Abstract

Introduction:

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and Diabetes Mellitus (DM) are growing health challenges worldwide. However, the relation of OSA with type 2 diabetes is not well understood in developing countries. This study described the prevalence and predictors of OSA in type 2 DM patients using a screening questionnaire.

Materials and Methods:

Patients aged 40years and above with type 2 diabetes mellitus were recruited into the study consecutively from the outpatient clinics of a university hospital. They were all administered the Berlin questionnaire and the Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) to assess the risk of OSA and the tendency to doze off, respectively. Anthropometric details like height, weight and body mass index (BMI) were measured and short-term glycaemic control was determined using fasting blood glucose.

Results:

A total of 117 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were recruited into the study. The mean (SD) age, height and BMI was 63 years (11), 160 cm (9) and 27.5 kg/ m2 (5.7), respectively. Twenty-seven percent of the respondents had a high risk for OSA and 22% had excessive daytime sleepiness denoted by ESS score above 10. In addition, the regression model showed that for every 1 cm increase in neck circumference, there is a 56% independent increase in the likelihood of high risk of OSA after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, waist, hip circumferences and blood glucose.

Conclusion:

Our study shows a substantial proportion of patients with type 2 diabetes may have OSA, the key predictor being neck circumference after controlling for obesity.

Keywords: Diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, sleep

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and diabetes mellitus (DM) are growing health challenges in both high and low-income countries.1,2 OSA is often the result of inspiratory flow limitation and obstruction resulting in snoring and recurrent apnoeic episodes during sleep. It frequently manifest as excessive daytime somnolence, poor performance at work and increased predisposition to domestic and occupational accidents.3

Several epidemiologic studies have shown that OSA is independently associated with cardiovascular diseases and metabolic conditions like insulin resistance and type 2 DM.4,5,6,7

OSA has also been shown to impact on glycaemic control among DM patients independent of the effect of obesity.4 The postulated mechanisms of this effect include sleep fragmentation, frequent arousals, intermittent hypoxaemia and consequently, hyper-activation of sympathetic mechanisms leading to poor glucose control.8

However, the impact of OSA among patients with type 2 diabetes is unknown and infrequently studied in developing countries where the burden of DM is substantial and increasing.9 To the best of our knowledge, there is no study on the prevalence and predictors of OSA in patients with diabetes in Nigeria or any population of patients with diabetes in West Africa.

We hypothesise that OSA is prevalent in type 2 diabetes. We aimed to describe the prevalence of OSA in type 2 DM patients using a screening questionnaire and to ascertain the predictors of a high risk of OSA after adjusting for obesity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey of patients attending the outpatient endocrinology clinics of Wesley Guild Hospital (WGH), Ilesha and Ife Specialist Hospital (ISH), Ile-Ife. Both hospitals are part of Obafemi Awolowo University Hospital, Nigeria. Patients who were confirmed diabetic based on World Health Organisation (WHO) criteria of fasting glucose of at least 7.0 mmol/l and commenced on oral hypoglycaemic agents were recruited consecutively into the survey.10

The Berlin questionnaire was administered to all the eligible participants. The Berlin questionnaire is a validated instrument widely used to screen for obstructive sleep apnea.11 It includes questions on snoring, witnessed apnea, wake time sleepiness and self-reported hypertension. It is classified into three categories. Category 1 includes five questions on snoring and witnessed apnoea. Category 2 includes three questions on wake time sleepiness and drowsiness behind the steering wheel while category 3 comprises self-reported diagnosis of high blood pressure and body mass index (BMI). Category 1 and 2 were considered positive if two or more questions were reported positive at least three times/week, while category 3 was positive if participant have been diagnosed as hypertensive or had BMI greater than 30 kg/ m2. Participants that satisfied the criteria in two or more categories were regarded as high risk while the others were considered low risk for OSA.

Snoring was classified as simple for those who snore two times/week or less and habitual for those who snore greater than three times/week and as loudly as talking. Non-snorers were those who answered negative to the question: “Do you snore?”

Epworth sleepiness scale

Sleepiness was measured using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). The ESS is a validated questionnaire that is used to assess the risk of daytime somnolence and it has been shown to be valid and sensitive.12 It estimates a participant's likelihood to doze off or fall asleep in eight different scenarios associated with daily activities. Each item was measured by a four-point scale, with a possible score ranging from zero (0) to 24. A score of greater than 10 was regarded as indicative of excessive daytime sleepiness.

Diabetic control on the short term was evaluated using the most recent fasting blood glucose. Patients who had their most recent fasting glucose below 6.1 mmol/l were considered controlled while those with fasting glucose values equal or above 6.1 mmol/l were considered uncontrolled.

Data analysis

The analysis was done using Stata 11.2 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).13 Categorical data were presented using proportions and frequencies while continuous data was presented in mean and standard deviation. Where appropriate, the chi-square test or fisher's exact test was used to test for differences between proportions while the student t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare continuous variables. Logistic models were developed to assess the key predictors of OSA while adjusting for confounding variables like age, sex, BMI and waist circumference. The results are presented as adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). A two-sided P value <0.05 indicate statistical significance. Ethical clearance was obtained for the survey from the local university hospital ethics board.

RESULTS

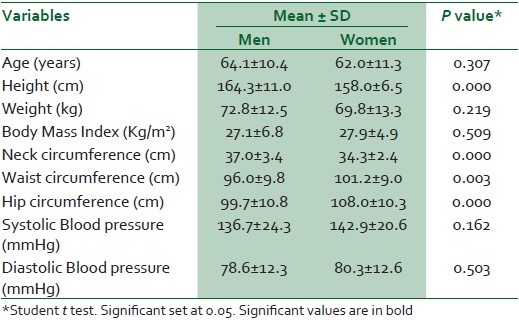

A total of 117 patients with type 2 DM aged 40 years and above were recruited into the survey. Forty-four percent of the respondents were men. The mean age (SD) was 64.1 (10.4) and 62.0 (11.3) years for men and women, while the mean BMI was 27.1 (6.8) and 27.9 (4.9) kg/ m2, respectively [Table 1].

Table 1.

General characteristics of the participants

Men had larger necks (P < 0.001) while the women were more likely to have large waist and hip circumferences (P < 0.001).

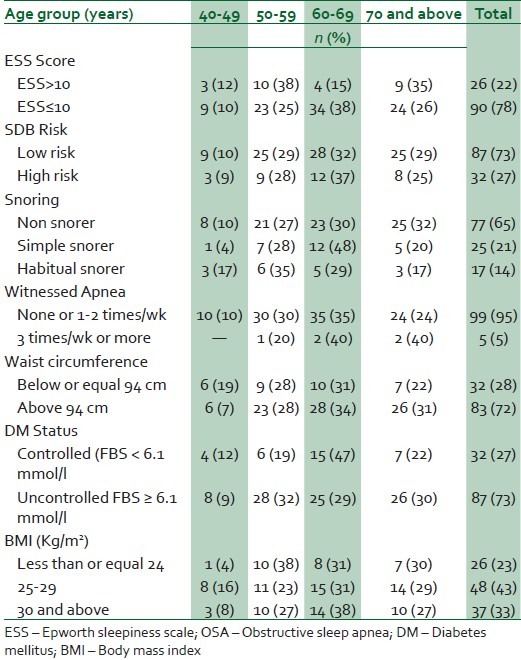

Table 2 shows that 27% of the respondents had a high risk for OSA and 22% had excessive daytime sleepiness denoted by ESS score above 10. About 76% of the respondents had BMI of at least 25 kg/ m2 and 73% of the participants had uncontrolled diabetes based on their most recent fasting glucose.

Table 2.

Distribution of risk factors by age group

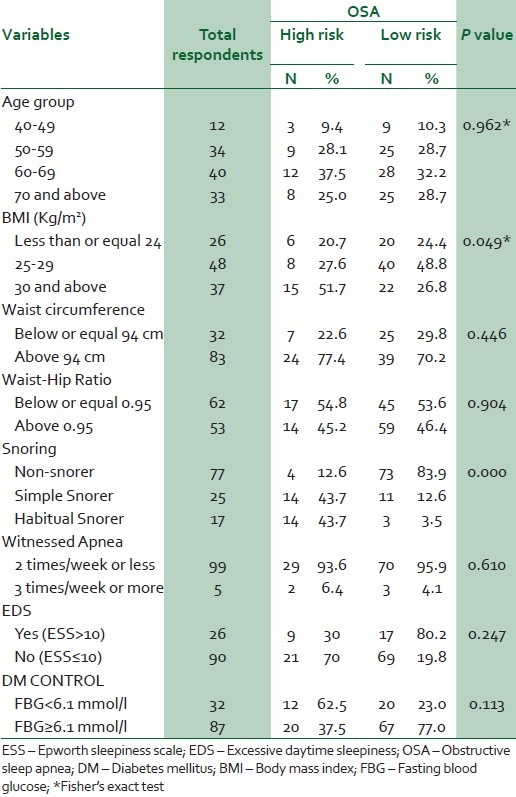

Table 3 shows the results of the bivariate comparison of the risk of OSA. It shows that those with a BMI of at least 30 kg/ m2 and habitual snorers were more likely to have a high risk of OSA (P < 0.05) and (P < 0.01), respectively. Age, excessive daytime sleepiness, measures of regional obesity like waist and hip circumferences and fasting blood glucose levels were not significant determinants of risk of OSA.

Table 3.

Bivarate analysis of OSA risk and potential risk factors

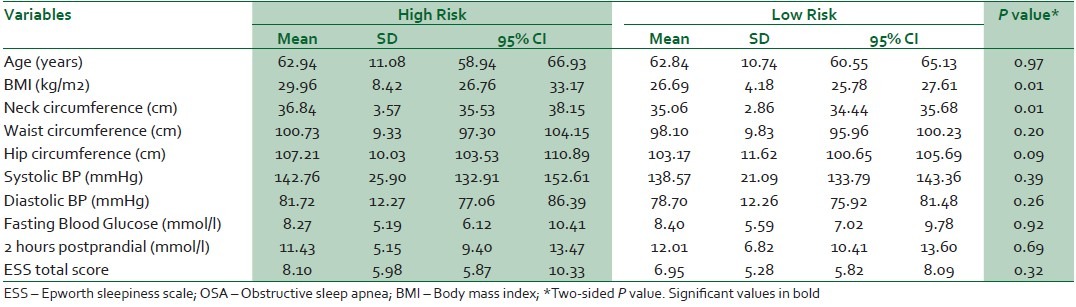

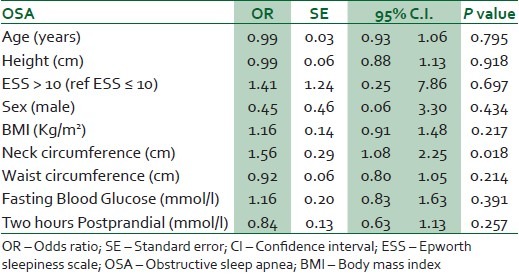

Respondents with a high risk of OSA had mean neck circumferences and BMIs significantly larger than those with a low risk [Table 4]. In the logistic regression analysis with risk of OSA as dependent variable, the results showed that for every cm increase in neck circumference, there is a 56% independent increase in the likelihood of a high risk of OSA adjusting for age, sex, general and regional obesity (BMI, waist, hip circumferences) and blood glucose (fasting glucose and 2 hours post prandial) [Table 5].

Table 4.

Study parameters according to risk of obstructive sleep apnea

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis of predictors of OSA in type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that 27% of patients with type 2 DM has a high risk for OSA. In addition, neck circumference was a key predictor of OSA among patients with type 2 diabetes after controlling for obesity, age, sex, height and blood glucose.

The ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis of OSA is overnight Polysomnography. However, in its absence, questionnaire based surveys are good screening tools for efficient selection of those with a high risk for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Netzer et al., in a survey of 1,008 adults attending a primary care clinic using the Berlin questionnaire, showed that being in the high-risk group predicted an Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) of >5 with a sensitivity of 0.86 and a positive predictive value of 0.89.11

Questionnaire estimates are generally under estimates as they are often lower in sensitivity compared to analysis based on full overnight sleep studies. So, our reports suggest that the actual prevalence of sleep disorders and apnea may be much higher than presently reported.

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is estimated to occur in 3-7% of men and 2-5% of women in the general population, however, reports from several studies suggest that the prevalence among patients with type 2 diabetes may be higher.6,14

West and colleagues in a review of the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in men with type 2 diabetes using symptoms of daytime sleepiness, snoring and reported apnoeic episodes derived from the Berlin questionnaire found that 57% of the respondents were scored as high risk for sleep apnea while 39% were low risk.15 Studies based on full polysomnography suggest that the prevalence of OSA in type 2 DM is high. Resnick et al., in a survey of 216 diabetic men, who participated in the Sleep Heart Health Study, found that 58% of the respondents had mild OSA (AHI ≥ 5) while 24% had moderate-severe OSA (AHI > 15).16 Foster et al., also observed in an analysis of the data of 122 obese men with type 2 diabetes enrolled in the Sleep Action for Health in Diabetes (AHEAD) study trial, 86.6% of the participants had some degree of OSA.17 Similarly, Aronsohn et al., in another report based on physician diagnosed DM in a primary care setting, noted that 77% of the patients had OSA based on AHI of at least 5.18

The presence of co morbid conditions like OSA potentially impacts on the control of DM and the effectiveness of the strategies for reducing the medium and long-term complications.18 Obstructive sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes share common risk factors especially visceral adiposity, advancing age and obesity.19,20 Obesity impacts on the development of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and the risk of developing diabetes or its effective control. However, recent reports suggest that independent of obesity, sleep disorders also exerts a direct effect on the development and control of diabetes.18

We also found that neck circumference predicts a high risk of OSA after adjusting for height, obesity and blood glucose level. We noted that after adjusting for age, sex, height, BMI and waist circumference, for every centimetre increase in neck circumference, the risk of OSA increases by over 50%. Our finding supports previous studies that showed that neck circumference is an important predictor of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Davies et al., in a study of 150 patients referred to a sleep clinic reported that neck circumference corrected for height is a more useful predictor of obstructive sleep apnea than general obesity.21 Stradling and colleagues in an analysis of 1,001 randomly selected middle aged men from the register of a general practice clinic, observed that self-reported snoring correlated best with neck size, smoking and nasal stuffiness. In addition, they noted that nocturnal hypoxaemia of at least 4% dip in oxygen saturation was best predicted by neck size and use of alcohol but less so with age or obesity.20

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, the lack of confirmatory tests of overnight polysomnography and pulse oximetry means the possibility of misclassification of some cases cannot be excluded. However, the Berlin questionnaire has been shown to be sensitive in detecting positive cases. More so, the direction of effect for this questionnaire-based study is more likely to be an underestimate rather than an overestimate. Secondly, glycated haemoglobin values are not reported. This would have been a more reliable measure of the level of glucose control.

However, among the strengths of the present study are the facts that, it pioneers and highlights the need for further sleep studies among patients with diabetes in low-income countries, especially research focussing on the contributory impact of sleep disorders on the control of diabetes. Physicians need to consider the possibility of OSA even in the absence of symptoms especially in type 2 diabetics with large neck circumferences. It is important for care providers to understand the role of sleep apnea in the morbidity due to diabetes in order to adopt a holistic approach in their care.

In conclusion, the present study shows that OSA is a common disorder among persons with diabetes in Nigeria and neck circumference is the key determinant after adjusting for age, sex, height and obesity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We wish to thank Francis Awoniyi for his secretariat assistance in developing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Punjabi NM, Polotsky VY. Disorders of glucose metabolism in sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1998–2007. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00695.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: A population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1217–39. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, Redline S, Newman AB, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Sleep Heart Health Study Research Group. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: The sleep heart health study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:893–900. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.8.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ip MS, Lam B, Ng MM, Lam WK, Tsang KW, Lam KS. Obstructive sleep apnea is independently associated with insulin resistance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:670–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.5.2103001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, Gottlieb DJ, Givelber R, Resnick HE. Sleep Heart Health Study Investigators. Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: The sleep heart health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:521–30. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reichmuth KJ, Austin D, Skatrud JB, Young T. Association of sleep apnea and type II diabetes: A population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1590–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200504-637OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, Shahar E, Samet JM, Redline S, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renko AK, Hiltunen L, Laakso M, Rajala U, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S. The relationship of glucose tolerance to sleep disorders and daytime sleepiness. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;67:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall V, Thomsen RW, Henriksen O, Lohse N. Diabetes in sub Saharan Africa 1999-2011: Epidemiology and public health implications. A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:564. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:593–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:485–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.StataCorp L. Stata version 11.0. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laaban JP, Daenen S, Leger D, Pascal S, Bayon V, Slama G, et al. Prevalence and predictive factors of sleep apnoea syndrome in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab. 2009;35:372–7. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West SD, Nicoll DJ, Stradling JR. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea in men with type 2 diabetes. Thorax. 2006;61:945–50. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.057745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resnick HE, Redline S, Shahar E, Gilpin A, Newman A, Walter R, et al. Sleep Heart Health Study. Diabetes and sleep disturbances: Findings from the sleep heart health study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:702–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster GD, Sanders MH, Millman R, Zammit G, Borradaile KE, Newman AB, et al. Sleep AHEAD Research Group. Obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1017–9. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aronsohn RS, Whitmore H, Van Cauter E, Tasali E. Impact of untreated obstructive sleep apnea on glucose control in type 2 diabetes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:507–13. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1423OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seneviratne U, Puvanendran K. Excessive daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea: Prevalence, severity, and predictors. Sleep Med. 2004;5:339–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stradling JR, Crosby JH. Predictors and prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea and snoring in 1001 middle aged men. Thorax. 1991;46:85–90. doi: 10.1136/thx.46.2.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies RJ, Ali NJ, Stradling JR. Neck circumference and other clinical features in the diagnosis of the obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Thorax. 1992;47:101–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]