Abstract

Background and Aims

Rootless carnivorous plants of the genus Utricularia are important components of many standing waters worldwide, as well as suitable model organisms for studying plant–microbe interactions. In this study, an investigation was made of the importance of microbial dinitrogen (N2) fixation in the N acquisition of four aquatic Utricularia species and another aquatic carnivorous plant, Aldrovanda vesiculosa.

Methods

16S rRNA amplicon sequencing was used to assess the presence of micro-organisms with known ability to fix N2. Next-generation sequencing provided information on the expression of N2 fixation-associated genes. N2 fixation rates were measured following 15N2-labelling and were used to calculate the plant assimilation rate of microbially fixed N2.

Key Results

Utricularia traps were confirmed as primary sites of N2 fixation, with up to 16 % of the plant-associated microbial community consisting of bacteria capable of fixing N2. Of these, rhizobia were the most abundant group. Nitrogen fixation rates increased with increasing shoot age, but never exceeded 1·3 μmol N g–1 d. mass d–1. Plant assimilation rates of fixed N2 were detectable and significant, but this fraction formed less than 1 % of daily plant N gain. Although trap fluid provides conditions favourable for microbial N2 fixation, levels of nif gene transcription comprised <0·01 % of the total prokaryotic transcripts.

Conclusions

It is hypothesized that the reason for limited N2 fixation in aquatic Utricularia, despite the large potential capacity, is the high concentration of NH4-N (2·0–4·3 mg L–1) in the trap fluid. Resulting from fast turnover of organic detritus, it probably inhibits N2 fixation in most of the microorganisms present. Nitrogen fixation is not expected to contribute significantly to N nutrition of aquatic carnivorous plants under their typical growth conditions; however, on an annual basis the plant–microbe system can supply nitrogen in the order of hundreds of mg m–2 into the nutrient-limited littoral zone, where it may thus represent an important N source.

Keywords: Aldrovanda vesiculosa, aquatic carnivorous plants, Utricularia vulgaris, U. australis, U. intermedia, U. reflexa, daily nitrogen gain, N nutrition, 15N2 labelling, nitrogen fixation, periphyton, traps

INTRODUCTION

The ecological group of aquatic carnivorous plants consists of about 50 species of the genus Utricularia (Lentibulariaceae), plus Aldrovanda vesiculosa (Droseraceae; Taylor, 1989; Adamec, 2011a). With the exception of a few rheophytic Utricularia species growing in fast-flowing streams, aquatic carnivorous species grow in standing, usually humic (dystrophic) waters, often under limited nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) or potassium supply (for reviews see Adamec, 1997, 2008, 2009; Guisande et al., 2007). Morphologically, most species of aquatic carnivorous plants have a linear, modular and fairly regular shoot structure, consisting of nodes with finely dissected leaves and thin cylindrical internodes; the nodes can bear branches (Friday, 1989; Taylor, 1989). Most species have undifferentiated, homogeneous green shoots bearing traps (e.g. A. vesiculosa, U. vulgaris), while in some species (e.g. U. intermedia) heterogeneous shoots occur, differentiated into green photosynthetic shoots without traps and pale carnivorous ones with traps. Unlike terrestrial carnivorous plants, all aquatic carnivorous species are rootless and many of them exhibit very rapid apical shoot growth (1–4·2 leaf nodes per day) and high relative growth rate (the time of biomass doubling is usually 7–20 d; Friday, 1989; Adamec, 2000, 2009, 2010, 2011a; Pagano and Titus, 2007). This very rapid growth in nutrient-poor waters requires several ecophysiological adaptations, including very high net photosynthetic rate of shoots, carnivory, efficient nutrient re-utilization (recycling) from senescent shoots, very high affinity for mineral nutrient uptake from ambient water and, possibly, the activity of microbial commensals inside traps in Utricularia (Adamec, 2000, 2006, 2008, 2009; Richards, 2001; Englund and Harms, 2003; Díaz-Olarte et al., 2007; Sirová et al., 2009).

In contrast to Aldrovanda with its snapping traps, the traps of aquatic Utricularia are closed hollow bladders with a negative pressure inside, usually 1–5 mm long and filled with trap fluid, which attract, capture and digest prey of suitable size (e.g. Richards, 2001; Englund and Harms, 2003; Díaz-Olarte et al., 2007; Peroutka et al., 2008; Sirová et al., 2009; Adamec, 2011b). Traps also support diverse microbial communities living in association with the plant and benefiting from carbon-rich plant exudates (Richards, 2001; Sirová et al., 2009, 2010, 2011; Płachno et al., 2012). Traps were shown to contain the members of a complex microbial food web, with bacteria forming more than 58 % of the viable microbial biomass in the trap fluid. Aquatic carnivorous plants are adapted to a preferential uptake of NH4+ over NO3– by their shoots from the ambient water. Under favourable conditions, however, the dominant part of their seasonal N gain can be covered from prey capture (Adamec, 1997, 2000, 2008, 2011a; Fertig, 2001).

Nevertheless, aquatic Utricularia species commonly grow in waters where both mineral nutrient concentrations and prey availability are low (Richards, 2001; Adamec, 2008, 2009; Peroutka et al., 2008; Sirová et al., 2009). Other means of N acquisition were therefore suspected. Wagner and Mshigeni (1986) estimated that the shoots of African U. inflexa with associated epiphytes and trap micro-organisms were capable of fixing N2 at rates of up to 2·3 μmol g–1 [dry mass (DM)] h–1. Plant-associated N2 fixation has also been reported as a potential source of N for several terrestrial carnivorous plant species with opened pitcher or snapping traps (Prankevicius and Cameron, 2011; Albino et al., 2000), although direct utilization of microbially fixed N2 by carnivorous plants has not yet been experimentally confirmed. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria have also been detected in a beneficial association with non-carnivorous aquatic plant roots and surfaces (Zuberer, 1982; Reddy, 1987).

This information pointed to an additional pathway for aquatic carnivorous plants to acquire N in nutrient-poor environments – microbial N2 fixation. The objective of our study was to detect the presence and activity of microbial N-fixing species associated with the shoots of four aquatic Utricularia species and A. vesiculosa, to measure their N2 fixation rate using 15N2 labelling, and to assess the significance of symbiotic N2 fixation for the nutrition of the plants. The activity of diazotrophs was evaluated using the relative abundance of transcripts of genes responsible for the encoding of proteins related to the fixation of atmospheric N2 (henceforth denoted collectively as nif genes). Furthermore, we assessed the dependence of the N2 fixation rate on shoot age (i.e. density of periphyton and/or trap fluid colonization) and determined the relative contribution of traps and shoot surfaces to net shoot N2 fixation. Ammonium concentrations in the trap fluid were measured in two Utricularia species. The comparison of Utricularia (traps with commensal micro-organisms) and Aldrovanda shoots (traps without commensals) was used to determine whether N2 fixation is linked specifically to the microbial community inherent to Utricularia. Four Utricularia species cultivated under semi-natural conditions or collected in the field were compared, and sterile Utricularia shoots raised in vitro were used as controls. The ecological significance of the N2 fixation rate for the daily N gain of the plants as well as for the littoral ecosystem is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant cultivation

The experiment was conducted on the following aquatic carnivorous plants: Aldrovanda vesiculosa L. (originating from eastern Poland), Utricularia vulgaris L., U. australis R.Br., U. intermedia Hayne (all from the Czech Republic) and U. reflexa Oliv. (from Botswana). The shoot of U. intermedia is distinctly differentiated into a green photosynthetic part without traps and a pale carnivorous part bearing numerous traps (Taylor, 1989). Adult stock plants of A. vesiculosa (8–12 cm long) and U. vulgaris (60–80 cm long) were cultivated outdoors in a 2·5-m2 (water surface) plastic container and U. intermedia plants (photosynthetic shoots 15–18 cm long, carnivorous shoots 8–15 cm long) in a 0·8-m2 container which approximately simulated natural conditions (for details see Sirová et al., 2003, 2009). Adult stock plants of U. reflexa (20–40 cm long) were cultivated in a 0·8-m2 plastic container, which stood in a naturally lit greenhouse with open lateral walls for cooling (see Borovec et al., 2012). Water depth in all these containers was 25–30 cm and Carex acuta litter was used as substrate. The pH of the cultivation media was 7·0–8·1, total alkalinity 0·43–1·04 meq L–1, free CO2 0·02–0·21 mmol L–1 and electrical conductivity 19·2–37·6 mS m–1. Tap water was used as the source of water. Based on the nutrient concentration, the media were considered oligo-mesotrophic and slightly humic. The concentrations of NH4-N were between 48 and 59 μg L–1, while those of NO3-N were always below detection. Small zooplankton were added to the containers to support plant growth. All containers were slightly shaded. Adult plants of Utricularia australis (40–70 cm long) were collected from a mesotrophic bog at Ruda fishpond at Branná (Třeboňsko Biosphere Reserve, South Bohemia, Czech Republic; see Sirová et al., 2010) 1 d before the start of the experiment. Here, the pH was 6·5, total alkalinity 0·51 meq L–1, concentration of free CO2 0·37 mmol L–1, conductivity 9·0 mS m–1, concentration of NH4-N 62 μg L–1 and that of NO3-N below detection. All experimental plants were transported to the laboratory in filtered culture or natural water so as not to fill their traps with air.

Trap fluid NH4+-N concentration measurements

Utricularia vulgaris and U. reflexa plants were chosen for the estimation of NH4-N concentration in the trap fluid, due to their suitable trap size. Trap fluid from several dozen traps without any macroscopic prey from young (2nd–7th adult leaf node), middle (8th–13th leaf node) and old plant segments (13th–16th leaf node) was collected using a thin glass capillary attached to a peristaltic pump (Sirová et al., 2009). A pooled sample of approx. 250–300 μL from traps of the same age on a single plant was considered as a replicate; four independent samples from different plants were collected. Samples were immediately filtered using microcentrifuge Eppendorf vials (0·22 μm pore size). Ammonium N concentrations were determined by a standard colorimetric bis-pyrazolon method on the flow injection analyser (QuickChem 8500, Lachat, Milwaukee, WI, USA).

Bacterial 16S rRNA amplicon and RNA sequencing, data analysis

To assess the presence and diversity of N2-fixing bacterial species, U. vulgaris plants from the semi-natural culture were chosen, due to their abundant large traps from which we expected the highest yield of DNA and RNA necessary to obtain high-quality sequences. Whole trap-free shoots or excised traps (approx. 50 traps or 500 mg fresh weight) were collected, placed into liquid N and stored at –80 °C until further analysis. Nucleic acid extractions were conducted according to a modified bead-beating protocol (Urich et al., 2008). Total DNA was quantified fluorometrically using SybrGreen (Leininger et al., 2006). PCR primers (515F/806R) targeted the V4 region of the small subunit (SSU) rRNA gene, previously shown to yield accurate phylogenetic information and to have only few biases against any bacterial taxa (Liu et al., 2007; Bates et al., 2011; Bergmann et al., 2011). Each sample was amplified in triplicate, combined, quantified using Invitrogen PicoGreen (Carlsbad, CA, USA) and a plate reader, and equal amounts of DNA from each amplicon were pooled into a single 1·5-mL microcentrifuge tube. Once pooled, amplicons were cleaned up using the Ultra Clean PCR clean up kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Amplicons were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform at the Institute of Genomics and Systems Biology, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne (Chicago, IL, USA). Paired-end reads were joined using Perl scripts yielding approx. 253-bp-long amplicons. Approximately 1·8 million paired-end reads were obtained with average 66 000 reads per sample. Quality filtering of reads was applied as described previously (Caporaso et al., 2010). Reads were assigned to operational taxonomic units (OTUs, cut-off 97 % sequence identity) using a closed-reference OTU picking protocol with QIIME-implemented scripts (Caporaso et al., 2010). Reads were taxonomically assigned using the Green Genes database, release 13_5, as reference. The number of SSU genes in different bacterial species varies from one to 15 copies per genome. We therefore normalized the number of SSU gene copies according to the protocol described by Langille et al. (2013) to reflect the relative abundance of bacterial taxa. Those reads which were assigned as ‘chloroplast’ and ‘mitochondrion’ were excluded from further analyses.

To assess the actively transcribed microbial gene pool, total trap RNA was extracted using the Plant RNeasy Midi Kit (Qiagen, the Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Approximately 250 mg of fresh plant biomass was used, with traps pooled from a single plant considered as a replicate; three biological replicates were collected in total. DNA was removed from the extracts using the TurboDNAFree kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Transcriptomic eukaryotic libraries were created at the Institute of Genomics and Systems Biology, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne (Chicago, IL, USA) using standard Illumina TruSeq RNA library prep kits. DynaBeads (Invitrogen) were used to remove the eukaryotic (plant) RNA fraction in the samples for the bacterial transcriptomic libraries, which were created from the same aliquots of RNA as the eukaryotic libraries. The Apollo 324 Platform (IntegenX, Pleasanton, CA, USA) was used to complete rRNA subtraction (RiboZero Plant and RiboZero Bacteria, 1:1 ratio of host and bacterial rRNA removal solution). Enriched mRNA was reverse transcribed to create bacterial metatranscriptomic libraries using the ScriptSeq V2 kit (Epicentre, Madison, MI, USA) and sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq platform (100×100 cycle paired-end run). We obtained approx. 40 million paired-end reads per sample. Reads were quality checked, and low-quality reads and reads with ambiguous bases were trimmed. The overlapping paired-end reads were joined using PANDAseq software (Masella et al., 2012). Approximately 80 % of reads were assembled and used for further analyses. First, the eukaryotic RNA with polyA tail was removed with trim_fasta.pl script (Frias-Lopez et al., 2008). Then, 1 million sequences were randomly selected using the perl script extract_fasta_records.pl (Meneghin, 2010). Reads were blasted against SILVA database release 111 to identify rRNAs. Those sequences (approx. 5·2 % of the total sequences remained after rRNA subtraction) that had a BLAST bit score greater than 80 were marked as potential rRNAs and extracted from the dataset. To identify potential prokaryotic functional gene transcripts, the remaining sequences without rRNAs were blasted against the non-redundant database with e-value of 0·001. A Unix grep script was then used to extract blast hits related to N2 fixation.

15N2 fixation assay

Before the experiment, the plants were deprived of all branches. Shoot segments were dissected under water in a Petri dish, according to the position of adult leaf nodes, which is a precise measure of segment age (cf. Friday, 1989; Adamec, 2008). In U. vulgaris, they were: shoot growth tips including immature leaf nodes, very young shoots (3rd–6th adult nodes from the apex), middle shoots (11th–13th nodes) and old shoots (31st–33rd nodes); in U. australis: very young shoots (3rd–6th nodes) and old shoots (31st–33rd nodes); in U. reflexa: apical shoots (shoot apex with ten leaf nodes 8–12 cm long), basal shoots (11th–20th nodes 5–10 cm long), apical shoots without traps and 25–30 traps 2–6 mm long excised from the apical shoots; in U. intermedia: submerged green photosynthetic shoots (without traps, 12–15 cm long) and pale carnivorous shoots (with traps, 8–15 cm long); and in A. vesiculosa: apical shoots (shoot apex with ten nodes). As a control for estimation of the influence of periphyton and trap commensals on N2 fixation, apical parts of U. vulgaris shoots (approx. 12–15 cm long) growing in an aseptic meristem tissue culture (see Adamec and Pásek, 2009) were also used. Two to three shoot segments from different plants represented one sample, the dry mass of which amounted to 5–41 mg.

The washed sample was gently blotted dry using a soft paper tissue and, according to the size of the segments, placed into a 125-mL glass bottle (Schott, Germany) filled with 20–40 mL of the filtered (25-μm mesh size) culture water (from the outdoor container with U. vulgaris and A. vesiculosa). The pH of this medium was 7·05, total alkalinity 1·04 meq L–1, concentration of free CO2 0·21 mmol L–1, conductivity 19·2 mS m–1, NH4-N 48 μg L–1 and PO4-P 12·3 μg L–1. The bottles were closed with a gas-tight rubber stopper fastened by a plastic screw lid with a central hole allowing gas exchange through a syringe needle. Half of the gas headspace volume (42–52 mL depending on the volume of the water) was removed by a syringe and replaced by the same volume of gas mixture comprising 15N2 (99·8 at.%) and CO2 in a molar fraction of 4000 μmol (CO2) moL–1 (15N2). CO2 was added to support photosynthesis of the shoot segments. Bottles with the shoot segments or excised traps in the culture water and 15N2 in the headspace were placed in the inverted position into a growth chamber (Sanyo, UK) where the incubation continued at 23 °C and about 400 μmol (PAR) m–2 s–1 for 24 h (15/9 h light/dark). Five independent replicates of each plant material type were used. Three additional control replicates without the 15N2 addition were prepared in the same way.

15N isotope analyses

After 24 h, each bottle was opened, plant segments washed under tap water and dried 48 h at 60 °C. The samples were homogenized to fine powder using a ball mill (Retsch MM200, Haan, Germany) and 10–15 mg of DM (shoots with sufficient mass quantity) or 0·7–0·8 mg (traps and apices with low amount of DM) were taken for isotopic and total N analyses. Tissue N content and the 15N/14N ratio were analysed with an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS; Thermo Finnigan DELTAplus, Brehmen, Germany) coupled to an elemental analyser (Carlo Erba, NA1110, Milan, Italy, or Elementar, vario MICRO cube, Hanau, Germany).

The abundance of 15N in plant dry mass was expressed in the δ notation as the 15N/14N isotopic ratio of plant biomass (Rp) normalized to the isotopic ratio of N2 in the free atmosphere (Ra = 0·0036765), δ15Np = [(Rp/Ra) – 1] × 1000 in permil (‰). We used IAEA-N-1 for calibration of the laboratory gas standard. Repeated measurements of IAEA-N-1 had a standard deviation of 0·11 ‰. As the large and small samples were analysed in two different IRMS laboratories (České Budějovice, Czech Republic, and Freising, Germany), an inter-laboratory cross check test was performed on nine selected samples. The δ15Np values obtained by both laboratories and plotted against each other formed a regression line with slope of 0·892 deviating slightly from the 1:1 line (R2 = 0·991).

Calculation of N2 fixation rate

To follow the mass balance concept, we converted the δ15N values to molar fractions defined as 15N/(15N + 14N) and expressed in atom-percent (at%). δ15N is related directly to at% as follows (Montoya et al., 1996):

|

(1) |

To calculate the N2 fixation rate by the experimental plants on the DM basis, we needed to know (1) 15N abundance in the atmosphere above the water with experimental plants (headspace atmosphere enrichment in 15N), at%ea, which ranged here from 47 to 58 at% depending on the volume of added 15N2; (2) 15N abundance in the atmosphere above the water with control plants (non-enriched headspace atmosphere), at%ca, assumed to be identical to free atmosphere at%a = 0·3676; (3) 15N abundance in control plants and in plants exposed to enriched 15N atmosphere, at%cp and at%ep, respectively; and (4) total N content in plants per unit dry mass, c (mg g–1). It is useful to convert c to molar content of N per plant dry mass, N, in μmol (14N + 15N) g–1:

|

(2) |

where the subscript x stands for c in control plants or e in plants exposed to 15N-enriched atmosphere.

If the N2 dissolved in water is fixed in the course of the experiment, 15N accumulates in the experimental plants in excess compared with controls, Nep:

|

(3) |

As the only source creating the excess is the headspace 15N2 (assumed to be in equilibrium with the plant water medium), the 15N mass balance can be written as follows:

|

(4) |

It is possible to find a fraction of the 15N2 tracer fixed in experimental plants, f, by combining eqns (3) and (4):

|

(5) |

The tracer fraction f has built up during the course of the experiment. When divided by the duration of the experiment, time t, the rate of N2 fixation relative to total N content (f/t in d–1) is obtained. (The inverse value of the relative N2 fixation rate, t/f, shows the time of N turnover expected when the N2 assimilation is the only source of N gain.) f/t multiplied by total tissue N content in dry mass of the experimental plant, Nep, gives the absolute rate of N2 fixation, FN2 in μmol N g–1 (DM) d–1:

|

(6) |

After a particular time of cultivation, the plants reach a steady state when their dry matter peaks and stays constant. Should the 15N2 label still be supplied at this stage, N isotopic composition of the plants would not change, i.e. the plant would reach an isotopic steady state. Let this phase be reached after T days. The fraction of N in the steady-state plant formed by N2 fixation, fN2, and expressed in per cent is:

|

(7) |

Statistics and data deposition

Where possible, data sets were tested with either Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; Tukey post-hoc test) using the Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Raw reads were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the submission ID SUB378555 and BioProject ID PRJNA227401.

RESULTS

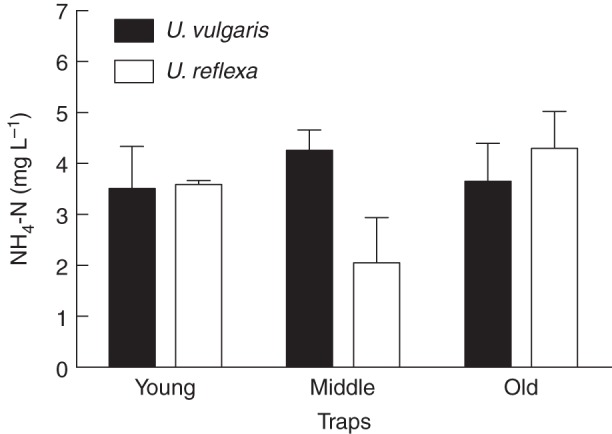

Mean trap fluid NH4-N concentrations in Utricularia vulgaris and U. reflexa usually varied slightly and non-significantly both between species and within traps of different age, ranging between 2·0 and 4·3 mg L–1 (Fig. 1), i.e. about 50–80 times higher than those in the ambient culture media. Although no clear pattern related to the age or species could be seen, the single values were high in all samples and always exceeded 0·5 mg L–1.

Fig. 1.

Ammonium nitrogen concentrations in the U. vulgaris and U. reflexa trap fluid from traps of different age. Means ± s.e. are shown (n = 4). The differences between different trap ages within one species or between both species within one trap age were not statistically significant at P < 0·05 (one-way ANOVA).

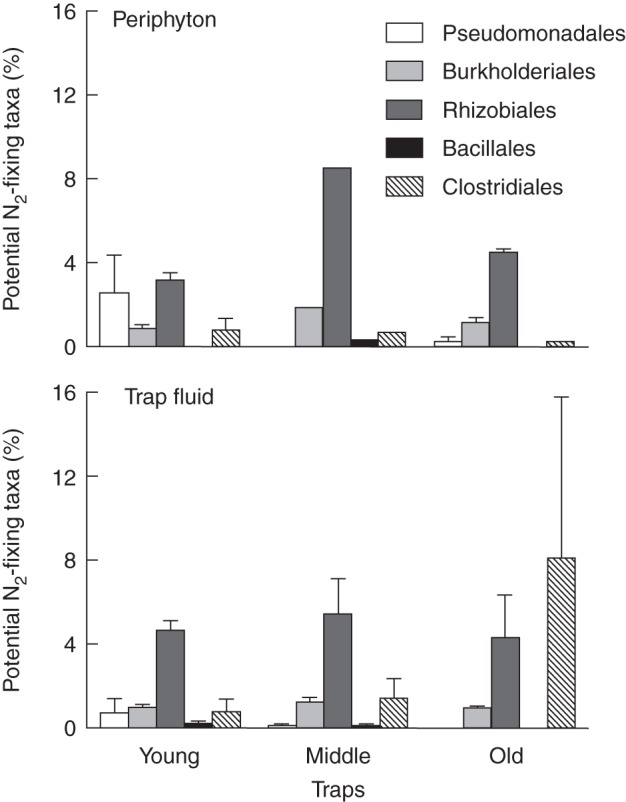

Analyses of bacterial 16S rRNA amplicons from the trap fluid and periphyton of U. vulgaris confirmed the presence of microbial taxa with previously known ability to fix N2 (Fig. 2). We identified a total of 66 bacterial OTUs in 22 families and five orders in this group. Members of Rhizobiales were the most abundant potentially diazotrophic bacteria in most samples and constituted between approx. 0·1 and 8·5 % of the total recovered bacterial sequences, depending on the treatment. Members of seven cyanobacterial families from three classes were also detected; several OTUs were assigned to the basal 4C0d-2 Cyanobacteria-like lineage. When comparing traps of various age, or the trap fluid and periphyton, no statistically significant differences in the relative abundance or composition of the diazotrophic species were found. The sequences that could be assigned to genes associated with N2 fixation constituted less than 0·01 % of the active gene transcript pool. Most N2 fixation-associated transcripts were attributed to Chitinophaga sp. from the phylum Bacteroidetes, followed by sequences attributed to uncultured, unclassified organisms, and Anabaena sp. (Cyanobacteria).

Fig. 2.

The relative abundance of potential N2-fixing taxa (% of total recovered sequences) identified in the periphyton and the trap fluid from U. vulgaris shoot segments of different age (means ± s.e. are shown, n = 3, except for middle trap fluid, where no replicates were available).

Dry matter of plants exposed to 15N2 atmosphere was significantly enriched in 15N compared with controls (Table 1). In U. vulgaris, for instance, the δ15N increased from an average of 0·37‰ in controls to 3·71‰ in 15N2-exposed apices and to 33·8‰ in 15N2-exposed basal shoot parts. The 15N enrichment increased gradually from young apical parts of the shoots toward their base in all investigated Utricularia species and was up to 15 times higher in the carnivorous shoots with traps than in the photosynthetic trap-free shoots in U. intermedia. The tissue N content in experimental plants ranged between 1·1 and 2·7 % DM and gradually declined from shoot apices towards shoot bases in single species.

Table 1.

Total tissue N content (% dry mass, DM) and δ15N values in control plant tissues and plants exposed to 15N-enriched atmosphere (δ15Nc and δ15Ne, respectively) for all experimental plants and treatments; means ± s.e. are shown (n = 5)

| Species, treatment | N (% DM) | δ15Nc (‰) | δ15Ne (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|

| U. vulgaris, growth tips | 2·68 ± 0·36 | 2·89 ± 1·10 | 3·71 ± 0·99 |

| U. vulgaris, apical shoot segments | 1·62 ± 0·22 | 1·76 ± 0·28 | 9·43 ± 5·60 |

| U. vulgaris, middle shoot segments | 1·35 ± 0·21 | 2·36 ± 0·68 | 18·7 ± 7·96 |

| U. vulgaris, basal shoot segments | 1·08 ± 0·10 | 2·43 ± 0·64 | 33·8 ± 15·8 |

| U. vulgaris, sterile shoots | 1·98 ± 0·04 | –18·1 ± 0·62 | –21·8 ± 0·36 |

| U. reflexa, apical shoot segments | 1·85 ± 0·16 | 6·55 ± 0·36 | 98·0 ± 71·3 |

| U. reflexa, basal shoot segments | 1·59 ± 0·27 | 5·70 ± 0·32 | 162 ± 36·8 |

| U. reflexa, trap-free shoots | 2·23 ± 0·15 | 6·06 ± 0·41 | 37·3 ± 34·8 |

| U. reflexa, traps (excised) | 1·66 ± 0·09 | 5·8 ± 0·33 | 81·8 ± 54·5 |

| U. australis, apical shoot segments | 2·40 ± 0·32 | 5·65 ± 0·38 | 11·8 ± 3·02 |

| U. australis, basal shoot segments | 2·11 ± 0·20 | 4·43 ± 1·48 | 49·4 ± 29·5 |

| U. intermedia, photosynthetic shoots | 2·37 ± 0·07 | 3·11 ± 0·10 | 6·08 ± 2·21 |

| U. intermedia, carnivorous shoots | 1·46 ± 0·12 | 2·84 ± 0·05 | 92·7 ± 28·3 |

| A. vesiculosa, entire shoots | 1·89 ± 0·18 | 2·00 ± 0·16 | 6·68 ± 0·90 |

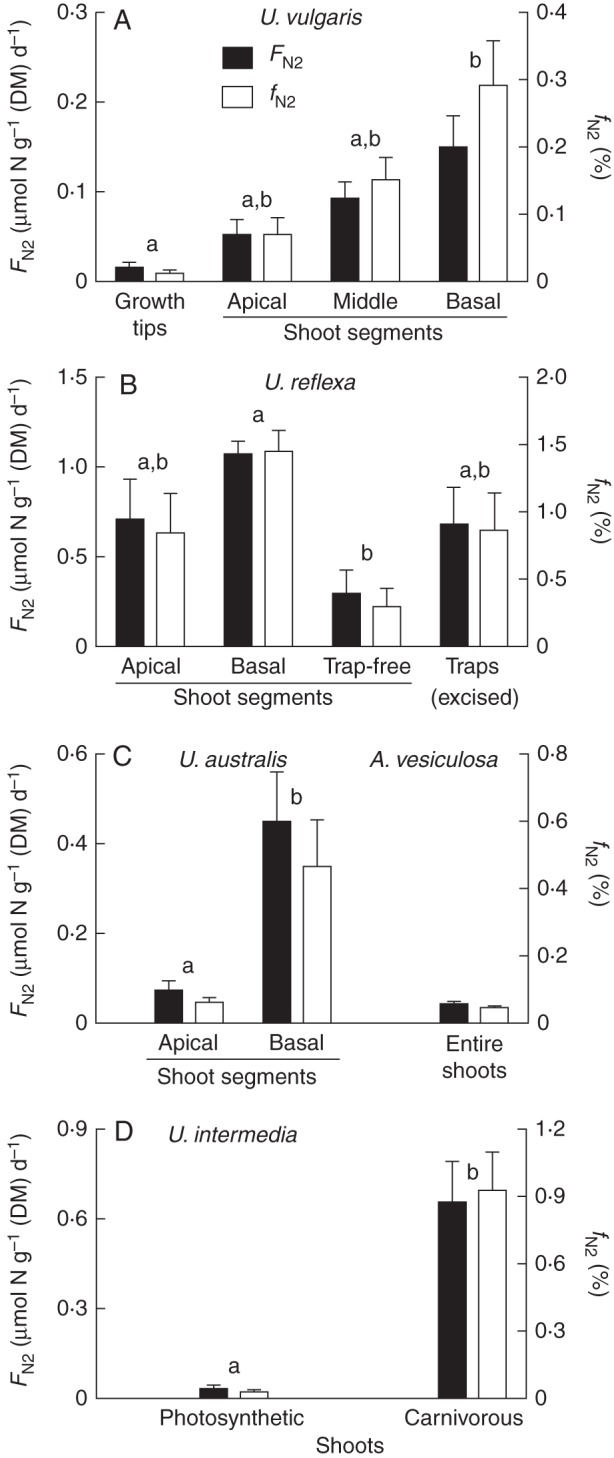

Differences in δ15N between controls and 15N2-treated plants were converted into the linearly related N2-fixation rates, FN2, using eqn (6). The data clearly show gradients of N2 uptake with FN2 values increasing from the youngest apical tissue toward the oldest basal shoot segments in U. vulgaris, U. reflexa and U. australis (Fig. 3A–C) and indicate the dominant role of traps in U. reflexa and U. intermedia (Fig. 3B and D, respectively).

Fig. 3.

Fixation rates of atmospheric N2 (FN2, left vertical axes) and its fraction in the total plant N (fN2, right vertical axes) in different shoot segments or organs of four Utricularia species and in Aldrovanda. Means ± s.e. are shown; n = 5; distinct letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0·05). ‘Traps’ denotes traps excised from shoots in U. reflexa, while ‘trap-free’ denotes samples consisting of apical shoots with excised traps; ‘photosynthetic’ and ‘carnivorous’ denote photosynthetic trap-free shoots and pale carnivorous shoots with traps of U. intermedia, respectively.

Despite low FN2 values, all below 1 μmol fixed N g–1 (DM) d–1, the N2 assimilation rate was detectable and significant. The fraction of N fixed from the atmosphere, calculated using eqn (7), did not exceed 1·5 % and mostly formed less than 1 % of the total plant N (Fig. 3). Again, basal shoot segments and traps were confirmed to be the dominant organs to fix and accumulate atmospheric N. Interestingly, the entire Aldrovanda shoots with snapping traps exhibited a minimum N2 fixation activity (Fig. 3C).

DISCUSSION

Although low, N2 fixation was detectable in all our experimental aquatic carnivorous plants. The comparison of trap-free shoots and traps in U. reflexa and U. intermedia has shown that the trap lumen is the dominant site of N2 fixation. When comparing the N2 fixation rates for U. reflexa shoots and traps (Fig. 3B) and assuming a 60 % proportion of traps to total shoot DM (L. Adamec, unpubl. res.), then the proportion of trap-associated N2 fixation to the total shoot N2 fixation is approx. 80 %. The only exceptions among our experimental plants without any detected 15N enrichment and no positive N2 fixation rate were the sterile U. vulgaris plants: the 15N2-exposed plants were even slightly more depleted than controls (Table 1). Moreover, both treated and control sterile plants had markedly lower δ15N than all other non-sterile plants, probably caused by inorganic N salts depleted in 15N in the sterile mineral nutrient solution.

The absence of 15N2 fixation in sterile plants clearly points to the involvement of microbial diazotrophs. Indeed, our results showed that there was a significant fraction of bacteria associated with U. vulgaris traps that are potentially capable of fixing atmospheric N2 (Fig. 2). The most abundant group – the Rhizobiales – are well known for their symbiotic association with leguminous plants. Others, such as members of the Pseudomonadales and Burkholderiales, are ubiquitous in soil and many are known to have plant growth-promoting activity (Vessey, 2003; Drogue et al., 2012). These groups were also present in the plant periphyton and no significant differences were found between the traps and shoots in the composition and abundance of the diazotrophic community members at the level of microbial order. This is consistent with previous results, which showed that the trap community is highly similar to that of the periphyton on the same plant, where it most probably originates (Sirová et al., 2009). We attribute the N2 fixation associated with trap-free shoots to periphytic micro-organisms, but endophytes could also play a role. It has been shown that endophytic diazotrophs such as Azospirillum, Burkholderia, Enterobacter and Pseudomonas could supply up to 40 % of N to field-grown sweet potato plants (Yoneyama et al., 1998). These genera were also present in our U. vulgaris samples.

Although for technical reasons we have only applied molecular tools to study the proportion of diazotrophs in the traps of one Utricularia species, we expect similar patterns at the lower taxonomical resolution to occur in others, as the trap lumen of different aquatic Utricularia is known to have similar physico-chemical properties. These include stable pH, low dissolved oxygen concentrations, high concentration of easily degradable dissolved organic carbon and high P content (Sirová et al., 2003, 2009, 2010, 2011; Adamec, 2007; Borovec et al., 2012). All of these factors are known to be favourable for the highly energetically demanding N2 fixation process (Martinez-Argudo et al., 2005). However, neither the analysis of the actively transcribed N2 fixation-associated genes nor the 15N labelling results have confirmed that N2 fixation represents a significant ecological benefit for the plants. The nitrogen fixation rates shown in Fig. 3 for the different species do not exceed 1·3 μmol N g–1 (DM) d–1, while N2 fixation rates in root nodules (López et al., 2008), in soil rhizosphere (Černá et al., 2009) or those associated with aquatic macrophytes such as Lemna (Zuberer, 1982) or Azolla (Reddy, 1987) are commonly one to two orders of magnitude higher. The fixation rates in A. vesiculosa were comparable with those observed in U. intermedia trap-free photosynthetic shoots, and can be attributed to the peri/endophytic communities.

In U. vulgaris, U. reflexa and U. australis, there was a marked increase of the N2 fixation rates with increasing shoot age. This is in agreement with previously published results which show that the total microbial biomass is significantly larger in older traps (Sirová et al., 2009). This pattern is also reflected in the fraction of N2-originating N in the total plant tissue N pool, although it does not exceed 1·5 % in any of the studied species, not even in the oldest tissues, and is therefore unlikely to be of significant benefit to plant N acquisition. Because plant tissues used in the analysis were contaminated by the presence of micro-organisms labelled by 15N, the 1·5 % plant uptake is probably an overestimate, and represents a theoretical maximum for this study. This is confirmed by a model based on exponential plant growth [doubling time of biomass of 15 d and/or the daily DM increase of 4·73 %, 2 % N in plant DM, daily N gain of 68 μmol N g–1 (DM), 1 μmol of fixed N g–1 (DM) d–1; see Table 1, this study; Adamec, 2011a] and on the assumption that, due to the fast turnover or organic matter in traps, most of the N2 fixed within the lumen will be utilized by the plant. It similarly suggests that only approx. 1·5 % of the daily Utricularia N gain could theoretically be covered by this N2 fixation rate.

It has been well documented previously that microbial N2 fixation is inversely related to the concentration of available mineral N (Howarth et al., 1988; Vitousek et al., 2002). Surprisingly little is known about its concentration in the trap fluid of terrestrial carnivorous species with pitcher traps, although these are important model organisms in ecological studies (e.g. Butler et al., 2008; Mouquet et al., 2008; Baiser et al., 2013). Judging from the response of these plants to N addition, however, it can be assumed that these species tend to be N-limited (Ellison and Gotelli, 2002). Aquatic Utricularia therefore stands apart in the carnivorous plants group: we hypothesize that the reason for the limited associated N2 fixation is the high NH4-N concentration (2·0–4·3 mg L–1) in their traps (Fig. 1), which probably inhibits N2 fixation in most micro-organisms present.

The subunits of the main enzyme of the N2 fixation process – nitrogenase – are encoded by nif genes, and the nifH gene encodes dinitrogen reductase, one of the nitrogenase components in N2-fixing bacteria. In many diazotrophs, nitrogenase activities correspond well with the levels of nifH transcription (Terakado-Tonooka et al., 2013), which were very low in all our samples. The trap internal environment is rather heterogeneous, with numerous organic detritus particles of various sizes and shapes in different stages of decomposition (Richards, 2001; Peroutka et al., 2008; Sirová et al., 2009; Płachno et al., 2012); this probably results in numerous microhabitats or niches colonized by different microbes, as is the case in the water column, sediments or sedimenting organic flocks (Long and Azam, 2001). Although the concentration of NH4-N in most traps is comparable with that in hypertrophic waters or waste waters, and probably inhibits N2 fixation, certain trap microhabitats may experience reduced substrate diffusion and hence harbour microorganisms actively fixing N2. This may be the case of Chitinophaga spp., which were found to be the most active diazotrophs in U. vulgaris traps.

It has been suggested previously that Utricularia traps are primarily used to enhance the acquisition of P rather than N (Sirová et al., 2003, 2009; Ibarra-Laclette et al., 2011). Ibarra-Laclette et al. (2011), in their analysis of the U. gibba transcriptome, have proposed that a significant proportion of N uptake may be channelled via the vegetative parts. This could explain why trap N concentrations (both NH4-N and organic dissolved N) are consistently high, even in species growing in highly oligotrophic waters with low prey-capture rates (this study; Sirová et al., 2009, 2011).

In conclusion, the high trap NH4-N concentrations, most probably resulting from rapid organic detritus turnover and low affinity for ammonium uptake of trap tissues, probably inhibit the expression of microbial nif genes. Although diazotrophs associated with trap lumen constitute a significant part of the microbial community, the possibility of a significant contribution by the N2 fixation process to the nutrition of aquatic Utricularia under their typical growth conditions is unlikely. Despite this, when considering, for instance, typical U. australis stands (dozens of g DM m–2), from which the plants for this study were collected, and the average N2 fixation rate for this species of approx. 0·3 μmol N g–1 (DM) d–1 (Fig. 3C), it is apparent that hundreds of mg N m–2 can be supplied by the plant–microbe system yearly. This may not seem a lot, but it may represent an important N source in the nutrient-limited littoral zone at Utricularia sites.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Czech Scientific Foundation project No. P504/11/0783 and partly by the long-term research development project No. RVO 67985939 (L.A.). Sincere thanks are due to Brian G. McMillan for correction of the English text. Special thanks are due to two anonymous referees for valuable comments that helped to improve the manuscript. Access to computing and storage facilities owned by parties and projects contributing to the National Grid Infrastructure MetaCentrum, provided under the programme ‘Projects of Large Infrastructure for Research, Development, and Innovations’ (LM2010005), is greatly acknowledged. We are grateful to the IGSB-NGS Sequencing Core at Argonne National Laboratory for preparing the metatranscriptomic libraries and completing the sequencing.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adamec L. Photosynthetic characteristics of the aquatic carnivorous plant Aldrovanda vesiculosa. Aquatic Botany. 1997;59:297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Adamec L. Rootless aquatic plant Aldrovanda vesiculosa: physiological polarity, mineral nutrition, and importance of carnivory. Biologia Plantarum. 2000;43:113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Adamec L. Respiration and photosynthesis of bladders and leaves of aquatic Utricularia species. Plant Biology. 2006;8:765–769. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamec L. Oxygen concentrations inside the traps of the carnivorous plants Utricularia and Genlisea (Lentibulariaceae) Annals of Botany. 2007;100:849–856. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamec L. Mineral nutrient relations in the aquatic carnivorous plant Utricularia australis and its investment in carnivory. Fundamental and Applied Limnology. 2008;171:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Adamec L. Photosynthetic CO2 affinity of the aquatic carnivorous plant Utricularia australis (Lentibulariaceae) and its investment in carnivory. Ecological Research. 2009;24:327–333. [Google Scholar]

- Adamec L. Field growth analysis of Utricularia stygia and U. intermedia – two aquatic carnivorous plants with dimorphic shoots. Phyton. 2010;49:241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Adamec L. Ecophysiological look at plant carnivory: why are plants carnivorous? In: Seckbach J, Dubinski Z, editors. All flesh is grass. Plant–animal interrelationships. Cellular Origin, Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology. Vol. 16. Dordrecht: Springer Science + Business Media B. V; 2011a. pp. 455–489. [Google Scholar]

- Adamec L. Functional characteristics of traps of aquatic carnivorous Utricularia species. Aquatic Botany. 2011b;95:226–233. [Google Scholar]

- Adamec L, Pásek K. Photosynthetic CO2 affinity of aquatic carnivorous plants growing under nearly-natural conditions and in vitro. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter. 2009;38:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Albino U, Saridakis DP, Ferreira MC, Hungria M, Vinuesa P, Andrade G. High diversity of diazotrophic bacteria associated with the carnivorous plant Drosera villosa var. villosa growing in oligotrophic habitats in Brazil. Plant and Soil. 2000;287:199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Baiser B, Buckley HL, Gotelli NJ, Ellison AM. Predicting food-web structure with metacommunity models. Oikos. 2013;122:492–506. [Google Scholar]

- Bates ST, Berg-Lyons D, Caporaso JG, Walters WA, Knight R, Fierer N. Examining the global distribution of dominant archaeal populations in soil. ISME Journal. 2011;5:908–917. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann GT, Bates ST, Eilers KG, et al. The under-recognized dominance of Verrucomicrobia in soil bacterial communities. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2011;43:1450–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovec J, Sirová D, Adamec L. Light as a factor affecting the concentration of simple organics in the traps of aquatic carnivorous Utricularia species. Fundamental and Applied Limnology. 2012;181:159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Butler JL, Gotelli NJ, Ellison AM. Linking the brown and green: nutrient transformation and fate in the Sarracenia microecosystem. Ecology. 2008;89:898–904. doi: 10.1890/07-1314.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Černá B, Rejmánková E, Snyder JM, Šantrůčková H. Heterotrophic nitrogen fixation in oligotrophic tropical marshes: changes after phosphorus addition. Hydrobiologia. 2009;627:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Olarte J, Valoyes-Valois V, Guisande C, et al. Periphyton and phytoplankton associated with the tropical carnivorous plant Utricularia foliosa. Aquatic Botany. 2007;87:285–291. [Google Scholar]

- Drogue B, Dore H, Borland S, Wisniewski-Dyé F, Prigent-Combaret C. Which specificity in cooperation between phytostimulating rhizobacteria and plants? Research in Microbiology. 2012;163:500–510. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison AM, Gotelli NJ. Nitrogen availability alters the expression of carnivory in the northern pitcher plant, Sarracenia purpurea. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2002. pp. 4409–4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund G, Harms S. Effects of light and microcrustacean prey on growth and investment in carnivory in Utricularia vulgaris. Freshwater Biology. 2003;48:786–794. [Google Scholar]

- Fertig B. Waltham, MA, USA: Student report, Brandeis University; 2001. Importance of prey derived and absorbed nitrogen to new growth; preferential uptake of ammonia or nitrate for three species of Utricularia. [Google Scholar]

- Frias-Lopez J, Shi Y, Tyson GW, et al. Microbial community gene expression in ocean surface waters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2008. pp. 3805–3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friday LE. Rapid turnover of traps in Utricularia vulgaris L. Oecologia. 1989;80:272–277. doi: 10.1007/BF00380163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guisande C, Granado-Lorencio C, Andrade-Sossa C, Duque SR. Bladderworts. Functional Plant Science and Biotechnology. 2007;1:58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth RW, Marino R, Cole JJ. Nitrogen-fixation in fresh-water, estuarine, and marine ecosystems 2. Biogeochemical controls. Limnology and Oceanography. 1988;33:688–701. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra-Laclette E, Albert VA, Perez-Torres CA, et al. Transcriptomics and molecular evolutionary rate analysis of the bladderwort (Utricularia), a carnivorous plant with a minimal genome. BMC Plant Biology. 2011;11:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langille MGI, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nature Biotechnology. 2013;31:814. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger S, Urich T, Schloter M, et al. Archaea predominate among ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in soils. Nature. 2006;442:806–809. doi: 10.1038/nature04983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Lozupone C, Hamady M, Bushman FD, Knight R. Short pyrosequencing reads suffice for accurate microbial community analysis. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;35:e120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long RA, Azam F. Microscale patchiness of bacterioplankton assemblage richness in seawater. Aquatic Microbial Ecology. 2001;26:103–113. [Google Scholar]

- López M, Herrera-Cervera JA, Iribarne C, Tejera NA, Lluch C. Growth and nitrogen fixation in Lotus japonicus and Medicago truncatula under NaCl stress: Nodule carbon metabolism. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2008;165:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Argudo I, Little R, Shearer N, Johnson P, Dixon R. Nitrogen fixation: key genetic regulatory mechanisms. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2005;33:152–156. doi: 10.1042/BST0330152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masella AP, Bartram AK, Truszkowski JM, Brown DG, Neufeld JD. PANDAseq: paired-end assembler for Illumina sequences. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneghin J. 2010. http://alrlab.research.pdx.edu/aquificales/scripts/extract_fasta_records.pl. accessed 4 November 2013.

- Montoya JP, Voss M, Kähler P, Capone DG. A simple, high-precision, high-sensitivity tracer assay for N2 fixation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1996;62:986–993. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.986-993.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouquet N, Daufresne T, Gray SM, Miller TE. Modelling the relationship between a pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea) and its phytotelma community: mutualism or parasitism? Functional Ecology. 2008;22:728–737. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano AM, Titus JE. Submersed macrophyte growth at low pH: carbon source influences response to dissolved inorganic carbon enrichment. Freshwater Biology. 2007;52:2412–2420. [Google Scholar]

- Peroutka M, Adlassnig W, Volgger M, Lendl T, Url WG, Lichtscheidl IK. Utricularia: a vegetarian carnivorous plant? Algae as prey of bladderwort in oligotrophic bogs. Plant Ecology. 2008;199:153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Płachno BJ, Łukaszek M, Wołowski K, Adamec L, Stolarczyk P. Aging of Utricularia traps and variability of microorganisms associated with that microhabitat. Aquatic Botany. 2012;97:44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Prankevicius AB, Cameron DM. Bacterial dinitrogen fixation in the leaf of the northern pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea) Canadian Journal of Botany. 2011;69:2296–2298. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KR. Nitrogen fixation by Azolla cultured in nutrient enriched waters. Journal of Aquatic Plant Management. 1987;25:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Richards JH. Bladder function in Utricularia purpurea (Lentibulariaceae): is carnivory important? American Journal of Botany. 2001;88:170–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirová D, Adamec L, Vrba J. Enzymatic activities in traps of four aquatic species of the carnivorous genus Utricularia. New Phytologist. 2003;159:669–675. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirová D, Borovec J, Černá B, Rejmánková E, Adamec L, Vrba J. Microbial community development in the traps of aquatic Utricularia species. Aquatic Botany. 2009;90:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sirová D, Borovec J, Šantrůčková H, Šantrůček J, Vrba J, Adamec L. Utricularia carnivory revisited: plants supply photosynthetic carbon to traps. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:99–103. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirová D, Borovec J, Picek T, Adamec L, Nedbalová L, Vrba J. Ecological implications of organic carbon dynamics in the traps of aquatic carnivorous Utricularia plants. Functional Plant Biology. 2011;38:583–593. doi: 10.1071/FP11023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P. The Genus Utricularia: A Taxonomic Monograph. London: Royal Botanic Gardens; 1989. Kew Bulletin, Additional Series, XIV. [Google Scholar]

- Terakado-Tonooka J, Ando S, Ohwaki Y, Yoneyama T. NifH gene expression and nitrogen fixation by diazotrophic endophytes in sugarcane and sweet potato. In: de Bruijn F, editor. Molecular ecology of the rhizosphere. Volume 1. New York: Wiley; 2013. pp. 437–444. [Google Scholar]

- Urich T, Lanzén A, Qi J, Huson DH, Schleper C, Schuster SC. Simultaneous assessment of soil microbial community structure and function through analysis of the meta-transcriptome. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey JK. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria as biofertilizers. Plant and Soil. 2003;255:571–586. [Google Scholar]

- Vitousek PM, Cassman K, Cleveland C, et al. Towards an ecological understanding of biological nitrogen fixation. Biogeochemistry. 2002;57:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GM, Mshigeni KE. The Utricularia–Cyanophyta association and its nitrogen-fixing capacity. Hydrobiologia. 1986;141:255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama T, Terakado J, Masuda T. Natural abundance of 15N in sweet potato, pumpkin, sorghum and castor bean: possible input of N2-derived nitrogen in sweet potato. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 1998;26:152–154. [Google Scholar]

- Zuberer DA. Nitrogen fixation (acetylene reduction) associated with duckweed (Lemnaceae) mats. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1982;43:823–828. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.4.823-828.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]