Abstract

Self-identification with ethnic-specific labels may indicate successful ethnic identity formation, which could protect against substance use. Alternatively, it might indicate affiliation with oppositional subcultures, a potential risk factor. This study examined longitudinal associations between ethnic labels and substance use among 1,575 Hispanic adolescents in Los Angeles. Adolescents who identified as Cholo or La Raza in 9th grade were at increased risk of past-month substance use in 11th grade. Associations were similar across gender and were not confounded by socioeconomic status, ethnic identity development, acculturation, or language use. Targeted prevention interventions for adolescents who identify with these subcultures may be warranted.

Keywords: culture, ethnicity, hispanic, latino, ethnic identity, tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, adolescents

Hispanics and Hispanic communities in the United States are at a disadvantage with regard to numerous public health and social problems including use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs, poverty, low educational attainment, depression, and HIV/AIDS (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012; Prado, Szapocznik, Maldonado-Molino, Schwartz, & Pantin, 2003). Hispanics represent the largest racial/ethnic minority group in the United States; they comprise 16.3% of the total population and are projected to comprise 30% of the total population by 2050 (Rumbaut, 2011). The Hispanic population in the United States is relatively young, with nearly 40% under 21 years of age (Marotta & Garcia, 2003; Ramírez & de la Cruz, 2003). Because Hispanic adolescents are at increased risk of early tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use relative to non-Hispanic White and African American adolescents (Johnston et al., 2012; Szapocznik, Prado, Burlew, Williams, & Santisteban, 2007), the future health and well-being of the Hispanic American population warrants immediate concern and attention (Prado et al., 2003).

Far from a monolithic group, “Hispanics” include individuals from a variety of national and cultural backgrounds, and they express varied ethnic and subcultural Hispanic identities (Holley et al., 2009). The extent and quality of their interactions with both their cultures of origin and the U.S. culture, and the cultural identities they adopt personally, may influence their decisions about engaging in health-promoting and health-compromising behaviors (Guzman, Santiago-Rivera, & Hasse, 2005; Marcell, 1994; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2001). Indeed, research reveals significant variation in adolescent substance use across national subgroups such as Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, Cuban Americans, and Salvadoran Americans (Delva et al., 2005; Prado et al., 2009; Vaeth, Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, & Rodriguez, 2009) and among first-, second-, and third-generation Hispanic Americans (Eitle, Wahl, & Aranda, 2009), as well as associations between substance use and acculturation (Bethel & Schenker, 2005; Castro, Stein, & Bentler, 2009; De La Rosa, 2002; Eitle et al., 2009; Marsiglia, Kulis, Hussaini, Nieri, & Becerra, 2010; Unger et al., 2000; Zamboanga, Schwartz, Jarvis, & Van Tyne, 2009).

Ethnic identity (Phinney, 1996) is the subjective sense of being a member of an ethnic group. Ethnic identity formation typically occurs throughout adolescence and young adulthood, through a process of examining the implications of being a member of various groups and finally deciding on a group (or multiple groups) with which to identify. Individuals who have thoroughly examined and resolved their ethnic identity are generally knowledgeable about their culture, have a subjective sense of belonging to that culture, label themselves as members of that culture, affiliate with other members of that culture, and participate in its traditions (Marsiglia, Kulis, & Hecht, 2001). The literature on ethnic identity (Phinney, 1992; 1996) proposes that having a well-examined ethnic identity can be a source of strength for youth because ethnic pride can protect against the damaging effects of negative stereotypes and discrimination. Previous research has indicated that a strong ethnic identity, including strong ethnic affiliation, attachment, and pride, may be protective against substance use (Brook, Zhang, Finch, & Brook, 2010; Love, Yin, Codina, & Zapata, 2006; Marsiglia, Kulis, Hecht, & Sills, 2004). However, other studies (Zamboanga, 2009) have identified ethnic identity as a risk factor for substance use, and some studies (Kulis, Marsiglia, Kopak, Olmsted, & Crossman, 2012) have found that the association between ethnic identity and substance use differs by gender and length of time in the United States.

Ethnic identity is more complex than national origin, generation in the United States, acculturation, and level of ethnic identity formation. The articulation of ethnic identity is complex and involves national origin, generation in the United States, acculturation, and level of ethnic identity formation. Independent of these factors, Hispanics may choose one or more labels to describe themselves, including pan-ethnic labels (e.g. Hispanic and Latino), national labels (e.g. Mexican, Mexican American, and Guatemalan), racial labels (e.g. White and indigenous), political labels (e.g., Chicano), and/or subcultural labels (e.g., Cholo and paisa) (Marcell, 1994). Although some of these labels are derogatory, members of marginalized groups often reclaim and use these labels as an act of resistance. The ethnic labels that people select to describe themselves may provide important information about their ethnic identity, values, relationship with the culture of origin and with the host culture (Bettie, 2000; Fuqua et al., 2012; Matute-Bianchi, 1986), just as the noncultural labels adopted by many adolescents (e.g. jock, brain, popular) express their interests, values, and social norms (Sussman, Pokhrel, Ashmore, & Brown, 2007). In this article, we focus on Hispanic subcultural labels including Cholo, Chicano, and La Raza. The identity labels chosen by the participants in this study have varied sociopolitical histories, as described in detail below.

Hispanic—often associated with an assimilationist model—emphasizes the Spanish colonial legacy of Latin America but is not indigenous to Latin American societies (Hayes-Bautista, 2004). In the United States, Hispanic has become a catch-all term for people from Mexico, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. Differences among Hispanics, however, remain salient to divergent groups whose colonial histories and sociopolitical and economic relations to the United States vary widely. Some groups have historically embraced the Spanish legacy of their identities, while others, especially those from less privileged backgrounds, try to distance themselves from the legacy of Spanish colonization (Delgado, 1998; Hidalgo, 2011; Rinderle, 2005; Rodriguez, 1998).

Mexican American often denotes people of Mexican origin who were born in the United States (Mahiri, 1998). We include the Mexican American ethnic label in this study because a large proportion of Hispanic/Latinos in Southern California are immigrants from Mexico or descendants of Mexican immigrants. However, a Mexican-American identity “[is] not a fixed set of customs surviving from life in Mexico, but rather a collective identity that emerged from the daily experience in the United States” (Sanchez, 1995). The Mexican American culture in the United States is an example of ethnogenesis—a culture that evolved from the blending of two cultures but is distinct from both of the original cultures (Flannery, Reise, & Yu, 2001). A Mexican American identify includes a historical sense of connection with Mexico but also acknowledges the deportation and repatriation campaigns against Mexican immigrants and their children during the 20th century that caused some Mexican-origin groups in the southwestern U.S. to become politicized around racial and ethnic inequality (Sanchez, 1995).

Chicano. The politicization of race and ethnicity spurred by the civil rights activism of the 1960s and 1970s gave rise to large numbers of Mexican-Americans, most notably in the southwest, who began to identify as Chicano/a (Beltran, 2004; Rinderle, 2005). A Chicano identity is less assimilationist than a Hispanic or even Mexican-American identity because it is rooted in a tradition of fighting for racial and ethnic equality. That said, however, prior to the 1960s, many poor and working class Mexicans used the term as a form of resistance to its use as a derogatory racial/ethnic slur levied against Mexicans by the dominant culture or by Mexican Americans with more economic resources (Acuña, 1996). Nearly half a century after the height of the Chicano Movement, Chicano organizations have become institutionalized and still fight for immigration reform and other issues that affect Hispanic/Latinos.

La Raza. Similar to the Chicano identity, the Raza identity emerged from the history of political, economic, and social disenfranchisement of Mexicans in the United States and their subsequent social activism (Gutierrez, 1995; Ochoa, 2004; Orozco, 2009). The term was originally used to assert that the blend of Native American and European cultures had produced a powerful and even superior raza cosmica (cosmic race) (Vasconcelos, 1997). The 1960s Chicano movement embraced a politicized Raza identity that emphasized the indigenous components of their heritage and de-emphasized European components (Oropeza, 2005). In recent decades, the term Raza has become more inclusive, reflecting the fact that Hispanic/Latinos are a mixture of many of the world’s races, cultures, and religions (Vasconcelos, 1997). The history of sociopolitical protest embedded in the term, however, remains salient for many who identify as Raza.

Cholo is a term used to describe gang members and people who affiliate with or admire gang members (Vigil, 1988). A qualitative study of high school students and teachers (Matute-Bianchi, 1986) described cholos as marginalized from school, oppositional, and denigrated or feared by other students because of their possible gang involvement. A study of 7th grade students in Southern California (Fuqua et al., 2012) found that students who self-identified as cholos (even though they were probably too young to have been active gang members) were more likely to smoke cigarettes, relative to those who identified with other groups such as jocks, popular kids, smart kids, skaters, etc.

Chicano, La Raza, and Cholo are examples of oppositional ethnic identities—identities that denote resistance to subjugation and discrimination by a dominant group (Ogbu, 1987). Youth whose opportunities are limited by social inequality may elect to adopt and enact oppositional identities embedded in suspicion, distrust, and rejection of dominant institutions and cultural ideals of “appropriate” behavior (Guzman et al., 2005; Ogbu, 1987). These youth often express disinterest in academic success and engage in rebellious or delinquent behavior (Ogbu, 1987). Unfortunately, youth who adopt such a stance inadvertently set themselves up for less success since, by rejecting school, for instance, students experience a decreased understanding of the reward structure of U.S. institutions (Reyes & Valencia, 1995; Valenzuela, 1999).

Overall, the theoretical and empirical literature on ethnic identity and substance use suggests two competing hypotheses. On one hand, identification with a specific subcultural group may be protective against substance use, because it may indicate a more examined and well-formed ethnic identity, which should serve as a buffer against discrimination and other risk factors for substance use (Phinney, 1996). On the other hand, identification with ethnic subcultural groups may be a risk factor for substance use because it may indicate identification with an oppositional identity, which could promote rebellious behaviors that are not accepted by mainstream society (Ogbu, 1987). This study examines the relationship between the articulation of various Hispanic ethnic subcultural group identities and tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use among Hispanic adolescents in the Los Angeles area.

METHODS

Project RED (Reteniendo y Entendiendo Diversidad para Salud) is a longitudinal study of acculturation patterns and substance use among Hispanic/Latino adolescents in Southern California. The respondents in this study were students attending seven high schools in the Los Angeles area who completed surveys in 9th, 10th, and 11th grade. Because this is a study of Hispanic adolescents, schools were approached and invited to participate if they contained at least 70% Hispanic students, as indicated by data from the California Board of Education, and were not participating in other studies or interventions designed to address variables of interest in this study. Efforts were also made to obtain a sample of schools with a wide range of socioeconomic characteristics. The median annual house-hold incomes in the ZIP codes served by the schools ranged from $29,000 to $73,000, according to 2000 U.S. Census data. Approval was obtained from the school principals and/or district superintendents, according to their established procedures.

Student Recruitment

The 9th, 10th, and 11th grade surveys were conducted in the Fall of 2005, 2006, and 2007, respectively. In 2005, all 9th-grade students in the school were invited to participate in the survey. Trained research assistants visited the students’ classrooms, explained the study, and distributed consent forms for the students to take home for their parents to sign. If students did not return the consent forms, the research assistants telephoned their parents to ask for verbal parental consent. Students with written or verbal parental consent were allowed to participate. Although the students were minors and could not give legal consent, we also gave them the opportunity to assent or decline to participate, as a way of involving them in the decision-making process. This procedure was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Across the seven schools, 3,218 students were invited to participate. Of those, 2,420 (75%) provided parental consent and student assent, and 2,222 (69%) completed the 9th grade survey. Of the 2,222 students who completed the 9th grade survey, 1,963 (88%) self-identified as Hispanic, Latino, Mexican, Mexican-American, Central American, South American, Chicano, Mestizo, La Raza, Cholo, or Spanish or reported a Latin American country of origin. Of those 1,963 Hispanic/Latino students, 1,575 (80%) also completed the 11th grade survey and provided complete data on all variables of interest. These 1,575 students are included in this analysis.

Survey Procedure

On the day of the survey, the data collectors distributed surveys to all students who had provided parental consent and student assent. Using a standardized script, they reminded the students that their responses were confidential and that they could skip any questions they did not want to answer. The classroom teachers were present during survey administration, but the data collectors instructed them not to participate in the survey process to ensure that they would not inadvertently see the students’ responses. To help students with low literacy skills, the data collectors also read the entire survey aloud during the class period so the students could follow along.

The data collectors returned to the schools when the students were in 10th and 11th grade. Students who could be located in the same schools (and students who had transferred to another school participating in the study) completed follow-up surveys in their classrooms, using the same procedure used in 9th grade. Extensive tracking procedures were used to locate the students who had transferred schools. For the 9th grade survey, students filled out a Student Information Sheet with contact information such as their home addresses, home phone numbers, cell phone numbers, parents’ cell phone numbers, email addresses, and addresses and phone numbers of a relative or close family friend who would know their whereabouts if they moved. School personnel also provided forwarding information if available. Data collectors telephoned the missing students in the evenings and surveyed them by telephone.

Measures

Surveys were available in English and Spanish. To create the Spanish translations, we first looked for the translated items that were published or recommended by the scales’ authors. If none were available, one translator translated the items from English to Spanish, and then the translation was checked by a translation team including bilingual researchers of Mexican, Salvadoran, and Argentinean descent. This procedure was used to ensure that the Spanish translation reflected the idioms that are used among Mexican-Americans and other Hispanic/Latinos living in Southern California. Although English and Spanish versions were available, only 17 students (0.8%) chose to complete the survey in Spanish. The survey assessed substance use, acculturation, family and peer characteristics, psychological variables, and demographic characteristics.

Ethnic Labels

The measurement of ethnic labels consisted of the stem, “Do you call yourself … .” followed by a list of ethnic labels. Each label could be marked “yes”, “no,” or “don’t know”. The list included the following: American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian, Black, or African American; Hispanic, Latino, or Latina; Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; White, Mexican, Central American, South American, Mexican-American, Chicano, or Chicana; and Mestizo, La Raza, Spanish, and Cholo. Respondents could choose more than one ethnic label. The list was derived from formative research done with a similar sample in preparation for this survey, during which adolescents were asked to list the terms they use for their racial, ethnic, and cultural groups.

Adolescents’ Acculturation

Adolescents responded to 12 items from the Revised Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans (ARSMA-II; Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995): seven from the Anglo orientation subscale and five from the Hispanic orientation subscale. These 12 items were selected on the basis of a pilot study in a similar school (Unger, unpublished), in which these items had the highest factor loadings on their respective scales. Recently, a shorter version of the ARSMA-II was validated among adolescents (Bauman, 2005). Unfortunately, this scale had not yet been published at the time when this survey was conducted. Of the 12 items we selected for our scale, 10 were also included in Bauman’s scale; Bauman included two items that we did not include (enjoying reading in Spanish and enjoying English movies), and we included two items that Bauman did not include (enjoying English music and enjoying reading in English). The remaining 10 items were identical across the two scales (enjoying Spanish language TV, enjoying speaking Spanish, enjoying Spanish movies, speaking Spanish, thinking in Spanish, speaking English, writing letters in English, associating with Anglos, thinking in English, and having Anglo friends). The scores on each subscale (U.S. Orientation and Hispanic Orientation) were rescaled so that they ranged from 0 = lowest to 1 = highest. The wording of the response options was not changed. The Cronbach’s alphas were .77 for U.S. Orientation and .88 for Hispanic Orientation.

Ethnic identity development was assessed with the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (Phinney, 1992). This 12-item scale has shown good reliability among adolescents and adults of diverse ethnic backgrounds, with Cronbach’s alphas typically above .80. In our sample, the Cronbach’s alpha was .88. Examples of items include, “I have spent time trying to find out more about my ethnic group, such as its history, traditions, and customs” and “I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means for me.”

Substance Use

Past-month cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use were the outcome measures. Respondents were asked, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?” “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol?” “In the last 30 days, how many times have you used marijuana (grass, pot, weed)?” The questions about the number of days in the past month were rated on a 7-point scale from “0 days” to “all 30 days.” The question about the number of times the respondent used marijuana was rated on a 6-point scale from “0 times” to “40 or more times.” All three substance use variables were log-transformed because their distributions were skewed.

Demographic characteristics included age, gender, and socioeconomic status (a composite variable based on the adolescents’ reports of their parents’ education, rooms per person in the home, eligibility for free or reduced price school lunch, and homeownership, and U.S. Census data on the median income in the respondent’s zip code) (Myers & Choi, 1992; Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2009).

Statistical Analysis

Multilevel logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between 9th grade predictors and 11th grade substance use. SAS PROC GLIMMIX was used with school as a random effect to control for the clustering of students within school. Because students could select more than one ethnic label, each label was included in the models as a separate dichotomous variable (1 checked, 0 = not checked). Age, gender, SES, ethnic identity = development, U.S. and Hispanic acculturation, and English language usage were included as covariates to control for confounding.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

As shown in Table 1, the students’ mean age in 9th grade was 14.0 years and the sample was approximately half male and half female. Because students self-reported their race/ethnicity with a “check all that apply” question, some selected multiple categories. Some of the Hispanic/Latino youth also self-reported as White (5%), African-American (1%), American Indian (1%), Asian (1%), or Pacific Islander (1%). Their countries of origin included Mexico (84%), the United States (29%), El Salvador (9%), Guatemala (6%), and Honduras (1%) (respondents could select more than one country of origin). Well over half of the students (62%) were second-generation (student born in the U.S. but neither parent born in the U.S.). The ethnic labels endorsed most frequently were Mexican-American (56%), Mexican (53%), Hispanic (50%), Latino/a (48%), Chicano/a (18%), Spanish (18%), Cholo/a (16%), La Raza (6%), Central American (4%), South American (2%), and Mestizo (1%). In 9th grade, past-month prevalence of substance use was 6% for cigarettes, 24% for alcohol, and 11% for marijuana. By 11th grade, past-month substance use had increased to 8% for cigarettes, 40% for alcohol, and 17% for marijuana.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of Hispanic/Latino students in 9th grade

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 12–13 | 123 | 8% |

| 14 | 1338 | 85% |

| 15–16 | 112 | 7% |

| Missing | 2 | 0% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 839 | 53% |

| Male | 728 | 46% |

| Missing | 8 | 1% |

| Generation in the United States | ||

| 1 (Student and parents born outside U.S.) |

214 | 14% |

| 2 (Student born in U.S., both parents born outside U.S.) |

978 | 62% |

| 3 (Student and at least one parent born in U.S.) |

364 | 23% |

| Other/missing | 19 | 1% |

| Ethnic label(s) endorsed | ||

| Mexican-American | 882 | 56% |

| Mexican | 835 | 53% |

| Hispanic | 788 | 50% |

| Latino/a | 756 | 48% |

| Chicano/a | 284 | 18% |

| Spanish | 283 | 18% |

| Cholo/a | 252 | 16% |

| La Raza | 95 | 6% |

| Central American | 63 | 4% |

| South American | 32 | 2% |

| Mestizo | 158 | 1% |

Attrition Analysis

To determine potential attrition bias, the participants who were followed through 11th grade (N = 1,575) were compared with those who were lost to follow-up (N = 388). The adolescents who were lost to attrition were more likely to self-identify as Cholos (28% vs. 16%, chi-square = 29.17, p < .0001). There were no differences between the students who were followed and those lost to attrition on probability of self-identifying as La Raza (8% vs. 6%, ns) or Chicano (17.5% vs. 18%, ns). The adolescents who were lost to attrition were slightly older than those who were followed successfully (14.1 vs. 14.0 years, t 2.64, p < .05), had significantly lower ethnic identity development scores (t = 2.38, p < .05) and lower Hispanic acculturation scores (t = 3.07, p <.005). However, those lost to attrition did not differ significantly from those followed successfully on gender, U.S. acculturation, or English language usage.

Associations Between Ethnic Labels and Substance Use

Table 2 shows the odds ratios for substance use in 11th grade. All odds ratios are adjusted for age, gender, SES, ethnic identity development, U.S. and Hispanic acculturation, and English language usage. Students who labeled themselves “Cholo/a” in 9th grade were at increased risk of using cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana in 11th grade. Students who labeled themselves “La Raza” in 9th grade were at increased risk of using cigarettes and marijuana in 11th grade. Students who labeled themselves “Spanish” were at lower risk of using alcohol in 11th grade. None of the other ethnic labels were independent predictors of substance use after controlling for the covariates.

TABLE 2.

Associations between self-identification in 9th grade and substance use in 11th grade among Hispanic/Latino adolescents

| Cigarettes | Alcohol | Marijuana | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.09(0.67–1.77) | 0.88(0.65–1.17) | 0.94(0.66–1.32) |

| Female gender | 0.50(0.33–0.75) | 0.82(0.65–1.04) | 0.61(0.46–0.81) |

| SES | 0.82(0.58–1.16) | 1 .05(0.86–1 .28) | 0.91(0.72–1.15) |

| Ethnic identity | 0.85(0.58–1.24) | 0.93(0.74–1.16) | 1.03(0.79–1.33) |

| U.S. Acculturation | 0.82(0.19–3.61) | 0.99(0.40–2.47) | 0.60(0.21–1.69) |

| Hispanic Acculturation | 0.28(0.08–1.07) | 0.93(0.43–2.02) | 0.55(0.22–1.37) |

| English language usage | 1.11(0.77–1.60) | 0.85(0.68–1.05) | 0.73(0.56–0.94) |

| Hispanic | 0.90(0.57–1.43) | 1.05(0.81–1.36) | 1.03(0.75–1.40) |

| Latino/a | 0.86(0.54–1.37) | 1.01(0.77–1.31) | 0.91(0.66–1.26) |

| Mexican | 0.81(0.52–1.25) | 1.15(0.89–1.48) | 1.13(0.84–1.52) |

| Central American | 1.10(0.41–2.95) | 0.57(0.31–1.06) | 0.81(0.40–1.65) |

| South American | 0.85(0.19–3.89) | 0.88(0.36–2.18) | 0.92(0.34–2.48) |

| Mexican-American | 1.08(0.71–1.65) | 1.10(0.86–1.41) | 0.94(0.71–1.25) |

| Chicano/a | 1.27(0.72–2.26) | 1.30(0.92–1.83) | 1.13(0.76–1.68) |

| Mestizo | 2.24(0.44–11.26) | 1.38(0.40–4.69) | 1.23(0.33–4.56) |

| La Raza | 2.30(1.11–4.75) | 1.61(0.95–2.73) | 1.82(1.06–3.12) |

| Spanish | 1.25(0.74–2.11) | 0.72(0.53–0.99) | 1.10(0.76–1.59) |

| Cholo/a | 2.03(1.26–3.27) | 2.14(1.55–2.96) | 1.51(1.07–2.12) |

Note: Odd ratios in boldface are significant at p < 0.05.

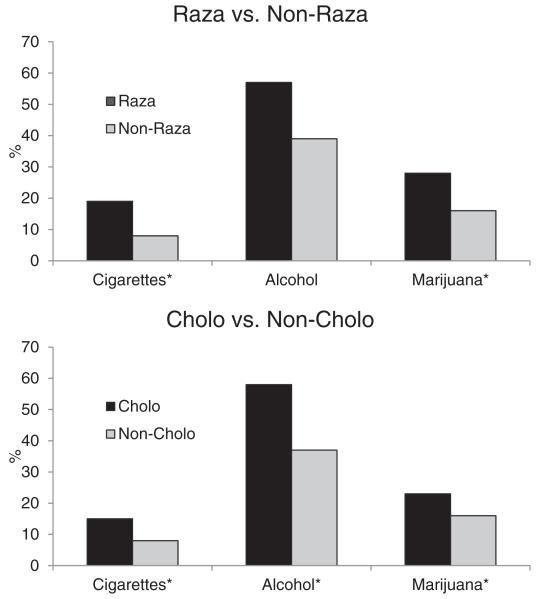

Figure 1 shows the proportion of respondents who reported past-month use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana, according to their ethnic labels. Raza youth had a significantly higher prevalence of use of all substances than non-Raza youth, and Cholo youth had a significantly higher prevalence of use of all substances than non-Cholo youth.

FIGURE 1.

Past-month substance in 11th grade according to ethnic labels. *p < .05.

Gender Interactions

To determine whether the associations between ethnic labels and substance use differed across gender, we added ethnic label × gender interaction terms to the logistic regression models after the main effects. None of these interaction terms were significant.

DISCUSSION

This longitudinal study of Hispanic adolescents in Los Angeles found that those who identified with the ethnic labels Cholo and Raza were at increased risk for substance use 2 years later. Cholo and La Raza are terms occasionally used by young Hispanic adolescents as oppositional identities (Ogbu, 1987). Whereas Cholo refers to gangs and criminal behavior, which are inherently oppositional to the “mainstream” culture, the oppositional connotation of Raza is more nuanced. Raza emerged during the Chicano movement as a way to identify with one’s indigenous roots and distance oneself from European colonization. Both Cholo and Raza are forms of self-identity that are asserted by their members, rather than assigned by others, as a way of expressing opposition to the dominant culture. Suspicion and distrust of the dominant culture is rooted often in objective and perceived discrimination of minority groups by the dominant culture, which may occur at school as well as in the community (McCombes & Gay, 1988). Racism and xenophobia are institutionalized in the media, as well, where “images of Mexicanos, Mexican Americans, Latinos, Hispanics, and Chicanos offered up to the American public tend to stream together to form one image … menaces from the borderlands [who] are often depicted as lawless bandits, roaming the badlands of urban America, producing crime rates inconceivable to the civilized public” (Duncan-Andrade, 2005). Images of the violent cholo/a gang member are especially problematic and are strongly associated with social problems and underachievement in school (Duncan-Andrade, 2005).

If minority youth living in urban settings perceive their ethnic group to be discriminated against and devalued by mainstream society, they may develop ethnic identities that are “thick” (central to the self-concept and social activities) and oppositional (Ogbu, 1987), which ultimately weaken their connection to mainstream institutions and lead to a rejection of mainstream norms (Portes 2003; Portes & Rumbaut 2001). This identity development process—reactive formation (Portes & Rumbaut 2001; Rumbaut, 2005)—is mostly likely to occur in poor, urban areas where the contexts of reception are hostile (e.g. diminishing economic opportunity, anti-immigrant sentiment, and discrimination). However, as the results of this study indicate, not all Hispanic/Latino youth embrace an oppositional culture characterized by comparatively high rates of substance use. In fact, the majority of participants did not embrace oppositional cultures and did not engage in substance use.

While beyond the scope of this research, we speculate that the mechanisms through which these youth come to identify with these ethnic labels and their related substance use patterns involve two salient factors: perceived discrimination and peer group association. In addition to institutional forms of discrimination, everyday social interactions are also salient for self-perceptions because peoples’ identities are profoundly impacted by our perceptions of how we are viewed by others (Cooley, 1956). A recent study of national and ethnic identities among Latinos and Caucasians shows that European or white Americans continue to be seen as “more American,” especially by whites (Devos, Gavin, & Quintana, 2010). Asian Americans, African American, and Native Americans are also seen as being “less American” than those of European descent (Devos & Banaji, 2005; Devos & Ma, 2008).

The substance use patterns of youth who identify as Cholo or Raza in this study may be directly linked to the peer groups in which they are embedded. Numerous studies of adolescents have documented associations between the peer groups that adolescents join (or are recruited by) and their risk of engagement in problem behaviors including substance use (Decovic, Wissinkb, & Meijerb, 2004; Sussman et al., 2007). The attitudes, motivation, and rationalization for oppositional behavior such as substance use as well as the opportunities to engage in oppositional behavior are provided by high-risk peer groups (Dishion, Andrews, & Crosby, 1995; Sussman et al., 2007). The peer group associations of youth who label themselves Cholo and Raza may endorse and promote norms more permissive to substance use as well as provide the settings in which to participate in these behaviors. As discussed earlier, studies involving cholo youth suggest that cholos embrace an oppositional culture (Matute-Bianchi, 1986) and even when quite young (i.e., 7th grade) are more likely to smoke cigarettes (Fuqua et al., 2012). The processes through which Cholo and Raza youth come to associate with peer groups who embrace an oppositional culture and the mechanisms and pathways through which those peer groups adopt oppositional values and norms, including permissive views towards substance use, warrant further investigation.

Limitations

These findings are based on data from adolescents who remained in school at least until 11th grade. Higher-risk students, including those with severe substance use problems and those with very strong affiliations to oppositional ethnic identities, may have dropped out of school and were not included in this sample. Therefore, the results reported here are conservative; they demonstrate that even within a lower-risk sample of in-school youth, some students do identify with oppositional ethnic identities, and that identification may place them at higher risk for substance use.

These results are based on adolescents’ self-reports of their substance use, which may have been underreported. However, the respondents were assured that their surveys were completely confidential, and previous studies have found adolescents’ self-reports of substance use to be quite accurate under confidential survey conditions (Harrison & Hughes, 1997).

One might argue that identification with a label such as Cholo or Raza is merely a proxy for other phenomena that are associated with substance use, such as acculturation, ethnic identity formation, socioeconomic status, etc. However, the associations between ethnic labels and substance use persisted even after controlling for these potential confounders. This suggests that the act of selecting and identifying with a subcultural ethnic label confers an additional risk for substance use, over and above the risks identified in previous studies.

This study found an elevated risk for substance use among participants who labeled themselves Cholo or Raza, but not Chicano. Chicano is similar to Cholo and Raza in that it is asserted by its members rather than assigned by the dominant culture, and it is an expression of resistance to oppression by the dominant culture. Therefore, we expected Chicano identity to be a risk factor for substance use, similar to Cholo and Raza. However, it is important to keep in mind that the term Chicano became popular in the 1960s and 1970s, when these adolescents’ parents and grandparents were coming of age. If the respondents identified with the term Chicano as a larger family identity with their parents and grandparents, they may have been less likely to adopt it as an oppositional identity such as Cholo or Raza.

CONCLUSION

In this study of Hispanic adolescents in Los Angeles, those who identified as Cholo or Raza in 9th grade were at increased risk for tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use in 11th grade. The future health and well-being of those who identify as Cholo or Raza can be adversely affected by the decisions they make in adolescence. It is not our intention to pathologize youth who identify as Cholo or Raza or those who associate with them. Rather, this study is an initial step toward understanding how the substance use patterns of youth who identify as Cholo and Raza differ from Hispanic/Latino youth more generally. Understanding how the ethnic identity formation process of these youth relates to substance use could potentially benefit substance use prevention efforts aimed at Latinos in general, especially those who identify with subcultural groups including Cholo and Raza.

GLOSSARY

- Ethnic identity

The subjective sense of being a member of an ethnic group.

- Ethnic labels

Ethnicity-related terms that individuals choose to describe themselves.

- Hispanic

People from Mexico, Central and South America, and the Caribbean.

- Mexican American

People of Mexican origin who were born in the United States.

- Chicano

An ethnic identity that is less assimilationist and more politically focused than Hispanic or Mexican American.

- La Raza

An ethnic identity that emphasizes indigenous roots and de-emphasizes European contributions to culture.

- Cholo

A term used to describe gang members and people who affiliate with or admire gang members.

- Oppositional ethnic identities

Identities that denote resistance to subjugation and discrimination by a dominant group.

Biographies

Jennifer B. Unger, Ph.D. is a Professor of Preventive Medicine at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine. Her research focuses on the psychological, social, and cultural influences on substance use and other health-risk behaviors among culturally diverse youth. She is the Principal Investigator on a NIH-funded study of acculturation patterns and risk behaviors among Hispanic adolescents transitioning into emerging adulthood and the Co-Principal Investigator of a two-city study of acculturation patterns and substance use among recent-immigrant Hispanic adolescents. She is also involved in the development and evaluation of culturally-relevant fotonovelas and telenovelas for health education about various topics including secondhand smoke, depression, diabetes, and organ transplantation. She directs the Ph.D. program in Preventive Medicine/Health Behavior Research at USC and teaches a Research Methods course.

James P. Thing, Ph.D. is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Institute for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. He conducts research on sexual identity formation among gay and bisexual Mexican men. His current project, for which he is collaborating with Bienestar Human Services, uses surveys and in-depth interviews to investigate how familial dynamics and disclosure/nondisclosure of sexual identity affects mental health, sexual risk, and substance use among young Latino gay and bisexual men.

Daniel W. Soto is the project manager for three NIH funded longitudinal research studies that focus on Latino adolescent drug use, social networks, and acculturation. He earned his Master of Public Health (MPH) degree from the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine. Mr. Soto’s research focus has been in the area of acculturation, social networks, and adolescent health risk behaviors.

Dr. Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati is an Associate Professor in Preventive Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California (USC). She holds a joint appointment in the Department of Sociology. She teaches courses at the graduate and undergraduate levels in the Masters of Public Health Program and in Health Promotion. She also lectures and mentors students in the PhD program in Behavioral Research. She teaches PM 525 Culture and International Health, and is the Director of the Global Health Track in the MPH program. As such, every summer she takes a group of 15 to 20 students abroad to perform their public health practicum and research. She has overseen practicum activities in Malawi, Mexico, Spain, Geneva, Panama, China, and India. Her area of research focuses on finding innovative and culturally specific ways to correct health disparities and on the role of culture in health and illness behaviors cross culturally. She has been widely funded by NIH and developed innovative projects with other investigators. She is the Associate Director of a Center of Excellence for Minority Youth. She is also the PI for the only statewide laboratory for the development and testing of educational materials for tobacco control, with funding from the CA Dept. of Health Services (CTCP). She uses community based participatory methods in her work and works with a variety of networks, including lay health care workers (promotores de salud), local lead agencies, over 60 health departments, and schools at the community level. Much of her teaching and research focuses on health communication, investigating optimal ways to communicate health information in order to correct cancer health disparities. These include tobacco prevention, alcohol and other drug use, obesity prevention, and screening and early detection for women’s cancers. She has published widely and is a well-recognized leader in health disparities working directly with diverse communities at a grass roots level.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

REFERENCES

- Acuña R. Anything but Mexican: Chicanos in contemporary Los Angeles. Verson; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman S. The reliability and validity of the Brief Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II for children and adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2005;27:426–441. [Google Scholar]

- Bethel JW, Schenker MB. Acculturation and smoking patterns among Hispanics: A review. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2005;29(2):143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran C. Patrolling borders: Hybrids, hierarchies and the challenge of mestizaje. Political Research Quarterly. 2004;57:597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Bettie J. Women without class: chicas, cholas, trash, and the presence/absence of class identity. Signs. 2000;26:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Zhang C, Finch SJ, Brook DW. Adolescent pathways to adult smoking: ethnic identity, peer substance use, and antisocial behavior. American Journal on Addiction. 2010;19(2):178–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Stein JA, Bentler PM. Ethnic pride, traditional family values, and acculturation in early cigarette and alcohol use among Latino adolescents. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30(3-4):265–292. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0174-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley CH. Human nature and social order. Free Press; Glencoe, IL: 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:275–304. [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa M. Acculturation and Latino adolescents’ substance use: a research agenda for the future. Substance Use and Misuse. 2002;37(4):429–56. doi: 10.1081/ja-120002804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decovic MA, Wissinkb IB, Meijerb AM. The role of family and peer relations in adolescent antisocial behaviour: Comparison of four ethnic groups. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:497–514. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado FP. When the silenced speak: The textualization and complications of Latina/o identity. Western Journal of Communications. 1998;62(4):420–438. [Google Scholar]

- Delva J, Wallace JM, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. The epidemiology of alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine use among Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban American, and other Latin American eighth-grade students in the United States: 1991-2002. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:696–702. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos T, Banaji MR. American = White? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88(3):447–66. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos T, Gavin K, Quintana FJ. Say ‘adios’ to the American dream? The interpaly between ethnic and national identity among Latino and Caucasian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16(1):37–49. doi: 10.1037/a0015868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos T, Ma DS. Is Kate Winslet more American than Lucy Liu? The impact of construal processes on the implicit ascription of a national identity. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;47(Pt 2):191–215. doi: 10.1348/014466607X224521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Andrews DW, Crosby L. Antisocial boys and their friends in early adolescence: Relationship characteristics, quality, and interactional process. Child Development. 1995;66(1):139–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan-Andrade JMR. An examination of the sociopolitical history of Chicanos and its relationship to school performance. Urban Education. 2005;40:576–605. [Google Scholar]

- Eitle TM, Wahl AM, Aranda E. Immigrant generation, selective acculturation, and alcohol use among Latina/o adolescents. Social Science Research. 2009;38(3):732–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery WP, Reise SP, Yu J. A comparison of acculturation models. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1035–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua JL, Gallaher PE, Author JB, Trinidad DR, Sussman S, Ortega E, Johnson CA. Multiple peer group self-identification and adolescent tobacco use. Substance Use and Misuse. 2012;47(6):757–66. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.608959. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.608959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez DG. Walls and mirrors: Mexican-Americans, Mexican immigrants and the politics of identity. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán MR, Santiago-Rivera AL, Hasse RF. Understanding academic attitudes and achievement in Mexican-origin youths: Ethnic identity, other-group orientation, and fatalism. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2005;1(1):3–15. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison L, Hughes A. Introduction—the validity of self-reported drug use: improving the accuracy of survey estimates. NIDA Research Monographs. 1997;167:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes-Bautista DE. Nueva California. The University of California Press; Berkeley: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo MM. Doctoral dissertation. 2011. Schooling La Raza: A chicana/o cultural history of education, 1968-2008. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database. (3458059) [Google Scholar]

- Holley LC, Salas LM, Marsiglia FF, Yabiku ST, Fitzharris B, Jackson KF. Youths of Mexican descent of the southwest: Exploring differences in ethnic labels. Child Sch. 2009 Jan 1;31(1):15–26. doi: 10.1093/cs/31.1.15. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Volume I: Secondary school students. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2012. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2011. [Google Scholar]

- Love AS, Yin Z, Codina E, Zapata JT. Ethnic identity and risky health behaviors in school-age Mexican-American children. Psychological Reports. 2006;98(3):735–44. doi: 10.2466/pr0.98.3.735-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis SS, Marsiglia FF, Kopak AM, Olmsted ME, Crossman A. Ethnic identity and substance use among Mexican-heritage preadolescents: Moderator effects of gender and time in the United States. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2012;32(2):165–199. doi: 10.1177/0272431610384484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahiri J. Rewriting identity: Social meanings of literacy and “re-visions” of self. Reading Research Quarterly. 1998;33(4):416–433. [Google Scholar]

- Marcel AV. understanding ethnicity, identity, and risk behavior among adolescents of Mexican descent. The Journal of School Health. 1994;64(8):323–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1994.tb03321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marotta SA, Garcia JG. Latinos in the United States in 2000. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Science. 2003;25(1):13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Hecht ML. Ethnic labels and ethnic identity as predictors of drug use and drug exposure among middle school students in the Southwest. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Hecht ML, Sills S. Ethnicity and ethnic identity as predictors of drug norms and drug use among preadolescents in the US Southwest. Substance Use and Misuse. 2004;39(7):1061–94. doi: 10.1081/ja-120038030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Hussaini SK, Nieri TA, Becerra D. Gender differences in the effect of linguistic acculturation on substance use among Mexican-origin youth in the southwest United States. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2010;9(1):40–63. doi: 10.1080/15332640903539252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bianchi ME. Ethnic Identities and patterns of school successes and failure among Mexican-decent and Japanese-American students in a California High school: An ethnographic analysis. American Journal of Education. 1986;95:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- McCombes RC, Gay J. Effects of race, class, and IQ information on judgments of parochial grade school teachers. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1988;128:647–652. [Google Scholar]

- Myers D, Choi SY. Growth in overcrowded housing: a comparison of the states. Applied Demography. 1992;7:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa GL. Becoming neighbors in a Mexican American community: Power, conflict and solidarity. University of Texas Press; Austin: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Oropeza L. iRaza Si! iGuerra No!: Chicano protest and patriotism during the Vietnam War era. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco CE. No Mexicans, women or dogs allowed: The rise of the Mexican American civil rights movement. University of Texas Press; Austin: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu J. Variability in minority school performance: A problem in search of an explanation. Anthropology and Education Quarterly. 1987;18:312–334. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Understanding ethnic diversity: The role of ethnic identity. American Behavioral Scientist. 1996;40:143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. Ethnicities: Children of migrants in America. Development. 2003;46(3):42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut R. Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. University of California Press and Russell Sage Foundation; Berkeley, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Szapocznik J, Maldonado-Molino MM, Schwartz SJ, Pantin H. Drug use/abuse prevalence, etiology, prevention, and treatment in Hispanic adolescents: A cultural perspective. Journal of Drug Issues. 2003;38:5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Prado GJ, Schwartz SJ, Maldonado-Molina M, Huang S, Pantin HM, Lopez B, Szapocznik J. Ecodevelopmental × intrapersonal risk: substance use and sexual behavior in Hispanic adolescents. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(1):45–61. doi: 10.1177/1090198107311278. doi: 10.1177/1090198107311278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez RR, de la Cruz GP. The Hispanic population in the United States: March 2002 (Current Population Report P20-545) U.S. Census Bureau; Washington DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes P. l., Valencia RR. Education policy and the growing Latino student population: Problems and prospects. In: Padilla A, editor. Hispanic psychology. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 303–325. [Google Scholar]

- Rinderle S. The Mexican diaspora: A critical examination of signifiers. Journal of Communication Inquiry. 2005;29:294–316. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez JA. Becoming Latinos: Mexican Americans, chicanos, and the Spanish myth in the urban southwest. Western Historical Quarterly. 1998;29(2):165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. Turning points in the transition to adulthood: Determinants of educational attainment, incarceration, and early childbearing among children of immigrants. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2005;28:1041–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. Pigments of our imagination: The racialization of the Hispanic-Latino category. Migration Information Source. 2011 Sep 23rd; retrieved from www.migrationinformation.org.

- Sanchez GJ. Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, culture, and identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945. Oxford University Press; Oxford: [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Pokhrel P, Ashmore RD, Brown BB. Adolescent peer group identification and characteristics: a review of the literature. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(8):1602–27. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Prado G, Burlew AK, Williams RA, Santisteban DA. Drug abuse in African American and Hispanic adolescents: Culture, development, and behavior. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:77–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Fine MA. Methodological implications of grouping Latino adolescents into one collective ethnic group. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2001;23:347. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Cruz TB, Rohrbach LA, Ribisl KM, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Chen X, Trinidad DR, Johnson CA. English language use as a risk factor for smoking initiation among Hispanic and Asian American adolescents: Evidence for mediation by tobacco-related beliefs and social norms. Health Psychology. 2000;19(5):403–10. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.5.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Parent-child acculturation discrepancies as a risk factor for substance use among Hispanic adolescents in Southern California. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2009;11(3):149–157. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9083-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaeth PA, Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Rodriguez LA. Hispanic Americans Baseline Alcohol Survey (HABLAS): alcohol-related problems across Hispanic national groups. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(6):991–991. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valuenzuel A. Subtractive schooling: U.S. Mexican youth and the politics of caring. State University of New York; Albany: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos J. The Cosmic Race/La raza cosmic. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1997. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Vigil JD. Barrio gangs: Street life and identity in Southern California. University of Texas Press; Austin: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, Schwartz SJ, Jarvis LH, Van Tyne K. Acculturation and substance use among Hispanic early adolescents: Investigating the mediating roles of acculturative stress and self-esteem. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30(3-4):315–33. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0182-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]