Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to assess changes in the oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) among patients wearing fixed orthodontic appliances 24 h after insertion.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty patients aged between 14 and 24 years (29 males and 31 females; mean age, 17.8 years; SD 3.1 years) were recruited from the Postgraduate Clinic, Department of Children's Dentistry and Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya. The oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) was measured before treatment and 24 h after insertion of the orthodontic appliance. The instrument used to measure OHRQoL was a modified self-administered short version of Malaysian Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-16[M]) questionnaire. The higher the score, the poorer is the OHRQoL.

Results:

Overall score of OHRQoL increased significantly 24 h after insertion (mean 43.5±10.9) as compared to before insertion (mean 34.1±9.2) (P<0.001). Significant changes were found for the following items: Difficulties in chewing, bad breath, difficulties in pronunciation, discomfort in eating, ulcer, pain, avoidances of eating certain foods, difficulties in cleaning, embarrassment, avoid smiling, disturbed sleep, concentration affected, difficulty carrying out daily activities, and lack of self-confidence (P<0.05). Significant changes were also found in the mean difference of OHRQoL for gender (P<0.001).

Conclusion:

OHRQoL was found to deteriorate 24 h after insertion of fixed orthodontic appliances in almost all domains, with significant changes in gender. This information can be used as “informed consent”, which might increase patient's compliance as they are aware of what to expect from initial orthodontic treatment.

Keywords: Fixed appliances, oral health impact profile, oral health-related quality of life, orthodontic treatment

INTRODUCTION

Orthodontic treatment is different from most medical interventions in that it does not cure or treat a condition; but rather, it aims to correct variations from an arbitrary norm.[1] Patients as well as their parents expect orthodontic treatment to enhance their lives in many ways beyond just improving occlusion, mastication, and speech. They view this treatment as a means to achieve a better quality of life (QOL).[2]

Studies have shown that orthodontic therapy affects QOL.[3,4,5,6,7,8] The intensity of the negative impact depends on the type of therapy received. For example, Bernabe et al.[3] found that adolescents wearing fixed appliances had a higher frequency of impact than those wearing removable or both types of appliances simultaneously. Another study done by Miller et al.[4] reported that patients wearing fixed appliance had more negative impact than those who were wearing the Invisalign™ aligners. However, this may have bias effect on the reaction and perception of the patients since Invisalign is generally limited to less complicated cases.[8]

The impact of orthodontic therapy on QOL is also dependent on the time factor. Miller et al.[4] evaluated the differences in QOL impact between subjects treated with Invisalign aligners and those with fixed appliances during the first week of orthodontic treatment using daily diary with modified Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index. It was found that there was a significant time effect on the oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). Participants in both groups reported peaks in impact, especially pain, at Day 1. However, the impact decreased nearly to baseline at Day 7. Zhang et al.[5] reported that compared with pretreatment, a patient's OHRQoL is frequently worse during treatment, although it is better in some aspects such as emotional well-being. The greatest change in OHRQoL occurs during the first month of treatment after insertion of fixed orthodontic appliance.

There are limited studies investigating the OHRQoL in patients 24 h following insertion of fixed orthodontic appliance, which is important for “informed consent” to the patient. By informing the patients the sequelae associated with orthodontic treatment, they can weigh the potential benefits as well as the advantages and disadvantages of orthodontic treatment.[6] For the clinician, the potential benefits are in treatment compliance and in medico-legal situations. Thus, this study was aimed to assess the changes of the OHRQoL 24 h following insertion of fixed orthodontic appliance. A secondary aim of this study was to determine the changes of OHRQoL 24 h following insertion of fixed orthodontic appliance by gender and age group. The information may be useful to improve patient's compliance, as they will be aware of what is to be expected from an initial orthodontic treatment,[9] and hence might improve treatment outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 60 patients seeking orthodontic care at the Postgraduate Clinic, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya, were selected using purposive sampling based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were: Age between 14 and 24 years, skeletal pattern Class I, Class II, or Class III, moderate crowding or spacing in upper and lower arches (4-8 mm), and no therapeutic intervention planned with any extraoral or intraoral appliances other than fixed appliances (e.g., quad-helix, transpalatal arch, or nance button) within the first 6 months of orthodontic treatment. The exclusion criteria were: Patients with severe skeletal pattern (Class II or Class III) who required orthognathic surgery and syndromic patients (cleft lips or palate or both). These patients were reported to have had high levels of oral impact to their lives compared to “normal” population.[10,11]

A Malaysian short version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14[M])[12,13] questionnaire with two extra questions, which is named as OHIP-16[M], was used to measure OHRQoL. OHIP was chosen as the instrument to measure OHRQoL for this study because it is widely used in most of the studies for QOL and has been adapted and validated for Malaysian population.[12,13] Pre-testing of the questionnaires was done to check for the face validity. Three new questions were included based on the outcome of the pre-test of the questionnaires as suggested by patients, which are deemed relevant to orthodontics. The three questions were: “Difficulties in pronunciation” which was included in the functional limitation domain; “pain” which was included in the physical pain domain; and “difficulties in cleaning” which was included in the handicap domain. The question “Have you had to spend a lot of money?” was removed from the handicap domain because the question was not relevant for this study, as most of the patients were schoolchildren who were funded by their parents for daily and treatment expenditure. The questionnaires were prepared in two languages, i.e., Malay and English.

The OHIP-16[M] measures focus on the impact of one's oral health condition on QOL, contributing to seven domains: Functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap. Responses of each item are made on a Likert scale and coded as: 1=never, 2=hardly ever, 3=occasionally, 4=fairly often, and 5=very often. The OHIP-16[M] scores range from 16 to 80, where 16 indicates no impact and 80 indicates the worst impact of one's oral health on QOL. Individual domain scores can be calculated by summing responses to the items within a domain, with higher scores indicating greater impact.

Once patients have agreed to participate in the study, researcher explained about the study to the patients and the nature of their participation. Each patient was given an oral and a written information sheet about the study and written informed consent was obtained before the first questionnaire was administered. For patients below 18 years old, consent was obtained from the patients and parents. All patients signed informed consent forms that described the purpose, benefits, and drawbacks of the study. Patients completed the first questionnaire, which was used as the baseline, before insertion of the fixed orthodontic appliance, and they completed the second questionnaire 24 h after insertion. For the assessment 24 h after insertion, the questionnaire with researcher's self-addressed envelope was administered to patients, which the patients mailed back to researcher after completion.

The fixation of the orthodontic appliances followed the standard protocol given by the manufacturer. Only one operator did the fixation to reduce systematic bias. Brackets were bonded from the second permanent premolar to second permanent premolar and molar tubes were bonded on all first permanent molars. These procedures were done on the same day. A 0.014″ superelastic copper–nickel–titanium arch wire was placed in both arches for initial alignment. The fixation of the brackets and molar tubes was performed 2 weeks after extraction in patients who required extraction in their treatment plan. The first questionnaires were also administered 2 weeks after extraction. This is to allow complete healing of the extraction wound as any pain from the extraction procedure might contribute to bias. Molar tubes were placed instead of the molar bands to eliminate any pain that might arise from the placing of the separator's procedure.

All patients who agreed to participate were given oral healthcare products (consisting of orthodontic toothbrush, fluoride mouthwash, and interdental toothbrush) and reimbursement of transportation cost. Patients who refused to participate were treated as regular patients. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya [DF OT0803/0024(P)].

Data analysis

Data collected were coded and entered into a computer using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software for Windows version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data cleaning was performed to detect any errors during data entry. All corrections were made prior to data analysis.

Mean or median was calculated for the continuous data and percentage for categorical data. To compare the score of OHIP baseline and 24 h post-fixation of orthodontic appliances, paired t-test was used. Independent t-test was used to compare mean differences for gender and age groups – adolescent (14-19 years old) and young adult (20-24 years old). The P value was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

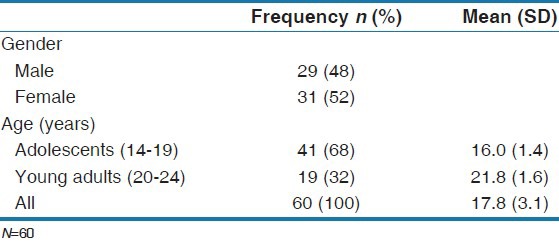

Sixty patients enrolled in the study. All the patients attempted all the questionnaires, which gave 100% response rate. Forty-eight percent of the participants were males and 52% were females [Table 1]. Mean age for the samples was 17.8 years (SD=3.1 years), with 68% in adolescent group (mean 16.0 years, SD=1.4) and 32% in young adult group (mean 21.8 years, SD=1.6) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographics of the study sample

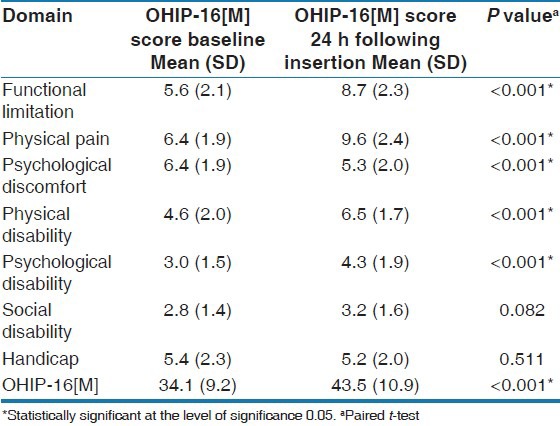

Overall scores of OHIP-16[M] increased significantly 24 h following insertion of fixed orthodontic appliances (P<0.001) [Table 2]. At baseline, the mean score of OHIP-16[M] was 34.1 (SD=9.2) and increased to 43.5 (SD=10.9) after 24 h following insertion.

Table 2.

Mean score OHIP-16[M] baseline and 24 h following insertion for each domain

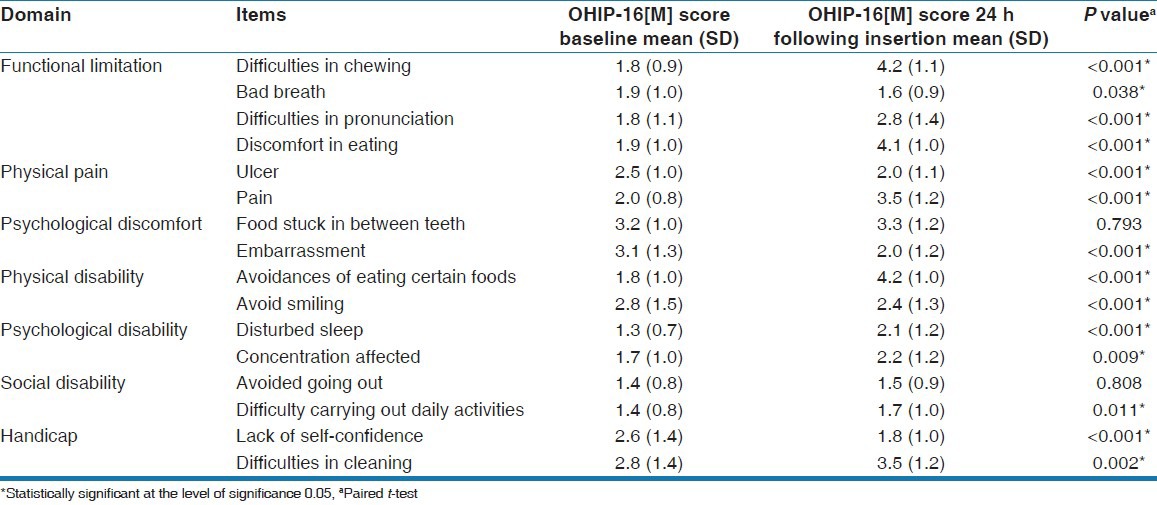

Almost all domains in the OHRQoL, i.e., functional limitation, physical pain, physical disability, psychological disability, and psychological discomfort, were significantly affected 24 h following insertion of fixed orthodontic appliances, except handicap domain and social disability [Table 2]. Almost all items in the OHIP-16[M] were significantly affected 24 h following insertion except food stuck in between teeth or appliances (P=0.793) and avoided going out (P=0.808) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Mean score OHIP-16[M] baseline and 24 h post-fixation for each item

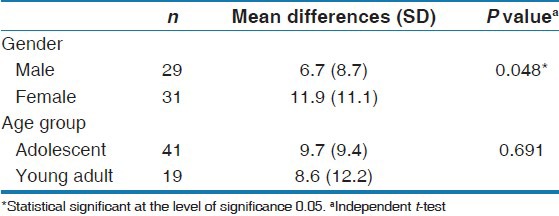

Females tended to report more negative impact on OHRQoL than males. The mean differences were higher among female participants (mean 11.9, SD=11.1) compared to males (mean 6.7, SD=8.7), with significant difference found between them (P<0.05) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparing mean differences of OHIP-16[M] baseline and 24 h following insertion between gender and age groups

Between the two age groups, the impact of OHRQoL 24 h following insertion showed no significant difference (P<0.05), although the adolescent age group had slightly higher mean differences (mean 9.7, SD=9.4) compared to young adults (mean 8.6, SD=12.2) [Table 4].

DISCUSSION

This study was carried out to assess any change in OHRQoL among patients wearing fixed orthodontic appliances 24 h following insertion. As expected, OHRQoL was poorer 24 h following insertion of fixed orthodontic appliances. This supports findings that orthodontic treatments will have impact on patients’ lives, especially during the initial treatment.[4,5]

All domains in this study were affected except the social disability and handicap domains. The domains affected in this study were similar with those reported in other previous studies that focused on the impact of orthodontic treatment after 1 week of fixation. Chen et al.[14] reported in their study that the greatest compromised OHRQoL domains were physical pain, psychological discomfort, and physical disability within 1 week after fixation of the appliances. The impact on functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, and psychological disability was more pronounced in this study as the assessment was done 24 h following insertion. Impact on the social disability and handicap domain was minimal, which may be because these domains depended more on personality characteristics and general daily situations despite the oral condition.

The most affected items in this study were pain, discomfort, eating, speaking, smiling, cleaning, and ulcer. The outcomes were similar with those reported by Chen et al.,[14] who observed that eating, speaking, and smiling were affected within 1 week of orthodontic fixation, but the impact in this study was greater within 24 h following insertion. Many researchers studying pain and discomfort after fixation found that the pain and discomfort started 2 h following insertion, peaked at 24 h, and decreased during the next 3 days following initial arch wire placement.[15,16,17,18,19] This is in accordance with our study wherein we found patients experiencing pain 24 h following insertion. Brown and Moerenhout[20] reported that pain from orthodontic treatments has a definite influence on the daily activities of patients. Several researchers reported that patients had to change their diet to adapt to the pain from orthodontic treatment. Scheurer et al.[17] reported that for patients wearing fixed appliances, eating is the greatest challenge contributing to their QOL.

Patients encountered difficulty 24 h following insertion in performing normal oral functions such as eating, speaking, smiling, and cleaning with the appliances in situ. Mechanical adaptation of this condition triggered injury of the oral mucosa, which may cause ulceration. Patients in this study reported embarrassment and lack of self-confidence 24 h following insertion, which may be because fixation of the appliances attracted people as face is the center of attraction when communicating with people. The study also found that there were sleeping disturbances 24 h post-fixation with fixed orthodontic appliances. This is consistent with studies by other researchers,[17,21,22,23] which reported that sleep quality might be affected by orthodontic appliances during the initial stages of wearing them.

Females experienced more negative impact compared to males as other previous studies claimed.[17,24] This might be due to gender variations in expressing impact of OHRQoL on daily lives. McGrath and Bedi[25] reported that females perceived oral health as having greater impact than males, whether negative impact or positive impact. Kurtz[26] claimed that it is easier for women to describe their characteristics, either positive or negative, whereas men tend to provide the same general descriptions about themselves; furthermore, men are thought to have been socialized to suppress outward signs of pain.[27]

The young adult group reported fewer changes in OHRQoL 24 h following insertion of fixed orthodontic appliances, compared to adolescent group. However, due to small sample size, the data were found to be not significant. Some studies reported adolescent patients feel less pain than older patients.[15,17,20] Adolescents (age 14-19 years) were reported to be more vulnerable to the undesirable psychological effects of treatment and had higher levels of pain than older patients.[20] Muir[28] reported that problems caused by fixed orthodontic appliances were more marked in adult patients than in younger patients. However, Scott et al.[19] reported age does not affect the level of discomfort in patients undergoing treatment. They also reported that gender has no effect on perceived discomfort experienced by subjects undergoing fixed appliance orthodontic treatment.

In this report, patients were not grouped by the bracket type used. This was because the main interest of this study was to assess the changes of OHRQoL in patients 24 h following insertion of fixed orthodontic appliances, regardless of the bracket types used. This might be the limitation of this study as perhaps different bracket types might have different impact of the patient's OHRQoL. Some bracket types might either increase or decrease the impact of patient's OHRQoL 24 h following insertion. Further studies are needed to assess the impact of OHRQoL following orthodontic treatment with regards to different bracket types used. Relatively small sample size was another limitation of this study; hence, the interpretation of the result was made within this limitation.

CONCLUSIONS

OHRQoL deteriorates 24 h following insertion of fixed orthodontic appliances, affecting almost all domains. The changes differ by gender. This information can be used for “informed consent,” which may increase patients’ compliance as they are aware of what is to be expected during the initial phases of orthodontic treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by grants from the University of Malaya, grant number FS173/2008C and P0084/2008C.

Footnotes

Source of Support: University of Malaya, grant number FS173/2008C and P0084/2008C,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.O’Brien K, Kay L, Fox D, Mandall N. Assessing oral health outcomes for orthodontics – measuring health status and quality of life. Community Dent Health. 1998;15:22–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiyak HA. Does orthodontic treatment affect patient’ quality of life? J Dent Educ. 2008;72:886–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernabě E, Sheiham A, de Oliveira CM. Impacts on daily performances related to wearing orthodontic appliances. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:482–6. doi: 10.2319/050207-212.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller KB, McGorray SP, Womack R, Quintero JC, Perelmuter M, Gibson J, et al. A comparison of treatment impacts between invisalign aligner and fixed appliance therapy during the first week of treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:302.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang M, McGrath C, Hagg U. Changes in oral health-related quality of life during fixed orthodontic appliance therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:25–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Z, McGrath C, Hägg U. Changes in oral health-related quality of life during fixed orthodontic appliance therapy: An 18-month prospective longitudinal study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:214–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa AA, Ferreira MC, Serra-Negra JM, Pordeus IA, Paiva SM. Impact of wearing fixed orthodontic appliances on oral health-related quality of life among Brazilian children. J Orthod. 2011;38:275–81. doi: 10.1179/14653121141632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shalish M, Cooper-Kazaz R, Ivgi I, Canetti L, Tsur B, Bachar E, et al. Adult patients’ adjustability to orthodontic appliances. Part I: A comparison between Labial, Lingual, and Invisalign™. Eur J Orthod. 2012;34:724–30. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjr086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sergl HG, Klages U, Zentner A. Pain and discomfort during orthodontic treatment: Causative factors and effects on compliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;114:684–91. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S, McGrath C, Samman N. Quality of life in patients with dentofacial deformity: A comparison of measurement approaches. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:488–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rusanen J, Lahti S, Tolvanen M, Pirttiniemi P. Quality of life in patients with severe malocclusion before treatment. Eur J Orthod. 2012;32:43–8. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saub R. PhD Thesis. Canada: University of Toronto; 2004. Development of an oral health-related quality of life measure for the Malaysian adults’ population: Cross- cultural adaptation of the oral health impact profile. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saub R, Locker D, Allison P. Derivation and validation of the short version of the Malaysian oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:378–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen MU, Wang DW, Wu LP. Fixed orthodontic appliances therapy and its impact on oral health-related quality of life in Chinese patients. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:49–53. doi: 10.2319/010509-9.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones ML. An investigation into the initial discomfort caused by placement of an archwire. Eur J Orthod. 1984;6:48–54. doi: 10.1093/ejo/6.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ngan P, Kess B, Wilson S. Perception of discomfort by patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;96:47–53. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheurer PA, Firestone AR, Bürgin WB. Perception of pain as a result of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod. 1996;18:349–57. doi: 10.1093/ejo/18.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erdinç AM, Dinçer B. Perception of pain during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod. 2004;26:79–85. doi: 10.1093/ejo/26.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott P, Sherriff M, Dibiase AT, Cobourne MT. Perception of discomfort during initial orthodontic tooth alignment using a self-ligating or conventional bracket system: A randomized clinical trial. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30:227–32. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown DF, Moerenhout RG. The pain experience and psychological adjustments to orthodontic treatment of preadolescents, adolescents and adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;100:349–56. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kvam E, Bondevik O, Gjerdet NR. Traumatic ulcers and pain during orthodontic treatment. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17:154–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones ML, Chan C. The pain and discomfort experienced during orthodontic treatment. A randomised clinical trial of two initial aligning arch wires. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992;102:373–81. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(92)70054-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rawji A, Parker L, Deb P, Woodside D, Tompson B, Shapiro CM. Impact of orthodontic appliances on sleep quality. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:606–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kvam E, Gjerdet N, Bondevik O. Traumatic ulcers and pain during orthodontic treatment. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15:104–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGrath C, Bedi R. Gender variations in the social impact of oral health. J Ir Dent Assoc. 2000;46:87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurtz R. Sex differences and variations in body attitudes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1969;33:625–9. doi: 10.1037/h0028274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riley JL, 3rd, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Myers CD, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in the perception of noxious experimental stimuli: A meta-analysis. Pain. 1998;74:181–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muir JC, Wareing MG, McDonald AJ. Orthodontic treatment for adults. N Z Dent J. 1986;82:143–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]