 1 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 2 | 37-44 | DLGEEHFK | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | |||

| 3 | 45-65 | GLVLIAFSQYLQQCPFDEHVK | 0 | 1 | • | • | ||||

| 4 | 66-75 | LVNELTEFAK | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 5 | 76-88 | TCVADESHAGCEK | 0 | 1 | • | • | • | • | ||

| 6 | 89-100 | SLHTLFGDELCK | 0 | 1 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 7 | 101-117 | VASLRETYGDM*ADCCEK | 1 | 2 | • | |||||

| 8 | 106-130 | ETYGDM*ADCCEKQEPERNECFLSHK | 2 | 3 | • | • | ||||

| 9 | 106-122 | ETYGDMADCCEKQEPER | 1 | 2 | • 1 | • 1 | ||||

| 10 | 106-117 | ETYGDMADCCEK | 0 | 2 | • 1 | • 1 | ||||

| 11 | 118-138 | QEPERNECFLSHKDDSPDLPK | 2 | 1 | • | • | • | • | • | |

| 12 | 123-138 | NECFLSHKDDSPDLPK | 1 | 1 | • | • | • | • | • | |

| 13 | 131-138 | DDSPDLPK | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | |

| 14 | 139-151 | LKPDPNTLCDEFK | 0 | 1 | • | • | • | • | • | |

| 15 | 139-155 | LKPDPNTLCDEFKADEK | 1 | 1 | • | • | • | • | • | |

| 16 | 141-151 | PDPNTLCDEFK | 0 | 1 | • | |||||

| 17 | 141-155 | PDPNTLCDEFKADEK | 1 | 1 | • | • | • | |||

| 18 | 168-183 | RHPYFYAPELLYYANK | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 19 | 169-183 | HPYFYAPELLYYANK | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 20 | 184-197 | YNGVFQECCQAEDK | 0 | 2 | • | • | • | • | ||

| 21 | 184-204 | YNGVFQECCQAEDKGACLLPK | 1 | 3 | • | • | ||||

| 22 | 198-204 | GACLLPK | 0 | 1 | • | |||||

| 23 | 242-248 | LSQKFPK | 0 | 0 | • | • | ||||

| 24 | 249-256 | AEFVEVTK | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 25 | 249-263 | AEFVEVTKLVTDLTK | 1 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | |

| 26 | 257-263 | LVTDLTK | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | |||

| 27 | 264-280 | VHKECCHGDLLECADDR | 1 | 3 | • | • | • | |||

| 28 | 264-285 | VHKECCHGDLLECADDRADLAK | 2 | 3 | • | • | • | |||

| 29 | 267-280 | ECCHGDLLECADDR | 0 | 3 | • | • | ||||

| 50 | 267-285 | ECCHGDLLECADDRADLAK | 1 | 3 | • | • | ||||

| 31 | 286-297 | YICDNQDTISSK | 0 | 1 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 32 | 298-309 | LKECCDKPLLEK | 1 | 2 | • | • | • | • | ||

| 33 | 300-309 | ECCDKPLLEK | 0 | 2 | • | |||||

| 34 | 310-318 | SHCIAEVEK | 0 | 1 | • | • | • | • | ||

| 35 | 310-336 | SHCIAEVEKDAIPENLPPLTADFAEDK | 1 | 1 | • | • | • | |||

| 36 | 319-336 | DAIPENLPPLTADFAEDK | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 37 | 319-340 | DAIPENLPPLTADFAEDKDVCK | 1 | 1 | • | • | • | • | ||

| 38 | 341-359 | NYQEAKDAFLGSFLYEYSR | 1 | 0 | • | |||||

| 39 | 347-359 | DAFLGSFLYEYSR | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 40 | 360-371 | RHPEYAVSVLLR | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 41 | 361-371 | HPEYAVSVLLR | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | |

| 42 | 375-386 | EYEATLEECCAK | 0 | 2 | • | • | • | |||

| 43 | 375-399 | EYEATLEECCAKDDPHACYSTVFDK | 1 | 3 | • | • | • | |||

| 44 | 387-399 | DDPHACYSTVFDK | 0 | 1 | • | • | • | • | • | |

| 45 | 387-401 | DDPHACYSTVFDKLK | 1 | 1 | • | • | • | |||

| 46 | 402-412 | HLVDEPQNLDC | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 47 | 413-433 | QNCDQFEKLGEYGFQNALIVR | 1 | 1 | • | • | • | |||

| 48 | 421-433 | LGEYGFQNALIVR | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 49 | 437-451 | KVPQVSTPTLVEVSR | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 50 | 438-451 | VPQVSTPTLVEVSR | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 51 | 456-468 | VGTRCCTKPESER | 1 | 2 | • | • | ||||

| 52 | 460-468 | CCTKPESER | 0 | 2 | • | |||||

| 53 | 469-482 | MPCTEDYLSLILNR | 0 | 1 | • | • 1 | • 1 | • 1 | • 1 | |

| 54 | 483-489 | LCVLHEK | 0 | 1 | • | • | • | • | • | |

| 55 | 496-507 | VTKCCTESLVNR | 1 | 2 | • | • | ||||

| 56 | 499-507 | CCTESLVNR | 0 | 2 | • | • | • | • | ||

| 57 | 508-523 | RPCFSALTPDETYVPK | 0 | 1 | • | • | • | • | • | |

| 5S | 509-523 | PCFSALTPDETYVPK | 0 | 1 | • | • | ||||

| 59 | 524-544 | AFDEKLFTFHADICTLPDTEK | 0 | 1 | • | |||||

| 60 | 529-544 | LFTFHADICTLPDTEK | 0 | 1 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| 61 | 549-558 | KQTALVELLK | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | |

| 62 | 569-580 | TVMENFVAFVDK | 0 | 0 | • 1 | • 1 | • 1 | • 1 | • 1 | • 1 |

| 63 | 569-597 | TVMENFVAFVDKCCAADDKEACFAVEGPK | 2 | 3 | • 1 | |||||

| 64 | 581-597 | CCAADDKEACFAVEGPK | 1 | 3 | • | • | ||||

| 65 | 588-597 | EACFAVEGPK | 0 | 1 | • | |||||

| 66 | 598-607 | LVVSTQTALA | 0 | 0 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| # of peptides identified | 32 | 58 | 42 | 45 | 49 | 27 | ||||

| # of non-Cys containing peptides identified | 19 | 22 | 17 | 19 | 21 | 19 | ||||

| # of Cys containing peptides identified | 13 | 36 | 25 | 26 | 28 | 8 | ||||

: peptide also ideintified with oxidized methionine

MC: missed cleavage

A total of 26 DMD-peptides were identified, whereas 28 peptides were identified with CPD. Although DMD showed a 2.5-fold increase in the ionization efficiency of the heptapeptide in comparison to CPD (Figure 1b), this effect was found to have no influence in this high-throughput like experiment as the number of identified peptides was similar between the two probes. This effect probably depends on the nature of the peptides (e.g., composition of amino acids and length). Only 8 Cys-peptides were identified with DMBA modification, representing the smallest number of Cys-containing peptides, and was lower than the number of peptides identified in the non-treated sample (Table 1). These results allowed us to conclude to an inhibitory effect on ESI ionization of DMBA, as reflected by the low number of DMBA-modified peptides identified, and confirms our results from the heptapeptide model. The low number of DMBA-peptides identified could also be due to inefficient in-gel labeling with Br-DMBA, but reactivity studies performed on a sulfenic acid tripeptide model indicate that the reaction with DMBA is slightly faster than DMD (V. Gupta and K. Carroll, manuscript in preparation).

Protein identification.- Gpx3 as –SOH model

The ultimate goal to designing effective –SOH chemoselective probes is to develop compounds that are capable of trapping sulfenic acid modifications in vivo and result in a stable adduct that can be identified by mass spectrometry. To test the ability of DMD, CPD and DMBA to trap sulfenic acids and its ability to undergo subsequent mass spectrometry analysis, we used as a double mutant (C64S C82S) of recombinant glutathione peroxidase Gpx3 from yeast, referred to hereafter as Gpx3[40]. It is known that in the presence of H2O2, the catalytic cysteine Cys36, is oxidized to sulfenic acid[41]. The intact mass of unmodified mutant Gpx3 was determined by LC- MS to be 22741 Da, which is in accordance to previously reported data by our group [41]. Next, we confirmed the mass of DMD-, CPD- and DMBA-labeled Gpx3 by LCMS after incubation of the protein with the different probes in presence of 1.5 eq. of H2O2. The molecular weights were determined to be 22879, 22834 and 22895 Da for the DMD-, CPD- and DMBA-adduct respectively, and confirmed that Gpx3-SOH was successfully labeled with the probes (Figure 3). Formation of sulfinic acid was also observed as previously reported[37, 41], and mainly corresponds to unreacted sulfenic acid that is over-oxidized during sample manipulation. Labeling is nearly stoichiometric for DMD and DMBA, whereas the reactivity of CPD appeared to be slower since the concentration of sulfinic acid-modified protein was similar to the concentration of CPD-protein (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

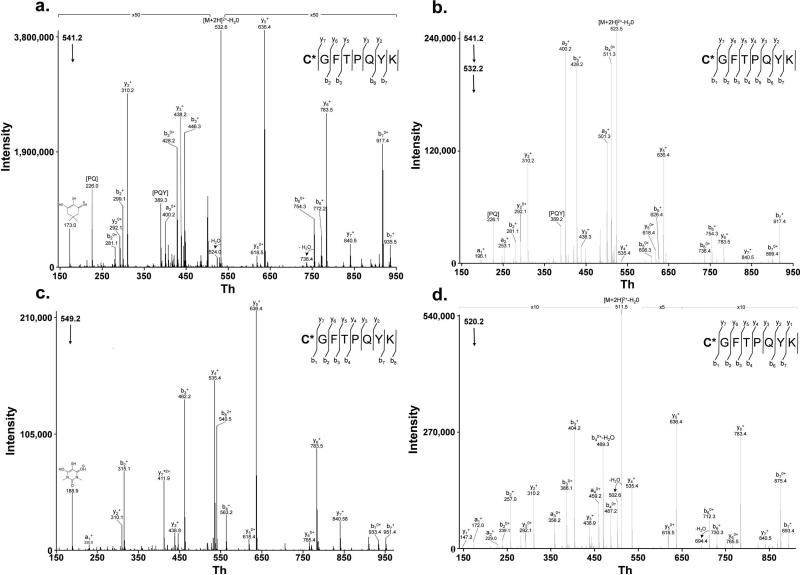

Identification of the CGFTPQYK peptide from Gpx3 labeled with the different probes tested. (a.) MS/MS fragment spectrum corresponding to the DMD-modified peptide. (b.) MS3 fragment spectrum corresponding to the DMD-modified peptide: this spectrum was obtained from the doubly charged precursor from (a.) with loss of a H2O molecule. (c.) MS/MS fragment spectrum corresponding to the DMBA-modified peptide. (d.) MS/MS fragment spectrum corresponding to the CPD-modified peptide. Fragments corresponding to the loss of internal amino acids from b ions are indicated with the same nomenclature used previously.

It was important to determine if treatment of Gpx3 with different carbon-nucleophiles could specifically trap Cys36–SOH, or if the increase in mass detected by LC-MS was due to the modification of another residue. This was accomplished by SMIM on labeled Gpx3 using an HPLC-linear ion trap mass spectrometer as described previously. The detector was programmed to perform multiple fragmentations on the ions 541.2, 549.2 and 520.2 corresponding to DMD-, DMBA- and CPD-modified cysteine form of the tryptic peptide C36GFTPQYK from Gpx3 respectively. By monitoring the fragmentation of the precursor ions (Figures 4a-d) at the elution times of the LC-MS/MS chromatographic peaks, and due to the presence of specific fragments for the nucleophile-modified Cys36, we could unequivocally demonstrate the sequence of the peptide and the presence of a mass increase of 138, 96 and 154 Da in Cys36 consistent with the formation of a Cys-nucleophile adduct at this site by DMD, CPD and DMBA respectively. The DMD-modified peptide fragmentation spectrum is dominated by an intense fragment corresponding to the loss of water from the precursor ion (Figure 4a); to confirm the DMD-adduct formation, a sub-fragmentation of this fragment at m/z = 532.5 was performed and the MS3 obtained was in agreement with the formation of the DMD-adduct on Cys36 (Figure 4b). Although the water-loss occurred in all replicas, this effect seemed to be probe- and peptide-specific as this behavior was not detected with BSA DMD-peptides identified in this study.

With these sets of experiments, the importance of the probes’ reactivity toward sulfenic acids is emphasized. On one hand, we have determined that some reactive probes, such as DMBA, allow complete labeling of protein-SOH (Figure 3f), but inhibit ESI-ionization (Figure 2b and Table 1). On the other hand, we observe that probes such as CPD show poor reactivity that does not enable stoichiometric labeling of Gpx3-SOH (Figure 3d), but advantageously does not affect ESI-ionization. In both cases, adduct presence did not interfere with peptides identification by automated search engines. This highlights the importance of developing specific probes with a good balance between reactivity, ionization, and MS/MS detection.

Due to the publication of a recent work describing linear β-ketoesters as probes for labeling of sulfenic acids[29], several labeling trials were performed with different linear carbon-nucleophiles (malononitrile, acetylacetone and methylacetoacetate, Supplemental Figure 14). By intact mass analysis, several major/minor peaks that do not correspond to the expected adduct were detected, and by LC-MS/MS, no peptide modified by these probes could be detected (data not shown).

High-throughput protein identification.- Br-DMD

Once the ability to identify DMD-adducts by mass spectrometry was demonstrated with a synthetic peptide, a single protein model, and with a sulfenic acid model, we next sought to determine whether or not DMD-adducts could be detected in a complex proteome such as cellular extract. To test this, we employed A431 epithelial cells, which naturally express high concentrations of EGFR and are used as a model for the study of epidermal growth factor receptor–mediated H2O2 production and oxidation of downstream proteins[22]. 80 μg of A431 protein extracts were separated on SDS-PAGE gel and the most intense area detected by Coomassie staining of the gel was cut and subjected to trypsin digestion prior to reduction with DTT and alkylation with Br-DMD. The resulting peptides were identified by high-throughput mass spectrometry. Among the 157 Cys-containing peptides identified from the 1804 unique identifications at a FDR = 1 %, 150 peptides were identified with a Cys-DMD adduct, which represent more than 95 % of all the Cys-containing peptides identified (Supplemental Dataset S1), demonstrating the utility and facile detection of DMD in massive proteomics experiments. As a proof of principle, DMD was used to label basal sulfenic acids in A431 cells. The proteome (80 μg) was separated by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was cut into 7 slices, each one trypsin-digested and analyzed separately on a linear ion trap. 19,469 scans were identified at a FDR = 1 %, corresponding to 8,569 unique peptides belonging to 2,181 unique proteins (Supplemental Dataset S2). From the unique peptides, 564 contain at least one Cys and 18 unique peptides were identified modified by DMD. Among the DMD-identified sites, the redox-sensitive cysteine of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)[15] was identified with a DMD-adduct. The tryptic peptide containing GAPDH Cys-149 contains a second Cys, but modified with NEM, pointing out the utility and selectivity of dimedone in targeting biologically relevant sulfenic acids. Finally, the use of DMD has been extended with success to the identification of basal sulfenylation in mouse livers in which more than 120 sulfenylated sites were identified and manually validated (manuscript in preparation).

Conclusions

Reversible oxidation of Cys is emerging as a regulatory mechanism of protein activity akin to phosphorylation. Formation of sulfenic acid acts as a molecular switch to modulate target proteins. From this perspective, it is crucial to develop mass spectrometry-based approximations in order to identify these target proteins and the exact Cys site of modification. Dimedone and other β-ketoesters have been described as sulfenic acid specific probes, but prior to this, no study has been performed to date regarding the effect of these probes on ionization efficiency or on fragmentation of labeled-peptides. Altogether, the data presented in this study provide strong evidence suggesting that DMD does not affect ESI-ionization efficiency. In particular, DMD showed more than 3-fold enhancement in ionization efficiency compared to IAM. Moreover, DMD forms a stable adduct enabling the identification of DMD-peptides by LC-MS/MS without any interferences with the database search algorithm. These results demonstrate that dimedone is a suitable probe for the high-throughput identification of sulfenic acid modifications in a whole proteome. The ability to detect protein sulfenic acid modifications by mass spectrometry in living cells provides a powerful tool and opens an avenue of possibilities to map redox-regulated pathways in healthy and/or disease states.

Experimental Procedures

Synthesis of YCVQQLK

The heptapeptide was synthesized on solid phase using standard Fmoc main chain and Boc/Trt side chain protection chemistry. Briefly, Fmoc of preloaded Wang resin (Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-Wang, 100-200 mesh size, 0.4 mmol/g loading, 375 mg, 0.15 mmol) was removed (20% piperidine /DMF, 30 min), and resin was washed with DCM (2 × 15 mL). Fmoc-Leu-OH (177 mg, 0.5 mmol, 3 equiv), HBTU (190 mg, 0.5 mmol, 3 equiv), HOBt (68 mg, 0.5 mmol, 3 equiv) and NMM (1.5 mL, 1.0 mmol, 6 equiv) in 15 mL of DMF were added to each batch of resin, shaken for 1 h, and the resin was washed with DCM (3 × 15 mL). Fmoc was removed with (20% piperidine / DMF, 30 min), and resin was washed again with DCM (3 × 15 mL). The procedure was repeated with Fmoc-Gln(Trt)-OH (twice), Fmoc-Val-OH, Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-OH and Fmoc-Trt(t-Bu)-OH to give the resin bound heptapeptide. Final product was cleaved from the resin, and Boc/Trt groups were removed by treatment with 15 mL of a 1% triethyl silane / 95% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) solution in DCM for 3 h followed by filtration. TFA was removed by passing a continuous flow of N2 through the solution. Products were purified by precipitation in chilled ether (−20 °C). Solids were concentrated by centrifugation (2500 rpm, 10 min), the solution was removed and solid was purified by preparative HPLC. After the final purification, the fractions containing heptapeptide were concentrated by lyophilization, resulting in off white powder. The pure heptapeptide was obtained as a mixture of disulfide and free thiol as observed in the LC-MS trace shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Gpx3 sulfenic acid model

Recombinant Cys64Ser Cys82Ser Gpx3 protein was expressed and purified as described previously[40]. The protein was reduced with 10 mM DTT (Research Products International Corp) during for 1h at 4°C prior to the removal of small molecules on Nap5 columns (GE Healthcare). 25 μM of Gpx3 was labeled with 10 mM of the different probes (DMD, CPD or DMBA) in presence of 1.5 Eq H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at room temperature with constant shaking. 5 μg of the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and separation was performed at 165 V for 35 min. The gel was Coomassie stained with Coomassie during 20 min and destained overnight. The gel band corresponding to the expected molecular size of Gpx3 was cut from the gel, treated with 10 mM DTT / 50 mM NEM (Acros Organics) and subjected to trypsin digestion as described previously[32].

BSA

5 μg of bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) were subjected to SDS-PAGE in five different lanes, and separation was performed at 165 V for 35 min. The gel was Coomassie stained during 20 min and destained overnight. The gel bands corresponding to the expected molecular size of BSA was cut, in-gel treated with 10 mM DTT followed by 50 mM alkylating agent (IAM, NEM, Br-DMD, Br-CPD or Br-DMBA) and subjected to trypsin digestion as above.

Cell culture, protein extraction and treatment

A431 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2, humidified atmosphere. Cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS (Invitrogen), 1% GlutaMax (Invitrogen), 1% MEM nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cells (3-4 × 106 cells/ml) were washed 3× with PBS and lysed in 50 mM triehanolamine, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40, 1× EDTA-free complete mini protease inhibitors (Roche), 200 U/ml catalase (Sigma). The cells lysates were cleared of cell debris by centrifugation for 10 min at 14,000 rpm. Protein concentrations of cell lysates were determined by standard BCA assay (Pierce). 80 μg of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE. The samples were treated with 10 mM DTT and 50 mM Br-DMD or 50 mM DMD for 2h at pH 7.0 prior tryptic digestion.

Top-Down Mass Spectrometry

DMD, CPD and DMBA labeled protein samples were submitted to intact mass analysis by liquid chromatography-MS (LC-MS) using a 1100 Series HPLC (Agilent Technologies) coupled to a linear ion trap mass spectrometer model LTQ-XL (ThermoScientific). Proteins were trapped, desalted and eluted operating at 200 μl/min with a gradient from 5 to 90 % B in 10 min (solvent A: 0.1% formic acid in H2O; solvent B: 0.1% formic acid in CH3CN). The LTQ was operated in a continuous full scan mode (300-2000 Th). The program Magic Transformer (MagTran), based on the algorithm designed by Zhang et al.[42], was used to deconvolute multiply charged ESI spectra.

Mass spectrometry

All samples were analyzed by liquid-chromatography-tandem MS (LCMS/MS) using an EASY-nLC II system coupled to a linear ion trap mass spectrometer model LTQ (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were concentrated and desalted on an RP precolumn (0.1 × 20 mm EASY-column, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and on-line eluted on an analytical RP column (0.075 × 100 mm EASY-column, Thermo Fisher Scientific), operating at 400 nl/min and using the following gradient: 5% B for 5 min, 5–15% B in 5 min, 15–55% B in 155 min, 30– 95% B in 7 min, and 95% B for 3 min [solvent A: 0.1% formic acid (v/v); solvent B: 0.1% formic acid (v/v), 80% CH3CN (v/v)]. For targeted experiments, the LTQ was programmed in the ‘selected MS/MS ion monitoring’ (SMIM) mode[31]. Briefly, an m/z 400-1,600 survey scan was firstly performed in order to check for the presence of digested peptides as well as peptide separation along the gradient. This survey scan is followed by a dependent MS/MS scan that fragments the most intense ions to make a general identification of the peptides present in the sample. For the heptapeptide experiments, subsequent MS/MS spectra were programmed on the doubly charged precursor ions of peptide YCVQQLK modified by IAM (at m/z 469.7), by NEM (at m/z 503.8), by DMD (at m/z 510.3), by CPD (at m/z 489.2) or by DMBA (at m/z 518.1). For the Gpx3 experiments, subsequent MS/MS spectra were programmed on the ions at m/z 541.3, at m/z 520.2 and at m/z 549.2, corresponding respectively to the doubly charged precursor ions of the DMD-modified, CPD-modified and DMBA-modified form of the Gpx3-peptide CGFTPQYK. One additional MS3 spectrum was programmed on ion at m/z 532.5, produced from the fragmentation of the DMD-modified peptide. The scan group was repeated twice per cycle. For massive peptide identification experiments, the LTQ was operated in a data-dependent MS/MS mode using the 10 most intense precursors detected in a survey scan from 400 to 1,600 m/z[43], or using mass ranges (400-600, 600-800, 800-1600 m/z) to improve coverage.

Peptide identifications

Protein identification was carried out using SEQUEST algorithm (Bioworks 3.2 package, Thermo Fisher Scientific), allowing optional modifications (Met oxidation, Cys modification depending on the reagent used), two missed cleavages, and mass tolerance of 2 and 1.2 amu for precursor and fragment ions, respectively. MS/MS raw files from the BSA and Gpx3 experiments were searched against a homemade database containing the sequence of proteins of interests, human keratins and porcine trypsin. MS/MS raw files from the mitochondrial models were searched against the Human Swissprot database containing porcine trypsin. The raw files were also searched against inverted databases constructed from the corresponding target databases. SEQUEST results were analyzed using the probability ratio method[38] and false discovery rates (FDR) of peptide identifications were calculated from the search results against the inverted databases using the refined method[44].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants GM102187 and CA174986. The authors also acknowledge funding the American Heart Association Scientist Development Award (0835419N to K.S.C.). The authors also wish to thank T.H. Truong for editorial assistance and G. West for helpful discussions.

References.

- 1.Winterbourn CC. Reconciling the chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:278. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antelmann H, Helmann JD. Thiol-based redox switches and gene regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1049. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumsta C, Thamsen M, Jakob U. Effects of oxidative stress on behavior, physiology, and the redox thiol proteome of Caenorhabditis elegans. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1023. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klomsiri C, Karplus PA, Poole LB. Cysteine-based redox switches in enzymes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1065. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Ruiz A, Lamas S. S-nitrosylation: a potential new paradigm in signal transduction. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62:43. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poole LB, Nelson KJ. Discovering mechanisms of signaling-mediated cysteine oxidation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:18. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:504. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato Y, Inaba K. Disulfide bond formation network in the three biological kingdoms, bacteria, fungi and mammals. FEBS J. 2012;279:2262. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddie KG, Carroll KS. Expanding the functional diversity of proteins through cysteine oxidation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:746. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paulsen CE, Carroll KS. Cysteine-mediated redox signaling: chemistry, biology, and tools for discovery. Chem Rev. 2013;113:4633. doi: 10.1021/cr300163e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulsen CE, Carroll KS. Orchestrating redox signaling networks through regulatory cysteine switches. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:47. doi: 10.1021/cb900258z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirooka Y, Sagara Y, Kishi T, Sunagawa K. Oxidative stress and central cardiovascular regulation. - Pathogenesis of hypertension and therapeutic aspects. Circ J. 0:74, 827. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0153. 201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei W, Liu Q, Tan Y, Liu L, Li X, Cai L. Oxidative stress, diabetes, and diabetic complications. Hemoglobin. 2009;33:370. doi: 10.3109/03630260903212175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visconti R, Grieco D. New insights on oxidative stress in cancer. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12:240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benitez LV, Allison WS. The inactivation of the acyl phosphatase activity catalyzed by the sulfenic acid form of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase by dimedone and olefins. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:6234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charles RL, Schroder E, May G, Free P, Gaffney PR, Wait R, Begum S, Heads RJ, Eaton P. Protein sulfenation as a redox sensor: proteomics studies using a novel biotinylated dimedone analogue. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1473. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700065-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poole LB, Klomsiri C, Knaggs SA, Furdui CM, Nelson KJ, Thomas MJ, Fetrow JS, Daniel LW, King SB. Fluorescent and affinity-based tools to detect cysteine sulfenic acid formation in proteins. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:2004. doi: 10.1021/bc700257a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giron P, Dayon L, Sanchez JC. Cysteine tagging for MS-based proteomics. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2011;30:366. doi: 10.1002/mas.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leonard SE, Carroll KS. Chemical ‘omics’ approaches for understanding protein cysteine oxidation in biology. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:88. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turell L, Botti H, Carballal S, Ferrer-Sueta G, Souza JM, Duran R, Freeman BA, Radi R, Alvarez B. Reactivity of sulfenic acid in human serum albumin. Biochemistry. 2008;47:358. doi: 10.1021/bi701520y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wani R, Qian J, Yin L, Bechtold E, King SB, Poole LB, Paek E, Tsang AW, Furdui CM. Isoform-specific regulation of Akt by PDGF-induced reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011665108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paulsen CE, Truong TH, Garcia FJ, Homann A, Gupta V, Leonard SE, Carroll KS. Peroxide-dependent sulfenylation of the EGFR catalytic site enhances kinase activity. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:57. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun QA, Wang B, Miyagi M, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Oxygen-coupled Redox Regulation of the Skeletal Muscle Ryanodine Receptor/Ca2+ Release Channel (RyR1): SITES AND NATURE OF OXIDATIVE MODIFICATION. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:22961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.480228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sethuraman M, McComb ME, Huang H, Huang S, Heibeck T, Costello CE, Cohen RA. Isotope-coded affinity tag (ICAT) approach to redox proteomics: identification and quantitation of oxidant-sensitive cysteine thiols in complex protein mixtures. J Proteome Res. 2004;3:1228. doi: 10.1021/pr049887e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leichert LI, Gehrke F, Gudiseva HV, Blackwell T, Ilbert M, Walker AK, Strahler JR, Andrews PC, Jakob U. Quantifying changes in the thiol redox proteome upon oxidative stress in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707723105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forrester MT, Thompson JW, Foster MW, Nogueira L, Moseley MA, Stamler JS. Proteomic analysis of S-nitrosylation and denitrosylation by resin-assisted capture. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:557. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doulias PT, Greene JL, Greco TM, Tenopoulou M, Seeholzer SH, Dunbrack RL, Ischiropoulos H. Structural profiling of endogenous S-nitrosocysteine residues reveals unique features that accommodate diverse mechanisms for protein S-nitrosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008036107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez-Acedo P, Nunez E, Gomez FJ, Moreno M, Ramos E, Izquierdo-Alvarez A, Miro-Casas E, Mesa R, Rodriguez P, Martinez-Ruiz A, Dorado DG, Lamas S, Vazquez J. A novel strategy for global analysis of the dynamic thiol redox proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:800. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.016469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian J, Wani R, Klomsiri C, Poole LB, Tsang AW, Furdui CM. A simple and effective strategy for labeling cysteine sulfenic acid in proteins by utilization of beta-ketoesters as cleavable probes. Chem Commun (Camb) 2012;48:4091. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17868k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogers LK, Leinweber BL, Smith CV. Detection of reversible protein thiol modifications in tissues. Anal Biochem. 2006;358:171. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jorge I, Casas EM, Villar M, Ortega-Perez I, Lopez-Ferrer D, Martinez-Ruiz A, Carrera M, Marina A, Martinez P, Serrano H, Canas B, Were F, Gallardo JM, Lamas S, Redondo JM, Garcia-Dorado D, Vazquez J. High-sensitivity analysis of specific peptides in complex samples by selected MS/MS ion monitoring and linear ion trap mass spectrometry: application to biological studies. J Mass Spectrom. 2007;42:1391. doi: 10.1002/jms.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redondo-Horcajo M, Romero N, Martinez-Acedo P, Martinez-Ruiz A, Quijano C, Lourenco CF, Movilla N, Enriquez JA, Rodriguez-Pascual F, Rial E, Radi R, Vazquez J, Lamas S. Cyclosporine A-induced nitration of tyrosine 34 MnSOD in endothelial cells: role of mitochondrial superoxide. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:356. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chalker JM, Gunnoo SB, Boutureira O, Gerstberger SC, Fernandez-Gonzalez M, Bernardes GJL, Griffin L, Hailu H, Schofield CJ, Davis BG. Methods for converting cysteine to dehydroalanine on peptides and proteins. Chemical Science. 2011;2:1666. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilisz I, Aranyi A, Pataj Z, Peter A. Enantiomeric separation of nonproteinogenic amino acids by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1269:94. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilm MS, Mann M. Electrospray and Taylor-Cone Theory, Doles Beam of Macromolecules at Last. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 1994;136:167. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta V, Carroll KS. Sulfenic acid chemistry, detection and cellular lifetime. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seo YH, Carroll KS. Quantification of protein sulfenic acid modifications using isotope-coded dimedone and iododimedone. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:1342. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez-Bartolome S, Navarro P, Martin-Maroto F, Lopez-Ferrer D, Ramos-Fernandez A, Villar M, Garcia-Ruiz JP, Vazquez J. Properties of average score distributions of SEQUEST: the probability ratio method. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:1135. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700239-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zabet-Moghaddam M, Shaikh AL, Niwayama S. Peptide peak intensities enhanced by cysteine modifiers and MALDI TOF MS. J Mass Spectrom. 2012;47:1546. doi: 10.1002/jms.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paulsen CE, Carroll KS. Chemical dissection of an essential redox switch in yeast. Chem Biol. 2009;16:217. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Truong TH, Garcia FJ, Seo YH, Carroll KS. Isotope-coded chemical reporter and acid-cleavable affinity reagents for monitoring protein sulfenic acids. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:5015. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.04.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Z, Marshall AG. A universal algorithm for fast and automated charge state deconvolution of electrospray mass-to-charge ratio spectra. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1998;9:225. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(97)00284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopez-Ferrer D, Martinez-Bartolome S, Villar M, Campillos M, Martin-Maroto F, Vazquez J. Statistical model for large-scale peptide identification in databases from tandem mass spectra using SEQUEST. Anal Chem. 2004;76:6853. doi: 10.1021/ac049305c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Navarro P, Vazquez J. A refined method to calculate false discovery rates for peptide identification using decoy databases. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1792. doi: 10.1021/pr800362h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.