Abstract

Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a clinically important pathogen that causes opportunistic infections and nosocomial outbreaks. Recently, the type III secretion system (TTSS) has been shown to play an important role in the virulence of P. aeruginosa. ExoU, in particular, has the greatest impact on disease severity. We examined the relationship among the TTSS effector genotype (exoS and exoU), fluoroquinolone resistance, and target site mutations in 66 carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains.

Methods

Sixty-six carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains were collected from patients in a university hospital in Daejeon, Korea, from January 2008 to May 2012. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin) were determined by using the agar dilution method. We used PCR and sequencing to determine the TTSS effector genotype and quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) of the respective target genes gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE.

Results

A higher proportion of exoU+ strains were fluoroquinolone-resistant than exoS+ strains (93.2%, 41/44 vs. 45.0%, 9/20; P≤0.0001). Additionally, exoU+ strains were more likely to carry combined mutations than exoS+ strains (97.6%, 40/41 vs. 70%, 7/10; P=0.021), and MIC increased as the number of active mutations increased.

Conclusions

The recent overuse of fluoroquinolone has led to both increased resistance and enhanced virulence of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa. These data indicate a specific relationship among exoU genotype, fluoroquinolone resistance, and resistance-conferring mutations.

Keywords: TTSS effector genotype, exoS, exoU, Fluoroquinolone resistance

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen that can cause a wide spectrum of acute infections in hospitalized and immunocompromised patients as well as chronic lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. The pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa is the result of numerous secreted virulence factors. Among the multitude of virulence determinants of Pseudomonas, the type III secretion system (TTSS) is considered an important contributor to the cytotoxicity and the invasion process [1, 2, 3]. This system allows these bacteria to directly inject effector proteins into the host cell, where they subvert host cell defense and signaling systems [4]. Four effector proteins have been identified: ExoU, a phospholipase; ExoY, an adenylate cyclase; and ExoS and ExoT, which are bifunctional proteins. ExoT and ExoY are encoded by almost all strains, though not all strains produce functional ExoY because of the presence of frameshift mutations. ExoS and ExoU are variably encoded genes depending on the disease site or background. In particular, ExoT and ExoY have a minor effect on virulence, whereas ExoS and ExoU contribute greatly to the pathogenesis [5, 6, 7, 8]. In a mouse model of acute pneumonia, secretion of ExoU has the greatest impact on mortality, bacterial persistence, and dissemination in the lungs, followed by secretion of ExoS and ExoT [1, 9, 10, 11].

In recent years, the incidence of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains has increased worldwide. The fluoroquinolone antimicrobials are the most potent agents for treatment of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa infections. Nonetheless, a number of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains have exhibited increased resistance to fluoroquinolone, and these strains have emerged rapidly in South Korea [12, 13, 14, 15]. According to the study by Lee et al. [16], 57 carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains isolated in 10 South Korean hospitals showed strong resistance to ciprofloxacin (59.6%). On the other hand, there are few studies on the resistance to fluoroquinolones and on the prevalence of alterations in topoisomerase II and IV in carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains collected in South Korea.

Alterations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) within topoisomerase II (GyrA and GyrB subunits) and topoisomerase IV (ParC and ParE subunits) are the major contributors to fluoroquinolone resistance in gram-negative bacteria [17, 18]. In particular, amino acid alterations in the GyrA and ParC subunits play a major role in conferring strong fluoroquinolone resistance to gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter baumannii, and P. aeruginosa [19, 20, 21].

The aim of this study was to assess a possible correlation between the TTSS effector genotype (exoS vs. exoU) and fluoroquinolone resistance in carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains. In addition, we compared the prevalence and degree of fluoroquinolone resistance with respect to the alterations in topoisomerases II and IV.

METHODS

1. Isolation and identification of bacteria

In total, 66 consecutive and nonduplicated carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains were obtained from patients in a university hospital in Daejeon, Korea, from January 2008 to May 2012. The strains were identified with the Vitek 2 automated ID system (BioMérieux, Hazelwood, MO, USA), and carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains were selected on the basis of resistance to imipenem and meropenem.

2. Testing of susceptibility to antimicrobials

Using the agar dilution method and CLSI guidelines, antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed by determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) [22]. The susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to the following antimicrobial agents was tested: ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). The interpretation of susceptibility was performed according to the CLSI breakpoints. E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used as quality controls.

3. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST)

MLST was carried out according to the methods described on the website of the P. aeruginosa MLST database (http://pubmlst.org/paeruginosa/). Genomic DNA was extracted from the clinical strains by using the Genomic DNA Prep Kit (SolGent, Daejeon, Korea). PCR was performed by using 50 ng of template DNA (genomic DNA) using 2.5 µL 10× Taq buffer, 0.5 µL of 10 mM dNTP mix, 20 pmol of each primer, and 0.7 U Taq DNA polymerase (SolGent) in a total volume of 25 µL. Internal fragments of 7 housekeeping genes (acsA, aroE, guaA, mutL, nuoD, ppsA, and trpE) were amplified by using a GeneAmp PCR System 9600 (Perkin-Elmer Cetus Corp., Norwalk, CT, USA). The reaction mixture was denatured for 1 min at 96℃, and then subjected to 30 cycles of 1 min at 96℃, 1 min at 55℃, and 1 min at 72℃, with a final elongation step at 72℃ for 10 min. The amplicons were purified by using a PCR purification kit (SolGent) and were then sequenced by using a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and an ABI PRISM 3730XL DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The nucleotide sequences of each of the 7 housekeeping genes were compared with the sequences stored in the MLST database to determine the allelic numbers and sequence types (STs).

4. Analysis of TTSS effector genotypes (exoS and exoU) and sequencing of target site mutations

To detect the TTSS effector genotype (exoS and exoU) and the QRDRs of the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes, genomic DNA of all carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains was amplified by means of PCR as described previously [23, 24]. The resulting DNA sequences were compared with published nucleotide sequences from the GenBank database (Accession numbers: L29417 [gyrA], AE004440 [gyrB], AB003428 [parC], and AB003429 [parE]) by using the BLAST search available on the website of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, MD, USA).

5. Statistical analysis

All 66 strains were grouped into specific TTSS effector genotypes on the basis of their degree of resistance to fluoroquinolones, as indicated by MIC and by the number and type of target site mutations. Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests were used where appropriate. A difference with a P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. TTSS effector genotypes and results of MLST

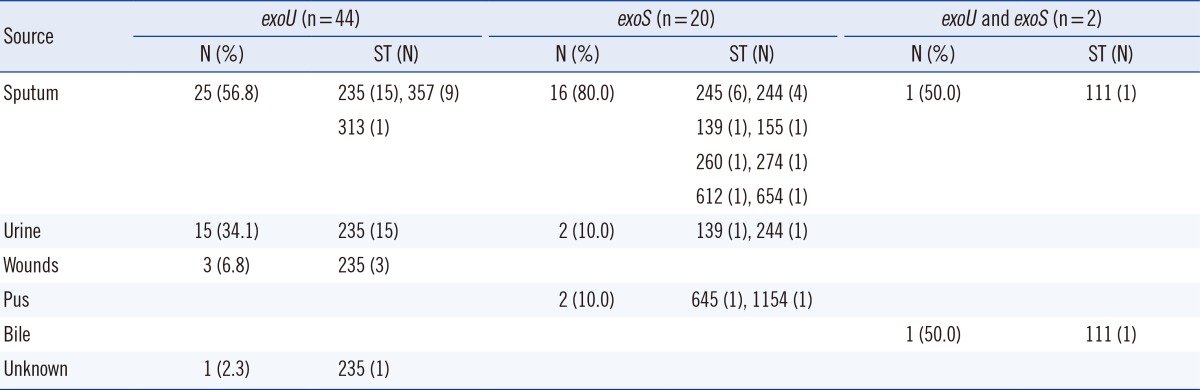

Among the 66 carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains, the site of isolation was known for 65 strains except 1 strain, with most being obtained from sputum (64.6%), followed by urine (26.2%), wounds (4.6%), pus (3.1%), and bile (1.5%; Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of the sequence types among 66 carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains according to disease sites and TTSS genes

Abbreviations: TTSS, the type III secretion system; N, number of strains; ST, sequence type.

A TTSS effector genotype, according to the PCR results, for the exoS and exoU genes revealed that all 66 clinical strains carried exoS and/or exoU (Table 1). Overall, more than a half of the 66 strains (66.7%, 44/66) were exoU+, while 30.3% (20/66) were exoS+; 2 strains were positive for both effector genes (3.0%). The 44 exoU+ strains tested were classified into 3 STs (ST235, 34 strains; ST357, 9 strains; and ST313, 1 strain), and the 20 exoS+ strains analyzed were assigned to 10 STs (ST245, 6 strains; ST244, 5 strains; ST139, 2 strains; ST155, ST260, ST274, ST612, ST645, ST654, and ST1154: 1 strain each).

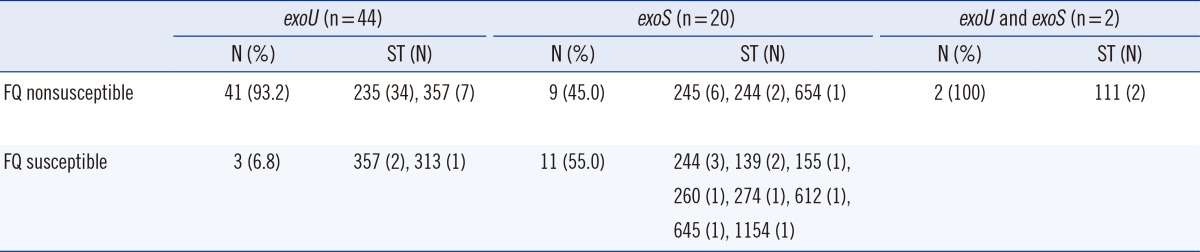

2. The prevalence and degree of fluoroquinolone resistance

All 66 carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains were tested for susceptibility to 2 fluoroquinolone agents. Fifty-two strains (78.8%) exhibited nonsusceptibility to fluoroquinolones, with a ciprofloxacin MIC50 of 64 µg/mL and levofloxacin MIC50 of 32 µg/mL, whereas only 21.2% (14 strains) showed susceptibility (ciprofloxacin: MIC range, <0.25-1.00 µg/mL; levofloxacin: MIC range, <0.25-1.00 µg/mL). The 52 fluoroquinolone nonsusceptible strains were grouped into 6 STs (ST235, 34 strains; ST357, 7 strains; ST245, 6 strains; ST244, 2 strains; ST654, 1 strain; and ST111, 2 strains). Of these, the 41 exoU+ strains were grouped into ST235 and ST357 (Table 2). Notably, exoU+ strains were significantly associated with fluoroquinolone nonsusceptibility compared with exoS+ strains (93.2%, 41/44 vs. 45.0%, 9/20; P≤0.0001).

Table 2.

Prevalence of fluoroquinolone (FQ) resistance and multilocus sequence typing analysis in exoU(+) and exoS(+) Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains

Abbreviations: N, number of strains; ST, sequence type.

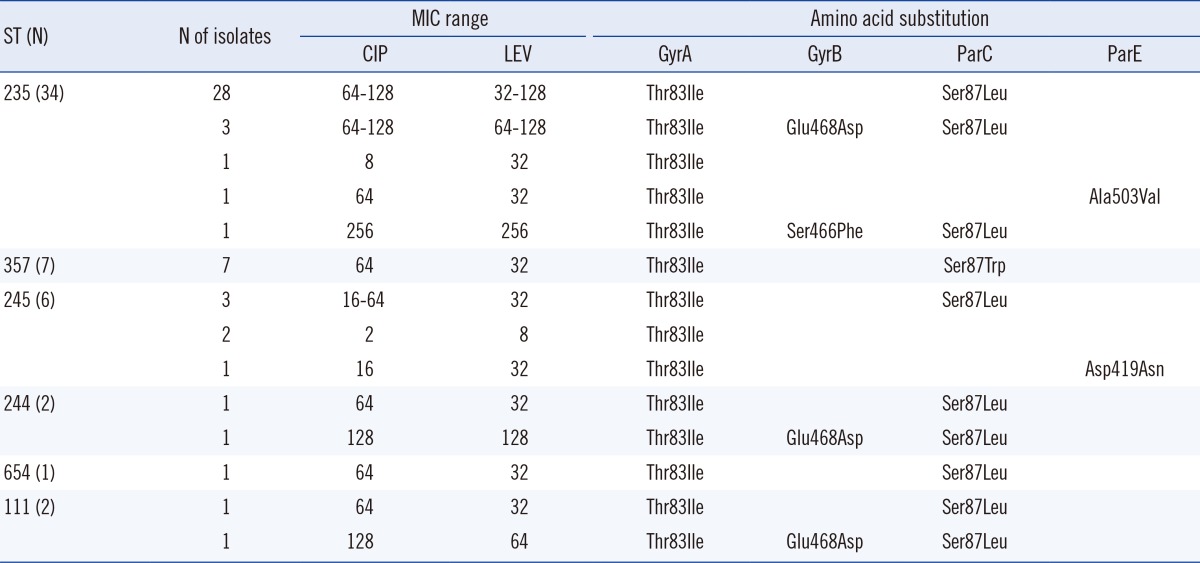

3. Target site mutations

Of the 66 carbapenem-resistant strains, 53 (80.3%) displayed QRDR mutations in 1 or more of the genes analyzed (Table 3). Fifty-two (98.1%) of the 53 mutants possessed a substitution Ile83→Thr in gyrA. This amino acid change was the most frequently identified substitution among strains with active mutations. Of the 53 strains, 4 strains (ciprofloxacin: MIC range, 1-8 µg/mL; levofloxacin: MIC range, 2-32 µg/mL) had only a single mutation in gyrA. The remaining strains (ciprofloxacin MIC range 16-256 µg/mL, levofloxacin MIC range 32-256 µg/mL) had additional substitutions at other positions in gyrB, parC, and parE.

Table 3.

Amino acid substitutions in quinolone resistance-determining regions of GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE subunits in 52 fluoroquinolone-nonsusceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains

Abbreviation: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

Six strains had alterations in gyrB as follows: Glu 468→Asp (5 strains), Ser 466→Phe (1 strain). Glu 468→Asp was a dominant alteration in gyrB, and strains showing 3 alterations, including Glu 468→Asp, had a high level of resistance to ciprofloxacin (MICs, 64-128 µg/mL) and levofloxacin (MICs, 64-128 µg/mL). Furthermore, the change Ser 466→Phe conferred even stronger resistance to ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin (MIC, 256 µg/mL) than did the change at position 468.

Substitution of Leu (40 strains) or Trp (7 strains) for Ser 87 in parC was found in 47 strains, and these strains also displayed an additional substitution, Thr 83→Ile, in gyrA and/or Glu 468→Asp or Ser 466→Phe in gyrB. Characteristically, substitution of Trp for Ser at position 87 in parC was detected only in ST357 strains. Alterations at Asp 419 and Ala 503 in parE were identified in 2 strains with an additional substitution in gyrA.

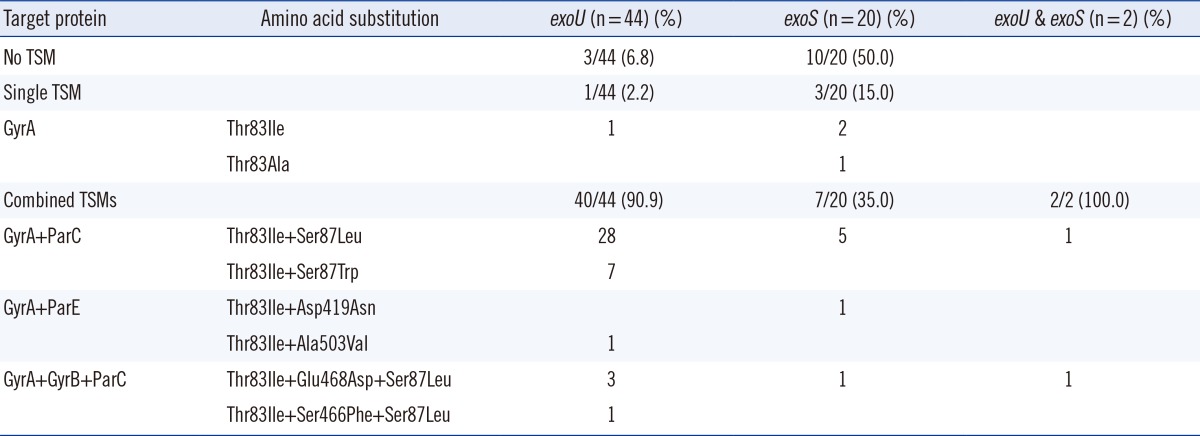

Additionally, single or combined target site mutations (TSMs) showed a significant difference between exoU+ and exoS+ strains (Table 4). Of the 66 strains, 41 exoU+ strains (41/44, 93.2%) had either single or combined TSMs, whereas 10 exoS+ strains (10/20, 50.0%) had no TSMs (P≤0.0001). Moreover, among the 53 strains with active mutations, the exoS+ strains showed an increased number of single TSMs (30.0%, 3/10 vs. 2.4% 1/41; P=0.021), whereas the exoU+ strains had a greater number of combined TSMs (97.6%, 40/41 vs. 70%, 7/10; P=0.021).

Table 4.

Comparison of target site mutations (TSMs) in exoU(+) and exoS(+) Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains

DISCUSSION

Fluoroquinolone resistance among carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains has increased at an alarming rate because of the extensive use of these agents, thereby severely limiting their usefulness [16, 25, 26]. Fluoroquinolone resistance can lead to treatment failure in infections caused by carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa. In particular, fluoroquinolone resistance and expression of TTSS effector proteins are independently associated with poor outcomes in P. aeruginosa infections [3]. TTSS is considered an important determinant of virulence of P. aeruginosa [9, 27]. Using TTSS, P. aeruginosa transports ExoS and ExoU inside a eukaryotic cell. ExoS, a major cytotoxin involved in colonization, invasion, and dissemination of bacteria during infection, is regarded as the most prevalent TTSS effector protein [28]. ExoU has been found to be associated with diverse infections and to have the greatest impact on disease severity [1, 29]. Compared to exoS+ strains, exoU+ strains have been shown to have higher cytotoxicity, which correlates with increased fluoroquinolone resistance [9, 30]. Previous studies found that in the exoU+ genotype, multidrug resistance (MDR) and ciprofloxacin resistance are linked [3, 23]. In addition, our present results show that 93.2% of exoU+ strains are associated significantly with fluoroquinolone nonsusceptibility compared to only 45.0% of the exoS+ strains. The 41 fluoroquinolone nonsusceptible exoU+ strains were grouped into 2 STs (ST235 and ST357). ST235, which has recently been found in a MDR clone, is the founder strain of an international clonal complex, CC235. In addition, Cho et al. [31] reported that IMP-6-producing strains belong to MDR P. aeruginosa ST235. In the present study, all ST235 strains were MDR and featured mainly the virulence gene exoU in contrast to ST357 strains (82.9% vs. 17.1%). Similarly, ST235 carrying the exoU gene was identified in 21 (36.8%) of the 57 carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains collected in 7 Korean hospitals [32].

In particular, only ST357 strains had the substitution Trp→Ser at position 87 in parC, and they showed strong resistance (ciprofloxacin MIC50 of 64 µg/mL, levofloxacin MIC50 of 32 µg/mL). Recently, Matsumoto et al. [33] reported that 2 (9.1%) of 22 levofloxacin-resistant P. aeruginosa strains isolated in Japan have this mutation in parC. In addition, Hrabák et al. [34] showed a wider spread of the IMP-7-producing P. aeruginosa ST357 in Central Europe. As a result, it appears that exoU+ and increased resistance to fluoroquinolones may be coselected traits.

The most prevalent mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance in P. aeruginosa involve mutations in QRDRs. Resistance to fluoroquinolones has been shown to be associated with alterations in the GyrA subunit of DNA gyrase and in the ParC subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV [19, 35, 36].

Of the 53 mutants, 52 (98.1%) possessed a single substitution, Thr to Ile, at position 83 in gyrA. This change was the most common substitution and is known as the principal mutation for the fluoroquinolone resistance of P. aeruginosa strains [37, 38]. The combined alterations, Thr 83→Ile in gyrA and Ser 87→Leu in parC (75.5%, 40 strains), were the second most common mutations in the 53 strains. In P. aeruginosa, like in Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Escherichia coli, amino acid substitutions in parC rarely occurred alone and were usually accompanied by gyrA mutations [39].

Alterations in the 3 QRDRs-gyrA, gyrB, and parC-increased fluoroquinolone resistance further compared to a single mutation in gyrA (MIC range for ciprofloxacin, 64-256 µg/mL vs. 1-8 µg/mL; levofloxacin, 64-256 µg/mL vs. 2-32 µg/mL). Similarly, Parry et al. [40] reported that double mutants show greater MICs than do single mutants, whereas the triple mutant exhibits the highest MIC in Salmonella typhi. In general, the increased number of active mutations is linked to the development of stronger fluoroquinolone resistance.

According to our present study, exoU+ strains were more likely to acquire 2 or more TSMs than exoS+ strains. Furthermore, 10 exoS+ strains had no TSMs (50.0%, 10/20) and showed susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (MIC range, <0.25-1 µg/mL) and levofloxacin (MIC range, <0.25-1 µg/mL). In these data, we observed a robust correlation between TTSS effector proteins and the number of resistance-associated alterations in GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE (QRDR mutations).

In summary, the recent overuse of fluoroquinolones has led to both increased resistance and enhanced virulence in carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa. The present results indicate a specific relationship among the exoU genotype, fluoroquinolone resistance, and differences in active target site mutations conferring resistance. To prevent the spread of fluoroquinolone-resistant exoU+ P. aeruginosa strains, the current widespread use of fluoroquinolones needs to be curtailed, and novel antivirulence therapeutic strategies should be developed as soon as possible.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Shaver CM, Hauser AR. Relative contributions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU, ExoS, and ExoT to virulence in the lung. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6969–6977. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.6969-6977.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galán JE, Collmer A. Type III secretion machines: bacterial devices for protein delivery into host cells. Science. 1999;284:1322–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong-Beringer A, Wiener-Kronish J, Lynch S, Flanagan J. Comparison of type III secretion system virulence among fluoroquinolone-susceptible and -resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:330–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veesenmeyer JL, Hauser AR, Lisboa T, Rello J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence and therapy: evolving translational strategies. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1777–1786. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819ff137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank DW. The exoenzyme S regulon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:621–629. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6251991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato H, Frank DW. ExoU is a potent intracellular phospholipase. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1279–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feltman H, Schulert G, Khan S, Jain M, Peterson L, Hauser AR. Prevalence of type III secretion genes in clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. 2001;147:2659–2669. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-10-2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleiszig SM, Wiener-Kronish JP, Miyazaki H, Vallas V, Mostov KE, Kanada D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa-mediated cytotoxicity and invasion correlate with distinct genotypes at the loci encoding exoenzyme S. Infect Immun. 1997;65:579–586. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.579-586.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy-Burman A, Savel RH, Racine S, Swanson BL, Revadigar NS, Fujimoto J, et al. Type III protein secretion is associated with death in lower respiratory and systemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1767–1774. doi: 10.1086/320737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulert GS, Feltman H, Rabin SD, Martin CG, Battle SE, Rello J, et al. Secretion of the toxin ExoU is a marker for highly virulent Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates obtained from patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1695–1706. doi: 10.1086/379372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Solh AA, Akinnusi ME, Wiener-Kronish JP, Lynch SV, Pineda LA, Szarpa K. Persistent infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:513–519. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-239OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomson CJ. The global epidemiology of resistance to ciprofloxacin and the changing nature of antibiotic resistance: a 10 year perspective. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43(Suppl A):31–40. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.suppl_1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlowsky JA, Draghi DC, Jones ME, Thornsberry C, Friedland IR, Sahm DF. Surveillance for antimicrobial susceptibility among clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii from hospitalized patients in the United States, 1998 to 2001. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1681–1688. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.5.1681-1688.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KW, Kim MY, Kang SH, Kang JO, Kim EC, Choi TY, et al. Korean nationwide surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in 2000 with special reference to vancomycin resistance in enterococci, and expanded-spectrum cephalosporin and imipenem resistance in gram-negative bacilli. Yonsei Med J. 2003;44:571–578. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2003.44.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee K, Jang SJ, Lee HJ, Ryoo N, Kim M, Hong SG, et al. Increasing prevalence of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium, expanded-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, and imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Korea: KONSAR study in 2001. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:8–14. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JY, Ko KS. OprD mutations and inactivation, expression of efflux pumps and AmpC, and metallo-β-lactamases in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from South Korea. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruiz J. Mechanisms of resistance to quinolones: target alterations, decreased accumulation and DNA gyrase protection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:1109–1117. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valdezate S, Vindel A, Echeita A, Baquero F, Cantó R. Topoisomerase II and IV quinolone resistance-determining regions in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia clinical isolates with different levels of quinolone susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:665–671. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.665-671.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mouneimné H, Robert J, Jarlier V, Cambau E. Type II topoisomerase mutations in ciprofloxacin-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:62–66. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vila J, Ruiz J, Goñi P, Jimenez de Anta T. Quinolone-resistance mutations in the topoisomerase IV parC gene of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:757–762. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sáenz Y, Zarazaga M, Briñas L, Ruiz-Larrea F, Torres C. Mutations in gyrA and parC genes in nalidixic acid-resistant Escherichia coli strains from food products, humans and animals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:1001–1005. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: Twentieth Informational supplement, M100-S20. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agnello M, Wong-Beringer A. Differentiation in quinolone resistance by virulence genotype in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JK, Lee YS, Park YK, Kim BS. Alterations in the GyrA and GyrB subunits of topoisomerase II and the ParC and ParE subunits of topoisomerase IV in ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;25:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gasink LB, Fishman NO, Weiner MG, Nachamkin I, Bilker WB, Lautenbach E. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: assessment of risk factors and clinical impact. Am J Med. 2006;119:526.e19–526.e25. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jalal S, Ciofu O, Hoiby N, Gotoh N, Wretlind B. Molecular mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:710–712. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.3.710-712.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holder IA, Neely AN, Frank DW. Type III secretion/intoxication system important in virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in burns. Burns. 2001;27:129–130. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulasekara BR, Kulasekara HD, Wolfgang MC, Stevens L, Frank DW, Lory S. Acquisition and evolution of the exoU locus in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:4037–4050. doi: 10.1128/JB.02000-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hauser AR, Cobb E, Bodi M, Mariscal D, Vallés J, Engel JN, et al. Type III protein secretion is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:521–528. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu DI, Okamoto MP, Murthy R, Wong-Beringer A. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: risk factors for acquisition and impact on outcomes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:535–541. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho HH, Kwon KC, Sung JY, Koo SH. Prevalence and genetic analysis of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST235 isolated from a hospital in Korea, 2008-2012. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2013;43:414–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JY, Peck KR, Ko KS. Selective advantages of two major clones of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates (CC235 and CC641) from Korea: antimicrobial resistance, virulence and biofilm-forming activity. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:1015–1024. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.055426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsumoto M, Shigemura K, Shirakawa T, Nakano Y, Miyake H, Tanaka K, et al. Mutations in the gyrA and parC genes and in vitro activities of fluoroquinolones in 114 clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa derived from urinary tract infections and their rapid detection by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hrabák J, Cervená D, Izdebski R, Duljasz W, Gniadkowski M, Fridrichová M, et al. Regional spread of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST357 producing IMP-7 metallo-β-lactamase in Central Europe. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:474–475. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00684-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakano M, Deguchi T, Kawamura T, Yasuda M, Kimura M, Okano Y, et al. Mutations in the gyrA and parC genes in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2289–2291. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins PG, Fluit AC, Milatovic D, Verhoef J, Schmitz FJ. Mutations in GyrA, ParC, MexR and NfxB in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:409–413. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(03)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akasaka T, Tanaka M, Yamaguchi A, Sato K. Type II topoisomerase mutations in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated in 1998 and 1999: role of target enzyme in mechanism of fluoroquinolone resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2263–2268. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.8.2263-2268.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oh H, Stenhoff J, Jalal S, Wretlind B. Role of efflux pumps and mutations in genes for topoisomerase II and IV in fluoroquiniolone-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Microb Drug Resist. 2003;9:323–328. doi: 10.1089/107662903322762743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shultz TR, Tapsall JW, White PA. Correlation of in vitro susceptibilities to newer quinolones of naturally occurring quinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains with changes in GyrA and ParC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:734–738. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.734-738.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parry CM, Thuy CT, Dongol S, Karkey A, Vinh H, Chinh NT, et al. Suitable disk antimicrobial susceptibility breakpoints defining Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi isolates with reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:5201–5208. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00963-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]