Abstract

Aim

As relationships between autistic traits, epilepsy, and cognitive functioning remain poorly understood, these associations were explored in the biologically related disorders tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), and epilepsy.

Method

The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), a quantitative measure of autistic traits, was distributed to caregivers or companions of patients with TSC, NF1, and childhood-onset epilepsy of unknown cause (EUC), and these results were compared with SRS data from individuals with idiopathic autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) and their unaffected siblings. Scores and trait profiles of autistic features were compared with cognitive outcomes, epilepsy variables, and genotype.

Results

A total of 180 SRS questionnaires were filled out in the TSC, NF1, and EUC outpatient clinics at the Massachusetts General Hospital (90 females, 90 males; mean age 21y, range 4–63y), and SRS data from 210 patients with ASD recruited from an autism research collaboration (167 males, 43 females; mean age 9y range 4–22y) and 130 unaffected siblings were available. Regression models showed a significant association between SRS scores and intelligence outcomes (p<0.001) and various seizure variables (p<0.02), but not with a specific underlying disorder or genotype. The level of autistic features was strongly associated with intelligence outcomes in patients with TSC and epilepsy (p<0.01); in patients with NF1 these relationships were weaker (p=0.25). For all study groups, autistic trait subdomains covaried with neurocognitive comorbidity, with endophenotypes similar to that of idiopathic autism.

Interpretation

Our data show that in TSC and childhood-onset epilepsy, the severity and phenotype of autistic features are inextricably linked with intelligence and epilepsy outcomes. Such relationships were weaker for individuals with NF1. Findings suggest that ASDs are not specific for these conditions.

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) are biologically related syndromes caused by mutations in the tumor-suppressor genes TSC1, TSC2, and NF1 respectively. Mutations in these and other genes, such as the fragile X mental retardation (FMR1) gene, can result in disruption of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway and are associated with cognitive impairment, epilepsy, and autistic features. Dysregulation of the mTOR pathway accounts for 10 to 15% of individuals with autism and may also represent a final common pathway for epilepsy and autism of unknown cause.1,2

Autism is a complex neurobehavioral disorder that includes impairments in social interaction, language and communication deficits, and stereotyped behaviors. Currently, autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are subclassified into autism, Asperger syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified.3 Autism associated with neurogenetic syndromes can be classified as ‘complex autism’, which is characterized by lower IQ and higher rates of epilepsy comorbidity.4 Because of the heterogeneous etiology but high heritability of ASDs, non-idiopathic disorders associated with autism seem attractive research models. However, although TSC and NF1 animal models display various neurocognitive features of these syndromes,5,6 autistic features have been difficult to reproduce. Clinical investigations of autistic features in TSC, NF1, and epilepsy have involved small or biased cohorts, dichotomous ASD outcomes, and lack of phenotypic characterization.7–10 Little is known about the relative contribution of the genetic risk factor to the autistic features and phenotype compared with the influence of cognitive impairment and epilepsy comorbidity. Increased understanding of the neurodevelopmental manifestations of these disorders will allow for more precise associations to be tested between biomarkers and specific traits, especially now that promising treatments are under study.11 In the current study, quantitative data on autistic features were compared with epilepsy and intelligence outcomes of large cohorts of patients with TSC, NF1, and childhood-onset epilepsy of unknown cause (EUC), and compared with the data from individuals with and without idiopathic ASDs.

METHOD

Patient recruitment

Individuals with TSC and NF1 were recruited at the outpatient clinics of the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Patients with non-familial, childhood-onset EUC with healthy brain imaging results were recruited at the outpatient adult and pediatric epilepsy clinics of MGH. Participants with sporadic, idiopathic ASD and their non-affected siblings were recruited through the Autism Consortium, a research and clinical collaboration that includes six Boston-area medical centers. Only Autism Consortium individuals who had been assigned a diagnosis of ASD based on both the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised12 and Autism Diagnostic Observational Schedule-Generic13 and for whom the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS)14 was available were included (see Fig. S1, online supporting information).

Assessment of autistic features

The SRS14,15 is a widely used, reliable and validated psychometric measure that assesses autistic traits in children of 4 years and older; an adult version is available for research purposes.16 The scale is completed by caregivers or companions and contains 65 items spanning five domains: (1) social awareness; (2) social cognition, including information processing and interpretation; (3) social and reciprocal communication; (4) social motivation, including questions on social anxiety and avoidance; and (5) autistic preoccupations and mannerisms such as stereotyped behavior. Raw scores are converted to sex-based T-scores; total T-scores greater than 60 are highly suggestive of any ASD, and scores greater than 75 are highly suggestive for autism.

Clinical information

Medical records were reviewed and the following information was recorded: age at evaluation, sex, history and types of seizures, age at seizure onset, refractory epilepsy (as defined by the International League Against Epilepsy17), number of antiepileptic drugs, and presence of a formal ASD diagnosis according to the DSM-IV3 criteria or Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised/Autism Diagnostic Observational Schedule-Generic evaluation.12,13 Full-scale IQs and developmental quotients (DQs) were assessed by various measures according to best practice standards. As full-scale IQ often does not completely reflect academic difficulties,18 and was not available for most patients with NF1, cognitive function was categorized as (1) no learning problems, (2) specific learning disability, or (3) global intellectual disability (IQ<70) including global developmental delay, as noted by the treating clinician.

As genetic mutation analysis is not a routine part of NF1 patient care, results of genetic mutation analysis were obtained for patients with TSC and categorized as TSC1 and TSC2 mutations, and NMI (no mutation identified). The mutation type was subgrouped into protein terminating (including nonsense, splice site, and frameshift mutations, and insertions and deletions ≥1 exon) and non-terminating (including missense mutations and small, in-frame insertions and deletions <1 exon) and the location of the mutation on the TSC2 gene was recorded. This study was approved by the institutional review board of MGH and by the Autism Consortium.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Within each study group, analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and correlations were performed to compare SRS scores with cognitive categories, epilepsy variables, age, and sex. For the TSC cohort, associations with mutation subgroups and a history of infantile spasms were also explored. A linear regression including all study groups was performed to assess the impact of a number of factors on SRS scores. Another linear regression model was constructed for the TSC cohort, to distinguish the effect of genetic background versus that of epilepsy and intelligence outcomes on the SRS scores. Finally, SRS subdomain scores were correlated with each other and with intelligence outcomes for each cohort. SRS t-scores were used for all analyses. All reported p-values used two-tailed tests of significance with alpha set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Outpatient clinics for participants with TSC, NF1, or epilepsy were scheduled on specific days, facilitating patient recruitment. The response rate was high and the included patient cohorts were representative, showing neurocognitive morbidity similar to previous observations and to non-responders (see Fig. S1 for patient inclusion and non-responder characteristics). In total, SRS data were collected for 180 patients at the MGH outpatient clinics (90 females,90 males; mean age 21y, range 4–63y) including 64 patients with TSC, 50 patients with NF1, and 66 individuals with EUC, henceforth called the ‘study groups’. The Autism Consortium database yielded SRS data on 210 Autism Consortium probands (167 males, 43 females; mean age 9y range 4–22y), henceforth called the ‘AC-ASD’ group, and 130 Autism Consortium unaffected siblings, henceforth called the ‘AC-siblings’. IQ/DQ scores were available for 45 (69%) patients with TSC, 42 (81%) patients with EUC, three (6%) patients with NF1, 118 (56%) patients in the AC-ASD group, and 68 (52%) AC-siblings (see Table I for clinical characteristics for all cohorts). The standardized and detailed documentation of the developmental and educational trajectory by experienced neurologists enabled the patient’s cognitive function category to be determined with a reasonably high degree of certainty. Information on epilepsy and developmental/educational trajectory was available for all study groups; however, information in the Autism Consortium database regarding the epilepsy type of probands and developmental history of siblings was incomplete.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of study and comparison groups

| Characteristic | TSC (n=64) | NF1 (n=50) | EUC (n=66) | AC-ASD (n=210) | AC comparison group (n=130) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male n (%) | 27 (42) | 31 (62) | 32 (48) | 167 (79) | 60 (46) |

| Female (%) | 37 (58) | 19 (38) | 34 (52) | 43 (21) | 71 (54) |

| Age at evaluation, y (range) | 22 (4–62) | 25 (4–63) | 16 (4–49) | 9 (4–22) | 10 (4–21) |

| Epilepsy n (%) | 53 (83) | 3 (6) | 100 | 15 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Mean age at onset, y (range) | 2.1 (0–21) | 2.0 (0–5) | 6 (0–17) | 3 (0–12) | – |

| Refractory n (%) | 26 (49) | 0 (0) | 25 (38) | 5 (42) | – |

| Mean nr of AEDs (range) | 1.5 (0–4) | 1 (0–1) | 1.6 (0–5) | 2 (1–5) | – |

| Seizure type (%) | |||||

| IS | 23 (36) | – | – | 3 (20) | – |

| Prim gen | – | 1 (33) | 34 (52) | 3 (20) | – |

| Absence | – | – | 8 (23) | 1 (33) | – |

| TC | – | – | 32 (60) | – | – |

| TC + absence | – | 1 (100) | 4 (11) | 2 (67) | – |

| Other | – | – | 2 (6) | – | – |

| Focal simple | 4 (8) | – | 4 (6) | – | – |

| Focal complex | 49 (92) | 2 (67) | 28 (42) | – | – |

| Unknown | – | – | – | 12 (80) | – |

| Mean IQ/DQ | 76 (15–134) | 101 (88–113a) | 80 (40–128) | 95 (34–148) | 111 (83–145) |

| Intellectual disability n (%) | 30 (47) | 3 (6) | 21 (32) | 40 (19) | 0 |

| Specific learning disability n (%) | 12 (19) | 23 (46) | 13 (20) | 103 (49) | n/a |

| ASD diagnosis | 15 (23) | 1 (2) | 10 (15) | 100 | 0 (0) |

| Autism | 15 (100) | – | 40 (44) | 188 (89) | – |

| Other ASD | – | 1(100) | 60 (56) | 22 (11%) | – |

| SRS | |||||

| Total score, mean (range) | 67 (36–95) | 60 (34–95) | 62 (35–95) | 81 (43–95) | 49 (34–95) |

| Social awareness | 59 (30–95) | 53 (30–77) | 54 (30–81) | 72 (36–95) | 45 (30–88) |

| Social cognition | 65 (36–95) | 60 (36–95) | 62 (36–95) | 79 (45–95) | 49 (36–95) |

| Social communication | 65 (37–95) | 58 (36–95) | 60 (37–95) | 79 (39–95) | 51 (37–95) |

| Social motivation | 64 (37–95) | 59 (37–95) | 61 (37–95) | 73 (37–95) | 51 (37–95) |

| Mannerisms | 69 (41–95) | 65 (40–95) | 64 (40–95) | 82 (42–95) | 50 (40–95) |

Numbers and percentages in subgroups are reflected as a fraction of the total of the subgroup.

Only three IQ scores were available for the NF1 cohort.

TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; NF1, neurofibromatosis type 1; EUC, childhood-onset epilepsy of unknown cause; AC, Autism Consortium; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; AED, antiepileptic drug; IS, infantile spasms; Prim gen, primary generalized; TC, tonic–clonic; DQ, developmental quotient; n/a, no information available; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale.

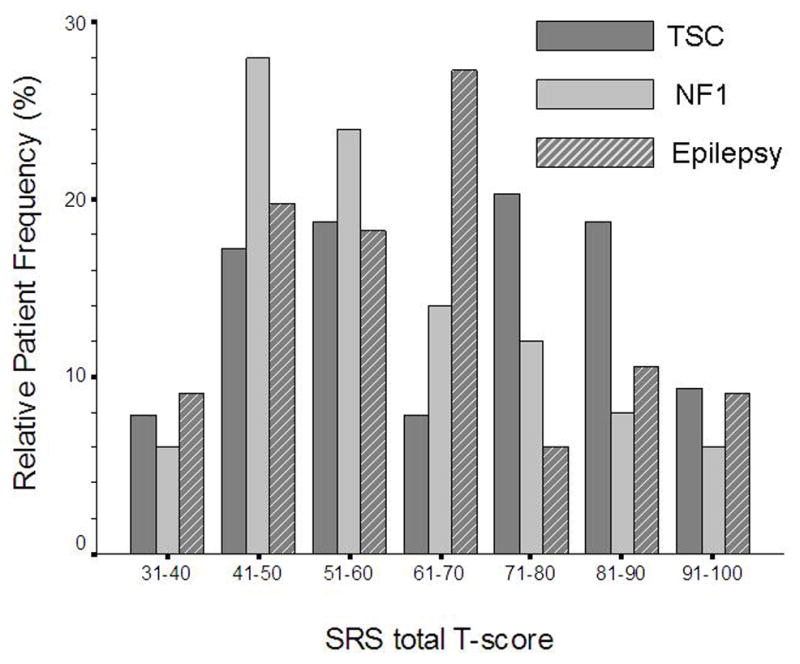

Distribution of autistic features

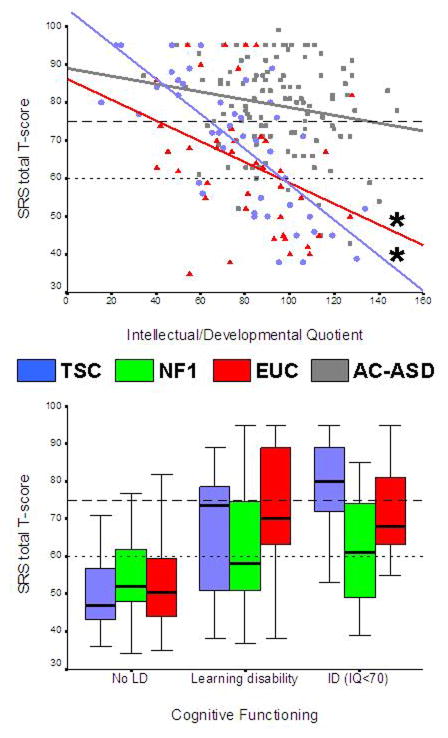

Although the NF1 and EUC groups showed normal distributions of autistic features, the TSC population displayed a bimodal distribution (Fig. 1). The numbers of patients with an SRS score higher than 60, which is suspect for ASD, was 36 (56%) in the TSC cohort, 20 (40%) in the NF1 cohort, and 35 (53%) in the EUC cohort. The prevalence of a score higher than 75, which is suspect for autism, was 24 (38%), 9 (18%), and 13 (20%) respectively. SRS total scores were not significantly associated with age (p>0.20 for all study groups) or sex (p>0.47 for all study groups).

Figure 1.

Histogram showing distribution of Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) scores for the relative frequencies of patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC, n=64), neurofibromatosis type 1 (n=50), and epilepsy (n=66). Note the bimodal distribution pattern in the TSC cohort. An SRS total score >75 indicates a high suspicion of autism, while a score between 60 and 75 is indicative of another autism spectrum disorder such as pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified.

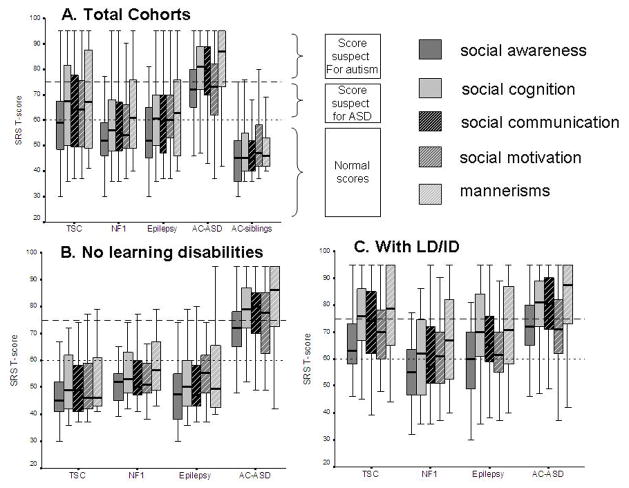

Association with neurocognitive phenotype

Results of ANOVAs and correlations are depicted in Table IIa. Highly significant inverse relationships between IQ/DQ and SRS total scores for TSC and EUC were observed (Fig. 2a), but these relationships were weaker in the NF1 cohort (Fig. 2b). The TSC cohort showed strong associations between SRS scores and all epilepsy variables, but these relationships were weaker in the EUC group. The mean SRS score of the four patients with NF1 with epilepsy was 11 points higher than that of patients without epilepsy, but owing to the small patient sample no statistical comparisons were performed.

Table II.

Results of statistical analysis

| (a) Bivariate associations between the SRS score and different variables per study group, depicting p-values for ANOVA’s and correlations

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| TSC SRS score (n=64) | NF1 SRS score (n=50) | EUC SRS score (n=66) | |

| ANOVAs | |||

| IQ categorya | <0.001 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Epilepsy | 0.001 | n/a | – |

| Refractory epilepsy | <0.001 | n/a | 0.40 |

| Infantile spasms | 0.018 | n/a | n/a |

| Correlations | |||

| IQ/DQ score | 0.001 (r=−0.74) | n/a | 0.016 (r=−0.37) |

| Age at onset of epilepsy | 0.035 (r=−0.33) | n/a | 0.24 (r=−0.15) |

| (b) Variables in the linear regression models, including the total Social Responsiveness Scale score as the dependent outcome

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Ba | p | 95% CI of Bb

|

|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Multidisorder model (n=180) R2=0.37 | ||||

| Study group | ||||

| TSC | 17.3 | 0.31 | −8.6 | 2.8 |

| EUC | 23.7 | 0.14 | −7.5 | 54.9 |

| NF1 | 0c | – | – | – |

| IQ category | ||||

| Normal learning | −16.8 | 0.001 | −26.7 | −6.9 |

| Learning disability | 0c | – | – | – |

| Intellectual disability | 30.1 | 0.079 | −3.6 | 65.6 |

| Epilepsy | 10.8 | 0.613 | −31.6 | 53.2 |

| Refractory epilepsy | 2.0 | 0.19 | −1.03 | 5.0 |

| Age at epilepsy onset | −0.28 | 0.40 | −0.9 | 0.38 |

| TSC-specific model (n=45) R2=0.66 | ||||

| Mutation type | ||||

| TSC1 | −0.12 | 0.99 | −18.7 | 18.4 |

| TSC2 | −6.4 | 0.45 | −23.2 | 10.5 |

| NMI | −4.2 | 0.70 | −25.9 | 17.3 |

| Unknown | 0c | – | – | – |

| IQ/DQ | −0.27 | 0.015 | −0.49 | −0.06 |

| Epilepsy | 20.7 | 0.023 | 3.0 | 38.4 |

| Refractory epilepsy | 15.7 | 0.008 | 4.3 | 27.0 |

| Infantile spasms | 6.3 | 0.196 | −3.4 | 15.9 |

Complete clinical data were available for all patients and IQ/DQ scores were available for 45 patients with TSC, 42 (81%) patients with EUC, and three (6%) patients with NF1. n, number of patients included in the analysis; r, correlation coefficient.

No learning problems, specific learning disability, or global intellectual disability (see Methods section).

TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; NF1, neurofibromatosis type 1; EUC, childhood-onset epilepsy of unknown cause; ANOVA, analysis of variance; n/a, not analyzed owing to small patient samples or insufficient data; DQ, developmental quotient.

The coefficient of that variable in the overall model.

95% confidence intervals surrounding the B.

This group was designated as the reference category.

n, number of patients included in the analysis; CI, confidence interval; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; EUC, childhood-onset epilepsy of unknown cause; NF1, neurofibromatosis type 1; NMI, no mutation identified; DQ, developmental quotient.

Figure 2.

Graphs showing the relationship between cognitive outcomes and level of autistic features. (a) Scatterplot of IQ/DQ outcomes and Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) scores for the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC, n=45), epilepsy (n=42), and idiopathic autism spectrum disorder (AC-ASD) (n=118) cohorts.*p<0.05. (b) Boxplots showing SRS total scores per cognitive category for all individuals with TSC (n=64), neurofibromatosis type 1 (n=50), and epilepsy (n=66).

(Typesetter change A B labels to lower case]

Association with TSC genotype

Although the TSC2 mutation subgroup showed higher SRS scores than the TSC1 and NMI groups, the difference was not significantly different (p=0.02). The mean SRS score of the four patients with TSC2 missense mutations was 10 points lower than mean score of the 17 individuals with TSC2 protein-terminating mutations.

Results of linear regression analysis

The regression model with all patients with TSC, NF1, and EUC, included five independent variables, chosen from their statistical significance on bivariate analyses. Cognitive category and various epilepsy variables were significant predictors of SRS scores, but no significant association with the underlying disorder was found (Table IIb).

A similar regression model was constructed for the patients with TSC for whom IQ/DQ data were available, showing that a history of epilepsy, refractory epilepsy, and intelligence outcomes were all highly associated with SRS scores, but TSC mutation subgroups or a history of infantile spasms were not significant predictors (Table IIb).

Phenotype

Within each study group, the SRS subdomain scores (social awareness, social cognition, social communication, social motivation, and mannerisms) correlated strongly with each other (r>0.40, p<0.005 for all groups). The study groups and AC-ASD group showed similar trait profiles on the SRS, with relatively higher scores for the social cognition and mannerisms domains and less affected social awareness domains (Fig. 3a). This profile was attenuated for individuals without specific learning disability or intellectual disability (Fig. 3b) or without epilepsy, all of whom showed mean domain scores in the normal ranges, although patients with NF1 without learning disability showed relatively high scores on the mannerism domain. For individuals with specific learning disability or intellectual disability, this trait profile became more pronounced (Fig. 3c). Finally, to approximate a true autistic phenotype, individuals with SRS T-scores greater than 60 were selected and more striking trait differences were observed; study groups showed relatively less affected social awareness and relatively more mannerisms, although the profiles remained similar to those of the AC-ASD cohort. In general, the social communication domain seemed consistently average of the other traits, regardless of the neurocognitive profile.

Figure 3.

Boxplots depicting Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) trait profiles for selected study cohorts. Each box shows the median and quartiles within a category. Reference lines indicate thresholds above which T-scores are clinically suspect for autism (>75, striped line) or other autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) (60–75, dotted line). (a) SRS scores for all cohorts, including patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC, n=64), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1, n=50), epilepsy (n=66), idiopathic ASD (n=210), and sibling comparison group (n=130). (b) SRS trait scores for individuals without intellectual disability or learning disability, with TSC (n=22), NF1 (n=22), epilepsy (n=32), and idiopathic ASD (n=67). (c) SRS trait scores for individuals with a specific learning disability or intellectual disability (LD/ID) with TSC (n=42), NF1 (n=27), epilepsy (n=34), and idiopathic ASD (n=142).

[Typesetter: change ABC labels to lower case: move title of each graph to bottom of graph]

The TSC cohort showed strong correlations between autistic trait domains and IQ/DQs on all domains, whereas this relationship was weaker for the EUC and AC-ASD cohorts and absent in the AC-sibling group (Table III). For the EUC and AC-ASD cohorts, lower intelligence outcomes were generally associated with more impaired social cognition, social communication, and mannerisms but less associated with social awareness and social motivation domains. In the TSC2 cohort, the social cognition domain was relatively impaired, while for the TSC1 and NMI groups the social motivation domain was more severely affected, similar to the EUC groups without learning disabilities.

Table III.

Correlations between intelligence outcomes and SRS subdomain scores for study groups

| Study group | Social awareness | Social cognition | Social communication | Social motivation | Mannerisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSC IQ/DQ (n=45) | −0.85a | −0.92a | −0.96a | −0.85a | −0.91a |

| Epilepsy IQ/DQ (n=42) | −0.24 | −0.42b | −0.35b | −0.22 | −0.43b |

| AC-ASD IQ/DQ (n=118) | −0.10 | −0.30a | −0.15 | −0.11 | −0.11 |

| AC-sibling IQ/DQ (n=68) | −0.06 | −0.16 | −0.20 | −0.20 | −0.18 |

The group with neurofibromatosis type 1 is not included owing to the lack of IQ scores. n, number of patients for whom quantitative IQ/DQ scores were available.

Significant to p<0.001 level;

Significant to p<0.05 level.

SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; DQ, developmental quotient; AC, Autism Consortium; ASD, autism spectrum disorder.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to compare quantitative scores on autistic features and traits in large cohorts of biologically related disorders. Similar mechanistic and phenotypic relationships were apparent, suggesting that autistic features covary strongly with neurocognitive comorbidity, rather than with the specific underlying disorder.

Relationships with cognitive outcomes

Patients with TSC and EUC showed highly significant inverse associations between IQ and total SRS score, implying that autistic features are not specific in these disorders, but are part of the same neurocognitive construct. In other words, the more severe and global the cognitive impairment, the more likely it is that the responsible underlying brain dysfunction also affects the widely distributed networks responsible for social behavior, language, and cognitive flexibility. These relationships seemed less robust in patients with idiopathic ASD and those with NF1, probably due to less variability in SRS scores and cognitive outcomes respectively.

These findings expose an important reason for diagnostic disagreement for ASD in patients with neurodevelopmental disorders. The diagnosis of autism requires that autistic features cannot be fully explained by developmental delays.19,20 Hence, only those autistic behaviors which cannot be explained by the level of cognitive functioning should be recorded and categorized as autistic ‘features’ or ‘traits’. The term ‘complex’ or ‘syndromal’ autism should be reserved for autistic symptoms across all core domains of the DSM-IV criteria.

Relationship with epilepsy

Although the relationship between epilepsy and autism has been recognized since the description of the first patients with autism,21 the underlying mechanism is still unclear.19 In patients with TSC, significant associations were found between SRS scores and refractory epilepsy, early onset of seizures, and a relatively severe seizure type such as infantile spasms; however, such relationships were not significant in the EUC cohort, confirming previous observations in individuals with borderline to normal intelligence.22,23 Interestingly, the TSC-specific regression analysis highlighted refractory epilepsy as the most important predictor of higher SRS scores, emphasizing that not all patients with infantile spasms experience adverse neurocognitive outcomes, but specifically those with any type of poorly controlled seizures.24 These observations confirm a global phenomenon that, regardless of the underlying disorder, children who have a history of severe or refractory epilepsy at an early age represent a subgroup associated with insults to the developing brain manifesting in a more severe cognitive and autistic phenotype.25–27 Furthermore, these findings support a previous suggestion that patients with epilepsy and ASD should be included in the subgroup of complex autism.23

Unfortunately, our design does not allow us to explore whether the autistic features and cognitive impairments are caused by epilepsy, or whether these are all the result of the same underlying brain dysfunction.19 Although seizures may cause cognitive deficits by disturbing neuronal patterning and myelination, there is increasing evidence that synaptic protein imbalances are responsible for neurocognitive morbidity in mTOR-related syndromes.1,28 Treatment or prevention of these synaptic imbalances and early life epilepsy may also reverse or prevent cognitive impairments and autistic features.29

Relationship with genetic background

It is well recognized that the prevalence of autistic features is much higher in TSC than in NF1 (25–60% and 0–4% respectively), and TSC2 versus other mutations.1,8 Although there are some indications for genotype–neurocognitive phenotype relationships in TSC and NF1,30–32 direct links between autism and specific TSC or NF1 gene loci have not been identified.33 We are the first to show that, in TSC, the level of autistic features follows a similar pattern as intelligence outcomes, showing a bimodal distribution, higher SRS scores in the TSC2 mutation subgroup,8 and the suggestion of a milder autistic phenotype in patients with TSC2 missense mutations.30 Regardless of these associations, regression models could not distinguish a unique effect of any underlying disorder or genetic mutation on the SRS scores. Additionally, patients with TSC without learning disabilities or epilepsy showed normal SRS scores, suggesting that TSC germline mutations do not exert a uniform effect on autistic features. These observations, together with the weak predictive strength of the multidisorder regression model, confirm that in TSC, and perhaps other neurogenetic syndromes such as NF1, it is unlikely that heterozygous mutations alone can cause brain disruption, and additional genetic, epigenetic, or environmental factors are necessary to produce the neurocognitive phenotype.34,35

Autistic trait profiles

A key question in investigating autistic phenotypes is whether the symptom clusters, such as social skills and repetitive behaviors, are independent or covary. Our observations suggest that in TSC, NF1, and EUC, autistic traits covary together and are strongly dependent on neurocognitive comorbidity. The trait profiles of patients with NF1, TSC, and childhood-onset epilepsy were similar to each other and to individuals with idiopathic ASD. In general, there was a trend for more severely impaired social cognition and mannerisms with relative preservation of social awareness, reminiscent of autistic traits described in patients with fragile X syndrome. The mannerisms subdomain was most consistently affected for all study groups with cognitive impairments, possibly reflecting the subgroup of mannerisms whereby the sensory and motor repetitive behaviors are generally associated with lower IQs.36 The social motivation domain was relatively more affected within the typical-learning EUC population and the TSC1 and NMI subgroups, resembling the social alienation and interpersonal sensitivity that has previously been reported in healthy and mildly affected individuals with TSC, epilepsy, fragile X syndrome, and patients with idiopathic ASD.37–39

Altogether, the interdisorder similarities and intrasyndrome phenotypic heterogeneity suggest there is no mTOR-specific autistic phenotype. Hence, the debate in fragile X syndrome whether these autistic-like behaviors truly represent autism or are a ‘phenocopy’ of autism,34 seems irrelevant.

Limitations

It is noteworthy that the SRS was not used as a diagnostic instrument but as a tool to explore quantitative relationships. Incongruities such as the overall higher than expected level of autistic features and mannerisms in patients with NF1 suggest that the SRS may not be specific for autistic features in NF1 and may be confounded by other psychiatric disorders that are known to be frequent in NF1. Future studies should validate the SRS in all of these disorders. Secondly, as disruption of the mTOR pathway has been implicated in idiopathic cases of epilepsy and autism, our observations on phenotypic profiles may not reflect distinctly biologically different neurodevelopmental disorders. Thirdly, as a group, siblings of individuals with autism have been shown to have a higher rate of (subclinical) autistic features40 and do not represent the typically developing population. However, for our purposes the AC-siblings were a suitable comparison group, as they were all clinically evaluated for autistic features, familial ASDs were excluded, and their SRS scores were very similar to a typically developing population. Furthermore, we did not investigate relationships between autistic features and seizure frequency or specific anticonvulsants, which may impair neurocognition,41 and future studies should explore this. Finally, in the case of both Autism Consortium cohorts, the age at evaluation was lower than in the study groups; although in idiopathic ASD, autistic symptoms may decrease over time, there is no information on how this would affect the phenotype.

CONCLUSIONS

Our observations suggest that the autistic features in TSC, NF1, and childhood-onset epilepsy are an inextricable part of neurocognition, covarying with intelligence and epilepsy variables. These findings confirm similar findings in other syndromes,25,42–44 and raise the question of whether ASD is a specific condition in any disorder associated with cognitive impairment. Future research should focus on the determinants of the variability of neurocognitive phenotypes in these disorders, exploring relationships between genetic events, synaptic function, and neuroanatomical manifestations.45,46 Mouse models and clinical studies elucidating one component of the epilepsy–intelligence–autism triad may inherently explain the pathophysiology of the others. Findings in mTOR-related disorders may elucidate the pathophysiology of ‘complex autism’ and perhaps idiopathic ASD in general.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

Autistic features are an inextricable part of neurocognition in TSC and epilepsy.

The level of autistic features was better predicted by neurocognitive comorbidity than by the underlying disorder or mutation.

The autistic phenotype covaried with neurocognitive morbidity.

There was no evidence for a disorder-specific autistic endophenotype.

Autism spectrum disorder is not a specific disorder in TSC, NF1, and epilepsy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the families and individuals who agreed to participate in this study and the Autism Consortium for their valuable time and effort. We are grateful to the Autism Consortium for access to the data analyzed here, and for the support from Christine Ferrone and Roksana Sasanfar for assisting with the Autism Consortium data collection. We thank Zaida Ortega, Christina Anagnos, Jill Beamon, and Joseph Nimon for assisting with distribution and scoring of the questionnaires. Lastly, we are grateful to the MGH Department of Biostatistics for assistance with statistical analysis. This study was sponsored by the Herscot Center for Tuberous Sclerosis Complex, and NIH/NINDS P01 NS024279.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ASD

Autism spectrum disorder

- EUC

Childhood-onset epilepsy of unknown cause

- MGH

Massachusetts General Hospital

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- NF1

Neurofibromatosis type 1

- NMI

No mutation identified

- SRS

Social Responsiveness Scale

- TSC

Tuberous sclerosis complex

Footnotes

The following additional material may be found online.

Figure S1: Flowchart depicting derivation of analyzed study cohorts. MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; NF1, neurofibromatosis type 1; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ADOS Autism Diagnostic Observational Schedule; ADI-R, Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; AC, Autism Consortium.

Please note: This journal provides supporting online information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but may not be copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues or other queries (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

References

- 1.Kelleher RJ, 3rd, Bear MF. The autistic neuron: troubled translation? Cell. 2008;135:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDaniel SS, Wong M. Therapeutic role of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition in preventing epileptogenesis. Neurosci Lett. 2011;3:231–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miles JH, Takahashi TN, Bagby S, et al. Essential versus complex autism: definition of fundamental prognostic subtypes. Am J Med Genet A. 2000;135:171–80. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goto J, Talos DM, Klein P, et al. Regulable neural progenitor-specific Tsc1 loss yields giant cells with organellar dysfunction in a model of tuberous sclerosis complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E1070–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106454108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui Y, Costa RM, Murphy GG, et al. Neurofibromin regulation of ERK signaling modulates GABA release and learning. Cell. 2008;135:549–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutierrez GC, Smalley SL, Tanguay PE. Autism in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Autism Dev Disord. 1998;28:97–103. doi: 10.1023/a:1026032413811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Numis AL, Major P, Montenegro MA, Muzykewicz DA, Pulsifer MB, Thiele EA. Identification of risk factors for autism spectrum disorders in tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurology. 2011;76:981–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182104347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg AT, Plioplys S, Tuchman R. Risk and correlates of autism spectrum disorder in children with epilepsy: a community-based study. J Child Neurol. 2001;26:540–7. doi: 10.1177/0883073810384869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fombonne E, Du Mazaubrun C, Cans C, Grandjean H. Autism and associated medical disorders in a French epidemiological survey. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psych. 1997;36:1561–9. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehninger D, Silva AJ. Genetics and neuropsychiatric disorders: treatment during adulthood. Nat Med. 2009;15:849–50. doi: 10.1038/nm0809-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:659–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, et al. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30:205–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Constantino JN, Gruber CP. Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) Los Angeles CA: Western Psychological Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granader YE, Bender HA, Zemon V, Rathi S, Nass R, Macallister WS. The clinical utility of the Social Responsiveness Scale and Social Communication Questionnaire in tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;18:262–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Constantino JN, Todd RD. Intergenerational transmission of subthreshold autistic traits in the general population. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:655–60. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1069–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berg AT, Hesdorffer DC, Zelko FA. Special education participation in children with epilepsy: what does it reflect? Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berg AT, Plioplys S. Epilepsy and autism: is there a special relationship? Epilepsy Behav. 2012;23:193–5. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sevin JA, Bowers-Stephens C, Crafton CG. Psychiatric disorders in adolescents with developmental disabilities: longitudinal data on diagnostic disagreement in 150 clients. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2003;34:147–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1027346108645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child. 1943;2:217–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Constantino JN, Przybeck T, Friesen D, Todd RD. Reciprocal social behavior in children with and without pervasive developmental disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000;21:2–11. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200002000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amiet C, Gourfinkel-An I, Bouzamondo A, et al. Epilepsy in autism is associated with intellectual disability and gender: evidence from a meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:577–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goh S, Kwiatkowski DJ, Dorer DJ, Thiele EA. Infantile spasms and intellectual outcomes in children with tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurology. 2005;65:235–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000168908.78118.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Nonell C, Ratera ER, Harris S, et al. Secondary medical diagnosis in fragile X syndrome with and without autism spectrum disorder. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:1911–16. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisermann MM, DeLaRaillere A, Dellatolas G, et al. Infantile spasms in Down syndrome – effects of delayed anticonvulsive treatment. Epilepsy Res. 2003;55:21–7. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(03)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cormack F, Cross JH, Isaacs E, et al. The development of intellectual abilities in pediatric temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48:201–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Auerbach BD, Osterweil EK, Bear MF. Mutations causing syndromic autism define an axis of synaptic pathophysiology. Nature. 2011;480:63–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talos DM, Sun H, Zhou X, et al. The interaction between early life epilepsy and autistic-like behavioral consequences: a role for the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. PloS One. 2012;7:e35885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Eeghen A, Black M, Pulsifer M, Kwiatkowski D, Thiele E. Genotype and cognitive phenotype in patients with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:510–15. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Descheemaeker MJ, Roelandts K, De Raedt T, Brems H, Fryns JP, Legius E. Intelligence in individuals with a neurofibromatosis type 1 microdeletion. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;131:325–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mautner VF, Kluwe L, Friedrich RE, et al. Clinical characterisation of 29 neurofibromatosis type-1 patients with molecularly ascertained 1. 4 Mb type-1 NF1 deletions. J Med Genet. 2010;47:623–30. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.075937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plank SM, Copeland-Yates SA, Sossey-Alaoui K, et al. Lack of association of the (AAAT)6 allele of the GXAlu tetranucleotide repeat in intron 27b of the NF1 gene with autism. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:404–5. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leblond CS, Heinrich J, Delorme R, et al. Genetic and functional analyses of SHANK2 mutations suggest a multiple hit model of autism spectrum disorders. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin W, Chan JA, Vinters HV, et al. Analysis of TSC cortical tubers by deep sequencing of TSC1, TSC2 and KRAS demonstrates that small second-hit mutations in these genes are rare events. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:1096–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carcani-Rathwell I, Rabe-Hasketh S, Santosh PJ. Repetitive and stereotyped behaviours in pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:573–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pulsifer MB, Winterkorn EB, Thiele EA. Psychological profile of adults with tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10:402–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson MJ, Turkington D. Depression and anxiety in epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:45–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.060467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hagerman RJ. Lessons from fragile X regarding neurobiology, autism, and neurodegeneration. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27:63–74. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200602000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Constantino JN, Zhang Y, Frazier T, Abbacchi AM, Law P. Sibling recurrence and the genetic epidemiology of autism. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1349–56. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hermann B, Meador KJ, Gaillard WD, Cramer JA. Cognition across the lifespan: antiepileptic drugs, epilepsy, or both? Epilepsy Behav. 2010;17:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rasmussen P, Borjesson O, Wentz E, Gillberg C. Autistic disorders in Down syndrome: background factors and clinical correlates. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:750–4. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201001372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Molloy CA, Murray DS, Kinsman A, et al. Differences in the clinical presentation of Trisomy 21 with and without autism. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2009;53:143–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trillingsgaard A, Ostergaard JR. Autism in Angelman syndrome: an exploration of comorbidity. Autism. 2004;8:163–74. doi: 10.1177/1362361304042720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Payne JM, Moharir MD, Webster R, North KN. Brain structure and function in neurofibromatosis type 1: current concepts and future directions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:304–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.179630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ridler K, Suckling J, Higgins NJ, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of memory deficits in tuberous sclerosis complex. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:261–71. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.