Abstract Abstract

Pulmonary artery dissection is a complication associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension. This complication is described as acute in onset and is frequently fatal without intervention. We describe a patient with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and chest pain found to have an unsuspected chronic pulmonary artery dissection on postmortem examination. Chronic pulmonary artery dissection should be considered in patients with chest pain and worsening dyspnea, as the frequency this condition may be underestimated.

Keywords: pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary artery dissection, complication, chest pain

Pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) is a progressive, life-threatening condition associated with symptoms that become more prevalent with disease progression.1,2 In patients with PAH, the cause of chest pain is unclear but is commonly attributed to myocardial ischemia.3-6 However, acute pulmonary artery dissection is also associated with new-onset chest pain, often with fatal outcomes.7,8 We describe a patient who had progressively worsening idiopathic PAH and chest pain, which resolved after initiation of intravenous prostaglandin analog therapy, and was found to have had acute and chronic pulmonary artery dissections on postmortem examination.

Case description

A 56-year-old female with idiopathic PAH diagnosed 11 years earlier and treated with nifedipine, bosentan (Tracleer, Actelion, San Francisco), sildenafil (Revatio, Pfizer, New York), inhaled iloprost (Iloprost, Actelion, San Francisco), and warfarin presented with 2 weeks of severe, intermittent chest pain. Chest pain was sharp and nonradiating, located over the left anterior chest, lasting 20–60 minutes, and aggravated with exertion or deep inspiration. This pain was unrelieved by antacids and partially relieved by oxygen and rest. Physical examination revealed a pulse rate of 100/minute, blood pressure of 130/70 mmHg, and pulse oximetry of 96% (with oxygen administered at 2 L/min). Chest auscultation revealed clear lung fields, a 3/6 systolic murmur, and no pericardial rub. No chest wall tenderness was elicited. Ascites was absent, and lower-extremity edema was present. Initial and subsequent electrocardiographs during episodes of chest pain revealed tachycardia without ischemic changes. Concomitant serum troponin levels were normal. A single-photon emission computed tomography (CT) myocardial perfusion test with adenosine did not demonstrate perfusion defects. Echocardiography showed right ventricle enlargement, right ventricular systolic pressure of 60 mmHg, and a small pericardial effusion. Chest CT demonstrated no vascular filling defects, and the pulmonary artery diameter (6.8 cm) was greater than that from a chest CT obtained 1 year earlier (5.7 cm). Right heart catheterization was performed and, relative to earlier studies, demonstrated a declining hemodynamic profile (Table 1). The patient agreed to parenteral prostacyclin therapy, and intravenous treprostinil (Remodulin, United Therapeutics, Silver Spring, MD) was initiated. As the treprostinil infusion was increased, she experienced significant improvements in exercise tolerance and resolution of chest pain. Four months after treprostinil initiation, while receiving 35 ng/kg/min, her 6-minute walk distance improved by 200 feet, to 1,150 feet. Right heart catheterization demonstrated an improved hemodynamic profile (Table 1). Weeks later, while attending a family function, she and her spouse developed fever, cough, and myalgias after contact with a sick child. The spouse’s symptoms resolved, but she was hospitalized for dyspnea. Chest CT revealed parenchymal infiltrates, pericardial effusion, and no pulmonary artery dissection. Echocardiography revealed a moderate-sized pericardial effusion with right ventricular collapse. Forty-eight hours later, atrial fibrillation developed, and respiratory failure progressed, requiring mechanical ventilation and vasopressors. Drainage of 800 mL of sterile, serous, pericardial fluid provided hemodynamic improvement. However, respiratory failure persisted, and after 7 days, her family requested withdrawal of care. Permission to perform an autopsy was granted.

Table 1.

Right heart catheter measurements

| Time | Therapy | Dose | RAP, mmHg | PAP, mmHg (mean) | PAOP, mmHg | CO, L/min | PVR, mmHg/L/min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb 1996 | None | … | 15 | 100/50 (67) | 13 | 2.8 | 19.2 |

| Nitric oxide | 10 ppm | 16 | 80/35 (50) | 12 | 3.8 | 10 | |

| Feb 1998 | Nifedipine, warfarin |

60 mg/day, 5 mg/day |

15 | 82/35 (51) | 12 | 4.0 | 9.8 |

| Apr 2003 | Bosentan, nifedipine, warfarin |

125 mg bid, 60 mg/day, 5 mg/day |

10 | 109/45 (66) | 11 | 2.8 | 19.6 |

| Dec 2005 | Bosentan, sildenafil, nifedipine, warfarin |

125 mg bid, 25 mg tid, 60 mg/day, 5 mg/day |

11 | 110/50 (70) | 10 | 3.0 | 20 |

| Jun 2007 | Bosentan, sildenafil, iloprost, nifedipine, warfarin |

125 mg bid, 40 mg tid, 2.5 μg 6 times/day, 60 mg/day, 5 mg/day |

7 | 115/50 (72) | 13 | 2.9 | 20.3 |

| Oct 2007 | Treprostinil, bosentan, sildenafil, warfarin |

35 ng/kg/min, 125 mg bid, 40 mg tid, 5 mg/day |

8 | 90/50 (63) | 12 | 4.9 | 10.4 |

Measurements were obtained after administration of the therapy. RAP: right atrial pressure, PAP: pulmonary artery pressure, PAOP: pulmonary artery opening pressure, CO: cardiac output, PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance, bid: 2 times/day, tid: 3 times/day.

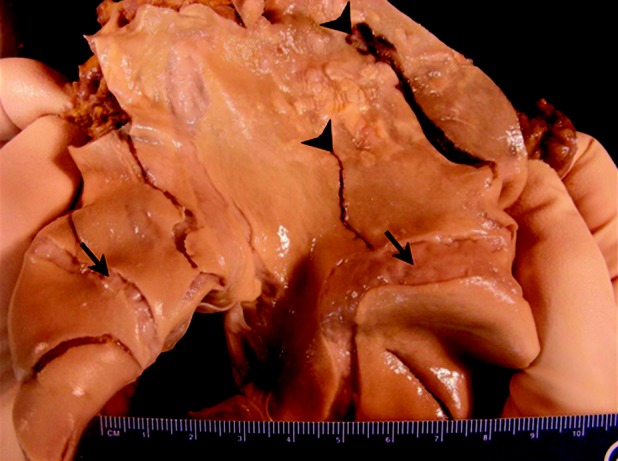

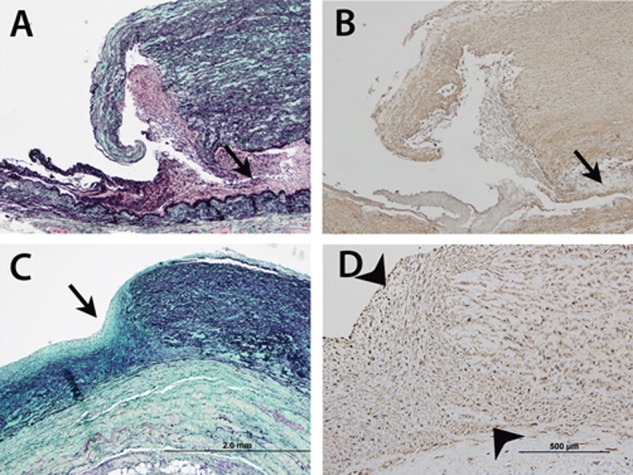

Postmortem examination demonstrated right ventricular hypertrophy with patent coronary arteries, no evidence of recent or healed myocardial infarction, and normal pericardium. Bilateral parenchymal consolidation was noted, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa was isolated from the lung. No pulmonary emboli were identified. The pulmonary trunk measured 15 cm in greatest circumference. Within the main pulmonary artery, 8 intimal tears were observed, with the largest measuring 9 cm in length (Fig. 1). Microscopic examination of the pulmonary artery revealed an acute intimal tear and several well-healed tears, with organized collagen and vascular smooth muscle cell remodeling (Fig. 2). Pulmonary arterioles revealed intimal proliferation, medial thickening, concentric laminar fibrosis, and plexiform lesions. No organisms were identified on smear or culture from the pericardial fluid.

Figure 1.

The main pulmonary arterial trunk opened to display massive aneurysmal dilatation of the pulmonary artery and multiple pulmonary artery tears (pulmonic valve is at lower left). The largest disruption (arrowhead, right) begins adjacent to the pulmonic valve and is 9 cm in length and 1.3 cm in greatest width. Note the interconnected nature of healed tears (arrows) and acute tears (arrowheads). Atherosclerotic plaques are also evident, indicative of long-standing pulmonary hypertension.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of main pulmonary arterial wall, which is greatly thickened. A, Near-transmural acute tear shows adherent blood and thrombotic material and dissection located at the outer third of media (arrow). B, Immunostain with anti–smooth muscle actin antibody confirms location of dissection. C, Remodeled tear of main pulmonary artery (arrow) shows ingrowth of cells, and collagen (staining blue-green) and elastin (staining black) production. D, Immunostain with anti–smooth muscle actin antibody at higher magnification, of chronic tear site (arrowheads) confirms that remodeling cells are vascular smooth muscle cells. A and C are Movat pentachrome stained; A–C are at same magnification (scale bar in C: 2.0 mm); D is a higher-power view (scale bar: 500 μm).

Discussion

At time of diagnosis, chest pain occurs in 22%–47% of patients with PAH.1,2 Chest pain is often ascribed to right ventricular ischemia associated with normal coronary anatomy or left main coronary artery compression.3-6 However, pulmonary vascular conditions such as pulmonary artery dissection or pulmonary embolism are also associated with chest pain. Symptoms associated with pulmonary artery dissection include chest pain, fatigue, and progressive dyspnea. Notably, several reports describe acute onset of chest pain followed by cardiovascular collapse and death.7-9 Pathologic inspection of the pulmonary artery frequently reveals dilatation with an acute transmural tear and dissection into the mediastinum or pericardium.9,10 However, clinical and pathological description of chronic pulmonary artery dissection has not been well described. Clinical reports have described symptomatic pulmonary artery enlargement of weeks and months duration with poor outcomes but without pathologic description of the pulmonary vasculature.11,12 A report by Butto and colleagues10 of pulmonary artery aneurysms describes features similar to our case: well-demarcated intimal lesions that under microscopy revealed neointima formation and healing of a previous dissection. This report indicates that pulmonary artery dilatation can lead to intimal injury, followed by healing noted by organizing collagen and vascular smooth muscle cells along the healed dissection site. In the case of this patient, we suspect that chest pain was related to right ventricular ischemia and chronic pulmonary artery dissection that resolved with initiation of treprostinil. Moreover, the findings of recent and healed intimal tears of the pulmonary artery indicate that large-vessel remodeling in the form of organized collagen and neointimal formation had occurred weeks to months before her death. Although fatal, acute pulmonary artery dissection has been previously reported, subclinical disease may also exist, manifested as recurrent or intermittent chest pain, as noted in the present case. With increasing survival for patients with PAH, complications such as pulmonary artery dissection may become more common. Moreover, since postmortem examination is frequently not performed, the frequency of chronic pulmonary artery dissection may be underestimated.

Source of support: Nil.

Conflict of interest: AGD is on the speaker’s bureau for Gilead, Actelion, and United Therapeutics and has received honoraria from Gilead, Actelion, and United Therapeutics for speaking. He does not own stock in any of the above companies. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Rich S, Dantzker DR, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, Detre KM, Fishman AP, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension: a national prospective study. Ann Intern Med 1987;107:216–223. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Brown LM, Chen H, Halpern S, Taichman D, McGoon MD, Farber HW, Frost AE, et al. Delay in recognition of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2011;140:19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Gómez A, Bialostozky D, Zajarias A, Santos E, Palomar A, Martínez ML, Sandoval J. Right ventricular ischemia in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:1137–1142. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.van Wolferen SA, Marcus JT, Westerhof N, Spreeuwenberg MD, Marques KM, Bronzwaer JG, Henkens IR, et al. Right coronary artery flow impairment in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2008;29:120–127. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Mesquita SM, Castro CR, Ikari NM, Oliveira SA, Lopes AA. Likelihood of left main coronary artery compression based on pulmonary trunk diameter in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Med 2004;116:369–374. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.de Jesus Perez VA, Haddad F, Vagelos RH, Fearon W, Feinstein J, Zamanian RT. Angina associated with left main coronary artery compression in pulmonary hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant 2009;28:527–530. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Khattar RS, Fox DJ, Alty JE, Arora A. Pulmonary artery dissection: an emerging cardiovascular complication in surviving patients with chronic pulmonary hypertension. Heart 2005;91:142–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Degano B, Prevot G, Tetu L, Sitbon O, Simmoneau G, Humbert M. Fatal dissection of the pulmonary artery in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2009;18:181–185. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Graham JK, Shehata B. Sudden death due to dissecting pulmonary artery aneurysm. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2007;28:342–344. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Butto F, Lucas RV, Edwards JE. Pulmonary artery aneurysm: a pathologic study of five cases. Chest 1987;91:237–241. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Steurer J, Jenni R, Medici C, Vollrath T, Hess OM, Siegenthaler W. Dissecting aneurysm of the pulmonary artery with pulmonary hypertension. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;142:1219–1221. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Smalcelj A, Brida V, Samarzija M, Matana A, Margetic E, Drinkovic N. Giant, dissecting, high pressure pulmonary artery aneurysm. Tex Heart Inst J 2005;32:589–594. [PMC free article] [PubMed]