Abstract

Background

The rate and risk factors of recurrent or metachronous adenocarcinoma following endoscopic ablation therapy in patients with Barrett’s esophagus (BE) have not been specifically reported.

Aims

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence and predictors of adenocarcinoma after ablation therapy for BE high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or intramucosal carcinoma (IMC).

Methods

This is a single center, retrospective review of prospectively collected data on consecutive cases of endoscopic ablation for BE. A total of 223 patients with BE (HGD or IMC) were treated by ablation between 1996 and 2011. Primary outcome measures were recurrence and new development of adenocarcinoma after ablation. Recurrence was defined as the presence of adenocarcinoma following the absence of adenocarcinoma in biopsy samples from 2 consecutive surveillance endoscopies. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess predictors of adenocarcinoma after ablation.

Results

183 patients were included in the final analysis, and 40 patients were excluded: 22 for palliative ablation, 8 lost to follow-up, 5 for residual carcinoma and 5 for postoperative state. Median follow-up was 39 months. Recurrence or new development of adenocarcinoma was found in 20 patients (11%) and the median time to recurrence/development of adenocarcinoma was 11.5 months. Independent predictors of recurrent or metachronous adenocarcinoma were hiatal hernia size ≥ 4cm (odds ratio 3.649, P = 0.0233) and histology (HGD/adenocarcinoma) after 1st ablation (odds ratio 4.141, P = 0.0065).

Conclusions

Adenocarcinoma after endoscopic therapy for HGD or IMC in BE is associated with large hiatal hernia and histology status after initial ablation therapy.

Keywords: Barrett’s esophagus, Adenocarcinoma, Recurrence, Ablation techniques, Endoscopy

Introduction

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the most significant risk factor for developing esophageal adenocarcinoma,1–3 and the prognosis of invasive esophageal adenocarcinoma remains poor.4–6 Endoscopic ablative therapy has become widely utilized as an effective technique to eliminate esophageal dysplastic mucosa and/or mucosal adenocarcinoma.7–11

A major limitation of ablation therapy of BE is recurrent and metachronous adenocarcinomas, and BE with HGD may develop to adenocarcinoma in 3–20% of patients per year.10, 12 A study by Phoa et al showed that 6% of patients treated with ablation going on to have a cancer recurrence after 5 years. 13 Furthermore, about 33% patients can have a recurrence of intestinal metaplasia or dyplastic BE.14 Because of this, close endoscopic follow-up is recommended following endoscopic ablation.15 Early detection of mucosal adenocarcinoma following ablation is crucial because it provides the opportunity to treat the lesion prior to the development of invasive cancer with the possibility of improving patient outcome. However, there are few studies regarding the incidence and risk of recurrent or metachronous adenocarcinoma following endoscopic ablation of BE.16, 17

The goals of this study were to estimate the risk of recurrence or the development of new adenocarcinoma following complete ablation therapy and to identify any predictive factors.

Patients and Methods

Study design

A retrospective analysis of patients with Barrett’s esophagus who underwent endoscopic ablation therapy in the Gastrointestinal Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital between 1996 and 2011 was performed. This study was approved by the hospital’s institutional review board. The primary endpoint of this study was the rate of recurrence or new development of esophageal cancer. Identification of predictors of adenocarcinoma following endoscopic ablation for BE was a secondary goal. Recurrence was defined as the presence of adenocarcinoma on endoscopic biopsy or EMR specimens following the absence of adenocarcinoma in biopsy samples from 2 consecutive surveillance endoscopies.17

Data collection

Data were obtained from a prospective database maintained in the Gastrointestinal Unit as well as the electronic and paper medical records. These data included demographic characteristics (age, gender, history of smoking, history of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use, body mass index (BMI)), endoscopic findings at first ablation (hiatal hernia and length of BE), most advanced histology prior to ablation, history of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) prior to 1st ablation, outcome after 1st ablation (calendar year of 1st ablation, stricture formation and histology), and date of recurrence/new development of adenocarcinoma.

Endoscopic treatment

Photodynamic therapy (PDT)

Porfimer sodium at a dose of 2mg/kg was administered intravenously on day 0, followed by 2 light exposures (day 2 and day4).18 Photoradiation was performed using a cylindric diffusing fiber at a wavelength of 630nm and a total energy of 150 J/cm.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA)

Circumferential RFA was performed using a HALO360 system (BÂRRX Medical, Inc, Sunnyvale, CA), with settings of 12J/cm2 and 300 watts. Additional RFAs for residual BE or focal BE were performed using a HALO90 device, with settings of 12J/cm2 and 40 watts.

Cryotherapy

Endoscopic spray cryotherapy was performed with the CSA cryotherapy system (CSA Medical, Baltimore, MD) that provided low-pressure liquid nitrogen with energy delivery of 25 Watts.

Fulguration

Multipolar coagulation was performed in some patients to treat residual areas of visible Barrett’s epithelium in patients with BE with/without low-grade dysplasia (LGD) to achieve eradication of all Barrett’s epithelium.

EMR

Beginning in 2000, small nodular areas of Barrett’s mucosa underwent EMR for diagnostic and/or therapeutic purposes. EMR was performed by using either a saline-assisted cap and snare technique or a band ligator device (Duette; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN).

All endoscopic procedures were performed over the study period by one of three experienced endoscopists, with the majority performed by one of the co-investigators (N.S.N.).

Follow-up evaluation

Patients were routinely placed on PPI therapy before and after ablation. A standardized surveillance protocol that was uniform across all prior histologies was used by endoscopists. Following ablation, endoscopies were performed every 2–3 months until biopsy specimens showed no residual intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia. After four consecutive exams showed the absence of residual BE, the endoscopic surveillance interval was extended to every 6 months. After four consecutive 6 month endoscopies were free of BE, the surveillance interval was extended to every 12 months. Histopathology of BE and BE-associated neoplasia was diagnosed by experienced gastrointestinal pathologists.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Univariate analysis was performed using a Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon ranksum test for continuous variables, and χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous or categorical variables. After univariate analyses, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of recurrence/new development of adenocarcinoma after ablation using the stepwise selection method. The following variables were examined: age at initial ablation, smoking history (presence or absence), history of PPI use (presence or absence), history of NSAID use (presence or absence), BMI at initial ablation (≤ 24.9, 25 – 29.9, 30≤), hiatal hernia size in cm (≤ 4, > 4), length of BE in cm (< 5, ≥ 5), histology after 1st ablation (no BE + BE + LGD, HGD + Adenocarcinoma). A time to recurrence analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meyer and log-rank test. The threshold for statistical significance was defined as two-sided P-value less than 0.05.

Results

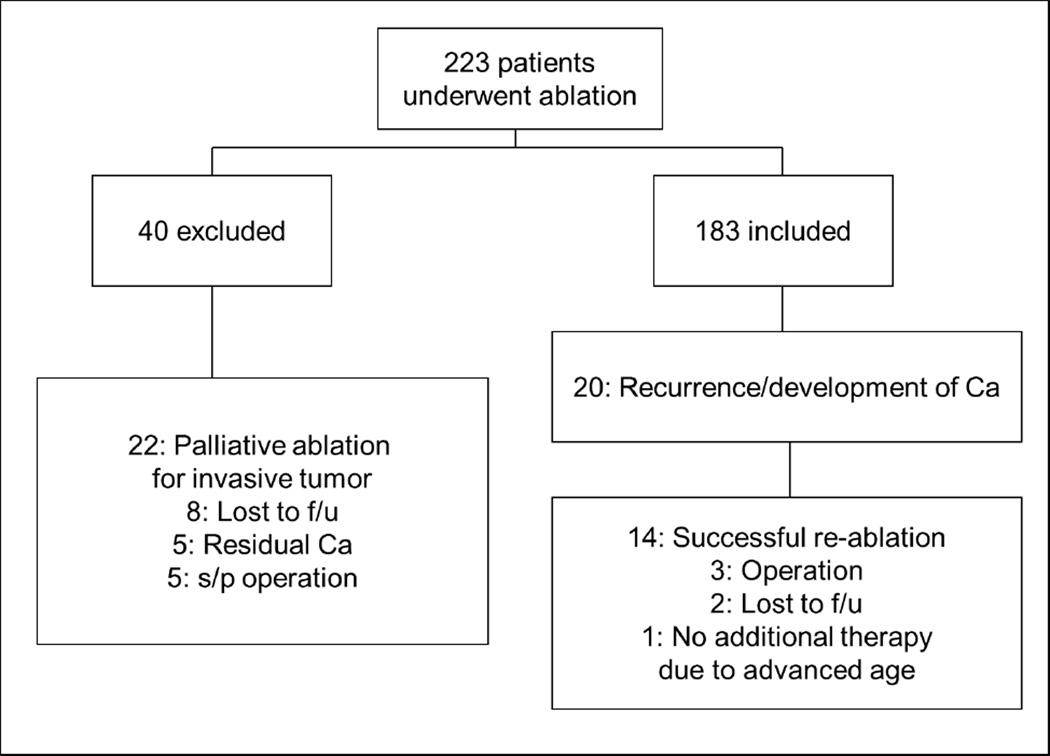

A total of 223 patients underwent ablation therapy for BE with HGD and/or adenocarcinoma between November, 1996 and July, 2011 (Fig. 1). Forty patients were excluded from the analysis: 22 for palliative ablation, 8 from lost to follow-up, 5 for residual carcinoma and 5 for postoperative state of esophagectomy. Among the 183 patients included in the study, the worst pre-treatment pathology was HGD in 103 patients and IMC in 80 patients. The median and mean follow-up were 39 and 47 months, respectively (range 5 – 179 months), and the median number of follow-up endoscopies per patient was 11 (range 2 – 40). The mean age of the patients was 68.8 years (Table 1). 79% of the patients were male, and 30% of the patients were obese (BMI ≥ 30).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients treated with ablation therapy for Barrett’s esophagus. Ca; carcinoma; f/u, follow-up; s/p, status post; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics and outcome after 1st ablation

| Characteristics | Total no. of patients (n = 183) |

Patients with rec/develp of adenoca (n = 20) |

Patients without rec/develp of adenoca (n = 163) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) at first abl | 0.09356 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 68.8 ± 10.9 | 72.7 ±11.7 | 68.3 ± 10.7 | |

| Range | 23 – 95 | 48 – 95 | 23 – 89 | |

| Gender | 0.2807 | |||

| Female | 38 (21%) | 6 (30%) | 32 (20%) | |

| Male | 145 (79%) | 14 (70%) | 131 (80%) | |

| History of smoking | 73 (45%) | |||

| (NA: 20) | 7 (35%) (NA: 1) | 66 (46%) (NA: 19) | 0.4588 | |

| History of NSAID use | 30 (17%) | |||

| (NA: 10) | 6 (30%)(NA: 1) | 24 (16%) (NA: 9) | 0.0823 | |

| History of PPI use | 164 (94%) (NA: 9) | 18 (90%) (NA: 1) | 146 (94%) (NA: 8) | 0.9235 |

| Body mass index | (NA: 36) | (NA: 1) | (NA: 35) | 0.1057 |

| ≤ 24.9 | 35 (24%) | 7 (37%) | 28 (22%) | |

| 25 – 29.9 | 68 (46%) | 10 (53%) | 58 (45%) | |

| 30 - | 44 (30%) | 2 (10%) | 42 (33%) | |

| Endoscopic findings at first abl | ||||

| Hiatal hernia at endoscopy | ||||

| Present | 99 (5 4%) | 16 (7 6%) | 83 (5 1%) | 0.0138 |

| > 4cm | 27 (15%) | 8 (38%) | 19 (12%) | 0.0007 |

| Length of BE ≥ 5cm | 118 (64%) | 15 (75%) | 103 (63%) | 0.2976 |

| Histology at first abl | 0.5483 | |||

| HGD | 103 (56%) | 10 (50%) | 93 (57%) | |

| Adenoca | 80 (44%) | 10 (50%) | 70 (43%) | |

| EMR performed before first abl | 117 (64%) | 1 (5%) | 116 (72%) | 0.0249 |

| Outcome after first abl | ||||

| Calendar year of 1st ablation | 0.046 | |||

| Median | 2005 | 2002 | 2005 | |

| Range | 1996 – 2011 | 1996 – 2009 | 1996 – 2011 | |

| Stricture | 24 (13%) | 5 (24%) | 19 (12%) | 0.3338 |

| Histology | 0.0012 | |||

| No BE | 41 | 3 | 38 | |

| BE | 66 | 3 | 63 | |

| LGD | 21 | 2 | 21 | |

| HGD | 44 | 7 | 35 | |

| Adenoca | 11 | 5 | 6 |

Abl, ablation; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; BE, Barrett's esophagus; LGD, low grade dysplasia; HGD, high grade dysplasia; adenoca, adenocarcinoma; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; rec, recurrence; develp, development; NA, not available.

During the study period, recurrence or new development of adenocarcinoma was observed in 20 patients (11%), of which 17 had IMC and 3 had invasive cancer requiring esophagectomy. Four of the 20 patients had a second recurrence after additional ablation therapy. 14 of the 17 patients with recurrent IMC successfully achieved remission with additional ablation, 2 were lost to follow-up and 1 had no additional therapy due to advanced age. Pathology on surveillance endoscopies following a second remission was: no BE in 3 patients, BE without dysplasia in 6, LGD in 1, and HGD in 4. The median time to recurrence/new development of adenocarcinoma following initial ablation for HGD or the ablation of achieving remission for IMC was 11.5 months (range 3 – 109 months). Both groups with and without recurrence of adenocarcinoma were treated with various combinations of ablation modalities (Table 2). The rate of recurrence for patients who received PDT as initial therapy and for those who received RFA is 12% (16/125) and 6% (3/46), respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between recurrence after a single ablation therapy (3/34, 9%) or after multiple ablation therapies (17/149, 11%.)

Table 2.

Type of ablation modality*

| Modality | Total Patients (n = 183) |

Adenocarcinoma Recurrence (n = 20) |

No Adenocarcinoma Recurrence (n = 163) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDT Only | 25 | 3 | 22 |

| PDT+ Other Ablation | 100 | 13 | 87 |

| RFA Only | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| RFA+ Other Ablation | 3 | 3 | 36 |

| Cryo Only | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Cryo+ Other Ablation | 10 | 1 | 9 |

Other ablation can include: PDT, photodynamic therapy; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; Cryo, cryoablation, ful, fulguration

In the univariate analysis, presence of hiatal hernia, hiatal hernia size greater than 4cm, and the histology (HGD/adenocarcinoma) after initial ablation were significantly associated with recurrence/development of adenocarcinoma after ablation. The calendar year of the initial ablation in patients with recurrence/development of adenocarcinoma was earlier than in patients without recurrence/development of adenocarcinoma. EMR performed before the initial ablation was less frequent in patients with recurrence/development of adenocarcinoma than in patients without recurrence/development of adenocarcinoma. In the multivariate analysis, the presence of hiatal hernia ≥ 4cm and histology (HGD/adenocarcinoma) following the initial ablation were significant predictors of recurrence or new development of adenocarcinoma after ablation (Table 3). The proportions of patients without recurrence/development, per subgroup of histology after initial ablation, are shown in Fig. 2. Recurrence-free period of patients with HGD or adenocarcinoma after initial ablation was significantly lower than that of patients with no BE or BE with/without LGD based on the log-rank test (P = 0.01).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of predictors of recurrence/development of adenocarcinoma after ablation

| Odd Ratio (CI 95%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Histology (HGD/adenoca) after 1st ablation | 4.141 (1.489 – 11.519) | 0.0065 |

| Hiatal hernia > 4cm | 3.649 (1.193 – 11.165) | 0.0233 |

HGD, high grade dysplasia; adenoca, adenocarcinoma.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients without recurrence/development of adenocarcinoma after ablation therapy according to the histology after 1st ablation. The time to recurrence in patients with Barrett’s esophagus (BE) with high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma after 1st ablation was significantly shorter than that in patients with no BE or BE with/without low-grade dysplasia (P = 0.01). No BE includes squamoglandular mucosa, no-specialized columnar mucosa and oxynto-cardiac mucosa.

Discussion

This cohort study based on a single-institution’s experience with a large series of patients who underwent endoscopic ablation of BE and HGD/IMC identified the incidence and predictors of recurrence or new development of adenocarcinoma following treatment. The cumulative rate of recurrence/development of adenocarcinoma was 11% (20 of 183 cases) during a median follow-up period of 39 months and the recurrence was associated with the presence of a large hiatal hernia and histology of HGD/adenocarcinoma following the first ablation. 14 of the 20 patients with a recurrence successfully achieved remission of adenocarcinoma with additional ablation.

Due to rapid innovations in endoscopic therapy, various ablation therapies have been developed and are now being used to treat patients with BE.19 However, only limited data are available regarding the risk of developing cancer following endoscopic ablation of BE. These data could serve to aid in optimizing surveillance and management strategies following ablation. In our study, the rate of metachronous adenocarcinoma during more than 3 years of follow-up was 11%. Several recent studies have shown varying rates of recurrence among patients treated with ablation. A study of 335 patients from the the UK National Halo Registry demonstrated a recurrence of invasive cancer in 10 (3%) after 12 months. 12 In a study of 54 BE patients who received RFA with endoscopic resection, Phoa et al reported a cancer recurrence of 6% after 5 years.13 Pech et al. reported outcomes in 349 BE patients (61 with HGD and 288 with IMC) who underwent endoscopic therapy with the median follow-up period of 63 months.20 The rate of metachronous lesions including HGD and adenocarcinoma was 21.5%. In a recent review of 65 articles for BE patients undergoing ablation, the weighted-average incidence rates were 1.58/1,000 patient-years (95% CI 0.66 – 3.84) for LGD and 16.76/1,000 patient-years (95% CI 10.6 – 22.9) for HGD patients.16 In addition, recurrence of esophageal intestinal metaplasia was demonstrated in 33% patients in a US Multicenter Consortium study. 14 Our results are comparable to these studies and demonstrate a need for further investigation into the rates of recurrence among patients treated with ablation.

In our study, a large hiatal hernia greater than 4 cm in length was a significant predictor of recurrence or metachronous adenocarcinoma following ablation of BE. Increasing evidence suggests that this anatomical and mechanical risk factor is related to the development of cancer. For example, studies have shown that the hiatal hernia was one of the most significant risk factors for Barrett’s progression to adenocaricnoma.21–23 Avidan et al. reported that a 5-cm hiatal hernia increased the risk by 2.53, as compared with the absence of hiatal hernia.21 A large cohort study with long-term follow-up by Weston et al. showed that the size of hiatal hernia was an independent risk factor for both diagnosis of either HGD/adenocarcinoma as well as progression of BE during surveillance.22 The larger the hiatal hernia, the greater the risk for clinically significant gastroesophageal reflux due to disruption of the antireflux barrier, which can lead to severe injury of the esophageal mucosa and may ultimately give rise to the cancer progression.24 The preventive effect of PPI treatment on neoplastic progression has been much studied and remains controversial.25, 26 However, some studies have demonstrated that the number of reflux episodes is an important risk factor for the subsequent development of adenocarcinoma in BE patients.21, 24, 27 The pathophysiologic mechanism of frequent reflux episodes due to large hiatal hernia may not be limited to healthy squamous epithelium but also to re-epithelialized neosquamous mucosa after ablation.

Of the 20 patients with recurrent adenocarcinoma, 16 received PDT as the initial therapy, 3 received RFA, and 1 received cryoablation. The number of cancer recurrences is too small to analyze using a multivariate logistic model. In addition PDT is the older technology/method and therefore has longer follow-up periods obfuscating the simple univariate finding of an increased recurrence rate.

The presence of HGD or adenocarcinoma following the initial ablation was also associated with an increased risk of recurrence or progression of adenocarcinoma after ablation, with the median time to recurrence following complete remission of 12 months. This finding makes intuitive sense as the persistence of HGD or adenocarcinoma could be an indicator or proxy of neoplasia that is either more technically difficult to treat or perhaps more biologically aggressive. However, there is also the possibility of a sampling error where these malignancies were already present in patients whose biopsy results were benign following the initial ablation. We believe that our frequent surveillance endoscopies with systemic biopsy protocol involving multiple biopsies of the neosquamous segment would have detected most cases of adenocarcinoma. A large prospective study with long-term follow-up of more than 5 years after endoscopic therapy for patients with HGD/IMC in BE demonstrated that metachronous neoplasia was strongly associated with longer periods needed to achieve complete remission.20 The neoplastic lesion in BE that is resistant to initial ablation therapy and requires additional treatments to achieve complete remission seems to have the high risk of recurrence. Such patients may warrant aggressive or heightened surveillance intervals and low risk candidates for surgery be offered the option of minimally invasive esophagectomy that can be performed safely in expert centers with very low morbidity and mortality rates. 27

Our study has several limitations. First, the study includes patients with HGD/adenocarcinoma that were treated by various combinations of endoscopic modalities, including PDT, RFA, cryotherapy, fulguration and EMR. However, the majority of patients had PDT as the alternative modality which has proven to have excellent long term effectiveness. Moreover, as various ablation modalities have been developed, many patients are treated with combinations of different modalities.19, 30 As a result, our data should provide valuable information to aid in the management of such patients. Second, the number of patients who had recurrent or newly developed adenocarcinoma after ablation during the follow-up period is relatively low, although statistical significance was achieved. Additional validation with a larger study in more than one center would be ideal.

In conclusion, our cohort study finds that the rate of long-term recurrent or metachronous adenocarcinoma after ablation is 11%, and large hiatal hernia and post 1st ablation histology are predictive of an increased risk of progression to adenocaricnoma. An intensive endoscopic surveillance regimen for BE patients with these risk factors could be beneficial detecting recurrent or newly developed adenocarcinoma at an early and endoscopically treatable stage. Moreover, the study raises some important questions in the future management of BE patients with HGD and/or IMC. Should the patients with HGD or IMC following the initial endoscopic treatment get referred for anti-reflux surgery to reduce the risk of acid exposure prior to further ablation therapies? Should minimally invasive esophagectomy be performed for the patients with large hiatal hernias at the time of confirming IMC? Is the combination of ablation therapy and EMR more effective in achieving durable ablation of BE than ablation therapy alone? Large, well-designed prospective studies are needed to solve these problems for improving the outcome of BE patients decreasing the risk of the progression to advanced esophageal cancer.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01CA140574 and U01CA152926 to C.H.).

References

- 1.Drewitz DJ, Sampliner RE, Garewal HS. The incidence of adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus: a prospective study of 170 patients followed 4.8 years. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:212–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaheen NJ, Crosby NA, Bozymski EM, et al. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastroenterology. 2000;119:587–589. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rastogi A, Puli S, El-Serag HB, et al. Incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s esophagus and high-grade dysplasia: meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:394–398. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Provenzale D, Schmitt C, Wong JB. Barrett’s esophagus: a new look at surveillance based on emerging estimates of cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2043–2053. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eloubeidi MA, Mason AC, Desmond RA, et al. Temporal trends (1973–1997) in survival of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma in the United States: a glimmer of hope? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1627–1633. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portale G, Peters JH, Hagen JA, et al. Comparison of the clinical and histological characteristics and survival of distal esophagealgastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma in patients with and without Barrett mucosa. Arch Surg. 2005;140:570–574. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.6.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overholt BF, Lightdale CJ, Wang KK, et al. Photodynamic therapy with porfimer sodium for ablation of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: international, partially blinded, randomized phase III trial. Gastrointestinal Endosc. 2005;62:488–498. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganz RA, Overholt BF, Sharma VK, et al. Circumferantial ablation of Barrett’s esophagus that contains high-grade dysplasia: a US multicenter registry. Gastrointestinal Endosc. 2008;68:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yachimski P, Puricelli WP, Nishioka NS. Patient predictors of histopathologic response after photodynamic therapy of Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia or intramucoal carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. New Engl J Med. 2009;360:2277–2288. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hur C, Choi SE, Rubenstein JH, et al. The cost effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2012 May 21; doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.010. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haidry RJ, Dunn JM, Butt MA, et al. Radiofrequency ablation and endoscopic mucosal resection for dysplastic barrett's esophagus and early esophageal adenocarcinoma: outcomes of the UK National Halo RFA Registry. Gastroenterology. 2013 Jul;145(1):87–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phoa KN, Pouw RE, van Vilsteren, et al. Remission of Barrett's Esophagus With Early Neoplasia 5 Years After Radiofrequency Ablation With Endoscopic Resection: A Netherlands Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2013 Jul;145(1):96–104. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta M, Iyer PG, Lutzke L, et al. Recurrence of esophageal intestinal metaplasia after endoscopic mucosal resection and radiofrequency ablation of Barrett's esophagus: results from a US Multicenter Consortium. Gastroenterology. 2013 Jul;145(1):79–86.2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1084–1091. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wani S, Puli SR, Shaheen NJ, et al. Esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus after endoscopic ablative therapy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:502–513. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badreddine RJ, Prasad GA, Wang KK, et al. Prevalence and predictors of recurrent neoplasia after ablation of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yachimsky P, Puricelli WP, Nishioka NS. Patient predictors of esophageal stricture development after photodynamic therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menon D, Stafinski T, Wu H, et al. Endoscopic treatments for Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review of safety and effectiveness compared to esophagectomy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pech O, Behrens A, May A, et al. Long-term results and risk factor analysis for recurrence after curative endoscopic therapy in 349 patients with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and mucosal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Gut. 2008;57:1200–1206. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.142539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, et al. Hiatal hernia size, Barrett’s length, and severity of acid reflux are all risk factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1930–1936. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weston AP, Sharma P, Mathur S, et al. Risk stratification of Barrett’s esophagus: updated prospective multivariate analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1657–1666. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weston AP, Badr AS, Hassanein RS. Prospective multivariate analysis of clinical, endoscopic, and histological factors predictive of the development of Barrett’s multifocal high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3413–3419. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, et al. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825–831. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillman LC, Chiragakis L, Shadbolt B, et al. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on markers of risk for high-grade dysplasia and oesophageal cancer in Barrett’s oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:321–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuipers EJ. Barrett’s oesophagus, proton inhibitors and gastric: the fog is clearing. Gut. 2010;59:148–149. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.191403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzgerald RC, Omary MB, Triadafilopoulos G. Dynamic effects of acid on Barrett’s esophagus: an ex vivo proliferation and differentiation model. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2120–2128. doi: 10.1172/JCI119018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Connell K, Velanovich V. Effects of Nissen fundoplication on endoscopic endoluminal radiofrequency ablation of Barrett’s esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:830–834. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Awais O, et al. Outcomes after minimally invasive esophagectomy: review of over 1000 patients. Ann Surg. 2012;256:95–103. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182590603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunki-Jacobs EM, Martin RC. Endoscopic therapy for Barrett’s esophagus: a review of its emerging role in optimal diagnosis and endoluminal therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1575–1582. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]