Abstract

Objective:

To assess the relationship between mandibular arch length and widths in a sample of Yemeni subjects aged (18-25) years.

Materials and Methods:

The investigation involved clinical examination of (765) adults; only 214 (101 females, 113 males) out of the total sample were selected to fulfill the criteria for the study sample (normal dento-skeletal relationship). Study models were constructed and evaluated to measure mandibular arch dimensions. The Spearman's correlation coefficient (r) was calculated between the measurements of arch widths and lengths.

Results:

Overall, the male group demonstrated greater transverse and sagittal mandibular dimensions; However, this was only statistically significant for measurements of inter-first and second molar distances and anterior arch length (P < 0.05). Relatively stronger linear relationships were observed between the inter-canine distance and mandibular arch lengths (P < 0.05, Spearman's r ranged between 0.17 to 0.50).

Conclusion:

Among studied mandibular dimensions in subjects with normal dento-skeletal relationship, only the inter-canine distance demonstrated a week to moderate linear relationship with the mandibular arch lengths.

Keywords: Arch length, arch width, dental cast analysis, mandible, Yemeni norms

INTRODUCTION

The size and form of the dental arches vary among individuals according to tooth size, tooth position, pattern of craniofacial growth and by several genetic and environmental factors.[1,2] Survey of arch size could help clinicians in the selection of stock trays, the size of artificial teeth, and the overall forms of artificial dental arch at the wax trial stage are amenable to modification by the dental surgeon and in orthodontic treatment.[3,4]

As orthodontics has advanced as a specialty and the number of adults seeking orthodontic care has increased, an understanding of the changes that normally take place in adult craniofacial structures becomes critical.[5]

The practice and teaching of orthodontics in Yemen is still relatively young. A systematic and well-organized dental care program for any target population in a community requires some basic information, such as the prevalence of the condition. In the more developed parts of the world, where the specialty of orthodontics has been established, adequate baseline information is available.[6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]

Despite efforts in the Arab world during the last decades to make health systems more equitable[14,15,16,17,18] access to dental healthcare is still far from adequate, especially in poor communities. In Yemeni population, there is no previous study carried out on the mandibular arch dimensions. Hence, this study has been designed to provide a baseline data on the mandibular dimensions of Yemeni adults with normal normal dento-skeletal relationship, aged (18-25) years.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval was obtained from both the Ethics Committee of Sana’a University and the Faculty of Dentistry at the University of Sana’a. A brief outline of the study was explained to all participants and consent was obtained prior to participation.

The sample of this study consists of 214 adults aged between 18 and 25 years, among whom 113 were males and 101 females, selected from clinical examination of 765 Yemeni adults, comprised of 387 males and 378 females.

All subjects considered for the sample have the following dental and skeletal features

Full complement of normal shaped permanent teeth (excluding third molars) with no heavy fillings, congenital missing teeth, retained deciduous, and supernumerary teeth.

Class I molar and canine relationships[19,20] and Class I skeletal relationship, decided visually by using the two-finger technique.[20,21]

Normal vertical and horizontal dental relationships (normal overjet and overbite).

No previous orthodontic, orthopedic, facial surgical treatments and no history of bad oral habits such as thumb sucking or mouth breathing.

Well-aligned arches with less than 3 mm of spacing or crowding in either arch.[22]

All the individuals examined under natural light with interchangeable plane mouth mirrors. During this examination, each individual was seated on an ordinary chair with his head being positioned so that the Frankfort horizontal plane is parallel to the floor.

The selected individuals were subjected to a thorough clinical examination to reassure the fulfillment of the required sample specifications.

Certain selected tooth-related points visible in an occlusal view were marked bilaterally with a sharp pencil in the mandibular study casts. Great care was taken to ensure that the landmarks were accurately located on the study casts. Measurements were taken from 214 mandibular dental casts, which were made of dental stone, with the base, made of plaster of Paris. Dental arch dimension measurements were carried out using the modified sliding caliper gauge, which is accurate up to 0.02 mm.

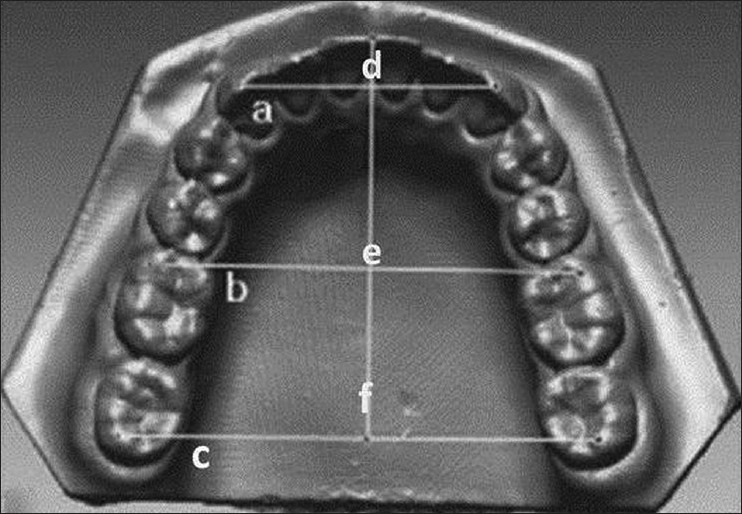

Mandibular Arch Widths [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Dental model measurements, inter-canine width (a), Inter-first molar width (b), Inter-second molar width (c), Anterior arch length (d), Molar arch length (e), Total arch length (f)

a-Inter-canine distance: The linear distance from cusp tip of one canine to the cusp tip of the other.

b-Inter-first molar distance: The distance from the mesiobuccal cusp tip of one first permanent molar, to the mesiobuccal cusp tip of the other.

c-Inter-second molar distance: The distance between the disto-buccal cusp tips of one second permanent molar, to the disto-buccal cusp tip of the other.

Mandibular Arch Lengths [Figure 1]

d-Anterior arch length: The vertical distance from the incisal point to the inter-canine distance at the cusp tip.

e-Molar arch length: The vertical distance from the incisal point perpendicular to a line joining the mesiolingual cusp tip of first permanent molars.

f-Total arch length: The vertical distance from the incisal point to the midpoint of a line joining the disto-buccal cusp tip of the second permanent molars.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill, USA). Descriptive statistics were performed for the calculation of the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, range and coefficient of variation (CV). The t-test was applied to test the level of significance between the mean for males and females for all mandibular arch dimensions. The Spearman's correlation coefficient (r) was also calculated between the measurement of arch widths and lengths in female and males. Statistical significance was predetermined at the 95% level at (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

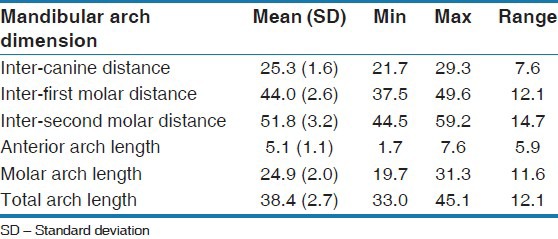

The means and standard deviations (mean ± SD) of the mandibular dimensions are shown in Table 1. The minimum and maximum values were recorded and expressed by the range. It can be noticed that the inter-second molar distances have the widest range while the lowest difference existing in the anterior arch length.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation (SD) of mandibular arch widths (mm) and lengths for the sample

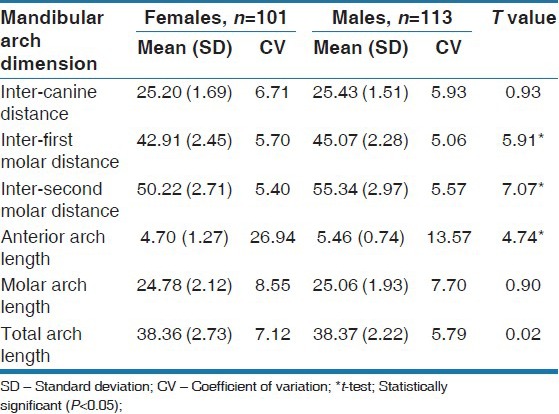

Table 2 depicts the mandibular arch dimensions according to gender. Overall, the male group displayed greater transverse and sagittal mandibular dimensions; However, this was only statistically significant for measurements of inter-first and second molar distances and anterior arch length (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Mandibular arch dimensions (mm) according to gender

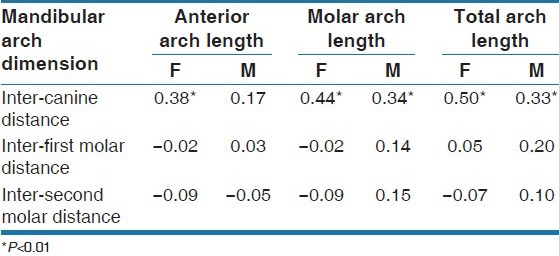

The correlation coefficient was calculated between arch widths and lengths; some of them were highly significant, positive and direct relationship was noted, others showed moderate, weak or negative relationships [Table 3].

Table 3.

Relationship between the mandibular widths and lengths shown with the corresponding spearman correlation coeficients (r)

Statistically significant correlations between the inter-canine distance and mandibular arch lengths were noted, but the r values were not greater than 0.5.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the measurements taken for the dimensions of the mandibular arch, confirmed the accepted view that male dental arches are greater than that of females. In most studies, the arch dimensions depended on the gender of the subjects, with smaller values in females. This may be attributed to the smaller bony ridge and alveolar process of females, the average weakness of musculature in females that play an important role in facial breadth measurements, width and height of the dental arch and the later growth period in males than females.[23]

The findings of this study showed statistically significant difference between males and females for some measurements, this confirms those results previously published by many investigators.[14,22,23] While it contradicted with other investigators.[16,17] Kuntz[24] reported that both sexes had nearly similar inter-canine distance and Ismail et al.[16] reported that females had larger widths than males, but the difference was not statistically significant.

The largest difference between males and females existed in the inter-second molar distance, which might be attributed to the differences in arch form in the sample.

In this study, it seems to indicate also that male group had greater mandibular dimensions in the sagittal direction than female group, this difference was statistically significant in the anterior arch length, which agree with the finding of Raberin et al.[9] and Borgan.[18]

On the other hand, this difference was statistically insignificant in the molar arch length and total arch length, which does not agree with the finding of Raberin et al.[9] and Borgan.[18]

Determinants of the craniofacial dimensions are not very well understood.[25] The difference with the other studies may be attributed to different ethnic groups, sample sizes and environmental factors.

Relationship between the Yemeni Mandibular Arch Dimensions

Different relathinships were observed between the mandibular dental arch dimensions. The craniofacial and dental dimentions represent a highly complex interaction between numerous genetic and environmental factors.[25,26] Overall, the correlation coefficient values were less than 0.5 indicating that the relationship is at best indicating a moderate linear relationship.[27] Studying the descriptive analysis for the mandibular arch width revealed that the strongest relathinships were observed between the inter-canine distance and total arch length, molar arch length and anterior arch length.

It could be also seen that the CV values for all measurements were nearly close to each other, with the anterior arch length distances showing the higher CV than the others.

The inter-canine distance contributes to the different arch forms. The anterior arch length values share the inter-canine distance in the contribution of determining all types of the dental arch forms. Thus, it is not unexpected for the anterior arch length to have the highest coefficient of variation among other dimensions. These results are in agreement with the findings of Andria and Dias.[28]

CONCLUSION

Based on this study it could be said that among studied mandibular dimensions in subjects with normal dento-skeletal relationship, the inter-canine distance showed the strongest linear relationship with the mandibular arch sizes.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harris EF, Smith RJ. Occlusion and arch size in families. A principal components analysis. Angle Orthod. 1982;52:135–43. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1982)052<0135:OAASIF>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrario VF, Sforza C, Miani A, Jr, Tartaglia G. Mathematical definition of the shape of dental arches in human permanent healthy dentitions. Eur J Orthod. 1994;16:287–94. doi: 10.1093/ejo/16.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knott VB. Size and form of the dental arches in children with good occlusion studied longitudinally from age 9 years to late adolescence. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1961;19:263–84. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330190308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mack PJ. Maxillary arch and central incisor dimensions in a Nigerian and British population sample. J Dent. 1981;9:67–70. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(81)90037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishara SE, Jakobsen JR, Treder JE, Stasi MJ. Changes in the maxillary and mandibular tooth size-arch length relationship from early adolescence to early adulthood. A longitudinal study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;95:46–59. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrow GV, White JR. Developmental changes of the maxillary and mandibular dental arches. Angle Orthod. 1952;22:41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills LF. Arch width, arch length, and tooth size in young adult males. Angle Orthod. 1964;34:124–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavelle CL, Foster TD, Flinn RM. Dental arches in various ethnic groups. Angle Orthod. 1971;41:293–9. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1971)041<0293:DAIVEG>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raberin M, Laumon B, Martin JL, Brunner F. Dimensions and form of dental arches in subjects with normal occlusions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1993;104:67–72. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(93)70029-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buschang PH, Stroud J, Alexander RG. Differences in dental arch morphology among adult females with untreated Class I and Class II malocclusion. Eur J Orthod. 1994;16:47–52. doi: 10.1093/ejo/16.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bishara SE, Jakobsen JR, Treder J, Nowak A. Arch width changes from 6 weeks to 45 years of age. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;111:401–9. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(97)80022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bishara SE, Jakobsen JR, Treder J, Nowak A. Arch length changes from 6 weeks to 45 years. Angle Orthod. 1998;68:69–74. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1998)068<0069:ALCFWT>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warren JJ, Bishara SE. Comparison of dental arch measurements in the primary dentition between contemporary and historic samples. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;119:211–5. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.112260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eid A, El-Namrawy M, Kadry W. The relationship between the width, depth and circumference of the dental arch for a group of Egyptian school children. Egypt Orthod J. 1987;1:113–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diwan R, Elahi JM. A comparative study between three ethnic groups to derive some standards for maxillary arch dimensions. J Oral Rehabil. 1990;17:43–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1990.tb01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ismail AM, Hissain N, Hatem S. Maxillary arch dimensions in Iraqi population sample. Iraqi Dental J. 1996;8:111–20. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Khateeb SN, Abu Alhaija ES. Tooth size discrepancies and arch parameters among different malocclusions in a Jordanian sample. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:459–65. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0459:TSDAAP]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borgan BE. Master Thesis. Cairo University; 2001. Dental arch dimensions analysis among Jordanian school children. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angle GM. Classification of malocclusion. Dent Cosm. 1889;41:248–464. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houston WJ, Stephens CD, Tulley WJ. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Wright; 1996. A Textbook of Orthodontics; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills JR. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1987. Principles and Practice of Orthodontics; pp. 16–8. 23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staley RN, Stuntz WR, Peterson LC. A comparison of arch widths in adults with normal occlusion and adults with class II, Division 1 malocclusion. Am J Orthod. 1985;88:163–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(85)90241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramadan OZ. Master Thesis. Mosul University; 2000. Relation between photographic facial measurements and lower dental arch measurement in adult Jordanian males with class I normal occlusion. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuntz TR. Master Thesis. University of Iowa; 1993. An anthropometric comparison of cephalometric and dental arch measurements in classes I normal, class I crowded and class III individuals. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amini F, Borzabadi-Farahani A. Heritability of dental and skeletal cephalometric variables in monozygous and dizygous Iranian twins. Orthod Waves. 2009;68:72–79. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudge SJ. A computer program for the analysis of study models. Eur J Orthod. 1982;4:269–73. doi: 10.1093/ejo/4.4.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borzabadi-Farahani A, Borzabadi-Farahani A, Eslamipour F. The relationship between ICON index and Dental and Aesthetic components of IOTN index. World J Orthod. 2010;11:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andria LM, Dias JC. Relation of maxillary and mandibular intercuspid width to bizygomatic and bigonial breaths. Angle Orthod. 1978;48:154–62. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1978)048<0154:ROMAMI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]