Highlights

-

•

Three different membrane ectopeptidases act as receptors for coronaviruses.

-

•

Coronavirus ectopeptidase receptors are expressed on cells in the respiratory and enteric tract.

-

•

The catalytic activity of ACE2, APN, and DPP4 peptidases is not required for virus entry.

-

•

Evolutionary conservation of these receptors may permit coronavirus interspecies transmissions.

-

•

Binding of coronaviruses to their peptidase receptors may alter their physiological functions.

Abstract

Six coronaviruses, including the recently identified Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, are known to target the human respiratory tract causing mild to severe disease. Their interaction with receptors expressed on cells located in the respiratory tract is an essential first step in the infection. Thus far three membrane ectopeptidases, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4), angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and aminopeptidase N (APN), have been identified as entry receptors for four human-infecting coronaviruses. Although the catalytic activity of the ACE2, APN, and DPP4 peptidases is not required for virus entry, co-expression of other host proteases allows efficient viral entry. In addition, evolutionary conservation of these receptors may permit interspecies transmissions. Because of the physiological function of these peptidase systems, pathogenic host responses may be potentially amplified and cause acute respiratory distress.

Current Opinion in Virology 2014, 6:55–60

This review comes from a themed issue on Viral pathogenesis

Edited by Mark Heise

For a complete overview see the Issue and the Editorial

Available online 22nd April 2014

1879-6257/$ – see front matter, © 2014 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) infect birds and a wide range of mammals, including humans. These positive stranded RNA viruses — belonging to the order Nidovirales, family Coronaviridae, subfamily Coronavirinae [1] — occur worldwide and can cause disease of medical and veterinary significance. Generally, CoV infections are localized to the respiratory, enteric and/or nervous systems, although systemic disease has been observed in a number of host species, including humans [1]. At present, six CoVs have been identified capable of infecting human and all are thought to have originated from animal sources [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-229E were identified in the 1960s and have been associated with the common cold [9, 10, 11]. In 2003, SARS-CoV was identified as the causative agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome with mortality rates as high as 10% [12, 13, 14]. Subsequently, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1 were identified in 2004 and 2005, causing generally mild respiratory infections [15, 16, 17]. More recently, a novel zoonotic coronavirus, named Middle East respiratory syndrome CoV (MERS-CoV) was isolated from patients with a rapidly deteriorating acute respiratory illness [18•, 19]. According to a recent study describing the clinical manifestation of 144 laboratory-confirmed MERS-CoV cases, the majority of patients experience severe respiratory disease and most symptomatic cases had one or more underlying medical conditions [20]. Thus, the severity of CoV-associated disease in humans can apparently range from relatively mild (HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-HKU1) to severe (SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV). To further unravel the pathogenesis of these different CoVs, a deeper understanding of the CoV biology and interaction with their hosts is needed. In this review we focus on one of the very first interactions of CoVs with their hosts; the receptors required for cell entry.

Tissue distribution of coronavirus receptors

The ability of viruses to successfully replicate in cells and tissues of a host is multifactorial, of which receptor usage is an essential determinant. Enveloped coronaviruses engage host receptors via their spike (S) glycoprotein, the principle cell entry protein responsible for attachment and membrane fusion. In line with epidemiological data and clinical manifestations all human infecting CoVs are capable of infecting cells in respiratory tract. Remarkably, all protein receptors identified to date for these CoV are exopeptidases; aminopeptidase N (APN) for HCoV-229E, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) for SARS-CoV and HCoV-NL63, and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) for MERS-CoV [21••, 22••, 23, 24]. Protein receptors have not been identified for HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU1, rather, for HCoV-OC43 acetylated sialic acid has been proposed as a receptor for attachment [25].

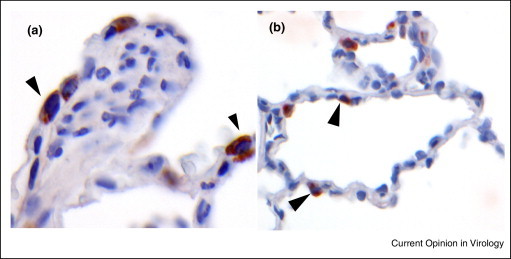

The respiratory and enteric tissue distribution of the peptidases makes them attractive targets for viruses to enter the host. APN is expressed at the basal membrane of the bronchial epithelium, in submucosal glands and the secretory epithelium of bronchial glands [26]. In addition, non-ciliated bronchial epithelial cells are positive for APN correlating with the ability of HCoV-229E to infect those cells [27]. ACE2 is expressed on type I and II pneumocytes, endothelial cells, and ciliated bronchial epithelial cells [28]. Tissues of the upper respiratory tract, such as oral and nasal mucosa and nasopharynx, did not show ACE2 expression on the surface of epithelial cells, suggesting that these tissues are not the primary site of entrance for SARS-CoV or HCoV-NL63 [28]. In the alveoli of the lower respiratory tract, infection of type I and II pneumocytes has been shown for SARS-CoV in vivo [29]. DPP4 is widely expressed in the human body and primarily localized to the epithelial and endothelial cells of virtually all organs, and on activated lymphocytes [30]. This distribution of DPP4 can potentially allow dissemination of MERS-CoV beyond the respiratory tract but due to lack of autopsy and clinical data, the in vivo organ and cell tropism of MERS CoV is largely unexplored. Experimental infection of rhesus macaques demonstrated that MERS-CoV particularly replicates in the type I and II pneumocytes of the alveoli and the draining lymphoid tissue of the lungs [31]. Detection of viral genomes and infectious virus in respiratory specimens indicate that the virus is primarily replicating in the upper and lower respiratory tract, although low viral RNA loads were also found in blood, urine and stool samples [32, 33]. Apart from propagation in continuous cell lines, the virus replicates in human primary cells isolated from the bronchus and kidney and in ex vivo bronchial and lung tissues cultures. Target cell types in the respiratory tract for MERS-CoV are known to express DPP4 and include the non-ciliated bronchiolar epithelial cells, endothelial cells and alveolar type I and II pneumocytes [34, 35] (Figure 1 ). Collectively, the correlation between cell susceptibility to HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV and the expression of the respective peptidase receptors, confirms that receptor expression is an essential determinant for virus tropism.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical detection of DPP4 expression in the lower respiratory tract of non-human primates. Lungs from naïve Cynomolgus macaques were inflated with formalin and subsequently processed for paraffin embedding. Sections were stained with goat polyclonal antibodies against human DPP4 and the second antibody step that was conjugated with peroxidase was visualized with substrate. Shown are positive cells in the bronchus (a) and alveoli (b).

Co-localization of cellular proteases with coronavirus receptors

Binding of CoVs to their receptors, however, does not suffice for viral infection and additional protease activities are needed to allow membrane fusion with the target cells. CoVs do not use the catalytic activity present in the membrane ectopeptidases that serve as receptor [21••, 22••]. Rather, cellular proteases that colocalize with CoV receptors are key factors for viral entry by activation of the spike fusion machinery [36, 37]. For example, TMPRSS2 found together with ACE2 on the cell surface cleaves the SARS-CoV spike protein and thus enhances virus entry [38]. Interestingly, despite using the same receptor, HCoV-NL63 and SARS-CoV display major differences in virus tropism and pathogenesis [1]. The protease responsible for HCoV-NL63 S cleavage has not been identified thus far, clearly indicating that tropism as well as severity of disease is governed by more viral and cellular parameters than receptor preference. Therefore, peptidase receptors and host protease(s) are targeted by CoVs to enter the host cell and their differential usage may partly determine the pathogenicity of CoVs.

Evolutionary conservation of coronavirus receptors

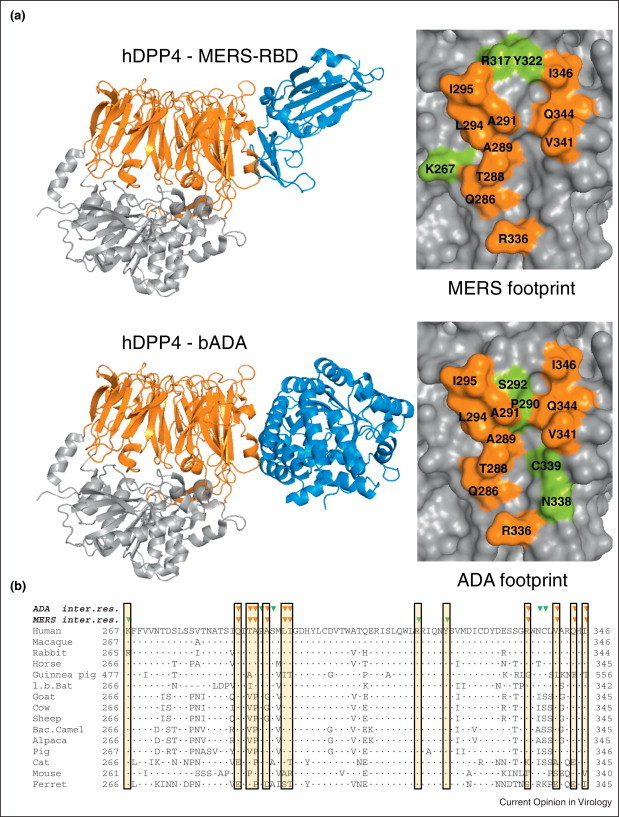

The ACE2, APN and DPP4 peptidases are highly conserved among animal species. This conservation is also present at the virus binding motif on these receptors, indicated by the ability of CoV — in particular MERS-CoV — to recruit ortholog receptors in vitro [39, 40]. The sequence variation at the virus-receptor interface is thought to be determined — at least in part — by the ongoing evolutionary battle between the genomes of viruses and their hosts also known as ‘host–virus arms race’ [41••]. Particularly known are the arms races between mammalian innate immunity genes and their viral counterparts, but these forces are also believed to occur at the level of virus-receptor binding. Positive selection for genetic changes in virus binding motifs on host receptor molecules which prevent virus binding has been shown for arenaviruses and retroviruses [41••]. Some pathogens target binding sites of natural ligands on the host receptors [42••], which may constrain the evolution potential of the host to counteract virus binding. The recently elucidated structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor binding domain in complex with human DPP4 shows a remarkable overlap with the binding surface of a natural ligand, adenosine deaminase (ADA) [43•, 44•, 45]. Ten out of 14 residues on DPP4 which interact with ADA also interact with MERS-CoV RBD (Figure 2 ). In accordance with this finding, it was shown that ADA prevents binding of S to DPP4 and antagonizes MERS-CoV infection in cell culture [21••, 46]. During species evolution, the ADA-DPP4 interaction may have led to conservation of residues at the binding interface, exemplified by the ability of bovine ADA to interact with human DPP4 [46]. The observed low level of variation in MERS-CoV-contacting residues between DPP4 orthologs — presumably constrained during divergent evolution by the DPP4-ADA interplay – explains the promiscuous binding of MERS-CoV to DPP4 orthologs and may facilitate virus transmission between species (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MERS-CoV and ADA binding sites on DPP4. (a) Cartoon representation of human DPP4 (hDPP4; β-propellor and hydrolase domain in orange respectively gray) in complex with — in blue — MERS-CoV receptor binding domain (MERS-RBD) or bovine adenosine deaminase (bADA). Left panels: Surface representation of the hDPP4 region with the footprints of ADA and MERS-CoV RBD. Contacting residues (based on Refs [43•, 44•]) are assigned in single-letter code and sequence number and colored orange for contacting residues commonly binding MERS-RBD and ADA, or in green for residues specifically contacting MERS-CoV or ADA. Figures were created using PyMol (www.pymol.org) (b) Amino acid sequence alignment of region of DPP4 binding ADA and MERS. Residues in the alignment identical to that of human DPP4 are indicated by a dot. Green triangles on top indicate amino acids in hDPP4 engaged in complex formation with MERS-CoV or ADA as indicated. Orange triangles indicate amino acids in hDPP4 engaged in complex formation with MERS and ADA. Boxed regions indicate the MERS-CoV-contacting residues of DPP4. DPP4 accession numbers: Homo sapiens ref|NP_001926.2|, Macaca mulatta ref|NP_001034279.1|, Oryctolagus cuniculus ref|XP_002712206.1|, Equus caballus ref|XP_005601601.1|, Cavia porcellus ref|XP_003478612.2|, Myotis lucifugus ref|XP_006083275.1|, Capra hircus ref|XP_005676104.1|, Bos Taurus ref|NP_776464.1|, Ovis aries ref|XP_004004709.1|, Camelus ferus ref|XP_006176871.1|, Vicugna pacos ref|XP_006196279.1|, Sus scrofa ref|NP_999422.1|, Felis catus ref|NP_001009838.1|, Mus musculus ref|XP_006498756.1|, Mustela putorius furo ref|XP_004744010.1|.

Pathogenic consequences of peptidase receptor recruitment by coronaviruses

The membrane ectopeptidases display important physiological functions and their interaction with CoVs may therefore interfere with their natural function. The human ACE2 protein, a typical zinc metallopeptidase, is an important player in the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), cardinal in renal and cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology [47]. Angiotensin II, the main effector substance of the RAAS, with potent vasoconstrictive, pro-inflammatory, and pro-fibrotic properties is inactivated by ACE2. As a result of diminished ACE2 expression severe acute lung failure may develop through hampering angiotensin II cleavage, causing pathological changes due to angiotensin II type 1a receptor activation [48]. Interestingly, binding of the SARS-CoV spike protein to ACE2 does trigger internalization, downregulating enzyme activity from the cell surface [49•]. Therefore, it is assumed that interaction of SARS-CoV with its receptor may cause detrimental pathogenic host responses partly responsible for the severe acute respiratory distress syndrome.

At the moment it is not clear whether similar virus–host interactions are involved in the pathogenesis of MERS-CoV. DPP4 is a multifunctional type II cell surface glycoprotein with an N-terminal beta-propellor domain and a C-terminal hydrolase domain that and can form dimers. Through interactions with specific proteins, DPP4 is involved in cell adhesion, cell apoptosis and lymphocyte stimulation (for review see [30]). Similar to ACE2, DPP4 exhibits dipeptidase activity, removing N-terminal dipeptides of regulatory hormones and chemokines, but it is not known whether MERS-CoV interferes with DPP4 expression. Soluble forms of DPP4 and ADA are found in the body fluid and sera of humans and hence can antagonize virus receptor binding and potentially interfere with virus dissemination. On the other hand, competition of MERS-CoV with ADA for binding to DPP4 may impair proper functioning of the DPP4-ADA complex. The association of ADA to DPP4 is thought to be important as a costimulatory signal to promote proliferation of lymphocytes and cytokine production [30]. Thus, although highly speculative, MERS-CoV binding to the ADA-binding site on DPP4-expressing immune cells may antagonize or exert the immune stimulatory functions of ADA. Intriguingly, other CoV receptors like APN and murine CEACAM are also markers for T-cell activation [50].

Conclusions and outlook

The preference of a significant number of human infecting CoV as well as animal CoV for peptidases as host receptors is remarkable. The respiratory and enteric tissue distribution of these ectopeptidases correlates with the sites of replication of coronaviruses, but does not fully explain this preference. The catalytic activity of the ACE2, APN, and DPP4 peptidases is not required for virus entry, yet interference of CoVs with the peptidase functions may partly drive viral pathogenesis. Evolutionary conservation of these receptors on the other hand may allow their usage in different host species, enabling zoonotic transmission. One may exploit the inhibitory activity of recombinant soluble receptors on CoV infection for therapeutic intervention strategies to interfere with CoV entry into target cells. However, more studies are needed to decipher the role of receptors in targeting CoVs to their target cells in vivo and the potential pathogenic consequences of the CoV-peptidase receptor interaction. In conclusion, the interaction of viral pathogens with host receptors and their role in pathogenesis remains a largely unexplored area and warrants future research.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mark Bakkers who assisted in preparing figures. Saskia L Smits is part time senior scientist of Viroclinics Biosciences B.V. This work was supported by a grant from the Dutch Scientific Research (NWO; no. 40-00812-98-13066) and NIAID/NIH contract HHSN266200700010C.

References

- 1.Weiss S.R., Navas-Martin S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:635–664. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.635-664.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vijgen L., Keyaerts E., Moes E., Thoelen I., Wollants E., Lemey P., Vandamme A.M., Van R.M. Complete genomic sequence of human coronavirus OC43: molecular clock analysis suggests a relatively recent zoonotic coronavirus transmission event. J Virol. 2005;79:1595–1604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1595-1604.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfefferle S., Oppong S., Drexler J.F., Gloza-Rausch F., Ipsen A., Seebens A., Muller M.A., Annan A., Vallo P., Adu-Sarkodie Y. Distant relatives of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and close relatives of human coronavirus 229E in bats, Ghana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1377–1384. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ithete N.L., Stoffberg S., Corman V.M., Cottontail V.M., Richards L.R., Schoeman M.C., Drosten C., Drexler J.F., Preiser W. Close relative of human Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bat, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1697–1699. doi: 10.3201/eid1910.130946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huynh J., Li S., Yount B., Smith A., Sturges L., Olsen J.C., Nagel J., Johnson J.B., Agnihothram S., Gates J.E. Evidence supporting a zoonotic origin of human coronavirus strain NL63. J Virol. 2012;86:12816–12825. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00906-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li W., Shi Z., Yu M., Ren W., Smith C., Epstein J.H., Wang H., Crameri G., Hu Z., Zhang H. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1118391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan Y., Zheng B.J., He Y.Q., Liu X.L., Zhuang Z.X., Cheung C.L., Luo S.W., Li P.H., Zhang L.J., Guan Y.J. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003;302:276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haagmans B.L., Al Dhahiry S.H., Reusken C.B., Raj V.S., Galiano M., Myers R., Godeke G.J., Jonges M., Farag E., Diab A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:140–145. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70690-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradburne A.F., Bynoe M.L., Tyrrell D.A. Effects of a “new” human respiratory virus in volunteers. Br Med J. 1967;3:767–769. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5568.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamre D., Procknow J.J. A new virus isolated from the human respiratory tract. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1966;121:190–193. doi: 10.3181/00379727-121-30734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McIntosh K., Dees J.H., Becker W.B., Kapikian A.Z., Chanock R.M. Recovery in tracheal organ cultures of novel viruses from patients with respiratory disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1967;57:933–940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.57.4.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drosten C., Gunther S., Preiser W., van der Werf S., Brodt H.R., Becker S., Rabenau H., Panning M., Kolesnikova L., Fouchier R.A. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ksiazek T.G., Erdman D., Goldsmith C.S., Zaki S.R., Peret T., Emery S., Tong S., Urbani C., Comer J.A., Lim W. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peiris J.S., Chu C.M., Cheng V.C., Chan K.S., Hung I.F., Poon L.L., Law K.I., Tang B.S., Hon T.Y., Chan C.S. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361:1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fouchier R.A., Hartwig N.G., Bestebroer T.M., Niemeyer B., de Jong J.C., Simon J.H., Osterhaus A.D. A previously undescribed coronavirus associated with respiratory disease in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6212–6216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400762101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Hoek L., Pyrc K., Jebbink M.F., Vermeulen-Oost W., Berkhout R.J., Wolthers K.C., Wertheim-van Dillen P.M., Kaandorp J., Spaargaren J., Berkhout B. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat Med. 2004;10:368–373. doi: 10.1038/nm1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Chu C.M., Chan K.H., Tsoi H.W., Huang Y., Wong B.H., Poon R.W., Cai J.J., Luk W.K. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J Virol. 2005;79:884–895. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.884-895.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18•.Zaki A.M., van B.S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First report on the identification of the novel emerging coronavirus that causes MERS.

- 19.van Boheemen S., de Graaf M., Lauber C., Bestebroer T.M., Raj V.S., Zaki A.M., Osterhaus A.D., Haagmans B.L., Gorbalenya A.E., Snijder E.J. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. MBio. 2012:3. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00473-12. pii:mBio.00473-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Who Mers-Cov Research Group State of knowledge and data gaps of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in humans. PLoS Curr. 2012:5. doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.0bf719e352e7478f8ad85fa30127ddb8. pii:ecurrents.outbreaks.0bf719e352e7478f8ad85fa30127ddb8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21••.Raj V.S., Mou H., Smits S.L., Dekkers D.H., Müller M.A., Dijkman R., Muth D., Demmers J.A., Zaki A., Fouchier R.A. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature. 2013;495:251–254. doi: 10.1038/nature12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Identification of the receptor that is used by MERS-CoV to infect cells.

- 22••.Li W., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S.K., Berne M.A., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J.L., Luzuriaga K., Greenough T.C. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Identification of the receptor that is used by SARS-CoV to infect cells.

- 23.Hofmann H., Pyrc K., van der Hoek L., Geier M., Berkhout B., Pöhlmann S. Human coronavirus NL63 employs the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor for cellular entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7988–7993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409465102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeager C.L., Ashmun R.A., Williams R.K., Cardellichio C.B., Shapiro L.H., Look A.T., Holmes K.V. Human aminopeptidase N is a receptor for human coronavirus 229E. Nature. 1992;357:420–422. doi: 10.1038/357420a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schultze B., Herrler G. Recognition of N-acetyl-9-O-acetylneuraminic acid by bovine coronavirus and hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1993;342:299–304. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2996-5_46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Velden V.H., Wierenga-Wolf A.F., Adriaansen-Soeting P.W., Overbeek S.E., Moller G.M., Hoogsteden H.C., Versnel M.A. Expression of aminopeptidase N and dipeptidyl peptidase IV in the healthy and asthmatic bronchus. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28:110–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dijkman R., Jebbink M.F., Koekkoek S.M., Deijs M., Jonsdottir H.R., Molenkamp R., Ieven M., Goossens H., Thiel V., van der Hoek L. Isolation and characterization of current human coronavirus strains in primary human epithelial cell cultures reveal differences in target cell tropism. J Virol. 2013;87:6081–6090. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03368-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamming I., Timens W., Bulthuis M.L., Lely A.T., Navis G., van G.H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye J., Zhang B., Xu J., Chang Q., McNutt M.A., Korteweg C., Gong E., Gu J. Molecular pathology in the lungs of severe acute respiratory syndrome patients. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:538–545. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambeir A.M., Durinx C., Scharpe S., De Meester I. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV from bench to bedside: an update on structural properties, functions, and clinical aspects of the enzyme DPP IV. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2003;40:209–294. doi: 10.1080/713609354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Wit E., Rasmussen A.L., Falzarano D., Bushmaker T., Feldmann F., Brining D.L., Fischer E.R., Martellaro C., Okumura A., Chang J. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) causes transient lower respiratory tract infection in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16598–16603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310744110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drosten C., Seilmaier M., Corman V.M., Hartmann W., Scheible G., Sack S., Guggemos W., Kallies R., Muth D., Junglen S. Clinical features and virological analysis of a case of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013:3–4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70154-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guery B., Poissy J., el Mansouf L., Séjourné C., Ettahar N., Lemaire X., Vuotto F., Goffard A., Behillil S., Enouf V. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet. 2013;381:2265–2272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kindler E., Jónsdóttir H.R., Muth D., Hamming O.J., Hartmann R., Rodriguez R., Geffers R., Fouchier R.A., Drosten C., Müller M.A. Efficient replication of the novel human betacoronavirus EMC on primary human epithelium highlights its zoonotic potential. MBio. 2013;4:e00611–e612. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00611-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan R.W., Chan M.C., Agnihothram S., Chan L.L., Kuok D.I., Fong J.H., Guan Y., Poon L.L., Baric R.S., Nicholls J.M. Tropism of and innate immune responses to the novel human betacoronavirus lineage C virus in human ex vivo respiratory organ cultures. J Virol. 2013;87:6604–6614. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00009-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heald-Sargent T., Gallagher T. Ready, set, fuse! The coronavirus spike protein and acquisition of fusion competence. Viruses. 2012;4:557–580. doi: 10.3390/v4040557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gierer S., Bertram S., Kaup F., Wrensch F., Heurich A., Krämer-Kühl A., Welsch K., Winkler M., Meyer B., Drosten C. The spike protein of the emerging betacoronavirus EMC uses a novel coronavirus receptor for entry, can be activated by TMPRSS2, and is targeted by neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2013;87:5502–5511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00128-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shulla A., Heald-Sargent T., Subramanya G., Zhao J., Perlman S., Gallagher T. A transmembrane serine protease is linked to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor and activates virus entry. J Virol. 2011;85:873–882. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02062-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tresnan D.B., Levis R., Holmes K.V. Feline aminopeptidase N serves as a receptor for feline, canine, porcine, and human coronaviruses in serogroup I. J Virol. 1996;70:8669–8674. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8669-8674.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eckerle I., Corman V.M., Müller M.A., Lenk M., Ulrich R.G., Drosten C. Replicative capacity of MERS coronavirus in livestock cell lines. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.3201/eid2002.131182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41••.Demogines A., Abraham J., Choe H., Farzan M., Sawyer S.L. Dual host–virus arms races shape an essential housekeeping protein. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors show that by constantly replacing the amino acids encoded at just a few residue positions, transferrin receptor divorces adaptation to ever-changing viruses from preservation of key cellular functions.

- 42••.Drayman N., Glick Y., Ben-nun-shaul O., Zer H., Zlotnick A., Gerber D., Schueler-Furman O., Oppenheim A. Pathogens use structural mimicry of native host ligands as a mechanism for host receptor engagement. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides evidence that both bacterial and viral pathogens have evolved to structurally mimic native host ligands thus enabling engagement of their cognate host receptors.

- 43•.Lu G., Hu Y., Wang Q., Qi J., Gao F., Li Y., Zhang Y., Zhang W., Yuan Y., Bao J. Molecular basis of binding between novel human coronavirus MERS-CoV and its receptor CD26. Nature. 2013;500:227–231. doi: 10.1038/nature12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Analysis of the crystal structures of both the free receptor binding domain (RBD) of the MERS-CoV spike protein and its complex with DPP4/CD26. The atomic details at the interface between the two binding entities reveal a surprising protein-protein contact mediated mainly by hydrophilic residues.

- 44•.Wang N., Shi X., Jiang L., Zhang S., Wang D., Tong P., Guo D., Fu L., Cui Y., Liu X. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res. 2013;23:986–993. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The crystal structure of MERS-CoV RBD bound to the extracellular domain of human DPP4 is provided. The atomic details at the interface between MERS-CoV RBD and DPP4 provide structural understanding of the virus and receptor interaction.

- 45.Weihofen W.A., Liu J., Reutter W., Saenger W., Fan H. Crystal structure of CD26/dipeptidyl-peptidase IV in complex with adenosine deaminase reveals a highly amphiphilic interface. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43330–43335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohnuma K., Haagmans B.L., Hatano R., Raj V.S., Mou H., Iwata S., Dang N.H., Bosch B.J., Morimoto C. Inhibition of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection by anti-CD26 monoclonal antibody. J Virol. 2013;87:13892–13899. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02448-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamming I., Cooper M.E., Haagmans B.L., Hooper N.M., Korstanje R., Osterhaus A.D., Timens W., Turner A.J., Navis G., van Goor H. The emerging role of ACE2 in physiology and disease. J Pathol. 2007;212:1–11. doi: 10.1002/path.2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imai Y., Kuba K., Rao S., Huan Y., Guo F., Guan B., Yang P., Sarao R., Wada T., Leong-Poi H., Crackower M.A., Fukamizu A., Hui C.C., Hein L., Uhlig S., Slutsky A.S., Jiang C., Penninger J.M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49•.Kuba K., Imai Y., Rao S., Gao H., Guo F., Guan B., Huan Y., Yang P., Zhang Y., Deng W. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study evidence is provided that SARS CoV infection and the Spike protein reduce ACE2 expression. In addition, injection of Spike protein into mice worsens acute lung failure in vivo that can be attenuated by blocking the renin–angiotensin pathway.

- 50.Nakajima A., Iijima H., Neurath M.F., Nagaishi T., Nieuwenhuis E.E. Activation-induced expression of carcinoembryonic antigen-cell adhesion molecule 1 regulates mouse T lymphocyte function. J Immunol. 2002;168:1028–1035. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]