Obesity has emerged as a major health problem in the developed world and has been found to be associated with several respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological and digestive diseases. Few studies have investigated esophageal dysmotility in obese populations; however, they have reported conflicting results, primarily due to varying measures and classification systems. This prospective study aimed to determine the prevalence of esophageal motor disorders in a group of obese patients in Montreal, Quebec.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, Esophageal manometry, Obesity

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Obesity is an important health problem affecting >500 million people worldwide. Esophageal dysmotility is a gastrointestinal pathology associated with obesity; however, its prevalence and characteristics remain unclear. Esophageal dysmotilities have a high prevalence among obese patients regardless of gastrointestinal symptoms.

OBJECTIVE:

To identify the prevalence of esophageal dysmotility among obese patients. The secondary goals were to characterize these pathologies in obese patients and identify risk factors.

METHOD:

A prospective study from January 2009 to March 2010 at the University of Montreal Hospital Centre (Montreal, Quebec) was performed. Every patient scheduled for bariatric surgery underwent preoperatory esophageal manometry and was included in the study. Manometry was performed according to a standardized protocol with the following measures: superior esophageal sphincter – coordination and release during deglutition; esophageal body – presence, propagation, length, amplitude and type of esophageal waves of contraction; lower esophageal sphincter – localization, tone, release, intragastic pressure and intraesophageal pressure. All reference values were those used in the digestive motility laboratory. A gastrointestinal symptoms questionnaire was completed on the day manometry was performed. Chart reviews were performed to identify comorbidities and treatments that could influence the results.

RESULTS:

A total of 53 patients were included (mean [± SD] age 43±10 years; mean body mass index 46±7 kg/m2; 70% female). Esophageal manometry revealed dysmotility in 51% (n=27) of the patients. This dysmotility involved the esophageal body in 74% (n=20) of the patients and the inferior sphincter in 11% (n=3). Mixed dysmotility (body and inferior sphincter) was found in 15% (n=4) of cases. The esophageal body dysmotilities were hypomotility in 85% (n=23) of the patients, either from insignificant waves (74% [n=20]), nonpropagated waves (11% [n=3]) or low-amplitude waves (33% [n=9]). Gastroesophageal symptoms were found in 66% (n=35) of obese patients, including heartburn (66% [n=23]), regurgitation (26% [n=9]), dysphagia (43% [n=15]), chest pain (6% [n=2]) and dyspepsia (26% [n=9]). Among symptomatic patients, 51% (n=18) had normal manometry and 49% (n=17) had abnormal manometry (statistically nonsignificant). Among asymptomatic patients (n=18), 44% (n=8) had normal manometry and 56% (n=10) had abnormal manometry (statistically nonsignificant). Furthermore, no statistical differences were found between the normal manometry group and the abnormal manometry group with regard to medication intake or comorbidities.

CONCLUSION:

Esophageal dysmotilities had a high prevalence in obese patients. Gastrointestinal symptoms cannot predict the presence of esophageal dysmotility. Hypomotility of the esophageal body is the most common dysmotility, especially from the absence of significant waves.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

L’obésité est un problème de santé important qui touche plus de 500 millions de personnes dans le monde. La dysmotilité œsophagienne est une pathologie gastro-intestinale associée à l’obésité, mais on n’en connaît pas encore la prévalence et les caractéristiques exactes. La prévalence est élevée chez les patients obèses, quels que soient leurs symptômes gastro-intestinaux.

OBJECTIF :

Déterminer la prévalence de dysmotilité œsophagienne chez les patients obèses. Les objectifs secondaires consistaient à caractériser ces pathologies chez les patients obèses et à établir leurs facteurs de risque.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont mené une étude prospective de janvier 2009 à mars 2010 au Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, au Québec. Chaque patient devant subir une chirurgie bariatrique s’est soumis à une manométrie œsophagienne préopératoire et a été inclus dans l’étude. La manométrie a été effectuée selon un protocole standardisé faisant appel aux mesures suivantes : le sphincter œsophagien supérieur (coordination et relâchement pendant la déglutition), le corps de l’œsophage (présence, propagation, longueur, amplitude et type d’ondes de contraction de l’œsophage), sphincter inférieur de l’œsophage (emplacement, tonus, relâchement, pression intragastrique et pression intra- œsophagienne). Toutes les valeurs de référence sont celles utilisées au laboratoire de motilité digestive. Les patients ont rempli un questionnaire sur les symptômes gastro-intestinaux le jour de la manométrie. Les chercheurs ont examiné les dossiers pour déterminer les comorbidités et les traitements susceptibles d’influer sur les résultats.

RÉSULTATS :

Au total, 53 patients ont participé à l’étude (âge moyen [±ÉT] de 43±10 ans; indice de masse corporelle moyen de 46±7 kg/m2; 70 % de femmes). La manométrie de l’œsophage a révélé une dysmotilité chez 51 % (n=27) des patients. Cette dysmotilité touchait le corps de l’œsophage chez 74 % des patients (n=20) et le sphincter inférieur chez 11 % d’entre eux (n=3). Une dysmotilité mixte (corps et sphincter inférieur) a été observée dans 15 % des cas (n=4). Les dysmotilités du corps de l’œsophage s’expliquaient par une hypomotilité chez 85 % des patients (n=23), causée par des ondes insignifiantes (74 % [n=20]), des ondes non propagées (11 % [n=3]) ou des ondes de faible amplitude (33 % [n=9]). Des symptômes gastro-œsophagiens ont été constatés chez 66 % des patients obèses (n=35), y compris les brûlures d’estomac (66 % [n=23]), la régurgitation (26 % [n=9]), la dysphagie (43 % [n=15]), les douleurs thoraciques (6 % [n=2]) et la dyspepsie (26 % [n=9]). Chez les patients symptomatiques, 51 % (n=18) présentaient une manométrie normale et 49 % (n=17), une manométrie anormale (statistiquement non significative). Chez les patients asymptomatiques (n=18), 44 % (n=8) avaient une manométrie normale et 56 % (n=10), une manométrie anormale (statistiquement non significative). De plus, il n’y avait pas de différences statistiques entre le groupe ayant une manométrie normale et celui ayant une manométrie anormale en matière de prise de médicaments ou de comorbidités.

CONCLUSION :

La prévalence des dysmotilités œsophagiennes est élevée chez les patients obèses. Les symptômes gastro-intestinaux ne peuvent pas présager de la présence d’une dysmotilité œsophagienne. L’hypomotilité du corps de l’œsophage est la principale dysmotilité, causée notamment par l’absence d’ondes importantes.

Obesity is a major health problem that affects >500 million people worldwide (1). Many metabolic, cardiovascular, respiratory, locomotor and digestive diseases are associated with obesity (2,3). In the gastrointestinal system, obesity is a recognized risk factor for colorectal cancer, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hiatal hernia, gallstones and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. In addition, gastrointestinal motility disorders have also been described in the obese population. Three studies investigating esophageal motility in obese patients have reported conflicting results (4–6). Unfortunately, the measures used and classification methods are not comparable among studies. Consequently, the characteristics and prevalence of the esophageal motility disorder are unknown. Furthermore, obesity-associated comorbidities, such as diabetes (7), gastroesophageal reflux disease (8,9) and the drugs the patients take, are all confounding factors that may induce esophageal dysmotility and, thus, disrupt the cause-and-effect relationship.

The medical management of obesity is complex and multidisciplinary (10). Bariatric surgery is a treatment currently offered to patients (11,12). Most methods affect the stomach and aim to reduce its loading capacity, causing either early satiety or malabsorption (13,14). Dysphagia is a frequent postoperative complication and occurs especially with gastric banding (15). It is an extremely disabling symptom, sometimes painful and sometimes associated with belching disorders or an inability to vomit. The patients can experience such significant deterioration in their quality of life that, at times, surgical correction is necessary (16).

The presence of esophageal motility disorders before surgery can be associated with postoperative dysphagia. Some motility disorders can also precede surgery and, thus, be exacerbated postoperatively (17). Moreover, several surgeons require preoperative manometry for their patients to prevent these complications (18). In our centre, esophageal manometry is routinely performed before each gastric banding surgery for obesity.

We hypothesized that esophageal motility disorders are highly prevalent among obese patients. The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence of esophageal motor disorders in obese patients. Our secondary goals were to characterize these esophageal motor disorders and to identify associated clinical risk factors.

METHODS

A prospective study spanning January 2009 to March 2010 was conducted at the University of Montreal Hospital Centre (Montreal, Quebec). The study obtained approval from the institutional Research Ethics Committee.

Patients were followed in the obesity clinic by one bariatric surgeon. Once they were scheduled for surgery, patients were referred to the gastrointestinal motility laboratory for preoperative esophageal manometry.

Patients

Every patient scheduled for bariatric surgery underwent a preoperatory esophageal manometry and was included in the study. The inclusion criteria were: at least 17 years of age; a body mass index >29 kg/m2; and the ability to undergo esophageal manometry. The exclusion criteria included inability to sign the consent protocol, refusing to undergo manometry or to complete the questionnaire.

Manometry

Manometry was performed according to a standardized protocol. Stationary low-compliance perfusion manometry was performed using a round, four-lumen catheter. The data were downloaded for analysis into a specifically designed software program (Gastrosoft, Synectics Medical, Sweden). Lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure measurements were made using the four distal openings of the catheter and a recording speed of 2.5 mm/s. The tip of the catheter was positioned in the stomach and then slowly withdrawn in 1.0 cm increments. LES pressure was recorded at mid-expiration and end-expiration. Values were given as the mean of the three pressure channel readings. Contractions of the esophagus were recorded with the four pressure channels positioned 5 cm, 10 cm, 15 cm and 20 cm above the LES. Then, 10 swallows of 2 mL were given at 30 s intervals. The measurement of each peristaltic parameter represented the mean of the 10 sequential swallows, and both amplitude and duration were individually determined for the different recording site above the LES. The measures studied were: superior esophageal sphincter – coordination and release during deglutition; esophageal body – presence, propagation, length, amplitude and type of esophageal waves of contraction; and LES – localization, tone, release, the intragastic pressure and the intra-esophageal pressure. All reference values were those used in the digestive motility laboratory (19). The data analysis was performed by a gastroenterologist specialized in motility who did not perform the examination. The analysis of the manometry data enabled identification of two groups (ie, those with and without esophageal dysmotilities). The epidemiological data, prescription medication use and comorbidities between these two groups were compared.

Questionnaire

A symptoms questionnaire was completed on the day manometry was performed. Symptoms queried were heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia, chest pain and dyspepsia. A chart review was undertaken to identify the drugs and comorbidities that could influence the results. The most relevant comorbidities were diabetes, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, polymyositis, scleroderma, previous bariatric surgery and hiatal hernia. In terms of prescription medications, metoclopramide, domperidone, erythromycin, cisapride, proton pump inhibitors, antihistamines, calcium channel blockers, anticholinergics, opioids and sildenafil were most relevant. Telephone calls to patients were made when the charts were incomplete.

Statistics and analysis

Statistics and analysis involved calculating means and SDs. The Student’s t test and the χ2 test were used to compare data and generate P values; P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

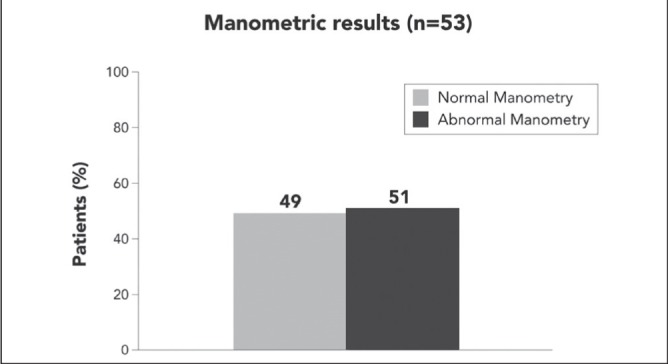

Fifty-three patients were included in the present study. The manometry performed on all patients was technically successful and interpretable. The mean (± SD) age of the patients was 43±10 years, the mean body mass index was 46±7 kg/m2 and 70% of the population was female. Proton-pump inhibitors were taken by 38% (n=20) of patients while 11% (n=6) were taking calcium channel inhibitors. With regard to comorbidities, 21% of patients (n=11) were diabetic, 11% (n=6) had hypothyroidism, 15% (n=8) had already undergone unsuccessful bariatric surgery and 15% (n=8) had hiatal hernia. Gastroesophageal symptoms were reported by 66% (n=35) of obese patients including heartburn (66% [n=23]), regurgitation (26% [n=9]), dysphagia (43% [n=15]), chest pain (6% [n=2]) and dyspepsia (26% [n=9]). Forty-nine percent of patients (n=26) had normal manometry while slightly more than one-half (51%) had abnormal manometry (n=27) (Figure 1). Epidemiological data, comorbidities, medications, and symptoms of patients with and without dysmotility are reported in Table 1. There were no significant differences with regard to the presence of comorbidities between the two groups, including hiatal hernia. Regurgitation was the only symptom with higher reported frequency in patients with abnormal manometry (n=7) than in those with normal manometry (n=2) (Table 1). Anomaly types at esophageal manometry were not statistically significant.

Figure 1).

Abnormal manometry in obese patients

TABLE 1.

Comparison of clinical characteristics between patients with normal and abnormal manometry

| Characteristic | Manometry | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Normal (n=26) | Abnormal (n=27) | ||

| Epidemiological data | |||

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 43±9 | 44±11 | NS |

| Female sex | 16 (62) | 21 (78) | NS |

| Weight, kg, mean ± SD | 130±24 | 127±18 | NS |

| Height, cm, mean ± SD | 166±9 | 167±10 | NS |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 47±7 | 45±6 | NS |

| Medication | |||

| Metoclopramide | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Domperidone | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Erythromycin | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Cisapride | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 9 (35) | 11 (41) | NS |

| Anti-H2 | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Calcium channel blocker | 3 (12) | 3 (11) | NS |

| Anticholinergic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Opioid | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | NS |

| Sildenafil | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 8 (31) | 3 (11) | NS |

| Hypothyroidism | 3 (12) | 3 (11) | NS |

| Hyperthyroidism | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Scleroderma | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Polymyositis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Bariatric surgery | 5 (19) | 3 (11) | NS |

| Hiatal hernia | 4 (15) | 4 (15) | NS |

| Symptoms | |||

| Pyrosis | 13 (50) | 10 (37) | NS |

| Regurgitation | 2 (8) | 7 (26) | 0.04 |

| Dysphagia | 7 (27) | 8 (30) | NS |

| Chest pain | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Dyspepsia | 4 (15) | 5 (19) | NS |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated. BMI Body mass index; NS Not statistically significant

In the group with abnormal esophageal manometry, dysmotility involved the esophageal body in 74% (n=20) of the patients and the inferior sphincter in 11% (n=3). A mixed dysmotility (body and inferior sphincter) was found in 15% (n=4) of cases. The superior sphincter was preserved. The esophageal body dysmotilities were hypomotility in 85% (n=23), either from insignificant waves (74% [n=20]), nonpropagated waves (11% [n=3]) or low amplitude waves (33% [n=9]). The inferior sphincter presented mostly an incomplete release (15% [n=4]) and hypotonia (7% [n=2]) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Anomaly types in the abnormal esophageal manometry group (n=27)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Superior esophageal sphincter | 0 (0) |

| Release | 0 (0) |

| Coordination | 0 (0) |

| Esophageal body | 24 (89) |

| Ineffective waves ≤30 mmHg (≥20%) | 20 (74) |

| Unpropagated waves (≥20%) | 3 (11) |

| Low amplitude (≤40 mmHg) | 9 (33) |

| High amplitude (≥180 mmHg) | 1 (4) |

| Lower esophageal sphincter | 7 (26) |

| Hypotonia (≤10 mmHg) | 2 (7) |

| Hypertonia (≥45 mmHg) | 1 (4) |

| Incomplete release | 4 (15) |

DISCUSSION

In the present study, 51% of obese patients showed esophageal dysmotilities at manometry. This mainly involved the esophageal body and, more specifically, hypomotility. The upper esophageal sphincter was intact and a minority of patients had LES dysfunction.

Few studies have characterized esophageal dysfunction in an obese population to obtain a prevalence estimate of this condition. In one study, Jaffin et al (4) reported that 61% of the obese population had an esophageal motility dosorder, the majority of whom had an incompetent lower esophageal sphincter. In another study, Koppman et al (5) found that 41% of the obese population had esophageal dysmotility. Most of cases met the diagnostic criteria of nonspecific esophageal motility disorders, consisting principally of esophageal body hypomotility (20). According to a study by Suter et al (6), 25% of obese patients had esophageal dysmotility and most had an incompetent LES.

Despite the differences in methodologies and results of these studies, they commonly report a high prevalence of esophageal dysmotility according to manometry in obese patients. To determine the prevalence in a normal population, we must refer to studies that established the normal values for manometry. In 1987, Richter et al (21) established normal manometric values by performing esophageal manometry in 95 normal subjects. Normal values were obtained by calculating the mean ± 2 SDs. Thus, in a normal population, we should find an esophageal dysmotility prevalence of 5%.

In our study, we report mostly esophageal body hypomotility. The explanation for this observation remains unknown and further studies are needed. Gastroesophageal reflux disease is known to cause dysmotility in the esophageal body and its prevalence in the obese population is high (22). However, in our study, no statistical difference was found between normal and abnormal manometry groups with regard to pyrosis, a classical symptom of gastroesophageal reflux. In contrast, regurgitation was highly reported in the abnormal manometry group, although a significant correlation was not found between regurgitation and manometry anomaly type. Moreover, the low prevalence of that symptom render the cause-and-effect relationship unlikely.

We believe that leptin may play an important role in the phenomenon (23,24). Leptin is a hormone derived from adipose tissue that acts by modulating appetite and energy control. Leptin concentration varies with age, sex, weight and the time of day (25). High leptin levels have been shown to modulate the energy balance in the obese population (26). Leptin receptors are found in afferent and efferent endings of the vagus nerve, modulating gastrointestinal motility. According to Yarandi et al (23), leptin decreases gastric and intestinal motility. We hypothesize that a similar phenomenon may occur in the esophagus.

Because the data were available, we compared the normal manometry group and abnormal manometry group with regard to epidemiological data, comorbidities and medications. Our results showed no significant differences between groups with regard to these factors. In contrast, given that the diagnosis of diabetes was obtained from the chart review and not from objective measures, an underestimation of diabetes probably occurred in our cohort. However, we do not believe it would significantly alter our findings.

We also demonstrated that no correlation was present between gastroesophageal symptoms and esophageal manometry results. As described in various studies (6–27), we believe that dysfunction in visceral sensitivity would be present in obese patients.

CONCLUSION

The present study revealed a high prevalence of esophageal dysmotility in obese patients (51%). Hypomotility of the esophageal body was the most frequently observed anomaly, particularly the lack of effective peristaltic waves. No correlation was observed with regard to epidemiological data, comorbidities and medications between normal and abnormal manometry groups. Finally, gastrointestinal symptoms did not predict the results of manometry, suggesting an abnormality in visceral sensitivity in obese patients.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) < www.who.int/topics/obesity/en> (Accessed November 2, 2013).

- 2.Nguyen NT, Magno CP, Lane KT, et al. Association of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome with obesity: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:928–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collaboration PS, Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: Collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. 2009;373:1083–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffin BW, Knoepflmacher P, Greenstein R. High prevalence of asymptomatic motility disorders among morbidly obese patients. Obesity. 1999;9:390–5. doi: 10.1381/096089299765552990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koppman JS, Poggi L, Szomstein S, et al. Esophageal motility disorders in the morbidly obese population. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:761–4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9102-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suter M, Dorta G, Giusti V, et al. Gastro-esophageal reflux and esophageal motility disorders in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2004;14:959–66. doi: 10.1381/0960892041719581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao J, Frøkjaer JB, Drewes AM, et al. Upper gastrointestinal sensory-motor dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2846–57. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i18.2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand G, Katz PO. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity. Gastroenterol Clinics N Am. 2010;39:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisichella PM, Patti MG. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and morbid obesity: Is there a relation? World J Surg. 2009;33:2034–8. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0045-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth J, Qiang X, Marbán SL, et al. The obesity pandemic: Where have we been and where are we going? Obes Res. 2004;(12 Suppl 2):88S–101S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Favretti F, Ashton D, Busetto L, et al. The gastric band: First-choice procedure for obesity surgery. World J Surg. 2009;33:2039–48. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien PE, Dixon JB, Brown W. Obesity is a surgical disease: Overview of obesity and bariatric surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:200–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2004.03014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan JL, Mun EC, Stoyneva V, et al. Peptide YY levels are elevated after gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:194–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prachand VN, Alverdy JC. The role of malabsorption in bariatric surgery. World J Surg. 2009;33:1989–94. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burton PR, Brown W, Laurie C, et al. Outcomes, satiety, and adverse upper gastrointestinal symptoms following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2011;21:574–81. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roller JE, Provost DA. Revision of failed gastric restrictive operations to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: Impact of multiple prior bariatric operations on outcome. Obes Surg. 2006;16:865–9. doi: 10.1381/096089206777822412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suter M, Giusti V, Calmes JM, Paroz A. Preoperative upper gastrointestinal testing can help predicting long-term outcome after gastric banding for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2008;18:578–82. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klaus A, Weiss H. Is preoperative manometry in restrictive bariatric procedures necessary? Obes Surg. 2008;18:1039–42. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9399-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Committee, AGA Technical Review on the Clinical Use of Esophageal Manometry. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:209–24. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leite LP, Johnston BT, Barrett J, et al. Ineffective esophageal motility (IEM): The primary finding in patients with nonspecific esophageal motility disorder. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1859–65. doi: 10.1023/a:1018802908358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richter JE, Wu WC, Johns DN, et al. Esophageal manometry in 95 healthy adult volunteers. Variability of pressures with age and frequency of “abnormal” contractions. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:583–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01296157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quiroga E, Flum D, Dellinger EP, Oelschlager BK. Impaired esophageal function in morbidly obese patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: Evaluation with multichannel intraluminal impedance. Surg Endosc. 2006:739–43. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yarandi SS, Hebbar G, Sauer CG, et al. Diverse roles of leptin in the gastrointestinal tract: Modulation of motility, absorption, growth, and inflammation. Nutrition (Burbank) 2011;27:269–75. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hata N, Murata S, Maeda J, et al. Predictors of gastric myoelectrical activity in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:429–36. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818337f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Z, Gingerich RL, Santiago JV, Klein S, Smith CH, Landt M. Radioimmunoassay of leptin in human plasma. Clin Chem. 1996;42:942–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saad MF, Riad-Gabriel MG, Khan A, et al. Diurnal and ultradian rhythmicity of plasma leptin: Effects of gender and adiposity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:453. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.2.4532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Küper MA, Kramer KM, Kirschniak A, et al. Dysfunction of the lower esophageal sphincter and dysmotility of the tubular esophagus in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1143–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9881-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]