Abstract

The development of wild-type, unmodified Type 3 Dearing strain reovirus as an anticancer agent has currently expanded to 32 clinical trials (both completed and ongoing) involving reovirus in the treatment of cancer. It has been more than 30 years since the potential of reovirus as an anticancer agent was first identified in studies that demonstrated the preferential replication of reovirus in transformed cell lines but not in normal cells. Later investigations have revealed the involvement of activated Ras signaling pathways (both upstream and downstream) and key steps of the reovirus infectious cycle in promoting preferential replication in cancer cells with reovirus-induced cancer cell death occurring through necrotic, apoptotic, and autophagic pathways. There is increasing evidence that reovirus-induced antitumor immunity involving both innate and adaptive responses also contributes to therapeutic efficacy though this discussion is beyond the scope of this article. Here, we review our current understanding of the mechanism of oncolysis contributing to the broad anticancer activity of reovirus. Further understanding of reovirus oncolysis is critical in enhancing the clinical development and efficacy of reovirus.

Keywords: reovirus, oncolysis, Ras, EGFR, PKR, apoptosis, necrosis, autophagy

Introduction

Reovirus structure

Reovirus is a member of the Reoviridae family of viruses whose name was coined in 1959 and derived from the fact that it is commonly isolated from the respiratory and enteric tract without an association with clinical symptoms, or an orphan virus, although infection can be associated with mild respiratory and enteric symptoms in humans (1–5). Antibody neutralization and hemagglutination-inhibition studies have identified three distinct serotypes of reovirus [Type 1 Lang, Type 2 Jones, Type 3 Abney, and Type 3 Dearing (T3D)] (1, 3, 5).

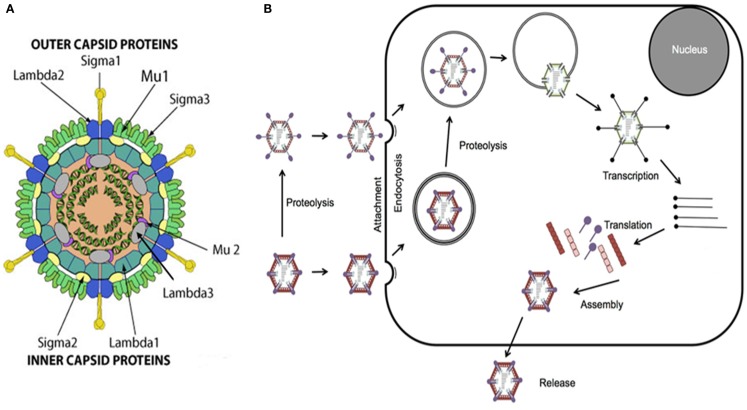

Reovirus is a non-enveloped double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) virus comprised of an outer and inner protein shell which altogether form a 20-sided icosahedral capsid (1, 2, 4, 6). The entire virus has an approximate diameter of 80 nm and houses its genome consisting of 10 segments of dsRNA that encode for structural and non-structural proteins involved in viral attachment, viral replication, virulence, and formation of viral inclusions (Figure 1) (1, 4, 7–10).

Figure 1.

Reovirus structure and infectious cycle. (A) Reovirus is a non-enveloped double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) virus approximately 80 nm in diameter. The viral genome, consisting of 10 segments of dsRNA, is contained within an outer and inner capsid and encodes for structural proteins comprising the outer capsid including sigma 1 (σ1), sigma 3 (σ3), lambda 2 (λ2), and mu 1 (μ1), structural proteins comprising the inner capsid including sigma 2 (σ2), lambda 1 (λ1), lambda 3 (λ3), and mu 2 (μ2), and non-structural proteins including sigma 1s (σ1s), sigma NS (σNS), mu NS (μNS), and mu NSC (μNSC). σ1 has been identified as the viral attachment protein, μ1, μ2, and λ3 serve roles in viral replication, σ1s and σ3 appear to have roles in virulence, and σNS, μNS, and μNSC appear to be involved in the formation of viral inclusions. Figure reproduced with permission from ViralZone, SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. (B) Viral attachment to host cell surface glycans results in internalization of reovirus via receptor-mediated endocytosis. Alternatively, infectious subvirion particles (ISVPs) can be formed from proteolysis by extracellular proteases allowing their direct entry into cells via membrane penetration. Once internalized, the virus is transported to early and late endosomes where it undergoes proteolytic disassembly and degradation resulting in the formation of ISVPs and subsequently in the release of transcriptionally active viral core particles into the cytoplasm. Activated RNA-dependent RNA polymerase begins primary transcription within the core particles resulting in the release of primary transcripts that, along with protein products of early translation, form complexes or inclusions where further transcription and translation occur which, in turn, ultimately lead to viral replication and assembly, host cell death, and progeny release.

Reovirus infectious cycle

The infectious life cycle of reovirus begins with attachment of viral protein sigma 1 (σ1) to target cell surface sialic acid residues, which have been shown to be α-linked 5-N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) and ganglioside GM2 glycan for serotypes T3D and Type 1 Lang, respectively (8, 11–13). Attachment to cell surface glycans facilitates binding to junctional adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A) which, in turn, results in internalization of reovirus via receptor beta 1 (β-1)-integrin mediated endocytosis (14, 15). Once internalized, the virus is transported to early and late endosomes where it undergoes proteolytic disassembly and degradation of the outer shell proteins sigma 3 (σ3) and mu 1 (μ1), in particular, by cysteine cathepsin proteases resulting in the formation of infectious subvirion particles (ISVPs) and ultimately in the release of transcriptionally active viral core particles, mediated by cleavage fragments of viral capsid proteins, into the cytoplasm (16–20). Of note, functional microtubules appear to be required, in part, for the process of endocytic sorting following internalization (21). ISVPs may also be formed from proteolysis by extracellular proteases, such as those in the gastrointestinal tract, allowing their direct entry into cells via membrane penetration (4, 22).

The viral core particles contain the necessary machinery including RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, guanylyltransferase, and methyltransferase to initiate viral replication (1, 2, 4–7). Activated RNA-dependent RNA polymerase begins primary transcription within the core particles resulting in the release of primary transcripts that, along with protein products of early translation, form complexes or inclusions where further transcription and translation occur which, in turn, ultimately lead to viral replication and assembly, host cell death, and progeny release (1, 2, 4–7). The events following virus internalization, endocytic processing, and viral core release remain poorly understood (Figure 1).

Mechanism of Oncolysis

Early investigations

The potential for wild-type reovirus as an anticancer agent was identified more than 30 years ago when studies demonstrated the preferential replication of reovirus in transformed cell lines but not in normal cells (23, 24). The mechanism of oncolysis by reovirus remained largely unknown until murine cell lines transfected with genes encoding the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) demonstrated increased susceptibility to reovirus infection (25).

Normally, ligand-binding to EGFR activates the tyrosine kinase activity of EGFR and results in the autophosphorylation of the receptor’s cytoplasmic domain leading to the recruitment of phosphotyrosine-binding adaptor molecules such as Shc and Grb2 (26). Grb2, with or without association with Shc, recruits the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) son of sevenless (SOS) to the plasma membrane where it activates the small G protein Ras by promoting the exchange of GTP for GDP on Ras and therefore converting it from an inactivated GDP-bound state to an activated GTP-bound state (Ras-GTP) (26). Ras-GTP can then subsequently activate numerous downstream signaling pathways involved in cellular differentiation and proliferation (26). An example of one such pathway, which has been well characterized, involves Ras-GTP association with Raf-1 that activates the kinase activity of Raf resulting in the phosphorylation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) called MEK1 and MEK2 (26). Activated MEKs, in turn, phosphorylate and activate extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERKs) that ultimately translocate to the nucleus and partake in a number of pathways involved in cellular processes including transformation (26).

Interestingly, cell lines naturally resistant to reovirus infection demonstrated enhanced susceptibility when transformed with the v-erbB oncogene, which encodes for a truncated form of the EGFR lacking the extracellular ligand-binding domain but possessing constitutive tyrosine kinase activity, suggesting that reovirus infection is facilitated by EGFR-mediated pathways rather than binding of the virus to EGFR itself (27). Activating Ras mutations have been associated with approximately 30% of all human cancers though this number likely underestimates the true prevalence of activated Ras pathways in cancer given that mutations upstream and downstream of the Ras signaling pathway have also been associated with cellular transformation (28, 29). Not surprisingly, subsequent studies investigated the facilitation of reovirus infection by activated downstream EGFR-mediated pathways and, in particular, the activated Ras signaling pathway to uncover potential relationships to the mechanism of selective oncolysis.

Activated Ras signaling pathway

Indeed, the downstream targets or intermediates to such pathways were elucidated when NIH-3T3 fibroblasts transfected with constitutively activated SOS or Ras oncogenes resulted in enhanced susceptibility to reovirus infection (30). Importantly, this finding occurred only in the presence of a zinc-inducible promoter, ZnSO4, which suggested that the activated Ras protein itself, rather than the effects of prolonged transformation, was sufficient to confer sensitivity to reovirus infection (30). Ras-GTP, however, is known to stimulate over more than 18 downstream effectors with the best characterized being the Raf kinases, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), and the GEFs for the small G protein Ral pathways (RalGEF) (29). Later studies aimed to narrow the list of potential downstream effectors of Ras important to reovirus oncolysis (31).

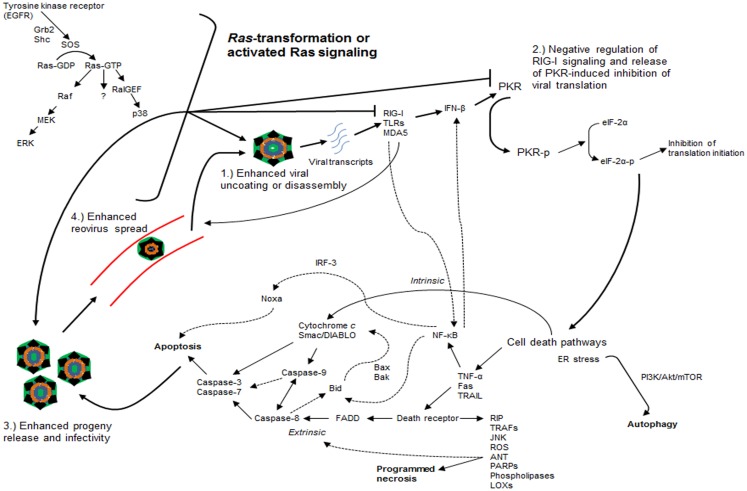

When Ras-transformed NIH-3T3 fibroblasts expressing mutations in the effector-binding domains of the Ras protein were used, reovirus replication was found to be independent of signaling through Raf or PI3K downstream pathways (31). Only the V12G37 mutant, which retained RalGEF signaling capability, rendered Ras-transformed cells susceptible to reovirus infection while the use of a dominant-negative mutant of Ral rendered transformed cells non-permissive to reovirus infection (31). Interestingly, an activated mutant of RalGEF, Rlf, permitted reovirus replication in the absence of an activating Ras mutation (31). Lastly, it was demonstrated that p38 kinase (a downstream effector of RalGEF), but not stress-activated c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase (JNK), plays a role in establishing reovirus infection (31). In short, these findings implicate the Ras/RalGEF/p38 pathway in the promotion of selective reovirus replication (Figure 2) (31).

Figure 2.

Ras-transformation affects several steps of the reovirus infectious cycle to promote oncolysis. Ras-transformation affects multiple steps of the infectious life cycle in promoting reovirus oncolysis by: (1) enhancing virus uncoating and disassembly, (2) negative regulation of retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) signaling and releasing dsRNA-activated protein kinase (PKR)-induced translational inhibition, (3) increasing progeny release through enhanced apoptosis and generating more infectious progeny, and (4) enhancing viral spread in subsequent rounds of infection. Reovirus-induced cancer cell death occurs through autophagic, apoptotic, and necrotic pathways. Programed necrosis or necroptosis occurs through binding of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), Fas ligand (Fas), and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) to death receptors leading to downstream signaling involving receptor interaction protein kinase (RIP) 1 and 3, cylindromatosis (CYLD), TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs), stress-activated c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase (JNK), reactive oxygen species (ROS), adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT), poly ADP-ribose polymerases (PARPs), phospholipases, and lipoxygenases (LOXs). Apoptosis occurs through both extrinsic [e.g., TRAIL binding to cell surface death receptor recruits Fas-associated death domain (FADD), which recruits and activates the initiator caspase-8 that ultimately activates effector caspases-3 and -7] and intrinsic pathways [cytochrome c and second mitochondrion-derived activator of caspase (Smac/DIABLO) release with activation of downstream effector caspases with or without caspase-9]. Autophagy occurs through endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated signaling. Dashed arrows represent putative cross-talk and suggested signaling pathways. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; SOS, son of sevenless; RalGEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for the small G protein Ral pathways; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase; ERK, extracellular signal regulated kinase; TLRs: toll-like receptors; MDA5, melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5; IFN-β, interferon-beta; eIF-2α, eukaryotic initiation factor 2α; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa light-chain enhancer of activated B cells; IRF-3, interferon regulatory factor 3.

Early evidence suggested that increased expression of reovirus proteins was observed in Ras-transformed cells and correlated with elevated virus titers, while relatively impaired expression was observed in untransformed cells (29, 30). In untransformed cells, the inhibition of translation appeared to be a key step in preventing reovirus replication given that reovirus demonstrated equivalent binding, entry, and primary transcription in both Ras-transformed and untransformed cells (30, 31). A separate study highlighted the potential inhibitory activity of the reovirus structural protein σ3 on the dsRNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) (32). As a result, the role of PKR in reovirus oncolysis was implicated in lieu of the above observations (29).

In the presence of viral infection, viral transcripts are recognized and bound by receptors including toll-like receptors (TLRs), retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) resulting in the activation of transcription factors such as nuclear factor kappa light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) (33, 34). These factors then induce the release of type I interferons [interferon-beta and -alpha (IFN-β and -α)] that upregulate the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), including the production of the serine/threonine kinase, PKR, involved in viral transcript degradation and inhibition of viral protein synthesis (33–35). PKR itself can bind to dsRNA resulting in dimerization, autophosphorylation, and activation (35). The same phenomenon has been observed in response to the presence of reovirus S1 mRNA as well (36). Activated PKR phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF-2α) rendering it inactive and thereby leading to the inhibition of protein synthesis and viral replication (35).

It was determined that PKR remained inactivated in Ras-transformed cells thereby establishing the link between an activated Ras signaling pathway and PKR in reovirus oncolysis (30). The link between Ras-transformed cells and PKR inactivation has previously been suggested, but the use of a specific inhibitor to PKR phosphorylation by Strong et al. (30) that restored reovirus translation in untransformed cells offered evidence to the direct role PKR plays in determining resistance to selective reovirus replication (30, 37). Later studies demonstrated that Ras-transformation, through the MEK/ERK pathway, enhanced reovirus spread in subsequent rounds of infection by suppressing viral transcript-induced interferon-beta (IFN-β) production through negative regulation of RIG-I signaling (33). Accordingly, knockdown of either RIG-I or PKR led to increased susceptibility of untransformed cells to reovirus infection (33). The exact mechanism behind the coordination of Ras-transformation and PKR-mediated promotion of viral replication is unclear, but it remains among the best characterized processes in the understanding of reovirus oncolysis.

The coordination between the activated Ras signaling pathway, RIG-I and interferon signaling pathways, and PKR in the promotion of reovirus translation represents one potential mechanism among several emerging concepts detailing the effects of Ras-transformation on the reovirus infectious cycle (33, 38, 39). Other steps of the infectious cycle appear to be affected by Ras-transformation and involved in reovirus oncolysis as well. For example, in contrast to reovirus infection-susceptible glioma cell lines and Ras-transformed NIH-3T3 fibroblasts, reovirus-resistant and untransformed cells demonstrated prohibition of viral disassembly or uncoating due to the lack of degradation of σ3 and cleavage of μ1 proteins indicative of ISVP formation (38). Interestingly, disassembly restrictive cells introduced to ISVPs (in vitro) or grown as a tumor (in vivo), where elevated levels of active cathepsin B and L were observed in tumors, demonstrated productive reovirus infection and highlighted the significance of reovirus uncoating to susceptibility to oncolysis (38). Indeed, Ras-transformation of fibroblastic cell lines is associated with increased levels of cathepsin proteases (40, 41).

A separate study corroborated these findings when Ras-transformed NIH-3T3 fibroblasts demonstrated a threefold enhancement in reovirus uncoating compared to untransformed cells (39). Importantly, reovirus particles purified from Ras-transformed cells were four times more infectious than those from untransformed cells, and progeny release, mediated by caspase-induced apoptosis, was nine times more efficient in Ras-transformed cells when compared to untransformed cells (39). Of note, reovirus-induced apoptosis appears to be regulated, in part, through JNK signaling though the complexities and host of mediators involved in apoptosis by reovirus will be discussed later (42).

Altogether, these studies highlight two important points regarding reovirus oncolysis: (1) although prior studies implicate the Ras/RalGEF/p38 pathway in the promotion of reovirus oncolysis independent of Raf and JNK signaling, MEK/ERK, and JNK appear to have roles in reovirus infectivity and reovirus-induced apoptosis, and (2) further understanding of the reovirus infectious cycle has demonstrated that Ras-transformation affects multiple steps of the cycle, in addition to viral translation, such as viral uncoating or disassembly, generation of viral progeny with enhanced infectivity, release of progeny through enhanced apoptosis, and viral spread in subsequent rounds of infection (Figure 2) (31, 33, 38–42).

Pathways of reovirus-induced cell death

There remains great debate in the pathway(s) by which reovirus induces cancer cell death. On one hand, intratumoral injections of reovirus into mouse xenograft models of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) induced tumor cell death through overwhelming burden of viral replication or cell lysis as evidenced by significant necrosis in the absence of apoptosis in pathologic specimens (43). Indeed, necrotic cell death appears to be a regulated process, more so than once believed, as programed necrosis or necroptosis is induced by binding of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), Fas ligand (FasL), and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) to death receptors leading to downstream signaling involving mediators such as receptor interaction protein kinase (RIP) 1 and 3, cylindromatosis (CYLD), TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs), JNK, reactive oxygen species (ROS), adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT), poly ADP-ribose polymerases (PARPs), phospholipases, and lipoxygenases (LOXs, Figure 2) (44–46).

On the other hand, apoptosis is a firmly established means of reovirus-induced cell death and has been demonstrated to be caspase-dependent and enhanced by activated Ras signaling (39, 47). Reovirus-induced apoptosis proceeds through both death receptor-associated (extrinsic) and mitochondrial-associated (intrinsic) pathways (48). For example, binding of the ligand TRAIL to the TNF superfamily of cell surface death receptors following reovirus infection recruits the adaptor molecule, Fas-associated death domain (FADD), which recruits and activates the initiator caspase-8 that ultimately activates effector caspases-3 and -7, forming part of the final common pathway for both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways (Figure 2) (48–50). In addition, following reovirus infection, the mitochondrial pro-apoptotic proteins cytochrome c and second mitochondrion-derived activator of caspase (Smac/DIABLO) are released, without disturbance of the mitochondrial membrane potential or release of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), and eventually activate downstream effector caspases with or without caspase-9 (caspase-9 is activated by cytochrome c but has been shown to be dispensable in the mitochondrial-associated pathway) (48, 51). There is a great degree of cross-talk between both apoptotic pathways, for example, activation of caspase-8 in the extrinsic pathway leads to the cleavage of the pro-apoptotic protein Bid and results in the release of cytochrome c and Smac/DIABLO (presumably through pro-apoptotic proteins Bax or Bak), activation of caspase-9, and eventual activation of effector caspases (Figure 2) (48, 51).

As previously suggested, viral uncoating or disassembly is critical for reovirus-induced apoptosis (52). Studies have identified several key components of the viral structure implicated in apoptosis including σ1, sigma 1s (σ1s), and μ1 in association with σ3 (53, 54). Ectopic expression of μ1 activated both extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways characterized by activation of initiator caspases-8 and -9, release of cytochrome c and Smac/DIABLO into the cytosol, and activation of downstream effector caspase-3 independent of the pro-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family members Bax and Bak (55).

The complexity of reovirus-induced apoptosis continues to grow (Figure 2). The roles of TRAIL, Bid, Bax, and Bak in reovirus-induced apoptosis have previously been discussed (48–51). As previously mentioned, JNK also regulates reovirus-induced cell death as activation of caspase-3 and apoptosis were inhibited by cells deficient with MEK kinase 1, an upstream activator of JNK (42). NF-κB also appears to play crucial roles in reovirus-induced apoptosis via stabilization of the tumor suppressor p53 and NF-κB-dependent mechanisms leading to Bid cleavage (56–58). Apoptosis by reovirus appears to require IRF-3 and NF-κB, in part, for efficient expression of the pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family, Noxa, independent of IFN-β induction (34). Reovirus appears to downregulate cellular FLICE inhibitory protein (cFLIP) and Akt activation to increase susceptibility to TRAIL-induced apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells and gastric cancer cells, respectively (59, 60). In neurons, reovirus-induced apoptosis is facilitated by upregulation of death-associated protein 6 (Daxx), an adaptor between the Fas death receptor and JNK signaling cascade, within the cytoplasm (61, 62). Moreover, apoptosis appears to be facilitated by reovirus-induced inhibition of microRNA-let-7d and upregulation of caspase-3 activity (63).

Alternatively, autophagy appears to be yet another mechanism of reovirus-induced cell death as reovirus infection of multiple myeloma cells demonstrated oncolysis mediated by both apoptotic and autophagic pathways (64, 65). Specifically, autophagy, as detected by Cyto-ID staining and vesicle colocalization with LC3-II (a marker of autophagosomes), was evident in human multiple myeloma cells (RPMI 8226) at 24 and 48 h of reovirus treatment (64). A fourfold reduction in autophagy by 48 h of reovirus infection was demonstrated when RPMI 8226 cells were pre-treated with the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA) (64). Understanding of the mechanisms behind mammalian reovirus-induced autophagy is limited to the above studies; however, in vitro studies involving avian reovirus (ARV) have provided further insight (66, 67). ARV infection of Vero cells in vitro induced autophagy via PI3K/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling detected by immunoblotting (67). Furthermore, pre-treatment of primary chicken fibroblasts and Vero cells with rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor known to induce autophagy, and chloroquine, an inhibitor of lysosome–autophagosome fusion and autophagy, resulted in increased and decreased viral production, respectively, in ARV-infected cells (67). Separate studies have highlighted that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress not rescuable by the unfolded protein response (UPR) has been shown to enhance autophagy via negative regulation of the Akt/tuberous sclerosis protein (TSC)/mTOR pathway (68). Interestingly, reovirus-mediated apoptosis of multiple myeloma cells is also characterized by the stimulation of ER stress along with induction of Noxa (69). Indeed, growing evidence suggests autophagy mediated by PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling and ER stress as a potential mechanism of reovirus-induced cancer cell death, although further investigation is warranted.

Lastly, it should be noted that reovirus-induced cell death in Ras-transformed cells is not absolute, but rather enhanced or more efficient relative to untransformed cells (29, 30, 39). The cytopathicity of reovirus infection in normal cells has long been characterized by respiratory and enteric pathogenicity in humans with seropositivity having been documented in as many as 70–100% of subjects (1–5). In clinical trials involving reovirus monotherapy in the treatment of cancer, common treatment-related adverse effects have included nausea, vomiting, fatigue, fever, myalgias, and other constitutional symptoms consistent with its relatively mild and benign viral pathophysiology in humans (1, 2, 4, 6, 7). The increased sensitivity for replication in cancer cells and excellent toxicity profile demonstrated in recent trials underscore the promising clinical potential of reovirus as an anticancer agent.

Conclusion

Reovirus is a dsRNA virus whose mechanism of oncolysis remains unclear though activated Ras signaling, involving upstream and downstream mediators, appears important to permissiveness to reovirus replication. In promoting oncolysis, Ras-transformation affects multiple steps of the infectious life cycle including viral uncoating and disassembly, releasing PKR-induced translational inhibition, generation of viral progeny, release of progeny, and viral spread with reovirus-induced cancer cell death occurring through necrotic, apoptotic, and autophagic pathways. However, several studies have highlighted that reovirus oncolysis occurs independent of activated EGFR and Ras signaling pathways, while others have linked reovirus oncolysis to cell cycle phase (70–72). Undoubtedly, despite our progress in understanding reovirus oncolysis, further investigation into the mechanism of preferential replication in cancer cells is still warranted to enhance the antitumor efficacy of reovirus whose development has currently expanded to 32 clinical trials (both ongoing and completed) in the treatment of cancer.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Vidal L, Yap TA, White CL, Twigger K, Hingorani M, Agrawal V, et al. Reovirus and other oncolytic viruses for the targeted treatment of cancer. Target Oncol (2006) 1:130–50 10.1007/s11523-006-0026-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comins C, Heinemann L, Harrington K, Melcher A, De Bono J, Pandha H. Reovirus: viral therapy for cancer ‘as nature intended’. Clin Oncol (2008) 20:548–54 10.1016/j.clon.2008.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norman KL, Lee PW. Reovirus as a novel oncolytic agent. J Clin Invest (2000) 105:1035–8 10.1172/JCI9871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly K, Nawrocki S, Mita A, Coffey M, Giles FJ, Mita M. Reovirus-based therapy for cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther (2009) 9:817–30 10.1517/14712590903002039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norman KL, Lee PW. Not all viruses are bad guys: the case for reovirus in cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today (2005) 10:847–55 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03483-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrington KJ, Vile RG, Melcher A, Chester J, Pandha HS. Clinical trials with oncolytic reovirus: moving beyond phase I into combinations with standard therapeutics. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev (2010) 21:91–8 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahin E, Egger ME, McMasters KM, Zhou HS. Development of oncolytic reovirus for cancer therapy. J Cancer Ther (2013) 4:1100–15 10.4236/jct.2013.46127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee PW, Hayes EC, Joklik WK. Protein sigma 1 is the reovirus cell attachment protein. Virology (1981) 108:156–63 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90535-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boehme KW, Guglielmi KM, Dermody TS. Reovirus nonstructural protein σ1s is required for establishment of viremia and systemic dissemination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2009) 106:19986–91 10.1073/pnas.0907412106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi T, Chappell JD, Danthi P, Dermody TS. Gene-specific inhibition of reovirus replication by RNA interference. J Virol (2006) 80:9053–63 10.1128/JVI.00276-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul RW, Choi AH, Lee PW. The alpha-anomeric form of sialic acid is the minimal receptor determinant recognized by reovirus. Virology (1989) 172:382–5 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90146-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reiter DM, Frierson JM, Halvorson EE, Kobayashi T, Dermody TS, Stehle T. Crystal structure of reovirus attachment protein sigma1 in complex with sialylated oligosaccharides. PLoS Pathog (2011) 7:e100216. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiss K, Stencel JE, Liu Y, Blaum BS, Reiter DM, Feizi T, et al. The GM2 glycan serves as a functional coreceptor for serotype 1 reovirus. PLoS Pathog (2012) 8:e1003078. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barton ES, Forrest JC, Connolly JL, Chappell JD, Liu Y, Schnell FJ, et al. Junction adhesion molecule is a receptor for reovirus. Cell (2001) 104:441–51 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00231-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maginnis MS, Forrest JC, Kopecky-Bromberg SA, Dickeson SK, Santoro SA, Zutter MM, et al. Beta1 integrin mediates internalization of mammalian reovirus. J Virol (2006) 80:2760–70 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2760-2770.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mainou BA, Dermody TS. Transport to late endosomes is required for efficient reovirus infection. J Virol (2012) 86:8346–58 10.1128/JVI.00100-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sturzenbecker LJ, Nibert M, Furlong D, Fields BN. Intracellular digestion of reovirus particles requires a low pH and is an essential step in the viral infectious cycle. J Virol (1987) 61:2351–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maratos-Flier E, Goodman MJ, Murray AH, Kahn CR. Ammonium inhibits processing and cytotoxicity of reovirus, a nonenveloped virus. J Clin Invest (1986) 78:1003–7 10.1172/JCI112653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebert DH, Deussing J, Peters C, Dermody TS. Cathepsin L and cathepsin B mediate reovirus disassembly in murine fibroblast cells. J Biol Chem (2002) 277:24609–17 10.1074/jbc.M201107200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madren JA, Sarkar P, Danthi P. Cell entry-associated conformational changes in reovirus particles are controlled by host protease activity. J Virol (2012) 86:3466–73 10.1128/JVI.06659-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mainou BA, Zamora PF, Ashbrook AW, Dorset DC, Kim KS, Dermody TS. Reovirus cell entry requires functional microtubules. MBio (2013) 4:e405–13 10.1128/mBio.00405-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borsa J, Morash BD, Sargent MD, Copps TP, Lievaart PA, Szekely JG. Two modes of entry of reovirus particles into L cells. J Gen Virol (1979) 45:161–70 10.1099/0022-1317-45-1-161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashiro G, Loh PC, Yah JT. The preferential cytotoxicity of reovirus for certain transformed cell lines. Arch Virol (1977) 54:307–15 10.1007/BF01314776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duncan MR, Stanish SM, Cox DC. Differential sensitivity of normal and transformed human cells to reovirus infection. J Virol (1978) 28:444–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strong JE, Tang D, Lee PW. Evidence that the epidermal growth factor receptor on host cells confers reovirus infection efficiency. Virology (1993) 197:405–11 10.1006/viro.1993.1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell SL, Khosravi-Far R, Rossman KL, Clark GJ, Der CJ. Increasing complexity of Ras signaling. Oncogene (1998) 17:1395–413 10.1038/sj.onc.1202174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strong JE, Lee PW. The v-erbB oncogene confers enhanced cellular susceptibility to reovirus infection. J Virol (1996) 70:612–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bos JL. Ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res (1989) 49:4682–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shmulevitz M, Marcato P, Lee PW. Unshackling the links between reovirus oncolysis, Ras signaling, translational control and cancer. Oncogene (2005) 24:7720–8 10.1038/sj.onc.1209041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strong JE, Coffey MC, Tang D, Sabinin P, Lee PWK. The molecular basis of viral oncolysis: usurpation of the Ras signaling pathway by reovirus. EMBO J (1998) 17:3351–62 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norman KL, Hirasawa K, Yang AD, Shields MA, Lee PWK. Reovirus oncolysis: the Ras/RalGEF/p38 pathway dictates host cell permissiveness to reovirus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2004) 101:11099–104 10.1073/pnas.0404310101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imani F, Jacobs BL. Inhibitory activity for the interferon-induced protein kinase is associated with the reovirus serotype 1 sigma 3 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1988) 85:7887–91 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shmulevitz M, Pan LZ, Garant K, Pan D, Lee PWK. Oncogenic Ras promotes reovirus spread by suppressing IFN-β production through negative regulation of RIG-I signaling. Cancer Res (2010) 70:4912–21 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knowlton JJ, Dermody TS, Holm GH. Apoptosis induced by mammalian reovirus is beta interferon (IFN) independent and enhanced by IFN regulatory factor 3- and NF-κB-dependent expression of Noxa. J Virol (2011) 86:1650–60 10.1128/JVI.05924-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clemens MJ. PKR – a protein kinase regulated by double-stranded RNA. Int J Biochem Cell Biol (1997) 29:945–9 10.1016/S1357-2725(96)00169-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bischoff JR, Samuel CE. Mechanism of interferon activation of the human P1-eIF-2α protein kinase by individual reovirus s-class mRNAs: s1 mRNA is a potent activator relative to s4 mRNA. Virology (1989) 172:106–15 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90112-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mundschau LJ, Faller DV. Endogenous inhibitors of the dsRNA-dependent eIF-2α protein kinase PKR in normal and Ras-transformed cells. Biochimie (1994) 76:792–800 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90083-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alain T, Kim TS, Lun X, Liacini A, Schiff LA, Senger DL, et al. Proteolytic disassembly is a critical determinant for reovirus oncolysis. Mol Ther (2007) 15:1512–21 10.1038/sj.mt.6300207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mercato P, Shmulevitz M, Pan D, Stoltz D, Lee PWK. Ras transformation mediates reovirus oncolysis by enhancing virus uncoating, particle infectivity and apoptosis-dependent release. Mol Ther (2007) 15:1522–30 10.1038/sj.mt.6300179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collette J, Ulku AS, Der CJ, Jones A, Erickson AH. Enhanced cathepsin L expression is mediated by different Ras effector pathways in fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Int J Cancer (2004) 112:190–9 10.1002/ijc.20398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chambers AF, Colella R, Denhardt DT, Wilson SM. Increased expression of cathepsins L and B and decreased activity of their inhibitors in metastatic, Ras-transformed NIH 3T3 cells. Mol Carcinog (1992) 5:238–45 10.1002/mc.2940050311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clarke P, Meintzer SM, Wang Y, Moffitt LA, Richardson-Burns SM, Johnson GL, et al. JNK regulates the release of proapoptotic mitochondrial factors in reovirus-infected cells. J Virol (2004) 78:13132–8 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13132-13138.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ikeda Y, Nishimura G, Yanoma S, Kubota A, Furukawa M, Tsukuda M. Reovirus oncolysis in human head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Auris Nasus Larynx (2004) 31:407–12 10.1016/j.anl.2004.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan J, Kroemer G. Alternative cell death mechanisms in development and beyond. Genes Dev (2010) 24:2592–602 10.1101/gad.1984410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu W, Liu P, Li J. Necroptosis: an emerging form of programmed cell death. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol (2012) 82:249–58 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berger AK, Danthi P. Reovirus activates a caspase-independent cell death pathway. MBio (2013) 4:e178–113 10.1128/mBio.00178-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Errington F, White CL, Twigger KR, Rose A, Scott K, Steele L, et al. Inflammatory tumour cell killing by oncolytic reovirus for the treatment of melanoma. Gene Ther (2008) 15:1257–70 10.1038/gt.2008.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kominsky DJ, Bickel RJ, Tyler KL. Reovirus-induced apoptosis requires both death receptor- and mitochondrial-mediated caspase-dependent pathways of cell death. Cell Death Differ (2002) 9:926–33 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clarke P, Meintzer SM, Gibson S, Widmann C, Garrington TP, Johnson GL, et al. Reovirus-induced apoptosis is mediated by TRAIL. J Virol (2000) 74:8135–9 10.1128/JVI.74.17.8135-8139.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clarke P, Meintzer SM, Spalding AC, Johnson GL, Tyler KL. Caspase 8-dependent sensitization of cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis following reovirus-infection. Oncogene (2001) 20:6910–9 10.1038/sj.onc.1204842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kominsky DJ, Bickel RJ, Tyler KL. Reovirus-induced apoptosis requires mitochondrial release of Smac/DIABLO and involves reduction of cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein levels. J Virol (2002) 76:11414–24 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11414-11424.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Connolly JL, Dermody TS. Virion disassembly is required for apoptosis induced by reovirus. J Virol (2002) 76:1632–41 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1632-1641.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clarke P, DeBiasi RL, Goody R, Hoyt CC, Richardson-Burns S, Tyler KL. Mechanisms of reovirus-induced cell death and tissue injury: role of apoptosis and virus-induced perturbation of host-cell signaling and transcription factor activation. Viral Immunol (2005) 18:89–115 10.1089/vim.2005.18.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coffey CM, Sheh A, Kim IS, Chandran K, Nibert ML, Parker JSL. Reovirus outer capsid protein μ1 induces apoptosis and associates with lipid droplets, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria. J Virol (2006) 80:8422–38 10.1128/JVI.02601-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wisniewski ML, Werner BG, Hom LG, Anguish LJ, Coffey CM, Parker JSL. Reovirus infection or ectopic expression of outer capsid protein μ1 induces apoptosis independently of the cellular proapoptotic proteins Bax and Bak. J Virol (2011) 85:296–304 10.1128/JVI.01982-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Connolly JL, Rodgers SE, Clarke P, Ballard DW, Kerr LD, Tyler KL, et al. Reovirus-induced apoptosis requires activation of transcription factor NF-κB. J Virol (2000) 74:2981–9 10.1128/JVI.74.7.2981-2989.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pan D, Pan L-Z, Hill R, Marcato P, Shmulevitz M, Vassilev LT, et al. Stabilisation of p53 enhances reovirus-induced apoptosis and virus spread through p53-dependent NF-κB activation. Br J Cancer (2011) 105:1012–22 10.1038/bjc.2011.325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Danthi P, Pruijssers AJ, Berger AK, Holm GH, Zinkel SS, Dermody TS. Bid regulates the pathogenesis of neurotropic reovirus. PLoS Pathog (2010) 6:e1000980. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clarke P, Tyler KL. Down-regulation of cFLIP following reovirus infection sensitizes human ovarian cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis (2007) 12:211–23 10.1007/s10495-006-0528-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cho IR, Koh SS, Min HJ, Park EH, Srisuttee R, Jhun BH, et al. Reovirus infection induces apoptosis of TRAIL-resistant gastric cancer cells by down-regulation of akt activation. Int J Oncol (2010) 36:1023–30 10.3892/ijo_00000583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clarke P, Beckham JD, Leser JS, Hoyt CC, Tyler KL. Fas-mediated apoptotic signaling in the mouse brain following reovirus infection. J Virol (2009) 83:6161–70 10.1128/JVI.02488-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dionne KR, Zhuang Y, Leser JS, Tyler KL, Clarke P. Daxx upregulation within the cytoplasm of reovirus-infected cells is mediated by interferon and contributes to apoptosis. J Virol (2013) 87:3447–60 10.1128/JVI.02324-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nuovo GJ, Garofalo M, Valeri N, Roulstone V, Volinia S, Cohn DE, et al. Reovirus-associated reduction of microRNA-let-7d is related to the increased apoptotic death of cancer cells in clinical samples. Mod Pathol (2012) 25:1333–44 10.1038/modpathol.2012.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thirukkumaran CM, Shi ZQ, Luider J, Kopciuk K, Gao H, Bahlis N, et al. Reovirus as a viable therapeutic option for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res (2012) 18:4962–72 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thirukkumaran CM, Shi ZQ, Luider J, Kopciuk K, Gao H, Bahlis N, et al. Reovirus modulates autophagy during oncolysis of multiple myeloma. Autophagy (2013) 9:413–4 10.4161/auto.22867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chiu HC, Richart S, Lin FY, Hsu WL, Liu HJ. The interplay of reovirus with autophagy. Biomed Res Int (2014) 2014:8. 10.1155/2014/483657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meng S, Jiang K, Zhang X, Zhang M, Zhou Z, Hu M, et al. Avian reovirus triggers autophagy in primary chicken fibroblast cells and vero cells to promote virus production. Arch Virol (2012) 157:661–8 10.1007/s00705-012-1226-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qin L, Wang Z, Tao L, Wang Y. ER stress negatively regulates AKT/TSC/mTOR pathway to enhance autophagy. Autophagy (2010) 6:239–47 10.4161/auto.6.2.11062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kelly KR, Espitia CM, Mahalingam D, Oyajobi BO, Coffey M, Giles FJ, et al. Reovirus therapy stimulates endoplasmic reticular stress, Noxa induction, and augments bortezomib-mediated apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Oncogene (2012) 31:3023–38 10.1038/onc.2011.478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Song L, Ohnuma T, Gelman IH, Holland JF. Reovirus infection of cancer cells is not due to activated Ras pathway. Cancer Gene Ther (2009) 16:382. 10.1038/cgt.2008.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Twigger K, Roulstone V, Kyula J, Karapanagiotou EM, Syrigos KN, Morgan R, et al. Reovirus exerts potent oncolytic effects in head and neck cancer cell lines that are independent of signalling in the EGFR pathway. BMC Cancer (2012) 12:368. 10.1186/1471-2407-12-368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heinemann L, Simpson GR, Annels NE, Vile R, Melcher A, Prestwich R, et al. The effect of cell cycle synchronization on tumor sensitivity to reovirus oncolysis. Mol Ther (2010) 18:2085–93 10.1038/mt.2010.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]