Abstract

Exposure to loud sounds results in a mild to profound degree of temporary or permanent hearing loss. Though occupational noise exposure remains the most commonly identified cause of noise-induced hearing loss, potentially hazardous noise can be encountered during recreational activities. Unfortunately not much attention is being given to the increasing trend of prolonged exposure to noisy environment, in the younger generation of Indians. The purpose of our study was to know the knowledge of college students about the harmful effects of loud music, prevailing practices with regard to exposure to recreational music and the subjective effects that this exposure is causing if any. Cross Sectional survey of College Students (n = 940), from randomly selected colleges of Delhi University. Majority of students listened to music using music-enabled phones; earphones were preferred and 56.6 % participants listened to music on a loud volume. Effects experienced due to loud sound were headache (58 %), inability to concentrate (48 %), and ringing sensation in the ear (41.8 %). Only 2.7 % respondents used ear protection device in loud volume settings. Twenty-three percent respondents complained of transient decreased hearing and other effects after exposure to loud music. 83.8 % knew that loud sound has harmful effect on hearing but still only 2.7 % used protection device. The survey indicates that we need to generate more such epidemiological data and follow up studies on the high risk group; so as to be able to convincingly sensitize the Indian young generation to take care of their hearing and the policy makers to have more information and education campaigns for this preventable cause of deafness.

Keywords: Noise induced hearing loss, Leisure music, Recreational music

Introduction

Noise induced hearing loss (NIHL) is the gradual decline in auditory function following long term, repeated exposure to loud noise. The hearing impairment is sensorineural and usually bilateral. The impairment may be temporary or permanent and may range from mild to profound in degree.

Occupational noise exposure remains the most commonly identified cause of NIHL but potentially hazardous noise can be encountered during recreational activities [1].

It is being observed that our young generation is increasingly being exposed to noisy environments, as they frequently engage in such recreational activities like attending discotheques, rock concerts, gyms, videogame parlours or listen to personal music players at a high volume. Listening to amplified music can be responsible for hearing damage of the same nature as that caused by industrial noise. Western literature has various studies, where authors have documented the detrimental effect of loud sound on hearing [2, 3].

Apart from hearing loss, noise exposure also has other non-measurable effects such as irritability, insomnia and inability to concentrate. Various other indirect effects on health and wellbeing have been documented [4], stressing the need for research on noise pollution in India.

In the Indian context, research on this aspect of exposure to loud recreational music as a cause of NIHL is still in the nascent stage, though we see more and more youngsters engaged in noisy activities.

The aim of our study was to study the music listening habits of college students in Delhi, their knowledge about harmful effects of loud sound and prevention and control measures; the subjective effects that this exposure is causing if any, and to get preliminary data on the intensity of sound in various exposure settings.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Cross-sectional study.

Study Area

Colleges of Delhi University selected randomly.

Study Population

University students of Delhi.

Study Sample

We did not come across any study on prevalence of effects of loud recreational music among students in a university setting in India; hence no hypothesis was formulated for prevalence estimates. Hence an arbitrary convenience sample of 1,000 respondents was selected from various colleges of University of Delhi.

Data Collection Tools

A pre-tested and internally validated questionnaire was used to collect data to satisfy our aims and objectives. The questionnaire was self-administered and consisted of semi open-ended questions. The research was in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the institutional research project advisory committee. The participants’ written informed consent was obtained on the basis of a procedure that is officially approved by our institution.

The exposure levels i.e. the intensity of sound that the students are exposed to were measured in the field (discotheques, rock concerts etc.), using a well-calibrated sound level meter.

Confidentiality of the questionnaire was ensured and participation in the study was purely voluntary.

Data Collection

The questionnaire was distributed amongst the students and then collected later. The students included under graduate and postgraduate students. Students with history of exposure to sudden loud sound such as a blast or explosion; history of chronic suppurative otitis media or a history of congenital deafness were excluded.

The sound level recordings were carried out at places of loud recreational music by a team of two people at the same places that were reported to be frequently visited by the students under similar settings. The instrument used was a calibrated integrating average sound level meter (Type 2240); Bruel and Kajer. The sound level meter was used at different distances from the speakers and at different times representing early, mid and late evening periods. Measurements were conducted at discotheques, private parties, rock shows during the college festival, dance parties and in a closed car with the music player on the preferred output setting. The measurement parameter was the equivalent continuous A-weighted noise level (LAeq) in decibels.

Data Management and Data Analysis

All questionnaires were pre coded and a spread sheet was created using MS excel software. Descriptive tables were generated and statistical analysis was performed using logistic regression analysis using SPSS version 17.0.

Results

Total 940 participants satisfactorily completed the questionnaire. The age group was 16–30 years. The mean age of the participants was 20 years with SD = 2.0. 95.8 % of the participants were in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd year of graduation.

Music Listening Practice

Majority of the participants (99 %) were music listeners. They listened to a mixture of different genre of music and more than 4/5th of the participants had Hindi film music in their music player playlist. The other popular genres were rock and pop music. Other forms of music listened to were Arabian, Bhajan, Bhangra, Bhojpuri, Country songs, Ghajal, Sufi, Heavy Metal, Alternate Metal, Soft rock, Tamil songs etc.

Majority of the participants were daily music listeners. Only <5 % were infrequent music listeners i.e. less than once a week (Fig. 1). 77.4 % of the participants listened to music for an hour or less at a stretch. Only 22.6 % engaged in listening to music for hours. Music enabled phones were the most common music player used. Personal computers/Laptops and Music systems were used by more than 50 % of the participants.

Fig. 1.

Frequency of listening to music (x axis) against percentage of respondents (y axis)

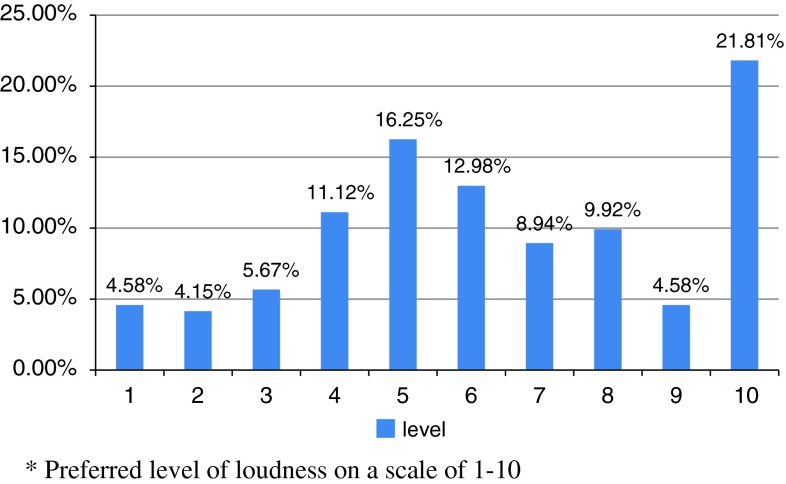

Most participants (56.6 %) had a tendency to listen to music on high volume (Fig. 2). 33.37 % of the participants reported asking others to reduce the volume of music systems e.g. in cars or parties, while 55.12 % of the respondents reported occasions when they were asked by others to reduce the volume of their music player.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of respondents with the preferred level of loudness of music system

Earphones were more commonly used for listening to music as compared to head phones (86.5 %, n = 874). It was seen that the respondents were more attuned to loud volume while using earphones/headphones for music listening as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Preferred level of loudness of headphones/earphones (n = 917)

Attending music gatherings were infrequent events, with 56.73 % of the participants attending musical events, only once in a month. Twenty-fifth percentile of the respondents had an average frequency of once in 2 weeks, while median of the attendance was once in 4 weeks.

Open air music gatherings e.g. music-in-the-park were attended by 36 % of the respondents while 46.6 % said they attended both open air music gatherings and closed space entertainment venues e.g. discotheques. In places of social gatherings, majority of the participants (74.32 %) liked the music to be played loud.

Places frequented for recreation by the respondents of the survey were: malls, movies, parties, college functions, bars and discotheques, concerts, parks, pubs, dance parties, restaurants, clubs, cultural events, gathering at friends place and hostel rooms etc.

Knowledge

Effects of Loud Sound on Hearing

Majority (83.8 %) of the participants thought that loud sound has a harmful effect on hearing. 74.53 % respondents opined that loud sound has “some” effect on health.

Most of the respondents had discussed with their parents the effects of loud sound on health. Some had had a discussion at some point with the bartender, girlfriend or siblings.

The main sources of information about the effects of loud music on health were newspapers. Other common sources were books, television, doctors, health magazines, hospitals, hoardings, internet and parents.

Majority of the respondents had experienced some form of effect of loud music on health (Table 1). The most common effects experienced due to loud sound were headache (58 %), inability to concentrate (48 %), and ringing sensation in the ear (41.8 %).

Table 1.

Percentage of respondents having suffered from different effects of loud sound on health (n = 500)

| Effects | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased hearing | 115 | 23 |

| Ringing sensation in the ear | 209 | 41.8 |

| Headache | 290 | 58 |

| Vertigo | 26 | 5.2 |

| Irritability | 172 | 34.4 |

| Insomnia | 68 | 13.6 |

| Inability to concentrate | 240 | 48 |

Only a small proportion (2.7 %) of the respondents made use of ear protective device in noisy gatherings. Out of those who wore ear protection devices, 68 % were aware that loud music is harmful.

Noise Control Regulations

45.27 % respondents were aware that some noise controlling regulations were in place out of which the most quoted was that loudspeakers are not allowed after 11 p.m in Delhi. Twenty-five percent said there were no legislations and 30 % said they did not know. About 83 % respondents suggested that noise controlling regulations should be in place, but 7 % of the respondents felt that there should not be any such regulations.

Exposure Levels at Noisy Places

The equivalent continuous A-weighted noise level, recorded in discotheques (average of various readings at different times and at different distances from the speaker) was in the range of 98–120 dB. Using the sound level meter we could not get very accurate ear level readings of sound from the personal music players, but still the levels recorded were in the range of 90–110 dBA. In social gatherings/open air concerts also the sound exposure range was 85–100 dBA.

For loudness, the respondents were asked to mark on a scale of range 1–10 with 10 being the loudest. This scale was used for response to loudness, volume of headphone and preference for intensity of loudness at music concerts. Subsequently responses were grouped as low (1–5 on scale) and high (6–10 on scale).

Bi-variate analysis did not show any significant association between the predictor and outcome variables.

A logistic regression analysis was carried out to see if there were any predictors of adverse effects of loud sound experienced by the respondents. For this analysis, outcome variable was “if ever experienced any effect of loud sound” and the predictor variables were frequency of listening to music, duration of listening music at a stretch, loudness of sound in the music system, preference of loudness at music events/concerts and the number of years since enrolment at college as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of logistic regression

| Variables | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | p | OR | 95 % CI | p | |

| Frequency of listening to music | ||||||

| Less than twice a week | Ref | Ref | ||||

| More than twice a week | 0.85 | 0.56–1.30 | 0.27 | 1.28 | 0.80–2.03 | 0.29 |

| Duration of listening to music | ||||||

| ≤30 min | Ref | Ref | ||||

| >30 min | 1.03 | 0.84–1.26 | 0.42 | 1.07 | 0.79–1.46 | 0.66 |

| Loudness | ||||||

| Low | Ref | Ref | ||||

| High | 1.1 | 0.83–1.47 | 0.28 | 1.13 | 0.72–1.77 | 0.59 |

| Use of headphone | ||||||

| Low volume | Ref | Ref | ||||

| High volume | 1.1 | 0.82–1.48 | 0.28 | 0.91 | 0.64–1.31 | 0.92 |

| Preference for loudness at musical events | ||||||

| Low intensity | Ref | Ref | ||||

| High intensity | 0.96 | 0.69–1.33 | 0.43 | 1.08 | 0.74–1.57 | 0.69 |

| Years in medical college | ||||||

| 1st year | 0.77 | 0.35–1.72 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.35–1.70 | 0.54 |

| 2nd year | 0.78 | 0.53–1.14 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 0.40–1.89 | 0.74 |

| 3rd year | 0.84 | 0.56–1.26 | 0.37 | 0.95 | 0.44–2.03 | 0.89 |

| 4th year or above | Ref | Ref | ||||

The only variable found to be significant was that respondents who reported listening to music less frequently (less than twice a week) were 38 % less likely (95 % CI 39.2–99.8) to have suffered from any adverse effect (p = 0.049).

Discussion

Sounds of sufficient intensity and duration have been found to be harmful for the sensitive inner ear structures and may lead to temporary or permanent hearing loss. Hence it is important to have surveys such as ours to assess some aspects of exposure to recreational music. The first audiometric sign of NIHL resulting from broadband noise is usually a loss of sensitivity in the higher frequencies, from 3,000 through 6,000 Hz. With continuing exposure, NIHL levels off in higher frequencies but continues to worsen in low frequencies. An important consequence is difficulty in understanding speech, leading to fatigue and anxiety in attending social activities occurring in noisy settings [5]. It has been observed that the prevalence of noise induced threshold shift increases with age, because of accumulated exposures over time. In a study it was found that children aged 12–19 years had a significantly higher prevalence estimate (15.5 %) than 6–11 year olds (8.5 %) [6].

Though noise levels due to aircraft noise, traffic or in industries are being monitored in India, as yet there is no regular monitoring of noise due to leisure sounds, unlike western countries, where for example, through a national project in Sweden, it was found that 42 % of participating municipalities exceeded the highest recommended sound pressure levels for leisure sounds during festival and concert events, thus exposing the visitors to harmful sound levels [7].

Personal listening devices (PLDs) allow users to listen to music uninterrupted for prolonged periods and at levels that may pose a risk for hearing loss. Listeners using ear bud earphones are more at risk, because they fail to attenuate high ambient noise levels and necessitate increasing volume for acoustic enjoyment [8]. Ear phones are the more common modality used by music listeners [9], as is also found in our study (86.5 %, n = 874), thus putting them in the higher risk group. In a study by Vogel et al. [10], 90 % participants reported listening to music through earphones on MP3 players; 28.6 % were categorized as listeners at risk for hearing loss due to estimated exposure of 89 dBA for ≥1 h per day. A study from India also found that about 30 % in a group of 70 young adults listened to music above the safety limits (80 dBA for 8 h) [11].

In another study, 83.1 % of study participants used PLDs regularly, of whom 77.7 % used it for more than 1 h a day. Eighteen percent were aware that prolonged use of PLDs could be harmful to their health and overall, 12.4 % experienced temporary hearing loss [12].

In a Dutch study comprising of 1,687 adolescents, ninety percent reported listening to music through earphones; 32.8 % were frequent users, 48.0 % used high volume settings, and only 6.8 % always or nearly always used a noise-limiter [13]. In our study too use of earphones was preferred; majority of the participants were daily music listeners; 56.6 % preferred listening to music loud and only 2.7 % used ear protection device. Our survey thus indicates that our youngsters are also facing the risk of increased exposure to loud leisure sounds.

Various studies have shown that exposure to loud recreational music over prolonged periods of time leads to various effects on hearing and health [14–19]. These studies bought out recommendations for young people, who are perhaps not aware of the importance of good hearing to their future productivity and quality of life.

Night clubs and discotheques have become a significant part of the entertainment scene for many young adults. In our study 56.73 % of participants reported attending musical events, but only once in a month; 46.6 % reported attending both open air music gatherings and closed space entertainment venues e.g. discotheques. In these places, majority of participants (74.32 %) liked the music to be played loud. In a study by Rosanowski et al. [20] in a similar cohort, on an average the participants frequented a discotheque 1.4 times a month.

While exposure levels do vary, a typical night club attendee was found to experience an equivalent continuous A-weighted noise level of around 98 dB for up to 5 h, with a sustained period of regular club attendance contributing significantly to whole-of-life noise exposure. The average noise levels measured at the clubs sampled in our study (98–120 dBA), agree well with those measured in similar studies (LAeq = 97.9 dB, SD = 5.5) [21] and range of 104.3–112.4 dBA [22]; indicating a similar exposure level in our youngsters.

According to our survey the most common effects experienced due to loud sound were headache (58 %), inability to concentrate (48 %), and ringing sensation in the ear (41.8 %) (Table 1). Similar observations have been made in other studies; transient tinnitus (58 %), transient hearing loss (37 %) [20]; and tinnitus (84.7 %), hearing disturbance in (37.8 %) [23].

Though 39.8 % respondents in a study thought it was very likely that noise levels at concerts could damage their hearing; 80.2 % said that they never wore hearing protection at such events [23], a behavior also seen in our survey (only 2.7 % wore protection device). A study in Sweden revealed that students who reported tinnitus and other hearing related symptoms protected their hearing to higher extent and were more worried [24]. In our study though ear protection device was worn in only 2.7 % respondents; 68 % of these were aware that loud sound is harmful for hearing. This behavior reflects a lack of awareness regarding the seriousness of frequent exposures to loud music or lack of motivation towards hearing protection.

The regression analysis showed only one significant variable associated with adverse effect of noise, however subjectivity in response cannot be ruled out altogether, hence no conclusive evidence can be derived from this finding.

Based on insights gained through our survey and after review of literature we would like to conclude that the respondents are using personal music players for prolonged durations and at high volume settings. Many respondents have also experienced the effects of loud sound on hearing and health. Though our study is limited by lack of audiometric assessment of subjects, the exposure levels have been found to be similar to that reported in literature.

Out of the total respondents the cohort of regular listeners to loud music need to be counselled and also followed up for development of hearing loss. There is a need for further research to better define the risk criterion for exposure to loud recreational music, so that the youngsters can be better warned when exposure is to be limited and the use of protective ear devices can be encouraged.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by an Intramural grant from the University College of Medical Sciences, Delhi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Brookhouser PE, Worthington DW, Kelly WJ. Noise induced hearing loss in children. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:645–655. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulrich RF, Pinheiro ML. Temporary hearing losses in teenagers attending repeated rock-and-roll sessions. Acta Otolaryngol. 1974;77:51–55. doi: 10.3109/00016487409124597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee PC, Senders CW, Gantz BJ, Otto SR. Transient sensorineural hearing loss after overuse of portable headphone cassette radios. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93:622–625. doi: 10.1177/019459988509300510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Razdan U, Sidhu TS. Need for research on health hazards due to noise pollution in metropolitan India. J Indian Med Assoc. 2000;98(8):453–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Consensus Conference Noise and hearing loss. JAMA. 1990;263(23):3185–3190. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440230081038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niskar AS, Kieszak SM, Holmes AE, et al. Estimated prevalence of noise-induced hearing threshold shifts among children 6 to 19 years of age: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994, United States. Pediatrics. 2001;108:40–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryberg J (2009) A national project to evaluate and reduce high sound pressure levels from music. Noise Health 11(i43):124 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Danhauer JL, Johnson CE, Byrd A, DeGood L, Meuel C, Pecile A, Koch LL (2009) Survey of college students on iPod use and hearing health. J Am Acad Audiol 20(1):5–27; quiz 83–4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kahari K, Aslund T, Olsson J. Preferred sound levels of portable music players and listening habits among adults: a field study. Noise Health. 2011;13(50):9–15. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.73994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogel I, Brug J, Van der Ploeg CP, Raat H (2011) Adolescents risky MP3-player listening and its psychosocial correlates. Health Educ Res 26(2):254–264 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kumar A, Kuruvilla M, Alexander SA, Kiran C. Output sound pressure levels of personal music systems and their effect on hearing. Noise Health. 2009;11:132–140. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.53357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rekha T, Unnikrishnan B, Mithra P, Kumar N, Bukelo M, Ballala K. Perceptions and practices regarding use of personal listening devices among medical students in coastal South India. Noise Health. 2011;13(4):329–332. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.85500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogel I, Verschuure H, van der Ploeg CP, Brug J, Raat H. Adolescents and MP3 players: too many risks, too few precautions. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):e953–e958. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biassoni EC, Serra MR, Richter U, et al. Recreational noise exposure and its effects on the hearing of adolescents. Part II: development of hearing disorders. Int J Audiol. 2005;44:74–86. doi: 10.1080/14992020500031728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cassandro E, Chiarella G, Catalano M, et al. Changes in clinical and instrumental vestibular parameters following acute exposition to auditory stress. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2003;23(4):251–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bohlin MC, Erlandsson SI. Risk behaviour and noise exposure among adolescents. Noise Health. 2007;9(36):55–63. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.36981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mostafapour SP, Lahargoue K, Gates GA. Noise induced hearing loss in young adults: the role of personal listening devices and other sources of leisure noise. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:1832–1839. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199812000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torre P., 3rd Young adults’ use and output level settings of personal music systems. Ear Hear. 2008;29(5):791–799. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31817e7409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrescu N. Loud music listening. Mcgill J Med. 2008;11(2):169–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosanowski F, Eysholdt U, Hoppe U (2006) Influence of leisure-time noise on outer hair cell activity in medical students. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 80(1):25–31 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Williams W, Beach E, Gilliver M. Clubbing (2010) The cumulative effect of noise exposure from attendance at dance clubs and night clubs on whole-of-life noise exposure. Noise Health 12(i48):155 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Serra MR, Biassoni EC, Richter U, et al. Recreational noise exposure and its effects on the hearing of adolescents. Part I: an interdisciplinary long term study. Int J Audiol. 2005;44:65–73. doi: 10.1080/14992020400030010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bogoch II, House RA, Kudla I. Perceptions about hearing protection and noise-induced hearing loss of attendees of rock concerts. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(1):69–72. doi: 10.1007/BF03404022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Widen SE, Erlandsson SI. Self-reported tinnitus and noise sensitivity among adolescents in Sweden. Noise Health. 2004;7(25):29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]