Summary

GABA release from interneurons in VTA, projections from the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg) was selectively activated in rat brain slices. The inhibition induced by μ-opioid agonists was pathway dependent. Morphine induced a 46% inhibition of IPSCs evoked from the RMTg, 18% from NAc and IPSCs evoked from VTA interneurons were almost insensitive (11% inhibition). In vivo morphine treatment resulted in tolerance to the inhibition of RMTg inputs, but not local interneurons or NAc inputs. One common sign of opioid withdrawal is an increase in adenosine-dependent inhibition. IPSCs evoked from the NAc were potently inhibited by activation of presynaptic adenosine receptors, whereas IPSCs evoked from RMTg were not changed. Blockade of adenosine receptors selectively increased IPSCs evoked from the NAc during morphine withdrawal. Thus, the acute action of opioids, the development of tolerance, and the expression of withdrawal are mediated by separate GABA afferents to dopamine neurons.

Keywords: VTA, mu-opioid receptor, ChannelRhodopsin2, RMTg, interneurons, chronic morphine treatment, GABA-A

Introduction

Dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) respond by burst firing following salient stimuli, motivation or impulsive movement (Bromberg-Martin et al., 2010; Schultz, 2007). The rate and pattern of dopamine neuron firing is tightly controlled by the balance of intrinsic activity and synaptic input. The GABA input from areas including the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr), nucleus accumbens (NAc), ventral pallidum/globus pallidus, the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg), laterodorsal tegmentum, pedunculopontine nuclei and diagonal band of Broca, and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis make up at least 70% of synaptic input to dopamine neurons (Bolam and Smith, 1990; Charara et al., 1996; Kalivas et al., 1993; Omelchenko and Sesack, 2005; Tepper et al., 1995; Tepper and Lee, 2007; Watabe-Uchida et al., 2012). Tonic GABA input is sufficient to suppress burst firing even with excitatory inputs intact (Jalabert et al., 2011; Lobb et al., 2010). Thus, it is important to understand the mechanisms that modulate the release of GABA onto dopamine neurons.

GABA input to dopamine neurons is reduced by the activation of μ-opioid receptors (MORs), resulting in an increase in the firing rate of dopamine neurons originally thought to be mediated by local interneurons (Gysling and Wang, 1983; Johnson and North, 1992). Recently, neurons in the RMTg were found to send a dense opioid sensitive GABA input to dopamine neurons (Jhou et al., 2009; Kaufling et al., 2009), suggesting that the local interneurons may not be the major site of action of opioids (Jalabert et al., 2011). Additionally, projections from the NAc also synapse onto dopamine neurons (Cui et al., 2014; Kalivas et al., 1993; Watabe-Uchida et al., 2012) although that innervation is less dense than the innervation of GABA cells in the VTA (Bocklisch et al., 2013; Xia et al., 2011).

With repeated administration of opioids, tolerance, dependence and addiction can develop, driven through adaptive mechanisms initiated in the mesolimbic pathway. Cellular tolerance to opioids, determined by the reduction in efficacy, has been observed postsynaptically in multiple assays (Christie et al., 1987; Connor et al., 1999; Sim et al., 1996; Williams et al., 2013). On the other hand, opioid actions at presynaptic terminals following repeated morphine treatment has been reported to be increased or decreased in different brain areas such as the periaqueductal gray and arcuate nucleus (Fyfe et al., 2010; Hack et al., 2003; Ingram et al., 1998; Pennock and Hentges, 2011) including GABA terminals in teh VTA (Lowe and Bailey, 2014). One hallmark of the withdrawal from morphine is the development of a cAMP-dependent increase in the probability of GABA release in the VTA. The opioid sensitivity of GABA inputs from interneurons, the RMTg and the NAc has not been examined following chronic morphine treatment.

The present study examines GABA IPSCs on dopamine neurons evoked from three different afferent pathways: interneurons, the NAc and the RMTg. In order to activate GABA afferent pathways selectively, channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) was expressed in each region and blue light (473 nm) was used to initiate transmitter release. The inhibition of IPSCs by the opioid agonists [Met5]enkephalin, DAMGO, and morphine was examined in each pathway in slices taken from untreated and morphine treated animals (MTAs). The results show projection specific (1) sensitivity to opioids, (2) development of tolerance and (3) adenosine-dependent withdrawal.

Results

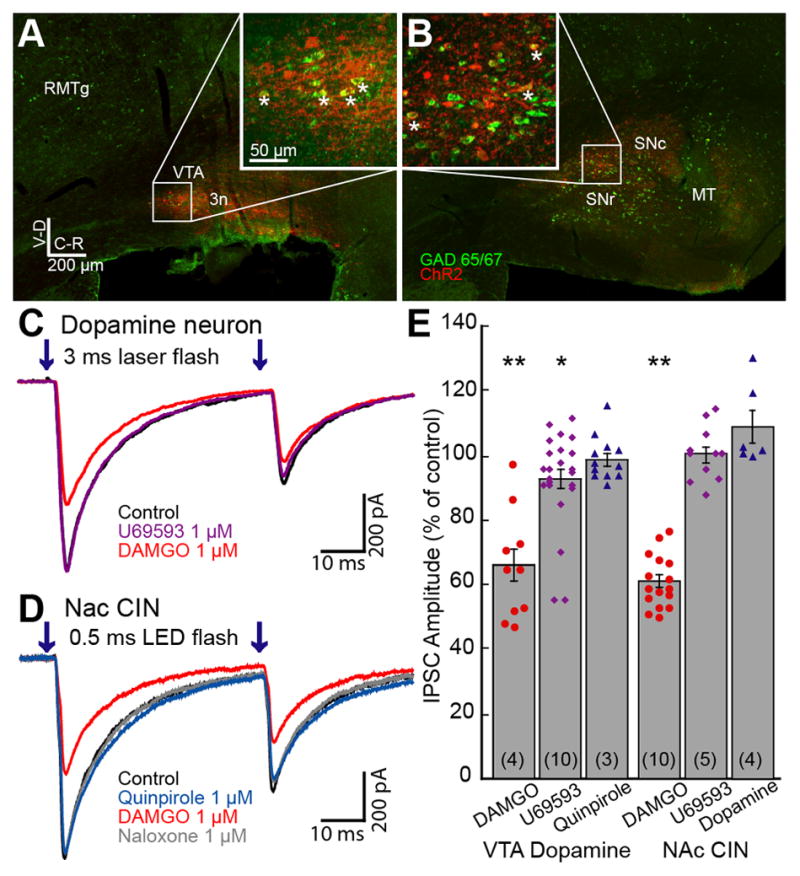

ChR2 expression in the VTA - dopamine and GABA neurons

Injection of AAV-DJ (100 nl, AAV-CAG-ChR2-Venus) resulted in the expression of ChR2 that was limited to small regions of the VTA and substantia nigra (SN, Figure 1A,B). Fluorescent in situ hybridization was used to detect mRNA for GAD65 and GAD67 (Jarvie and Hentges, 2012), the enzymes responsible for GABA synthesis. Gad65/67 expression was found in areas known to contain GABA neurons, including the VTA and SN. The number of neurons that expressed ChR2 was counted from 6 injection sites from 3 animals. Of the ChR2-positive neurons in both the VTA and SN, 21.7% expressed Gad65/Gad67 mRNA (Figure 1A,B; 418/1924 neurons, n=6 injections). Previous reports indicated that approximately 30–35% of VTA and 20% of SNc neurons are GABAergic (Dobi et al., 2010; Nair-Roberts et al., 2008; Van Bockstaele and Pickel, 1995). Thus ChR2 was expressed in both GABA and non-GABA neurons in the VTA and SN. Given the heterogeneity of neurons in the SNc and VTA, ChR2 expression in non-GABA neurons is most likely in both dopamine and glutamate neurons (Yamaguchi et al., 2011). Differences between the cellular properties of glutamate and dopamine neurons in the VTA have not been identified, with the possible exception of the projections to the medial prefrontal cortex that are insensitive to dopamine (Lammel et al., 2008). Neurons in the present study were considered to be dopamine neurons based on a combination of intrinsic properties and the sensitivity to dopamine as described previously (Chieng et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2006).

Figure 1. Opioids cause a small inhibition of GABA-A IPSCs originating from the VTA/SN.

Images of brain sections with Gad65/67 (Green) labeled by fluorescent in situ hybridization and ChR2 (Red) immunolabeled against Venus show GABA neurons within the VTA/SN that express ChR2. A. Medial sagittal slice of the midbrain containing the VTA. ChR2 expression was restricted within the VTA. Inset shows an enlarged view of the boxed area. Some cells showing colocalization of Gad65/67 and ChR2 are indicated with asterisks. B. Lateral sagittal slice containing the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and reticulata (SNr). ChR2 expression was observed in SNc and SNr. RMTg, rostromedial tegmental nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area; 3n, oculomotor nerve; MT, medial terminal nucleus of accessory optic tract. C. Superimposed traces of paired GABA-A IPSCs in a dopamine neuron. GABA-A IPSCs were inward because of the high chloride internal solution. D. Superimposed traces of IPSCs in a CIN. E. Summary graph of the inhibition of IPSCs in dopamine neurons and CINs. DAMGO (1 μM) significantly decreased IPSC amplitude to a similar extent in both neuronal populations. U69593 (1 μM) caused a small and significant inhibition of the IPSC amplitude in dopamine neurons, but not in CINs. Quinpirole or dopamine did not change the IPSC amplitude in either cell type. Results from individual experiments are shown as dots. In this and all other figures, the number in the parentheses indicates the total number of animals used in the particular experiment. Traces shown are averages of 5 sweeps. Error bars indicate SEM. *p< 0.05 and **p<0.001 by one-sample Student’s t test.

GABA-A IPSCs from interneurons in the VTA were sensitive to opioids

Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings were made from dopamine neurons and focal (20–100 μm diameter) laser stimulation (3 ms paired flashes; 50 ms apart) was applied every 30 seconds. All experiments were carried out in the presence of DNQX (10 μM) and MK801 (pretreated with 10 μM, 30min) to rule out possible interference resulting from the polysynaptic release of GABA. Activation of ChR2-expressing GABA interneurons in the VTA resulted in inward IPSCs induced by the activation of GABA-A receptors (ECl=−14 mV). In some cases, a small inward current was induced by the direct activation of ChR2 in the recorded neuron followed by a GABA-A IPSC. In such experiments, the direct ChR2 current was subtracted from GABA-A IPSCs post-hoc following the application of GABA-A receptor antagonist (picrotoxin, 100 μM or SR 95531, 3 μM). The ChR2-evoked GABA-A IPSCs were blocked with the sodium channel blocker TTX (300 nM), thus GABA-A IPSCs were dependent on presynaptic action potentials. Varying the duration of light stimulation (2–5 ms) did not affect the sensitivity to TTX. Application of a saturating concentration of the MOR-selective agonist, DAMGO (1 μM) significantly decreased the amplitude of IPSCs (66.0±5.3% of control, n=10, 4 animals, t9=6.47, p<0.001, Student’s t test; Figure 1C,E). To examine whether the opioid inhibition of GABA-A IPSCs was mediated by a presynaptic mechanism, the paired-pulse ratio (PPR = IPSC2/IPSC1) was measured. The PPR increased from 0.56±0.02 in control to 0.64±0.03 in the presence of DAMGO (n=10, t9=2.71, p<0.05), suggesting that the inhibition was the result of a presynaptic mechanism. The κ-opioid receptor (KOR) agonist, U69653 (1 μM), caused a very small inhibition of the GABA-A IPSC (92.7±3.1% of control, n=23, 10 animals, t22=2.36, p=0.03; Figure 1E) with no change in the PPR (n=23, t22=1.59, p=0.127).

Recently, dopamine neurons have been found to release GABA onto medium spiny neurons (MSNs) in mouse and the D2-like receptor agonist, quinpirole, inhibited that release (Tritsch et al., 2012). In the present study, dopamine (3–10 μM) or quinpirole (3 μM) failed to change the IPSC amplitude significantly (101.5±3.5% of control, n=5, 3 animals, t4=0.43, p=0.69; and 99.0±1.9% of control, n=12, 3 animals, t11=0.51, p=0.62, respectively; Figure 1E). There was no change in the PPR with either agonist (n=16, t16=0.93, p=0.37). Thus, the ChR2-induced GABA release was the result of the activation of interneurons that were sensitive to inhibition by MORs but not dopamine receptors.

Previous reports indicate that the GABA neurons in the VTA project to the NAc (Brown et al., 2012; Van Bockstaele and Pickel, 1995; van Zessen et al., 2012). ChR2 expression in the VTA resulted in light-evoked GABA-A IPSCs in the cholinergic interneurons (CINs) of the NAc (average amplitude 463±132 pA, n=34; Figure 1D). The MOR agonist, DAMGO (1 μM), significantly inhibited the IPSCs in CINs (61.4±2.0% of control, n=16, 10 animals, t15=19.12, p<0.001; Figure 1E), and increased the PPR (from 0.47±0.04 to 0.62±0.04, n=16, t15=4.56, p<0.0001, Student’s t test). As previously described, DAMGO (1 μM) also induced an outward current (109.8±24.68 pA, n=11; Britt and McGehee, 2008). The GABA IPSCs were insensitive to the KOR agonist U69593 (1 μM; 100.5±2.6% of control, n=11, 5 animals, t10=0.19, p=0.85) and dopamine (3 μM, 109.2±5.1% of control, n=6, t5=1.78, p=0.14; Figure 1E), suggesting that the IPSCs did not result from the activation of dopamine afferents. The inhibition of GABA-A IPSCs induced by DAMGO (1 μM) in CINs was similar in magnitude to the inhibition measured in dopamine neurons (61.4±2.0% of control in CINs vs 66.0±5.3% in dopamine neurons). Small amplitude GABA-A IPSCs were also observed in MSNs. GABA-A IPSCs in MSNs were significantly inhibited by the D2-like receptor agonist quinpirole (3 μM; 36.7±9.1% of control, n=5, 4 animals, p=0.002), but were not sensitive to the opioid agonist [Met5]enkephalin (ME, 1 μM; 99.5±3.8% of control, n=5, p=0.13). Thus, the GABA-input from the VTA/SN to MSNs is most likely from dopamine neurons as previously reported (Tritsch et al., 2012).

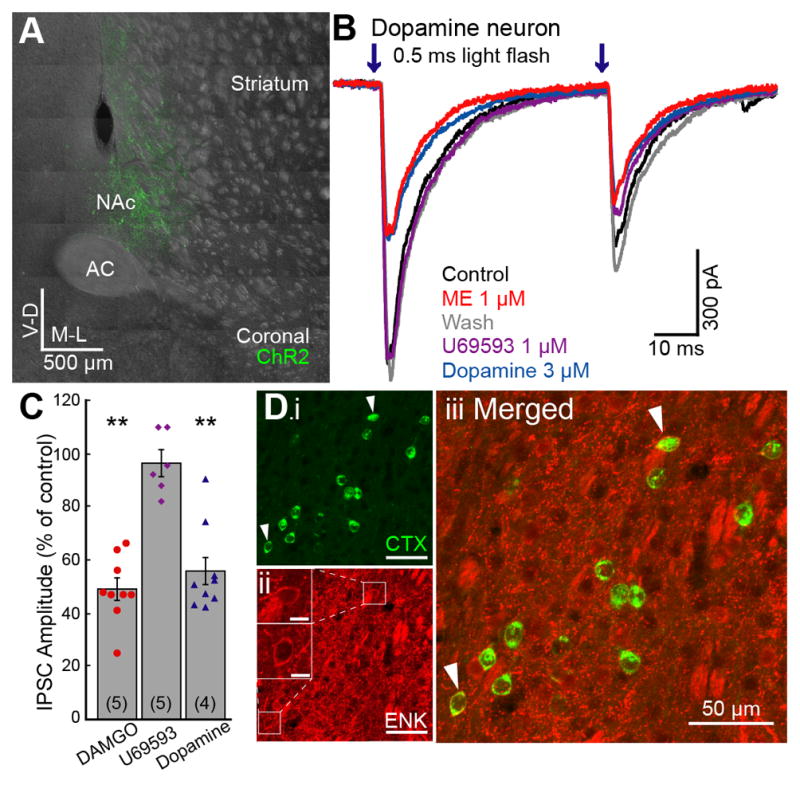

A direct D2-receptor-containing MOR-sensitive GABA input to DA neurons from the NAc

Recent studies have demonstrated that dopamine neurons receive GABA input from a specific subset of nucleus accumbens neurons (Bocklisch et al., 2013; Cui et al., 2014; Watabe-Uchida et al., 2012); however, the strength of these synaptic connections and the presynaptic receptors at those terminals remains controversial (Bocklisch et al., 2013; Chuhma et al., 2011; Xia et al., 2011). ChR2 was expressed in the NAc using a ubiquitous promoter (CAG) in an AAV-9 serotype (Figure 2A). Additional retrograde expression of ChR2 in dopamine neurons was observed in the midbrain 5 weeks after viral injection (data not shown). To avoid the activation of retrogradely labeled cells, experiments were performed within 4 weeks after injection. Full field LED light stimulation (1–5 ms duration paired stimuli; 50 ms interval; every 30 seconds) was applied to evoke GABA-A IPSCs in dopamine neurons. Although GABA-A IPSCs were frequently observed in GABA neurons in the VTA (data not shown), activation of ChR2 in terminals from the NAc also induced GABA-A IPSCs in some VTA dopamine neurons indicating that there is a functional connection between the NAc and VTA dopamine neurons (Figure 2B). The amplitude of GABA-A IPSCs in dopamine neurons was significantly decreased by the MOR agonists morphine (1 μM, 81.9±2.9% of control, n=9, 5 animals, t8=6.28, p=0.0002), and DAMGO (1 μM, 49.3±4.2% of control, n=9, 5 animals, t8=12.1, p<0.0001, Student’s t test); however, the KOR agonist U69593 (1 μM) did not alter the GABA-A IPSC amplitude (96.4±4.7% of control, n=6, 5 animals, t5=0.78, p=0.47; Figure 2C). In addition, dopamine (3 μM) also significantly decreased GABA-A IPSC amplitude (55.7±5.3% of control, n=9, 4 animals, t8=8.29, p<0.0001). This inhibition was mimicked with an application of D2-like receptor agonist quinpirole (3 μM, 39.1±9.0% of control, n=3, 3 animals). These results suggest that in the rat, a direct GABAergic input from the NAc to the VTA exists that is unlike the traditional direct pathway in the sensitivity to both MOR- and D2-receptor agonists and not KOR-agonists.

Figure 2. GABA projections from the NAc to dopamine neurons are inhibited by MORs.

ChR2 was expressed in the NAc and GABA-A IPSCs were recorded from dopamine neurons in the VTA. ChR2 was activated by paired LED flashes (0.5 ms; 50 ms interval; 473 nm). A. Coronal image of a brain section expressing ChR2 in the NAc (green). B. Representative traces showing the ME (1 μM) and dopamine (3 μM) induced inhibition of IPSCs in dopamine neurons. ME was used to test MOR sensitivity so that the sensitivity to subsequent application of U69593 could be observed. C. Summary graph of the inhibition of IPSCs in dopamine neurons and CINs. DAMGO (1 μM), and dopamine (3 μM) significantly inhibited IPSCs. U69593 (1 μM) had no effect. D. Coronal image of a NAc brain section showing retrograde tracer Cholera Toxin B (CTX) positive neurons (i: green) and enkephalin (ENK) immunopositive neurons (ii: red). Insets (ii) show ENK immunoreactivity of co-labeled neurons (arrowhead). Scale bar, 50 μm and 10 μm in insets. AC, anterior commissure; NAc, nucleus accumbens. Traces shown are averages of 5 sweeps. Error bars indicate SEM. **p<0.001 by one-sample Student’s t test.

These non-canonical GABA inputs were examined anatomically using the retrograde transport of fluorescent-cholera toxin B (CTX) from the VTA combined with immunohistochemical identification of neurons in the NAc. The traditional D2-expresing indirect pathway MSNs were identified as enkephalin positive neurons believed to also express MORs. The results show 10.8% of NAc neurons projecting directly to the VTA are enkephalin immunopositive (Figure 2D; 259/2438 cells, 6 injections, 3 animals). Although unexpected, the functional and anatomical results indicate the presence of this MOR sensitive pathway.

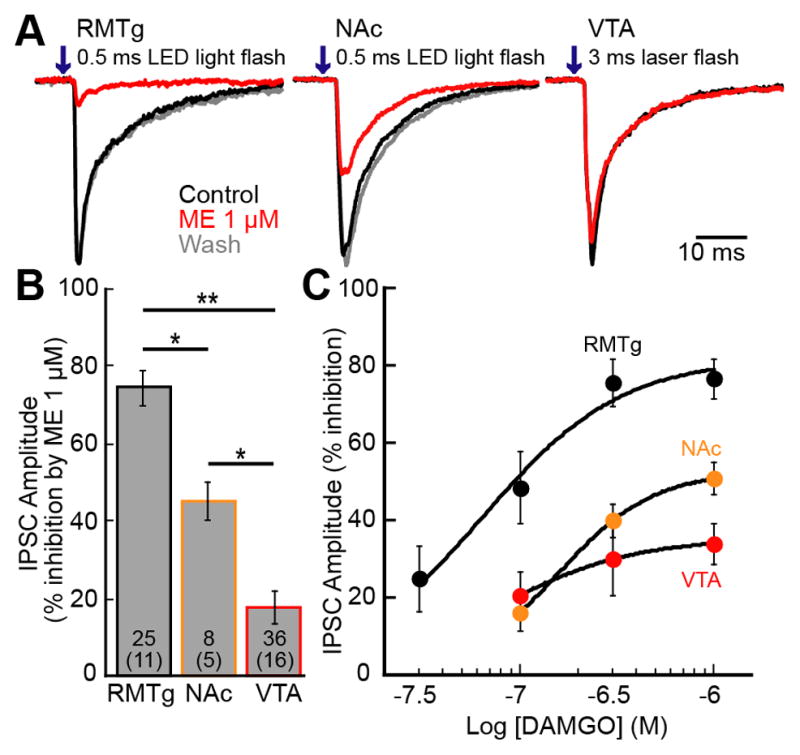

The RMTg is the major opioid-sensitive GABA input to DA neurons

The dense GABA input from the RMTg to dopamine neurons has been previously shown to be potently inhibited by opioids (Matsui and Williams, 2011). To determine the relative amount of inhibition from each GABA afferent, a sub-saturating concentration of ME (1 μM) was applied. The GABA-A IPSCs from the RMTg were decreased by 74.5±4.7% (n=25, 11 animals,), whereas inputs from the NAc and local VTA interneurons were inhibited only by 45.0±5.1% (n=8, 5 animals) and 17.4±4.2% (n=36, 16 animals), respectively (Figure 3A,B). Thus, the input from the RMTg was more strongly inhibited than those from the NAc or local interneurons (F(2,66)=43.0 p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA bonferroni). Since ME is not mu-receptor specific, receptor subtype and sensitivity of the different inputs was further characterized by using the selective agonist DAMGO to construct concentration-response curves for each of the GABA inputs (Figure 3C). The concentration-response curve for the RMTg input was adapted from a previous study (Matsui and Williams, 2011). The maximum inhibition of GABA-A IPSCs from the RMTg induced by DAMGO was 81.5±10.2% whereas the inhibition of the GABA-A IPSCs evoked from the NAc and VTA interneurons was 52.8±6.8% and 35.2±8.7%, respectively. The EC50 was similar for each of the GABA pathways (65 nM, 95% confidence interval (CI)=32–136 nM for RMTg; 163 nM, CI=90–293 nM for NAc; and 79 nM CI=21–297 nM for VTA). Thus, the potency of MOR-dependent inhibition of each GABA input did not differ, however, the maximum effect of DAMGO was very different. Thus, opioid inhibition of GABA-A IPSCs measured on dopamine neurons is largely due to terminals arising from the RMTg.

Figure 3. Opioid receptor inhibition of IPSCs from the RMTg, NAc and VTA.

ChR2 was expressed either in RMTg, NAc, or VTA neurons and GABA-A IPSCs were recorded from dopamine neurons. A. Representative traces of IPSCs from RMTg, NAc, or VTA inputs. B. Summary graph shows % inhibition of the IPSC by ME (1 μM) for each input. C. Concentration response curves of the inhibition of IPSCs by DAMGO. The concentration response curve from the RMTg was adapted from a previous paper (Matsui and Williams, 2011). RMTg (black), NAc (orange), and VTA (red) inputs were constructed by recording from dopamine neurons. Traces are the average of 5 sweeps. Error bars indicated SEM. *p< 0.05 and **p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA with bonferroni’s post-test.

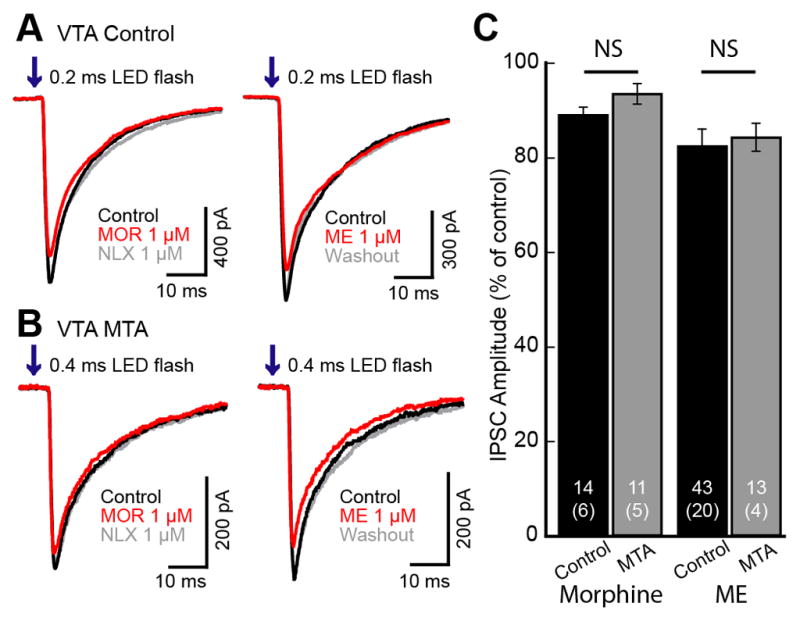

Limited tolerance from interneurons

The presynaptic inhibition of GABA release by opioids following chronic morphine treatment has been reported to vary depending on the synapse, differences in the downstream signaling pathways and treatment protocols (Fyfe et al., 2010; Hack et al., 2003; Ingram et al., 1998; Pennock and Hentges, 2011). The inhibition of GABA release onto dopamine neurons after chronic morphine treatment was examined from (1) interneurons of the VTA, (2) the RMTg, and (3) the NAc by expressing ChR2 in each area. Approximately 1–2 weeks after virus injection, osmotic mini pumps were implanted subcutaneously. Morphine was released (50 mg•kg−1•d−1) for a week. Brain slices were prepared in morphine-free ACSF and washed at least 2 hours to remove the residual morphine. Full field light stimulation (1–1.5 ms duration paired stimuli; 50 ms interval; every 30 seconds, LED) or focal laser stimulation (3 ms duration paired stimuli; 50 ms interval; every 30 seconds; 20–100 μm diameter) was applied to evoke GABA-A IPSCs in dopamine neurons. The opioid-induced inhibition of IPSCs evoked by each method was the same (p=0.48), so the results were pooled.

Application of morphine (1 μM) caused small but significant inhibition of GABA-A IPSCs evoked from VTA interneurons in control animals (88.9±1.6% of control, n=14, 6 animals, t13=6.83, p<0.001; Figure 4A, C) and morphine treated animals (MTAs, 93.3±2.2% of control, n=11, 5 animals, t10=3.05, p=0.01; Figure 4B, C). The inhibition induced by morphine was not significantly different between slices from untreated or morphine treated animals (t19=1.64, p=0.11). Since the inhibition by morphine was small, the sensitivity of IPSCs to ME, a more efficacious agonist was examined. This sub-saturating concentration of ME (1 μM) decreased the IPSC amplitude to 82.3±3.6% of baseline in slices from untreated animals (n=43, 20 animals, t42=4.95, p<0.001; Figure 4A, C). When a saturating concentration of ME (10 μM) was used, GABA-A IPSCs were inhibited to 58.5±3.17% (n=3) of control similar to the inhibition mediated by DAMGO (1 μM, 66.0±5.3% of control). In slices from morphine treated animals the sub-saturating concentration of ME (1 μM) decreased the IPSC to 84.2±2.9% of control (n=13, 4 animals, t12=5.37, p<0.001; Figure 4B, C) the same as in slices from untreated animals. Thus there was no significant tolerance at synapses between interneurons and dopamine neurons (t45=0.41, p=0.69). Likewise, there was no change in PPR (Untreated - from 0.60±0.03 to 0.65±0.05, n=43, t42=1.00, p=0.32; Morphine treated from 0.70±0.04 to 0.73±0.05, n=13, t12=1.25, p=0.24). Thus, chronic morphine treatment did not alter the opioid sensitivity of GABA-A IPSCs from interneurons.

Figure 4. Opioid inhibition of IPSCs evoked from interneurons in slices from morphine treated animals.

ChR2 was expressed in the VTA and GABA-A IPSCs were recorded from dopamine neurons in the VTA/SN. LED flashes (0.2–0.4 ms; 50 ms interval; 473 nm) were used to evoke IPSCs. A. Superimposed traces of GABA-A IPSCs from control animals. Morphine (1 μM) and ME (1 μM) application caused a small and significant inhibition of GABA-A IPSCs. B. Superimposed traces of IPSCs from morphine treated animals (MTA). Morphine (1 μM) and ME (1 μM) again caused a very small inhibition of the IPSCs. C. Summary graph comparing the amount of inhibition in control (black) and MTA (gray) by morphine (1 μM) and ME (1 μM). The inhibition induced by morphine and ME was significant, but there was no difference between the inhibition in slices from untreated versus morphine treated animals. Traces shown are averages of 5 sweeps. Error bars indicate SEM. Not significant (NS) unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

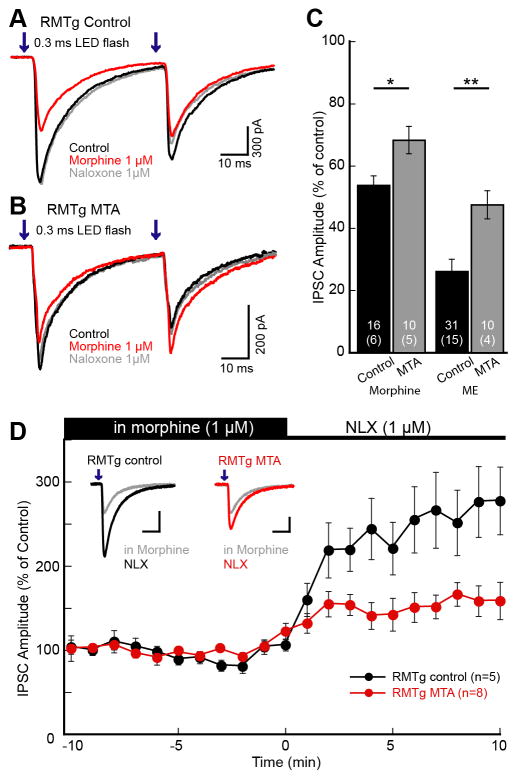

Tolerance to morphine - RMTg

The opioid inhibition of GABA-A IPSCs from the RMTg to dopamine neurons was examined in slices from control and morphine treated animals. Using a small volume of viral injection, the expression of ChR2 was limited to the RMTg (Matsui and Williams, 2011). Recordings were made from dopamine neurons and wide field light stimulation (1–1.5 ms duration paired stimuli; 50 ms interval; every 30 seconds, LED) was used to evoke GABA IPSCs. In slices from untreated animals, morphine (1 μM) inhibited IPSCs to 53.9±3.0% of control (n=16, 6 animals, t15=15.6, p<0.0001, Student’s t test; Figure 5A, C). Morphine also inhibited IPSCs in slices from morphine treated animals to 68.4±4.4% of control (n=10, 5 animals, t9=7.20, p<0.0001) and this inhibition was significantly smaller than in untreated animals (t16=2.74, p=0.01; Figure 5B, C). In slices from control animals, the PPR significantly increased from 0.68±0.04 in baseline to 0.92±0.07 in morphine (n=16, t15=5.01, p=0.0001; Figure 5D). In slices from morphine treatment animals, the PPR also increased from 0.69±0.08 to 0.90±0.06 (n=9, t8=5.57, p=0.0005; Figure 5D). Thus, the inhibition of GABA-A IPSCs was consistent with a presynaptic mechanism.

Figure 5. Chronic morphine treatment reduced the inhibition of GABA IPSCs from RMTg.

ChR2 was expressed in the RMTg and GABA-A IPSCs were recorded from dopamine neurons in the VTA/SN. Pairs of LED flashes (0.3 ms; 50 ms interval; 473 nm) were used to evoke IPSCs. A. Superimposed traces of paired GABA-A IPSCs from control animals. Morphine inhibited GABA-A IPSCs and subsequent application of antagonist naloxone (1 μM) reversed that inhibition. B. Superimposed traces of GABA-A IPSCs from morphine treated animals (MTA). Morphine caused less inhibition of IPSCs in MTA compared to control animals. C. Summary graph comparing the amount of inhibition induced by morphine (1 μM) and ME (1 μM) in slices from control (black) and MTA (gray). D. Time course of the naloxone induced increase in GABA-A IPSCs from RMTg comparing control vs. MTA. Slices were prepared and maintained in morphine (1 μM) and naloxone-reversed IPSCs were plotted every minute. The amplitude was normalized to the average over the first 10 min prior to naloxone application. RMTg inputs from both control and MTA increased significantly. The increase in slices from untreated animals was significantly larger than in slices from MTA. Traces shown are the average of 5 sweeps. Error bars indicate SEM. *p< 0.05 and **p<0.001 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

The sensitivity of the RMTg input to ME (1 μM) was also examined in slices from control and morphine treated animals. ME (1 μM) decreased GABA-A IPSCs in slices from both control and morphine treated animals (untreated 26.2±3.8% of control, n=31, 15 animals, t30=19.2, p<0.0001; morphine treated 47.6±4.5% of control, n=10, 4 animals, t9=11.6, p<0.0001), and the degree of inhibition was significantly greater in slices from untreated animals (t23=3.61, p=0.001; Figure 5C). The PPR was also increased (untreated − 0.79±0.06 to 1.21±0.14, n=6, t5=5.32, p=0.003; morphine treated − 0.75±0.05 to 0.97±0.06, n=10, t9=5.98, p=0.0002; Figure 5E). The results indicate that chronic morphine treatment causes a decrease in the sensitivity to opioids and is taken as a sign of tolerance.

To examine acute withdrawal, brain slices from both untreated and morphine treated animals were prepared and maintained in morphine (1 μM). This concentration was chosen because it mimics the circulating concentration in morphine treated animals (Levitt and Williams, 2012; Quillinan et al., 2011). GABA-A IPSCs from the RMTg were evoked and acute withdrawal was induced with the addition of naloxone (1 μM). In slices from untreated animals, naloxone reversed the morphine-induced inhibition reaching a steady state within 2 min. The average amplitude of the IPSCs was measured before and 4–10 min after application of naloxone. In slices from control animals, the GABA IPSCs from the RMTg increased to 256.1±37.3% of baseline (n=11, 5 animals, t10=4.18, p=0.002), whereas the amplitude was only increased by 148.3±14.6% in slices from morphine treated animals (MTA, n=13, 8 animals, t12=3.30, p=0.006; Figure 5D). The change in GABA-A IPSC amplitude was significantly greater in slices from control animals (t13=2.69, p=0.018; Figure 5D) and is consistent with the development of tolerance, without an indication of a withdrawal-induced increase in GABA release. The PPR was also decreased in slices from both untreated animals (from 1.17±0.11 to 0.82±0.08, n=10, t9=4.69, p=0.001) and morphine treated animals (MTA, from 1.05±0.10 to 0.68±0.05, n=12, t11=5.21, p=0.0003). The time constant of decay of the IPSC was similar in slices from both groups (8.11±0.44 ms and 8.08±0.40ms, respectively) suggesting that there was no obvious change in postsynaptic GABA receptor expression.

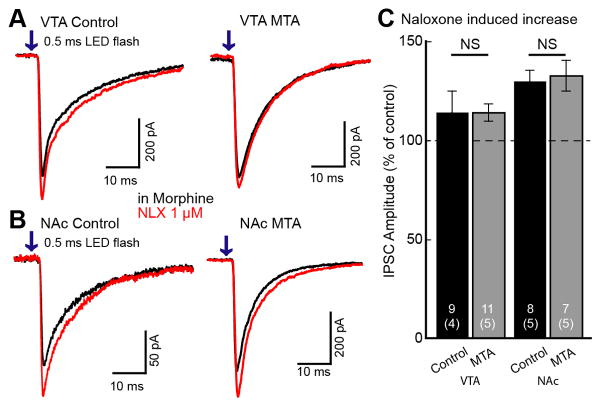

Lack of withdrawal - VTA and NAc

GABA IPSCs from interneurons in the VTA and projections from the NAc were examined in slices from untreated and morphine treated animals that were maintained in morphine (1 μM). Acute withdrawal was induced by addition of naloxone (1 μM). The amplitude of IPSCs evoked from VTA interneuron terminals increased following application of naloxone to a similar degree in slices from untreated and morphine treated animals (untreated 114.3±10.6%, MTA 113.8±4.5% of control; t10=0.0088, p=0.99, Student’s t test unpaired comparison; Figure 6A, C). IPSCs evoked from the NAc were also increased following the application of naloxone (1 μM) in slices from untreated (130.2%±5.50% of baseline, n=8, t7=5.50, p=0.0009) and morphine treated animals (MTA 133.1±7.81% of control, n=7, t6=4.23, p=0.0055; Figure 6B, C). The increase in IPSC amplitude was not significantly different between untreated and morphine treated animals (MTA t11=0.30, p=0.77, Student’s t test unpaired comparison). Taken together the results indicate that these GABA inputs to dopamine neurons did not exhibit a significant rebound increase in GABA release following acute withdrawal from morphine.

Figure 6. Naloxone reversal of morphine inhibition in the VTA and NAc.

Slices were prepared and maintained in morphine (1 μM). Superfusion of naloxone increased GABA-A IPSCs. A. Representative traces of IPSCs from VTA input taken from control (left) and morphine treated animals (MTA; right). Red traces show that naloxone caused a small increase in IPSCs from the VTA input. B. Representative traces of IPSCs from NAc in control (left) and MTA (right). C. Summary graph shows the naloxone-induced increase in IPSCs from the VTA and NAc in control and morphine treated animals (MTA). In VTA and NAc, there was no difference in the naloxone-induced increase in IPSCs between control and MTA. Traces shown are an average of 5 sweeps. Error bars indicate SEM. NS -unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

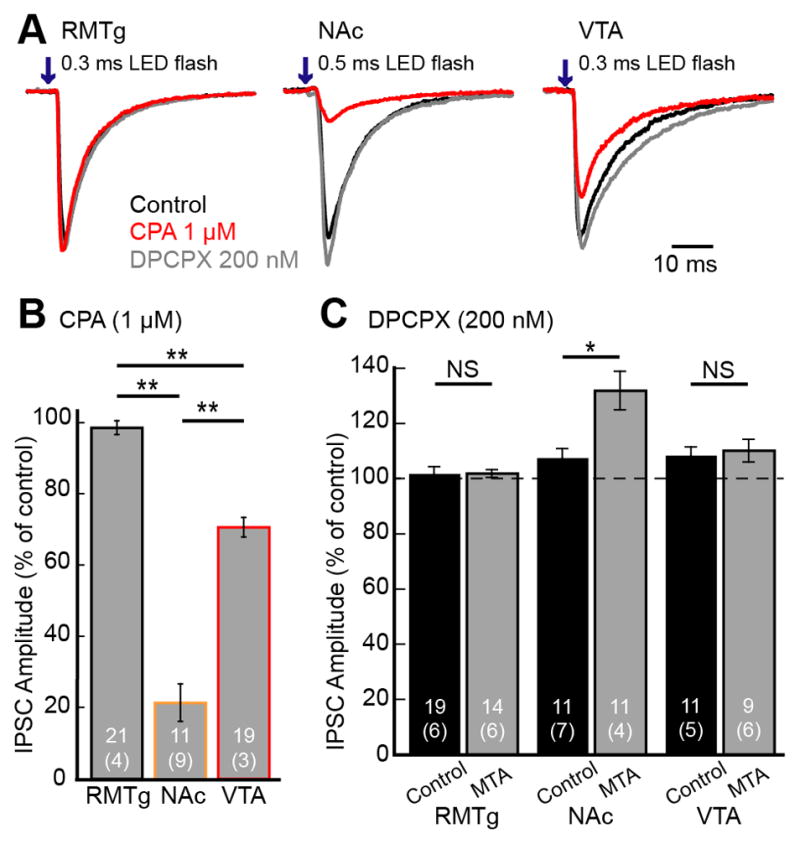

The role of adenosine receptors

Previous studies have found that adenosine tone was elevated during withdrawal from chronic morphine treatment resulting in an inhibition of GABA release through activation of presynaptic adenosine receptors in the VTA/SN (Bonci and Williams, 1996; Shoji et al., 1999). It is not known which GABAergic terminals express A1 adenosine receptors. The IPSCs evoked from the RMTg were insensitive to the adenosine receptor agonist, N6-cyclopentyladenosie (CPA 1 μM; 98.7±1.9%, n=21, 4 animals, t20=0.69, p=0.50; Figure 7A, B). IPSCs evoked from local interneurons were decreased to 70.7±2.8% of control (n=19, 3 animals, t18=10.6, p<0.0001) by CPA (1 μM) without a change in PPR (n=14, t13=1.21, p=0.25). In contrast, the IPSCs evoked from the NAc input were inhibited by CPA to 21.6±5.3% of control (n=11, 9 animals, t10=14.8, p<0.0001; Figure 7A, B) and the PPR was significantly increased from 0.88 to 1.36 (n=8, t7=2.57, p=0.037).

Figure 7. Adenosine receptor regulation of GABA-A IPSCs in dopamine neurons.

A. Representative traces of IPSCs evoked from the RMTg, NAc and VTA in the control (black) and in the presence of the adenosine agonist CPA (1 μM; red), and subsequent application of the adenosine antagonist, DPCPX (200 nM; gray). B. Summary graph of the inhibition of IPSCs induced by CPA (1 μM). C. Summary graph of the increase in the GABA IPSCs induced by the adenosine receptor antagonist, DPCPX (200 nM) in slices from untreated and morphine treated animals (MTA). Traces shown are an average of 5 sweeps. Error bars indicate SEM. *p< 0.05 and **p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA with bonferroni’s post-test or unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

Basal adenosine tone was examined using application of the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist, DPCPX (200 nM). DPCPX failed to increase GABA-A IPSCs evoked from the RMTg in slices from untreated and morphine treated animals (untreated 101.7±2.6% of control n=19, 6 animals; MTA 101.9±1.5%, n=14, 6 animals; t27=0.06, p=0.95, Student’s t test unpaired comparison; Figure 7C). The IPSCs evoked from VTA interneurons were significantly increased in amplitude by DPCPX (200 nM) in slices from control and morphine treated animals (untreated 108.4±3.1%, n=11, 5 animals; and MTA 110.2±4.2%, n=9, 6 animals; respectively). Thus there was some adenosine tone in slices from untreated animals; however, there was no significant difference in increasing GABA-A IPSCs after chronic morphine treatment (t20=0.34, p=0.74).

IPSCs evoked from the NAc in slices from untreated animals were also increased by DPCPX (107.6±3.4%, n=11, 7 animals, t10=2.26, p=0.047, Student’s t test), suggesting inhibition of basal adenosine receptor activation. In slices from morphine treated animals, however, DPCPX increased the IPSCs to 131.9±7.0% of control (n=11, 4 animals, t10=4.57, p=0.001, Student’s t test), significantly larger than in slices from untreated animals (t14=3.14, p=0.0071, Student’s t test unpaired comparison). Thus, adenosine tone was elevated in slices during acute withdrawal and this increase in adenosine receptor activation opposed the naloxone-induced increase in GABA release.

Discussion

Opioids inhibit GABA IPSCs on dopamine neurons and the amplitude of that inhibition is dependent on the afferent pathway. The inhibition of IPSCs produced by opioid agonists was the greatest on afferents from the RMTg, the least on local interneurons and intermediate on the projections from the NAc. The sensitivity to adenosine, on the other hand, was the greatest for inputs from the NAc and the least at terminals arising from the RMTg. The increase in adenosine tone in slices from morphine treated animals suggests that these GABA releasing terminals play very different roles in the acute and chronic actions of opioids.

MOR agonist regulation of VTA GABA neurons

It is established that opioids hyperpolarize GABA neurons in the VTA by activating a GIRK conductance (Chieng et al., 2011; Jalabert et al., 2011; Johnson and North, 1992). Likewise, opioids activate a potassium conductance in neurons of the RMTg (Matsui and Williams, 2011). There is, however, a marked difference in the amount of presynaptic inhibition induced by opioids. GABA input from the RMTg may effectively suppress the activity of dopamine neurons. This is supported by experiments carried out in vivo where infusion of morphine into the RMTg increased the firing rate of dopamine neurons (Jalabert et al., 2011). When morphine was infused into the VTA, there was no change in the firing of dopamine neurons (Jalabert et al., 2011). The increased inhibition observed from the RMTg may result from (1) a higher expression of MORs, (2) a difference in the coupling efficiency or (3) GABA neurons in the VTA may be a heterogeneous population of opioid sensitive and insensitive neurons.

The regulation of dopamine cells through the activity of interneurons in the VTA has also been established. When GABA neurons in the VTA were selectively stimulated using ChR2 in mice, aversive behavior and a reduction of free-reward consumption was observed (Tan et al., 2012; van Zessen et al., 2012). These behavioral consequences were thought to result from the GABA-dependent inhibition of dopamine neurons. The present study in the rat supports these observations since activation of GABA neurons in the VTA reliably evoked IPSCs in dopamine neurons. Thus, although GABA neurons in the VTA contribute to the activity of dopamine cells (Li et al., 2012; Steffensen et al., 1998), it appears that opioids have a minimal role in this pathway.

There are other GABA inputs to the ventral midbrain including the ventral pallidum/globus pallidus, laterodorsal tegmentum, pedunculopontine nuclei and diagonal band of Broca and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Bolam and Smith, 1990; Charara et al., 1996; Hjelmstad et al., 2013; Omelchenko and Sesack, 2005; Smith and Bolam, 1990; Tepper et al., 1995; Tepper and Lee, 2007; Watabe-Uchida et al., 2012). Using a saturating concentration of DAMGO (1 μM), the ChR2-induced GABA release from terminals originating in the ventral pallidum was decreased by about 30% on both dopamine and GABA neurons in the VTA (Hjelmstad et al., 2013). The role of these GABA afferent pathways during opioid withdrawal remains to be determined.

A direct projection from the NAc to dopamine neurons

A direct connection from neurons in the NAc to dopamine neurons was identified in the present study. This observation is unlike previous work which did not observe a direct NAc-dopamine neuron connection (Chuhma et al., 2011; Xia et al., 2011) or that found only a subset of non-GABA neurons that received a direct GABA input (Bocklisch et al., 2013). In the present study, GABA input onto dopamine neurons from NAc was also observed infrequently compared to the frequency of GABA inputs onto GABA neurons in the VTA and SNr. A recent trans-synaptic tracing study found that striatal subregions consisting of patch and matrix send differential projections to dopamine and GABA neurons, respectively (Watabe-Uchida et al., 2012). In MOR knockout mice, prodynorphin positive MSNs in striatal patches and the NAc project to the VTA/SN and the activation of re-expressed MORs in this pathway disinhibits dopamine neurons (Cui et al., 2014). The GABA-A IPSCs from the NAc to dopamine neurons in the present study were inhibited by dopamine acting on D2 receptors. This result was unexpected based on the assumption that solely direct pathway MSNs known to express D1 receptors project from the NAc to dopamine neurons. However, previous evidence suggests that a small percentage of MSNs co-expressed D1 and D2 receptors (Lester et al., 1993; Perreault et al., 2010; Thibault et al., 2013). Whether the opioid sensitive input from NAc to dopamine neurons described in this study originates from the so-called “indirect pathway” or an unidentified subset of neurons is not known.

Tolerance and withdrawal after chronic morphine treatment

Adaptive changes in transmitter release at various terminals following chronic morphine treatment vary widely, ranging from tolerance (Bonci and Williams, 1997; Fyfe et al., 2010; North and Vitek, 1980) to sensitization (Ingram et al., 1998; Pennock et al., 2012) and the addition of new opioid sensitive cAMP-dependent effectors (Bagley et al., 2005; Hack et al., 2003). These inconsistencies could be due to differences in (1) MOR/effector coupling, (2) the efficiency of coupling, (3) location of synapses, (4) species and (5) the protocol used for chronic morphine treatment. For example, there are distinct difference in the opioid-sensitive GABA synapses in the periaqueductal gray (PAG) between rats and mice using the same chronic morphine treatment (Hack et al., 2003; Ingram et al., 1998). A withdrawal-induced increase in GABA release was revealed in the rat PAG. In the mouse PAG, however, the increase in GABA release was only observed after inhibition of presynaptic adenosine receptors.

There are also marked differences in results obtained using different morphine treatment protocols. The results obtained using continuous or repeated injection of morphine vary considerably. Continuous exposure to morphine resulted in the addition of an opioid sensitive cAMP/PKA dependent effector pathway that resulted in an additional inhibition of GABA IPSCs (Ingram et al., 1998). However, repeated injections of morphine (i.e. twice a daily) failed to induced the cAMP/PKA mechanism (Fyfe et al., 2010).

This study supports previous observations made in the guinea pig VTA that chronic morphine treatment results in signs of withdrawal (Bonci and Williams, 1997). Although tolerance developed at RMTg terminals, an adenosine-dependent sign of withdrawal was not observed due to lack of A1 adenosine receptors. Expression of tolerance or withdrawal was not observed at terminals from VTA interneurons. In contrast, there was a significant adenosine-dependent inhibition of GABA release from NAc terminals and an increase in the adenosine tone in slices from morphine treated animals. The present results are similar to experiments that examined the GABA-B IPSP in dopamine neurons in guinea pig slices (Shoji et al., 1999). That study proposed that projections from the striatum and NAc selectively activated GABA-B receptors on dopamine neurons based on pharmacological experiments (Shoji et al., 1999). Similar experiments using optogenetic stimulation have not been reported.

There were marked differences in the sensitivity of GABA-A IPSCs to the adenosine agonist, CPA, with selective activation of specific GABA-A IPSCs using ChR2 expression. With the use of electrical stimulation, most IPSCs were insensitive to the activation of adenosine receptors. There were, however, a few experiments where the IPSC was almost completely blocked by CPA. Thus it appears that electrical stimulation often results in the activation of adenosine insensitive terminals that most likely arise from local interneurons or projections from the RMTg.

Conclusion

The present results indicate that opioid receptor-dependent disinhibition of dopamine neurons can be mediated by multiple GABA inputs. Given the distinct difference in the amount of opioid inhibition between the GABA afferents, it seems likely that the projection from the RMTg plays a dominant role in acute opioid disinhibition of dopamine neurons. This is particularly clear when using the partial agonists, morphine, which inhibited GABA IPSCs from interneurons and NAc afferents to a much lesser extent compared with those from the RMTg. After chronic morphine treatment, tolerance to opioids and a withdrawal-induced increase in GABA IPSCs were expressed in separate terminals. Thus, the balance of inhibitory input to dopamine neurons was modulated by chronic morphine treatment.

Experimental Procedures

All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of Oregon Health & Science University and the Animal Care and Use Committees approved all of the experimental procedures.

Intracerebral microinjections

Male and female Sprague-Dawley rats (p20–22, Charles River Laboratories) were used for intracerebral microinjections. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and immobilized in a Stereotaxic Alignment System (Kopf Instruments). Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) was expressed using adeno-associated virus (AAV) constructs prepared by the Vollum Institute Viral Core (Portland, OR). The vector AAV-CAG-ChR2-Venus (serotype DJ, 100 nl; 5 ×1012 genomes/ml) was injected bilaterally using a nanoject II (Drummond Scientific Company) into VTA [from bregma (in mm); −4.35 anteroposterior, ±0.8 lateral, −7.5 ventral], NAc [from bregma (in mm); 1.0 anteroposterior, ±1.8 lateral, −5.6 ventral], or RMTg [from bregma (in mm); −5.7 anteroposterior, ±0.8 lateral, −7.25 ventral]. Experiments were performed in 55 of 61 rats where injections were successfully placed in the VTA, 36 of 49 rats with injections in the NAc, and 35 of 41 rats with injections in the RMTg. Acute brain slices were prepared 13–40 days after the VTA injection, 21–28 days after NAc injection, and 17–35 days after RMTg injections. ChR2 expression at the injection sites was confirmed before experiments. Animals were excluded from the study when ChR2 expression spread outside of the target.

Chronic morphine treatment

Rats were chronically treated with morphine sulfate (National Institute on Drug Abuse) using continuous-release osmotic pumps (2ML1; Alzet, Cupertino, CA). The osmotic pumps have a mean filled volume of 2 ml and released 10.1±0.2 μl/hr. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane a few weeks after ChR2 injections. A small incision was made to insert an osmotic pump subcutaneously. Each osmotic pump delivered 50 mg•kg−1•d−1 of morphine in water. Experiments were performed 6–8 days after implantation.

Slice preparation and recording

Rats (150–300 g) were anesthetized with isoflurane and killed. Brains were quickly removed and placed in a vibratome (Leica). Sagittal slices (220–230 μm) were prepared in ice-cold physiological solution containing the following (in mM): 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.4 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 11 D-glucose, and 0.005 MK-801. Slices were incubated in warm (35 °C) 95%O2/5%CO2 oxygenated saline containing MK-801 (10 μM) for at least 30 min. Slices containing the midbrain or NAc were then transferred to the recording chamber that was constantly perfused with 35°C 95%O2/5%CO2 oxygenated saline solution at the rate of 1.5–2 ml/min.

Midbrain and NAc neurons were visualized with a 40x water-immersion objective on an upright fluorescent microscope (BX51WI, Olympus USA) equipped with gradient contrast infrared optics. Wide field activation of ChR2 was achieved with collimated light from an LED (470 nm; Thorlabs). A 20–100 μm diameter focal laser spot (473 nm laser, IkeCool) was used to activate a ChR2 within the VTA using a 40x objective. Physiological identification of dopamine neurons was based on the presence of D2-autoreceptor-mediated GIRK currents and the rate of spontaneous action potential activity (1–5 Hz) with spike widths ≥1.2 ms (Chieng et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2006; Li et al., 2012; Ungless et al., 2004). The identification of MSNs and CINs were based on the size/membrane capacitance, the resting membrane potential and opioid sensitivity (Britt and McGehee, 2008).

Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings were made using an Axopatch-1D amplifier (Molecular Devices). All recordings were digitized at 10 kHz and filtered at 5 kHz. GABA-A IPSCs were recorded with patch pipettes (2–2.5 MΩ) filled with an internal solution containing the following (in mM): 57.5 KCl, 57.5 K-methylsulfate, 20 NaCl, 1.5 MgCl2, 5 HEPES (K), 10 BAPTA, 2 ATP, 0.2 GTP, and 10 phosphocreatine, pH 7.35, 280 mOsM. All neurons were voltage clamped at −60 mV. Series resistance was monitored throughout the experiment (range; 3–15 MΩ), and compensated by 80%. GABA-A IPSCs were evoked by the activation of ChR2 (2 stimuli at 20 Hz; every 20 or 30 s). All recordings were performed in the presence of 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3 (1H,4H)-dione (DNQX; 10 μM) to isolate GABA-A IPSCs. Naloxone was applied following DAMGO and U69593 in order to reverse the inhibition in a reasonable period of time.

Data Analysis

Data were collected on a Macintosh computer using AxoGraphX (Axograph Scientific), and stored for offline analysis. Statistical significance was assessed with Student’s t tests or ANOVA (Bonferonni’s post hoc analysis); *p< 0.05 and **p<0.001. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

In situ hybridization

Seventeen days after virus containing the ChR2-Venus construct was injected, rats were anesthetized with an overdose of pentobarbital (400 mg/kg, i.p. injection) and transcardially perfused with 10% sucrose followed by 4% formaldehyde in PBS. Brains were removed and postfixed overnight in 4% formaldehyde at 4°C. The in situ hybridizations were performed as previously described (Jarvie and Hentges, 2012) with the exception that glutamate decarboxylase (Gad) 65 and 67 mRNAs were simultaneously detected to reveal all Gad positive cells with one fluorophore. In brief, sagittal slices (50 μm) containing the VTA were prepared on a vibratome and placed in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) treated PBS. The tissue was exposed to proteinase K (10 μg/mL) diluted in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Tissue was then rinsed in PBST containing glycine (2 mg/mL) to inactivate the proteinase K and then subjected to two 5-minute washes in PBST. Slices were then postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/0.2% gluteraldehyde in PBST for 20 minutes at room temperature and then rinsed in PBST. Sections were dehydrated in ethanol of increasing concentrations (50, 70, 95, and 100%) and then rinsed briefly with PBST before being placed into hybridization buffer containing the following: 66% formamide, 13% dextran, 260 mM NaCl, 13 mM Tris, 1.3 mM EDTA, 0.5 mg/mL yeast tRNA, 10 mM DTT, and 1X Denhardt’s Solution (pH 8.0). After 1 h in hybridization buffer probes were added.

Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled antisense RNA probes for the 65 and 67 kDa isoforms of GAD were made as previously descrived (Jarvie and Hentges, 2012). The Gad67 probe corresponded to base pairs 1196–2001 of accession number NM_017007.1, which has 94% homology with the cDNA for rat Gad67. Gad65 was labeled using two probes simultaneously corresponding to base pairs 312–945 and 940–1770 of accession number NM_012563.1, both of which have 100% homology with rat cDNA. Each probe was used at a concentration of 150 pg/μl. The Gad67 probe was hybridized first for 18–20 h at 70°C, then the tissue was moved into hybridization buffer containing the Gad65 probes and incubated for 20 h at 52°C. Sense probes were used to establish specificity of antisense probes.

Following hybridization, sections were subjected to three 30-minute washes with 50% formamide in 5XSSC (pH 4.5) and three 30-minute washes with 50% formamide in 2xSSC at 60°C. Tissue was then digested for 30 min at 37°C with RNAse A (20 μg/mL) in Tris buffer plus 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.0 then washed 3 times in TNT (0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.15M NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20), and blocked for one hour at room temperature in TNB (TN plus 0.5% Blocking Reagent provided in the TSA kit, Perkin Elmer). Venus fluorescence was quenched by the in situ hybridization procedure, however antigenicity remained allowing immunohistochemical detection of the ChR2-Venus. For detection of Venus and DIG, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with sheep anti-DIG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Roche Applied Sciences, 1:1000) and chicken anti-GFP (abcam ab13970, 1:2000) in TNB. After 3 washes in TNT, sections were subjected to a 30-minute biotin amplification using a TSA Plus Biotin Kit (Perkin Elmer) following manufacturer’s instructions. After biotin amplification, sections were incubated for 30 minutes in streptavidin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, 1:1000), then washed 3 times in TNT. Finally, sections were incubated for 2 hours in donkey anti-chicken conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch), washed 3 times in TNT. Sections were then placed on glass slides and cover-slipped using Aqua Poly/Mount (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA).

Immunofluorescence

The retrograde tracer Cholera Toxin B (CTX) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, 1:1000) was injected into the rat VTA (coordinates x=+/−0.8, y=−4.35, z=−7.5 from Bregma) at 21 days postnatal. Fourteen days following the injection, rats were anesthetized with isoflourane and transcardially perfused with 10% sucrose followed by 4% formaldehyde in PBS. Brains were removed and postfixed overnight in 4% formaldehyde at 4°C. Coronal slices (50 μm) containing the NAc were prepared using a vibratome and rinsed 3x in PBS. Slices were rinsed in blocking/permeabilizing solution (0.5% fish skin gelatin, 0.2% Triton-X) for 2 hours then incubated in Methionine Enkephalin Antibody (Immunostar #20065) at a 1:100 dilution in blocking solution for 2 hours at room temperature followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. Slices were rinsed 3x in PBS (15, 45, and 60 minutes) then incubated for 1 hour in an Alexa Fluor 647 secondary antibody (Invitrogen goat anti-rabbit, 1:1000). Slices were rinsed 4x in PBS (5, 10, 15, and 30 minutes) and mounted on glass slides in preparation for confocal microscopy.

Image and Analysis

Images were collected with a Zeiss laser scanning confocal LSM780 microscope. For In situ hybridization, Z-stack tile images were taken from all of the tissue containing VTA and SNc. The percentage of co-localized neurons was calculated by counting the total number of colabeled neurons divided by the total ChR2 positive neurons. In order to count the neurons co-labeling ChR-2 and GAD, ChR2 positive neurons were identified first and observed the co-localization with GAD65/67. For immunofluorescent images, Z-stack tile images were taken using a 20x lens with a 2x digital zoom. The 488 and 647 fluorophores have non-overlapping spectra however, we manually set a maximum of 600 nm for the 488 fluorophore and a minimum of 640 nm for the 647 fluorophore during imaging to ensure against bleed-through. Ten slices spanning the NAc from each of 3 animals were visualized. To determine co-localization, CTX positive neurons were identified first and then the co-localization with Enkephalin was determined. Co-localization was confirmed by at least 3 unbiased individuals. The images were analyzed using Fiji software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Materials

Drugs were applied by bath perfusion. The solution containing [Met5]enkephalin (ME) included the peptidase inhibitors, bestatin hydrochloride (10 μM) and thiorphan (1 μM). ME, [D-Ala2, N-Me-Phe4, Gly5-ol]enkephalin (DAMGO), (+)-(5α,7α,8β)-N-Methyl-N-[7-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-oxaspiro[4.5]dec-8-yl]-benzeneacetamide (U69593), naloxone, picrotoxin, SR 95531, dopamine, sulpiride, 4-aminopyridine, DNQX, and tetrodotoxin (TTX) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). MK-801 was purchased from Ascent Scientific (Weston-Super-Mare, UK). CGP55845, N-Cyclopentyladenosine (CPA), 8-Cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) and quinpirole were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. C.P. Ford and members of the Williams laboratory for providing critical feedback on this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants, DA04523, DA34388 (JTW) and DA032562 (STH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bagley EE, Gerke MB, Vaughan CW, Hack SP, Christie MJ. GABA transporter currents activated by protein kinase A excite midbrain neurons during opioid withdrawal. Neuron. 2005;45:433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocklisch C, Pascoli V, Wong JCY, House DRC, Yvon C, de Roo M, Tan KR, Lüscher C. Cocaine Disinhibits Dopamine Neurons by Potentiation of GABA Transmission in the Ventral Tegmental Area. Science. 2013;341:1521–1525. doi: 10.1126/science.1237059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolam JP, Smith Y. The GABA and substance P input to dopaminergic neurones in the substantia nigra of the rat. Brain Res. 1990;529:57–78. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90811-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonci A, Williams JT. A common mechanism mediates long-term changes in synaptic transmission after chronic cocaine and morphine. Neuron. 1996;16:631–639. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonci A, Williams JT. Increased probability of GABA release during withdrawal from morphine. J Neurosci. 1997;17:796–803. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00796.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt JP, McGehee DS. Presynaptic opioid and nicotinic receptor modulation of dopamine overflow in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1672–1681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4275-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg-Martin ES, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Dopamine in motivational control: rewarding, aversive, and alerting. Neuron. 2010;68:815–834. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MTC, Tan KR, O’Connor EC, Nikonenko I, Muller D, Lüscher C. Ventral tegmental area GABA projections pause accumbal cholinergic interneurons to enhance associative learning. Nature. 2012;492:452–456. doi: 10.1038/nature11657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charara A, Smith Y, Parent A. Glutamatergic inputs from the pedunculopontine nucleus to midbrain dopaminergic neurons in primates: Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin anterograde labeling combined with postembedding glutamate and GABA immunohistochemistry. J Comp Neurol. 1996;364:254–266. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960108)364:2<254::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieng B, Azriel Y, Mohammadi S, Christie MJ. Distinct cellular properties of identified dopaminergic and GABAergic neurons in the mouse ventral tegmental area. J Physiol (Lond) 2011;589:3775–3787. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.210807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ, Williams JT, North RA. Cellular mechanisms of opioid tolerance: studies in single brain neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 1987;32:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuhma N, Tanaka KF, Hen R, Rayport S. Functional connectome of the striatal medium spiny neuron. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1183–1192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3833-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor M, Borgland SL, Christie MJ. Continued morphine modulation of calcium channel currents in acutely isolated locus coeruleus neurons from morphine-dependent rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1561–1569. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Ostlund SB, James AS, Park CS, Ge W, Roberts KW, Mittal N, Murphy NP, Cepeda C, Kieffer BL, et al. Targeted expression of μ-opioid receptors in a subset of striatal direct-pathway neurons restores opiate reward. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:254–261. doi: 10.1038/nn.3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobi A, Margolis EB, Wang HL, Harvey BK, Morales M. Glutamatergic and nonglutamatergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area establish local synaptic contacts with dopaminergic and nondopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:218–229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3884-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CP, Mark GP, Williams JT. Properties and opioid inhibition of mesolimbic dopamine neurons vary according to target location. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2788–2797. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4331-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe LW, Cleary DR, Macey TA, Morgan MM, Ingram SL. Tolerance to the antinociceptive effect of morphine in the absence of short-term presynaptic desensitization in rat periaqueductal gray neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:674–680. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.172643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gysling K, Wang RY. Morphine-induced activation of A10 dopamine neurons in the rat. Brain Res. 1983;277:119–127. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90913-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack SP, Vaughan CW, Christie MJ. Modulation of GABA release during morphine withdrawal in midbrain neurons in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:575–584. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelmstad GO, Xia Y, Margolis EB, Fields HL. Opioid modulation of ventral pallidal afferents to ventral tegmental area neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6454–6459. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0178-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram SL, Vaughan CW, Bagley EE, Connor M, Christie MJ. Enhanced opioid efficacy in opioid dependence is caused by an altered signal transduction pathway. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10269–10276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10269.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalabert M, Bourdy R, Courtin J, Veinante P, Manzoni OJ, Barrot M, Georges F. Neuronal circuits underlying acute morphine action on dopamine neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16446–16450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105418108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvie BC, Hentges ST. Expression of GABAergic and glutamatergic phenotypic markers in hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:3863–3876. doi: 10.1002/cne.23127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhou TC, Geisler S, Marinelli M, Degarmo BA, Zahm DS. The mesopontine rostromedial tegmental nucleus: A structure targeted by the lateral habenula that projects to the ventral tegmental area of Tsai and substantia nigra compacta. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:566–596. doi: 10.1002/cne.21891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Opioids excite dopamine neurons by hyperpolarization of local interneurons. J Neurosci. 1992;12:483–488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Churchill L, Klitenick MA. GABA and enkephalin projection from the nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum to the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience. 1993;57:1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90048-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufling J, Veinante P, Pawlowski SA, Freund-Mercier MJ, Barrot M. Afferents to the GABAergic tail of the ventral tegmental area in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:597–621. doi: 10.1002/cne.21983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammel S, Hetzel A, Häckel O, Jones I, Liss B, Roeper J. Unique properties of mesoprefrontal neurons within a dual mesocorticolimbic dopamine system. Neuron. 2008;57:760–773. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester J, Fink S, Aronin N, DiFiglia M. Colocalization of D1 and D2 dopamine receptor mRNAs in striatal neurons. Brain Res. 1993;621:106–110. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt ES, Williams JT. Morphine desensitization and cellular tolerance are distinguished in rat locus ceruleus neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:983–992. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.081547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Doyon WM, Dani JA. Quantitative unit classification of ventral tegmental area neurons in vivo. J Neurophysiol. 2012;107:2808–2820. doi: 10.1152/jn.00575.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobb CJ, Wilson CJ, Paladini CA. A dynamic role for GABA receptors on the firing pattern of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:403–413. doi: 10.1152/jn.00204.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe JD, Bailey CP. Functional selectivity and time-dependence of mu-opioid receptor desensitization at nerve terminals in the mouse ventral tegmental area. Brit J Pharmacol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/bph.12605. (e-pub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui A, Williams JT. Opioid-sensitive GABA inputs from rostromedial tegmental nucleus synapse onto midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:17729–17735. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4570-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair-Roberts R, Chatelain-Badie S, Benson E. Stereological estimates of dopaminergic, GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area, substantia nigra and retrorubral field in the rat. Neuroscience. 2008;152:1024–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA, Vitek LV. The effect of chronic morphine treatment of excitatory junction potentials in the mouse vas deferens. Br J Pharmacol. 1980;68:399–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1980.tb14553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omelchenko N, Sesack SR. Laterodorsal tegmental projections to identified cell populations in the rat ventral tegmental area. J Comp Neurol. 2005;483:217–235. doi: 10.1002/cne.20417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennock RL, Hentges ST. Differential expression and sensitivity of presynaptic and postsynaptic opioid receptors regulating hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:281–288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4654-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennock RL, Dicken MS, Hentges ST. Multiple inhibitory G-protein-coupled receptors resist acute desensitization in the presynaptic but not postsynaptic compartments of neurons. J Neurosci. 2012;32:10192–10200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1227-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreault ML, Hasbi A, Alijaniaram M, Fan T, Varghese G, Fletcher PJ, Seeman P, O’Dowd BF, George SR. The Dopamine D1–D2 Receptor Heteromer Localizes in Dynorphin/Enkephalin Neurons: increased high affinity sate following amphetamine and in schizophrenia. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:36625–36634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.159954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quillinan N, Lau EK, Virk M, von Zastrow M, Williams JT. Recovery from mu-opioid receptor desensitization after chronic treatment with morphine and methadone. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4434–4443. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4874-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Behavioral dopamine signals. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji Y, Delfs J, Williams JT. Presynaptic inhibition of GABA(B)-mediated synaptic potentials in the ventral tegmental area during morphine withdrawal. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2347–2355. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02347.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim LJ, Selley DE, Dworkin SI, Childers SR. Effects of chronic morphine administration on mu opioid receptor-stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS autoradiography in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2684–2692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02684.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y, Bolam JP. The output neurones and the dopaminergic neurones of the substantia nigra receive a GABA-containing input from the globus pallidus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;296:47–64. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen SC, Svingos AL, Pickel VM, Henriksen SJ. Electrophysiological characterization of GABAergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8003–8015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-08003.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KR, Yvon C, Turiault M, Mirzabekov JJ, Doehner J, Labouèbe G, Deisseroth K, Tye KM, Lüscher C. GABA Neurons of the VTA Drive Conditioned Place Aversion. Neuron. 2012;73:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper JM, Martin LP, Anderson DR. GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition of rat substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons by pars reticulata projection neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3092–3103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-03092.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper JM, Lee CR. GABAergic control of substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. Prog Brain Res. 2007;160:189–208. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)60011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault D, Loustalot F, Fortin GM, Bourque MJ, Trudeau LE. Evaluation of D1 and D2 dopamine receptor segregation in the developing striatum using BAC transgenic mice. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritsch NX, Ding JB, Sabatini BL. Dopaminergic neurons inhibit striatal output through non-canonical release of GABA. Nature. 2012;490:262–266. doi: 10.1038/nature11466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungless MA, Magill PJ, Bolam JP. Uniform inhibition of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area by aversive stimuli. Science. 2004;303:2040–2042. doi: 10.1126/science.1093360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Pickel VM. GABA-containing neurons in the ventral tegmental area project to the nucleus accumbens in rat brain. Brain Res. 1995;682:215–221. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00334-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zessen R, Phillips JL, Budygin EA, Stuber GD. Activation of VTA GABA neurons disrupts reward consumption. Neuron. 2012;73:1184–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe-Uchida M, Zhu L, Ogawa SK, Vamanrao A, Uchida N. Whole-Brain Mapping of Direct Inputs to Midbrain Dopamine Neurons. Neuron. 2012;74:858–873. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JT, Ingram SL, Henderson G, Chavkin C, von Zastrow M, Schulz S, Koch T, Evans CJ, Christie MJ. Regulation of μ-opioid receptors: desensitization, phosphorylation, internalization, and tolerance. Pharmacological Reviews. 2013;65:223–254. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.005942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Driscoll JR, Wilbrecht L, Margolis EB, Fields HL, Hjelmstad GO. Nucleus accumbens medium spiny neurons target non-dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7811–7816. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1504-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Wang HL, Li X, Ng TH, Morales M. Mesocorticolimbic glutamatergic pathway. J Neurosci. 2011;31:8476–8490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]