Abstract

Rivaroxaban is an oral anticoagulant agent that directly inhibits Factor Xa and interrupts both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathway of the coagulation cascade and is currently indicated for use in patients for atrial fibrillation and prophylaxis of deep venous thrombosis. The present case reports of spontaneous rectus sheath hematoma during rivaroxaban therapy for atrial fibrillation in a 75-year-old woman.

KEY WORDS: Oral anticoagulants, rivaroxaban, spontaneous rectus sheath hematoma

Introduction

Recently, new oral anticoagulants have been approved as alternatives to warfarin for patients with atrial fibrillation. Rivaroxaban is one of the novel anticoagulants, which is an oxazolidinone derivative and inhibits both free Factor Xa and Factor Xa bound with the prothrombinase complex. It is a highly selective direct Factor Xa inhibitor with oral bioavailability and rapid onset of action. There are some advantages of the new agents compared with warfarin including rapid anticoagulation after an oral dose and lack of dietary or drug-drug interaction. However, there are no specific antidotes for the anticoagulant effect of rivaroxaban in the event of a major bleeding, unlike warfarin. We present a case of spontaneous rectus sheath hematoma (RSH) during rivaroxaban therapy for atrial fibrillation in an elderly female patient.

Case Report

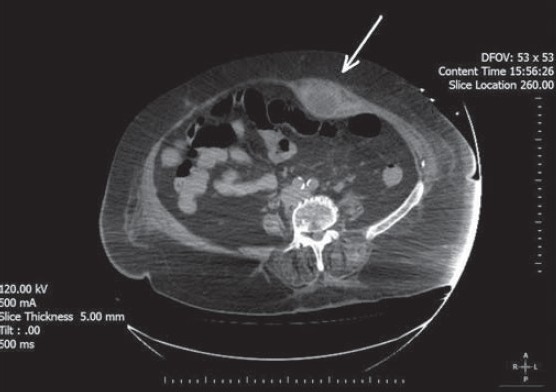

A 75-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with the complaints of fatigue and abdominal pain after coughing. The patient had been started on new oral anticoagulant agent rivaroxaban therapy for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation for 3 days. The dose of 20 mg/day rivaroxaban was started because the creatinin clearance of the patient was above 50 mL/min. She had a blood pressure of 70/40 mmHg and an irregular heart rate of 115 beats/min on admission. Physical examination revealed tenderness and mild abdominal swelling with no skin discoloration. The patient had no history of any trauma or surgery; she reported that the symptoms started after vigorous coughing. The patient also denied taking any other drugs that could cause bleeding. Blood analyses revealed leukocytosis (26.5 k/uL) accompanied by severe anemia (5.4 g/dl). Platelet counts were within normal ranges and her international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.48. Her abdominal X-ray was normal and the stool occult blood test was negative. Anticoagulant treatment was stopped and was resuscitated with fluid and packed red blood cells. After the first treatment, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). Repeated abdominal examination in the ICU revealed increased tenderness and a palpable mass on the left side of the umbilicus. Noncontrast abdominal computerized tomography scan showed a left-sided RSH, 102 × 45 mm in size [Figure 1]. A specific antidote for rivaroxaban is not available then the patient was treated with fluid resuscitation and packed red blood cells. The patient was referred to surgery because of the hemodynamic instability.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen shows a left-sided rectus sheath hematoma (arrow)

Discussion

Rivaroxaban is an oral anticoagulant agent that directly inhibits Factor Xa and interrupts both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathway of the coagulation cascade. Rivaroxaban is currently indicated for use in patients for atrial fibrillation and prophylaxis of deep venous thrombosis. It does not require INR monitoring like warfarin. With the increasing use of the new anticoagulant agents like rivaroxaban in atrial fibrillation, bleeding complications due to these agents have been frequently seen. There are no specific antidotes for the anticoagulant effect of rivaroxaban and other new oral anticogulants unlike warfarin, thus the management of the bleeding complications include support and observation. Currently, no available specific antidote exists for the management of rivaroxaban-associated bleeding events, but supporting therapy is useful which are likely to be effective for the majority of patients because of the short half-lives of these agents.

Recent studies showed that rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin for the primary endpoint of stroke and systemic embolism.[1] There was no reduction in rates of mortality or ischemic stroke, but a significant reduction in hemorrhagic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage. The primary safety endpoint was the composite of major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, which was not significantly different between rivaroxaban and warfarin but, with rivaroxaban, there was a significant reduction in fatal bleeding, as well as an increase in gastrointestinal bleeds and bleeds requiring transfusion.

Rectus sheath hematoma is a rare but important complication of anticoagulant therapy. The main causes of the RSH include anticoagulant therapy, hematological disorders, trauma, excessive physical exercise, coughing, sneezing, and pregnancy.[2] Especially in elderly patients the risk of RSH may be increased due to the impaired functional status and weakened rectus muscle. Early recognition, rapid assessment and treatment are important to reduce the complications such as hemodynamic instability, abdominal compartment syndrome, multiorgan dysfunction and even death. The treatment of such a hematoma includes transfusion with packed red blood cells and supporting therapy based on regularly monitoring of hemoglobin levels. The offending agent must be discontinued as quickly as possible. Rivaroxaban has a mean terminal half-life of 7-11 h so in bleeding events supporting therapies are likely to be effective for the majority of patients. There is no obvious antidote to reverse the effects of the rivaroxaban. Several studies have shown that prothrombin complex concentrate may be useful in reversing the effects of rivaroxaban. Other possible measures include the use of recombinant Factor VIIa to reduce bleeding or the use of activated charcoal to reduce absorption in cases of overdose.[3]

Several factors are reported which increase the risk of patients developing hemorrhage while receiving rivaroxaban, these include advanced age, hypertension, history of hepatic/renal disease, previous stroke, coagulopathy, concomitant use of antiplatelet agents and alcohol consumption. Jaeger et al. have reported a 61-year-old female patient who developed a spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma after being treated by rivaroxaban.[4] Boland et al. also reported acute onset severe gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage in a postoperative patient taking rivaroxaban after total hip arthroplasty.[5]

In our patient, there was no other medication except rivaroxaban that could cause the hematoma. Based on Naranjo's scale, a score of 7 showed that the rivaroxaban was the probable cause of the RSH. Several case reports of muscle hematoma due to the antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents have been reported previously, but this is the first reported case of spontaneous RSH due to the rivaroxaban.[6]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict Interest: No

References

- 1.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: Review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:105–10. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen PW, Sijpkens MK, Meijers JC, Buller HR, Levi M. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011;124:1573–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaeger M, Jeanneret B, Schaeren S. Spontaneous spinal epidural haematoma during Factor Xa inhibitor treatment (Rivaroxaban) Eur Spine J. 2012;21(Suppl 4):S433–5. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-2003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boland M, Murphy M, Murphy M, McDermott E. Acute-onset severe gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage in a postoperative patient taking rivaroxaban after total hip arthroplasty: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:129. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cakar MA, Kocayigit I, Aydin E, Demirci H, Gunduz H. Clopidogrel-induced spontaneous pectoral hematoma. Indian J Pharmacol. 2012;44:526–7. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.99342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]