Abstract

The regenerative capacity of tissues to recover from injury or stress is dependent on stem cell competence, yet the underlying mechanisms that govern how stem cells detect stress and initiate appropriate responses are poorly understood. In this issue of the JCI, Cho and Yusuf et al. demonstrate that the purinergic receptor P2Y14 may mediate the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell regenerative response.

Senescence and stem cell decline

Cellular senescence, a state of permanent irreversible growth arrest, was initially described over half a century ago by Leonard Hayflick and Paul Moorhead, who observed that normal human fibroblasts cease to replicate after 50 to 60 cellular divisions (1). This barrier to everlasting cellular proliferation later became termed the “Hayflick limit,” denoting the loss of proliferative potential even though the cell remains viable and metabolically active. While this phenomenon was originally connected to long-term in vitro cell propagation, cellular senescence is now understood to be a complex mechanism that may limit cell growth as well as prevent cancer in vivo and that can be initiated in response to a variety of cellular stresses, including oxidative damage, telomere shortening, DNA damage, and gene deregulation (2–4).

As with the majority of tissues, the hematopoietic system exhibits signs of age-related decline, including immune dysfunction, decreased red blood cell production, increased incidence of malignancies, and impaired recovery from injury, much of which appears to arise through cell autonomous changes in the HSC compartment (5–8). These age-related changes in the HSC compartment appear to be driven by diverse processes, including DNA damage accumulation (9, 10), loss of cell polarity (11), epigenetic changes of DNA methylation and histone modifications (12, 13), and clonal dominance of lineage-biased HSCs (7). While age-related decline in many tissues is thought to coincide with increased cellular senescence of their respective stem and progenitor cell populations (14), in the HSC compartment, it is unclear whether senescence promotes physiological aging, though classical senescence markers, such as p16INK4A, do not appear to be robustly upregulated in aged HSCs (13, 15). It should be noted that there is evidence of p16INK4A-dependent modulation of HSC potential under conditions of extreme hematopoietic stress, such as serial transplantation (16).

Loss of P2Y14 leads to reduced HSC potential in response to stress

In this issue, Cho, Yusuf, and colleagues provide evidence that stress-induced senescence in hematopoietic stem progenitor cells (HSPCs) is regulated through the G-coupled cell-surface receptor P2Y14 (17). HSCs give rise to all blood effector cells for the life of an individual, and the capacity to constantly replenish the hematopoietic compartment requires a careful balance among HSC fate decisions, including self renewal, quiescence, apoptosis, and multilineage differentiation. In contrast with HSCs, differentiated effector populations frequently have a short life span, measured in days, resulting in a huge daily cell turnover that necessitates tight homeostatic control of the upstream HSPC populations, where transit amplification occurs. Under situations of stress, such as irradiation or chemotherapy, a portion of the HSPC pool may be lost, leading to myelosuppression (decreased red cell, white cell, and platelet numbers), and in such cases, the surviving HSPCs must increase self renewal and differentiation to repopulate required cell populations. How HSPCs integrate stress signals to invoke the appropriate stress responses remains unclear. Cho, Yusuf, and colleagues have revealed that P2Y14 regulates the HSPC response to stress. Specifically, the authors demonstrate that HSPCs lacking P2Y14 are not at a disadvantage for restoring hematopoietic populations when cotransplanted with equivalent WT HSPCs in lethally irradiated mice under steady state conditions; however, under various stress conditions, including serial transplantation, radiation, and chemotherapy, cells lacking P2Y14 were less competitive than WT cells. As a result of the stress-induced loss of competitiveness, there was a decline in P2Y14-deficient HSPCs and total peripheral blood chimerism (Figure 1). Interestingly, the loss of functionality in P2Y14-deficient cells occurred concurrently with increased detection of several classical senescence biomarkers, including p16INK4A, greater β-gal (SA–β-gal) activity, and increased ROS, implicating cellular senescence as a possible consequence of P2Y14 deficiency during stress. Furthermore, Cho, Yusuf, and colleagues demonstrated that the enhanced susceptibility to irradiation stress in P2Y14-deficient HSPCs could be alleviated through administration of the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) or inhibition of p38 MAPK, an important mediator of the ROS-response pathway, indicating that dysfunctional ROS management may be a significant underlying contributor (17).

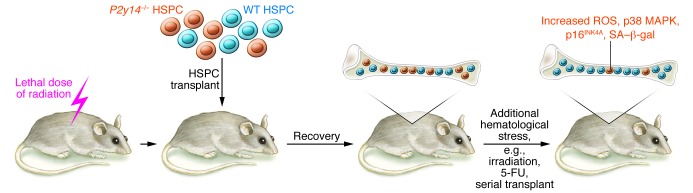

Figure 1. HSPCs lacking P2Y14 have reduced functionality.

Competitive transplantation of WT and P2Y14-deficient HSPCs into an irradiated animal results in equal repopulation of the hematopoietic environment. Following blood reconstitution, P2y14–/– HSPCs exhibit a competitive disadvantage if mice are exposed to additional hematological stress, such as irradiation or serial transplantation. Furthermore, in response to stress, P2Y14-deficient HSPCs show several markers of senescence, including increased ROS, p38 MAPK, p16INK4A, and SA–β-gal.

HSC function has previously been shown to diminish as a consequence of ROS dysregulation, leading to premature exhaustion and shortened lifespan. For example, mice deficient in ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) experience hematopoietic failure, which is largely abrogated by NAC treatment (18). Similarly, deletion of genes encoding forkhead box transcription factors (FoxOs) has been shown to negatively affect HSC function and numbers through increased ROS production and subsequent HSC apoptosis (19–21). Together, these results indicate that increased ROS levels diminish HSC function; therefore, it is likely that the increased ROS detected in P2Y14-deficient HSPCs is playing an integral role in the observed phenotypes through cellular oxidative damage and perhaps apoptosis, although future work will be needed to elucidate the exact connection between the P2Y14 receptor and ROS management.

Conclusions and future directions

Cho, Yusuf, and colleagues have shown that HSPCs lacking the P2Y14 receptor are compromised in their ability to withstand and recover from several types of stress. The authors make a strong biochemical case for a senescence-based mechanism explaining the diminished function of P2Y14-deficient HSPCs during stress, though the development of functional assays that uncouple senescence from other processes that diminish HSC potential, such as apoptosis, will likely be required to definitively elucidate how P2Y14 mediates the HSPC stress response (10, 22). If PY214-deficient HSCs within the animal model system developed by Cho, Yusuf, and colleagues do indeed prove to be functionally senescent, then this could be an exciting model system for studying the onset of stress-induced senescence within the HSC compartment. A better understanding of the regulators of HSC stress response has important implications for regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgments

D.J. Rossi is a New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Investigator.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Derrick Rossi has an ownership stake and provides consultation for Moderna Therapeutics.

Citation for this article:J Clin Invest. 2014;124(7):2846–2848. doi:10.1172/JCI76626.

See the related article beginning on page 3159.

References

- 1.Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1961;25:585–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campisi J, d’Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(9):729–740. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. The essence of senescence. Genes Dev. 2010;24(22):2463–2479. doi: 10.1101/gad.1971610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salama R, Sadaie M, Hoare M, Narita M. Cellular senescence and its effector programs. Genes Dev. 2014;28(2):99–114. doi: 10.1101/gad.235184.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi DJ, et al. Cell intrinsic alterations underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(26):9194–9199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503280102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dykstra B, Olthof S, Schreuder J, Ritsema M, de Haan G. Clonal analysis reveals multiple functional defects of aged murine hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208(13):2691–2703. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beerman I, et al. Functionally distinct hematopoietic stem cells modulate hematopoietic lineage potential during aging by a mechanism of clonal expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(12):5465–5470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000834107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pang WW, et al. Human bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells are increased in frequency and myeloid-biased with age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(50):20012–20017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116110108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossi DJ, Bryder D, Seita J, Nussenzweig A, Hoeijmakers J, Weissman IL. Deficiencies in DNA damage repair limit the function of haematopoietic stem cells with age. Nature. 2007;447(7145):725–729. doi: 10.1038/nature05862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beerman I, Seita J, Inlay MA, Weissman IL, Rossi DJ. Quiescent hematopoietic stem cells accumulate DNA damage during aging that is repaired upon entry into cell cycle. Cell Stem Cell. 2014:pii:S1934-5909(14)00153-2. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Florian MC, et al. Cdc42 activity regulates hematopoietic stem cell aging and rejuvenation. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(5):520–530. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beerman I, et al. Proliferation-dependent alterations of the DNA methylation landscape underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(4):413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun D, et al. Epigenomic profiling of young and aged HSCs reveals concerted changes during aging that reinforce self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14(5):673–688. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sperka T, Wang J, Rudolph KL. DNA damage checkpoints in stem cells, ageing and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(9):579–590. doi: 10.1038/nrm3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attema JL, Pronk CJ, Norddahl GL, Nygren JM, Bryder D. Hematopoietic stem cell ageing is uncoupled from p16 INK4A-mediated senescence. Oncogene. 2009;28(22):2238–2243. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janzen V, et al. Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a. Nature. 2006;443(7110):421–426. doi: 10.1038/nature05159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho J, et al. Purinergic P2Y14 receptor modulates stress-induced hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell senescence. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(7):3159–3171. doi: 10.1172/JCI61636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito K, et al. Regulation of reactive oxygen species by Atm is essential for proper response to DNA double-strand breaks in lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2007;178(1):103–110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tothova Z, et al. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell. 2007;128(2):325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyamoto K, et al. Foxo3a is essential for maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(1):101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yalcin S, et al. Foxo3 is essential for the regulation of ataxia telangiectasia mutated and oxidative stress-mediated homeostasis of hematopoietic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(37):25692–25705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao L, et al. Total body irradiation causes long-term mouse BM injury via induction of HSC premature senescence in an Ink4a- and Arf-independent manner. Blood. 2014;123(20):3105–3115. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-515619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]