Abstract

Vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA) is a chronic and progressive medical condition common in postmenopausal women. Symptoms of VVA such as dyspareunia, vaginal dryness, irritation, and itching can negatively impact sexual function and quality of life. The REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey assessed knowledge about VVA and recorded attitudes about interactions with healthcare providers (HCPs) and available treatment options for VVA. The REVIVE survey identified unmet needs of women with VVA symptoms such as poor understanding of the condition, poor communication with HCPs despite the presence of vaginal symptoms, and concerns about the safety, convenience, and efficacy of available VVA treatments. HCPs can address these unmet needs by proactively identifying patients with VVA and educating them about the condition as well as discussing treatment preferences and available therapies for VVA.

Keywords: postmenopausal, REVIVE survey, treatment strategies, vulvar and vaginal atrophy

Introduction

Vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA), resulting from the loss of estrogen stimulation on vaginal and vulvar tissue, is a common medical condition in postmenopausal women—one that will occur in most postmenopausal women at some point in their lives.1,2 There are an estimated 64 million postmenopausal women in the United States (US), and as many as 32 million women may suffer from VVA symptoms including dyspareunia (pain during sexual intercourse), vaginal dryness, and vaginal irritation.1,3,4 VVA is chronic, progressive, and, unlike vasomotor symptoms, will not resolve with time and without treatment. Left untreated, VVA symptoms can not only cause discomfort but can also negatively impact women’s quality of life, including sexual relationships and emotional well-being.1,5 Severe VVA may affect other quality-of-life aspects, including clothing choices, exercise options, and general pelvic floor comfort.

The recently published REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey, administered to a large cohort of postmenopausal women in the US, offers many insights into the impact of VVA symptoms on women’s lives. Findings of generally poor understanding of VVA among women, coupled with concerns about efficacy, convenience, and safety of vaginal over-the-counter (OTC) products and prescription therapies for VVA, emphasize the need for better communication between women and their healthcare providers (HCPs) about VVA and its treatment options.6

This article reviews findings from the REVIVE survey, discusses implications of these findings for HCPs who care for postmenopausal women, and provides practical treatment strategies for the care of women with VVA.

What Does the REVIVE Survey Tell us About VVA?

The REVIVE survey was an online evaluation of postmenopausal women in the US, conducted from May 31, 2012 through June 14, 2012, and published online on May 16, 2013.6 A total of 15,576 women aged 45–75 years were contacted through KnowledgePanel® (GfK Custom Research, Princeton, NJ), a demographically representative panel of US citizens, making the REVIVE survey the largest study cohort of postmenopausal women in recent years. Of 10,486 women who responded, 8081 (77%) identified themselves as postmenopausal (ie, having no menstrual period for the previous 12 months for natural or surgical reasons). Among 8081 postmenopausal women, 3046 (38%) reported ≤1 symptom consistent with VVA (dyspareunia, vaginal dryness, local irritation, tenderness, bleeding with sexual activity, or pain with exercise).

Knowledge/awareness of VVA

The common medical terms VVA and vulvar and vaginal atrophy were unfamiliar to most women reporting VVA symptoms. Most women were unaware that their vaginal symptoms could caused by menopause or hormonal changes; only approximately one-quarter of women specifically identified menopause as the cause of their symptoms.6 Thus, the REVIVE survey demonstrates that many postmenopausal women have low awareness and poor understanding of VVA and its associated symptoms. These findings show the contrast between perceptions of VVA symptoms and other symptoms that are more readily associated with menopause (eg, hot flushes). Women who associate VVA with menopause may assume that it will abate over time, similar to vasomotor symptoms.

Almost half of the study population had never discussed their VVA symptoms with an HCP. Forty percent of women with VVA symptoms said they expected HCPs to initiate this conversation; however, among those who had discussed VVA symptoms, the HCP was the initiator only 13% of the time. Similarly, among participants who had an HCP for gynecologic needs, only 19% reported being asked about sexual health during routine examination. The most common reasons for not mentioning symptoms to HCPs were the assumption that their symptoms were a natural part of aging or were not bothersome enough at that time.6

Among women who initiated discussions about VVA, 73% waited until a scheduled physical examination and ~50% waited greater than 7 months to do so.6 The most common symptoms prompting a visit specifically to discuss VVA were vaginal irritation (50%), dyspareunia (27%), and vaginal dryness (24%). Among women who discussed VVA symptoms with an HCP, ~50% felt neutral or negative about the information and recommended treatment options they received.6 This inadequate understanding of VVA, along with poor communication between women and their HCPs regarding VVA, may contribute to delayed diagnosis and treatment.

VVA symptoms and their impact on women’s lives

Data from the REVIVE survey demonstrate the considerable impact of VVA on women’s lives. The most commonly reported VVA symptoms among postmenopausal women were vaginal dryness (55%), dyspareunia (44%), and local irritation (37%) (Table 1).6 More than half of participants reported that VVA had the greatest impact on enjoyment of sex (Table 2). In all, 12% of women without a sexual partner noted they were not seeking one because of discomfort caused by their VVA symptoms. Approximately one in four women reported that other areas of their life were negatively affected by VVA, including sleep, general enjoyment of life, and temperament.

Table 1.

Symptoms of VVA reported by REVIVE participants.

| SYMPTOM | PARTICIPANTS IN REVIVE REPORTING SYMPTOM OF VVA |

|---|---|

| Vaginal dryness | 55% |

| Pain during intercourse (dyspareunia) | 44% |

| Vaginal irritation | 37% |

| Vaginal tenderness | 17% |

| Bleeding during intercourse | 8% |

| Pain during exercise | 2% |

Abbreviations: REVIVE, REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal Changes; VVA, vulvar and vaginal atrophy.

Table 2.

Percentage of women reporting interference because of vulvar and vaginal symptoms.6

| ACTIVITY | PERCENT OF WOMEN REPORTING INTERFERENCE |

|---|---|

| Enjoyment of sexual intercourse | 63% |

| Sense of sexual spontaneity | 55% |

| Ability to be intimate | 54% |

| Relationship with your significant other | 45% |

| Sleeping | 29% |

| Enjoyment of life in general | 27% |

| Temperament (personality traits) | 26% |

| Seeking a new intimate relationship | 13% |

| Traveling | 13% |

| Athletic activities (eg, playing tennis, running, riding a bicycle) | 12% |

| Everyday activities (eg, grocery shopping, cleaning up the house) | 11% |

| Participating in social activities | 10% |

| Ability to work (eg, at a job, volunteering) | 7% |

Although some participants in the REVIVE survey stated that the earliest onset of VVA symptoms was premenopause (13%), or during the first year after their last menstrual period (20%), most (67%) reported that their earliest symptoms began during postmenopause (greater than one year after their last menstrual period).6 The onset of individual symptoms occurred at variable times, with irritation being the most likely symptom occurring premenopause, and dryness or tenderness more likely to begin during the first year after cessation of menstrual periods.

Women’s use of VVA treatments

Use of VVA-specific treatments (vaginal OTC products [eg, Astroglide® and Replens®] or vaginal prescription therapies [eg, Estrace®, Vagifem®, and Estring®]) was reported by 40% of participants.6 OTC products were used by 67% of those who ever used a treatment, and vaginal estrogen therapies were used by 27%. Even among women who had discussed symptoms with an HCP, the use of OTC products as monotherapy was common (62%); 23% of women who had spoken with an HCP were on prescription therapy and 15% of women were using vaginal prescription therapy + OTC vaginal therapy. Reported limitations of participants’ current OTC or prescription treatments included inadequate symptom relief, inconvenience, and dislike of the accommodations needed for vaginal administration (ie, privacy and nighttime administration).

Women’s likes and dislikes of current VVA treatments

Previous population-based surveys7–10 have identified that many women who are using vaginal therapies to treat their VVA symptoms are dissatisfied and discontinue treatment because they had concerns about side effects, or had found the treatment messy and inconvenient or not to have an effect on their symptoms. An additional analysis of data collected in the REVIVE survey6 looked at women’s perspectives on their satisfaction/dissatisfaction with their current treatments for VVA including OTC lubricants and moisturizers as well as prescription vaginal estrogen therapies.

Of the 3046 postmenopausal women in the REVIVE survey who reported VVA symptoms, 41% were currently using some form of treatment for VVA. However, of those women who actually had been given a clinical diagnosis of VVA (9% recalled being given a diagnosis), 27% were not using any treatment for their symptoms—neither a prescription nor OTC treatment. Only 35% of postmenopausal women currently on any treatment for VVA (OTC, prescription vaginal estrogens, or both) were satisfied with their current VVA treatment, with women using vaginal estrogen generally more satisfied than women using OTC lubricants or moisturizers (42% vs. 32%, respectively). In the assessment of dislikes among current treatment options, long-term safety (41%) was identified as a major concern for users of vaginal estrogen therapies. Messiness (43%) was the major concern identified by users of OTC lubricants or moisturizers (Table 3). Many women recognized that OTC lubricants or moisturizers were able to neither restore the vagina to its natural state (39%) nor provide adequate relief of VVA symptoms (28%). For the women who remained naïve to treatment despite a diagnosis of VVA, major concerns for not initiating treatment included safety concerns (28%) and concerns about hormone exposure (16%). However, many of these women (44%) felt their symptoms were not bothersome enough to warrant treatment.

Table 3.

Concerns and dislikes of current treatments for VVA.

| TOP CONCERNS AND DISLIKES REGARDING CURRENTLY AVAILABLE TREATMENTS FOR VULVAR AND VAGINAL ATROPHY | ||

|---|---|---|

| OTC LUBRICANTS OR MOISTURIZERS (n = 1227) | VAGINAL ESTROGEN (n = 409) | NEVER USED OTC LUBRICANTS OR MOISTURIZERS OR VAGINAL ESTROGEN (n = 788) |

| Messiness (43%) | Long-term safety (41%) | Symptoms not bothersome enough (44%) |

| Vagina not restored to natural (39%) | Vagina not restored to natural (36%) | Assumed symptoms would go away (30%) |

| Lack of symptom relief (28%) | Concerns regarding hormone exposure (35%) | Concerns regarding side effects (28%) |

| Loss of sexual spontaneity (23%) | Cost (31%) | Lack of symptom relief (23%) |

| Issues of administration (23%) | Concerns regarding breast cancer (29%) | Issues of administration (21%) |

| Inconvenience (17%) | Risk of side effects (26%) | Inconvenience (17%) |

| Lack of privacy (11%) | Lack of symptom relief (23%) | Concerns regarding hormone exposure (16%) |

| Vaginal discharge (10%) | Issues of administration (21%) | Risk of side effects (13%) |

| Vaginal delivery (9%) | Messiness (19%) | Concerns regarding breast cancer (10%) |

| Cost (8%) | Inconvenience (18%) | Messiness (7%) |

With regard to satisfaction with current treatment(s), 40% of those using vaginal estrogen therapy felt they had no other treatment option, with an additional 22% feeling inconvenienced with the mode of administration. In addition, 38% of all women who had ever used prescription products to treat VVA chose not to refill their vaginal estrogen therapy because of a variety of concerns related to safety or side effects (45%) including long-term safety concerns (28%), administration (8%), messiness (15%), or overall treatment efficacy (47%), with 16% citing “not enough relief from VVA symptoms.” Similar concerns were raised by those women who discontinued the use of OTC lubricants and moisturizers, including issues related to administration (10%), messiness (14%), and overall treatment efficacy (38%). Some women also stated the symptoms not being bothersome enough as a reason for discontinuing their current therapy (OTC, 9%; vaginal estrogen, 14%).

When asked about preferences regarding the method of treatment for their VVA symptoms, 39% indicated that they would prefer an oral pill and 31% vaginal treatment. An oral treatment was highly preferred among younger patients as well as those patients who had never used any VVA treatment, especially among those who indicated a direct preference. For those women currently using any type of treatment for their VVA symptoms, there was no difference in preference between an oral treatment (35%) or a vaginal treatment (41%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Reported preference for oral or vaginal administration.

| TOTAL (n = 3046) | AGE 45–55 YEARS (n = 814) | AGE 56–65 YEARS (n = 1425) | AGE 66–75 YEARS (n = 807) | CURRENT USERS (n = 1266) | LAPSED USERS (n = 989) | NAÏVE USERS (n = 788) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefer an orally administered treatment | 39% | 46% | 35% | 36% | 35% | 36% | 47% |

| No direct preference for either administration method | 28% | 29% | 28% | 27% | 23% | 31% | 32% |

| Prefer a vaginally administered treatment | 31% | 23% | 35% | 35% | 41% | 31% | 18% |

Management of VVA

Results of the REVIVE survey verify that many women suffering from VVA symptoms do not discuss them with their HCP. They may find it easier to discuss hot flushes rather than vaginal symptoms such as painful sex, because of the sensitivity of the latter topic.11 However, even women who have discussed VVA with their HCP may not have had an optimal experience, as illustrated by the high number of women who continue using OTC products despite inadequate symptom relief. Bridging communication gaps in the difficult topics of sexual health and menopause can result in increased patient adherence and satisfaction with VVA treatment. This can be accomplished not only by physicians but also by HCPs in gyn and primary care practices such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants who may have more opportunity to engage in in-depth discussions and provide individualized care.12,13

When a potentially uncomfortable topic arises, a key to fostering open communication is to first put the woman at ease by “normalizing” the conversation, commenting that VVA is a common medical condition that most postmenopausal women experience. This can often be accomplished by prefacing questions about VVA with general broad statements such as “Many women have vaginal changes after menopause, so I ask all of my patients about vaginal and sexual health,” or “It is common for menopausal women to have vaginal changes after menopause. Tell me if you have experienced symptoms of vaginal changes, such as dryness.” Opening statements such as these can be followed by more specific questions about bothersome vaginal symptoms.11,14,15 Willingness to discuss these issues can even be facilitated in the waiting room by providing a comfortable environment and pamphlets or other materials addressing the topic.

The gynecologic examination can also serve as a trigger for discussion. If signs of VVA are present, although the patients did not complain of any symptoms, a statement can be made such as “I notice some changes that I’ve seen in many postmenopausal women that may cause symptoms such as vaginal dryness or pain with intercourse,” followed by “Tell me about any symptoms you may have experienced.” Simple screening questions can be incorporated into routine visits for women in their mid-40s to facilitate an open and honest dialogue about VVA and the potential negative impact of VVA symptoms. The goal is to identify women who are experiencing VVA symptoms but have not mentioned them because of assumptions and misconceptions such as those revealed in the REVIVE survey.

Before the publication of the Women’s Health Initiative study, hormone therapy was prevalent and may have inadvertently treated VVA in women receiving this therapy for other menopausal symptoms. However, the utilization and acceptance of systemic hormone replacement therapy is currently low,16 resulting in more women presenting with VVA symptoms. With the trend toward using the lowest possible hormone dose for the shortest possible time, VVA can even occur among postmenopausal women who are taking systemic hormone therapy.17 Furthermore, as shown by the REVIVE survey, women often do not understand that VVA is related to menopause. Effective patient education might begin with the explanation that VVA is a common medical condition associated with reduced estrogen levels after menopause, though less well known than vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes). At the same time, HCPs should point out that, unlike hot flushes, VVA will worsen over time if left untreated.1 Findings from the REVIVE survey indicate that, for some women, symptom onset may occur at early stages of menopause and postmenopause; these women may experience VVA symptoms for a prolonged period if treatment is not initiated as soon as symptoms appear.

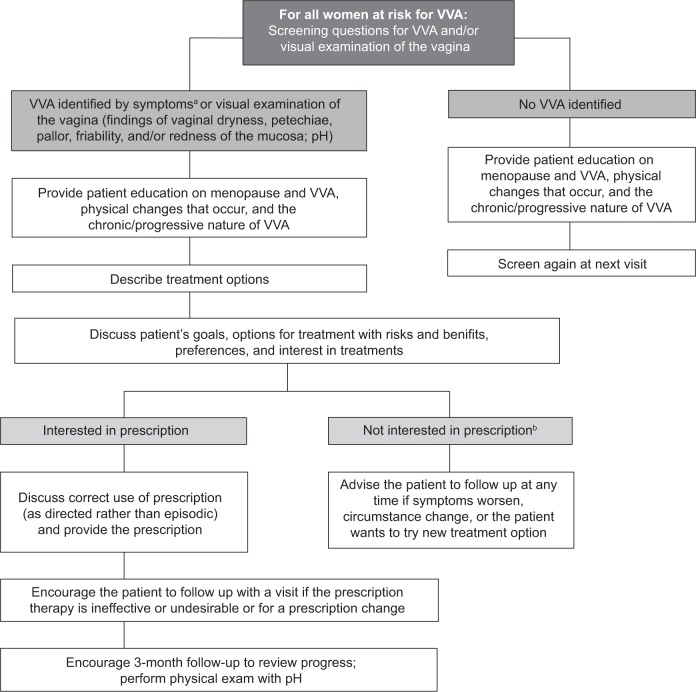

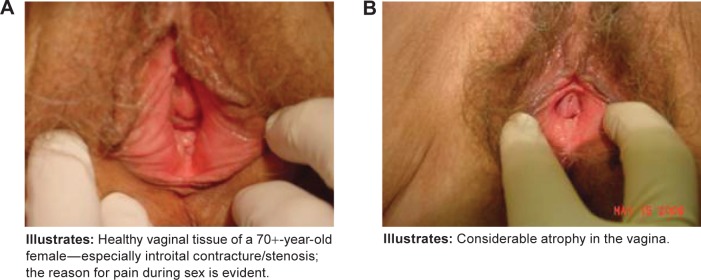

Additionally, it may be helpful to describe the physical changes occurring in the vaginal tissues that result in VVA and how these changes lead to the symptoms that women experience. Changes in the number of superficial and parabasal cells in the vagina lead to reduced moisture and elasticity, which contribute to symptoms such as vaginal dryness and dyspareunia. Increases in vaginal pH lead to greater susceptibility to infection, which in turn can produce symptoms such as itching and irritation. Visual examination findings, such as vaginal dryness, petechiae, pallor, friability, and redness of the mucosa, may also prompt discussion of menopausal vaginal changes (Fig. 1). An effective way to describe these changes to patients may be as follows: “Before menopause, due to the presence of estrogen, the vagina is moist and has ridges and folds, like pleats, that allow the vagina to be more flexible and adaptable for intercourse and childbirth. Without estrogen, physical changes occur in the vagina, leading to symptoms such as painful sex and dryness, and the chemistry of the vagina changes, resulting in greater likelihood of infection, itching, and irritation.” A suggested approach to screening and managing VVA and associated symptoms is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Images of (A) healthy vaginal tissue and (B) atrophic vaginal tissue.

Figure 2.

Suggested approach to treating postmenopausal women at risk for VVA.

Notes: aConfirmed by visual examination of the vagina. bIf OTC products are tried initially, consider providing a prescription that the patient can have on hand if the OTC products are found to be inadequate; this may help to avoid a delay in treatment.

Another important point to emphasize during patient education is that OTC products do not effectively treat the underlying pathological causes of VVA and therefore do not halt or reverse the progression of this condition. However, certain prescription therapies (ie, estrogens and estrogen agonist/antagonist therapies) directly improve the physical changes underlying VVA by increasing superficial cells and reducing parabasal cells and vaginal pH. Although OTC products may be the reasonable first-line option for women with mild symptoms, it would be proactive to provide a prescription at the time of diagnosis. Thus, if the OTC product is tried and found to be ineffective, as was the case for ~40% of the REVIVE survey participants who used them, the patient would already have a prescription in hand, and thus treatment would not have to be delayed.

Women should be counseled on the many treatment options available for VVA-related symptoms,18 and they can make choices based on their personal preferences and needs. Treatment adherence is improved when women participate in the decision-making process. Table 5 provides an overview of currently available options for VVA, including OTC products (lubricants and moisturizers), vaginal estrogen therapies (conjugated equine estrogen and estradiol creams, estradiol tablet and ring), and a new non-estrogen oral therapy, ospemifene, which is an estrogen agonist/antagonist recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal VVA.

Table 5.

VVA-specific OTC and prescription treatments.

| TYPE | ROUTE | DOSING | ACTION | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over-the-Counter | |||||

| Water- and silicone-based lubricants19–21 | Topical: Vulva and vagina | Applied to vagina and vulva before sexual activity | Reduces friction from sexual activity | Local application to the affected area | Does not treat the underlying progressive condition of VVA, no long-term therapeutic effect, inconvenient application. |

| Moisturizers19–22 | Topical: Vulva and vagina | Regularly scheduled application (every 1–3 days) as needed for dryness | Replaces vaginal secretions | Non-hormonal | Does not treat the underlying progressive condition of VVA, no long-term therapeutic effect, inconvenient application. |

| Prescription | |||||

| Estrogen cream (conjugated equine estrogens or estradiol)22–29 | Vaginal | Daily for 2 weeks, then twice weekly as needed | Estrogen delivery to the local affected area | Treats underlying changesa Cream allows for some application to introitus to “prime” the tissue use of intra-vaginal applications | Application requires privacy concern regarding systemic absorption of estrogen for women at risk of breast cancer or venous thromboembolism. |

| Estrogen ring (estradiol)24 | Vaginal | Replace 1 ring every 3 months | Estrogen delivery to the local affected area | Treats underlying changesa Three month use eliminates the need for remembering schedule of weekly use | Difficult to insert for women with moderate to severe atrophy. Concerns regarding systemic absorption of estrogen for women at risk of breast cancer or venous thromboembolism. |

| Estrogen tablet (estradiol hemihydrate)27,28,30 | Vaginal | Daily for 2 weeks, then twice weekly as needed | Estrogen delivery to the local affected area | Treats underlying changesa | Application requires privacy concern regarding systemic absorption of estrogen for women at risk of breast cancer or venous thromboembolism. |

| Estrogen agonist/antagonist (ospemifene)31–34 | Oral | Daily | Binds to estrogen receptors, resulting in tissue-selective estrogen agonist or antagonist effects | Treats underlying changesa Oral administration | Systemic exposure may be associated with increased risk of certain adverse events. Should be prescribed for the shortest duration consistent with treatment goals and risk for the individual woman. |

Note:

“Treats underlying changes” indicates that it increases the number of vaginal superficial cells, decreases the number of parabasal cells, decreases vaginal pH, and provides improvement in visual examination parameters (such as vaginal dryness, petechiae, pallor, friability, and redness of the mucosa).

Abbreviation: VVA, vulvar and vaginal atrophy.

Conclusions

The REVIVE survey offers important insights on VVA from postmenopausal women experiencing undesirable vaginal symptoms. This survey illustrates that women’s awareness/understanding of VVA is low, and almost half of the REVIVE survey participants had not discussed their vaginal symptoms with their HCP. Moreover, 40% of women expected their HCP to initiate a conversation about menopausal symptoms. These findings underscore the need for increased vigilance by HCPs caring for postmenopausal women. For women approaching menopause, simple screening questions about vaginal symptoms can be asked during routine visits, and the responses can help identify those in need of treatment. In addition, proactive patient education can be provided on the physical changes underlying VVA and how the condition can progress if left untreated.

The REVIVE survey also provides important information on limitations of current treatments for VVA. Most women were untreated despite continuation of their bothersome symptoms. Only 41% of respondents were current treatment users, whereas 27% had never been treated and 33% had stopped using treatment. The use of OTC products that do not treat the physiological changes underlying VVA was prevalent, even among women who had discussed their symptoms with an HCP. Respondents also identified barriers to vaginal estrogen therapies. Nurse Practitioners (NPs) should engage their patients in a candid discussion of symptom severity, preferences, and concerns regarding VVA treatments. This approach can help guide treatment selection and patient education, which ultimately may improve patient adherence and outcomes.

The REVIVE survey exposes many issues in the current management of VVA. HCPs are in a position to proactively identify women suffering from VVA, provide essential patient education regarding the condition, and guide their patients to appropriate treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Elizabeth Downs, Philip Sjostedt, and The Medicine Group for editorial assistance in the development of this manuscript, funded by Shionogi Inc. All authors had full control over the REVIVE survey and the survey questions, and took full responsibility for the development of the content of this article.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS: SW receives financial support from Bayer HealthCare, Johnson & Johnson, TEVA, Novo Nordisk, Merck, Church and Dwight, Watson, and Shionogi Inc. for participation in review activities such as data monitoring boards, statistical analysis, and end point committees. She also receives support from Bayer HealthCare, TEVA, Novo Nordisk, Watson, Pfizer, and Merck for lecturing and service on speakers’ bureaus. SK receives financial support from Shionogi Inc., Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer as a member of the board, for consultancy and development of educational presentations, and for travels/accommodations/meeting expenses. MK receives financial support or honoraria from Shionogi Inc., Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, Viveve, and Sprout for consultancy, and from Palatin for participation in review activities such as data monitoring boards, statistical analysis, and end point committees. In the past, he received support from Warner Chilcott for lecturing and service on speakers’ bureaus.

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Zeev Blumenfeld, Editor in Chief

This paper was subject to independent, expert peer review by a minimum of two blind peer reviewers. All editorial decisions were made by the independent academic editor. All authors have provided signed confirmation of their compliance with ethical and legal obligations including (but not limited to) use of any copyrighted material, compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests disclosure guidelines and, where applicable, compliance with legal and ethical guidelines on human and animal research participants.

Author Contributions

SW, SK, and MK each contributed to the concept, design, drafting, critical revisions, and approval of the article. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

FUNDING: Medical writing support was funded by Shionogi Inc. The funders had no influence over the content of the REVIVE Survey or of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.The North American Menopause Society Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20(9):888–902. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182a122c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston SL, Farrell SA, Bouchard C, et al. The detection and management of vaginal atrophy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004;26(5):503–515. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Commerce . Age and sex composition: 2010. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; (Report No.: C2010BR-03-2011). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gass ML, Cochrane BB, Larson JC, et al. Patterns and predictors of sexual activity among women in the hormone therapy trials of the Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause. 2011;18(11):1160–1171. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182227ebd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281(6):537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) Survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1790–1799. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.REVEAL . REVEAL: REvealing Vaginal Effects At mid-Life. Surveys of Postmenopausal Women and Health Care Professionals Who Treat Postmenopausal Women; 2009. [Accessed January 3, 2013]. Available at: www.revealsurvey.com/pdf/reveal-survey-results.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman M, Reape KZ, Giblin K. Impact of menopausal symptoms on sex lives: a survey evaluation [abstract presented at the North American Menopause Society 2007 conference] Menopause. 2007;14(6):1107. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nappi R, Maamari R, Simon J. The partners’ survey: implications of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy for women and their partners. Maturitas. 2012;71:S64. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2009;6(8):2133–2142. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz A. When sex hurts: menopause-related dyspareunia. Vaginal dryness and atrophy can be treated. Am J Nurs. 2007;107(7):34–36. 39. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000279264.66906.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theroux R. Women’s decision making during the menopausal transition. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2010;22(11):612–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sturdee DW, Panay N. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2010;13(6):509–522. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.522875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kingsberg S, Kellogg S, Krychman M. Treating dyspareunia caused by vaginal atrophy: a review of treatment options using vaginal estrogen therapy. Int J Womens Health. 2009;1:105–111. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pillai-Friedman S. Patient barriers to communication about female sexual health. [Accessed date 12-4-2012].

- 16.Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Cronin KA. A sustained decline in postmenopausal hormone use: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(3):595–603. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318265df42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Indhavivadhana S, Leerasiri P, Rattanachaiyanont M, et al. Vaginal atrophy and sexual dysfunction in current users of systemic postmenopausal hormone therapy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93(6):667–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan O, Bradshaw K, Carr BR. Management of vulvovaginal atrophy-related sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women: an up-to-date review. Menopause. 2012;19(1):109–117. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31821f92df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bygdeman M, Swahn ML. Replens versus dienoestrol cream in the symptomatic treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1996;23(3):259–263. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00955-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YK, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, Kang SB. Vaginal pH-balanced gel for the control of atrophic vaginitis among breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):922–927. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182118790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nachtigall LE. Comparative study: Replens versus local estrogen in menopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1994;61(1):178–180. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biglia N, Peano E, Sgandurra P, et al. Low-dose vaginal estrogens or vaginal moisturizer in breast cancer survivors with urogenital atrophy: a preliminary study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26(6):404–412. doi: 10.3109/09513591003632258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long CY, Liu CM, Hsu SC, Chen YH, Wu CH, Tsai EM. A randomized comparative study of the effects of oral and topical estrogen therapy on the lower urinary tract of hysterectomized postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(1):155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayton RA, Darling GM, Murkies AL, et al. A comparative study of safety and efficacy of continuous low dose oestradiol released from a vaginal ring compared with conjugated equine oestrogen vaginal cream in the treatment of postmenopausal urogenital atrophy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103(4):351–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachmann G, Bouchard C, Hoppe D, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose regimens of conjugated estrogens cream administered vaginally. Menopause. 2009;16(4):719–727. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a48c4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kendall A, Dowsett M, Folkerd E, Smith I. Caution: vaginal estradiol appears to be contraindicated in postmenopausal women on adjuvant aromatase inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(4):584–587. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manonai J, Theppisai U, Suthutvoravut S, Udomsubpayakul U, Chittacharoen A. The effect of estradiol vaginal tablet and conjugated estrogen cream on urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women: a comparative study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2001;27(5):255–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2001.tb01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rioux JE, Devlin C, Gelfand MM, Steinberg WM, Hepburn DS. 17beta-estradiol vaginal tablet versus conjugated equine estrogen vaginal cream to relieve menopausal atrophic vaginitis. Menopause. 2000;7(3):156–161. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200007030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santen RJ, Pinkerton JV, Conaway M, et al. Treatment of urogenital atrophy with low-dose estradiol: preliminary results. Menopause. 2002;9(3):179–187. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eugster-Hausmann M, Waitzinger J, Lehnick D. Minimized estradiol absorption with ultra-low-dose 10 microg 17beta-estradiol vaginal tablets. Climacteric. 2010;13(3):219–227. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.483297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bachmann GA, Komi JO. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17(3):480–486. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181c1ac01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Portman DJ, Bachmann G, Simon J, The Ospemifene Study Group Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2013;20(6):623–630. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318279ba64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon JA, Lin VH, Radovich C, Bachmann GA, The Ospemifene Study Group One-year long-term safety extension study of ospemifene for the treatment of vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women with a uterus. Menopause. 2013;20(4):418–427. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31826d36ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wurz GT, Soe LH, DeGregorio MW. Ospemifene, vulvovaginal atrophy, and breast cancer. Maturitas. 2013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]