Abstract

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is an increasing problem among the elderly. Multiple factors related to ageing, such as comorbidities, nutritional status and swallowing dysfunction have been implicated in the increased incidence of CAP in the older population. Moreover, mortality in patients with CAP rises dramatically with increasing age. Streptococcus pneumoniae is still the most common pathogen among the elderly, although CAP may also be caused by drug-resistant microorganisms and aspiration pneumonia. Furthermore, in the elderly CAP has a different clinical presentation, often lacking the typical acute symptoms observed in younger adults, due to the lower local and systemic inflammatory response. Several independent prognostic factors for mortality in the elderly have been identified, including factors related to pneumonia severity, inadequate response to infection, and low functional status. CAP scores and biomarkers have lower prognostic value in the elderly, and so there is a need to find new scales or to set new cut-off points for current scores in this population. Adherence to the current guidelines for CAP has a significant beneficial impact on clinical outcomes in elderly patients. Particular attention should also be paid to nutritional status, fluid administration, functional status, and comorbidity stabilizing therapy in this group of frail patients. This article presents an up-to-date review of the main aspects of CAP in elderly patients, including epidemiology, causative organisms, clinical features, and prognosis, and assesses key points for best practices for the management of the disease.

Keywords: clinical features, community-acquired pneumonia, elderly, etiology, management, prognosis, treatment

What is the magnitude of the problem?

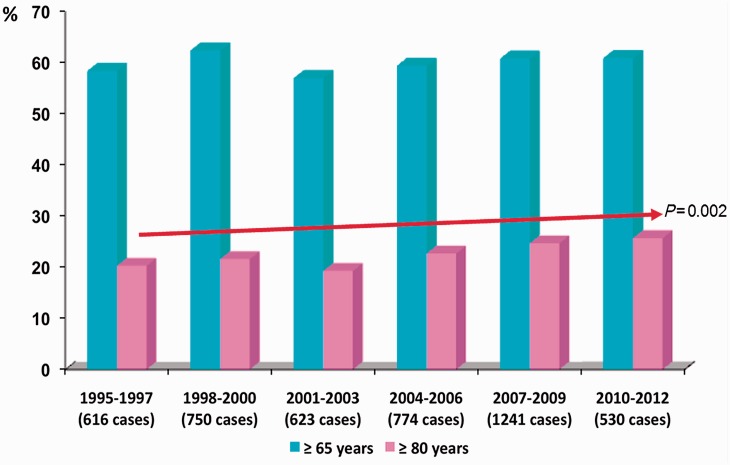

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is among the most common infectious diseases and causes significant morbidity and mortality [Mandell et al. 2007]. CAP is an increasing problem among the elderly. CAP rates in older adults are rising as a consequence of an overall increase in the elderly population [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003]. It has been reported that CAP is the third most common reason for hospitalization for persons aged 65 years and over [May et al. 1991], and in fact nearly 50% of hospitalized patients with CAP are in this age group [Niederman et al. 1998]. Interestingly, in a prospective cohort of 4534 hospitalized patients with CAP (1995–2012), we found that the number of patients aged 80 and over has increased significantly in the last 17 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of older patients among 4534 hospitalized CAP cases from 1995 to 2012 in a tertiary teaching hospital in Barcelona, Spain.

The incidence of hospitalized CAP is much higher among elderly patients. In a US Medicare cohort of patients ≥65 years, the incidence was 18.3/1000 population and rose more than fivefold, from 8.4/1000 in those aged 65–69 years to 48.5/1000 in those aged 90 years or older [Kaplan et al. 2002]. In a Spanish cohort study of 11,240 inhabitants aged ≥65 years conducted from 2002 to 2005, the annual incidence rate of CAP was 13.9/1000 elderly persons/year [Vila-Corcoles et al. 2009]. As in the US cohort, the incidence also increased with age in this population (from 9.9% in those aged 65–74 years to 16.9% in those aged 75–84 years, and to 29.4% in the over 85s) [Ochoa-Gondar et al. 2008].

Furthermore, mortality in hospitalized CAP patients ranges between 10% and 25%, being particularly high in older adults and in patients with comorbidities [Fernández-Sabé et al. 2003]. In the Spanish cohort study just mentioned the 30-day case-fatality rate rose dramatically with increasing age (7.2% in those aged 65–74 years, 13.5% in those aged 75–84 years and 23.5% in the over-85 s) [Ochoa-Gondar et al. 2008].

Key points

– The elderly population is at an increased risk for acquiring CAP and is more likely to suffer from severe disease.

– In the coming years, rates of CAP in older adults will rise due to the overall increase in the elderly population.

– CAP in elderly patients is associated with high morbidity and mortality. The risk of poor outcome increases with age.

What are the predisposing factors for CAP in older patients?

Several factors have been linked with an increased risk of CAP in the elderly. Even in healthy ageing without comorbidity, immunity and lung function may be impaired. In older patients, nasal mucociliary clearance has been shown to be less efficient [Ho et al. 2001]. Age-related effects on pulmonary host defenses have been reported, such as mechanical barriers, phagocytic activity, humoral and T-cell immunity, in animal and human models [Meyer, 2001]. Similarly, changes in the immune system associated with ageing involve, in particular, a decline in peripheral antigen-specific T- and B-cell function. Finally, the function of natural killer cells, macrophages, and neutrophils also decreases in the elderly [Meyer, 2001; Renshaw et al. 2002; Janssens and Krause, 2004].

A variety of methodological approaches have been tested in attempts to identify independent risk factors for CAP in the elderly. Jackson and colleagues identified lung diseases, heart diseases, weight loss, poor functional status, and smoking as independent predictors for CAP in older patients [Jackson et al. 2009]. Riquelme and colleagues found that suspicion of swallowing disorders, large volume aspiration, malnutrition, hypoproteinemia (<60 mg/dl), hypoalbuminemia (<30 mg/dl), prior antibiotic therapy, poor quality of life (performance status ≤70) and bedridden status were associated with a higher risk of CAP [Riquelme et al. 1996]. Other authors have found possible associations between history of hospitalization for CAP in the previous 2 years [Vila-Corcoles et al. 2009], diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, renal disease, excessive alcohol intake [Skull et al. 2009], use of antipsychotic drugs [Trifirò et al. 2010], socio-economic status [Farr et al. 2000] and contact with children [Fung and Monteagudo-Chu, 2010], with a higher risk of CAP in elderly. Although comorbidities have been associated with CAP in these patients, the exact mechanisms involved have not been fully established [Donowitz and Cox, 2007].

Several researchers have stressed the role of the silent aspiration of gastric and oropharyngeal contents into the respiratory tract in the pathogenesis of pneumonia among older adults [Marik and Kaplan, 2003]. In addition, it is well known that oropharyngeal bacterial colonization is more common in elderly patients [Niederman, 1994] and that oropharyngeal deglutition is impaired with age [Tracy et al. 1989]. Silent aspiration is an important risk factor for CAP as well as nosocomial pneumonia in the elderly. Using a scanning technique with indium 111 chloride to assess silent aspirations, Kikuchi and colleagues found that patients with positive scans over the lungs were more likely to have CAP than those without positive scans [Kikuchi et al. 1994]. More recently, researchers have found a strong association between oropharyngeal dysphagia and CAP, and consider it an independent risk factor for CAP in the elderly. Clinical assessment of oropharyngeal dysphagia by the gold standard videofluoroscopy showed that the prevalence of dysphagia and impaired efficacy and safety of swallowing among elderly patients with CAP was very high compared with matched controls [Almirall et al. 2013].

It has been described in elderly patients that enhanced oral care is a simple and easily intervention that has the potential to remove pathogenic bacteria from oral mucosa and improve the swallowing reflex, reducing two well-known risk factors for CAP. Moreover, longitudinal studies in older adults have demonstrated that regular physical activity can improve physical performance, reduce risk of physical disability, and delay functional decline, which is associated with a higher risk of acquiring pneumonia and a higher severity of the disease [Juthani-Mehta et al. 2013].

Key points

– In elderly patients, special attention should be paid to patients with swallowing disorders, malnutrition, high rate of comorbidities, poor functional and bedridden status as predisposing factors for CAP.

– Enhanced oral hygiene and regular physical activity could reduce CAP incidence.

Do the causative organisms of CAP differ between older and younger patients?

The spectrum of etiological pathogens in elderly patients with CAP is diverse and shows substantial variations between studies (Table 1). These findings can be explained at least in part by geographical and seasonal characteristics, differences in study design and population, and most importantly, differences in methods and the extent of efforts to define a causal pathogen [Thiem et al. 2011]. In addition, the absence of productive cough and the common use of antibiotics before cultures have limited the performance of microbiological tests in older patients [Donowitz and Cox, 2007].

Table 1.

Causative microorganisms of CAP in elderly patients.

| Fernández-Sabé et al. [2003] ≥80 years hospitalized | Zalacain et al. [2003] ≥65 years hospitalized |

El Solh et al. [2001] ≥75 years |

Riquelme et al. [1996] ≥65 years hospitalized | Vila-Corcoles et al. [2009] ≥65 years hospitalized and outpatients | Rello et al. [1996] ≥65 years ICU | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAP | Nursing home | ||||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 23% | 49% | 14% | 9% | 36% | 49% | 29% |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 5% | 13% | 7% | 2% | 0% | 6% | 7% |

| Legionella sp. | 1% | 9% | 9% | 0% | 6% | 3% | 3% |

| Other atypical | 1% | 17% | 2% | 0% | 32% | 10% | 1% |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0% | 4% | 7% | 29% | 0% | 5% | 1% |

| MRSA | 0% | 0% | 0% | 6% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1% | 6% | 2% | 4% | 2% | 15% | 3% |

| Other Gram-negative bacilli | 2% | 6% | 12% | 11% | 0% | 6% | 3% |

| Virus | 8% | 3% | 2% | 0% | – | – | 1% |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 10% | – | – | – | – | – | – |

CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ICU, intensive care unit; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common pathogen identified (36–49%). The incidence of pneumococcal pneumonia generally increases with age. Nontypeable strains of Haemophilus influenzae are the second most frequently identified microorganisms. Moreover, the frequency of Legionella pneumophila as a causative agent of CAP in the elderly ranges from 1% to 9% [Fernández-Sabé et al. 2003; Riquelme et al. 1997].

Staphylococcus aureus occurs in fewer than 7% of cases of CAP, although it is thought to have a greater role in nursing-home-associated pneumonias [Janssens and Krause, 2004]. In patients aged 75 and older with severe nursing-home-acquired pneumonia, S. aureus was the main pathogen identified (29%) [El Solh et al. 2001]. However, in a recent Spanish study of 150 consecutive cases of nursing-home-acquired pneumonia, the most commonly identified organisms were: S. pneumoniae (58%), Enterobacteriaceae (9%), atypical bacteria (7%), respiratory viruses (5%), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (5%) and L. pneumophila (5%) [Polverino et al. 2010]. On the other hand, community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) affects mainly young non-immunocompromised patients without risk factors. Moreover, CA-MRSA is much more frequent in Northern America than in Europe.

Over the past 10 years, the incidence of Gram-negative bacilli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in older patients has ranged widely depending on the study, from 2–3% to 15.5% [Riquelme et al. 1997; Fernández-Sabé et al. 2003; Vila-Corcoles et al. 2009]. These discrepancies may be explained in part by differences in the study populations, such as the inclusion or noninclusion of nursing-home patients, the prevalence of comorbidities, and the degree of the decline in functional status and CAP severity. Information regarding resistance in this group of causative agents of CAP is scarce. Moreover, in elderly patients increased risk of aspiration as well as functional impairment, rather than age alone or comorbidity, are important risk factors for infection with drug-resistant microorganisms [Ewig et al. 2010]. Although infections due to extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli are steadily increasing in many countries, no multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli were documented in a study of healthcare-associated pneumonia [Carratalà et al. 2007].

The proportion of CAP caused by atypical agents in the elderly is usually low. However, some researchers [Zalacain et al. 2003] reported that atypical pathogens are more common in older patients (up to 20% of cases) than in younger ones. In these studies, most atypical bacteria in CAP episodes were Chlamydia spp., and were diagnosed by serological tests. In our experience, atypical agents are rarely identified in elderly patients [Fernández-Sabé et al. 2003].

Influenza, parainfluenza, and respiratory syncytial viruses are other etiologic agents that should be considered in this population. In a prospective multicenter study in Germany, the prevalence of CAP due to influenza viruses was higher in patients aged ≥65 years than in those below this age [Kothe et al. 2008]. A very different scenario was found during the pandemic (H1N1) 2009, with the emergence of age as a protective factor for influenza infection, severe respiratory disease, and pneumonia due to influenza [Viasus et al. 2011; Chowell et al. 2009]. However, during post-pandemic influenza seasons, the data indicate an upward shift in the age-distribution of influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 [Viasus et al. 2012; Bolotin et al. 2012].

Although the common difficulty in swallowing among elderly persons has been widely demonstrated, the incidence and relevance of aspiration pneumonia is still controversial. In an analysis of CAP in very old patients (≥80 years) aspiration pneumonia was the second most common cause of CAP, accounting for 10% of cases [Fernández-Sabé et al. 2003]. Recently, Teramoto and colleagues found that the prevalence of aspiration pneumonia in CAP and hospital-acquired pneumonia in 22 hospitals in Japan was high and increased with age (from nearly 20% in those aged 50–59 years to 80% in patients aged 70) [Teramoto et al. 2008]. However, the swallowing function was not tested uniformly and the study did not include bacterial examination. The frequency of aspiration pneumonia in other studies has probably been underestimated as a result of the difficulty in diagnosing silent aspiration; moreover, the microbiological data in these patients are often negative, as invasive diagnostic methods are not performed [Marik, 2001].

As outlined by Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society (IDSA/ATS) guidelines, there is not a specific indication for diagnostic workup in elderly patients. Like in the general population, there are some conditions, such as severe pneumonia, failure of outpatient antibiotic therapy, immunosuppression or chronic severe illness, that require an etiological diagnosis.

We suggest a step-by-step diagnostic workup in patients hospitalized with pneumonia, where the pneumococcal urinary antigen test is reserved for those patients in whom demonstrative results of sputum Gram staining are not available (poor-quality samples and/or samples in which predominant morphotypes were not detected). A legionella urinary antigen test and specific Legionella cultures should be performed in patients who have negative pneumococcal urinary antigen test. When there is a suspicion of influenza-related pneumonia, particularly during the winter months, influenza testing (by polymerase chain reaction from nose–pharyngeal swab) may be important for patient care and infection control [Keipp Talbo and Falsey, 2010].

Key points

– S. pneumoniae is the most common pathogen in the elderly; the frequency of atypical agents is usually low.

– Infection with aspiration pneumonia and drug-resistant microorganisms should be taken into account due to their prevalence and their implications for the choice of appropriate treatment.

– Influenza is a serious problem in elderly patients.

Do clinical features of CAP differ in the elderly?

A hundred years ago, Sir William Osler stated that ‘in old age, pneumonia may be latent, coming on without chill, the cough and expectoration are slight, the physical signs ill-defined and changeable, and the constitutional symptoms out of all proportion. Importantly, fever may be absent’.

Since then, other investigators have found that the clinical presentation of CAP may differ in the elderly compared with other age groups; it may be subtle, and may lack the typical acute symptoms observed in younger adults (Table 2).

Table 2.

Main clinical features on admission in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia.

| Fernández-Sabé et al. [2003] ≥80 years hospitalized | Zalacain et al. [2003] ≥65 years hospitalized | Riquelme et al. [1996] ≥65 years hospitalized | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cough | – | 81% | 66% |

| Fever | 68% | 76% | 63% |

| Dyspnea | – | 70% | 70% |

| Purulent sputum | 53% | 22% | – |

| Chills | 45% | 53% | 23% |

| Pleural pain | 37% | 43% | 34% |

| Altered mental state | 21% | 26% | 45% |

| Arthromyalgias | 8% | 19% | – |

| Headache | 7% | 15% | – |

| Asthenia | – | 39% | 57% |

Riquelme and colleagues reported an incomplete clinical picture of CAP in older patients. Nearly 36% of this cohort of elderly patients did not present fever, and 7% had no symptoms or signs of infection [Riquelme et al. 1997]. They also reported that altered mental status, a sudden decline in functional capacity and worsening of underlying diseases were very common and may be the only symptoms of CAP in the elderly. Moreover, Metlay and colleagues found that advanced age was associated with lower symptom reporting. The prevalence of symptoms related to the febrile response and pain fell notably, while smaller differences were observed regarding respiratory symptoms. Owing to its unusual presentation, diagnosis of CAP in the elderly population was often delayed [Metlay et al. 1997].

Other researchers have reported the association of cough, expectoration and pleuritic chest pain in 30% of cases and altered mental status in 26% [Zalacain et al. 2003]. Moreover, in an analysis of an observational cohort of adults hospitalized for CAP in Spain, very elderly patients (aged ≥80 years) complained of pleuritic chest pain, headache, and myalgias less frequently than younger patients. They also had less fever, and were more likely to have altered mental status. However, when the clinical presentation of pneumococcal pneumonia was analyzed, no significant differences between age groups were found with regard to the classic bacterial pneumonia syndrome [Fernández-Sabé et al. 2003].

Key points

– Clinical presentation of pneumonia in the elderly may be subtle, and may be afebrile.

– Altered mental status, a sudden decline in functional capacity, and worsening of underlying diseases may be the only findings.

– Physicians should be alert to the diagnosis of CAP in elderly patients, even in the absence of the classic symptoms.

Prognostic factors

Are CAP-specific scores useful for predicting prognosis in older patients?

Several years ago, Fine and colleagues developed the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), a score comprising 20 items that are summed to place the patient in one of five risk categories [Fine et al. 1997]. Another commonly used and easier to determine prognostic score, the CURB-65 [Confusion, Urea >7 mmol/l, Respiratory rate (RR) ≥30/min, Blood pressure (systolic blood pressure (BP) <90 or diastolic BP ≤60 mmHg) and age ≥65 years] was developed by the British Thoracic Society [Lim et al. 2003]. These scores attribute considerable importance to age, which is a major factor in the prediction of 30-day mortality in patients with CAP.

In recent years, many studies have evaluated the usefulness of the PSI in elderly population, with controversial results. Ewig and colleagues reported that the PSI provided an accurate estimate of the risk of death in 168 CAP patients ≥65 years, and that it reliably predicted need for ICU admission and length of hospital stay [Ewig et al. 1999]. However, in 144 very elderly patients (≥80 years old) it was observed that PSI high-risk groups (classes IV and V) did not perform well in discriminating survivors from nonsurvivors (sensitivity 100%, specificity 15%). When only PSI class V was defined as a high-risk group, its specificity was considerably greater, and it retained high sensitivity [Naito et al. 2006].

Other researchers have evaluated the usefulness of CURB-65 and its simplified form CRB65 to predict mortality in the elderly. Spanish investigators reported an acceptable ability to classify mortality risk in elderly patients with CAP for CRB65 (for a breakpoint ≥2, sensitivity was 60% and specificity was 80%) [Vila Córcoles et al. 2010]. Another study in the same cohort of patients tested the modified CRB75 (with the same criteria as CRB65, except for the age criterion, which was ≥75 years), obtaining a better ROC curve than for CRB65 (0.735 versus 0.681; p < 0.01) [Ochoa Gondar et al. 2013]. Moreover, a study from the Netherlands testing the CURB-65 in a primary health setting reported good performance with a cutoff score of 2 or higher [Bont et al. 2008]. These results are partially at variance with previous reports [Lim and Macfarlane, 2001; Conte et al. 1999; Ewig et al. 1999], which suggested that this score performed less well in the elderly population, especially in those aged ≥75 years. Significantly, however, most authors noted that in the elderly population age per se is not an independent predictor of mortality.

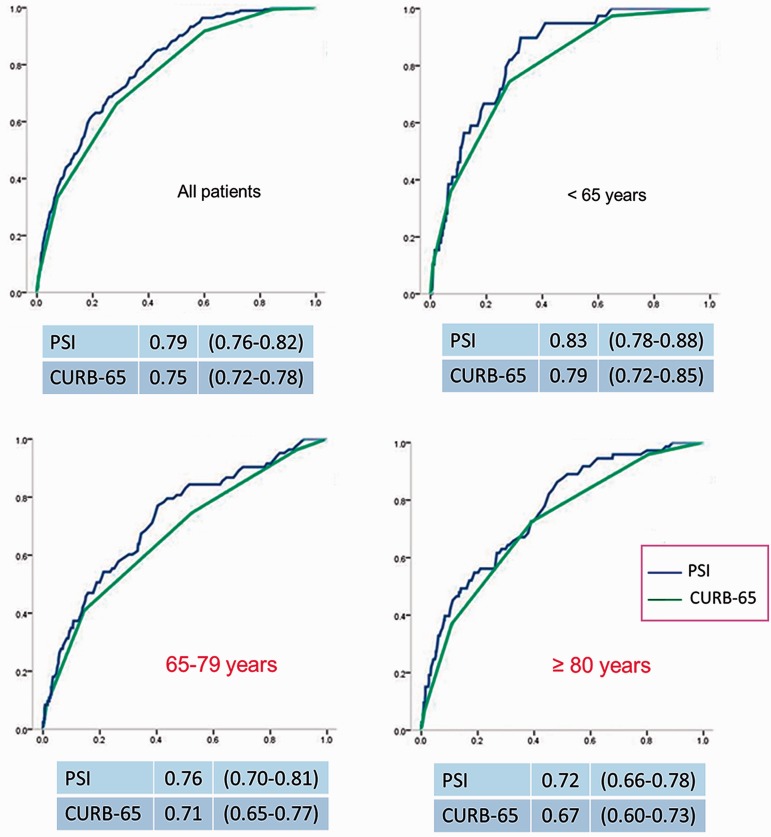

Chen and colleagues concluded that both PSI and CURB-65 present a decreased discriminative power with advancing age. Using the originally recommended cutoff points for PSI or CURB-65 may overestimate severity in the elderly and very elderly populations. The investigators suggest the need for large, prospective studies to determine the best weight for the age variable in this context [Chen et al. 2010]. Interestingly, in our prospective cohort of hospitalized patients with CAP we found that the usefulness of PSI and CURB-65 for predicting mortality decreases as age increases (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Area under receiver operating characteristic curve (95% confidence interval) for predicting mortality of PSI and CURB-65 scores by age group in 4534 hospitalized cases with community-acquired pneumonia in a tertiary teaching hospital in Barcelona, Spain. PSI, Pneumonia Severity Index; CURB-65, Confusion, Urea >7 mmol/l, Respiratory rate ≥30/min, Blood pressure (systolic blood pressure <90 or diastolic blood pressure ≤60 mmHg) and age ≥65 years.

Recently, new scoring systems have been proposed for elderly patients. In a cohort of CAP patients which included a substantial proportion of older and oncologic patients, an enhanced CURB score (age in years and adding three comorbid conditions: solid cancer, metastatic cancer, stroke) performed better than both CURB-65 and PSI for predicting mortality [Abisheganaden et al. 2012]. Moreover, it is known that in advancing age both confusion and increased urea are common and may be affected by multiple confounding factors. For this reason, Myint and colleagues also proposed a new set of criteria named SOAR (Systolic BP, Oxygenation, Age and Respiratory rate), for use in older patients with CAP instead of CURB [Myint et al. 2006]. However, most authors favor modifying existing scores in order to improve their prognostic value rather than creating new tools for elderly patients [Brito and Niederman, 2010].

Are biomarkers useful for predicting prognosis in older patients?

Markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) level, white blood cell (WBC) count, procalcitonin level, proadrenomedullin, and natriuretic peptides are increasingly being used to assess the prognosis of patients with CAP. However, few studies have explored the value of biomarkers in the elderly.

Ahkee and colleagues found an inverse relation between mortality and WBC. In elderly patients with CAP, the mortality rate was seven times higher in those without leukocytosis on hospital admission than in the group with the condition. The authors suggest that the lack of a systemic inflammatory response may be seen as a marker of an abnormal immune system [Ahkee et al. 1997]. However, a prospective study of 897 patients admitted with CAP found no difference in interleukin (IL)-6 or in IL-10 levels between younger patients and those older than 65 years. This study presents further data rejecting the view that older patients display a muted response to pneumonia [Kelly et al. 2009].

More recently, the usefulness of other biomarkers such as CRP and procalcitonin in elderly patients has been evaluated. An analysis of a retrospective cohort of 438 patients ≥65 years with CAP did not reveal any association between CRP or WBC and mortality, or between CRP or WBC and pneumonia severity [Thiem et al. 2009]. The investigators stress that the same phenomenon has been identified for the prognostic value of risk scores. On the other hand, a recent study [Kim et al. 2013] reported a good correlation between procalcitonin level and both PSI and CURB-65 in elderly patients. However, no relationship was found between procalcitonin and mortality.

What factors are associated with mortality in older patients?

Several studies of CAP [Riquelme et al. 1996; Rello et al. 1996; Garcia-Ordoñez et al. 2001] have failed to associate age alone with a higher risk of mortality. In a cohort of patients with severe CAP admitted to the ICU, no difference in mortality rate was found between patients aged 65–75 years and those over 75. This finding stresses how inappropriate it is to withhold intensive care from elderly patients on account of age, because more than half may survive the respiratory infection and may return to their previous lifestyle [Rello et al. 1996].

The data regarding the impact of comorbidities in the outcome of elderly population with CAP are controversial. Some researchers identify comorbid illness as one of the most important prognostic factors [Conte et al. 1999; Ma et al. 2011]. An association has also been found between certain specific comorbid conditions and mortality, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cerebrovascular disease [Neupane et al. 2010], renal disease, and immunosuppression [Skull et al. 2009]. Nevertheless, many other studies of CAP in the elderly have not found an association between comorbid illness and mortality [Lim and Macfarlane, 2001; Janssens et al. 1996; Rello et al. 1996; Riquelme et al. 1996].

Moreover, several independent prognostic factors for mortality in the elderly have been identified (Table 3). Many studies have reported the association between mortality and the severity of pneumonia, as expressed by its extension and consequent respiratory failure [Riquelme et al. 1997; García-Ordóñez et al. 2001; Naito et al. 2006; Skull et al. 2009]. Another group of prognostic factors for poor outcome is related to an inadequate response to infection, such as septic shock at admission, apyrexia, and altered mental status [Riquelme et al. 1997; García-Ordóñez et al. 2001; Fernández-Sabé et al. 2003]. The third group of factors related to mortality includes host characteristics: low functional status, bedridden status, poor nutritional status, and passive or active smoking have all been related to poor outcome in elderly patients with CAP [Skull et al. 2009; Naito et al. 2006; Riquelme et al. 1997; Ma et al. 2011; Vecchiarino et al. 2004].

Table 3.

Factors associated with poor outcome for community-acquired pneumonia in elderly patients.

| Severity of pneumonia: |

| ≥3 lobes affected |

| tachypnea |

| severe hypoxemia |

| hypercapnia |

| Inadequate response to infection: |

| shock at admission |

| apyrexia |

| altered mental status |

| Factors related with the host: |

| comorbidities |

| low functional status |

| bedridden status |

| poor nutritional status |

| passive or active smokers |

Key points

– The accuracy of CURB-65 and PSI for predicting outcome in CAP decreases with advancing age.

– There are insufficient data to sustain the usefulness of biomarkers in older patients.

– Severity and extension of pneumonia, inadequate response to infection, and low functional status are the principal factors associated with mortality in older patients.

What treatment should elderly patients with CAP receive?

Antimicrobials are the cornerstone of therapy for CAP in any population, including the elderly. The most recently published clinical practice guidelines for CAP do not recommend different treatments for elderly patients [Mandell et al. 2007; Woodhead et al. 2011].

According to the IDSA/ATS guidelines, in the outpatient setting, the recommended empirical treatment is a macrolide for previously healthy patients who have not used antimicrobials within the previous 3 months. However, in some countries macrolide-resistant S. pneumoniae are frequent [Jones et al. 2010; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2005–2013]. A respiratory fluoroquinolone or a beta-lactam plus a macrolide are recommended for patients with comorbidities. In hospitalized patients with nonsevere CAP, the recommendation is a respiratory fluoroquinolone or a beta-lactam plus a macrolide. In severe CAP, a combination of antibiotics is usually recommended. A beta-lactam plus either azithromycin or a respiratory fluoroquinolone are preferred. In patients with predisposing factors for P. aeruginosa or other Gram-negative bacilli an antipneumococcal, antipseudomonal beta-lactam plus either a quinolone or an aminoglycoside and azithromycin should be considered [Mandell et al. 2007]. If MRSA is considered as a possible causative organism, guidelines recommend adding vancomycin or linezolid.

Importantly, it has been demonstrated that good adherence to the 2007 IDSA/ATS guidelines for CAP has a significant beneficial impact on clinical outcomes in elderly patients. In a cohort of 1649 hospitalized CAP patients aged 65 years, adherence to guidelines was associated with a significantly shorter time taken to achieve clinical stability compared with nonadherence. Adherence to guidelines was also associated with shorter length of stay (8 days versus 10 days) and decreased overall in-hospital mortality (8% versus 17%) [Arnold et al. 2009]. Recently, a Danish study in older patients with CAP reported that the CAP guidelines were mainly applied with regard to diagnostic tests and treatment initiation whereas nutrition and mobilization were neglected or only sporadically addressed [Lindhardt et al. 2013].

Several studies have shown that elderly persons hospitalized for CAP may be at increased risk of functional loss during hospitalization and after discharge. A lack of recovery in the first 3 months is associated with an increased risk of hospital readmission and 1-year mortality [El Solh et al. 2006]. For this reason, rehabilitation of elderly patients during hospitalization and post-discharge should be encouraged [Klausen et al. 2012]. In addition, in elderly patients special attention should also be paid to the global assessment, including aspects such as nutritional status, fluid therapy, comorbidity stabilizing therapy, and patient information. A randomized, controlled trial demonstrated that nutritional supplementation in older patients admitted for pneumonia achieved a faster and greater physical recovery [Woo et al. 1994]. Similarly, the use of a three-step critical pathway, including early mobilization, was safe and effective in reducing the length of hospital stay for CAP and did not adversely affect patient outcomes [Carratalà et al. 2012].

Importantly, a recent study showed that in elderly patients with CAP, the decision to use a do not resuscitate (DNR) order was taken in nearly 30% of hospitalized patients [Oshitani et al. 2013]. In this study physicians were more inclined to propose DNR orders when CAP patients demonstrated older in age (more than 75 years), poor performance status, dementia, aspiration, low albumin, extensive consolidation, and respiratory failure. The decision to use DNR orders did not make physicians choose less-intense antimicrobial treatments. Nevertheless effort to detect bacteria was not made in the DNR group as elaborately as in the non-DNR group. They also found that the DNR group has higher 30-day mortality.

Key points

– Adherence to guidelines for treatment of CAP is highly recommended in the elderly.

– Risk factors for P. aeruginosa, MRSA, and other Gram-negative bacilli have to be considered when selecting antibiotic treatment.

– Physicians should pay special attention to nutrition, early mobilization, and comorbidity-stabilizing therapy in older patients.

Which vaccines should be administered to elderly patients in order to prevent CAP?

Vaccination remains the primary preventive strategy for CAP in the elderly. Guidelines recommend immunization against both influenza virus and S. pneumoniae in patients above the age of 65. Nevertheless, both vaccinations are substantially underused in this vulnerable population.

Recent meta-analyses provide evidence supporting the recommendation of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV) to prevent invasive pneumococcal disease in adults, but, with regard to adults with chronic illness, do not find compelling evidence to support the routine use of PPV to prevent all-cause pneumonia or mortality [Moberley et al. 2013; Huss et al. 2009]. However, the 23-valent vaccine prevented pneumococcal pneumonia and reduced mortality due to pneumococcal pneumonia in nursing-home residents in a randomized trial [Maruyama et al. 2010]. Moreover, in a matched case–control study in patients aged ≥65 years and hospitalized with CAP, Domínguez and colleagues found an effectiveness of 23.6% for the PPV for preventing hospitalizations due to pneumonia [Domínguez et al. 2010].

Recently, randomized trials have showed that 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) induces a greater functional immune response than PPSV23 for the majority of serotypes covered by PCV13 in adults [Jackson et al. 2013]. Consequently, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved the use of the PCV13 in this population. However, studies evaluating the clinical effectiveness of PCV vaccination in adults are lacking. Similarly, recently it was suggested that there is no epidemiological reason to vaccinate older adults with PCV due to the fact that PCV vaccination of children has also reduced the incidence of conjugate vaccine-serotype disease in older adults.

Regarding the impact of influenza vaccination on CAP, a Cochrane meta-analysis did not find any effect on hospital admissions, incidence of pneumonia, or complication rates between vaccinated and unvaccinated patients [Jefferson et al. 2010]. However, in the elderly, vaccinations against influenza and pneumococcus are associated with reduced risk of hospitalization for heart disease and acute cardiovascular events. These findings highlight the benefits of vaccination and support efforts to increase vaccination rates among the elderly [Nichol et al. 2003; Lamontagne et al. 2008].

Key points

– Current guidelines recommend vaccination against S. pneumoniae and influenza in all patients ≥65 years.

– Nevertheless, coverage of both vaccinations remains low; physicians should promote their implementation.

Conclusions

The elderly population is at an increased risk of acquiring CAP and is more likely to suffer from severe disease. In the coming years, CAP cases in older adults will increase as a consequence of the overall increase in the elderly population. The spectrum of etiological pathogens in elderly patients with CAP is diverse and shows substantial variations between studies, but S. pneumoniae is still the most common pathogen. Moreover, drug-resistant microorganisms and aspiration pneumonia should also be borne in mind. Significantly, the clinical presentation in elderly patients may be subtle and may lack the typical acute symptoms, due to the lower local and systemic inflammatory response. This suggests the need to maintain a high suspicion of CAP in elderly patients, even if they present with atypical symptoms such as falls, altered mental status and/or worsening of underlying diseases. The usefulness of CAP-specific scores and biomarkers to predict outcomes in elderly population is controversial; we probably need to set different cutoff points for current scores. New scales developed recently for assessing severity in elderly patients with CAP need further evaluation. Antimicrobial selection for elderly patients with CAP is the same as for younger adult populations; however, when choosing the correct treatment, physicians must carefully check for possible risk factors for resistant microorganisms and evaluate the possibility of aspiration pneumonia. In addition to antibiotic treatment, special attention should be paid to the management of older patients, including nutrition, rehabilitation, comorbidity stabilization, and early mobilization. Preventive steps such as pneumococcal and influenza vaccination and measures aimed at improving nutritional status may help to reduce CAP incidence.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria de la Seguridad Social (grant number 11/01106) and Spain’s Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund ‘A way to achieve Europe’ and Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (grant number REIPI RD12/0015). Dr Simonetti is the recipient of a research grant from the IDIBELL, Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute. Dr Viasus is the recipient of a research grant from the REIPI. Dr Garcia-Vidal is the recipient of a Juan de la Cierva research grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

Conflict of interest statement

No authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Abisheganaden J., Ding Y., Chong W., Heng B., Lim T. (2012) Predicting mortality among older adults hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia: an enhanced confusion, urea, respiratory rate and blood pressure score compared with pneumonia severity index. Respirology 17: 969–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahkee S., Srinath L., Ramirez J. (1997) Community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: association of mortality with lack of fever and leukocytosis. South Med J 90: 296–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almirall J., Rofes L., Serra-Prat M., Icart R., Palomera E., Arreola V., et al. (2013) Oropharyngeal dysphagia is a risk factor for community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Eur Respir J 41: 923–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold F., LaJoie A., Brock G., Peyrani P., Rello J., Menéndez R., et al. (2009) Improving outcomes in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia by adhering to national guidelines: Community-Acquired Pneumonia Organization International cohort study results. Arch Intern Med 169: 1515–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotin S., Pebody R., White P., McMenamin J., Perera L., Nguyen-Van-Tam J., et al. (2012) A new sentinel surveillance system for severe influenza in England shows a shift in age distribution of hospitalised cases in the post-pandemic period. PLoS One 7: e30279–e30279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bont J., Hak E., Hoes A., Macfarlane J., Verheij T. (2008) Predicting death in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective validation study reevaluating the CRB-65 severity assessment tool. Arch Intern Med 168: 1465–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito V., Niederman M. (2010) Predicting mortality in the elderly with community-acquired pneumonia: should we design a new car or set a new ‘speed limit'? Thorax 65: 944–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carratalà J., Garcia-Vidal C., Ortega L., Fernández-Sabé N., Clemente M., Albero G., et al. (2012) Effect of a 3-step critical pathway to reduce duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy and length of stay in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 172: 922–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carratalà J., Mykietiuk A., Fernández-Sabé N., Suárez C., Dorca J., Verdaguer R., et al. (2007) Health care-associated pneumonia requiring hospital admission: epidemiology, antibiotic therapy, and clinical outcomes. Arch Intern Med 167: 1393–1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2003) Trends in aging - United States and worldwide. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 52: 101–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Chang S., Liu J., Chan R., Wu J., Wang W., et al. (2010) Comparison of clinical characteristics and performance of pneumonia severity score and CURB-65 among younger adults, elderly and very old subjects. Thorax 65: 971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowell G., Bertozzi S., Colchero M., Lopez-Gatell H., Alpuche-Aranda C., Hernandez M., et al. (2009) Severe respiratory disease concurrent with the circulation of H1N1 influenza. N Engl J Med 361: 674–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte H., Chen Y., Mehal W., Scinto J., Quagliarello V. (1999) A prognostic rule for elderly patients admitted with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 106: 20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez A., Izquierdo C., Salleras L., Ruiz L., Sousa D., Bayas J., et al. (2010) Effectiveness of the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in preventing pneumonia in the elderly. Eur Respir J 36: 608–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donowitz G., Cox H. (2007) Bacterial community-acquired pneumonia in older patients. Clin Geriatr Med 23: 515–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Solh A., Sikka P., Ramadan F., Davies J. (2001) Etiology of severe pneumonia in the very elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163: 645–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Solh A., Pineda L., Bouquin P., Mankowski C. (2006) Determinants of short and long term functional recovery after hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: role of inflammatory markers. BMC Geriatr 6: 12–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2005–2013) European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network. Available at: http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/antimicrobial_resistance/database/Pages/map_reports.aspx.

- Ewig S., Kleinfeld T., Bauer T., Seifert K., Schäfer H., Göke N. (1999) Comparative validation of prognostic rules for community acquired pneumonia in an elderly population. Eur Respir J 14: 370–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewig S., Welte T., Chastre J., Torres A. (2010) Rethinking the concepts of community-acquired and health-care-associated pneumonia. Lancet Infect Dis 10: 279–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr B., Bartlett C., Wadsworth J., Miller D. (2000) Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia diagnosed upon hospital admission. British Thoracic Society Pneumonia Study Group. Respir Med 94: 954–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Sabé N., Carratalà J., Rosón B., Dorca J., Verdaguer R., Manresa F., et al. (2003) Community-acquired pneumonia in very elderly patients: causative organisms, clinical characteristics, and outcomes. Medicine (Baltimore) 82: 159–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine M., Auble T., Yealy D., Hanusa B., Weissfeld L., Singer D., et al. (1997) A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 336: 243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung H., Monteagudo-Chu M. (2010) Community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 8: 47–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Ordóñez M., García-Jiménez J., Páez F., Alvarez F., Poyato B., Franquelo M., et al. (2001) Clinical aspects and prognostic factors in elderly patients hospitalised for community-acquired pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 20: 14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho J., Chan K., Hu W., Lam W., Zheng L., Tipoe G., et al. (2001) The effect of aging on nasal mucociliary clearance, beat frequency, and ultrastructure of respiratory cilia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163: 983–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huss A., Scott P., Stuck A., Trotter C., Egger M. (2009) Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 180: 48–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M., Nelson J., Jackson L. (2009) Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc 57: 882–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L., Gurtman A., Rice K., Pauksens K., Greenberg R., Jones T., et al. (2013) Immunogenicity and safety of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults 70 years of age and older previously vaccinated with 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Vaccine 31: 3585–3593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens J., Gauthey L., Herrmann F., Tkatch L., Michel J. (1996) Community-acquired pneumonia in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 44: 539–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens P., Krause K. (2004) Pneumonia in the very old. Lancet Infect Dis 4: 112–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson T., Di Pietrantonj C., Rivetti A., Bawazeer G., Al-Ansary L., Ferroni E. (2010) Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7: CD001269–CD001269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R., Sader H., Moet G., Farrell D. (2010) Declining antimicrobial susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1998–2009). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 68: 334–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juthani-Mehta M., De Rekeneire N., Allore H., Chen S., O’Leary J., Bauer D., et al. (2013) Modifiable risk factors for pneumonia requiring hospitalization of community-dwelling older adults: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. JAGS 61: 1111–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan V., Angus D., Griffin M., Clermont G., Scott Watson R., Linde-Zwirble W. (2002) Hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: age- and sex-related patterns of care and outcome in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 766–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keipp Talbo H., Falsey A. (2010) The diagnosis of viral respiratory disease in older adults. Clin Infect Dis 50: 747–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly E., MacRedmond R., Cullen G., Greene C., McElvaney N., O'Neill S. (2009) Community-acquired pneumonia in older patients: does age influence systemic cytokine levels in community-acquired pneumonia? Respirology 14: 210–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi R., Watabe N., Konno T., Mishina N., Sekizawa K., Sasaki H. (1994) High incidence of silent aspiration in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 150: 251–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Seo J., Mok J., Kim M., Cho W., Lee K., et al. (2013) Usefulness of plasma procalcitonin to predict severity in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Tuberc Respir Dis 74: 207–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausen H., Petersen J., Lindhardt T., Bandholm T., Hendriksen C., Kehlet H., et al. (2012) Outcomes in elderly Danish citizens admitted with community-acquired pneumonia. Regional differences, in a public healthcare system. Respir Med 106: 1778–1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothe H., Bauer T., Marre R., Suttorp N., Welte T., Dalhoff K. (2008) Outcome of community-acquired pneumonia: influence of age, residence status and antimicrobial treatment. Eur Respir J 32: 139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne F., Garant M., Carvalho J., Lanthier L., Smieja M., Pilon D. (2008) Pneumococcal vaccination and risk of myocardial infarction. CMAJ 179: 773–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim W., Macfarlane J. (2001) Defining prognostic factors in the elderly with community acquired pneumonia: a case controlled study of patients aged ≥75 yrs. Eur Respir J 17: 200–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim W., van der Eerden M., Laing R., Boersma W., Karalus N., Town G., et al. (2003) Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax 58: 377–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhardt T., Klausen H., Christiansen C., Smith L., Pedersen J., Andersen O. (2013) Elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia are not treated according to current guidelines. Dan Med J 60: A4572–A4572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., Tang W., Woo J. (2011) Predictors of in-hospital mortality of older patients admitted for community-acquired pneumonia. Age Ageing 40: 736–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell L., Wunderink R., Anzueto A., Bartlett J., Campbell G., Dean N., et al. (2007) Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 44(Suppl. 2): S27–S72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marik P. (2001) Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med 344: 665–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marik P., Kaplan D. (2003) Aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia in the elderly. Chest 124: 328–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T., Taguchi O., Niederman M., Morser J., Kobayashi H., Kobayashi T., et al. (2010) Efficacy of 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine in preventing pneumonia and improving survival in nursing home residents: double blind, randomised and placebo controlled trial. BMJ 340: c1004–c1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May D., Kelly J., Mendlein J., Garbe P. (1991) Surveillance of major causes of hospitalization among the elderly, 1988. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 40: 7–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metlay J., Schulz R., Li Y., Singer D., Marrie T., Coley C., et al. (1997) Influence of age on symptoms at presentation in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 157: 1453–1459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. (2001) The role of immunity in susceptibility to respiratory infection in the aging lung. Respir Physiol 128: 23–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberley S., Holden J., Tatham D., Andrews R. (2013) Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1: CD000422–CD000422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myint P., Kamath A., Vowler S., Maisey D., Harrison B. (2006) Severity assessment criteria recommended by the British Thoracic Society (BTS) for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and older patients. Should SOAR (systolic blood pressure, oxygenation, age and respiratory rate) criteria be used in older people? A compilation study of two prospective cohorts. Age Ageing 35: 286–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito T., Suda T., Yasuda K., Yamada T., Todate A., Tsuchiya T., et al. (2006) A validation and potential modification of the pneumonia severity index in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Am Geriatr Soc 54: 1212–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupane B., Walter S., Krueger P., Marrie T., Loeb M. (2010) Predictors of inhospital mortality and re-hospitalization in older adults with community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr 10: 22–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol K., Nordin J., Mullooly J., Lask R., Fillbrandt K., Iwane M. (2003) Influenza vaccination and reduction in hospitalizations for cardiac disease and stroke among the elderly. N Engl J Med 348: 1322–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederman M. (1994) Empirical therapy of community-acquired pneumonia. Semin Respir Infect 9: 192–198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederman M., McCombs J., Unger A., Kumar A., Popovian R. (1998) The cost of treating community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Ther 20: 820–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa-Gondar O., Vila-Córcoles A., de Diego C., Arija V., Maxenchs M., Grive M., et al. (2008) The burden of community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: the Spanish EVAN-65 study. BMC Public Health 8: 222–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa Gondar O., Vila Córcoles A., Rodriguez Blanco T., de Diego Cabanes C., Salsench Serrano E., Hospital Guardiola I. (2013) Ability of the modified CRB75 severity scale in assessing elderly patients with community acquired pneumonia. Aten Primaria 45: 208–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshitani Y., Nagai H., Matsui H. (2013) Rationale for physicians to propose do-not-resuscitate orders in elderly community-acquired pneumonia cases. Geriatr Gerontol Int.. DOI: 10.1111/ggi.12054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polverino E., Dambrava P., Cillóniz C., Balasso V., Marcos M., Esquinas C., et al. (2010) Nursing home-acquired pneumonia: a 10 year single-centre experience. Thorax 65: 354–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rello J., Rodriguez R., Jubert P., Alvarez B. (1996) Severe community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: epidemiology and prognosis. Study Group for Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 23: 723–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw M., Rockwell J., Engleman C., Gewirtz A., Katz J., Sambhara S. (2002) Cutting edge: impaired Toll-like receptor expression and function in aging. J Immunol 169: 4697–4701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme R., Torres A., El-Ebiary M., de la Bellacasa J., Estruch R., Mensa J., et al. (1996) Community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: a multivariate analysis of risk and prognostic factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 154: 1450–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme R., Torres A., el-Ebiary M., Mensa J., Estruch R., Ruiz M., et al. (1997) Community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Clinical and nutritional aspects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156: 1908–1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skull S., Andrews R., Byrnes G., Campbell D., Kelly H., Brown G., et al. (2009) Hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: an Australian case-cohort study. Epidemiol Infect 137: 194–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto S., Fukuchi Y., Sasaki H., Sato K., Sekizawa K., Matsuse T. (2008) High incidence of aspiration pneumonia in community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized patients: a multicenter, prospective study in Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc 56: 577–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiem U., Heppner H., Pientka L. (2011) Elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia: optimal treatment strategies. Drugs Aging 28: 519–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiem U., Niklaus D., Sehlhoff B., Stückle C., Heppner H., Endres H., et al. (2009) C-reactive protein, severity of pneumonia and mortality in elderly, hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Age Ageing 38: 693–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy J., Logemann J., Kahrilas P., Jacob P., Kobara M., Krugler C. (1989) Preliminary observations on the effects of age on oropharyngeal deglutition. Dysphagia 4: 90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifirò G., Gambassi G., Sen E., Caputi A., Bagnardi V., Brea J., et al. (2010) Association of community-acquired pneumonia with antipsychotic drug use in elderly patients: a nested case-control study. Ann Intern Med 152: 418–425, W139-W140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchiarino P., Bohannon R., Ferullo J., Maljanian R. (2004) Short-term outcomes and their predictors for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Heart Lung 33: 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viasus D., Cordero E., Rodríguez-Baño J., Oteo J., Fernández-Navarro A., Ortega L., et al. (2012) Changes in epidemiology, clinical features and severity of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 pneumonia in the first post-pandemic influenza season. Clin Microbiol Infect 18: E55–E62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viasus D., Paño-Pardo J., Pachón J., Campins A., López-Medrano F., Villoslada A., et al. (2011) Factors associated with severe disease in hospitalized adults with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect 17: 738–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila Córcoles A., Ochoa Gondar O., Rodríguez Blanco T. (2010) Usefulness of the CRB-65 scale for prognosis assessment of patients 65 years or older with community-acquired pneumonia. Med Clin (Barc) 135: 97–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Corcoles A., Ochoa-Gondar O., Rodriguez-Blanco T., Raga-Luria X., Gomez-Bertomeu F. (2009) Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia in older adults: a population-based study. Respir Med 103: 309–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J., Ho S., Mak Y., Law L., Cheung A. (1994) Nutritional status of elderly patients during recovery from chest infection and the role of nutritional supplementation assessed by a prospective randomized single-blind trial. Age Ageing 23: 40–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhead M., Blasi F., Ewig S., Garau J., Huchon G., Ieven M., et al. (2011) Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections - full version. Clin Microbiol Infect 17(Suppl. 6): E1–E59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalacain R., Torres A., Celis R., Blanquer J., Aspa J., Esteban L., et al. (2003) Community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: Spanish multicentre study. Eur Respir J 21: 294–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]