The multidisciplinary approach required to treat patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) involves contributions from physicians, nurses and dieticians, among others. Given the fluctuating nature of IBD, and the need for both maintenance therapy and acute interventions to treat disease flares, the roles played by registered nurses and nurse practitioners have emerged as central to managing patients with IBD in studies from the United Kingdom. The authors of this study developed a survey with the aim of similarly assessing nurses’ roles in the Canadian setting.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Nursing, Nursing roles

Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVE:

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic relapsing illness primarily including Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. The disease course often fluctuates over time, and requires maintenance therapy and acute interventions to target disease flares. IBD management requires a multidisciplinary approach, with care from physicians, nurses, dieticians, social workers and psychologists. Because nurses play a pivotal role in managing chronic disease, the aim of the present study was to assess and determine how many nurses work primarily with IBD patients in Canada.

METHODS:

A 29-question survey was developed using an Internet-based survey tool (www.surveymonkey.com) to investigate nursing demographics, IBD nursing roles and nursing services provided across Canada. Distribution included the Canadian Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates, the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology, Progress (AbbVie Corporation, USA) and BioAdvance (Janssen Inc, USA) coordinators (via e-mail), and online availability for 15 weeks.

RESULTS:

Of 275 survey respondents, 98.2% were female nurses, with 68.7% employed in full-time positions. Among them, 42.5% were between 51 and 60 years of age, and 32.4% were between 41 and 50 years of age. In addition, 53.8% were diploma-prepared registered nurses, 35.3% were Baccalaureate-prepared nurses and 4.4% were Masters-prepared nurses. Almost one-half (44% [n=121]) were employed in Ontario, followed by 19.6% (n=54) in Alberta and 9.1% (n=25) in British Columbia. All provinces were represented with the exception of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories. Forty-three per cent (n=119) of nurses identified as working in endoscopy units. Of the 90% who responded as working with IBD patients, only 30% (n=79) had a primary role in IBD care. Among these 79 nurses with a primary role in IBD care, 79.7% worked with the adult population, 10.1% with the pediatric population, and 10.1% worked with both adult and pediatric patients. Their major service was an outpatient setting (67.1%).

CONCLUSIONS:

Survey results showed that only a small percentage of Canadian gastroenterology nurses provide clinical IBD care. Many have multiple roles and responsibilities, and provide a variety of services. The exact depth of care and service is unclear and further study is needed.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE ET OBJECTIF :

Les maladies inflammatoires de l’intestin (MII), des maladies chroniques récidivantes, incluent surtout la maladie de Crohn et la colite ulcéreuse. Elles fluctuent souvent au fil du temps et exigent un traitement d’entretien et des interventions aiguës pour cibler les exacerbations. Il faut adopter une démarche multidisciplinaire pour prendre en charge les MII, qui incluent les soins de médecins, d’infirmières, de diététistes, de travailleurs sociaux et de psychologues. Puisque les infirmières jouent un rôle essentiel dans la prise en charge des maladies chroniques, la présente étude visait à évaluer et à déterminer le nombre d’infirmières qui travaillent surtout avec des patients atteints d’une MII au Canada.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Un sondage de 29 questions a été élaboré au moyen d’un outil virtuel de création de sondages (www.surveymonkey.com), afin d’explorer la démographie des soins infirmiers, les rôles des infirmières à l’égard des MII et les services de soins infirmiers prodigués au Canada. Ce sondage, qui est demeuré en ligne 15 semaines, a été distribué à la Société canadienne des infirmières et infirmiers en gastroentérologie et travailleurs associés, à l’Association canadienne de gastroentérologie et aux coordon-nateurs de Progress (AbbVie Corporation, États-Unis) et BioAdvance (Janssen Inc, États-Unis) (par courriel).

RÉSULTATS :

Sur les 275 répondants au sondage, 98,2 % étaient des infirmières (et non des infirmiers), et 68,7 % avaient un emploi à temps plein. De ce nombre, 42,5 % avaient de 51 à 60 ans, et 32,4 %, de 41 à 50 ans. De plus, 53,8 % possédaient un diplôme en soins infirmiers, 35,3 %, un bac-calauréat en soins infirmiers et 4,4%, une maîtrise en soins infirmiers. Près de la moitié (44 % [n=121]) occupait un emploi en Ontario, suivie de 19,6 % (n=54) en Alberta et de 9,1 % (n=25) en Colombie-Britannique. Toutes les provinces étaient représentées, à l’exception du Nunavut et des Territoires du Nord-Ouest. Quarante-trois pour cent des infirmières (n=119) ont précisé travailler dans une unité d’endoscopie. Des 90 % qui ont affirmé travailler avec des patients atteints d’une MII, seulement 30 % (n=79) jouaient un rôle primaire en soins des MII. Chez les 79 infirmières ayant un rôle primaire en soins des MII, 79,7 % travaillaient auprès de la population adulte, 10,1 % auprès de la population d’âge pédiatrique et 10,1 % auprès des patients adultes et d’âge pédiatrique. Elles travaillaient surtout en consultations externes (67,1 %).

CONCLUSIONS :

Les résultats du sondage ont démontré que seul un petit pourcentage d’infirmières canadiennes en gastroentérologie donne des soins cliniques des MII. Bon nombre ont des rôles et responsabilités multiples et offrent des services variés. On n’a pu établir clairement l’ampleur exacte de leurs soins et de leurs services. D’autres études s’imposent.

Managing patients living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) requires a multidisciplinary approach using the expertise of physicians, nurses, dieticians, social workers and psychologists.

The literature has reported the emergence of the ‘nurse specialist’ in IBD and the significant contribution nurses play in the management of IBD (1). Not only do nurses provide patients with education, counselling and support, but with the evolving roles of advanced practice nurses (APNs), investigating, diagnosing, prescribing and/or monitoring therapy is also within their scopes of practice.

IBD is a chronic disease and includes both Crohn disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). IBD is a chronic relapsing condition that can negatively impact quality of life and contribute significant cost to the health care system (2). Disease activity often fluctuates over time and, therefore, requires maintenance therapy and acute interventions to target disease flares. The medical model of care is often reactive (3). Currently there is no preventive treatment for IBD and comprehensive management is required. Disease management aims to maximize time in remission, alleviate or reduce symptoms, resolve complications and improve quality of life.

The Canadian Nurses Association emphasizes the patients’ central role in the management of their illness (4). Patient education surrounding the disease process and medications helps patients achieve the best possible quality of life with their chronic conditions. Registered nurses (RNs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) play an integral role in chronic disease management.

Nursing is a self-regulated profession, and through provincial and territorial legislation, nursing regulatory bodies are accountable for the protection of the public (5). In Canada, there are three nursing roles – registered practical nurse/licensed practical nurse (RPN/LPN), RN and APN. APNs include both NPs and clinical nurse specialists. An RPN/LPN obtains a two-year diploma in practical nursing through a community college, whereas an RN completes a four-year Bachelor’s degree in nursing. Both RPN/LPNs and RNs write a certification examination. In practice, an RPN/LPN manages stable patients and is able to assist with health education and medication management. An RN manages both acute and chronic patients, can perform physical examinations, provides patient education and is able to monitor medical therapy. The clinical nurse specialist is a registered nurse who holds a Master’s or Doctoral degree in nursing. They have advanced knowledge and clinical expertise in a nursing specialty (6). The NP has additional experience/training with a Masters in nursing degree and can autonomously diagnose, order and interpret diagnostic tests; prescribe pharmaceuticals; and perform procedures within their legislated scope of practice.

Nightingale et al (7) studied the effects of IBD nurse specialists on outcomes in patients with IBD. Patients were provided with educational materials on lifestyle, health promotion, medications and diagnostic tests. Patients also had telephone access to the specialist nurse. IBD nurses provided improved patient education, satisfaction and disease management. Patient satisfaction improved with access to information on IBD. The study reported a 38% decrease in hospital visits and a 19% decrease in the length of hospital stays. The authors concluded that IBD nurse specialists were valuable and cost-effective members of the team.

In 2010, Hernandez-Sampelayo et al (8) reviewed the scientific evidence regarding the quality of care in IBD patients in relation to nurses. The review highlighted the importance of having IBD specialist nurses and indicated that patients with access to this service were reported to experience beneficial outcomes. The authors identified methodological limitations of the studies reviewed and suggested further research – specifically in nursing interventions and patient outcomes.

In 2011, The Royal College of Nursing in the United Kingdom (UK) published findings from its national IBD nursing audit (9). The goals of the audit were to: evaluate the IBD nursing services and identify areas for improvement; provide national evidence of IBD nurse numbers, activity and effectiveness; and provide feedback to nurses demonstrating the impact of IBD nursing service. This audit provided national data supporting the important contribution IBD nurses make to patients living with IBD in the UK.

Furthermore, in May 2011, 240 IBD nurses from across the UK were invited to complete an online survey related to their professional background, service and daily activity. The results identified several important factors regarding the IBD nursing profile, service profile and activity, namely, job specifics, nursing education, nonmedical prescribing, managerial responsibilities, clinical responsibilities, workplace environment, nursing educational activities and patient education materials.

The survey revealed that the number of IBD nurses across the UK is increasing. The majority of IBD nurses also had other gastroenterology (GI)-related roles and only a percentage of their patient load was committed to IBD patients. Many similarities within their roles were identified such as emergency telephone contact and advice, patient information, counselling, monitoring and administration of IBD therapy. Much of the IBD nurse specialist activity was centred in acute hospital settings, and they were often the link between primary and secondary care.

As reported in previous research (7,8), the management of IBD is a complex process and nursing plays an invaluable and necessary role in the treatment and care of individuals with IBD. The UK audit emphasized several important points that are critical for the successful treatment of IBD – namely, the number of nurses, activities and services in which they participate. Unlike the valuable information that was obtained in the UK, Canadian nursing support, roles in IBD care and management is poorly understood and documented. Canada has among the highest reported prevalence and incidence of IBD in the world. As highlighted in the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada report The Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada 2012 (10), there are approximately 233,000 Canadians living with IBD (129,000 with CD and 104,000 with UC). The report also suggested that >10,200 new cases of IBD are diagnosed every year. Given the staggering numbers of people living with IBD, one hopes that there are sufficient numbers of nurses specialized in this field to consistently provide ongoing care and disease-management support. Unfortunately, this may not be the case.

Recognizing the documentation of the valuable work performed in the UK, it was decided that the role of the nurse specialist in IBD should be evaluated in Canada. The authors developed a Canadian IBD Nurses Survey with the purpose of conducting a geographical assessment of GI nurses working with IBD patients in Canada. The goals were to gain an understanding of the community of nurses impacting the care of IBD patients and garner an appreciation of the demographics of IBD nurses including age, sex, years of experience, educational preparation, employment setting and scope of practice. With the results of this survey, the authors would determine whether there was interest among those surveyed in establishing a Canadian IBD Nurses Interest Group.

METHODS

The Canadian Inflammatory Bowel Disease Nurse’s Survey was developed by the authors and was targeted at GI nurses (RPN/LPNs, RNs and APNs) who had a role in caring for patients with IBD. The 29-question survey was developed using an Internet-based survey tool (www.surveymonkey.com), to assess nursing demographics, the role of the IBD nurse and nursing services provided across Canada.

In October 2012, the survey was distributed through Survey Monkey to GI nurses across the country. In collaboration with the Canadian Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates (CSGNA) and the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG), the survey was circulated to their memberships via e-mail. The survey was e-mailed to 395 CSGNA members and 439 CAG clinical members. The authors believed it was important to include the large number of nurses in the community that work with IBD patients. The survey was also distributed to nurses working within the ‘Progress’ (AbbVie Corporation, USA [n=47]) and ‘BioAdvance’ (Janssen Inc, USA [n=75]) patient support programs. The Progress and BioAdvance programs offer support and care to patients receiving biologic therapy. The authors invited known IBD nurse specialists from across the country to assist in disseminating the survey to GI nurses. The authors also connected with nursing colleagues from past nursing conferences, nursing advisory board meetings and research investigator meetings.

The survey was administered online and remained open for an extended period of time to ensure and encourage participation, particularly from those in the patient-support programs. It concluded at the end of January 2013.

The study cohort was characterized using standard descriptive statistics. χ2 tests were used to determine the association between job titles and the categorical variables. For continuous variables, ANOVA was used to test for differences among the nursing groups. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS statistical software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, USA). All tests were two-tailed and P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographics

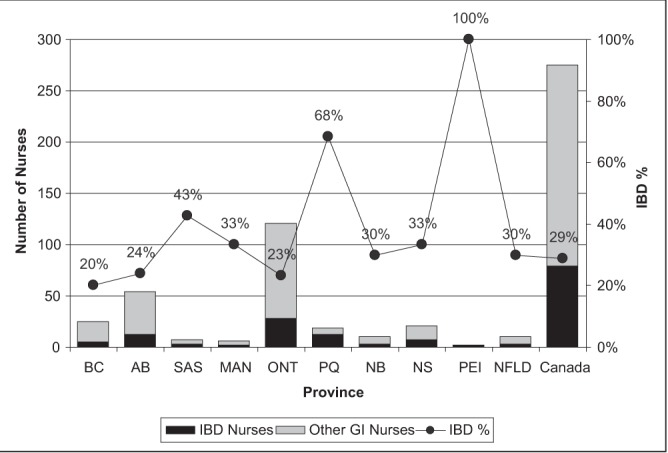

The survey generated feedback from 275 nurses. Of those surveyed, with the exception of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, 44% (n=121) of nurses were employed in Ontario, followed by 19.6% (n=54) in Alberta and 9.1% (n=25) in British Columbia (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Geographical distribution of the respondents and their role in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). AB Alberta; BC British Columbia; GI Gastroenterology; MAN Manitoba; NB New Brunswick; NFLD Newfoundland and Labrador; NS Nova Scotia; ONT Ontario; PEI Prince Edward Island; PQ Quebec; SAS Saskatchewan

Of the 275 respondents, 98.2% were female; among them, 68.7% were employed in full-time positions and the remainder in part-time positions. Of the part-time nurses surveyed, 19.8% worked <35 h per week and, of these, 8.3% worked <20 h per week. Two per cent of nurses were working ‘casual’ hours or <10 h per week. Of the nurses surveyed, 53.8% were diploma-prepared RNs, 35.3% were Baccalaureate-prepared nurses and 4.4% were Masters-prepared nurses.

Overall, 5.8% of nurses surveyed were between 21 and 30 years of age; 13.1% were between 31 and 40; 32.4% were between 41 and 50; 42.5% were between 51 and 60; and 6.2% were between 61 and 70. Slightly more than 63% of the nurses surveyed had >25 years of nursing experience.

Nursing role and geographical variation

Of the 275 GI nurses surveyed, 90% reported that they worked with IBD patients; however, only 79 (28.7%) indicated that their primary nursing role was in IBD care (Figure 1). The proportion of primary nursing role in IBD care showed significant variation across the provinces (from 20% to 100%; P=0.0045). The job titles of nurses also showed a significant variation among the provinces (P<0.0001) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Job titles of gastroenterology nurses according to province

| Job title | Canada (n=275) | BC (n=25) | AB (n=54) | SAS (n=7) | MAN (n=6) | ONT (n=121) | PQ (n=19) | NB (n=10) | NS (n=21) | PEI (n=2) | NFLD (n=10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced practice nurse | 12 (4.4) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (5.8) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nurse clinician | 24 (8.7) | 4 (16.0) | 5 (9.3) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.3) | 10 (52.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Staff nurse | 145 (52.7) | 18 (72.0) | 29 (53.7) | 5 (71.4) | 2 (33.3) | 67 (55.4) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (30.0) | 11 (52.4) | 1 (50.0) | 7 (70.0) |

| Research coordinator | 15 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (33.3) | 8 (6.6) | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| LPN/RPN | 5 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| BioAdvance*/Progress† coordinator | 32 (11.6) | 1 (4.0) | 6 (11.1) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (14.0) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 42 (15.3) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (33.3) | 18 (14.9) | 2 (10.5) | 6 (60.0) | 4 (19.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (30.0) |

Data presented as n (%).

Janssen Inc, USA;

AbbVie Corporation, USA. AB Alberta; BC British Columbia; LPN Licenced practical nurse; MAN Manitoba; NB New Brunswick; NFLD Newfoundland and Labrador; NS Nova Scotia; ONT Ontario; PEI Prince Edward Island; PQ Quebec; RPN Registered practical nurse; SAS Saskatchewan

IBD nursing services

A total of 118 nurses were identified as working in endoscopy units. Although this group is essential to nursing care for those with IBD, their roles are well defined and understood within the nursing community; therefore, their responses were removed from this analysis. Of the 79 respondents with a clinical focus in IBD nursing care, results showed that 31.6% worked in inpatient care whereas 67.1% provided outpatient services (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Nursing services provided by those who indicated inflammatory bowel disease care was their primary nursing role

| Nursing service | Overall (n=79) | Advanced practice nurse (n=5) | Nurse clinician (n=13) | Staff nurse (n=18) | Research coordinator (n=13) | BioAdvance*/Progress† coordinator (n=19) | Other (n=11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient care | 25 (31.6) | 2 (40.0) | 8 (61.5) | 6 (33.3) | 4 (30.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (45.5) |

| Outpatient care | 53 (67.1) | 5 (100.0) | 13 (100.0) | 15 (83.3) | 10 (76.9) | 4 (21.1) | 6 (54.5) |

| Telephone advice line | 31 (39.2) | 4 (80.0) | 13 (100.0) | 4 (22.2) | 2 (15.4) | 4 (21.1) | 4 (36.4) |

| Rapid access clinic | 19 (24.1) | 4 (80.0) | 6 (46.2) | 3 (16.7) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (18.2) |

| Transitional care service | 19 (24.1) | 4 (80.0) | 5 (38.5) | 4 (22.2) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (27.3) |

| Management of biological service | 44 (55.7) | 2 (40.0) | 4 (30.8) | 8 (44.4) | 3 (23.1) | 19 (100.0) | 8 (72.7) |

Data presented as n (%).

Janssen Inc, USA;

AbbVie Corporation, USA

Further analysis of nurses who worked primarily in IBD care showed that 79.7% worked with the adult population, 10.1% worked with the pediatric population and 10.1% worked with both adult and pediatric patients with IBD.

Staff RNs and nurse clinicians represented 39% of the IBD nurses identified (Table 2). Of these, 45% provided inpatient care and 90% provided outpatient care. In the outpatient setting, RNs/nurse clinicians provided the largest overall service to IBD patients – most of which was within the telephone advice, rapid access and transition services.

IBD research nurses/coordinators represented 16.5% of respondents. The majority of research coordinators worked predominantly in outpatient settings (76.9%, Table 2). In addition to providing clinical care, research nurses are responsible for coordinating clinical research, ensuring participant safety, confirming accuracy of data collection, recording, ongoing maintenance of informed consent and guaranteeing the overall integrity of protocol implementation (11).

The ‘other’ respondents (13.9%) reported having various titles such as Clinic coordinator, Nurse manager, Endoscopy nurse, Research assistant, Director of clinic services, Nurse endoscopist, Nurse-performed flexible sigmoidoscopy coordinator, Research nurse, Field case manager, Clinical leader and Case manager/coordinator. Almost three-quarters (72.7%) of this group provided biologic services followed by telephone advice (36.4%), rapid access clinic (18.2%) and transition services (27.3%).

All services, including inpatient, outpatient, telephone advice line, rapid access clinics, transition and biologic, are offered within the nursing population but to varying degrees. In assessing the average nursing time devoted to individual services (Table 3), findings showed that most IBD nurses devoted their clinical time to the outpatient setting (39.3%), whereas inpatient care represented only 8.6% of their duties. Nurse clinicians devoted almost one-half of their time (43.9%) to providing telephone advice whereas the remainder of the group devoted just <15%.

TABLE 3.

Average time devoted to services

| Nursing service | Overall (n=79) | Advanced practice nurse (n=5) | Nurse clinician (n=13) | Staff nurse (n=18) | Research coordinator (n=13) | BioAdvance*/Progress† coordinator (n=19) | Other (n=11) | P‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient care | 8.6 | 10.0 | 3.5 | 15.9 | 10.4 | 0.0 | 15.0 | 0.1624 |

| Outpatient care | 39.3 | 58.0 | 41.5 | 54.6 | 63.9 | 12.8 | 21.4 | 0.0001 |

| Telephone advice line | 15.7 | 14.0 | 43.9 | 11.2 | 3.2 | 10.6 | 12.3 | <0.0001 |

| Rapid access clinic | 4.3 | 10.0 | 12.7 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 0.1244 |

| Transitional care service | 3.6 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 0.8766 |

| Management of biological service | 30.1 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 21.2 | 4.2 | 71.9 | 45.5 | <0.0001 |

Data presented as % unless otherwise indicated.

Janssen Inc, USA;

AbbVie Corporation, USA;

ANOVA test

DISCUSSION

The overall response rate for the present survey exceeded the authors’ expectations by reaching 275 GI nurses across Canada. Results indicated that almost one-half of the nurses were >50 years of age, with 63.6% having >20 years of nursing experience. The majority of respondents (92.7%) worked with IBD patients, yet only 28.7% described IBD as their primary role. The majority of IBD nurses worked with adults in the outpatient setting but services including inpatient care, telephone advice line, rapid access clinics, transition and biologic were offered. The exact depth of care and service provided is unclear and requires further investigation. There was variation among job titles in those surveyed. Variability existed even among similar roles such as in research nurse/research coordinator. The survey results also revealed that many respondents have multiple roles and responsibilities including managerial, nurse endoscopist, reimbursement specialist, infusion clinic coordinator, endoscopy nurse and enterostomal therapist. Along with GI nursing, some nurses also worked outside of GI in cardiology, internal medicine, oncology, dermatology and nephrology. They also treated patients with gastrointestinal illnesses other than IBD including hepatology, colorectal cancer screening and management, celiac disease and gastroesophagel reflux disease.

IBD is a chronic condition and resources are needed for high-quality management. The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada report identified several challenges facing the IBD community (10). Social awareness of IBD, access to IBD specialists and timely access for consultation, diagnosis, treatment and therapy were discussed in the 2012 Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada report (10). The report found that both new and long-standing IBD patients endure long wait times for consultation, investigations and therapy. In addition, there exists a decline in the number of gastroenterologists in Canada with a greater number of specialists approaching retirement. This concern also impacts nursing in Canada, with current pressures on the nursing workforce that include increased workloads, shortage in full-time nursing positions and, as the present study shows, an aging nursing population close to retirement. These data support the concern that the average age of nurses in Canada is increasing and it is critical to consider a succession plan.

Historically, nurses have been an important part of the multidisciplinary approach to IBD management. Nurses have been shown to provide consistent, high-quality care, improve continuity in patient care and act as the liaison between specialists, primary care providers and those within the multidisciplinary team. Nurses are relied on to provide patient education, counselling, and physical and emotional support.

A challenge for IBD nurses in Canada is to provide evidence supporting the relevance of their role in caring for IBD patients. The degree to which nurses impact IBD-specific patient outcomes requires further exploration. Nurses are in a unique position to measure hospital admission rates, emergency department visits, surgical rates, complication rates, medication compliance and patient quality of life. Although this is important for patient care, it will also contribute to the validation of nursing roles in IBD management and for estimates of health human resource requirements.

With the existing challenges facing IBD patients and their health care providers, the concept of ‘nurse-led’ IBD clinics needs to be explored and documented in greater detail. IBD nurse specialists, in collaboration with their IBD physician counterpart, could reduce wait times for consultation, diagnosis and initiation of therapy. Unlike in the UK, services such as telephone helplines, outpatient clinics, biologic and immunosuppression services, rapid access clinic and transitional care services are not widely available throughout Canada. With ongoing growth and expansion of the nurse specialist role in IBD in Canada, further development of these services could be possible. With additional investment in IBD nursing resources, the potential for shorter wait times, reductions in emergency department visits, decreased length of inpatient stay, increased patient quality of life and decreased complication rates may also be achievable. This approach has been implemented and is effective in many other disease states such as diabetes and hypertension (10). Although the aim of many nursing initiatives is to improve patient outcomes, there is limited quality research on the extent of nursing’s influence on IBD health outcomes.

The survey also provided each respondent with an opportunity to provide comments regarding the questionnaire and their professional needs. Many nurses suggested that additional support and mentoring is needed for novice IBD nurses in Canada. Further development and expansion of IBD nursing roles was addressed, along with the need for learning opportunities and networking with other nurses. There was interest expressed in developing a national IBD Nurses Interest Group as a forum to address these needs.

The present survey provided insight into the numbers of Canadian nurses impacting the care of IBD patients, and the demographics of IBD nurses including age, sex, years of nursing experience, educational preparation, employment setting and scope of practice. As a result of this exercise, several additional questions have been identified. Further exploration into specific nursing services in Canada, educational preparation, scope of nursing practice, nursing responsibilities and the educational needs of IBD nurses in Canada is still required.

Limitations to the present study were identified. The response rate was not calculated because distribution numbers were unclear. The survey was distributed through several organizations. The authors reached out to nurses through gastroenterologists and members of the CAG, CSGNA, BioAdvance and Progress. The authors relied on these individuals to distribute the survey to nurses who may not have been part of the initial distribution group. There is a possibility that relevant nurses were missed and did not receive the survey. In addition, the survey used was not validated. It was presented in English and was not available in French for Quebec colleagues. There appeared to be confusion regarding job title description in some of the surveys submitted. Definitions of ‘Nurse clinician’ and ‘Staff nurse’ (endoscopy, ward, outpatient clinic, community physician offices) may have been helpful for respondents. Definitions regarding services, such as ‘transition’ and ‘biologic’, may have been helpful to those who may not be familiar with these programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Jiming Fang, biostatistical consultant in Toronto, Ontario, who provided statistical assistance and suggestions for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marin L, Torrejon A, Oltra L, et al. Nursing resources and responsibilities according to hospital organizational model for management of inflammatory bowel disease in Spain. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Randell RL, Long MD, Martin CF, et al. Patient perception of chronic illness care in a large inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1428–33. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182813434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sack C, Phan VA, Grafton R, et al. A chronic care model significantly decreases costs and healthcare utilisation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:302–10. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Nurses Association . Effectiveness of Registered Nurses and Nurse Practitioners in Supporting Chronic Disease Self-Management March 2012. Ottawa: Canadian Nurses Association; [Google Scholar]

- 5.College of Nurses of Ontario . Practice Standard: Professional Standards, Revised June 2009. Toronto: College of Nurses of Ontario; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamric AB, Spross JA. The Clinical Nurse Specialist in Theory and Practice. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1989. p. 466. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nightingale AJ, Middleton W, Middleton SJ, Hunter JO. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a specialist nurse in the management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:967–73. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez-Sampelayo P, Seoane M, Oltra L, et al. Contribution of nurses to the quality of care in management of inflammatory bowel disease: A synthesis of the evidence. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:611–22. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mason I, Holbrook K, Kemp K, Garrick V, Johns K, Kane M. Inflammatory bowel disease nursing: Results of an audit exploring the roles, responsibilities and activity of nurses with specialist/advanced roles. London: Royal College of Nursing; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada . Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada 2012. Toronto: Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada; [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hastings C. Clinical Research Nursing. < http://clinicalcenter.nih.gov/nursing/crn/crn_2010.html> 2010(Accessed August 15, 2013). [Google Scholar]