Liver cancer is the only cancer in Canada that has witnessed a statistically significant rise in mortality rate, yet survival data suggest that identification and treatment of individuals with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) continues to be inadequate despite the cost effectiveness of ultrasound surveillance of at-risk populations. Prompted by anecdotal evidence that HCC patients referred to their hospital network from outside centres were more often in the palliative stages of disease than patients within their surveillance group, the authors of this study aimed to determine the factors associated with referral in the palliative stage among patients whose tumours were discovered elsewhere. Study findings between the referred and internal groups yielded striking differences.

Keywords: Cirrhosis, Hepatitis, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Surveillance

Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To determine whether there is a significant difference in tumour stage between patients initially found with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) at a tertiary hepatobiliary centre and patients referred with tumours detected elsewhere; and to determine variables associated with referral in a palliative stage.

METHODS:

A retrospective review of 12,199 patients seen at a liver clinic over a 10.5-year period revealed 236 patients with HCC first detected internally (internal) and 163 who were referred with a known mass (referred). All patients were staged at the time of treatment using the Milan criteria for transplantation and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system. Curative disease was defined as BCLC stages 0 and A. In the referred group, univariate and multivariate analyses were used to determine which of the following factors were significantly associated with presentation in a palliative stage: age, sex, ethnicity, cause of liver disease, presence of cirrhosis, location of residence and quintile of neighbourhood income.

RESULTS:

In comparing the internal versus referred patients, significant differences were found in the proportion of patients fulfilling Milan criteria (72% versus 36%), those with curative disease (75% versus 49%) and those with very early stage tumour (BCLC stage 0, 23% versus 7%); all differences were statistically significant (P<0.001). In patients referred for treatment of HCC from an outside institution, none of the variables tested were associated with presentation in a palliative stage.

CONCLUSION:

Patients with HCC referred to a liver treatment centre were more likely to be in palliative stages than those whose tumour was detected internally.

Abstract

OBJECTIF :

Déterminer si le stade de tumeur présente une différence importante entre les patients qui se font diagnostiquer un carcinome hépatocellulaire (CHC) dans un centre hépatobiliaire de soins tertiaires et ceux qui sont aiguillés parce que leur tumeur a été décelée ailleurs; déterminer les variables associées à l’aiguillage en phase palliative.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Une analyse rétrospective de 12 199 patients vus à une clinique hépatique pendant une période de 10,5 ans a révélé que 236 patients ayant un CHC avaient été dépistés à l’hôpital (à l’interne) et 163 avaient été aiguillés parce qu’ils avaient une masse connue (aiguillés). Le stade des patients était établi au moment du traitement au moyen des critères de transplantation de Milan et du système de classification de la clinique de cancer hépatique de Barcelone (CCHB). Une maladie curative était définie comme les stades 0 et A de la CCHB. Dans le groupe aiguillé, les analyses univariées et multivariées ont permis de déterminer lesquels des facteurs suivants s’associaient de manière significative à la présentation en phase palliative : âge, sexe, ethnie, cause de maladie hépatique, présence de cirrhose, lieu de résidence et quintile du revenu du quartier.

RÉSULTATS :

En comparant les patients à l’interne aux patients aiguillés, les chercheurs ont constaté des différences importantes dans la proportion de patients qui respectaient les critères de Milan (72 % par rapport à 36 %), qui avaient une maladie curative (75 % par rapport à 49 %) ou qui avaient une tumeur de stade précoce (stade 0 de la CCHB, 23 % par rapport à 7 %). Toutes les différences étaient statistiquement significatives (P<0,001). Chez les patients aiguillés pour le traitement d’un CHC à partir d’un établissement externe, aucune des variables examinées ne s’associait à une présentation en phase palliative.

CONCLUSION :

Les patients ayant un CHC qui étaient aiguillés vers un centre de traitement hépatique étaient plus susceptibles d’être en phase palliative que ceux dont la tumeur avait été décelée à l’interne.

Of the 25 most common cancers in Canada, liver cancer is the only cancer with a statistically significant rise in mortality rate; the Canadian age-adjusted incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was projected to rise by 73% in males and 28% in females from 1996 to 2015 (1,2). Ultrasound surveillance of populations at risk for HCC has not been promoted by Canadian governmental health agencies but has been considered to be the standard of care by the hepatology community both in Canada and internationally (3–7). Supporting surveillance are its cost effectiveness and reported decreased mortality in a randomized controlled trial (8–10). Despite a universal health care system, survival data suggest that the identification and/or treatment of patients with HCC are lagging in Canada. The latest statistics reveal that the highest reported survival rate of patients with HCC is in Japan, where the five-year survival rate is 39% to 44%, whereas it is 26% in British Columbia and 22% in Ontario (11–14). While the Canadian urban population contains a unique mix of ethnicities and risk factors for HCC, there have been no previous studies investigating HCC stage at presentation in Canada.

Approximately 3000 patients undergo annual HCC surveillance within the University Hospital Network (Toronto, Ontario). We have anecdotally noted that patients with HCC referred to our centre for treatment are more often in palliative stages of disease than those within our own surveillance group who develop HCC. Our hospital network is the only designated regional treatment centre for HCC and, therefore, nearly all HCCs discovered in the region, regardless of the stage, are referred to our centre for treatment, minimizing referral bias. Therefore, we undertook a study to establish whether patients referred to us with HCC were significantly more likely to present in a palliative stage compared with those whose HCC was discovered through our own hospital. Furthermore, we aimed to determine which independent variables were associated with referral in the palliative stage among patients referred to our centre for treatment.

METHODS

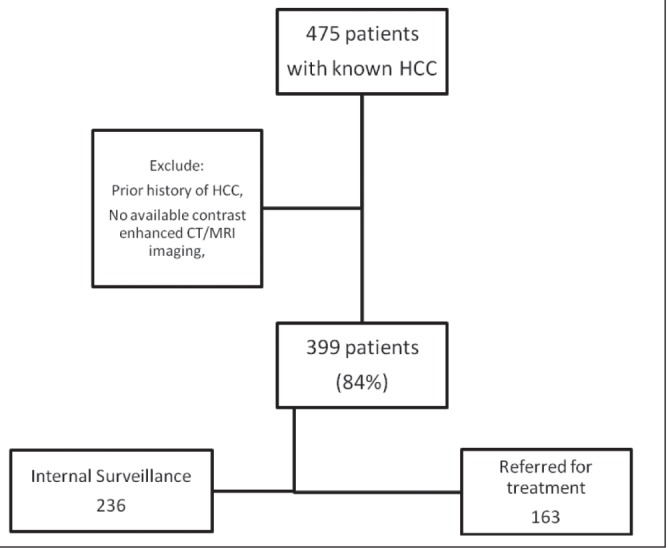

A retrospective review of charts of 12,199 patients seen at the liver clinic at one of the authors’ hospitals (Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, Ontario) from January 2000 to June 2010 revealed 475 patients with a diagnosis of HCC. This single hospital was selected because the records of the liver clinic were in electronic fromat. Patients with a history of HCC or without available contrast-enhanced computed tomography/ magnetic resonance imaging data were excluded (Figure 1). Patients were divided into ‘internal’ (tumour first discovered in the authors’ institution) or ‘referred’ (patient referred with a known hepatic mass) groups based on chart review and cross-confirmed by reviewing the indication for imaging at the authors’ institution. Of the 236 internal patients, 201 (85.1%) were undergoing ultrasound surveillance at the authors’ institution and distributed as follows: regular surveillance (≤12 months interval between last two surveillance scans [n=109]), irregular surveillance (>12 months [n=38]) or first surveillance (tumour detected on first scan [n=54]).

Figure 1).

Flowchart of patient population. CT Computed tomography; HCC Hepatocellular carcinoma; MRI Magnetic resonance imaging

The diagnosis of HCC was confirmed for all patients using the following criteria: updated American Association for Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) HCC management guidelines’ imaging diagnostic criteria of one positive contrast-enhanced imaging scan in at-risk patients (5); positive histopathology from core biopsy or explant specimens; or recurrence after treatment of tumour. All relevant imaging data were directly and retrospectively reviewed by a fellowship-trained abdominal imager to ensure compliance with the latest imaging criteria and to confirm staging.

Outcome measures

The stage of disease based on the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging classification was used as an outcome measure (15). Curative disease was defined as early BCLC stages 0 (one nodule <2 cm) or A (one resectable nodule of any size or three nodules <3 cm). Palliative disease was defined in patients with the advanced stages B to D. The Milan criteria for treatment of HCC by transplantation were used as an additional outcome measure, with early disease defined as fulfilling the criteria of one nodule <5 cm or three nodules <3 cm without venous invasion or distant metastases (16). To ensure a fair comparison of tumour stage among referred and internal surveillance patients, the imaging available on assessment for treatment at multidisciplinary tumour board was used for all patients. Therefore, if a tumour had been discovered earlier by surveillance but had been followed, the tumour stage at time of treatment rather than time of discovery was used.

Variables potentially associated with presentation in a palliative stage

In the referred group of patients, the following variables were tested for an association with presentation in a palliative stage: age, sex, ethnicity, cause of liver disease, presence of cirrhosis, location of residence and quintile of neighbourhood income. Due to the limited number of patients in some subcategories, certain variables were grouped for the analysis. The surveillance history of the referred patients was unavailable due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Ethnicity was divided into two groups: Caucasian (European descent) and others (including East and Southeast Asians, African, Middle-Eastern, South-Asian, Caribbean and Latin American). Causes of liver disease included chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, other causes and multiple causes (patients with more than one cause of disease). The Child-Pugh score was used for severity of liver disease with non-cirrhotic patients grouped with Child-Pugh A versus patients with Child-Pugh B and C scores. Year of detection was divided into two groups – 2000 to 2005 and 2006 to 2010 – to determine the effect of implementation of the first AASLD HCC guidelines (in 2005) along with installation of the latest generation of scanners at the authors’ institution (in 2006). Patients were divided based on their residence in metropolitan (greater Toronto [Ontario] area) versus beyond metropolitan groups to determine whether there was a difference in urban versus rural populations. Finally, surveillance frequency was grouped into ≤12 months (adequate) and >12 months (inadequate) based on the interval between last and immediately previous surveillance scans. Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics

|

Patients

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Internal (n=236) | Referred (n=163) | |

| Age, years | ||

| Mean ± SD | 61.6±10.8) | 61.2±11.3) |

| Median (range) | 61 (26–86) | 61 (31–85) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African | 7 (3) | 3 (2) |

| Asian, East/Southeast | 63 (27) | 81 (50) |

| Asian, South | 11 (5) | 8 (5) |

| Caribbean | 3 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Caucasian | 143 (61) | 61 (37) |

| Latin American | 3 (1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Middle Eastern | 5 (2) | 5 (3) |

| North American Natives | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) |

| Cause(s) of liver disease | ||

| Hepatitis C virus | 105 (44) | 51 (31) |

| Hepatitis B virus | 58 (25) | 82 (50) |

| More than one cause | 36 (15) | 14 (9) |

| Alcohol | 22 (9) | 5 (3) |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | 8 (3) | 2 (1) |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 2 (1) | – |

| Hemochromatosis | – | 1 (0.6) |

| Alagille syndrome | 1 (0.4) | – |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 1 (0.4) | – |

| Budd-Chiari syndrome | 1 (0.4) | – |

| Unknown | 2 (1) | 8 (5) |

| Cirrhosis | ||

| Yes | 229 (97) | 150 (92) |

| Symptomatic presentation | ||

| Yes | 12 (5) | 7 (4) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated

Statistical methods

Associations with referral status were examined using the Fisher’s exact test (for cirrhosis), t test (for age) and χ2 test (for all other variables). χ2 and logistic regression analyses were used to examine associations with presentation in a palliative stage. For the latter analysis, two outcome measures were used, as described (BCLC stage 0/A versus B/C/D; fulfill Milan criteria yes versus no). Patients’ quintile of neighbourhood income and region of residence were derived using the Postal Code Conversion File + Version 5 (PCCF+) (17). PCCF+ is a series of files created by Statistics Canada based on the most recent Canadian census data and assigns geographical identifiers based on postal codes. For the purposes of the present study, patients’ quintile of neighbourhood income was used as a proxy measure of personal income of study participants, while region of residence was classified as within or beyond the metropolitan area (greater Toronto area).

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, USA) and SPSS version 17.0 (IBM Corporation, USA) for Windows 2008 (Microsoft Corporation, USA); P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant associations.

RESULTS

Comparison of referred and internal patients

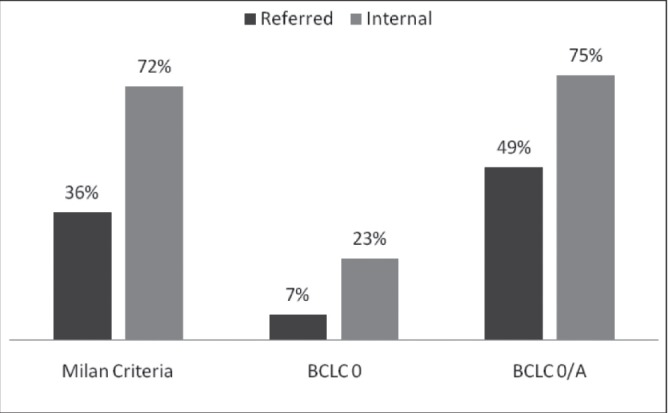

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of internal versus referred patients. Significant differences were apparent between referred and internal patients in the proportion of Caucasian patients (61% versus 37%; P<0.001), of those fulfilling Milan criteria (36% versus 72%; P<0.001) and those with curative BCLC stages 0 and A (49% versus 75%; P<0.001). In addition, a significantly lower proportion of referred patients (12 of 163 [7%]) had their tumour discovered at the very early BCLC stage (ie, stage 0, <2 cm) compared with internal patients (55 of 236 [23%]; P<0.001), data not shown in Table 1). Figure 2 illustrates the differences between internal and referred patients.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of internal and referred patients

| Internal (n=236) | Referred (n=163) | P | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 44 (19) | 35 (21) | 0.486 | 1.19 (0.73–1.96) |

| Male | 192 (81) | 128 (79) | 1.00 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 143 (61) | 61 (37) | <0.001 | 1.00 |

| Other | 93 (39) | 102 (63) | 2.57 (1.71–3.88) | |

| Cirrhosis | ||||

| No | 7 (3) | 13 (8) | 0.024 | 2.83 (1.11–7.27) |

| Yes | 229 (97) | 150 (92) | 1.00 | |

| BCLC stage at treatment | ||||

| 0/A | 178 (75) | 80 (49) | <0.001 | 1.00 |

| B/C/D | 58 (25) | 83 (51) | 3.18 (2.08–4.88) | |

| Milan criteria | ||||

| No | 65 (28) | 104 (64) | <0.001 | 4.64 (3.02–7.12) |

| Yes | 171 (72) | 59 (36) | 1.00 | |

| Income quintile (postal code) | ||||

| 1 (lowest) | 56 (24) | 37 (23) | 0.734 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 53 (22) | 42 (26) | 1.20 (0.67–2.14) | |

| 3 | 41 (17) | 32 (20) | 1.18 (0.64–2.20) | |

| 4 | 39 (17) | 32 (20) | 1.24 (0.67–2.32) | |

| 5 (highest) | 36 (15) | 19 (12) | 0.80 (0.40–1.60) | |

| Unmatchable | 11 (5) | 1 (0.6) | 0.14 (0.02–1.11) | |

| Cause(s) of liver disease | ||||

| Hepatitis B virus | 58 (25) | 82 (50) | <0.001 | 2.90 (1.53–5.52) |

| Hepatitis C virus | 105 (44) | 51 (31) | 1.00 (0.52–1.90) | |

| Combined | 34 (14) | 11 (7) | 0.66 (0.28–1.59) | |

| Other/unknown | 39 (17) | 19 (12) | 1.00 | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 61.6±10.8 | 61.2±11.3 | 0.627 | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) |

| Median (range) | 61 (26–86) | 61 (31–85) | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Beyond metropolitan* | 32 (14) | 26 (16) | 0.505 | 1.21 (0.69–2.12) |

| Metropolitan* | 204 (86) | 137 (84) | 1.00 | |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Greater Toronto (Ontario) area. BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

Figure 2).

Comparison of heaptocellular carcinoma stage in referred versus internal patients (all differences are statististically significant [P<0.001]). BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

Potential determinants of early stage presentation in referred patients

Tables 3 and 4 summarize the results of univariate analyses in predicting presentation in an early stage among referred patients using BCLC staging (Table 3) and Milan criteria (Table 4). Multivariate analysis was not performed because none of the variables reached significance in univariate analysis (unadjusted). There was a trend among non-Caucasian patients to present in curable stages using both BCLC and Milan criteria, but this did not reach statistical significance (P=0.11 and P=0.09, respectively).

TABLE 3.

Predicting presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma at an early stage using the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system

|

BCLC

|

P | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0/A (n=80) | B/C/D (n=83) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 16 (20) | 19 (23) | 0.653 | 0.84 (0.40–1.78) |

| Male | 64 (80) | 64 (77) | 1.00 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 25 (31) | 36 (43) | 0.110 | 1.00 |

| Other | 55 (69) | 47 (57) | 1.69 (0.89–3.20) | |

| Cirrhosis | ||||

| No | 9 (11) | 5 (6) | 0.349 | 1.73 (0.54–5.54) |

| Yes | 72 (90) | 78 (94) | 1.00 | |

| Income quintile (postal code) | ||||

| 1 (lowest) | 16 (20) | 21 (25) | 0.948 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 22 (28) | 20 (24) | 1.44 (0.59–3.51) | |

| 3 | 16 (20) | 16 (19) | 1.31 (0.51–3.40) | |

| 4 | 16 (20) | 16 (19) | 1.31 (0.51–3.40) | |

| 5 (highest) | 9 (11) | 10 (12) | 1.18 (0.39–3.59) | |

| Unmatchable | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Cause(s) of liver disease | ||||

| Hepatitis B virus | 41 (51) | 41 (49) | 0.991 | 1.11 (0.41–3.02) |

| Hepatitis C virus | 25 (31) | 26 (31) | 1.07 (0.37–3.07) | |

| Combined | 5 (6) | 6 (7) | 0.93 (0.21–4.11) | |

| Other/unknown | 9 (11) | 10 (12) | 1.00 | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 60.8±12 | 61.6± 10.7 | 0.638 | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) |

| Median (range) | 60 (31–85) | 61 (34–83) | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Beyond metropolitan* | 13 (16) | 13 (16) | 0.918 | 1.05 (0.45–2.42) |

| Metropolitan* | 67 (84) | 70 (84) | 1.00 | |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Greater Toronto (Ontario) area

TABLE 4.

Predicting presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma at an early stage using the Milan criteria for transplantation

|

Milan criteria

|

P | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=59) | No (n=104) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 14 (24) | 21 (20) | 0.597 | 1.23 (0.57–2.65) |

| Male | 45 (76) | 83 (80) | 1.00 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 17 (29) | 44 (42) | 0.087 | 1.00 |

| Other | 42 (71) | 60 (58) | 1.81 (0.91–3.59) | |

| Asian | 31 (53) | 50 (48) | 0.699 | 1.00 |

| Non-Asian | 28 (47) | 54 (52) | 0.84 (0.44–1.59) | |

| Cirrhosis | ||||

| No | 2 (3) | 11 (11) | 0.137 | 0.30 (0.06–1.39) |

| Yes | 57 (97) | 93 (89) | 1.00 | |

| Income quintile (postal code) | ||||

| 1 (lowest) | 9 (15) | 28 (27) | 0.570* | 1.00 |

| 2 | 17 (29) | 25 (24) | 2.12 (0.80–5.59) | |

| 3 | 12 (20) | 20 (19) | 1.87 (0.66–5.27) | |

| 4 | 12 (20) | 20 (19) | 1.87 (0.66–5.27) | |

| 5 (highest) | 8 (14) | 11 (11) | 2.26 (0.70–7.37) | |

| Unmatchable | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | ||

| Cause(s) of liver disease | ||||

| Hepatitis B virus | 30 (51) | 52 (50) | 0.977 | 1.25 (0.43–3.63) |

| Hepatitis C virus | 19 (32) | 32 (31) | 1.29 (0.42–3.95) | |

| Combined | 4 (7) | 7 (7) | 1.24 (0.26–5.91) | |

| Other/unknown | 6 (10) | 13 (13) | 1.00 | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 61.5±12.1 | 61.0±10.9 | 0.810 | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) |

| Median (range) | 60 (31–85) | 61 (34–83) | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Beyond metropolitan* | 8 (14) | 18 (17) | 0.530 | 0.75 (0.30–1.85) |

| Metropolitan* | 51 (86) | 86 (83) | 1.00 | |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Greater Toronto (Ontario) area

DISCUSSION

The present study yielded two key findings. The first was that there was a significantly higher proportion of patients with incurable HCC among those whose tumours were discovered elsewhere compared with those whose cancer was discovered at our institution. The second is that cause of liver disease, ethnicity nor any of the other variables tested appeared to be a significant determinant of this late presentation in the referred group.

The differences between the tumour stage of referred versus internal group of patients is striking. The proportion of those who fulfilled the Milan criteria – so called ‘early stage cancers’ – among the internal patients (72%) was double that of the referred patients (36%). Patients had a 4.6 times higher odds of having a tumour discovered according to Milan criteria when they were undergoing care in our hospital. The odds were less (OR 3.18 [95% CI 2.08 to 4.88]) when using the BCLC staging system as an end point, but this is because BCLC stage A includes single operable tumours >5 cm in addition to those meeting the Milan criteria.

Which factors are associated with the relatively late presentation in most of the referred patients? Among the seven variables tested, none showed a significant association with presentation with advanced HCC (Tables 3 and 4). Interestingly, neither residence in the greater Toronto area nor quintile of neighbourhood income (a marker of personal income) correlated with this late presentation. Caucasians and East/Southeast Asians comprised the two largest ethnic groups in the present study, accounting for 87% of the referred patient group. Neither ethnic group had any advantage in early presentation fulfilling the Milan criteria (Table 4). Therefore, ethnicity was also not significantly associated with the stage of presentation.

The one variable that could not be examined was the referred patients’ HCC surveillance history; this is the most likely difference between the internal and referred populations. The internal patient population included everyone whose HCC was discovered at our institution, also counting those who presented symptomatically or with terminal liver failure (BCLC stage D). However, most of the internal patients were undergoing some surveillance. A low rate of HCC surveillance and/or its low effectiveness among referred patients are the most likely causes of the differences in the two populations. This assertion is supported by other international studies that have described a similar difference in presenting tumour stage of patients referred for treatment compared with those within a surveillance population (18–21). The present study was the first to assess the Canadian experience with its unique mix of risk factors. Ineffective surveillance may be due to low sensitivity, incorrect method (ie, not by ultrasound) or improper management. The incidence and mortality rates of HCC are diluted in provincial and national statistics but much of the HCC at-risk population reside in the few large Canadian urban centres (22). This concentration also renders targeted interventions potentially more cost effective. By identifying individuals at risk and making effective surveillance widespread, we believe that stage migration is achievable.

Strengths and limitations

Because our hospital is the only designated regional centre for HCC treatment, referral bias is likely to be small, especially because nearly all potentially curative therapies, including all liver transplants in the region, are performed here. Nevertheless, a small but unknown volume of surgical interventions are performed outside our institution, raising the possibility that the referred population would have a higher proportion of more advanced tumours. Counteracting this bias is the fact that external patients presenting with end-stage HCC are less likely to be referred because their survival is <3 months and some would have died before staging at our institution (15). As part of the internal group of patients, we included all newly discovered HCCs found in our hospital, even if the patients were not part of our surveillance group and presented symptomatically with an end-stage HCC (ie, BCLC stage D). Retrospective studies assessing survival in a surveillance setting are subject to both lead-time and length-time biases. By using tumour stage at the time of treatment rather than survival as an end point, we hoped to diminish both of these. Finally, the surveillance history of referred patients could not be examined in the present retrospective study; therefore, we cannot determine whether the cause of the late presentation for treatment was related to a lack of surveillance, its ineffectiveness or improper management once a nodule was found.

CONCLUSION

The present study shows a significant worsening of HCC stage at time of treatment in patients not undergoing care in a health care centre specialized in liver diseases. Lack of, or ineffective surveillance practice in the community setting is the likely cause of this discrepancy. Targeted public-health interventions are needed to address this growing problem.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: This study was not funded by grants or other financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee on Cancer Statistics . Canadian Cancer Statistics 2012. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pocobelli G, Cook LS, Brant R, Lee SS. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence trends in Canada: Analysis by birth cohort and period of diagnosis. Liver Int. 2008;28:1272–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asmis T, Balaa F, Scully L, et al. Diagnosis and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: Results of a consensus meeting of The Ottawa Hospital Cancer Centre. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:6–12. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i2.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherman M, Bain V, Villeneuve JP, et al. The management of chronic viral hepatitis: A Canadian consensus conference 2004. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:715–28. doi: 10.1155/2004/201031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: An update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–2. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Omata M, Lesmana LA, Tateishi R, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:439–74. doi: 10.1007/s12072-010-9165-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang BH, Yang BH, Tang ZY. Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:417–22. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersson KL, Salomon JA, Goldie SJ, Chung RT. Cost effectiveness of alternative surveillance strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1418–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruggeri M. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Cost-effectiveness of screening. A systematic review. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2012;5:49–54. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S18677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikai I, Kudo M, Arii S, et al. Report of the 18th follow-up survey of primary liver cancer in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:1043–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2010.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.BCCA . Survival Statistics 2007. BC Cancer Agency; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cancer Care Ontario Cancer Fact: The most fatal cancers in Ontario. Apr, 2011. < www.cancercare.on.ca/cancerfacts/> (Accessed January 14, 2013)

- 14.Saito H, Masuda T, Tada S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Keio affiliated hospitals – diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of this disease. Keio J Med. 2009;58:161–75. doi: 10.2302/kjm.58.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forner A, Hessheimer AJ, Isabel Real M, Bruix J. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;60:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Statistics Canada Geography Division. Postal code conversion file. 2011. < www5.statcan.gc.ca/bsolc/olc-cel/olc-cel?lang=eng&catno=82F0086X> (Accessed January 14, 2013)

- 18.Stravitz RT, Heuman DM, Chand N, et al. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis improves outcome. Am J Med. 2008;121:119–26. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo YH, Lu SN, Chen CL, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance and appropriate treatment options improve survival for patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:744–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noda I, Kitamoto M, Nakahara H, et al. Regular surveillance by imaging for early detection and better prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients infected with hepatitis C virus. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:105–12. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian MY, Yuwei JR, Angus P, Schelleman T, Johnson L, Gow P. Efficacy and cost of a hepatocellular carcinoma screening program at an Australian teaching hospital. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:951–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Yi Q, Mao Y. Cluster of liver cancer and immigration: A geographic analysis of incidence data for Ontario 1998–2002. Int J Health Geogr. 2008;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]