Abstract

An earlier report identified higher risks of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in White children compared with the Japanese after HLA-matched sibling transplantations. The current analysis explored whether racial differences are associated with GVHD risks after unrelated umbilical cord blood transplantation. Included are patients of Japanese descent (n = 257) and Whites (n = 260; 168 of 260 received antithymocyte globulin [ATG]). Transplants were performed in the United States or Japan between 2000 and 2009; patients were aged 16 years or younger, had acute leukemia, were in complete remission, and received a myeloablative conditioning regimen. The median ages of the Japanese and Whites who received ATG were younger at 5 years compared with 8 years for Whites who did not receive ATG. In all groups most transplants were mismatched at 1 or 2 HLA loci. Multivariate analysis found no differences in risks of acute GVHD between the Japanese and Whites. However, chronic GVHD was higher in Whites who did not receive ATG compared with the Japanese (hazard ratio, 2.16; P < .001), and treatment-related mortality was higher in Whites who received ATG compared with the Japanese (relative risk, 1.81; P = .01). Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in overall survival between the 3 groups.

Keywords: GVHD, Umbilical cord blood, transplantation

Introduction

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [1]. Acute GVHD risks are higher after HLA-mismatched compared with HLA-matched transplantations and primarily attributed to mismatching at major histocompatibility antigens. On the other hand, donor–recipient mismatching for minor histocompatibility antigens may explain GVHD after HLA-matched transplantations. In an earlier report, Oh et al. [2] compared GVHD and overall survival between different ethnic populations after HLA-matched related bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies. That report, which included children and adults, showed higher acute but not chronic GVHD risks for adult U.S. Whites compared with adults of Japanese descent. However, among children, both acute and chronic GVHD risks were higher in U.S. Whites compared with the Japanese. In that report, the observed differences between the Japanese and Whites were attributed to the relative homogeneity of minor histocompatibility antigens in persons of Japanese descent [3].

Umbilical cord blood (UCB) is less immunogenic, and consequently HLA mismatches that are prohibitive between unrelated adult donors and recipients are considered acceptable up to 2 mismatches when selecting UCB units. The practice of transplanting UCB units (UCBT) that are HLA mismatched to recipients is common in both children and adults worldwide [4-8]. To our knowledge, no published reports explore whether racial differences exist in acute and chronic GVHD risks after UCBT. Almost all UCB units used in Japan are from cord blood banks in Japan, allowing for a homogeneous cohort of donors. On the other hand, the U.S. population is genetically diverse, and UCB units may have been obtained through either a U.S. or international cord blood bank. Additionally, differences in transplantation strategies exist. In Japan, UCB units generally contain fewer total nucleated cells (TNCs) than in the United States and consider lower resolution HLA match (antigen level) at HLA-A, -B, and -DR. In the United States, HLA matching at the DR locus considers allele-level match. Additionally, antithymocyte globulin (ATG) was routinely included in the transplant preparatory regimen before 2007 in the United States [8,9]. Another key difference between the 2 countries is the co-infusion of 2 UCB units, routine in the United States, for adults. Consequently, the current analysis is limited to younger patients such that the comparison is between appropriately aged patients who were transplanted with a single UCB unit. In this report we compare acute and chronic GVHD and mortality risks after UCBT between Japanese and White children with acute leukemia to test whether the genetic diversity of donors and recipients influenced the likelihood of GVHD.

Methods

Data Source

Data were obtained from the right for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research [10] for U.S. transplants and from the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (JSHCT) and the Japan Cord Blood Bank Network [11] for Japanese transplants. All U.S. patients provided consent for research participation. Patient consent is not required for registration of the JSHCT because registry data consist of anonymized clinical information. The institutional review board of the National Marrow Donor Program, Medical College of Wisconsin, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, and the Data Management Committees of the JSHCT and the Japan Cord Blood Bank Network approved this study.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients were 16 years old and younger with acute myeloid leukemia or acute lymphoblastic leukemia and in first, second, or third complete remission (CR). All patients received a myeloablative transplant conditioning regimen and were transplanted in Japan or the United States between 2000 and 2009. Excluded were non-Whites transplanted in the United States, transplantations in relapse, prior allogeneic transplantation, infusion of 2 UCB units, or reduced-intensity transplant conditioning regimens. Five hundred seventeen patients were eligible: 257 transplants from Japan, 168 transplants for Whites that included ATG in their transplant regimen, and 92 transplants for Whites without ATG. Units were matched to patients at the antigen level at HLA-A and -B and at the allele level at HLA-DRB1; for the Japanese cohort, this occurred retrospectively.

Outcomes

Acute and chronic GVHD were defined as time to occurrence of GVHD, using standard criteria [12,13]. Treatment-related mortality (TRM) was defined as death without leukemia relapse. Relapse was defined as hematological/morphological recurrence of leukemia. Overall mortality was defined as death from any cause.

Statistical Analysis

To compare the outcomes of interest, Cox proportional hazards models were used to adjust for potential imbalance in baseline characteristics between the 3 treatment groups [14,15]. The main effect term, Japanese versus Whites who received ATG versus Whites who did not receive ATG, was held in all steps of model building regardless of level of significance. Other variables considered were age at transplantation (≤5 versus 6 to 16 years), gender, recipient cytomegalovirus (CMV) serostatus, disease, disease status, TNCs (≤3 versus >3 × 107/kg), HLA match (6/6 versus 5/6 versus 4/6), transplant preparative regimen (containing total body irradiation [TBI] versus not), GVHD prophylaxis (containing cyclosporine versus tacrolimus), and period (2000 to 2006 versus 2007 to 2009). All variables met the proportionality assumption, and there were no first-order interactions between variables in the final model and the main effect term. The effects of acute and chronic GVHD were also tested for their effect on overall mortality as time-dependent covariates. Results are expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) together with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Adjusted cumulative incidences of acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, relapse, and TRM [16] and adjusted probabilities of survival [17] were calculated using the multivariate models, stratified on the 3 treatment groups, and weighted by the pooled sample proportion value for each prognostic factor. SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC) was used in the analyses.

Results

Table 1 shows characteristics of patients, their diseases, and transplant regimens by the 3 treatment groups: Japanese, Whites who received ATG, and Whites who did not receive ATG. None of the Japanese patients received ATG. The median ages of the Japanese and Whites who received ATG was 5 years, whereas Whites who did not receive ATG were slightly older at 8 years.

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Patients.

| Japanese (n = 257) | White, with ATG (n = 168) | White, no ATG (n = 92) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant, yr | <.0001 | |||

| ≤5 | 135 (53%) | 85 (51%) | 25 (27%) | |

| 6-16 | 122 (47%) | 83 (49%) | 67 (73%) | |

| Gender | .73 | |||

| Female | 116 (45%) | 81 (48%) | 40 (43%) | |

| Male | 141 (55%) | 87 (52%) | 52 (57%) | |

| Recipient CMV status | <.0001 | |||

| Negative | 78 (30%) | 88 (52%) | 43 (47%) | |

| Positive | 115 (45%) | 80 (48%) | 48 (52%) | |

| Unknown | 64 (25%) | — | 1 (1%) | |

| Disease | <.0001 | |||

| AML | 70 (27%) | 88 (52%) | 23 (25%) | |

| ALL | 187 (73%) | 80 (48%) | 69 (75%) | |

| Disease risk | <.0001 | |||

| CR1 | 156 (61%) | 61 (36%) | 32 (35%) | |

| CR2/CR3 | 101 (39%) | 107 (64%) | 60 (65%) | |

| Year of transplant | <.0001 | |||

| 2000-2006 | 174 (68%) | 105 (63%) | 27 (29%) | |

| 2007-2009 | 83 (32%) | 63 (38%) | 65 (71%) | |

| No. of cryopreserved TNCs × 107/kg | <.0001 | |||

| <3 | 48 (19%) | 4 (2%) | 9 (10%) | |

| ≥3 | 201 (78%) | 164 (98%) | 83 (90%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (3%) | — | — | |

| HLA match status (A B; intermediate resolution, DRB1; allele level) | .51 | |||

| 6/6 | 47 (18%) | 42 (25%) | 17 (18%) | |

| 5/6 | 127 (49%) | 75 (45%) | 47 (51%) | |

| 4/6 | 83 (32%) | 51 (30%) | 28 (30%) | |

| Conditioning regimen | <.0001 | |||

| Non-TBI | 75 (29%) | 74 (44%) | 8 (9%) | |

| TBI | 182 (71%) | 94 (56%) | 84 (91%) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | <.0001 | |||

| Cyclosporine containing | 122 (47%) | 138 (82%) | 54 (59%) | |

| Tacrolimus containing | 135 (53%) | 30 (18%) | 38 (41%) | |

| Median follow-up of survivors, mo (range) | <.0001 | |||

| 61 (10-138) | 52 (12-123) | 36 (13-85) |

CMV indicates cytomegalovirus; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

There were other differences: Japanese patients were more likely to be CMV seropositive, to be transplanted in first CR, and more likely to receive a UCB unit with TNCs < 3 × 107/kg compared with Whites. Median TNC doses were 5.1 × 107/kg (range, 1.3 to 48), 7.4 × 107/kg (range, 1.6 to 50), and 5.7 × 107/kg (range, 1.6 to 21) for Japanese, Whites who received ATG, and Whites who did not receive ATG, respectively. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia was the predominant indication for the Japanese and Whites after 2006.

Differences were found in GVHD prophylaxis. About half of the Japanese patients received tacrolimus-containing GVHD prophylaxis, whereas most Whites used cyclosporine-containing GVHD prophylaxis. There were no significant differences in degree of donor–recipient HLA match by race; about half of all transplants were mismatched at a single HLA locus and about a third were mismatched at 2 HLA loci. The median follow-up for Whites who did not receive ATG was 3 years compared with 4 years Whites who received ATG and 5 years for the Japanese.

Acute and Chronic GVHD

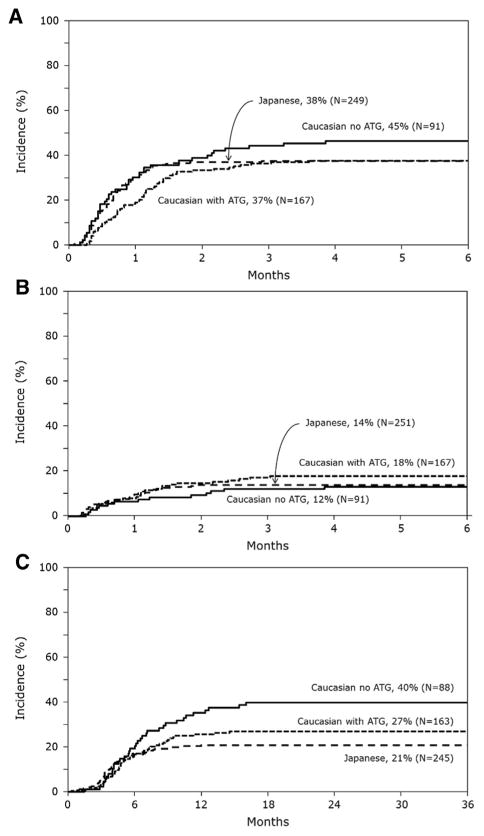

There were no significant differences in the risks of grades II to IV and grades III to IV acute GVHD among the 3 groups (Table 2). No other factors were associated with grades II to IV acute GVHD, but grades III to IV acute GVHD risks were higher for patients aged 6 to 16 years compared with younger patients (HR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.19 to 3.14; P =.008) and boys (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.07 to 2.75; P = .03). The 100-day adjusted cumulative incidences of grades II to IV acute GVHD were 38% (95% CI, 32% to 43%), 37% (95% CI, 30% to 44%), and 45% (95% CI, 35% to 55%) for the Japanese, Whites who received ATG, and Whites who did not receive ATG, respectively (Figure 1A). The corresponding probabilities for grades III to IV acute GVHD were 14% (95% CI,10% to 19%), 18% (95% CI, 13% to 24%), and 12% (95% CI, 7% to 19%, Figure 1B).

Table 2. Multivariate Analysis of Acute and Chronic GVHD, TRM, Relapse, and Overall Mortality.

| Number | HR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grades II-IV acute GVHD | |||

| Japanese | 249 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Whites, received ATG | 167 | .93 (.68-1.28) | .64 |

| Whites, did not receive ATG | 91 | 1.27 (.88-1.82) | .20 |

| Grades III-IV acute GVHD | |||

| Japanese | 251 | 1.00 | Reference |

| White, with ATG | 167 | 1.34 (.82-2.18) | .25 |

| White, no ATG | 91 | .93 (.50-1.75) | .83 |

| Chronic GVHD | |||

| Japanese | 245 | 1.00 | Reference |

| White, with ATG | 163 | 1.43 (.96-2.14) | .08 |

| White, no ATG | 88 | 2.16 (1.40-3.32) | <.001 |

| TRM | |||

| Japanese | 242 | 1.00 | Reference |

| White, with ATG | 167 | 1.81 (1.16-2.83) | .01 |

| White, no ATG | 91 | 1.28 (.74-2.22) | .39 |

| Relapse | |||

| Japanese | 242 | 1.00 | Reference |

| White, with ATG | 167 | .92 (.62-1.35) | .66 |

| White, no ATG | 91 | .77 (.47-1.28) | .32 |

| Overall mortality* | |||

| Japanese | 253 | 1.00 | Reference |

| White, with ATG | 167 | 1.40 (1.00-1.94) | .05 |

| White, no ATG | 91 | 1.17 (.78-1.76) | .45 |

Two degrees of freedom overall test for overall mortality showed no statistical significance (P = .14).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of GVHD after single-unit UCBT. (A) Cumulative incidences of grades II to IV acute GVHD. (B) Cumulative incidences of grades III to IV acute GVHD. (C) Cumulative incidences of chronic GVHD.

Chronic GVHD risks differed by transplant strategy. Compared with the Japanese, risks were significantly higher in Whites who did not receive ATG (HR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.40 to 3.32; P < .001) than for Whites who received ATG (Table 2). There were no differences in the severity of chronic GVHD; among those with chronic GVHD, the proportion of patients with extensive chronic GVHD was 33% for the Japanese, 48% for Whites receiving ATG, and 44% for Whites who did not receive ATG (P = .28). The 3-year cumulative incidences of chronic GVHD were 21% (95% CI,16% to 26%) for the Japanese, 27% (95% CI, 20% to 34%) for Whites who received ATG, and 40% (95% CI, 30% to 50%) for Whites who did not receive ATG (Figure 1C).

TRM and Relapse

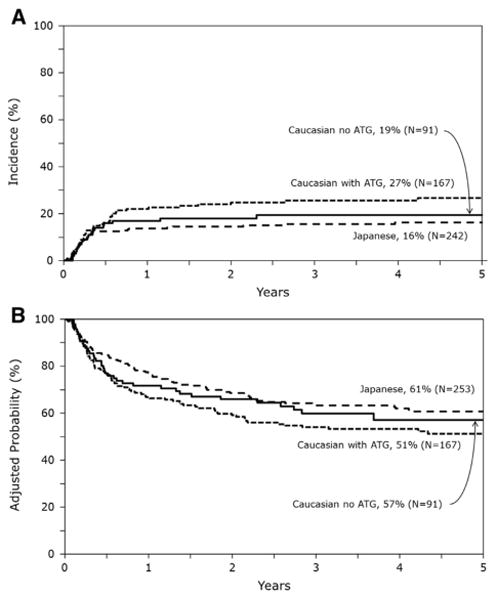

Compared with the Japanese, risks of TRM were significantly higher for Whites who received ATG but not for Whites who did not receive ATG (Table 2). Independent of geographical region and use of ATG, transplantations mismatched at 2 HLA loci (HR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.14 to 4.12; P =.02) were associated with higher TRM compared with HLA-matched transplantations. TBI-containing regimens were also associated with higher TRM compared with non-TBI regimens (HR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.32 to 3.89; P = .003). The 3-year cumulative incidence of TRM was 15% (95% CI, 11% to 20%) for the Japanese, 26% (95% CI, 19% to 33%) for Whites who received ATG, and 19% (95% CI, 12% to 28%) for Whites who did not receive ATG (Figure 2A). Relapse risks were not different among the 3 groups (Table 2). Relapse was associated with disease status at transplantation; transplants in second or third CR were associated with higher risks compared with first CR (HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.12 to 2.30; P =.01).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of TRM and overall survival curves. (A) Cumulative incidences of TRM. (B) Probability of overall survival after single-unit UCBT adjusted for CMV-seropositive status and disease risk at transplantation.

The 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse was 28% (95% CI, 23% to 34%) for the Japanese, 26% (95% CI, 20% to 33%) for Whites who received ATG, and 22% (95% CI, 14% to 31%) for Whites who did not receive ATG.

Overall Mortality

After adjusting for CMV serostatus and disease status at transplantation, factors associated with overall mortality, there were no differences in mortality risks between the Japanese and Whites who did not receive ATG (Table 2). However, the observed marginal increase in overall mortality risk for Whites who received ATG compared with the Japanese must be interpreted with caution. The level of significance for the overall mortality model did not reach the level of significance set for this analysis (P = .14; 2 degrees of freedom test). Consequently, any observed differences between exposure categories within the model are suspect and call for confirmation in an independent data set. Independent of region, mortality risks were higher for patients who were CMV seropositive (HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.16 to 2.11; P = .003) and for transplantations in second or third CR (HR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.15 to 2.06; P = .003).

We also tested for the effect of acute (grades II to IV: HR, 1.19; 95% CI, .90 to 1.57; P =.23, grades III to IV: HR, 1.38; 95% CI, .96 to 1.98; P = .08) and chronic GVHD (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, .78 to 1.65; P = .5) on overall mortality and found none. The 3-year probabilities of overall survival adjusted for CMV serostatus and disease status at transplantation were 63% (95% CI, 57% to 69%) for the Japanese, 54% (95% CI, 46% to 62%) for Whites who received ATG, and 60% (95% CI, 49% to 70%) for Whites who did not receive ATG (Figure 2B). Table 3 shows the causes of death. Relapse was the most frequent cause of death in all groups and accounted for about half of all deaths in all groups. The most frequent causes of non-relapse death for Japanese and Whites who received ATG were infection, GVHD, interstitial pneumonitis, and organ failure. On the other hand, for Whites who did not receive ATG, graft failure and infection were the most frequent causes of nonrelapse deaths.

Table 3. Causes of Death.

| Japanese (n = 257) | White, with ATG (n = 168) | White, no ATG (n = 92) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total death | 93 | 82 | 37 |

| Relapse | 54 (58%) | 41 (50%) | 18 (49%) |

| Graft failure | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (14%) |

| GVHD | 9 (10%) | 14 (17%) | 2 (5%) |

| Infection | 10 (11%) | 11 (13%) | 9 (24%) |

| Ipn/ARDS | 8 (9%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (5%) |

| Organ failure | 6 (6%) | 9 (11%) | 1 (3%) |

| Others* | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | — |

| Unknown | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | — |

Ipn indicates interstitial pneumonitis; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Other causes in Japanese include hemorrhage, n = 1, and thrombocytic microangiopathy, n = 1; in Whites with ATG include intracranial hemorrhage, n = 1; Epstein-Barr virus–associated lymphoproliferative disorder, n = 1; and anaplastic astrocytoma, n = 1.

The day-28 cumulative incidences of neutrophil recovery were higher for the Japanese (76%; 95% CI, 71% to 81%) compared with Whites who received ATG (66%; 95% CI, 59%to 73%; P =.02) and Whites who did not receive ATG (53%; 95%CI, 43% to 63%; P < .001). However, by day 42 cumulative incidences of neutrophil recovery were not different between the Japanese (88%; 95% CI, 84% to 92%) and Whites who received ATG (84%; 95% CI, 79%to 90%; P =.31) and those who did not receive ATG (82%; 95% CI, 74% to 90%; P = .22).

Discussion

The current analyses, in children with acute leukemia, sought to identify differences in acute and chronic GVHD risks after UCBT in a relatively homogenous population, the Japanese, to a more genetically diverse population, Whites. Three major observations have not been reported previously. First, grades II to IV and grades III to IV acute GVHD risks were not different between the 2 populations. Second, chronic GVHD risks were higher for Whites who received regimens that did not include ATG. Third, significant differences were not found in survival between the populations. Our findings are different from a previous report that compared GVHD risks and survival after HLA-matched sibling bone marrow transplantation [2]. In that report, acute and chronic GVHD risks were higher for younger Whites compared with the Japanese. We hypothesize in the setting of UCBT that the use of units mismatched to recipients at the major histocompatibility antigens may have ameliorated any advantages associated with the sharing of minor histocompatibility antigens in the more homogenous Japanese population. There are also qualitative and quantitative differences in the composition of bone marrow and UCB grafts leading to differences in post-transplant immune reconstitution, which may explain the observed differences between the current analysis and the observations after matched sibling transplantation [18,19]. It is also plausible that transplant period may have influenced the observations in the current analysis, which studied transplantations in a more recent era. A recent report showed lower GVHD risks and improved transplant outcomes in recent years compared with the previous era [20], and it may be that current GVHD prophylaxis regimens reduce the incidence of clinically significant GVHD in all patients, which further ameliorated the impact of genetic disparity for major and minor histocompatibility antigens.

Compared with the Japanese, who did not receive ATG, chronic GVHD was higher in Whites who did not receive ATG as part of their transplant conditioning but not for those who received ATG. We hypothesize the Japanese are inherently less likely to develop chronic GVHD. Despite the higher chronic GVHD in a subset of the Whites, we did not observe differences in survival between the treatment groups. Our findings differ from that of Narimatsu et al. [21] from the Japan Cord Blood Bank Network. In that report, chronic GVHD after UCBT was associated with improved survival. In the current analyses, despite the higher risks of chronic GVHD in 1 group, the severity of chronic GVHD was similar across the groups and may explain our inability to detect significant differences in survival between the groups. Generally, chronic GVHD adds to the burden of morbidity and mortality. Our study is limited by lack of data on health-related quality of life in patients with and without chronic GVHD. Another limitation is differential follow-up; non-ATG—containing preparative regimens for Whites is relatively recent, allowing for a median follow-up time of 3 years compared with 4 to 5 years for the other 2 groups. With extended follow-up it is possible that differences may exist between the non-ATG group and the other groups.

ATG is routinely included in the conditioning regimen package for UCBT in the United States and Europe to promote engraftment and lower GVHD risks [22]. However, ATG is seldom used for UCBT in Japan. Although we were unable to study immune recovery, delayed immune recovery and higher rate of infections with ATG is well documented [23] and has led to increasing use of fludarabine [24-26]. In the current analysis, we observed an absolute survival difference of 4% between the Japanese and Whites who did not receive ATG compared with an absolute difference of 10% between the Japanese and Whites who received ATG, suggesting that avoiding ATG-containing transplant conditioning regimens might be better for long-term survival.

Ethnic differences are reportedly contributors to related and unrelated bone marrow transplantation outcomes [2,27-29]. Ballen et al. [30] reported inferior survival in African Americans after UCBT, but the etiology for higher mortality was attributed to these patients having received units with greater HLA disparity and lower cell dose compared with Whites. In our study, despite the Japanese patients having received UCB units with lower cell dose compared with the U.S. Whites, survival rates were similar. We hypothesize that a minimum cell dose is needed for engraftment and selecting units with cell doses in excess of the minimum required does not lower mortality risks. It is possible differences may exists in the minimum cell dose for different populations. In the United States, reports from the right for International Blood and Marrow Transplant have consistently shown the minimum required cell dose as 3.0 × 107/kg. Among the Japanese, the minimum cell dose is 2.0 × 107/kg. Others have shown better matching between UCB units and their recipients can lower some of the excess TRM associated with UCBT [9]. We were unable to test for the effect of matching at the HLA-C locus or matching at the allele level, because these data were not available for all patients in the current analyses. At least among Whites, most transplantations reported in the current analysis are likely to be mismatched at 3 or greater HLA loci when considering allele-level HLA-match [31]. Whether there exist differences in survival between the Japanese and Whites when units are better HLA matched remains to be tested.

In summary, unlike in the setting of HLA-matched sibling transplantation, we did not observe differences in acute GVHD or overall mortality after UCBT between the Japanese and U.S. Whites. The observed higher chronic GVHD in a subset of transplantations in the United States warrants a study that focuses on health-related quality of life and long-term survival to fully evaluate the effect of chronic GVHD in these patients. Our findings are limited to children with acute leukemia. Because most older patients in the United States receive 2 UCB units and those in Japan a single UCB unit, a comparative analyses as performed in children remains a challenge.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Y. Kanda, Y. Morishima, M. Murata, and K. Miyamura for their helpful comments and insights as members of the JSHCT study committee and Dr. T. Naoe for his great support for this project.

Financial disclosure: Supported by Public Health Service grant U24-CA76518 from the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and a Health Resources and Services Administration contract (HHSH234200637015 C), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; a Young Researcher Overseas Visits Program for Vitalizing Brain Circulation (S2205) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; and a research grant for Allergic Disease and Immunology (H23-013) from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Ferrara JL, Levine JE, Reddy P, Holler E. Graft-versus-host disease. Lancet. 2009;373:1550–1561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60237-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh H, Loberiza FR, Jr, Zhang MJ, et al. Comparison of graft-versus-host-disease and survival after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation in ethnic populations. Blood. 2005;105:1408–1416. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersdorf EW, Malkki M, Hsu K, et al. 16th IHIW: International Histocompatibility Working Group in Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Int J Immunogenet. 2013;40:2–10. doi: 10.1111/iji.12022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laughlin MJ, Eapen M, Rubinstein P, et al. Outcomes after transplantation of cord blood or bone marrow from unrelated donors in adults with leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2265–2275. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi S, Iseki T, Ooi J, et al. Single-institute comparative analysis of unrelated bone marrow transplantation and cord blood transplantation for adult patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2004;104:3813–3820. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Zhang MJ, et al. Outcomes of transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood and bone marrow in children with acute leukaemia: a comparison study. Lancet. 2007;369:1947–1954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60915-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato K, Yoshimi A, Ito E, et al. Cord blood transplantation from unrelated donors for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Japan: the impact of methotrexate on clinical outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1814–1821. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atsuta Y, Kanda J, Takanashi M, et al. Different effects of HLA disparity on transplant outcomes after single-unit cord blood transplantation between pediatric and adult patients with leukemia. Haematologica. 2013;98:814–822. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.076042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eapen M, Klein JP, Sanz GF, et al. Effect of donor-recipient HLA matching at HLA A, B, C, and DRB1 on outcomes after umbilical-cord blood transplantation for leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndrome: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1214–1221. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horowitz M. The role of registries in facilitating clinical research in BMT: examples from the right for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(Suppl. 1):S1–S2. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atsuta Y, Suzuki R, Yoshimi A, et al. Unification of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation registries in Japan and establishment of the TRUMP System. Int J Hematol. 2007;86:269–274. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.06239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flowers ME, Kansu E, Sullivan KM. Pathophysiology and treatment of graft-versus-host disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:1091–1112. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70111-8. viii-ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;B34:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival analysis: Techniques for censored and truncated data. 2nd. New York: Springer Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang X, Zhang MJ. SAS macros for estimation of direct adjusted cumulative incidence curves under proportional subdistribution hazards models. Comput Methods Progr Biomed. 2011;101:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Loberiza FR, Klein JP, Zhang MJ. A SAS macro for estimation of direct adjusted survival curves based on a stratified Cox regression model. Comput Methods Progr Biomed. 2007;88:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiesa R, Gilmour K, Qasim W, et al. Omission of in vivo T-cell depletion promotes rapid expansion of naive CD4+ cord blood lymphocytes and restores adaptive immunity within 2 months after unrelated cord blood transplant. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:656–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanda J, Chiou LW, Szabolcs P, et al. Immune recovery in adult patients after myeloablative dual umbilical cord blood, matched sibling, and matched unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1664–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, et al. Reduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2091–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narimatsu H, Miyakoshi S, Yamaguchi T, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease following umbilical cord blood transplantation: retrospective survey involving 1072 patients in Japan. Blood. 2008;112:2579–2582. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-118893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurtzberg J, Prasad VK, Carter SL, et al. Results of the Cord Blood Transplantation Study (COBLT): clinical outcomes of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood transplantation in pediatric patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2008;112:4318–4327. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-098020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindemans CA, Chiesa R, Amrolia PJ, et al. Impact of thymoglobulin prior to pediatric unrelated umbilical cord blood transplantation on immune reconstitution and clinical outcome. Blood. 2014;123:126–132. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-502385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunstein CG, Eapen M, Ahn KW, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning transplantation in acute leukemia: the effect of source of unrelated donor stem cells on outcomes. Blood. 2012;119:5591–5598. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-400630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delaney C, Gutman JA, Appelbaum FR. Cord blood transplantation for haematological malignancies: conditioning regimens, double cord transplant and infectious complications. Br J Haematol. 2009;147:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohty M, Gaugler B. Advances in umbilical cord transplantation: the role of thymoglobulin/ATG in cord blood transplantation. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2010;23:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morishima Y, Kodera Y, Hirabayashi N, et al. Low incidence of acute GVHD in patients transplanted with marrow from HLA-A, B,DR-compatible unrelated donors among Japanese. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:235–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SJ, Klein J, Haagenson M, et al. High-resolution donor-recipient HLA matching contributes to the success of unrelated donor marrow transplantation. Blood. 2007;110:4576–4583. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-097386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morishima Y, Kawase T, Malkki M, et al. Significance of ethnicity in the risk of acute graft-versus-host disease and leukemia relapse after unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1197–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ballen KK, Klein JP, Pedersen TL, et al. Relationship of race/ethnicity and survival after single umbilical cord blood transplantation for adults and children with leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eapen M, Klein JP, Ruggeri A, et al. Impact of allele-level HLA matching on outcomes after myeloablative single unit umbilical cord blood transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2014;123:133–140. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-506253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]