Abstract

Trichome initiation and patterning are controlled by the TTG1–bHLH–MYB regulatory complex. Several MYB transcription factors have been determined to function in trichome development via incorporation into this complex. This study examined the role of MYB82, an R2R3-MYB transcription factor, in Arabidopsis trichome development. MYB82 was revealed to be a nuclear-localized transcription activator. Suppression of MYB82 function by fusion with a dominant repression domain (SRDX) resulted in glabrous leaves, as did overexpression of N-terminal-truncated MYB82. Overexpression of MYB82 genomic sequence, but not its cDNA sequence, led to reduced trichome numbers. Further investigation indicated that at least one of the two introns in MYB82 is essential to the protein’s trichome developmental function. An MYB-binding box was identified in the third exon of MYB82, which was inferred to be crucial for MYB82 function because the mutation of this box interfered with the ability of MYB82 to rescue the gl1 mutant. Protein interaction analysis revealed that MYB82 physically interacts with GLABRA3 (GL3). In addition, MYB82 and GL1 can form homodimers and heterodimers at R2R3-MYB domains, which may explain why their overexpression reduces trichome numbers. These results demonstrate the functional diversification of MYB82 and GL1 in trichome development.

Key words: MYB82, GL1, GL3, trichome, Arabidopsis.

Introduction

Trichomes are single-celled epidermal hairs that help protect plants against herbivores, transpirational water loss, and UV irradiation (Marricio and Rausher, 1997; Serna and Martin, 2006). In Arabidopsis, trichomes exist on most aerial plant parts, including rosette leaves, stems, cauline leaves, and sepals, but not on hypocotyls and cotyledons. Trichome morphology and density vary among different organs. Trichomes on rosette leaves contain three to four branches, whereas cauline and stem trichomes are less branched or unbranched, respectively. Trichome density on the abaxial side of leaves increases with plant transition from vegetative to reproductive growth (Telfer et al., 1997).

Trichome formation is controlled by programmed cell determination. The initiation and formation of trichomes has been extensively studied. The trichome developmental process is strictly controlled by transcription factors, which recognize specific DNA motifs in gene regulatory regions to activate or repress transcription, possibly through interaction with other proteins. Trichome initiation is regulated by a network under the control of a WD40–bHLH–MYB complex. In Arabidopsis, TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 (TTG1), a WD40 repeat protein, regulates trichome differentiation. Loss of function of TTG1 can also result in a lack of trichomes (Walker et al., 1999). GL3 and EGL3 are two functionally redundant bHLH transcription factors, both of which regulate trichome initiation and act as a bridge to mediate the interaction between MYB and TTG1 (Payne et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2003). The R2R3-MYB transcription factor GL1 is necessary for trichome initiation, and its mutation causes glabrous leaves (Oppenheimer et al., 1991). MYB23 is functionally equivalent to GL1 during trichome initiation, and they redundantly regulate trichome initiation at leaf edges (Kirik et al., 2005). In contrast to R2R3-MYB proteins, single-repeat R3-MYB proteins act as negative regulators of trichome development. These R3-MYB proteins consist of seven members: CAPRICE (CPC), TRIPTYCHON (TRY), ENHANCER OF TRY AND CPC 1 (ETC1), ETC2, ETC3, TRICHOMELESS1 (TCL1), and TCL2. CPC, TRY, ETC1, ETC2, and ETC3 function redundantly in trichome development (Esch et al., 2004; Kirik et al., 2004a,b; Schellmann et al., 2007; Wester et al., 2009). TCL1 plays an important role in trichome formation on stems and pedicels (Wang et al., 2007), and TCL2 functions redundantly with TCL1 in controlling trichome formation on inflorescences (Gan et al., 2011). It has been suggested that single-repeat R3-MYB proteins negatively regulate trichome development by competing with GL1 for binding to GL3/EGL3, resulting in disruption of (R2R3-MYB)–bHLH–TTG1 complexes (Payne et al., 2000; Bernhardt et al., 2003; Esch et al., 2003; Ishida et al., 2008).

The WD40–bHLH–MYB complex regulates the expression of downstream genes to control trichome development. GLABRA2 (GL2), a homeodomain (HD-Zip) transcription factor, is required for trichome morphogenesis. The gl2 mutant produces abnormal trichomes (i.e. most of the trichomes do not expand, and possess only a single branch; Rerie et al., 1994; Masucci et al., 1996; Fyvie et al., 2000; Ohashi et al., 2002). TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2 (TTG2), a WRKY transcription factor, shares functions with GLABRA2 in controlling trichome outgrowth. Mutation in TTG2 causes unbranched trichomes (Johnson et al., 2002). GL2 is directly regulated by GL1, GL3, and EGL3 (Morohashi et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2008), and TTG2 is a direct target of GL1 (Ishida et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2008).

This study focused on the function of MYB82 in trichome development and demonstrated that MYB82 functions in the plant cell nucleus as a positive regulator. Although MYB82 loss of function did not disrupt trichome development, MYB82 overexpression led to abnormal trichome development. On the other hand, overexpression of MYB82-SRDX (fused with a dominant repression domain) or an N-terminal R2R3-MYB domain caused glabrous leaves. MYB82 driven by the GL1 promoter was able to rescue the glabrous phenotypes of the gl1 mutant, suggesting that the MYB82 protein is functionally equivalent to the GL1 protein. The MYB82 gene contains two introns, at least one of which was found to be crucial for MYB82 regulation of trichome development. The third exon of MYB82 contains a perfect MYB-binding box that was demonstrated to be also necessary for MYB82 function. Similar to GL1, MYB82 was able to interact with GL3, suggesting that MYB82 is incorporated into the WD40–bHLH–MYB complex to participate in the regulation of trichome development. In addition, this study revealed that MYB82 proteins can form homodimers or heterodimers with GL1 proteins.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Arabidopsis ecotype Col-0 and its gl1 mutant were used for experiments. Plants were grown at 23 °C under a 16/8h light/dark cycle or a 8/16 light/dark cycle.

Subcellular localization

Full-length cDNA of MYB82 was fused with that of the eGFP protein in a frame downstream of the 35S promoter in a pOCA30a binary vector. The resulting 35S:MYB82-eGFP plasmid was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105. The transformed Agrobacterium was incubated, harvested, and resuspended in infiltration buffer (0.2mM acetosyringone, 10mM MgCl2, and 10mM MES, pH 5.6) and then infiltrated into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. After infiltration, plants were incubated at 24 °C for 48h before observation. DAPI staining was used for visualization of cell nuclear DNA. GFP and DAPI fluorescence were observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA (1 μg), extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), was used for oligo(dT)18-primed cDNA synthesis according to the reverse transcription protocol (Fermentas). The resulting cDNA was subjected to real-time quantitative RT-PCR using a SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (Takara) on a Roche LightCycler 480 real-time PCR machine. For each reported result, at least three independent biological samples were subjected to a minimum of three technical replicates. The results were normalized using the internal control ACTIN2. The primers for quantitative RT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S2 (available at JXB online).

Plasmid construction

For the 35S:MYB82-eGFP plasmid, MYB82 cDNA was fused in-frame to the 5′-terminal of eGFP driven by the CaMV 35S promoter in a pOCA30a binary vector. For the 35S:MYB82(/GL1)-SRDX plasmid, the MYB82/GL1 genomic sequence was fused with the minimal repression domain (DLELRL). GL1 regulatory sequences used in these experiments were described previously (Lee and Schiefelbein, 2001) and included a 1.4-kb 5′-fragment and a 1.8-kb 3′-fragment. A 5×GAL4+35S minimal promoter sequence was synthesized and inserted into an upstream GUS gene in a binary vector. GAL4 DNA-binding domain (BD) and GAL4 activation domain (AD; AD domain containing nuclear-localized signal from SV40) sequences were amplified from pGBKT7 and pGADT7 plasmids, respectively. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Plasmid construction details are available upon request.

GUS reporter analysis

The putative promoters of MYB82 were amplified from genomic DNA using primers Pro-MYB82-F and Pro-MYB82-R (Supplementary Table S2). The fused Pro myb82 -GUS was cloned into the pOCA28 vector. Transgenic plants were subjected to GUS staining as described by He et al. (2014).

Yeast two-hybrid assay

Fusions with the GAL4 activation domain and the GAL4 DNA-binding domain were performed in the pGBKT7 and pGADT7 plasmids. Full lengths or fragments of GL3, MYB82, and GL1 were individually cloned into pGBKT7 or pGADT7 plasmids. Growth was determined as described in the Yeast Two-Hybrid System user manual (Clontech).

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay

Full-length coding sequences of MYB82 and GL3 were cloned into binary N-terminal fragment of yellow fluorescent protein (nYFP)and C-terminal fragment of yellow fluorescent protein (cYFP) vectors, respectively. Agrobacterium strains transformed with indicated nYFP or cYFP vectors were incubated, harvested, and resuspended in infiltration buffer (0.2mM acetosyringone, 10mM MgCl2, and 10mM MES, pH 5.6) to identical concentrations (A 600=0.5). Equal volumes of an Agrobacterium culture containing nYFP (A 600=0.5) and cYFP (A 600=0.5) were mixed before infiltration into N. benthamiana leaves. After infiltration, plants were incubated at 24 °C for 48h before observation.

Results

MYB82 is a nuclear-localized transcription activation factor

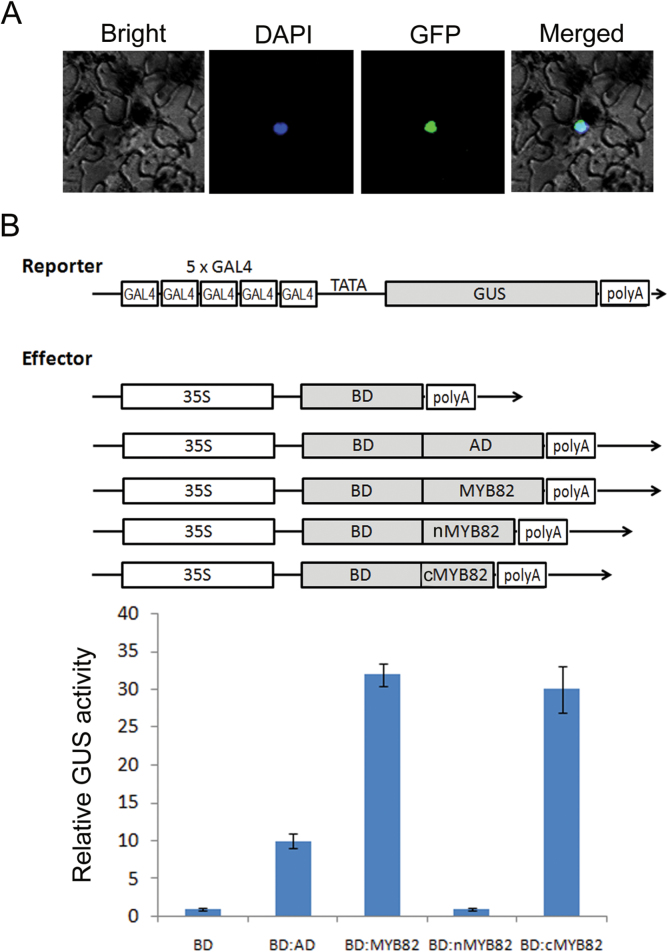

To identify the subcellular localization of MYB82, its coding region was fused with an ENHANCED GREEN FLUORESCENT PROTEIN (eGFP) reporter gene under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter. Tobacco epidermal cells transformed to transiently express MYB82-eGFP showed considerable fluorescent signal in cell nuclei, with no signal observed in other compartments (Fig. 1A). This result suggested that MYB82 is a nuclear-localized transcription factor.

Fig. 1.

MYB82 is a nuclear-localized transcription activation factor. (A) Confocal images showing the subcellular distribution of eGFP-tagged MYB82 fusion proteins in transiently transformed tobacco cells; Nicotiana benthamiana plants were infiltrated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells harbouring 35S:MYB82-eGFP plasmids. (B) Transcription activation of MYB82 tethered to DNA through Gal4 BD (DB:MYB82); reporter and effector were transiently coexpressed in tobacco cells.

MYB transcription factors function as transcription activators or repressors (Dubos et al., 2010). To clarify whether MYB82 is a transcription activator or a transcription repressor, this work performed transient transcription assays in tobacco leaves. The reporter plasmid contained five tandem copies of the GAL4-binding site upstream of the GUS reporter gene (Fig. 1B). Full-length MYB82 was fused to the GAL4 BD downstream of the 35S promoter as an effector plasmid (Fig. 1B). The GAL4 AD was fused to BD to generate GAL4-BD:AD as a positive effector. Compared with GAL4-BD, GAL4-BD:AD significantly stimulated expression of GUS. When GAL4-BD:MYB82 was coexpressed with the reporter, GUS activities were higher than those observed from GAL4-BD:AD coexpression with the reporter (Fig. 1B). These data demonstrated that MYB82 was able to activate transcription via its intrinsic activation domain.

To further confirm which domain functions as a transcription activation domain, the N-terminal R2R3-MYB domain (nMYB82) and C-terminal domain (cMYB82) were separately fused to GAL4-BD. Coexpression results indicated that the C-terminal domain was responsible for the transcription activation function. Taken together, these data suggested that MYB82 is a nuclear-localized transcription activation factor.

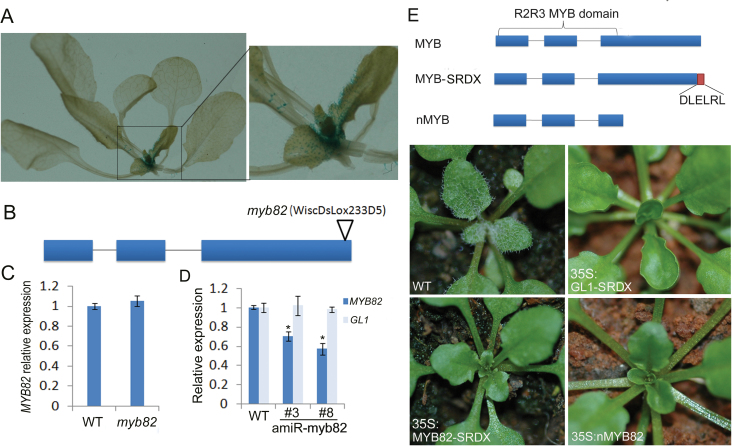

Function repression of MYB82 resulted in glabrous leaves

Although the functions of MYB82 are unclear, its protein sequence is highly similar to GL1 (Supplementary Fig. S1), an R2R3-MYB subgroup-15 member (Dubos et al., 2010) and a key regulator of trichome initiation (Oppenheimer et al., 1991). This work speculated that MYB82 might be involved in regulation of trichome development. To confirm this hypothesis, first the expression pattern of MYB82 was determined. The upstream sequence of MYB82 was used to drive the GUS reporter gene (Pro MYB82 :GUS), which allowed transcription regulation of MYB82 to be monitored. GUS staining suggested that Pro MYB82 :GUS was mainly expressed in the trichomes of new leaves (Fig. 2A), which implied that MYB82 might function in the initiation of trichomes. This work then obtained a homozygous T-DNA insertion line for MYB82, which was generated by the deletion of seven C-terminal amino acids (Fig. 2B). Expression analysis revealed that the abundance of truncated transcripts in the mutant was similar to the level of full-length transcripts present in the wild type (Fig. 2C). Moreover, this mutant was not phenotypically different from wild-type plants. These results suggested that the MYB82 3′-terminal deletion may not affect this protein’s function. Therefore, this work used an artificial miRNA approach (Liang et al., 2012) to suppress MYB82 expression. An amiR-myb82 sequence was designed using WMD3 (http://wmd3.weigelworld.org), with an Ath-miR395a backbone used to drive its expression (Liang et al., 2012). The amiR-myb82 precursor was inserted into the downstream of the 35S promoter in a binary vector. Twenty transgenic plants were further analysed for MYB82 transcript levels (Supplementary Fig. S1). As expected, MYB82 mRNA abundance was decreased in amiR-myb82 transgenic plants, with GL1 mRNA unchanged (Fig. 2D); however, no obvious phenotypic difference was observed between amiR-myb82 and wild-type plants, implying that MYB82 may function redundantly with its closely homologous genes.

Fig. 2.

Function repression of MYB82 caused a reduction in leaf trichome number. (A) GUS staining of Pro myb82 :GUS reporter line. (B) Location of T-DNA in the MYB82 gene; bars and lines indicate exons and introns, respectively; the triangle indicates the location of the T-DNA. (C and D) Transcript abundance of MYB82 in the myb82 mutant (C) and amiR-myb82 transformants (D); transcript abundance of GL1 is shown as a negative control; #3 and #8 correspond to two independent amiR-myb82 transformants. (E) Phenotypes of transformants with altered MYB proteins; red bar indicates the SRDX domain (DLELRL), MYB-SRDX indicates the MYB protein fused with an SRDX domain, and nMYB indicates the MYB protein containing only the R2R3 MYB domain.

Based on the fact that fusion of a dominant repression domain to a transcriptional activator can convert the latter into a strong repressor by repressing target gene expression (Hiratsu et al., 2003), this work employed a dominant repression approach to investigate MYB82 function. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants (35S:MYB82-SRDX) expressing MYB82 fused with the dominant EAR repression domain (Hiratsu et al., 2004) were generated. The resulting 35S:MYB82-SRDX transgenic plants produced nearly glabrous leaves with a few trichomes in leaf margins (Fig. 2E), reminiscent of the phenotypes exhibited by the trichome defective mutant gl1. As a positive control, 35S:GL1-SRDX transgenic plants were also generated; as expected, 35S:GL1-SRDX transgenic plants produced completely glabrous leaves.

The MYB82 protein consists of one N-terminal R2R3-MYB DNA-binding domain and one C-terminal activation domain. This work hypothesized that overexpression of the N-terminal DNA-binding domain would confer a dominant negative effect by preventing endogenous MYB82 or homologous proteins from associating with their target DNA motif. When nMYB82 with a deletion of the C-terminal domain was constitutively expressed (35S:nMYB82), trichome initiation completely failed, even in leaf margins.

GL2, a downstream target gene of WD40–bHLH–MYB complex, is expressed in the trichome and required for trichome development. This work investigated whether these transgenic plants with less trichomes have low GL2 expression levels. As expected, the trichome number agreed well with GL2 transcript abundance in these transgenic plants (Supplementary Fig. S2). Taken together, MYB82 positively regulates trichome development.

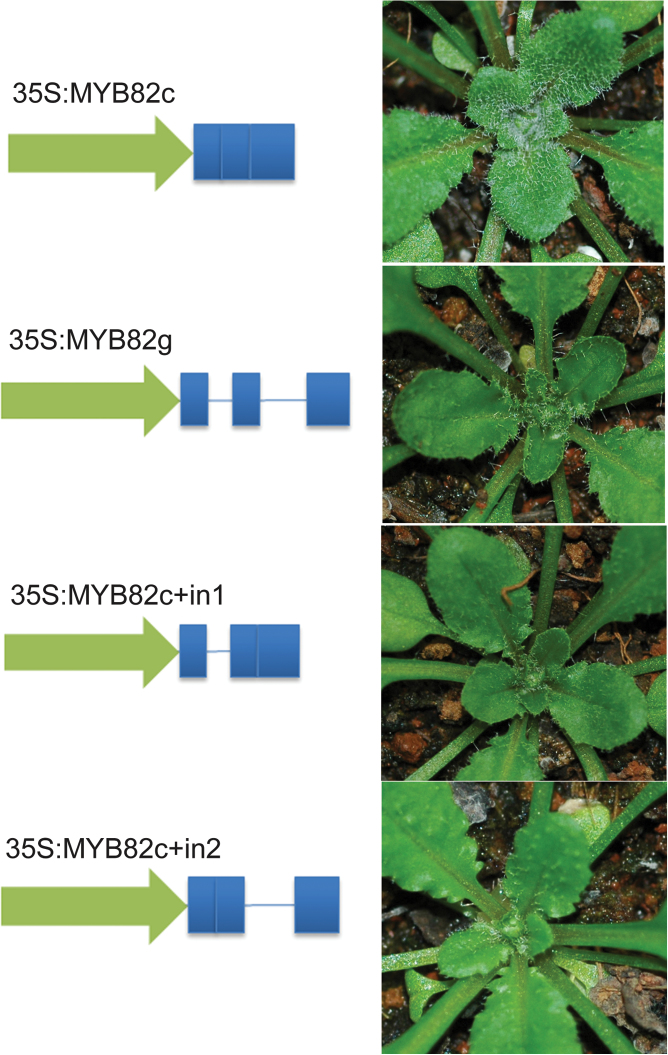

MYB82 introns affected its function

Although GL1 positively regulates trichome initiation, GL1 overexpression reduces trichome number (Larkin et al., 1994). To investigate the effects of constitutive and ectopic expression of MYB82, MYB82 cDNA was inserted downstream of the 35S promoter in a binary vector. The 35S:MYB82c construct was transformed into wild-type Arabidopsis plants. Unexpectedly, no visible trichome-defective phenotype (Fig. 3) was observed in any of the 37 35S:MYB82c transformants although most of them contained high levels of MYB82 transcripts (Supplementary Table S1). It has been suggested that the second introns of GL1 and GaMYB2 contain an MYB-binding box required for gene function (Wang et al., 2004); however, the current work was unable to find a similar MYB-binding box in the two introns of MYB82. Considering the possibility that unknown cis-elements are present in the introns, transgenic plants constitutively expressing the MYB82 genomic sequence (35S:MYB82g) were constructed (Fig. 3). Among the 30 35S:MYB82g transformants, 70% surprisingly showed reduced trichome numbers, with the remaining 30% exhibiting no difference compared with wild-type plants. This result implied that the introns of MYB82 play important roles in gene function. To determine which intron was involved in gene functional regulation, two constructs (35S:MYB82c+in1 and 35S:MYB82c+in2), each containing MYB82c and one of the two introns, were produced (Fig. 3). The phenotypes of 35S:MYB82c+in1 and 35S:MYB82c+in2 transgenic plants were similar, both displaying reduced trichome numbers. It thus appears that at least one intron is involved in the function of MYB82 in trichome development.

Fig. 3.

Effect of MYB82 introns on trichome development. Schematic presentations of constructs are depicted on the left; arrows indicate the 35S promoter; bars and lines indicate MYB82 exons and introns, respectively. Wild-type plants were used for transformation. Representative transformants are shown.

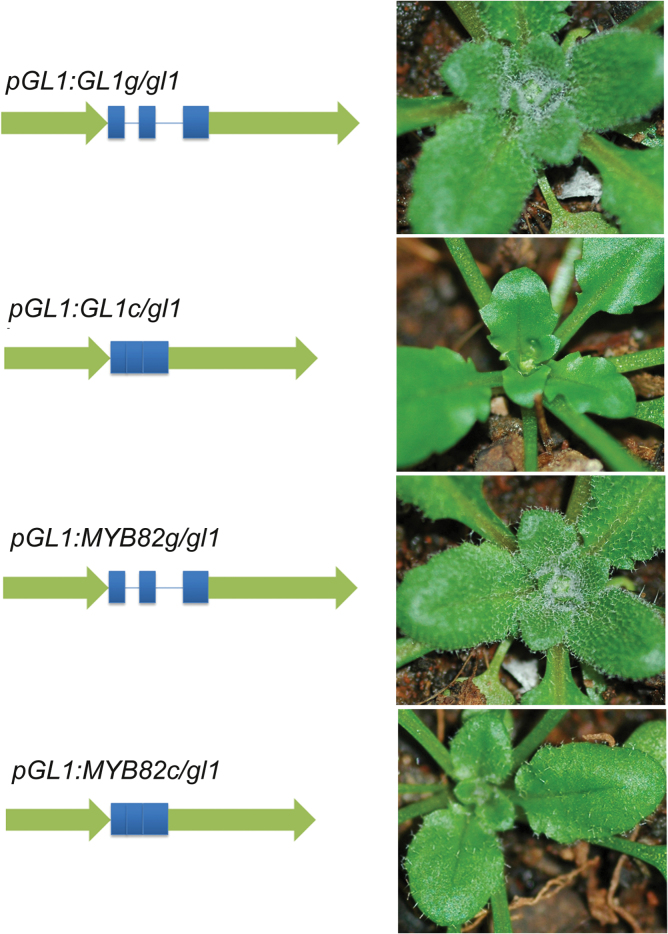

Both pGL1:MYB82g and pGL1:MYB82c could rescue gl1 mutants

Analysis of MYB82 loss- and gain-of-function suggested that MYB82 could mediate Arabidopsis trichome development. Given that MYB82 displayed a function similar to GL1, this work investigated whether the MBY82 protein was able to complement the trichome defect of the gl1 mutant. Because 1.4-kb upstream and 1.8-kb downstream regions of the GL1 gene are necessary for its appropriate expression (Lee and Schiefelbein, 2001), these two regions were used for the GL1 promoter (Fig. 4). As a positive control, the GL1 promoter was used to drive GL1c or GL1g in the gl1 mutant (Fig. 4). In accordance with a previous report (Wang et al., 2004), pGL1:GLg, but not pGL:GLc, was able to rescue the gl1 mutant. pGL1:MYB82g and pGL1:MYB82c were constructed in a similar fashion. When these two constructs were separately introduced into the gl1 mutant, pGL1:MYB82g completely complemented the mutant, with leaf trichome densities comparable to the wild type, whereas pGL1:MYB82c partially complemented the gl1 mutant, with trichome densities lower than the wild type but higher than the gl1 mutant (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Rescue of the gl1 mutant by MYB82. Schematic presentations of constructs are depicted on the left; arrows indicate the GL1 promoter; bars and lines indicate MYB82 exons and introns, respectively. gl1 mutant plants were used for transformation. Representative transformants are shown.

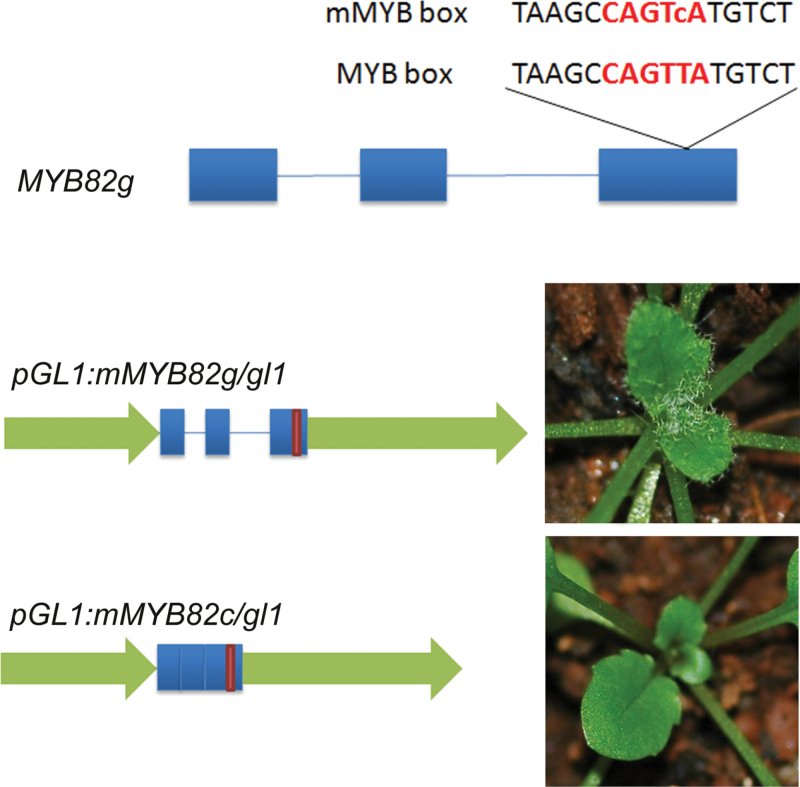

The MYB-binding box in the third exon of MYB82 was crucial for gene function

Although pGL1:MYB82c promoted trichome initiation in the gl1 mutant, pGL1:GL1c did not (Wang et al., 2004). These results were confusing, because 35S:MYB82c had no effect on trichome phenotypes. The first intron of the GL1 gene contains an MYB-binding box required for GL1 expression, which explains why pGL1:GL1c could not rescue the gl1 mutant (Wang et al., 2004). However, no MYB-binding boxes are present in MYB82 introns. Speculating that an unidentified cis-element exists in exon sequences of MYB82, this work searched the complete MYB82 genomic sequence and found a perfect MYB-binding box in the third exon (Fig. 5). In contrast, no MYB-binding boxes exist in GL1 gene exons. This box is thus likely responsible for MYB82 gene function. To confirm this hypothesis, this work changed the MYB-binding box sequence without altering the amino acid sequence to generate mMBY82g and mMYB82c (Fig. 5) and then used pGL1:mMYB82g and pGL1:mMYB82c in a complementation assay of the gl1 mutant. As shown in Fig. 5, pGL1:mMYB82g partially complemented gl1, whereas pGL1:mMYB82c had no effect on gl1 trichome initiation. These results suggested that the MYB-binding box in the third exon of MYB82 is required for MYB82 function in trichome initiation.

Fig. 5.

Effect of the MYB-binding box of MYB82 on trichome development. Schematic presentations of constructs are depicted on the left; red letters indicate the wild-type and mutated MYB-binding box; arrows indicate the GL1 promoter; bars and lines indicate MYB82 exons and introns, respectively; red bar indicates a mutated MYB-binding box.

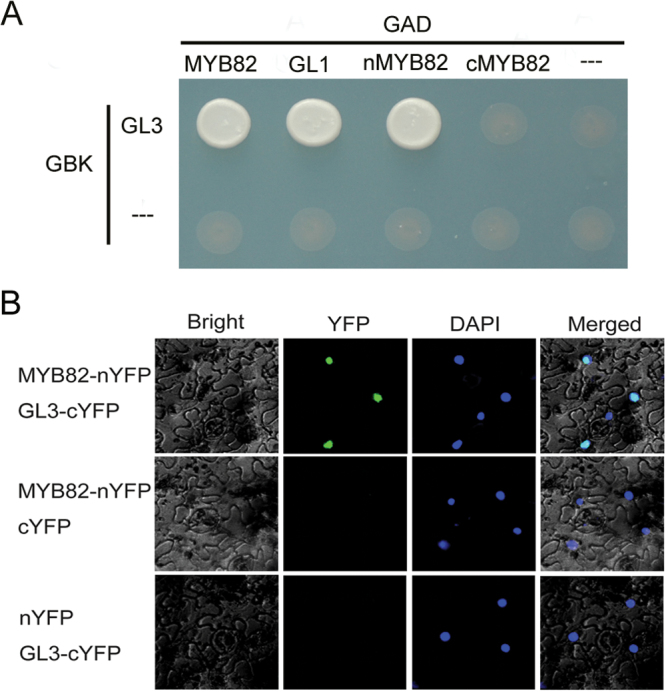

MYB82 was incorporated into the TTG1–bHLH–MYB complex

The conserved signature motif ([DE]Lx2[RK]x3Lx6Lx3R) of MYB proteins is crucial for their interaction with the bHLH protein GL3 that functions in trichome initiation and anthocyanin synthesis (Zimmermann et al., 2004; Dubos et al., 2010). This motif also exists in the MYB82 protein (Supplementary Fig. S3). To verify whether MYB82 interacts with GL3, the MYB82 full-length coding region was fused to the BD domain of pGBK-T7, and GL3 was fused to the AD domain of pGAD-T7. Yeast two-hybrid assays suggested that MYB82 interacted with GL3 (Fig. 6A). To determine which region of the MYB82 protein is responsible for this interaction, the N-terminal region containing the MYB domain and the C-terminal region were separately fused with the BD domain. The N-terminal region was found to be sufficient for MYB82 interaction with GL3 (Fig. 6A). To confirm whether this interaction also occurred in plant cells, bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays were employed (Fig. 6B). nYFP was ligated to MYB82 and cYFP was ligated to GL3. When MYB82-nYFP was transiently coexpressed with GL3-cYFP, strong YFP fluorescence was visible in epidermal cell nuclei of N. benthamiana leaves. No YFP fluorescence was detected in negative controls (i.e. MYB82-nYFP coexpressed with cYFP or nYFP coexpressed with GL3-cYFP; Fig. 6B). These results suggested that MYB82 physically interacts with GL3 in plant cell nuclei.

Fig. 6.

Interactor of the MYB82 protein. (A) Interaction of MYB82 with GL3 in yeast; interaction was indicated by the ability of cells to grow on synthetic dropout medium lacking Leu/Trp/His/Ade and containing 5mM 3AT; full-length MYB (MYB82 and GL1), N-terminal truncated MYB (nMYB), and C-terminal truncated MYB (cMYB) were cloned into pGBKT7; full-length GL3 was cloned into pGADT7. (B) Interaction of MYB82 with GL3 in plant cells; fluorescence was observed in nuclear compartments of Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermal cells, resulting from complementation of the N-terminal portion of YFP fused to MYB82 (MYB82-nYFP) with the C-terminal portion of YFP fused to GL3 (GL3-cYFP).

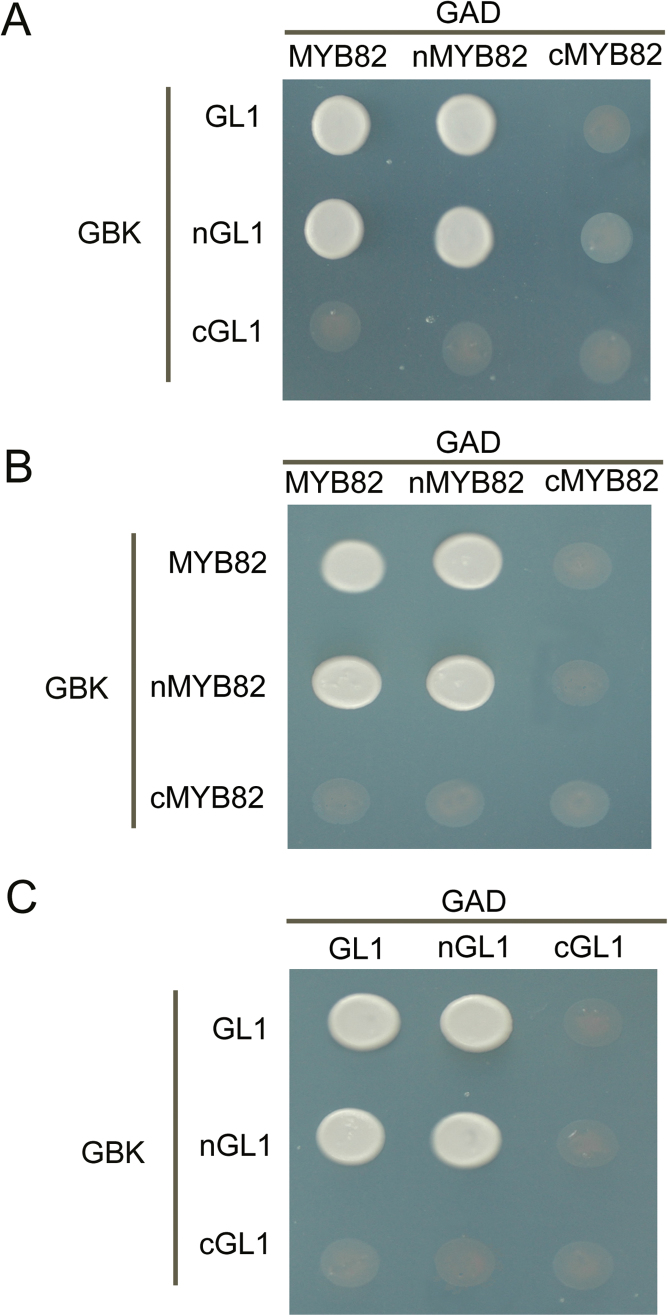

MYB82 and GL1 formed homodimers and heterodimers

Many transcription factors, including bHLH and bZIP transcription factors, function as homo- or heterodimers (Murre et al., 1989; Ferre-D’Amare et al., 1994; Vinson et al., 2002). The Phosphate Starvation Response 1 (PHR1) protein containing a single MYB repeat has been shown to function as a dimer (Rubio et al., 2001). Two closely related R2R3-MYB proteins, MYB21 and MYB24, were recently confirmed to form homo- and heterodimers (Song et al., 2011). Given their similar protein sequences and functions, dimeric interaction likely exists between MYB82 and GL1. To verify this possibility, this work performed a yeast two-hybrid assay. As expected, both MYB82 and GL1 were able to form homodimers and heterodimers (Fig. 7). This work also determined the domain responsible for the interaction, finding that the N-terminal MYB domain is necessary and sufficient for dimer formation (Fig. 7A and B).

Fig. 7.

MYB82 and GL1 form homodimers and heterodimers. (A) MYB82 and GL1 form a heterodimer. (B) MYB82 displays homomeric interaction. (C) GL1 displays homomeric interaction. nMYB82 (nGL1) indicates an N-terminal truncated protein and cMYB82 (cGL1) indicates a C-terminal truncated protein. Interaction was indicated by the ability of cells to grow on synthetic dropout medium lacking Leu/Trp/His/Ade and containing 5mM 3AT.

Discussion

Most R2R3-MYB proteins have been characterized using genetic approaches and have been found to be involved in the control of plant-specific processes such as primary and secondary metabolism, cell fate and identity, developmental processes, and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses (Dubos et al., 2010). A particularly interesting entity is the WD40–bHLH–MYB transcription complex, which has specific functions determined by different MYB proteins. For instance, the complex regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in vegetable tissues when MYB75/90/113/114 is incorporated (Gonzalez et al., 2008); when GL1/MYB23 is recruited, the complex regulates trichome initiation and branching (Kirik et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2008). In roots, WER is present in the complex that controls root hair patterning (Lee and Schiefelbein, 1999). Here, it is suggested that MYB82 joins in the complex and positively regulates trichome development.

R2R3-MYB transcription factors have a modular structure consisting of an N-terminal DNA-binding domain (the MYB domain) and an activation or repression domain usually located at the C-terminus. MYB82 is an R2R3-MYB family member. Transient expression assays indicated that the MYB82 protein was localized in the plant cell nucleus (Fig. 1A) and contained an activation domain in its C-terminus (Fig. 1B). MYB82 showed high sequence similarity with GL1 (Supplementary Fig. S1), implying a role in trichome development. Similar to GL1 overexpression, elevated expression of MYB82 caused reduced trichome numbers. In addition, both pGL1:MYB82g and pGL1:MYB82c promoted trichome formation in the gl1 mutant. These results demonstrate that MYB82 function is nearly equivalent to that of GL1. Because MYB82 is a transcription activation factor, the addition of the dominant repression domain (SRDX) to this protein almost completely suppressed trichome initiation; this result is similar to that obtained using 35S:GL1-SRDX transgenic plants (Fig. 2B). Overexpression of N-terminal truncated protein, which may competitively suppress the association of paralogous MYB-related proteins with target gene cis-regulatory elements, caused completely glabrous leaves. This result suggests that MYB82 is able to promote expression of trichome development-associated genes.

In addition to protein function similarity to GL1, MYB82 also displayed functional divergence. This work found that 35S:MYB82g and 35S:MYB82c have different effects on trichome development. Further analysis suggested that at least one intron is required for MYB82 under the control of the 35S promoter to affect trichome development. The first intron of GL1, similarly to WER and GaMYB2 genes, contains an MYB-binding box required for functional complementation of the gl1 mutant (Wang et al., 2004). No MYB-binding box was found in the introns of MYB82, although it is still possible that unidentified cis-regulatory elements are present. When MYB82 driven by the GL1 promoter was used to rescue the gl1 mutant, pGL1:MYB82g showed complete function complementation of the gl1 mutant, whereas pGL1:MYB82c only partially complemented the gl1 mutant. In contrast, pGL1:GL1g can complement the gl1 mutant, whereas pGL1:GLc has no contribution to mutant trichome initiation (Wang et al., 2004). The phenotypic difference between pGL1:MYB82c and pGL1:GL1c in the gl1 mutant background suggested that the exons of MYB82 contain cis-regulatory elements that are absent from GL1 exons. As expected, MYB82 contains a perfect MYB-binding box in the third exon. Mutation of this MYB-binding box disrupted pGL1:mMYB82c complementation of the gl1 mutant. Although MYB82 is a paralogue of GL1, MYB82 has evolved distinct cis-regulatory elements that directly affect its functions. Taken together, MYB82 shows functional divergence from GL1 in regard to trichome development.

R2R3-MYB subgroup 15 consists of three members: GL1, MYB23, and WER (Dubos et al., 2010). MYB82 and GL1 protein sequences are highly similar to one another. Subgroup-15 members have been confirmed to be incorporated into the WD40–bHLH–MYB complex (Zimmermann et al., 2004). The current work’s protein interaction analysis suggested that MYB82 also interacts with the bHLH transcription factor GL3, implying that MYB82 is involved in trichome development through participation in the WD40–bHLH–MYB transcription complex.

A contradictory phenomenon is the observation that overexpression of positive regulators of trichome development, GL1 and MYB23, as well as MYB82, often cause trichome number reductions (Larkin et al., 1994; Kirik et al., 2001). The current work revealed that MYB82 and GL1 can form homodimers or heterodimers at the N-terminal R2R3-MYB domain. It has been confirmed that, in the WD40–bHLH–MYB complex, MYB interacts with bHLH at its MYB domain (Grotewold et al., 2000). It is therefore very likely that overexpression of the R2R3-MYB protein results in increased production of MYB homodimers or heterodimers, which may competitively lead to fewer WD40–bHLH–MYB complexes, and, consequently, to a reduction in trichome numbers.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Supplementary Fig. S1. Expression levels of MYB82 in amiR-myb82 transgenic plants.

Supplementary Fig. S2. Expression levels of GL2 in different transgenic plants.

Supplementary Fig. S3. MYB proteins containing the conserved signature motif ([DE]Lx2[RK]x3Lx6Lx3R).

Supplementary Table S1. Expression and phenotype analysis of transgenic plants.

Supplementary Table S2. Primer sequences.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31100186) and the West Light Foundation of CAS. The authors thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which helped to improve the manuscript. They thank the Arabidopsis Resource Center at the Ohio State University for the T-DNA insertion mutants.

References

- Bernhardt C, Lee MM, Gonzalez A, Zhang F, Lloyd A, Schiefelbein J. 2003. The bHLH genes GLABRA3 (GL3) and ENHANCER OF GLABRA3 (EGL3) specify epidermal cell fate in the Arabidopsis root. Development 130, 6431–6439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubos C, Stracke R, Grotewold E, Weisshaar B, Martin C, Lepiniec L. 2010. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis . Trends in Plant Science 15, 573–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esch JJ, Chen M, Sanders M, Hillestad M, Ndkium S, Idelkope B, Neizer J, Marks MD. 2003. A contradictory GLABRA3 allele helps define gene interactions controlling trichome development in Arabidopsis . Development 130, 5885–5894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esch JJ, Chen MA, Hillestad M, Marks MD. 2004. Comparison of TRY and the closely related At1g01380 gene in controlling Arabidopsis trichome patterning. The Plant Journal 40, 860–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre-D’Amare AR, Pognonec P, Roeder RG, Burley S. 1994. Structure and function of the b/HLH/Z domain of USF. EMBO Journal 13, 180–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyvie MJ, Murray JA, Kilby NJ. 2000. Mosaic analysis of GL2 gene expression and cell layer autonomy during the specification of Arabidopsis leaf trichomes. Genesis 28, 68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan L, Xia K, Chen JG, Wang S. 2011. Functional characterization of TRICHOMELESS2, a new single-repeat R3 MYB transcription factor in the regulation of trichome patterning in Arabidopsis . BMC Plant Biology 11, 176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Zhao M, Leavitt JM, Lloyd AM. 2008. Regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway by the TTG1/bHLH/Myb transcriptional complex in Arabidopsis seedlings. The Plant Journal 53, 814–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotewold E, Sainz MB, Tagliani L, Hernandez JM, Bowen B, Chandler VL. 2000. Identification of the residues in the Myb domain of maize C1 that specify the interaction with the bHLH cofactor R. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 97, 13579–13584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Liang G, Li Y, Wang F, Yu DQ. 2014. Two young miRNAs originating from target duplication mediate nitrogen starvation adaptation via regulation of glucosinolate synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Physiology 164, 853–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsu K, Matsui K, Koyama T, Ohme-Takagi M. 2003. Dominant repression of target genes by chimeric repressors that include the EAR motif, a repression domain, in Arabidopsis . The Plant Journal 34, 733–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsu K, Mitsuda N, Matsui K, Ohme-Takagi M. 2004. Identification of the minimal repression domain of SUPERMAN shows that the DLELRL hexapeptide is both necessary and sufficient for repression of transcription in Arabidopsis . Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 321, 172–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T, Hattori S, Sano R, et al. 2007. Arabidopsis TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2 is directly regulated by R2R3-MYB transcription factors and is involved in regulation of GLABRA2 transcription in epidermal differentiation. The Plant Cell 19, 2531–2543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T, Kurata T, Okada K, Wada T. 2008. A genetic regulatory network in the development of trichomes and root hairs. Annual Review of Plant Biology 59, 365–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CS, Kolevski B, Smyth DR. 2002. TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2, a trichome and seed coat development gene of Arabidopsis, encodes a WRKY transcription factor. The Plant Cell 14, 1359–1375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik V, Schnittger A, Radchuk V, Adler K, Hulskamp M, Baumlein H. 2001. Ectopic expression of the Arabidopsis AtMYB23 gene induces differentiation of trichome cells. Developmental Biology 235, 366–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik V, Simon M, Hulskamp M, Schiefelbein J. 2004a. The ENHANCER of TRY and CPC1 (ETC1) gene acts redundantly with TRIPTYCHON and CAPRICE in trichome and root hair cell patterning in Arabidopsis . Developmental Biology 268, 506–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik V, Simon M, Wester K, Schiefelbein J, Hulskamp M. 2004b. ENHANCER of TRY and CPC 2 (ETC2) reveals redundancy in the region-specific control of trichome development of Arabidopsis . Plant Molecular Biology 55, 389–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik V, Lee MM, Wester K, Herrmann U, Zheng Z, Oppenheimer D, Schiefelbein J, Hulskamp M. 2005. Functional diversification of MYB23 and GL1 genes in trichome morphogenesis and initiation. Development 132, 1477–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin JC, Oppenheimer DG, Lloyd AM, Paparozzi ET, Marks MD. 1994. Roles of the GLABROUS1 and TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA genes in Arabidopsis trichome development. The Plant Cell 6, 1065–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MM, Schiefelbein J. 1999. WEREWOLF, a MYB-related protein in Arabidopsis, is a position-dependent regulator of epidermal cell patterning. Cell 99, 473–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MM, Schiefelbein J. 2001. Developmentally distinct MYB genes encode functionally equivalent proteins in Arabidopsis . Development 128, 1539–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G, He H, Li Y, Yu DQ. 2012. A new strategy for construction of artificial miRNA vectors in Arabidopsis. Planta 235, 1421–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marricio R, Rausher MD. 1997. Experimental manipulation of putative selective agents provides evidence for the role of natural enemies in the evolution of plant defense. Evolution 51, 1435–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masucci JD, Rerie WG, Foreman DR, Zhang M, Galway ME, Marks MD, et al. 1996. The homeobox gene GLABRA2 is required for position-dependent cell differentiation in the root epidermis of Arabidopsis thaliana . Development 122, 1253–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morohashi K, Zhao M, Yang M, Read B, Lloyd A, Lamb R, Grotewold E. 2007. Participation of the Arabidopsis bHLH factor GL3 in trichome initiation regulatory events. Plant Physiology 145, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murre C, McCaw PS, Baltimore D. 1989. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD and myc proteins. Cell 56, 777–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi Y, Oka A, Ruberti I, Morelli G, Aoyama T. 2002. Entopically additive expression of GLABRA2 alters the frequency and spacing of trichome initiation. The Plant Journal 29, 359–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer DG, Herman PL, Sivakumaran S, Esch J, Marks MD. 1991. A myb gene required for leaf trichome differentiation in Arabidopsis is expressed in stipules. Cell 67, 483–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne CT, Zhang F, Lloyd AM. 2000. GL3 encodes a bHLH protein that regulates trichome development in Arabidopsis through interaction with GL1 and TTG1. Genetics 156, 1349–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rerie WG, Feldmann KA, Marks MD. 1994. The GLABRA2 gene encodes a homeo domain protein required for normal trichome development in Arabidopsis . Genes and Development 8, 1388–1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio V, Linhares F, Solano R, Martín AC, Iglesias J, Leyva A, Paz-Ares J. 2001. A conserved MYB transcription factor involved in phosphate starvation signaling both in vascular plants and in unicellular algae. Genes and Development 15, 2122–2133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serna L, Martin C. 2006. Trichomes: different regulatory networks lead to convergent structures. Trends in Plant Science 11, 274–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellmann S, Hülskamp M, Uhrig J. 2007. Epidermal pattern formation in the root and shoot of Arabidopsis . Biochemical Society Transactions 35, 146–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Qi T, Huang H, Ren Q, Wu D, Chang C, Peng W, Liu Y, Peng J, Xie D. 2011. The Jasmonate-ZIM domain proteins interact with the R2R3-MYB transcription factors MYB21 and MYB24 to affect Jasmonate-regulated stamen development in Arabidopsis . The Plant Cell 23, 1000–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer A, Bollman KM, Poethig RS. 1997. Phase change and the regulation of trichome distribution in Arabidopsis thaliana . Development 124, 645–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson C, Myakishev M, Acharya A, Mir AA, Moll JR, Bonovich M. 2002. Classification of human B-ZIP proteins based on dimerization properties. Molecular and Cellular Biology 22, 6321–6335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AR, Davison PA, Bolognesi-Winfield AC, James CM, Srinivasan N, Blundell TL, Esch JJ, Marks MD, Gray JC. 1999. The TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 locus, which regulates trichome differentiation and anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis, encodes a WD40 repeat protein. The Plant Cell 11, 1337–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wang JW, Yu N, Li CH, Luo B, Gou JY, Wang LJ, Chen XY. 2004. Control of plant trichome development by a cotton fiber MYB gene. The Plant Cell 16, 2323–2334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Kwak SH, Zeng Q, Ellis BE, Chen XY, Schiefelbein J, Chen JG. 2007. TRICHOMELESS1 regulates trichome patterning by suppressing GLABRA1 in Arabidopsis. Development 134, 3873–3882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wester K, Digiuni S, Geier F, Timmer J, Fleck C, Hülskamp M. 2009. Functional diversity of R3 single-repeat genes in trichome development. Development 136, 1487–1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Gonzalez A, Zhao M, Payne CT, Lloyd A. 2003. A network of redundant bHLH proteins functions in all TTG1-dependent pathways of Arabidopsis . Development 130, 4859–4869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Morohashi K, Hatlestad G, Grotewold E, Lloyd A. 2008. The TTG1-bHLH-MYB complex controls trichome cell fate and patterning through direct targeting of regulatory loci. Development 135, 1991–1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann IM, Heim MA, Weisshaar B, Uhrig JF. 2004. Comprehensive identification of Arabidopsis thaliana MYB transcription factors interacting with R/B-like BHLH proteins. The Plant Journal 40, 22–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.