Rothia species are pleomorphic gram-positive bacteria that belong to the Micrococcaceae family [1]. The Rothia genus presently comprises 6 named species, 2 of which are deemed clinically relevant: Rothia dentocariosa and Rothia mucilaginosa [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Another member of the genus, Rothia aeria, a taxon group provisionally named R. dentocariosa genomovar II, is a rare cause of human infections [2, 7] To date, only 6 cases of human infection caused by R. aeria have been reported, including bacteremia [8], neck abscesses [9], respiratory tract infection [10, 11], septic arthritis [12], and infective endocarditis [13]. Although Rothia species have rarely been reported as a causative pathogen of infective endocarditis, no case has been reported in Korea. Moreover, the risk factors for invasive infection by R. aeria are not well defined because of its rarity and the difficulty of correct species identification. Here, we report a case of infective endocarditis caused by R. aeria in a patient taking tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α blocker.

A 53-yr-old Korean man reported fever and chills for 7 days before he visited a nearby clinic and was prescribed an empirical 15-day antibiotic treatment of ceftriaxone and doxycycline. The symptoms improved after antibiotic treatment. However, 10 days after discontinuing treatment, the fever and chills recurred. The patient visited Chonnam National University Hospital (Gwangju, Korea), a 1,000-bed referral center, for further evaluation and treatment. The patient had a history of seropositive ankylosing spondylitis, which had been diagnosed 9 years ago, and had received weekly subcutaneous injections of 25 mg TNF-α blocker (Enbrel; Wyeth, Madison, NJ, USA) for 8 yr. He had also taken 10 mg atorvastatin daily for dyslipidemia. He underwent aortic valvuloplasty, tricuspid valvuloplasty, and a Maze operation owing to severe aortic valve regurgitation with atrial fibrillation 9 yr ago. The patient had also had 4 dental implant placements 2 yr ago. On admission, his vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 120/80 mmHg; pulse rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20/min; and body temperature, 38.2℃. Conjunctival hemorrhage was observed in the right eyelid. A grade 2 early systolic murmur was heard in the third left intercostal space. No Janeway lesions or Osler's nodes were observed. The initial laboratory examination revealed a white blood cell count of 8.1×109/L, hemoglobin of 11.3 g/dL, platelet count of 1.1×1011/L, and C-reactive protein level of 4.51 mg/dL.

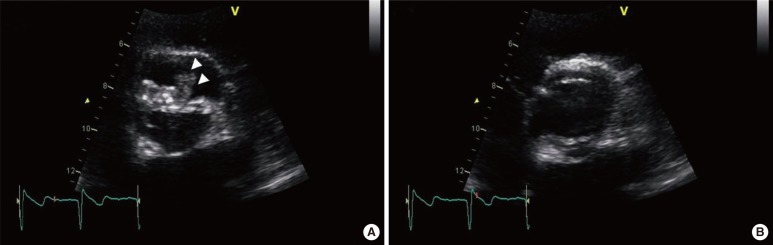

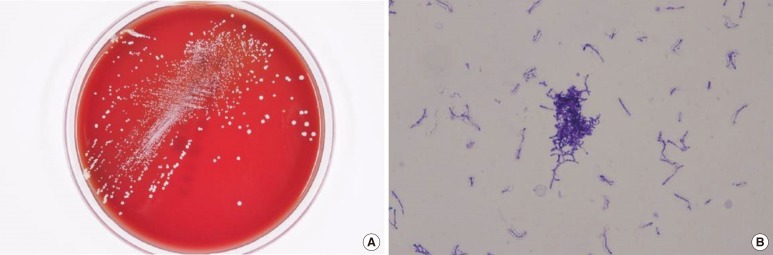

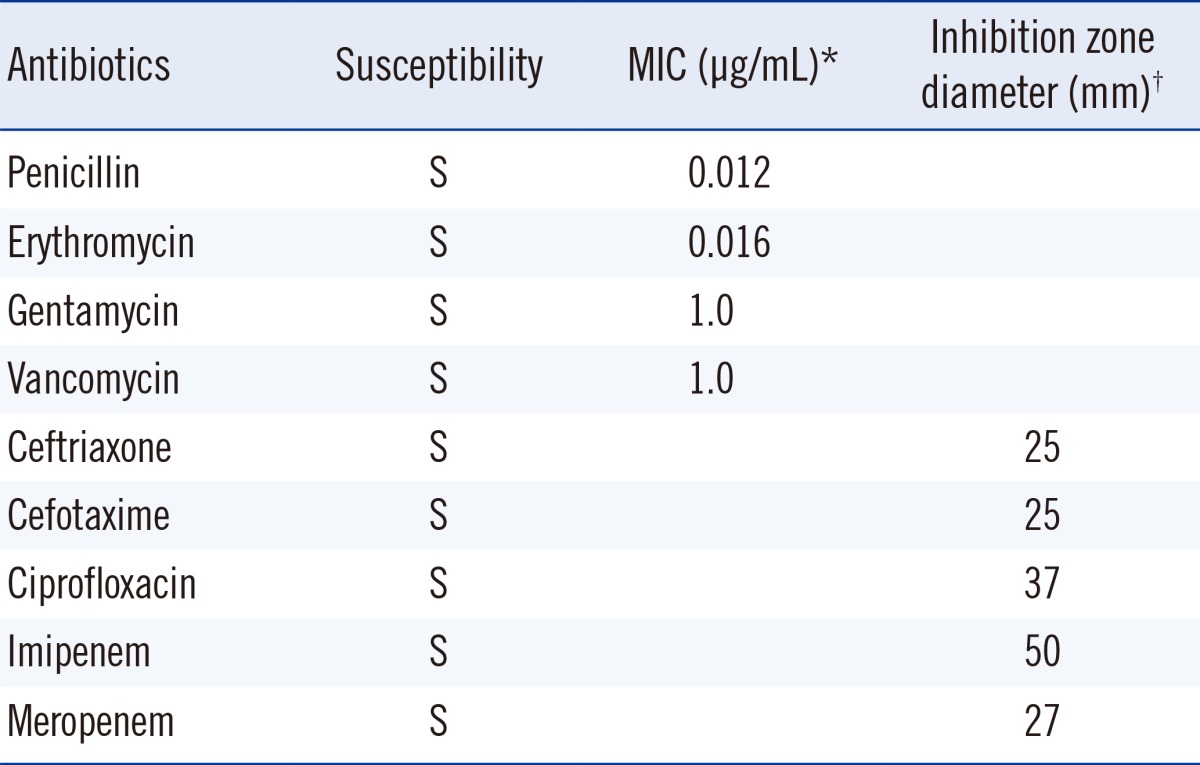

On the day of and a day after admission, 4 sets of blood culture samples were collected in BACTEC Plus Aerobic/F and Anaerobic/F bottles (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD, USA) and incubated in an automated blood culture system (BACTEC 9240; BD Diagnostics). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed vegetation measuring 1.35×0.57 cm at the anterior leaflet of the bicuspid aortic valve and an ejection fraction of 56% (Fig. 1). Empirical antibiotic therapy with 2 g ceftriaxone every 24 hr was started on the second day of admission. All sets of blood cultures yielded the same pleomorphic filamentous gram-positive branching bacilli, resembling the Nocardia species on Gram staining. A pure growth of dry, coarse white and gray colonies was obtained after 48-hr incubation on blood agar plates at 35℃ and 5% CO2 (Fig. 2). The modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining was negative. Biochemical characterization of the isolates was performed using a VITEK 2 GP card (bioMérieux, Mary-l'Etolie, France) and MicroScan Pos Breakpoint Combo panel type 28 (Siemens, Deerfield, IL, USA). The systems identified the microorganism as Micrococcus luteus/lylae (99%) and Micrococcus spp. (98%), respectively. The microorganism was positive for alanine-phenylalanine-proline arylamidase, L-leucine arylamidase, alanine arylamidase, proline arylamidase, tyrosine arylamidase, L-pyroglutamic acid arylamidase, α-glucosidase, and esculin hydrolysis. For definitive identification, the 16S rRNA gene was amplified with universal primers (forward: 5'-AGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3'; reverse: 5'-GTATTGCCGCGGCTGCTG-3') and sequenced. The 830-bp query sequence was 100% homologous to 16S rRNA gene sequences from R. aeria (GenBank accession no. AB753461). Antibiotic susceptibility tests were performed by using Etest (BioMérieux) and the disk diffusion method (BD diagnostics). Since no CLSI protocols exist for R. aeria, we assessed the organism's drug susceptibility utilizing CLSI criteria for staphylococci (M100-S21) [14], as described previously [8, 10, 13]. The antibiotic susceptibility test results are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed echoic mobile vegetation (arrowheads) on the anterior leaflet during diastole (A) and on the bicuspid aortic valve during systole (B).

Fig. 2.

Microbiological examinations. (A) Dry, coarse white and gray Rothia aeria colonies grown on blood agar plates at 35℃ and 5% CO2. (B) Rothia aeria Gram staining (×1,000).

Table 1.

Antibiotic susceptibility of Rothia aeria

The drug susceptibility of Rothia aeria in the present case was determined by using Etest* or the disk diffusion method† according to the 2011 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (M100-S21) criteria for staphylococci.

Abbreviations: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; S, susceptible.

On the third day of admission, the patient was transferred to Asan Medical Center (Seoul, Korea), where he underwent an aortic valve replacement with an annular reconstruction with bovine pericardium. Pathological examination of heart valve and aorta tissues revealed bacterial valvulitis and gram-positive coccobacilli. However, no pathogen was grown from these tissues. Direct 16S rRNA gene PCR of these surgical tissues was not performed. Owing to aortic annular destruction, a complete atrioventricular block occurred after surgery, and a permanent pacemaker was implanted 10 days after the operation. The patient received ceftriaxone 2 g every 24 hr for 4 weeks and was then discharged. He regularly visited Chonnam National University Hospital for 4 months without evidence of recurrence.

Up to 85% of infective endocarditis cases are attributed to staphylococci, streptococci, and enterococci. However, clinicians must be aware of the organisms responsible for the remaining 15% of infective endocarditis [15, 16, 17]. Of Rothia species, R. dentocariosa, a part of the normal community of microbes residing in the oral cavity, has been the most frequent cause of infective endocarditis, with more than 15 reported cases [18]. So far, R. aeria, a gram- and catalase-positive bacillus with its branching, filamentous morphology, has been reported as a cause of infective endocarditis in only 1 case [13]. The present case is the second report of R. aeria infective endocarditis in the English literature and the first reported case in Korea.

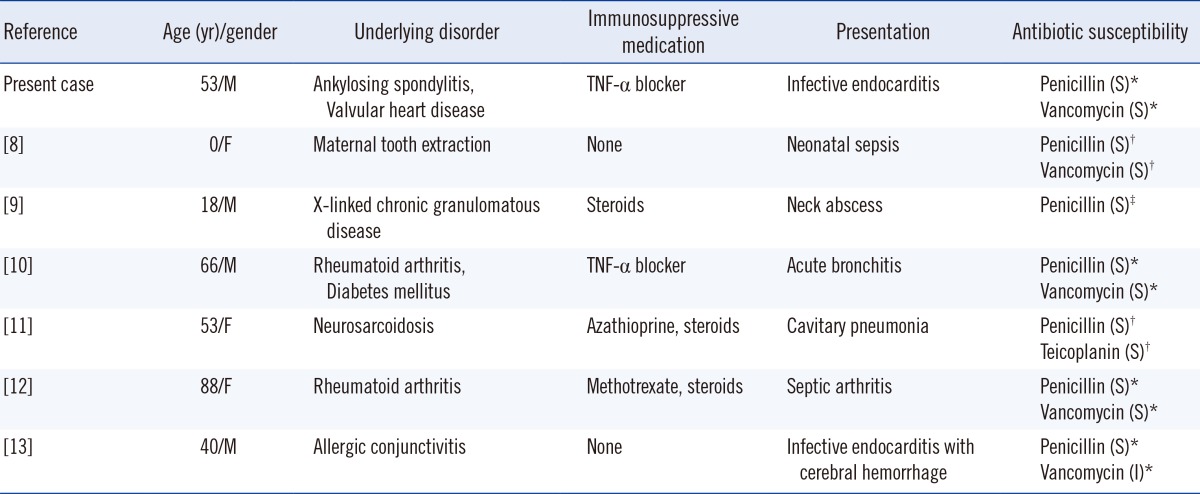

Until now, only 6 cases of invasive R. aeria human infections have been reported (Table 2) [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. Of the 6 reported cases of R. aeria infection, 4 patients were on immunosuppressive drugs, while 1 was a neonate. These cases suggest that R. aeria is an opportunistic pathogen of immunocompromised patients rather than of immunocompetent hosts. The current case also had predisposing risk factors: he was taking an immunosuppressive agent, TNF-α blocker, and had an autoimmune disorder. To date, isolation of R. aeria from clinical specimens has seldom been recognized in Korea. Our isolates were initially misidentified as Micrococcus spp. by 2 commercial identification systems. R. dentocariosa and R. aeria share the same biochemical profiles: positive for nitrate reduction, α-glucosidase, alanine-phenylalanine-proline arylamidase, and esculin hydrolysis and negative for urease [2, 7, 19]. The strain in this case also shared common biochemical characteristics with R. dentocariosa and R. aeria: positive for alanine-phenylalanine-proline arylamidase, α-glucosidase, and esculin hydrolysis and negative for urease. However, the strain was negative for nitrate reduction. The morphological findings were unlike Micrococcus species, which are characterized by gram-positive cocci in a tetrad arrangement; therefore, molecular identification was performed. Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene enabled an accurate species-level identification of R. aeria, which may resemble the Nocardia species in Gram staining. These findings suggest that the paucity of isolations of this species from clinical specimens may reflect, in part, the difficulty in identifying this species.

Table 2.

Reported cases of human infection by Rothia aeria

Antibiotic susceptibilities, shown in parentheses as S, I, and R, were determined by using Etest*, the disk diffusion method†, or MicroScan microdilution‡, and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute staphylococcal standards.

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

In summary, this is the first case report of infective endocarditis caused by R. aeria in Korea, and our case highlights that R. aeria should be considered as a rare cause of infective endocarditis, particularly in patients taking immunosuppressive medication. Therefore, as a gram-positive bacillus, R. aeria should also be considered a pathogen, and correct species identification and antibiotic susceptibility tests are warranted to ensure the use of appropriate antibiotics.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Shin JH, Shim JD, Kim HR, Sinn JB, Kook JK, Lee JN. Rothia dentocariosa septicemia without endocarditis in a neonatal infant with meconium aspiration syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4891–4892. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4891-4892.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Funke G, Bernard KA. Coryneform Gram-positive rods. In: Versalovic J, Carroll KC, et al., editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 10th ed. Washington DC: ASM Press; 2011. pp. 413–442. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ergin C, Sezer MT, Agalar C, Katirci S, Demirdal T, Yayli G. A case of peritonitis due to Rothia dentocariosa in a CAPD patient. Perit Dial Int. 2000;20:242–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shakoor S, Fasih N, Jabeen K, Jamil B. Rothia dentocariosa endocarditis with mitral valve prolapse: case report and brief review. Infection. 2011;39:177–179. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho EJ, Sung H, Park SJ, Kim MN, Lee SO. Rothia mucilaginosa pneumonia diagnosed by quantitative cultures and intracellular organisms of bronchoalveolar lavage in a lymphoma patient. Ann Lab Med. 2013;33:145–149. doi: 10.3343/alm.2013.33.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McWhinney PH, Kibbler CC, Gillespie SH, Patel S, Morrison D, Hoffbrand AV, et al. Stomatococcus mucilaginosus: an emerging pathogen in neutropenic patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:641–646. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.3.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Kawamura Y, Fujiwara N, Naka T, Liu H, Huang X, et al. Rothia aeria sp. nov., Rhodococcus baikonurensis sp. nov. and Arthrobacter russicus sp. nov., isolated from air in the Russian space laboratory Mir. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:827–835. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monju A, Shimizu N, Yamamoto M, Oda K, Kawamoto Y, Ohkusu K. First case report of sepsis due to Rothia aeria in a neonate. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1605–1606. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02337-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falcone EL, Zelazny AM, Holland SM. Rothia aeria neck abscess in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease: case report and brief review of the literature. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:1400–1403. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9726-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michon J, Jeulin D, Lang JM, Cattoir V. Rothia aeria acute bronchitis: the first reported case. Infection. 2010;38:335–337. doi: 10.1007/s15010-010-0012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiyamuta H, Tsuruta N, Matsuyama T, Satake M, Ohkusu K, Higuchi K. First case report of respiratory infection with Rothia aeria. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2010;48:219–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verrall AJ, Robinson PC, Tan CE, Mackie WG, Blackmore TK. Rothia aeria as a cause of sepsis in a native joint. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2648–2650. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02217-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarumoto N, Sujino K, Yamaguchi T, Umeyama T, Ohno H, Miyazaki Y, et al. A first report of Rothia aeria endocarditis complicated by cerebral hemorrhage. Intern Med. 2012;51:3295–3299. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Perfomance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Wayne, PA: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2011. Twenty-first Informational supplement, M100-S21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habib G, Hoen B, Tornos P, Thuny F, Prendergast B, Vilacosta I, et al. Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): the Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and the International Society of Chemotherapy (ISC) for Infection and Cancer. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2369–2413. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim MH, Chung DR, Kim WS, Park KS, Ki CS, Lee NY, et al. First case of Bartonella quintana endocarditis in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:1433–1435. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.11.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang HC, Park WB, Kim HB, Kim EC, Oh MD. Clinical features and rate of infective endocarditis in non-faecalis and non-faecium enterococcal bacteremia. Chonnam Med J. 2011;47:111–115. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2011.47.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong R, Mebazaa A, Heitz B, De Briel DA, Kiredjian M, Raskine L, et al. Case of triple endocarditis caused by Rothia dentocariosa and results of a survey in France. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:309–310. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.309-310.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko KS, Lee MY, Park YK, Peck KR, Song JH. Molecular identification of clinical Rothia isolates from human patients: proposal of a novel Rothia species, Rothia arfidiae sp. nov. J Bacteriol Virol. 2009;39:159–164. [Google Scholar]