Abstract

In plants, abscission removes senescent, injured, infected, or dispensable organs. Induced by auxin depletion and an ethylene burst, abscission requires pronounced changes in gene expression, including genes for cell separation enzymes and regulators of signal transduction and transcription. However, the understanding of the molecular basis of this regulation remains incomplete. To examine gene regulation in abscission, this study examined an ERF family transcription factor, tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) ETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE FACTOR 52 (SlERF52). SlERF52 is specifically expressed in pedicel abscission zones (AZs) and SlERF52 expression is suppressed in plants with impaired function of MACROCALYX and JOINTLESS, which regulate pedicel AZ development. RNA interference was used to knock down SlERF52 expression to show that SlERF52 functions in flower pedicel abscission. When treated with an abscission-inducing stimulus, the SlERF52-suppressed plants showed a significant delay in flower abscission compared with wild type. They also showed reduced upregulation of the genes for the abscission-associated enzymes cellulase and polygalacturonase. SlERF52 suppression also affected gene expression before the abscission stimulus, inhibiting the expression of pedicel AZ-specific transcription factor genes, such as the tomato WUSCHEL homologue, GOBLET, and Lateral suppressor, which may regulate meristematic activities in pedicel AZs. These results suggest that SlERF52 plays a pivotal role in transcriptional regulation in pedicel AZs at both pre-abscission and abscission stages.

Key words: Abscission, abscission zone, cell-wall hydrolytic enzyme, ERF, functional switching, meristem, tomato, transcription activator, transcription factor.

Introduction

In plants, organ abscission specifically detaches senescent, injured, infected, or dispensable leaves or flower organs to maintain the healthy growth of the main body. Abscission also detaches mature seeds or fruits to disperse the plant’s progeny. To abscise an organ, plants generally develop a specialized tissue, the abscission zone (AZ), at a predetermined site on the organ to be abscised. Under normal conditions, the AZ firmly attaches the organ to the plant body; after initiation of abscission, the AZ tissues weaken, allowing the organ to detach. Plant hormones act in opposition to regulate organ separation: ethylene promotes abscission and auxin inhibits abscission, in an ethylene-antagonistic manner (Taylor and Whitelaw, 2001; Meir et al., 2010). Abscission involves the activation of cell-wall-degradation machinery in the AZ, including cell-wall hydrolytic enzymes such as endo-β-1,4-glucanase (also referred as cellulase (Cel)), polygalacturonase (PG), expansin, and xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (Roberts et al., 2002; Nakano and Ito, 2013). These enzymes degrade the primary cell wall or middle lamella pectin of AZ tissues so that abscising organs detach easily from the parent plant. Marked changes in transcription activate cell-wall degradation and other abscission processes (Meir et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013); therefore, unveiling the mechanisms of transcriptional regulation will enable a more clear understanding of the onset of abscission. In Arabidopsis thaliana, various transcription factors (TFs) positively or negatively regulate abscission of floral organs, including stamens, petals, and sepals. These TFs include members of the KNOTTED-LIKE HOMEOBOX (KNOX) family, the DNA BINDING WITH ONE FINGER (DOF) family, the MADS-box family, the ETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE FACTOR (ERF) family, the AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR (ARF) family, and the ZINC FINGER family (Fernandez et al., 2000; Ellis et al., 2005; Cai and Lashbrook, 2008; Wei et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2011a,b ). However, the relationships among these TFs and the resulting transcriptional cascades remain incompletely understood.

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants develop AZs at the midpoint of the flower pedicels. The AZs have a knuckle-like structure with a groove on the surface. If pollination fails, the flower will senesce and eventually abscise from the plant at the AZ. During flower pedicel abscission, expression of PG and Cel greatly increases (Meir et al., 2010; Nakano et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013). Programmed cell death also occurs during flower pedicel abscission (Bar-Dror et al., 2011). In tomato, several mutations can inhibit development of pedicel AZs, causing a ‘jointless’ phenotype. For example, jointless (j) is a mutation of a MADS-box TF gene and lateral suppressor (ls) is a mutation of a GRAS family TF gene (Schumacher et al., 1999; Mao et al., 2000). The locus for another ‘jointless’ mutation, j-2, has not yet been identified, but a sequencing analysis has identified a candidate gene encoding C-terminal domain (CTD) phosphatase-like 1 (ToCPL1) (Yang et al., 2005). In addition, the current study group has showed that the MADS-box TF MACROCALYX (MC) regulates pedicel AZ development and that a heterodimer of MC and J functions as a unit for this regulation (Nakano et al., 2012). Recent work identified another tomato MADS-box TF gene, SlMBP21, as a regulator of pedicel AZ development and showed that the encoded protein also interacts with MC and J (Liu et al., 2014). To identify more genes involved in pedicel abscission, Nakano et al. (2012, 2013) identified genes that are regulated by both MC and J and are expressed specifically in pedicel AZs. Interestingly, the results of this screen suggested that the tomato WUSCHEL homologue (LeWUS), GOBLET (GOB), Ls, and BLIND (Bl), which regulate meristem activity, also regulate pedicel AZ activity. However, their detailed roles in AZs remain unknown. The screen also identified several other TF genes: OVATE, SlERF52, and a zinc finger-homeodomain (ZF-HD) family protein.

Based on the previous study, the current work focused on an ERF family TF gene, SlERF52. The ERF family TFs constitute one of the largest TF families in the plant kingdom (Riechmann et al., 2000); for example, the tomato genome includes at least 85 genes for ERF family proteins, most of which remain uncharacterized (Sharma et al., 2010). The ERF family members contain a single DNA-binding domain, the APETALA2 (AP2)/ERF domain (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1995), and, as monomers, recognize the GCC-box or CRT/DRE (for C-repeat/dehydration responsive element) cis-acting DNA elements (Allen et al., 1998; Hao et al., 1998; Yang et al., 2009). The AP2/ERF domain was identified in proteins binding to ethylene-responsive gene promoters (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1995), but subsequent studies revealed that the ERF family TFs function in diverse aspects of plant growth, development, and physiology, such as meristem activity, floral organ abscission, lipid metabolism, alkaloid biosynthesis, and responses to environmental stress (extreme temperature, water deficit, salinity, low oxygen, and pathogen infection) (Stockinger et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1998; Solano et al., 1998; van der Fits and Memelink, 2000; Banno et al., 2001; Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002; Gu et al., 2002; Kirch et al., 2003; Komatsu et al., 2003; Broun et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2006; Shoji et al., 2010; Iwase et al., 2011). The current study used gene suppression to investigate the function of SlERF52. The results demonstrate that SlERF52 is required for activation of cell-wall-degrading enzymes during abscission as well as pedicel-specific gene expression at the pre-abscission stage.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The tomato cultivar Ailsa Craig was used to make transgenic plants. The jointless mutant (TK3043) and the MC-suppressed transgenic plants were described previously (Nakano et al., 2012). Plants were grown in a controlled growth room under a 16/8 light/dark cycle at 25 °C.

Plasmid construction

Oligonucleotide primers used for gene amplification are listed in Supplementary Table S1 (available at JXB online). To obtain the SlERF52 gene fragments, cDNAs were synthesized from flower pedicel total RNA and used as templates for PCR amplification. A plasmid for RNA interference (RNAi) targeting SlERF52 was constructed as follows. A 315-bp fragment of SlERF52 was amplified with a pair of gene-specific primers, AK327476-F2 and AK327476-R2, and then cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO Gateway entry vector (Invitrogen). The cloned fragment was transferred into a binary vector for RNAi, pBI-sense, anti sense-GW (Inplanta Innovations, Japan) using Gateway LR Clonase Enzyme Mix (Invitrogen). The resultant plasmid was designated pBI-GW-SlERF52-RNAi.

Plasmids for the transactivation assay were constructed as follows. The full-length open reading frame of SlERF52 was amplified with the primer pair NcoI-SlERF52-F1 and BamHI-SlERF52-R1 and inserted into the NcoI and BamHI sites of pGBKT7 (Clontech), which carries an auxotrophic marker gene (TRP1). The resulting plasmid was designated pGBK-SlERF52. Sequencing analysis revealed that SlERF52 from Ailsa Craig possesses five single-nucleotide polymorphisms in comparison with the genome sequence of the cultivar Heinz 1706 (accession no. AB889741). A series of partial SIERF52 fragments were amplified using NcoI-SlERF52-F1 and BamHI-SlERF52-R2 for amino acids 1–74, NcoI-SlERF52-F1 and BamHI-SlERF52-R3 for amino acids 1–98, NcoI-SlERF52-F1 and BamHI-SlERF52-R4 for amino acids 1–133, and NdeI-SlERF52-C3 and BamHI-SlERF52-R1 for amino acids 133–162. Each amplified DNA fragment was inserted into pGBKT7, resulting in pGBKT7-SlERF521–74, pGBKT7-SlERF521–98, pGBKT7-SlERF521–133, and pGBKT7-SlERF52133–162, respectively.

Plant transformation

The plant transformation vector pBI-GW-SlERF52-RNAi was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 by the freeze–thaw method (Cindy and Jeff, 1994). Cotyledons of tomato seedlings were used for transformation by Agrobacterium infection according to the previously described method (Sun et al., 2006).

Transactivation assay

Transactivation assays in yeast cells were conducted according to the previously described method (Cho et al., 1999). The yeast strain AH109 (Clontech), which carries two auxotrophic marker genes (ADE2 for adenine biosynthesis and HIS3 for histidine biosynthesis) under the GAL4 cis-regulatory element, was used for the experiment. Yeast transformation was performed using the Frozen EZ Yeast Transformation II kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA), and transformants were selected on SD media lacking tryptophan (SD/–Trp, Clontech). Assays for transactivation activity were performed on SD media lacking tryptophan, adenine, and histidine (SD/–Trp/–Ade/–His). In the experiment, a target protein was expressed as a fusion protein with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (GAL4DBD), and if the protein had the potential to activate transcription, the auxotrophic marker genes (ADE2 and HIS3) were expressed and the yeast cell was able to grow on the adenine- and histidine-deficient selection medium.

Sequence analysis

Multiple sequence alignment was performed with ClustalW version 1.83 and the phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbour-joining method. GENETYX version 10 (GENETYX, Japan) was used for the analysis. Supplementary Table S2 shows the accession numbers for the sequences used in the analysis.

Reverse-transcription PCR and quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

Total RNAs were extracted using the RNeasy plus mini kit (Qiagen) in combination with the QIA shredder spin column (Qiagen). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript II 1st strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara Bio, Japan). PCR amplifications were performed using the ExTaq polymerase (Takara Bio). qRT-PCR was carried out with a 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR MIX (Toyobo, Japan). Data were normalized to the expression of the SAND gene (SGN-U316474) as an internal control (Exposito-Rodriguez et al., 2008). Relative quantification of expression of each gene was performed using the 2–ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Flower pedicel abscission assay

Flower pedicels were harvested at anthesis. The flower was removed from the pedicel using a sharp blade, the pedicel end was inserted into a 1.0% agar plate, and the plate was placed in a glass chamber to maintain high humidity. An abscission event was defined by pedicel detachment that occurred naturally or in a response to vibration applied to the distal portion of the explant.

Results

SlERF52 is a member of the ERF transcription factor family

As described previously, SlERF52 expression is strictly limited to the AZ region in the pedicel and SlERF52 expression is suppressed in plants that lack an AZ, namely MC-knockdown plants and j mutants (Nakano et al., 2012, 2013; Fig. 1A and B). No or very low expression of SlERF52 was detected in other organs, including roots, leaves, stems, flowers, sepals, and fruits (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that SlERF52 plays a specific role in pedicel abscission.

Fig. 1.

Expression specificity of SlERF52. (A) Expression analysis of SlERF52 in a jointless mutant, a MC-suppressed transgenic plant (AS-MC), and the wild type (WT). (B) Expression specificity of SlERF52 within flower pedicel parts, the distal (Dis), proximal (Prox), and abscission zone (AZ) regions in WT anthesis flowers. (C) Expression analysis of SlERF52 among various organs. Expression analysis was performed by reverse-transcription PCR using SAND (A and B) and SlActin-51 (C) as the internal control.

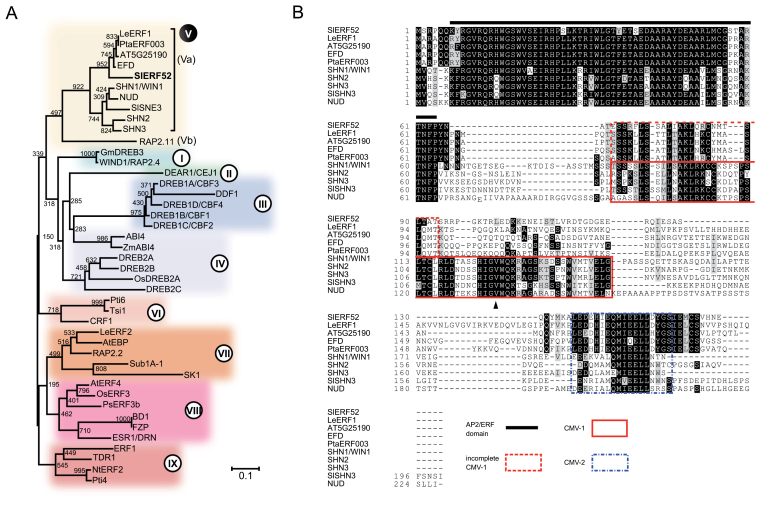

Phylogenetic analysis of the AP2/ERF domain revealed that SlERF52 belongs to group Va of ERFs (Fig. 2A). This group includes: Arabidopsis WAX INDUCER 1 (WIN1)/SHINE1 (SHN1), SHN2, and SHN3, which regulate cutin biosynthesis and abscission of floral organs (Aharoni et al., 2004; Broun et al., 2004; Shi et al., 2011b ); the tomato homologue of SHN3 (SlSHN3) (Shi et al., 2013); barley (Hordeum vulgare) NUDUM (NUD), which regulates lipid biosynthesis for hull-caryopsis adhesion of grain (Taketa et al., 2008); tomato LeERF1, which regulates ethylene signalling (Li et al., 2007); Medicago truncatula ERF REQUIRED FOR NODULE DIFFERENTIATION (EFD) (Vernie et al., 2008); and poplar (Populus tremula × P. alba) PtaERF003, which is involved in adventitious and lateral root formation (Trupiano et al., 2013). Group Va ERFs have three conserved domains: the AP2/ERF domain, conserved motif V (CMV)-1, and CMV-2 at the C-terminus (Fig. 2B). Group Va includes two subgroups, a subgroup with the normal CMV-1 domain (including WIN1/SHN1 and its orthologues), and another subgroup with an incomplete CMV-1 domain (including LeERF1, the AT5G15190-encoding protein, EFD, PtaERF003, and SlERF52; Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis and sequence alignment of SlERF52. (A) Phylogenetic relationships of SlERF52 with ERF proteins; the phylogenetic tree was constructed using amino acid sequences of the AP2/ERF domains in each ERF protein (Supplementary Table S2). (B) Multiple sequence alignment of group Va ERF proteins. Following the highly conserved AP2/ERF domain, there are two conserved motifs, CMV-1 and CMV-2 (Nakano et al., 2006). Based on the CMV-1 structure, the group Va ERFs are further classified into two subgroups: the normal CMV-1 subgroup including Arabidopsis SHNs, SlSHN3, and NUD and the incomplete CMV-1 subgroup including SlERF52, LeERF1, PtaERF003, AT5G25190, and EFD. The CMV-2 motif is conserved in both subgroups. Arrowhead indicates the amino acid substituted in the nud mutant (nud1.b; Taketa et al., 2008).

SlERF52 acts as a positive regulator of flower pedicel abscission

To analyse the biological role of SlERF52, RNAi was used to knock down SlERF52 expression. To that end, transgenic plants with an RNAi vector targeting SlERF52 were generated, 15 independent transgenic plants were obtained, and the three plants with the lowest expression levels of SlERF52 (plants 7, 18, and 20) were selected for further analysis (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. S1). The three SlERF52-suppressed plants appeared similar to wild-type plants and developed pedicel AZs normally (Fig. 3B), indicating that SlERF52 does not regulate differentiation of pedicel AZs. To examine the pedicel abscission behaviour of the transgenic plants, flower pedicel abscission was induced by removing the flower from the pedicel, which stimulates ethylene production and restricts auxin supply from the flower (Meir et al., 2010) and observing the frequency of abscission in the flower-removed pedicels for 3 d (Fig. 3C). The abscission frequency of pedicels from plants 7 and 20 at 3 d after flower removal was significantly lower than that of wild type, indicating that the pedicels of the two suppression lines showed decreased abscission potential compared to the wild type (Fig. 3D). The pedicels from plant 18 exhibited significant reduction of abscission frequency at 1 d after flower removal, although the abscission eventually occurred at the same level as the wild type at 3 d after flower removal (Fig. 3D). These observations indicate that the suppression of SlERF52 impaired activation of pedicel abscission.

Fig. 3.

Suppression of SlERF52 partially inhibited flower pedicel abscission. (A) Transcript levels of SlERF52 in three SlERF52-suppressed transgenic plants (plants 7, 18, and 20). Transcript level was examined in anthesis flower pedicels by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR. The levels are shown as fold-change values relative to that of WT; error bars indicate standard deviation of biological triplicates. (B) Suppression of SlERF52 did not affect pedicel abscission zone development. (C) Pedicel abscission was inhibited in the SlERF52-suppressed transgenic plants; arrows indicate the abscission zone. (D) Rate of flower pedicel abscission in SlERF52-suppressed transgenic plants. Pedicel abscission was induced by removing anthesis flowers. Asterisks indicate significant differences by chi-square test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, respectively; n=206 for WT, n=112 for plant 7, n=119 for plant 18, and n=110 for plant 20).

Suppression of SlERF52 inhibits induction of genes for cell-wall hydrolytic enzymes

Expression of genes encoding cell-wall hydrolytic enzymes, including PG and Cel, is induced in response to the abscission stimulus (Roberts et al., 2002). Because suppression of SlERF52 decreased the rate of pedicel abscission, the current work investigated whether it also affected the transcript levels of genes encoding PG (TAPG1, TAPG2, and TAPG4) and Cel (Cel1 and Cel5) during flower pedicel abscission. In accord with previous reports (Meir et al., 2010; Nakano et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013), in wild-type plants, removal of the flower induced the expression of TAPG1, TAPG2, TAPG4, Cel1, and Cel5 in AZs, but SlERF52 was expressed at constant levels before and after the onset of abscission (Fig. 4). In SlERF52-suppressed plants 7 and 20, TAPG1, TAPG2, TAPG4, and Cel5 were induced to significantly lower levels than in the wild type (Fig. 4), and the levels of these four genes corresponded to the abscission rates in the suppressed transformants (Fig. 3). The suppression was more severe for PG genes than for Cel5. Meanwhile, the levels of Cel1 expression did not correspond to the abscission rate.

Fig. 4.

Expression analysis in SlERF52-RNAi plants during abscission. Pedicel abscission was induced by anthesis flower removal and gene expression was investigated for 2 d by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR. For single RNA sample preparation, 3–24 pedicel abscission zones, which include both attached and abscised pedicels, were harvested in bulk and used for the analysis. Levels of transcripts are shown as fold-change values relative to the 0 d sample of WT (for Cel1, Cel5, TAPG4, SlERF52, Bl, GOB, LeWUS, and Ls). Because TAPG1 and TAPG2 transcript levels for the 0 d sample of WT were below detection limit (shown as ND), the level of the two genes are shown relative to the sample of SlERF52-suppressed plant 20 at 1 d. Data are mean±SD of biological triplicates.

Suppression of SlERF52 reduces expression of transcription factor genes LeWUS, GOB, and Ls in pedicel AZs

Previously, this study group reported that LeWUS, GOB, Ls, and Bl, four TF genes associated with shoot apical meristem or axillary meristem function, might also be involved in the regulation of pedicel AZ activity (Nakano et al., 2012, 2013). To investigate whether SlERF52 affects the expression of these four TF genes, their transcript levels in the SlERF52-suppressed plants were analysed. As observed previously, in wild-type plants, the expression of LeWUS, GOB, and Ls decreased markedly in response to flower removal, an abscission stimulus. In the SlERF52-suppressed plants, however, the transcript levels of these three genes were much lower than the wild type before flower removal (0 d) and their levels remained low after flower removal (1 d and 2 d) (Fig. 4). By contrast, the expression of Bl increased during abscission similarly in the SlERF52-suppressed plants and the wild type (Fig. 4). The transcript level of Bl in the suppressed plants was slightly lower than that in wild type throughout the examined period but the difference was not significant, except in the d-1 samples. The expression pattern of these four TF genes was not correlated with the expression of SlERF52 in shoot apices or leaf axillae of wild type plants and also was not affected by suppression of SlERF52 (Supplementary Fig. S2), which is consistent with the normal vegetative growth of the suppressed plants. The results suggest that the SlERF52-mediated regulation of LeWUS, GOB, and Ls is specific to pedicel AZs.

SlERF52 functions as a transcriptional activator

ERF proteins can activate or repress transcription of target genes (Fujimoto et al., 2000; Ohta et al., 2001). This study investigated the transcriptional activation potential of SlERF52 using a yeast system, with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) fused to SlERF52 and marker genes expressed under the control of the GAL4 target-binding site. The results showed that the construct with the full-length SlERF52 coding region (GAL4DBD-SlERF521–162) induced expression of the marker genes (Fig. 5), indicating that SlERF52 can activate transcription. To identify which region of SlERF52 is necessary for the activity, three truncated SlERF52 proteins (SlERF521–74, SlERF521–98, and SlERF521–133) were assayed, but no activity was detected in any of the C-terminal truncated proteins (Fig. 5). By contrast, this work did detect activity in a construct with the C-terminal 30 amino acids (GAL4DBD-SlERF52133–162) (Fig. 5). These results indicated that the transcriptional activation activity of SlERF52 requires the C-terminal 30-amino-acid region that contains the CMV-2 motif.

Fig. 5.

SlERF52 functions as a transcriptional activator. (A) Schematic of full-length and truncated SlERF52 proteins examined in this assay; fused products of these proteins with GAL4DBD were expressed in yeast cells. (B) Results of transactivation assays; yeast cells expressing the fusion proteins were inoculated on SD/–Trp (control medium) and SD/–Trp–His–Ade (selection medium). Yeast cells expressing GAL4DBD were used as a negative control.

Discussion

SlERF52 functions as a positive regulator of flower pedicel abscission

These data showed that suppression of SlERF52 reduced the rate of pedicel abscission and repressed induction of the genes for cell-wall hydrolytic enzymes PG and Cel (Cel5, TAPG1, TAPG2, and TAPG4). Abscission of flower pedicels and leaf petioles in tomato requires the activity of these enzymes (Lashbrook et al., 1998; Jiang et al., 2008). Therefore, these results suggest that SlERF52 induces pedicel abscission through upregulation of these enzyme genes. In contrast to the low induction of Cel5, TAPG1, TAPG2, and TAGP4 in the suppressed plants, the expression of Cel1 was not correlated with suppression of SlERF52 or the abscission rate. These results also indicate that the transcript level of Cel1 in the wild type peaked at 1 d after flower removal and then declined, but the transcript levels of Cel5, TAPG1, TAPG2, and TAPG4 continuously increased (Fig. 4). In addition, Cel1 is expressed in a pedicel region distinct from the region where TAPG1 and TAPG4 are expressed (Bar-Dror et al., 2011). These results imply that the transcriptional regulation of Cel1 is independent of the regulation mediated by SlERF52. Therefore, these results indicate that SlERF52 acts as a key positive regulator of flower pedicel abscission, but abscission also involves a SlERF52-independent pathway.

Interestingly, SlERF52 is necessary, but not sufficient, for the upregulation of PG and Cel genes; before the onset of abscission, SlERF52 is also expressed at a similar level to that observed after flower removal, but this expression does not induce PG and Cel gene expression (Fig. 4). Post-transcriptional regulation may explain the transcription-independent activity of SlERF52 (as will be discussed).

SlERF52, a positive regulator of abscission, has an opposite role to that of the Arabidopsis homologues, SHNs, which act as negative regulators of abscission of floral organs such as sepals, stamens, and petals (Shi et al., 2011b ). Simultaneous suppression of all SHN genes induces earlier abscission of floral organs, possibly due to decreased cutin deposition and altered cell-wall composition of structural proteins and pectin (Shi et al., 2011b ). SlERF52 and SHNs belong to the group Va ERF family, but belong to different subgroups based on their CMV-1 motif structures: SlERF52 belongs to the subgroup with an incomplete CMV-1, and the SHNs belong to the subgroup with normal CMV-1 structure (Fig. 2B). The biological function of CMV-1 has not been identified, but the structural difference in CMV-1 between SlERF52 and SHNs may be a possible cause of their functional diversity. Also, the latter half of the CMV-1 motif, which is lost in the incomplete-type Va ERFs, contains an important active site, as demonstrated in a study of mutants of NUD, a barley orthologue of WIN1/SHN1 (Fig. 2B; Taketa et al., 2008). Elucidation of the function of the CMV-1 motif will provide insights into the functional diversity between the subgroups within the Va ERFs, including SlERF52 and SHNs.

Several group Va ERF proteins, including WIN1/SHN1, SHN2, SHN3, and EFD, act as transcriptional activators (Vernie et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2011b ). However, the domain for transcriptional activation was not identified. The current study demonstrated that the C-terminus of SlERF52, which contains the CMV-2 motif, acts as an activation domain. As shown in Fig. 2B, the CMV-2 motif is highly conserved in WIN1/SHN1, SHN2, SHN3, and EFD, suggesting that the conserved motif functions as a transcription activation domain in these proteins.

SlERF52 is involved in the expression of TF genes for shoot apical meristem and axillary meristem function in flower pedicel AZs

LeWUS, GOB, Ls, and Bl, key TF genes for meristem-associated functions, are expressed specifically in flower pedicel AZs, suggesting that these four TFs may have an additional function in control of organ abscission through regulation of meristem-like activity in the cells within the AZ (Nakano et al., 2012, 2013). The current study found that LeWUS, GOB, and Ls were expressed at significantly lower levels in the SlERF52-suppressed plants, implying that SlERF52 may be involved in the regulation of these TF genes. Expression of SlERF52, LeWUS, GOB, and Ls is reduced in pedicels of MC-suppressed plants, SlMBP21-suppressed plants, and j mutants (Nakano et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2014; Fig. 1A), indicating that SlERF52 may mediate the effect of MC, J, and SlMBP21 on these meristem-associated regulators. Two SlERF52 homologues that belong to the incomplete CMV-1 type subgroup regulate plant development through modulation of meristem activity: medicago EFD controls formation of root nodule meristems (Vernie et al., 2008) and poplar PtaERF003 controls formation and growth of adventitious and lateral root meristems (Trupiano et al., 2013). Therefore, the control of meristem-associated regulation may be a conserved biological function for the group Va ERFs with incomplete CMV-1 motifs. PtaERF003 functions in an auxin-regulated pathway that regulates root meristems (Trupiano et al., 2013). Similar to root meristem regulation, expression of the shoot meristem-associated TF genes in the AZs may be regulated by a signalling pathway that requires auxin supplied from the flower before the onset of abscission, and SlERF52 may function in the auxin signalling pathway in the AZs.

The expression analyses revealed that SlERF52 activates the expression of LeWUS, GOB, and Ls in the AZ cells, but the expression of these three TF genes was suppressed after stimulation of abscission, even though SlERF52 expression remained constant (Fig. 4). By contrast, the cell-wall hydrolytic enzyme genes were suppressed before the stimulation of abscission, even though SlERF52 expression remained constant, a reverse pattern to that of the three TF genes. This partial dependence on SlERF52 is discussed in the next section.

Of the four TF genes for meristem-associated functions, Bl exhibits significant upregulation after flower removal, an expression pattern distinct from LeWUS, GOB, and Ls (Fig. 4). Thus, Nakano et al. (2013) hypothesized that an independent pathway controls Bl expression, although MC and J are involved in the expression of all four TF genes. In the current study, the suppression of SlERF52 did not significantly affect Bl expression, indicating that a SlERF52-independent pathway regulates Bl. Also, the intense induction of Bl after flower removal suggests that Bl may be involved in pedicel abscission (Nakano et al., 2013). The induction of Bl in the SlERF52-suppressed plants may help explain the partial progression of abscission in the suppressed lines.

Functional switching of SlERF52 before and after the onset of abscission

SlERF52 functions in the regulation of pedicel abscission and regulates transcription of distinct sets of genes before and after the onset of abscission. In the pre-abscission stage, the expression of LeWUS, GOB, and Ls requires SlERF52, either directly or indirectly. In response to an abscission-inducing stimulus, the expression of Cel5, TAPG1, TAPG2, and TAPG4 was also regulated by SlERF52, directly or indirectly. However, after the onset of abscission, the induction of LeWUS, GOB, and Ls ceases. To explain how SlERF52 is involved in the regulation of distinct sets of genes before and after the onset of abscission, it is postulates that coregulators specify the function of SlERF52 in the different states. In this hypothesis, SlERF52 recruits state-specific TFs and each state-specific TF complex activates expression of a distinct set of target genes. Several ERFs are predicted to require cofactors to bind target genes (Chakravarthy et al., 2003; Kannangara et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2013). As another possibility, repressor proteins or chromatin remodelling at SlERF52-binding sites may restrict the transactivation activity of SlERF52 in a stage-specific manner.

This work used knockdown experiments to examine SlERF52 function. A recent study using overexpression of SlMBP21 provided substantial insights on SlMBP21 gene function, adding to the results of the knockdown assay (Liu et al., 2014). However, unlike the study of SlMBP21, overexpression of SlERF52 may not be effective to clarify SlERF52 function because the activity of SlERF52 in AZs is likely determined by other factors associated with SlERF52, not by the expression level of SlERF52.

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrated that SlERF52 regulates pedicel AZ-specific transcription at both pre-abscission and abscission stages and that the regulation during the latter stage includes some of the genes required for abscission. The functional switching between before and after the onset of abscission, by a still-unknown mechanism, raises the possibility that SlERF52 serves as a hub TF that regulates the phase transition between the two stages. The identification of the switching mechanism will further improve the understanding of abscission.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Supplementary Table S1. Sequences of the oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

Supplementary Table S2. Accession numbers of ERFs used for construction of the phylogenetic tree.

Supplementary Fig. S1. Expression analysis of SlERF52-RNAi transgenic plants.

Supplementary Fig. S2. Expression of SlERF52 and meristem-associated TF genes in shoot apex and leaf axilla.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the science and technology research promotion programme for agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and food industry (to Y.I.). The authors thank Ms Akemi Koma for her technical assistance.

References

- Aharoni A, Dixit S, Jetter R, Thoenes E, van Arkel G, Pereira A. 2004. The SHINE clade of AP2 domain transcription factors activates wax biosynthesis, alters cuticle properties, and confers drought tolerance when overexpressed in Arabidopsis . The Plant Cell 16, 2463–2480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MD, Yamasaki K, Ohme-Takagi M, Tateno M, Suzuki M. 1998. A novel mode of DNA recognition by a beta-sheet revealed by the solution structure of the GCC-box binding domain in complex with DNA. EMBO Journal 17, 5484–5496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banno H, Ikeda Y, Niu QW, Chua NH. 2001. Overexpression of Arabidopsis ESR1 induces initiation of shoot regeneration. The Plant Cell 13, 2609–2618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Dror T, Dermastia M, Kladnik A, et al. 2011. Programmed cell death occurs asymmetrically during abscission in tomato. The Plant Cell 23, 4146–4163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal-Lobo M, Molina A, Solano R. 2002. Constitutive expression of ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1 in Arabidopsis confers resistance to several necrotrophic fungi. The Plant Journal 29, 23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broun P, Poindexter P, Osborne E, Jiang CZ, Riechmann JL. 2004. WIN1, a transcriptional activator of epidermal wax accumulation in Arabidopsis . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 101, 4706–4711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai SQ, Lashbrook CC. 2008. Stamen abscission zone transcriptome profiling reveals new candidates for abscission control: enhanced retention of floral organs in transgenic plants overexpressing Arabidopsis ZINC FINGER PROTEIN2. Plant Physiology 146, 1305–1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarthy S, Tuori RP, D’Ascenzo MD, Fobert PR, Despres C, Martin GB. 2003. The tomato transcription factor Pti4 regulates defense-related gene expression via GCC box and non-GCC box cis elements. The Plant Cell 15, 3033–3050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MK, Hsu WH, Lee PF, Thiruvengadam M, Chen HI, Yang CH. 2011. The MADS box gene, FOREVER YOUNG FLOWER, acts as a repressor controlling floral organ senescence and abscission in Arabidopsis . The Plant Journal 68, 168–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng MC, Liao PM, Kuo WW, Lin TP. 2013. The Arabidopsis ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 regulates abiotic stress-responsive gene expression by binding to different cis-acting elements in response to different stress signals. Plant Physiology 162, 1566–1582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SC, Jang SH, Chae SJ, Chung KM, Moon YH, An GH, Jang SK. 1999. Analysis of the C-terminal region of Arabidopsis thaliana APETALA1 as a transcription activation domain. Plant Molecular Biology 40, 419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cindy RW, Jeff V. 1994. Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer to plant cells: cointegrated and binary vector systems. In: Gelvin SB, Schilperoort RA, eds, Plant molecular biology manual. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; pp 1–19 [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CM, Nagpal P, Young JC, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ, Reed JW. 2005. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR1 and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2 regulate senescence and floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana . Development 132, 4563–4574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exposito-Rodriguez M, Borges AA, Borges-Perez A, Perez JA. 2008. Selection of internal control genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR studies during tomato development process. BMC Plant Biology 8, 131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez DE, Heck GR, Perry SE, Patterson SE, Bleecker AB, Fang SC. 2000. The embryo MADS domain factor AGL15 acts postembryonically: inhibition of perianth senescence and abscission via constitutive expression. The Plant Cell 12, 183–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto SY, Ohta M, Usui A, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M. 2000. Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factors act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box-mediated gene expression. The Plant Cell 12, 393–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu YQ, Wildermuth MC, Chakravarthy S, Loh YT, Yang C, He X, Han Y, Martin GB. 2002. Tomato transcription factors pti4, pti5, and pti6 activate defense responses when expressed in Arabidopsis . The Plant Cell 14, 817–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao DY, Ohme-Takagi M, Sarai A. 1998. Unique mode of GCC box recognition by the DNA-binding domain of ethylene-responsive element-binding factor (ERF domain) in plant. Journal of Biological Chemistry 273, 26857–26861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase A, Mitsuda N, Koyama T, et al. 2011. The AP2/ERF transcription factor WIND1 controls cell dedifferentiation in Arabidopsis . Current Biology 21, 508–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang CZ, Lu F, Imsabai W, Meir S, Reid MS. 2008. Silencing polygalacturonase expression inhibits tomato petiole abscission. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 973–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannangara R, Branigan C, Liu Y, Penfield T, Rao V, Mouille G, Hofte H, Pauly M, Riechmann JL, Broun P. 2007. The transcription factor WIN1/SHN1 regulates cutin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana . The Plant Cell 19, 1278–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirch T, Simon R, Grunewald M, Werr W. 2003. The DORNROSCHEN/ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION1 gene of Arabidopsis acts in the control of meristem cell fate and lateral organ development. The Plant Cell 15, 694–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Chujo A, Nagato Y, Shimamoto K, Kyozuka J. 2003. FRIZZY PANICLE is required to prevent the formation of axillary meristems and to establish floral meristem identity in rice spikelets. Development 130, 3841–3850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashbrook CC, Giovannoni JJ, Hall BD, Fischer RL, Bennett AB. 1998. Transgenic analysis of tomato endo-beta-1,4-glucanase gene function. Role of cel1 in floral abscission. The Plant Journal 13, 303–310 [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Zhu BZ, Xu WT, Zhu HL, Chen AJ, Xie YH, Shao Y, Luo YB. 2007. LeERF1 positively modulated ethylene triple response on etiolated seedling, plant development and fruit ripening and softening in tomato. Plant Cell Reports 26, 1999–2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Wang D, Qin Z, Zhang D, Yin L, Wu L, Colasanti J, Li A, Mao L. 2014. The SEPALLATA MADS-box protein SLMBP21 forms protein complexes with JOINTLESS and MACROCALYX as a transcription activator for development of the tomato flower abscission zone. The Plant Journal (E-pub ahead of print, 10.1111/tpj.12387). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Kasuga M, Sakuma Y, Abe H, Miura S, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. 1998. Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in drought- and low-temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis . The Plant Cell 10, 1391–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Begum D, Chuang HW, Budiman MA, Szymkowiak EJ, Irish EE, Wing RA. 2000. JOINTLESS is a MADS-box gene controlling tomato flower abscission zone development. Nature 406, 910–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meir S, Philosoph-Hadas S, Sundaresan S, Selvaraj KSV, Burd S, Ophir R, Kochanek B, Reid MS, Jiang CZ, Lers A. 2010. Microarray analysis of the abscission-related transcriptome in the tomato flower abscission zone in response to auxin depletion. Plant Physiology 154, 1929–1956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T, Fujisawa M, Shima Y, Ito Y. 2013. Expression profiling of tomato pre-abscission pedicels provides insights into abscission zone properties including competence to respond to abscission signals. BMC Plant Biology 13, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T, Ito Y. 2013. Molecular mechanisms controlling plant organ abscission. Plant Biotechnology 30, 209–216 [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T, Kimbara J, Fujisawa M, Kitagawa M, Ihashi N, Maeda H, Kasumi T, Ito Y. 2012. MACROCALYX and JOINTLESS interact in the transcriptional regulation of tomato fruit abscission zone development. Plant Physiology 158, 439–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T, Suzuki K, Fujimura T, Shinshi H. 2006. Genome-wide analysis of the ERF gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiology 140, 411–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohme-Takagi M, Shinshi H. 1995. Ethylene-inducible DNA-binding proteins that interact with an ethylene-responsive element. The Plant Cell 7, 173–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta M, Matsui K, Hiratsu K, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M. 2001. Repression domains of class II ERF transcriptional repressors share an essential motif for active repression. The Plant Cell 13, 1959–1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, et al. 2000. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science 290, 2105–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JA, Elliott KA, Gonzalez-Carranza ZH. 2002. Abscission, dehiscence, and other cell separation processes. Annual Review of Plant Biology 53, 131–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher K, Schmitt T, Rossberg M, Schmitz G, Theres K. 1999. The lateral suppressor (Ls) gene of tomato encodes a new member of the VHIID protein family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 96, 290–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma MK, Kumar R, Solanke AU, Sharma R, Tyagi AK, Sharma AK. 2010. Identification, phylogeny, and transcript profiling of ERF family genes during development and abiotic stress treatments in tomato. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 284, 455–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi CL, Stenvik GE, Vie AK, Bones AM, Pautot V, Proveniers M, Aalen RB, Butenko MA. 2011a. Arabidopsis class I KNOTTED-like homeobox proteins act downstream in the IDA-HAE/HSL2 floral abscission signaling pathway. The Plant Cell 23, 2553–2567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi JX, Adato A, Alkan N, et al. 2013. The tomato SlSHINE3 transcription factor regulates fruit cuticle formation and epidermal patterning. New Phytologist 197, 468–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi JX, Malitsky S, De Oliveira S, Branigan C, Franke RB, Schreiber L, Aharoni A. 2011b. SHINE transcription factors act redundantly to pattern the archetypal surface of Arabidopsis flower organs. PLoS Genetics 7, e1001388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji T, Kajikawa M, Hashimoto T. 2010. Clustered transcription factor genes regulate nicotine biosynthesis in tobacco. The Plant Cell 22, 3390–3409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano R, Stepanova A, Chao Q, Ecker JR. 1998. Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes and Development 12, 3703–3714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger EJ, Gilmour SJ, Thomashow MF. 1997. Arabidopsis thaliana CBF1 encodes an AP2 domain-containing transcriptional activator that binds to the C-repeat/DRE, a cis-acting DNA regulatory element that stimulates transcription in response to low temperature and water deficit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 94, 1035–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun HJ, Uchii S, Watanabe S, Ezura H. 2006. A highly efficient transformation protocol for Micro-Tom, a model cultivar for tomato functional genomics. Plant and Cell Physiology 47, 426–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taketa S, Amano S, Tsujino Y, et al. 2008. Barley grain with adhering hulls is controlled by an ERF family transcription factor gene regulating a lipid biosynthesis pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 105, 4062–4067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JE, Whitelaw CA. 2001. Signals in abscission. New Phytologist 151, 323–339 [Google Scholar]

- Trupiano D, Yordanov Y, Regan S, Meilan R, Tschaplinski T, Scippa GS, Busov V. 2013. Identification, characterization of an AP2/ERF transcription factor that promotes adventitious, lateral root formation in Populus . Planta 238, 271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Fits L, Memelink J. 2000. ORCA3, a jasmonate-responsive transcriptional regulator of plant primary and secondary metabolism. Science 289, 295–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernie T, Moreau S, de Billy F, Plet J, Combier JP, Rogers C, Oldroyd G, Frugier F, Niebel A, Gamas P. 2008. EFD is an ERF transcription factor involved in the control of nodule number and differentiation in Medicago truncatula . The Plant Cell 20, 2696–2713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Liu D, Li A, Sun X, Zhang R, Wu L, Liang Y, Mao L. 2013. Transcriptome analysis of tomato flower pedicel tissues reveals abscission zone-specific modulation of key meristem activity genes. PLoS One 8, e55238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei PC, Tan F, Gao XQ, Zhang XQ, Wang GQ, Xu H, Li LJ, Chen J, Wang XC. 2010. Overexpression of AtDOF4.7, an Arabidopsis DOF family transcription factor, induces floral organ abscission deficiency in Arabidopsis . Plant Physiology 153, 1031–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Xu X, Fukao T, Canlas P, Maghirang-Rodriguez R, Heuer S, Ismail AM, Bailey-Serres J, Ronald PC, Mackill DJ. 2006. Sub1A is an ethylene-response-factor-like gene that confers submergence tolerance to rice. Nature 442, 705–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SO, Wang SC, Liu XG, Yu Y, Yue L, Wang XP, Hao DY. 2009. Four divergent Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element-binding factor domains bind to a target DNA motif with a universal CG step core recognition and different flanking bases preference. FEBS Journal 276, 7177–7186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TJ, Lee S, Chang SB, Yu Y, Jong H, Wing RA. 2005. In-depth sequence analysis of the tomato chromosome 12 centromeric region: identification of a large CAA block and characterization of pericentromere retrotranposons. Chromosoma 114, 103–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.