Abstract

Directed differentiation protocols enable derivation of cardiomyocytes from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSC) and permit engineering of human myocardium in vitro. However, hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes are reflective of very early human development, limiting their utility in the generation of in vitro models of mature myocardium. Here, we developed a new platform that combines three-dimensional cell cultivation in a microfabricated system with electrical stimulation to mature hPSC-derived cardiac tissues. We utilized quantitative structural, molecular and electrophysiological analyses to elucidate the responses of immature human myocardium to electrical stimulation and pacing. We demonstrated that the engineered platform allowed for the generation of 3-dimensional, aligned cardiac tissues (biowires) with frequent striations. Biowires submitted to electrical stimulation markedly increased myofibril ultrastructural organization, displayed elevated conduction velocity and altered both the electrophysiological and Ca2+ handling properties versus non-stimulated controls. These changes were in agreement with cardiomyocyte maturation and were dependent on the stimulation rate.

INTRODUCTION

Since adult human cardiomyocytes are essentially post-mitotic, the ability to differentiate cardiomyocytes from human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells (hESC and hiPSC, respectively)1–4 represents an exceptional opportunity to create in vitro models of healthy and diseased human cardiac tissues that can also be patient specific5 and useful in screening new therapeutic agents efficacy. However, differentiated cells display a low degree of maturation6 and are significantly different from adult cardiomyocytes.

hESC-derived cardiomyocytes display immature sarcomere structure characterized by the absence of H zones, I bands and M lines (embryoid bodies (EBs) day 40 (ref.7)), high proliferation rates (~17%, EBs day 37 (ref.8), ~10%, EBs day 21–35 (ref.7)), immature action potentials9 and Ca2+ handling properties9–13 with contraction shown to be, in many cases, dependent on trans-sarcolemmal Ca2+ influx and not on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release10. hESC-based engineered cardiac tissues also display immature characteristics, including immature sarcomere structure14, high proliferation rates (15–45%14, 10–30%15) and expression of the fetal gene program16–18. This is an important caveat when utilizing these cells as models of adult human tissue6.

During embryonic development, cardiac cells are exposed to environmental cues such as extracellular matrix (ECM), soluble factors, mechanical signals, and electrical fields that may determine the emergence of spatial patterns and aid in tissue morphogenesis19,20. Exogenously applied electrical stimulation has also been shown to influence cell behavior21–23.

We have created a new platform that combines architectural and electrical cues to generate a microenvironment conducive to maturation of three-dimensional (3D) hESC- and hiPSC-derived cardiac tissues, termed biowires. Cells were seeded in collagen gel around a template suture in a microfabricated well and subjected to electrical field stimulation of progressive frequency increase. Consistent with maturation, stimulated biowires exhibited cardiomyocytes with a remarkable degree of ultrastructural organization, improved conduction velocity and enhanced Ca2+ handling and electrophysiological properties.

RESULTS

Engineering of human cardiac biowires

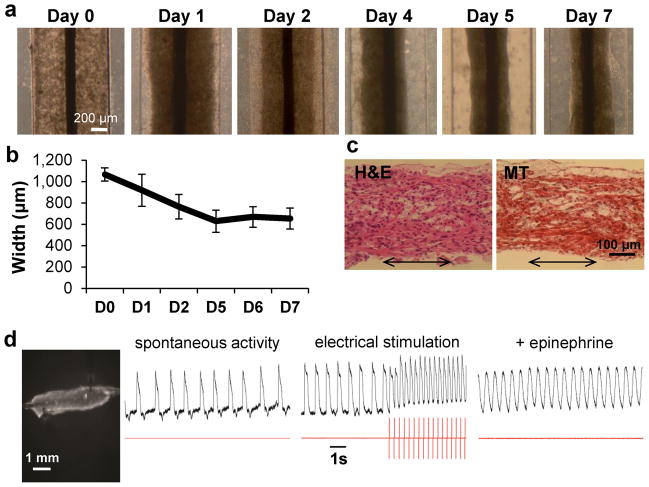

hPSC-cardiomyocytes and supporting cells obtained from directed differentiation protocols were used to generate 3D, self-assembled cardiac biowires by cell seeding into a template polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) channel, around a sterile surgical suture in type I collagen gels (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1a). Seeded cells remodeled and contracted the collagen gel matrix during the first week (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a) with ~40% gel compaction (Fig. 1b, final width ~600 μm). This allowed biowire removal from PDMS template (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b).

Figure 1.

Generation of human cardiac biowires. (a) Pre-culture of hESC-cardiomyocyte in biowire template for 7 days allowed cells to remodel the gel and contract around the suture. (b) Quantification of gel contraction demonstrated compaction of ~40% (average ± s.d., n = 3–4 wires). (c) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Masson’s Trichrome (MT) staining of biowire sections show cell alignment along the suture axis (arrows represent suture axis). (d) Optical mapping of impulse propagation. A representative picture (left) of a biowire being imaged with potentiometric fluorophore (DI-4-ANEPPS) showing the spontaneous electrical activity, with impulse propagation recording (left trace recording), response to electrical stimulation (middle trace recording, stimulation frequency is depicted in red trace below; electrical capture can be seen during stimulation along with associated change in morphology of action potential and positive baseline shift) and increase in frequency of spontaneous response under pharmacological stimulation (epinephrine, right trace recording). (e, f) Electrical stimulation regimens applied. Pre-cultured biowires were submitted to electrical stimulation at 3–4 V/cm for 1 week. (e) Electrical stimulation started at 1 Hz and was progressively increased to 3 Hz where it was kept for the remainder of the week (low frequency ramp-up stimulation regimen or 3 Hz). (f) Stimulation rate was progressively increased from 1 to 6 Hz (High frequency ramp-up stimulation regimen or 6 Hz). (g) At the end of the stimulation, biowires were assessed for functional, ultrastructural, cellular and molecular responses as depicted. (a–d) Illustrate results with Hes2 hESC-derived cardiomyocytes.

Histology revealed cell alignment along the axis of the suture (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1c). Biowires beat synchronously and spontaneously between 2 and 3 days post-seeding and kept beating after gel compaction, demonstrating that the setup enabled electromechanical cell coupling (Supplementary Video 1). Biowires could be electrically paced and responded to physiological agonists such as epinephrine (β-adrenergic stimulation) by increasing spontaneous beating frequency (Fig. 1d).

After pre-culture for 1 week, biowires were either submitted to electrical field stimulation or cultured without stimulation (non-stimulated controls) for 7 days. We utilized two different protocols where stimulation rate was progressively and daily increased from 1 to 3 Hz (Fig. 1e, Low frequency ramp-up regimen, referred to as low frequency or 3 Hz from here on) or from 1 to 6 Hz (Fig. 1f, High frequency ramp-up regimen, referred to as high frequency or 6 Hz from here on) to assess whether effects were dependent on stimulation rate.

Physiological hypertrophy in stimulated biowires

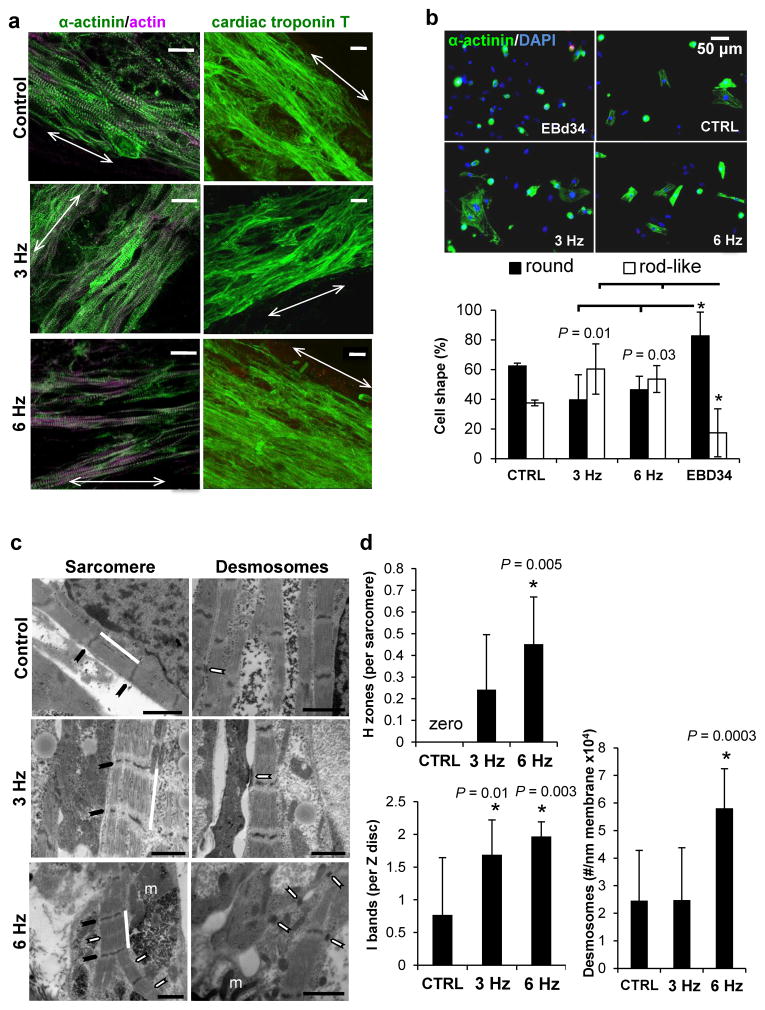

After 2 weeks in culture, immunostaining demonstrated that cells throughout the biowires strongly expressed cardiac contractile proteins sarcomeric α-actinin, actin and cardiac Troponin T (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2 and 3). Sarcomeric banding of the contractile apparatus (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 1d, 2a and 3) and myofibrillar alignment along the suture axis was qualitatively similar to the structure of adult heart22. Biowires kept in culture for 3 and 4 weeks maintained cell alignment and their contractile apparatus structure as evidenced by confocal and transmission electron microscopy (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Culture in biowire in combination with electrical stimulation promoted physiological cell hypertrophy and improved cardiomyocyte phenotype. (a) Representative confocal images of non-stimulated (control) and electrically stimulated biowires (3 and 6 Hz ramp-up) showing cardiomyocyte alignment and frequent Z disks (arrows represent suture axis). Scale bar 20 μm. (b) Analysis of cardiomyocyte cell shape in different conditions reveals that biowires cultivated under electrical stimulation displayed significantly less round cells and more rod-like cells (average ± s.d., EBd34 vs. 3 Hz P = 0.01 for both rod and round like; EBd34 vs. 6 Hz P = 0.03 for both round and rod-like). (c) Ultrastructural analysis shows that electrical stimulation at 6 Hz induces cardiomyocyte self-organization. Representative images of non-stimulated (control) and electrically stimulated biowires showing sarcomere structure (Sarcomere panel, white bar; Z disks, black arrow; H zones, white arrows; m, mitochondria) and presence of desmosomes (Desmosomes panel, white arrows). Scale bar 1 μm. (d) Morphometric analysis (average ± s.d.) showing ratio of H zones to sarcomeres (CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.005) ratio of I bands to Z disks (CTRL vs. 3 Hz, P = 0.01; CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.003) and number of desmosomes per membrane length (CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.0003). *denotes statistically significant difference between group and control. In normal adult cells the ratio of H zones to sarcomeres is 1 and of I bands to Z disks is 2. (a–d) Illustrate results with Hes2 hESC-derived cardiomyocytes. n = 3–4 per condition.

Early in cardiac development, cardiomyocytes are round shaped cells differentiating into rod-shaped phenotype after birth24. Adult human cardiomyocytes display a structurally rigid architecture, retaining a rod-like shape25 immediately after dissociation while hESC-cardiomyocytes remain round. We dissociated age matched EBs (EBd34) and biowires and seeded the cells into Matrigel-coated plates (Fig. 1g). While ~80% of cardiomyocytes from EBd34 displayed a round phenotype, this number was significantly lower (~50% less) in electrically stimulated samples (Fig. 2b). Percentage of rod-like cardiomyocytes was significantly higher (~4 fold) in electrically stimulated biowires (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 5) as compared to EBd34.

During development, cardiomyocytes undergo physiological hypertrophy characterized by increased cell size followed by changes in sarcomere structure and downregulation of fetal genes26. There was a significant increase in cardiomyocyte size (area of plated cells) in biowire conditions compared to cardiomyocytes from age matched EBs (EBd34) (Supplementary Table 1, EBd34 vs. CTRL P = 0.034; EBd34 vs. 3 Hz P = 0.003; EBd34 vs. 6 Hz regimen P = 0.01). Atrial natriuretic peptide (NPPA), brain natriuretic peptide (NPPB) and α-myosin heavy chain (MYH6) are molecules highly expressed in fetal cardiomyocytes and upregulated during pathological hypertrophy in diseased adult ventricular cardiomyocytes. Downregulation of the fetal cardiac gene program (NPPA, NPPB, MYH6) in hESC-derived cardiomyocyte biowires (Supplementary Fig. 6), compared to age matched EBs, in concert with cell size increase, suggested physiological hypertrophy and a more mature phenotype. Potassium inwardly-rectifying channel gene (KCNJ2), that plays important roles in cell excitability and K+ homeostasis27, was upregulated compared to EBd34 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

hESC-cardiomyocytes cultured in biowires also displayed lower proliferation rates than those in EBs (Supplementary Fig. 7, EBd20 vs. EBd34, P = 0.002; EBd34 vs. CTRL, P = 0.019; EBd34 vs. 3 Hz, P = 0.016; EBd34 vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.015) and the percentage of cardiomyocytes in each condition remained unchanged after culture for 2 weeks (48.2 ± 10.7%, Supplementary Fig. 8). Initial percentages of CD31 (2.4 ± 1.5%, endothelial cells28), CD90 (34.4 ± 23%, fibroblasts28), calponin (35 ± 22%, smooth muscle cells) or vimentin (80 ± 22%, non-myocytes) positive cells in EBd20 population, were largely maintained after biowire culture, suggesting that the observed improvements were not related to the induction of a particular cell type.

Maturation of contractile apparatus

Cells in non-stimulated biowires displayed well-defined Z discs and myofibrils (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Fig. 2c and 3) but no signs of Z disc alignment. In contrast, biowires stimulated under the high frequency regimen showed signs of maturation, such as organized sarcomeric banding with frequent myofibrils that converged and displayed aligned Z discs (Fig. 2c, 6 Hz, Supplementary Fig. 2c and 3), numerous mitochondria (Fig. 2c, 6 Hz; Supplementary Fig. 2c and 3) and desmosomes (Fig. 2c). In the 6 Hz condition, mitochondria were positioned closer to the contractile apparatus than in control or 3 Hz conditions (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 2c and 3b).

Electrically stimulated samples displayed a sarcomeric organization more compatible with mature cells than non-stimulated controls as shown by a significantly higher presence of H-zones per sarcomere (Fig. 2d, CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.005; Supplementary Fig. 2d, CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.001) and I-bands per Z disc (Fig. 2d, CTRL vs. 3 Hz, P = 0.01; CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.003; Supplementary Fig. 2d, CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.0004). Biowires stimulated at 6 Hz regimen also displayed a significantly higher number of desmosomes per membrane length than both non-stimulated controls and 3 Hz-stimulated biowires (Fig. 2d, P = 0.0003). In hiPSC-derived cardiomyocyte biowires, areas with nascent intercalated discs were frequently seen (Supplementary Fig. 2c and 3b).

Functional assessment of engineered biowires

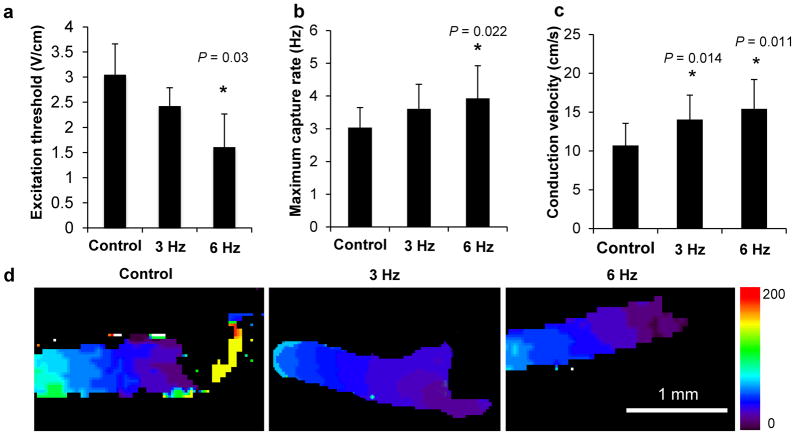

Electrical stimulation with the 6 Hz regimen significantly improved biowire’s electrical properties, leading to a statistically significant reduction in the excitation threshold (Fig. 3a, CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.03) and an increase in the maximum capture rate (Fig. 3b, CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.022, Supplementary Fig. 2 and 3) as analyzed by point stimulation at the end of cultivation in conjunction with optical mapping of impulse propagation (Supplementary Fig. 9a, Supplementary Videos 2–5). Optical mapping demonstrated higher MCR with field stimulation (5.2 Hz) than with point stimulation (4 Hz) (Supplementary Fig. 9b, 5.2 Hz capture with intermittent capture at 6 Hz, Supplementary Videos 6–9). During field stimulation all cells received the stimulus at the same time and response was not limited by each cell’s propagation limitations. Conduction velocity (CV), assessed upon point stimulation at the end of cultivation was ~40 and ~50% higher in the samples electrically stimulated during culture (3 Hz and 6 Hz, respectively), than non-stimulated controls (Fig. 3c,d, CTRL vs. 3 Hz, P = 0.014; CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.011). Improvements in electrical properties (ET, MCR and CV) were more pronounced with the high frequency regimen compared to the low frequency one. Improvement in conduction velocity was found to be in direct correlation with the average number of desmosomes (Supplementary Fig. 10, R2 = 0.8526), a molecular complex of cell-cell adhesion proteins.

Figure 3.

Functional assessment of engineered biowires demonstrated that electrical stimulation significantly improved electrical properties. Electrical stimulation improves (a) excitation threshold (CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.03, as measured by field stimulation and videomicroscopy), (b) maximum capture rate (CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.022, as measured by point stimulation and optical mapping) and (c) electrical impulse propagation rates (CTRL vs. 3 Hz, P = 0.014; CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.011, as measured by point stimulation and optical mapping). (d) Representative images of conduction velocity activation maps in biowires. *denotes statistically significant difference between group and control. Heat map = 0 to 200 ms. Average ± s.d., n = 6–10 per condition. (a–d) Illustrate results with hESC-derived cardiomyocytes obtained from Hes2 cell line.

Stimulation improves Ca2+ handling properties

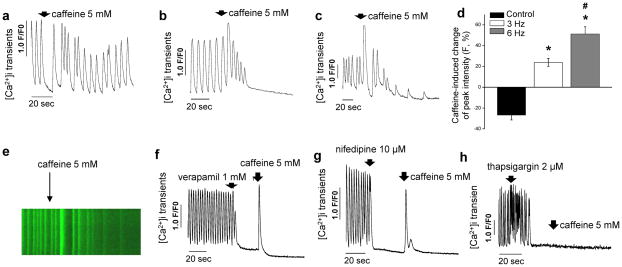

Either all10 or the majority12 of hESC-cardiomyocytes rely on sarcolemmal Ca2+ influx rather than on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release for contraction, differing markedly from adult myocardium. We tested the effect of caffeine, an opener of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ryanodine channels, on cytosolic Ca2+ in single cells isolated from biowires (Fig. 1g). In accordance with previous work10, none of the hESC-cardiomyocytes in non-stimulated controls were responsive to caffeine (Fig. 4a), while electrically stimulated cells in both 3 and 6 Hz conditions responded to caffeine by inducing an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 4b,c). Quantification of Ca2+ transient amplitudes showed that electrically stimulated cells displayed significantly higher amplitude intensity in response to caffeine than non-stimulated controls, in a stimulation frequency dependent manner (Fig. 4d,e). Blockage of L-type Ca2+ channels in cells from 6 Hz biowires with either verapamil (Fig. 4f) or nifedipine (Fig. 4g) led, as expected in mature cells, to cessation in Ca2+ transients. Addition of caffeine post blockage of L-type Ca2+ channels led to Ca2+ release into the cytosol (Fig. 4f,g). Blockage of the ion transport activity of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) by addition of thapsigargin (Fig. 4h) lead to the cessation of calcium transients with time due to the depletion of Ca2+ from sarcoplasmic reticulum. Cardiomyocytes from 6 Hz condition also demonstrated a faster rising slope and time to peak, parameters that represent the kinetics of Ca2+ release into the cytosol, and faster τ-decay and time to base, parameters that represent the kinetics of clearance of Ca2+ from the cytosol (Supplementary Table 2). Taken together, these data indicated that cardiac biowires that underwent the 6 Hz stimulation regimen during culture displayed Ca2+ handling properties compatible with functional sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Figure 4.

Electrical stimulation promoted improvement in Ca2+ handling properties. (a) Non-stimulated control cells did not respond to caffeine while cells from (b) 3 Hz ramp-up and (c) 6 Hz ramp-up protocols respond to caffeine by releasing more Ca2+ into the cytoplasm and depleting sarcoplasmic reticulum. (d) Caffeine-induced change of peak fluorescent intensity among different experimental groups (mean ± s.e.m. after normalizing the peak fluorescence intensity before administration of caffeine) (CTRL vs. 3 Hz, P = 1.1x10−6; CTRL vs. 6 Hz, P = 2.1 x10−7; 3 Hz vs. 6 Hz, P = 0.003; n = 8–10 per condition). (e) Representative fluorescence recording of Ca2+ transients before and after administration of caffeine at 5 mM (arrow) in 6 Hz stimulated cells. Inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channels with (f) verapamil or (g) nifedipine and blockage of SERCA channels with (h) thapsigargin in 6 Hz cells before addition of caffeine shows that cardiomyocytes stimulated with the 6 Hz regimen display Ca2+ handling properties compatible with functional sarcoplasmic reticulum. *denotes statistically significant difference between group and control. #denotes statistically significant difference between 3 Hz and 6 Hz group. (a–h) Illustrate results with hESC-derived cardiomyocytes obtained from Hes2 cell line and represent measurements performed in single cell cardiomyocytes after dissociation from biowires.

Stimulation alters electrophysiological properties

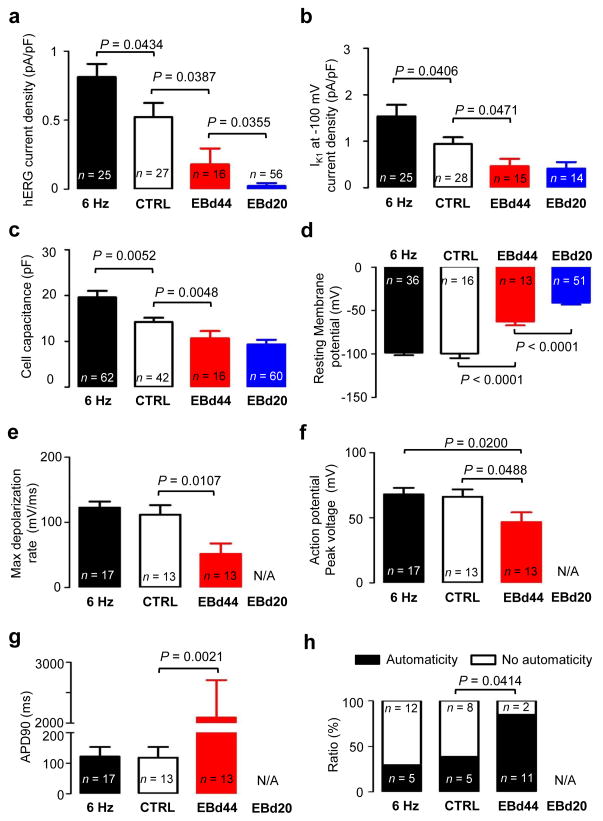

To assess maturity, we measured action potentials, hERG and IK1 currents11 in cardiomyocytes derived from biowires and EBs (Fig. 5). hERG currents were larger (P = 0.0434) in 6 Hz-stimulated biowires (0.81 ± 0.09 pA/pF) than non-stimulated controls (0.52 ± 0.10 pA/pF) (Fig. 5a) without differences in their biophysical properties (Supplementary Fig. 11). Cardiomyocytes from both biowire groups had higher hERG levels compared to those from EBs day 20 or 44 (Fig. 5a). Similarly, IK1 densities were higher (P = 0.0406) in 6 Hz-biowires (1.53 ± 0.25 pA/pF, 6 Hz) than in controls (0.94 ± 0.14 pA/pF, CTRL) and IK1 levels in both biowire groups were higher (P = 0.0005) than those recorded in EB-derived cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5b). Cell capacitance, a measure of cell size, showed higher (P = 0.0052) values in the 6 Hz-biowires (19.59 ± 1.41 pF; 6 Hz) compared to control biowires (14.23 ± 0.90 pF; CTRL) and smaller (P = 0.0041) capacitance in EB-derived cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5c). Resting membrane potentials (Vrest) of the cardiomyocytes from biowires were more negative (P < 0.0001) than in EB-cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5d). Interestingly, after correcting for the liquid junction potential which was ~16 mV, the values of Vrest recorded in biowire cardiomyocytes with the patch-clamp method were well below the equilibrium potential for Nernst potential for K+ (EK = −96 mV) suggesting that hyperpolarizing currents, possibly those generated by the Na+ pump29,30, strongly influenced Vrest. Consistently, we found that the cardiomyocytes from biowires had a very low resting membrane conductance, which correlated (R = 0.5584, P < 0.0001) with Vrest, while IK1 currents exhibited negative correlations with Vrest (R = 0.2267, P = 0.0216, Supplementary Fig. 12). Maximum depolarization rates (Fig. 5e) and peak voltages of the action potentials (Fig. 5f) did not differ between the two biowire groups. However, both properties were improved compared to EBs (P = 0.5248 and P = 0.0488, respectively). Action potential durations were longer (P = 0.0021) with greater variation in EB-derived cardiomyocytes than biowire-derived cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5g, Supplementary Fig. 13), suggesting less electrophysiological diversity and more maturation in biowires. Automaticity was greater (P = 0.0414) in EB-derived cardiomyocytes compared to control biowires (Fig. 5h), which was comparable to 6 Hz-stimulated biowires. Taken together, these results support the conclusion that biowires and electrical stimulation at the 6 Hz regimen promoted electrophysiological maturation.

Figure 5.

Electrophysiological properties in single cell cardiomyocytes isolated from biowires or embryoid bodies and recorded with patch-clamp. Six Hz stimulated biowire (black), control biowire (white), EBd44 (red) and EBd20 (blue) are shown. (a) hERG tail current density, (b) IK1 current density measured at −100 mV, (c) cell capacitance, (d) resting membrane potential, (e) maximum depolarization rate of action potential, (f) action potential peak voltage, (g) action potential duration measured at 90% repolarization and (h) ratio of cells displaying spontaneous beating (automaticity) or no spontaneous beating (no automaticity). (a–h) Illustrate results with hESC-derived cardiomyocytes obtained from Hes2 cell line. Average ± s.e.m.

DISCUSSION

Although electrical field stimulation was used previously with cells from primary sources and animal tissues22,23, we showed here for the first time that the combination of geometric control of 3D tissue assembly and electrical stimulation of hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and supporting cells improved electrical and ultrastructural properties of human cardiac tissue, resulting in cell maturation. The biowire suture remained anchored to the device platform during matrix remodeling, generating tension that resulted in cell alignment along the suture axis.

Normal human fetal heart rate varies significantly, being maintained at ~3 Hz for most of the time31 while the adult resting heart rate is ~1 Hz31. The rate change is associated with changes in contractile protein expression and suggests a possible dependence of cardiac maturation on stimulation rate. The fact that the progressive increase from 1 to 6 Hz was the best condition tested, was surprising since 3 Hz is the average fetal heart rate31. This could be a compensatory mechanism for the lack of other important cells types and cell-cell developmental guidance in the in vitro setting. Since field stimulation frequency was gradually increased over 7 days in culture, the 6 Hz group might only lose capture (exceed the rate of 5.2 Hz) at the very last day of stimulation. Therefore, it may be the stimulation at the highest possible rate, and not the rate per se, that is the governing cue for cardiomyocyte maturation in vitro.

Improved cell and myofilament structure in stimulated conditions, with clearly visible Z discs, H zones and I bands, correlated with better electrical properties of stimulated biowires such as lower ET, higher MCR, higher conduction velocity, improved electrophysiological and Ca2+ handling properties, and upregulation of potassium inwardly-rectifying channel gene (KCNJ2). Lack of M-lines and T-tubules, consistent with previous reports32,33, indicated absence of terminal differentiation. Although there was a downregulation of structural proteins mRNA in biowires compared to EBs, no changes were observed in protein levels (Supplementary Results). Mechanical stimulation was reported to lead to a robust induction of structural proteins such as myosin heavy chain and induce proliferation of hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes14,34, suggesting that electrical stimulation of biowire at 6 Hz did not simply provide a better mechanical stimulation environment. Previously, mechanical stimulation did not lead to electrophysiological maturation34. The use of electrical stimulation in conjunction with stretch as a mimic of cardiac load14, concurrently or sequentially, might be required to induce terminal differentiation in hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and upregulate the expression of myofilament proteins. Other strategies might include cultivation in the presence of T3 thyroid hormone35, insulin like growth factor-136, addition of laminin or native decellularized heart ECM into the hydrogel mixture37 and cultivation on stiffer substrates38,39.

It is well accepted that some human stem cell lines are more cardiomyogenic than others12,16 and these differences could also be related to the maturity of the produced cells. In previous reports10,11,40, many and usually most cells were irresponsive to caffeine at the end of differentiation. Therefore, differences in Ca2+ handling properties could also be due to cell line variability. Here, we demonstrated that within a given cell line, culture in biowires and electrical field stimulation enhanced Ca2+ handling properties of cardiomyocytes consistent with a functional sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Biowire cardiomyocytes were clearly more mature than cardiomyocytes obtained from EBd20 or EBd44, which showed a greater propensity for automaticity, more depolarized membrane potentials, reduced cell capacitance and less hERG and IK1 currents. The electrophysiological measurements of the EBd20 cardiomyocytes represented the cell properties prior to their incorporation into biowires, while EBd44 cardiomyocytes were cultured for periods slightly longer than the biowire culture time allowing assessment of the independent effect of culture time on maturation54,11. We acknowledge that the degree of biowire maturation is clearly incomplete, as evidenced by the relatively low membrane conductance. Nevertheless, it is intriguing to speculate that the combination of low membrane conductance with Vrest below EK may represent an “intermediate” phenotype as cardiomyocytes undergo maturation from the embryonic state.

Correlating the properties of hPSC-cardiomyocytes in biowires with mouse or human development could be helpful to gauge maturation stage, however rodent cardiomyocytes are physiologically distinct and age-defined healthy human heart samples are scarce. Additionally, in vitro maturation might not be compatible with embryo development.

The small size (radius of ~300 μm) of biowire upon gel compaction was selected to be close to the diffusional limitations for oxygen supply to ensure that the biowires can be maintained in culture without perfusion. Addition of vascular cells will be imperative for improving survival and promoting integration with the host tissue in future in vivo studies14. We have now generated a unique platform that enables generation of human cardiac tissues of graded levels of maturation that can be used to determine, in future in vivo studies, the optimal maturation level that will result in the highest ability of cells to survive and integrate in adult hearts with the lowest side effects (e.g. arrhythmias).

In conclusion, cultivation in biowires 1) improved hESC-cardiomyocyte architecture and induced physiological hypertrophy, 2) induced sarcomere maturation and 3) improved electrophysiological properties in a stimulation frequency dependent manner, representing an important first step towards obtaining adult-like human cardiomyocytes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank P. Lai, C. Laschinger, N. Dubois and B. Calvieri for technical assistance, C. C. Chang and L. Fu for their kind assistance with biowire setup figure preparation. The authors wish to acknowledge the following funding sources: ORF-GL2 grant, NSERC Strategic Grant (STPGP 381002-09), NSERC-CIHR Collaborative Health Research Grant (CHRPJ 385981-10), NSERC Discovery Grant (RGPIN 326982-10) and Discovery Accelerator Supplement (RGPAS 396125-10).

Footnotes

Author contributions: S.S.N. developed biowire concept, designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and prepared manuscript. J.W.M. performed experiments and analyzed data. J.L, R.S and P.H.B. performed patch clamping and microelectrode recordings. Y.X. designed and validated initial device. B.Z. designed and fabricated masters for device fabrication. J.J. and G.G performed calcium transient measurement and analysis. S.M and K.N. performed optical mapping measurements and analysis. M.G and G.K. differentiated hESC-derived cardiomyocytes. A.H designed primers. N.T. developed initial collagen gel mixture. M.A.L. provided training on hiPSC differentiation and cells. M.R. envisioned biowire concept and electrical stimulation protocol, supervised work and wrote manuscript.

Competing financial interests: M. A. Laflamme is a co-founder and scientific advisor for BEAT BioTherapeutics Corp.

References

- 1.Kehat I, et al. Human embryonic stem cells can differentiate into myocytes with structural and functional properties of cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:407–414. doi: 10.1172/JCI12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang L, et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, et al. Functional cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circ Res. 2009;104:e30–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kattman SJ, et al. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvajal-Vergara X, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived models of LEOPARD syndrome. Nature. 2010;465:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature09005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Heart regeneration. Nature. 2011;473:326–335. doi: 10.1038/nature10147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snir M, et al. Assessment of the ultrastructural and proliferative properties of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2355–2363. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00020.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDevitt TC, Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Proliferation of cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells is mediated via the IGF/PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:865–873. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mummery C, et al. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to cardiomyocytes: role of coculture with visceral endoderm-like cells. Circulation. 2003;107:2733–2740. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000068356.38592.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolnikov K, et al. Functional properties of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: intracellular Ca2+ handling and the role of sarcoplasmic reticulum in the contraction. Stem Cells. 2006;24:236–245. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doss MX, et al. Maximum diastolic potential of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes depends critically on I(Kr) PLoS One. 2012;7:e40288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Fu JD, Siu CW, Li RA. Functional sarcoplasmic reticulum for calcium handling of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: insights for driven maturation. Stem Cells. 2007;25:3038–3044. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satin J, et al. Calcium handling in human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1961–1972. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tulloch NL, et al. Growth of engineered human myocardium with mechanical loading and vascular coculture. Circ Res. 2011;109:47–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caspi O, et al. Tissue engineering of vascularized cardiac muscle from human embryonic stem cells. Circ Res. 2007;100:263–272. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000257776.05673.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chien KR, Knowlton KU, Zhu H, Chien S. Regulation of cardiac gene expression during myocardial growth and hypertrophy: molecular studies of an adaptive physiologic response. FASEB J. 1991;5:3037–3046. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.15.1835945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank D, et al. Gene expression pattern in biomechanically stretched cardiomyocytes: evidence for a stretch-specific gene program. Hypertension. 2008;51:309–318. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuwahara K, et al. NRSF regulates the fetal cardiac gene program and maintains normal cardiac structure and function. EMBO J. 2003;22:6310–6321. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nuccitelli R. Endogenous ionic currents and DC electric fields in multicellular animal tissues. Bioelectromagnetics Suppl. 1992;1:147–204. doi: 10.1002/bem.2250130714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson DJ, Chaudhry B. Getting to the heart of planar cell polarity signaling. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:460–467. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao M, Forrester J, McCaig C. A small, physiological electric field orients cell division. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:4942–4948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radisic M, et al. Functional assembly of engineered myocardium by electrical stimulation of cardiac myocytes cultured on scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18129–18134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407817101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger HJ, et al. Continual electric field stimulation preserves contractile function of adult ventricular myocytes in primary culture. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H341–349. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.1.H341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borg TK, et al. Specialization at the Z line of cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46:277–285. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bird SD, et al. The human adult cardiomyocyte phenotype. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:423–434. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frey N, Olson EN. Cardiac hypertrophy: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:45–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Huang Y, Ning Q. Review on regulation of inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2011;21:303–311. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v21.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dubois NC, et al. SIRPA is a specific cell-surface marker for isolating cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1011–1018. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Weer P, Gadsby DC, Rakowski RF. Voltage dependence of the Na-K pump. Annu Rev Physiol. 1988;50:225–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakai R, Hagiwara N, Matsuda N, Kassanuki H, Hosoda S. Sodium--potassium pump current in rabbit sino-atrial node cells. J Physiol. 1996;490 ( Pt 1):51–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arduini D. Fetal Cardiac Function. Parthenon Publishing Group; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lieu DK, et al. Absence of transverse tubules contributes to non-uniform Ca(2+) wavefronts in mouse and human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:1493–1500. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baharvand H, Azarnia M, Parivar K, Ashtiani SK. The effect of extracellular matrix on embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaaf S, et al. Human engineered heart tissue as a versatile tool in basic research and preclinical toxicology. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chattergoon NN, et al. Thyroid hormone drives fetal cardiomyocyte maturation. FASEB J. 2012;26:397–408. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-179895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMullen JR, et al. The insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor induces physiological heart growth via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase(p110alpha) pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4782–4793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seif-Naraghi SB, et al. Safety and efficacy of an injectable extracellular matrix hydrogel for treating myocardial infarction. Science translational medicine. 2013;5:173ra125. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez AG, Han SJ, Regnier M, Sniadecki NJ. Substrate stiffness increases twitch power of neonatal cardiomyocytes in correlation with changes in myofibril structure and intracellular calcium. Biophys J. 2011;101:2455–2464. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hazeltine LB, et al. Effects of substrate mechanics on contractility of cardiomyocytes generated from human pluripotent stem cells. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:508294. doi: 10.1155/2012/508294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blazeski A, et al. Electrophysiological and contractile function of cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2012;110:178–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.