This study was designed to determine the appropriate clinical dose of netupitant (NETU), a new NK1 receptor antagonist (RA), to combine with the 5-HT3 RA, palonosetron (PALO) in a fixed-dose antiemetic combination (NEPA). All NEPA doses provided superior prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting compared with PALO, with NEPA300 (300mg NETU + 0.50 mg PALO) being the best dose studied.

Keywords: neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, NEPA, netupitant, palonosetron, CINV, highly emetogenic

Abstract

Background

NEPA is a novel oral fixed-dose combination of netupitant (NETU), a new highly selective neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptor antagonist (RA) and palonosetron (PALO), a pharmacologically and clinically distinct 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 (5-HT3) RA. This study was designed to determine the appropriate clinical dose of NETU to combine with PALO for evaluation in the phase 3 NEPA program.

Patients and methods

This randomized, double-blind, parallel group study in 694 chemotherapy naïve patients undergoing cisplatin-based chemotherapy for solid tumors compared three different oral doses of NETU (100, 200, and 300 mg) + PALO 0.50 mg with oral PALO 0.50 mg, all given on day 1. A standard 3-day aprepitant (APR) + IV ondansetron (OND) 32 mg regimen was included as an exploratory arm. All patients received oral dexamethasone on days 1–4. The primary efficacy endpoint was complete response (CR: no emesis, no rescue medication) during the overall (0–120 h) phase.

Results

All NEPA doses showed superior overall CR rates compared with PALO (87.4%, 87.6%, and 89.6% for NEPA100, NEPA200, and NEPA300, respectively versus 76.5% PALO; P < 0.050) with the highest NEPA300 dose studied showing an incremental benefit over lower NEPA doses for all efficacy endpoints. NEPA300 was significantly more effective than PALO and numerically better than APR + OND for all secondary efficacy endpoints of no emesis, no significant nausea, and complete protection (CR plus no significant nausea) rates during the acute (0–24 h), delayed (25–120 h), and overall phases. Adverse events were comparable across groups with no dose response. The percent of patients developing electrocardiogram changes was also comparable.

Conclusions

Each NEPA dose provided superior prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) compared with PALO following highly emetogenic chemotherapy; however, NEPA300 was the best dose studied, with an advantage over lower doses for all efficacy endpoints. The combination of NETU and PALO was well tolerated with a similar safety profile to PALO and APR + OND.

introduction

Advances in understanding the physiology of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) have allowed for improvements in control of CINV with targeted prophylactic medications aimed at inhibiting various molecular pathways involved in emesis. Antiemetic regimens have consequently evolved from the use of dopamine antagonists alone to combination regimens such as a corticosteroid plus a serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) type 3 receptor antagonist (5-HT3 RA) with or without a neurokinin-1 (NK1) RA. Such combination regimens have become the standard of care for the prevention of CINV and are currently reflected in international antiemetic guidelines [1]. However, despite the availability of more effective prophylactic regimens, many patients are undertreated and still experience CINV [1], particularly nausea, during the delayed phase after chemotherapy.

NEPA is an oral fixed-dose combination of netupitant (NETU), a new highly selective NK1 RA and palonosetron (PALO), a pharmacologically distinct [2] and clinically superior [3–5] 5-HT3 RA. It targets two critical pathways associated with acute and delayed CINV, the serotonin and substance P-mediated pathways. The binding of PALO to the 5-HT3 receptor is distinctly different from older 5-HT3 RAs; recent in vitro data have shown that PALO not only independently inhibits the substance P response, but also enhances this inhibition when combined with NETU [6]. This in vitro synergy combined with PALO's clinical superiority to the older 5-HT3 RAs drove the decision to formulate a fixed-dose combination with NETU, recognizing that this also conveniently offers guideline-based prophylaxis in a single oral dose. A positron emission tomography (PET) study demonstrated that the 300 mg dose of NETU was the minimal dose among those tested (100, 300, and 450 mg), leading to a receptor occupancy in the striatum of >90% [7]. This led to the selection of the doses in the current trial.

This phase 2, pivotal study was designed to evaluate three different oral doses of NETU (100, 200, and 300 mg) co-administered with PALO 0.50 mg to determine the most appropriate clinical dose for the fixed-dose NEPA combination for evaluation in the phase 3 clinical program. The 0.50 mg oral PALO dose was selected based on an efficacy trial which evaluated the non-inferiority of three oral PALO doses, 0.25, 0.50, and 0.75 mg, compared with IV PALO 0.25 mg [8, 9] and served as the basis for FDA approval of the 0.50 mg oral dose. As cisplatin is viewed as the most emetogenic chemotherapeutic agent, it was thought to be the most useful setting in initially assessing the antiemetic efficacy of the NETU plus PALO combination (referred to as NEPA throughout). An exploratory 3-day standard aprepitant (APR)/ondansetron arm was also included to assess the relative activity of an approved NK1/5-HT3 RA combination within the context of this trial.

patients and methods

study design

This was a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel group study conducted at 29 sites in Russia and 15 sites in Ukraine in 2008. The protocol was approved by ethical review committees for each center, all patients provided written informed consent, and all investigators and site personnel were required to follow Good Clinical Practice, International Conference on Harmonization, and Declaration of Helsinki principles, local laws, and regulations.

patients

Eligible patients were ≥18 years diagnosed with histologically or cytologically confirmed malignant solid tumors, naïve to chemotherapy, and scheduled to receive their first course of cisplatin-based chemotherapy at a dose of ≥50 mg/m2 either alone or in combination with other chemotherapy agents. Patients were required to have a Karnofsky Performance Scale score of ≥70%, be able to follow study procedures and complete the patient diary. Patients were not eligible if they were scheduled to receive: (i) moderately (MEC) or highly (HEC) emetogenic chemotherapy from day 2 to 5 following chemotherapy, (ii) moderately or highly emetogenic radiotherapy either within 1 week before day 1 or from day 2 to 5, or (iii) a bone marrow or stem cell transplant. Patients were not allowed to receive any drug with potential antiemetic efficacy within 24 h or systemic corticosteroids within 72 h before day 1. They were excluded if they experienced any vomiting, retching, or more than mild nausea within 24 h before day 1. Patients were not to have had any serious cardiovascular disease history or predisposition to cardiac conduction abnormalities, with the exception of incomplete right bundle branch block. Because NETU is a moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4, chronic use of any CYP3A4 substrates/inhibitors/inducers or intake within 1 week (substrates/inhibitors) or 4 weeks (inducers) before day 1 was prohibited.

treatment

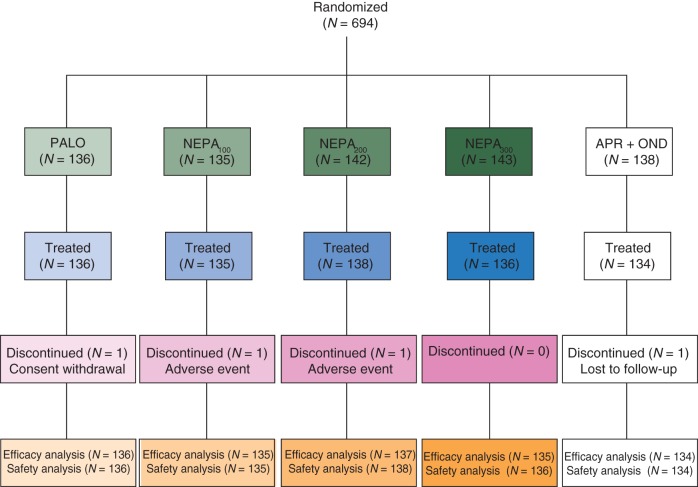

Patients were randomly assigned, stratified by gender, to one of the five treatment groups shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Treatment schema. PALO, palonosetron; NEPA, combination of PALO + netupitant (NETU); APR, aprepitant; DEX, dexamethasone; OND, ondansetron. NETU, PALO, and APR were administered 60 min before cisplatin on day 1, DEX was administered 30 min before cisplatin on day 1, OND was administered as 50 ml infusion of at least 15 min duration before cisplatin on day 1.

Owing to the potential for increased exposure to dexamethasone, the dexamethasone dose in the NK1 arms was reduced to achieve exposure similar to that in the PALO group. Cisplatin (≥50 mg/m2) was administered as a 1- to 4-h infusion; if administered in combination with other chemotherapy, it was administered first. Blinding was maintained with the use of matching identical placebos.

Rescue medication was permitted for the treatment of refractory and persistent nausea and vomiting; however, the use of these medications was considered treatment failure. The timing and choice of rescue (excluding 5-HT3 or NK1 RAs) was at the discretion of the investigator.

assessments

To assess efficacy, each patient completed a diary from the start of cisplatin infusion on day 1 through the morning of day 6 (0–120 h). The diary captured information pertaining to the timing and duration of each emetic episode, severity of nausea, concomitant medications taken including rescue, and the patient's overall satisfaction. An emetic episode was defined as a single vomiting occurrence, a single retching, or any retching combined with vomiting. Severity of nausea was evaluated by the patient on a daily basis (for the preceding 24 h) using a 100-mm horizontal visual analog scale (VAS). The left end (0 mm) was labeled as ‘no nausea’, and the right end (100 mm) was labeled as ‘nausea as bad as it could be’.

The primary efficacy endpoint was complete response (CR: no emesis, no rescue medication) during the overall (0–120 h) phase post-chemotherapy. Secondary efficacy endpoints included CR rates during the acute (0–24 h) and delayed (25–120 h) phases, and also no emesis, no significant nausea (VAS score of <25 mm), and complete protection (CR + no significant nausea) rates during the acute/delayed/overall phases. Safety was assessed primarily by adverse events, but also by clinical laboratory evaluations, vital signs, physical examination findings, and electrocardiograms (ECGs).

statistical analysis

The primary aim of this study was to determine whether at least one of three doses of NETU combined with PALO was more effective than PALO alone based on the CR rate during the overall 0–120 h phase.

For the sample size calculation, the assumption was an overall CR rate of 70% in the NEPA group(s) and 50% in the PALO group (based, in part, on IV PALO data in patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy). For a one-sided test of difference, using α = 0.0166 (obtained as type I error divided by the number of comparisons = 0.050/3), a sample size of 129 evaluable patients per group was needed to ensure 85% power for each comparison. The number was rounded up to 136 per group for a total of 680 patients.

An intent-to-treat approach was used for the efficacy analysis with the full analysis set defined as all patients who were randomized to treatment and received the protocol-required cisplatin and at least one dose of study treatment. The safety analysis population consisted of all patients who received at least one study treatment and had at least one safety assessment after treatment administration.

The primary efficacy analysis was carried out using a logistic regression adjusted for gender, where each dose of NEPA was compared with PALO alone. The Holm–Bonferroni method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons. The same logistic regression analysis adjusting for gender was utilized for the secondary efficacy endpoints with no adjustments for multiplicity. A post hoc logistic regression analysis comparing the exploratory APR arm with PALO was also carried out for the efficacy endpoints. The study was not powered for nor analyzed to show a difference between the NEPA groups and the APR-based regimen.

The number of patients who experienced treatment-emergent adverse events or ECG abnormalities was listed and summarized by the treatment group.

results

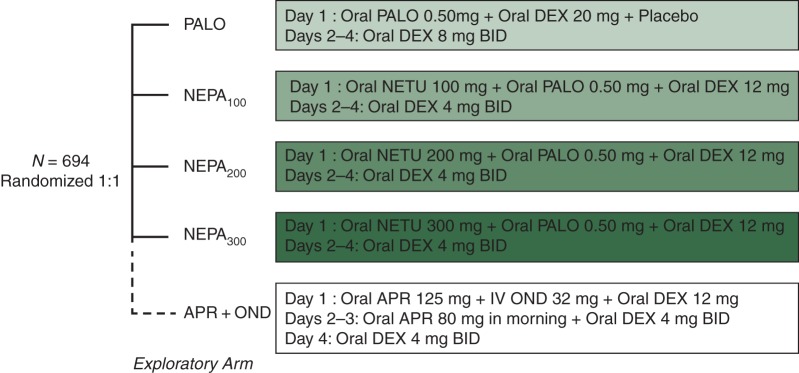

A total of 694 patients were randomized; 15 patients did not receive study treatment and were not included in the safety population and 677 (98%) patients were included in the full analysis set (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Consort diagram of the disposition of patients.

Baseline characteristics of the full analysis set were comparable across treatment groups and are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient baseline and disease characteristics

| Characteristic | PALO (N = 136) | NEPA100 (N = 135) | NEPA200 (N = 137) | NEPA300 (N = 135) | APR + OND (N = 134) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | |||||

| Male | 57.4 | 57.0 | 57.7 | 57.0 | 56.0 |

| Female | 42.6 | 43.0 | 42.3 | 43.0 | 44.0 |

| Median age (years) | 55.0 | 55.0 | 55.0 | 53.0 | 55.5 |

| Alcohol consumption (%) | |||||

| No | 58.1 | 58.5 | 59.1 | 54.1 | 56.0 |

| Rarely | 37.1 | 34.8 | 34.3 | 37.8 | 39.6 |

| Occasionally | 4.4 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 8.1 | 4.5 |

| Cancer type (%) | |||||

| Lung/respiratory | 30.1 | 28.9 | 25.5 | 25.9 | 26.1 |

| Head and neck | 17.6 | 20.0 | 22.6 | 24.4 | 19.4 |

| Ovarian | 16.9 | 13.3 | 14.6 | 17.8 | 18.7 |

| Other urogenital | 13.2 | 14.1 | 18.2 | 11.1 | 13.4 |

| Gastric | 5.9 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 5.9 | 6.0 |

| Other GI | 7.4 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 4.4 | 7.5 |

| Breast | 2.9 | 8.1 | 4.4 | 5.9 | 5.2 |

| Other | 5.9 | 6.0 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 3.7 |

| Karnofsky Index (%) | |||||

| 70% | 2.9 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.2 |

| 80% | 30.1 | 33.3 | 29.2 | 24.4 | 27.6 |

| 90% | 58.8 | 57.8 | 54.7 | 60.0 | 61.2 |

| 100% | 8.1 | 7.4 | 13.1 | 12.6 | 9.0 |

| Chemotherapya (%) | |||||

| Cisplatin alone | 15.4 | 15.6 | 14.6 | 14.1 | 14.9 |

| Concomitant low | 52.9 | 45.9 | 56.9 | 48.1 | 52.2 |

| Concomitant moderate or high | 31.6 | 38.5 | 28.5 | 37.8 | 32.8 |

aThe median cisplatin dose was 75 mg/m2 for each group.

efficacy

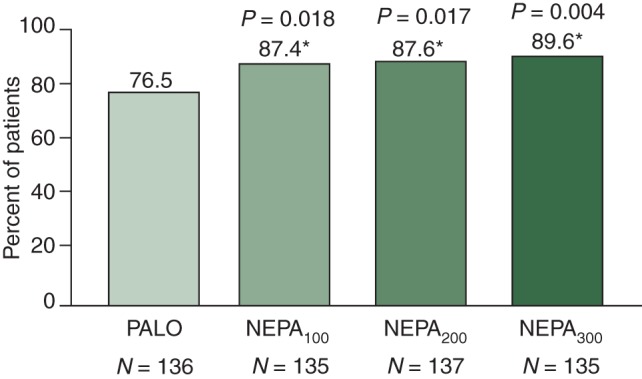

For the primary efficacy analysis, all NEPA dose groups showed superior CR rates compared with PALO during the overall phase (Figure 3). CR rates were also significantly higher for all NEPA groups compared with PALO during the delayed phase and significantly higher for NEPA300 during the acute phase.

Figure 3.

Primary analysis: complete response (no emesis and no rescue) (overall 0–120 h), *P-value from logistic regression versus PALO.

NEPA300 was more effective than PALO during all phases for secondary efficacy endpoints of no emesis, no significant nausea, and complete protection, while NEPA100 was superior to PALO for no emesis during the delayed/overall phases, and NEPA200 for no emesis and complete protection for delayed/overall phases and no significant nausea for the delayed phase. NEPA300 consistently demonstrated incremental clinical benefits over the two lower NEPA doses for all secondary efficacy endpoints (Table 2).

Table 2.

Efficacy endpoints

| Primary analyses (NEPA versus PALO) |

Exploratory analysis APR versus PALO |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PALO (N = 136) | NEPA100 (N = 135) | NEPA200 (N = 137) | NEPA300 (N = 135) | APR + OND (N = 134) | |

| Complete response (%) | |||||

| Acute (0–24 h) | 89.7 | 93.3 | 92.7 | 98.5%† | 94.8 |

| Delayed (25–120 h) | 80.1 | 90.4* | 91.2† | 90.4* | 88.8‡ |

| Overall (0–120 h) | 76.5 | 87.4* | 87.6* | 89.6† | 86.6‡ |

| No emesis (%) | |||||

| Acute | 89.7 | 93.3 | 92.7 | 98.5† | 94.8 |

| Delayed | 80.1 | 90.4* | 91.2† | 91.9† | 89.6‡ |

| Overall | 76.5 | 87.4* | 87.6* | 91.1† | 87.3‡ |

| No significant nausea (%) | |||||

| Acute | 93.4 | 94.1 | 94.2 | 98.5* | 94.0 |

| Delayed | 80.9 | 81.5 | 89.8* | 90.4† | 88.1 |

| Overall | 79.4 | 80.0 | 86.1 | 89.6* | 85.8 |

| Complete protection (%) | |||||

| Acute | 87.5 | 89.6 | 88.3 | 97.0† | 89.6 |

| Delayed | 73.5 | 80.0 | 87.6† | 84.4* | 82.1 |

| Overall | 69.9 | 76.3 | 80.3* | 83.0† | 78.4 |

†P ≤ 0.01 from logistic regression versus palonosetron; not adjusted for multiple comparisons, with exception of primary endpoint (CR overall).

*P ≤ 0.05 from logistic regression versus palonosetron; not adjusted for multiple comparisons, with exception of primary endpoint (CR overall).

‡P ≤ 0.05 from post hoc logistic regression versus palonosetron.

The CR rates were higher for males than for females; however, the incremental benefit of adding NETU to PALO existed for both genders with differences between the NEPA groups and PALO in overall CR ranging from 13.8% to 15.5% for females and 7.6% to 11.5% for males.

The exploratory APR arm showed higher CR and no emesis rates compared with PALO during the delayed/overall phases, but not the acute phase. While it showed numerically higher rates for no significant nausea and complete protection, these were not significantly different from PALO during any time post-chemotherapy. Although no formal comparisons were intended and differences were small, NEPA300 had numerically higher response rates than the multiday APR regimen for all the efficacy endpoints and time intervals.

safety

The overall incidence, type, frequency, and intensity of treatment-emergent adverse events were comparable across treatment groups. There was no evidence of a dose-related increase in these adverse events for the NEPA groups (Table 3). In total, 106 (15.6%) of the 679 patients experienced at least one treatment-related adverse event. The most common were hiccups and headache.

Table 3.

Summary of most common (≥2% incidence) treatment-related adverse events

| Adverse event n (%) | PALO (N = 136) | NEPA100 (N = 135) | NEPA200 (N = 138) | NEPA300 (N = 136) | APR + OND (N = 134) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with any adverse event | 67 (49.3) | 55 (40.7) | 71 (51.4) | 68 (50.0) | 71 (53.0) |

| Patients with any treatment-related adverse event | 17 (12.5) | 18 (13.3) | 24 (17.4) | 21 (15.4) | 26 (19.4) |

| Hiccups | 5 (3.7) | 5 (3.7) | 5 (3.6) | 7 (5.1) | 0 (0) |

| Headache | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.2) |

| Leukocytosis | 3 (2.2) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.2) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) |

| Dyspepsia | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (2.9) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) |

| Bradycardia | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.2) |

| Bundle branch block | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.2) | 0 (0) |

| Anorexia | 3 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) |

The majority (95%) of all adverse events were of mild/moderate intensity. Of the 33 (4.9%) patients who experienced a severe adverse event, 9 (1.3%) were considered to be related to study treatments (2 PALO, 3 NEPA200, and 4 APR).

Five patients (3 PALO, 1 NEPA100, and 1 NEPA200) had a serious adverse event. All but the NEPA200 patient (who experienced loss of consciousness) were deemed unrelated to study treatment. This patient recovered 30 min after onset; this was the only treatment-related adverse event leading to discontinuation. One patient (NEPA100) died during the study due to multiple organ failure. His death was not considered related to study medication.

Changes from baseline in 12-lead ECGs were consistent across treatment groups at each time point during the study. The percent of patients who developed treatment-emergent ECG abnormalities was comparable across groups.

discussion

This large, pivotal phase 2 study was designed to determine which of three dose combinations of NETU plus PALO would be most appropriate for continued development as a fixed-dose combination in the NEPA phase 3 clinical program.

For the primary analysis of CR during the overall phase, all NEPA groups showed superior CR rates compared with PALO alone. All NEPA dose groups also showed superior CR rates during the delayed phase; however, only NEPA300 was superior to PALO during the acute phase.

While the NEPA100 group may be the minimally effective dose based on the primary CR results, NEPA300 consistently showed an incremental clinical benefit over the lower NEPA doses for all secondary efficacy endpoints. Although these endpoints were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, NEPA300 was superior to PALO for no emesis, no significant nausea, and complete protection rates during all phases.

The CR rate in the PALO control arm was higher than the rates of CR noted in the control arm of earlier trials in HEC evaluating older 5-HT3 RAs with or without the addition of APR [10]. Despite the excellent control rates observed for the PALO control group, the magnitude of benefit associated with the NEPA regimens would still be considered to be clinically relevant (i.e. at least 10 absolute percentage points) during the acute/delayed/overall phases.

An exploratory APR-containing arm was included in this trial. The APR arm showed higher CR and no emesis rates compared with PALO during the delayed/overall phases. However, APR was not superior to PALO for CR during the acute phase, nor for no significant nausea and complete protection during any time post-chemotherapy.

NEPA arms showed a comparable safety profile to PALO and APR with a similar incidence of adverse events and ECG changes. The adverse event profile was consistent with that for an oncology patient population receiving HEC. All doses of NEPA were very well tolerated with no evidence of a dose response for adverse events, a very low incidence of serious events, and one unrelated death.

Despite the gratifying progress made over the past two decades in developing more effective means to prevent CINV, a number of significant challenges remain. As nausea remains a key issue in CINV control with all currently available agents [11], it is noted that NEPA300 was superior to PALO for the prevention of significant nausea. These results should encourage further studies with NEPA in which the control of nausea is the primary endpoint. In addition, certain higher risk groups (e.g. women, younger patients, and non-ethanol consumers) remain susceptible to CINV. While the CR rates were generally lower for females than males, the superiority of NEPA over PALO existed for both genders. While it is well established that implementation of antiemetic guidelines improves CINV control for patients, unfortunately, adherence to guidelines remains unacceptably low [1]. NEPA may improve guideline adherence by providing an all oral single pill of the guideline-recommended antiemetic drug combination for patients at higher risk for CINV. In doing so, NEPA offers the potential to improve effectiveness of antiemetic control without compromising efficacy or safety.

In conclusion, the NEPA antiemetic regimens significantly improved prevention of CINV in patients receiving cisplatin-based HEC. While all NEPA doses were highly effective and well tolerated, when considering all endpoints and time intervals, NEPA300 was the most effective dose combination. Based on these findings, the NEPA300 (NETU/PALO) fixed-dose combination was selected for continued development in the phase 3 program.

funding

This work was supported by Helsinn Healthcare, SA, who provided the study drugs and the funding for this study.

disclosure

The authors have the following conflicts of interest to disclose: PH: non-compensated consultant for Helsinn Healthcare. MP, G. Rossi, and G. Rizzi: employees of Helsinn Healthcare. RG: advisor for Merck, Helsinn Healthcare, and Eisai. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

acknowledgements

The authors thank the clinical investigators, patients, and site personnel who participated in the study. We acknowledge the editorial support of Jennifer Vanden Burgt during the writing of this manuscript, Silvia Olivari and Silvia Sebastiani from Helsinn Healthcare SA and Norman Nagl from Eisai Inc. for critically reviewing the manuscript, and the NEPA Publication Steering Committee (Drs Paul Hesketh, Richard Gralla, Matti Aapro, Karin Jordan, and Steven Grunberg) for their leadership and guidance. We express our sincere appreciation to the late Dr Steven Grunberg, our esteemed colleague whose contributions to supportive care and to this study were of great significance.

references

- 1.Feyer P, Jordan K. Update and new trends in antiemetic therapy: the continuing need for novel therapies. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:30–38. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rojas C, Slusher BS. Pharmacological mechanism of 5-HT3 and tachykinin NK-1 receptor antagonism to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;684:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gralla R, Lichinitser M, Van Der Vegt S, et al. Palonosetron improves prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: results of a double-blind randomized phase III trial comparing single doses of palonosetron with ondansetron. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1570–1577. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saito M, Aogi K, Sekine I, et al. Palonosetron plus dexamethasone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy: a double-blind, double-dummy randomized, comparative phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aapro MS, Grunberg SM, Manikhas GM, et al. A phase III, double-blind, randomized trial of palonosetron compared with ondansetron in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1441–1449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stathis M, Pietra C, Rojas C, et al. Inhibition of substance P-mediated responses in NG108–15 cells by netupitant and palonosetron exhibit synergistic effects. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;689:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spinelli T, Calcagnile S, Giuliano C., et al. Netupitant PET imaging and ADME studies in humans. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54(1):97–108. doi: 10.1002/jcph.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grunberg S, Voisin D, Zufferli M, et al. Oral palonosetron is as effective as intravenous palonosetron: a phase 3 dose ranging trial in patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2007;5 (Suppl 4): abstr 1143, p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boccia R, Grunberg S, Franco-Gonzales E, et al. Efficacy of oral palonosetron compared to intravenous palonosetron for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: a phase 3 trial. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1453–1460. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1691-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curran MP, Robinson DM. Aprepitant: a review of its use in the prevention of nausea and vomiting. Drugs. 2009;69:1853–1878. doi: 10.2165/11203680-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunberg SM, Warr D, Gralla RJ, et al. Evaluation of new antiemetic agents and definition of antineoplastic agent emetogenicity—state of the art. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(Suppl 1):S43–S47. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]